Considerations for Conservative, All-Ceramic Prosthodontic Single-Tooth Replacements in the Anterior Region: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Systematic Search Strategy

- P (problem): single-tooth replacement; anterior teeth.

- I (intervention): resin-bonded fixed partial denture; cantilever fixed dental prosthesis.

- C (comparison): three-unit prosthesis; three-unit prosthesis; all-ceramic; lithium disilicate; monolithic; zirconia fixed dental prosthesis.

- O (outcome): survival [MeSH]; success.

2.3. Study Selection

- Studies in English.

- Treatment concepts with one-retainer all-ceramic RBFDPs and three-unit conventional all-ceramic FPDs in the anterior region.

- Clinical studies only.

- Studies with a mean follow-up of at least 1 year.

- Studies reporting on details and outcomes of selected treatments.

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.6. Effect Measures for Synthesis

- Survival Rates: the percentage of restorations that remained in situ without major complications during the observation period in both the RBFDP and three-unit FPD groups.

- Success Rates: the percentage of restorations that remained functional, with minimal complications (such as debonding, chipping, or fractures) during the observation period in both groups.

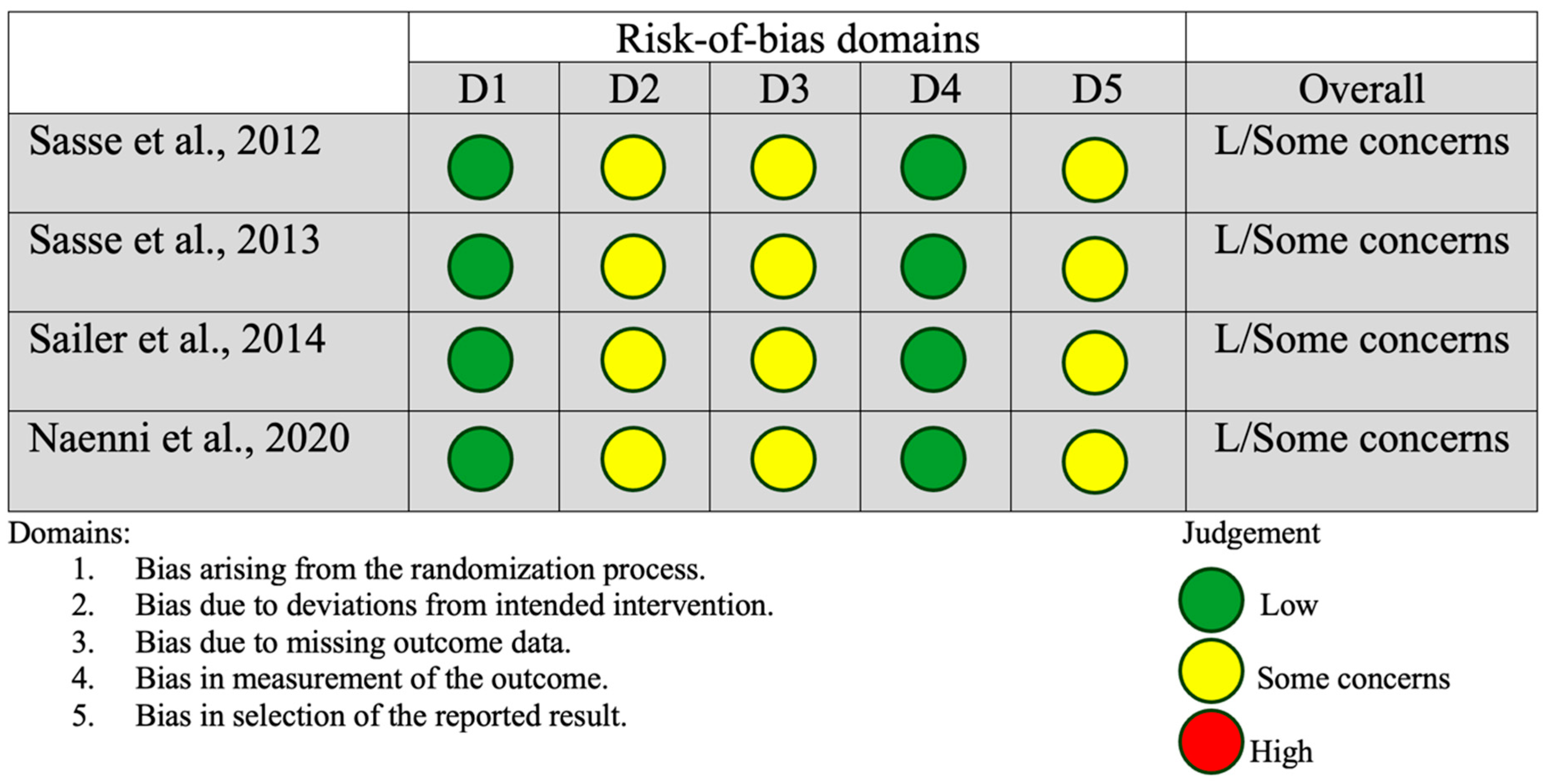

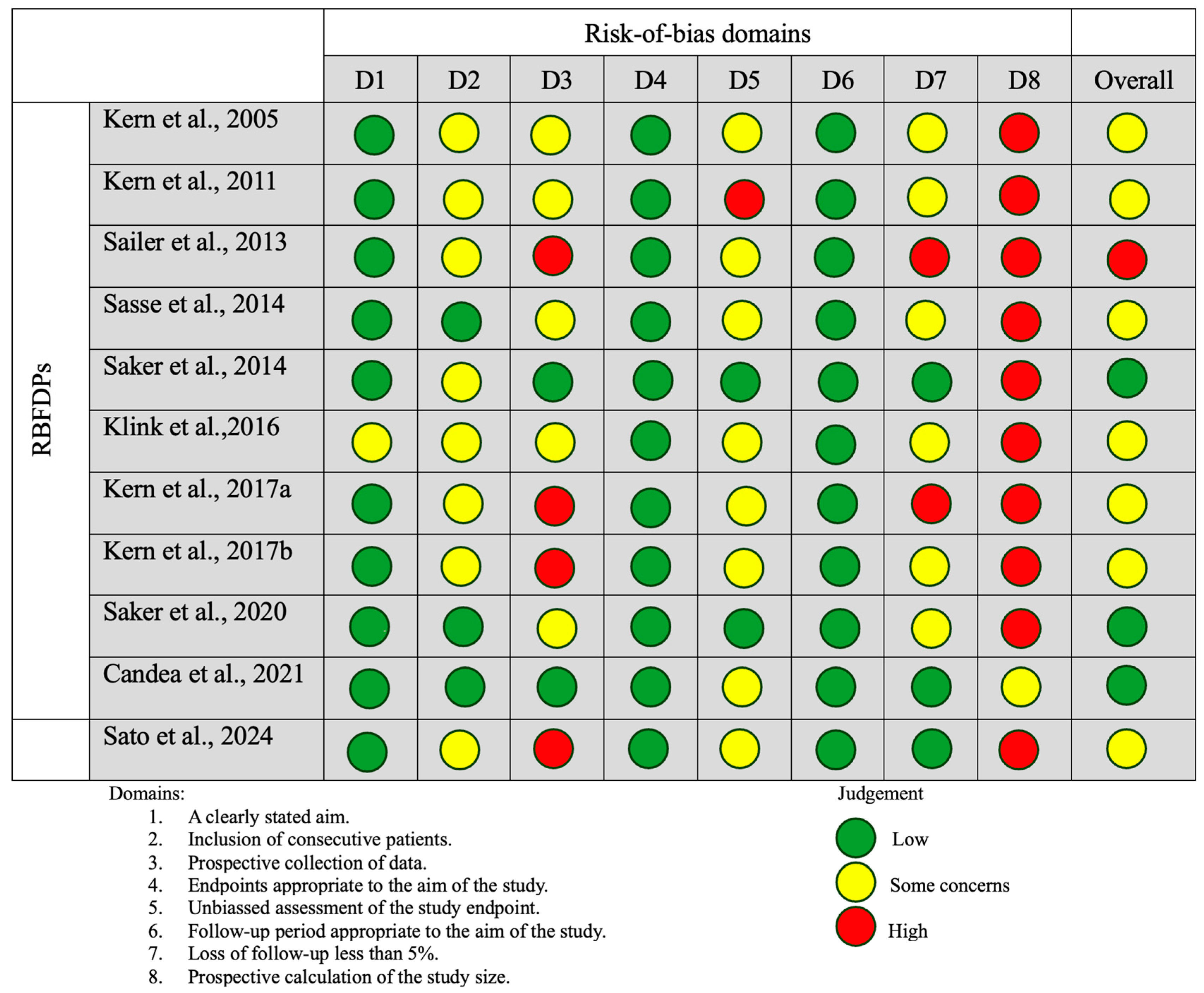

2.7. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

2.8. Data Synthesis

3. Results

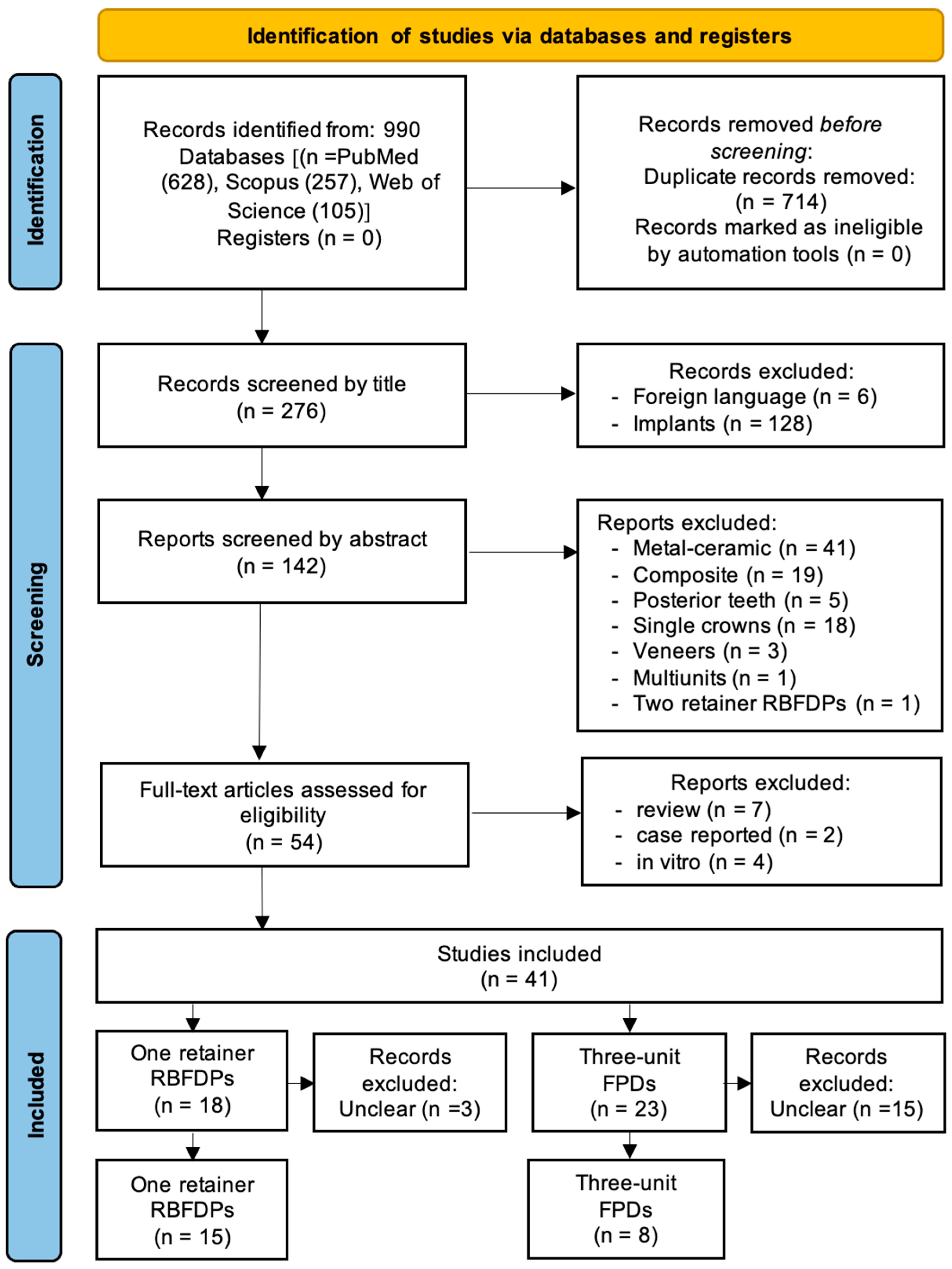

3.1. Included Studies

- Studies written in foreign languages (n = 6).

- Studies on implant-supported all-ceramic restorations (n = 128).

- Use of composite or metal–ceramic restorations (n = 60).

- Studies conducted on posterior teeth (n = 5).

- Studies employing different treatment concepts (n = 23) (Table 2).

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

3.3. RBFDPs

3.4. Three-Unit FPDs

3.5. Synthesis of Results

3.6. Reporting Bias

3.7. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rakhshan, V. Congenitally missing teeth (hypodontia): A review of the literature concerning the etiology, prevalence, risk factors, patterns and treatment. Dent. Res. J. 2015, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, A.H.; Antoun, J.S.; Thomson, W.M.; Merriman, T.R.; Farella, M. Hypodontia: An Update on Its Etiology, Classification, and Clinical Management. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9378325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekonja, A. Prevalence of dental developmental anomalies of permanent teeth in children and their influence on esthetics. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2017, 29, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petti, S.; Glendor, U.; Andersson, L. World traumatic dental injury prevalence and incidence, a meta-analysis-One billion living people have had traumatic dental injuries. Dent. Traumatol. 2018, 34, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, R. Epidemiology and outcomes of traumatic dental injuries: A review of the literature. Aust. Dent. J. 2016, 61 (Suppl. S1), 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysanthakopoulos, N.A. Reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Greece: A five-year follow-up study. Int. Dent. J. 2011, 61, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqain, Z.H.; Khraisat, A.; Sawair, F.; Ghanam, S.; Shaini, F.J.; Rajab, L.D. Dental extraction for patients presenting at oral surgery student clinic. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2007, 28, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kannaiyan, K.; Prasad, V.; Chander, V.B.; Avinash, R.; Kouser, A. Esthetic and Palliative Management of Congenitally Missing Anterior Teeth using All Ceramic Fixed Prosthesis: A Clinical Case Report. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13 (Suppl. S2), S1737–S1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldon, K.; Barber, S.K.; Spencer, R.J.; Duggal, M.S. Indications for the use of auto-transplantation of teeth in the child and adolescent. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2012, 13, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.P.; Rauniyar, S. Orthodontic Space Closure of a Missing Maxillary Lateral Incisor Followed by Canine Lateralization. Case Rep. Dent. 2020, 2020, 8820711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawa, A.; Seth-Johansen, C.; Jensen, S.S.; Gotfredsen, K. Resin-bonded fixed dental prosthesis versus implant-supported single crowns in the anterior region. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2023, 25, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebel, K.; Gajjar, R.; Hofstede, T. Single-tooth replacement: Bridge vs. implant-supported restoration. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2000, 66, 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Kullar, A.S.; Miller, C.S. Are There Contraindications for Placing Dental Implants? Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelhoff, D.; Sorensen, J.A. Tooth structure removal associated with various preparation designs for anterior teeth. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2002, 87, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaskar, P.S.; Sonkesriya, S.; Singh, R.; Palekar, U.; Bagde, H.; Dhopte, A. Evaluation and Comparison of Five-Year Survival of Tooth-Supported Porcelain Fused to Metal and All-Ceramic Multiple Unit Fixed Prostheses: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, M. Clinical long-term survival of two-retainer and single-retainer all-ceramic resin-bonded fixed partial dentures. Quintessence Int. 2005, 36, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, M.; Sasse, M. Ten-year survival of anterior all-ceramic resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses. J. Adhes. Dent. 2011, 13, 407–410. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, M.; Eschbach, S.; Kern, M. Randomized clinical trial on single retainer all-ceramic resin-bonded fixed partial dentures: Influence of the bonding system after up to 55 months. J. Dent. 2012, 40, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, M.; Kern, M. CAD/CAM single retainer zirconia-ceramic resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses: Clinical outcome after 5 years. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2013, 16, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sailer, I.; Bonani, T.; Brodbeck, U.; Hämmerle, C.H. Retrospective clinical study of single-retainer cantilever anterior and posterior glass-ceramic resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses at a mean follow-up of 6 years. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2013, 26, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailer, I.; Hämmerle, C.H. Zirconia ceramic single-retainer resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses (RBFDPs) after 4 years of clinical service: A retrospective clinical and volumetric study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2014, 34, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, M.; Kern, M. Survival of anterior cantilevered all-ceramic resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses made from zirconia ceramic. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saker, S.; El-Fallal, A.; Abo-Madina, M.; Ghazy, M.; Ozcan, M. Clinical survival of anterior metal-ceramic and all-ceramic cantilever resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses over a period of 60 months. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 7, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klink, A.; Hüttig, F. Zirconia-Based Anterior Resin-Bonded Single-Retainer Cantilever Fixed Dental Prostheses: A 15- to 61-Month Follow-Up. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 29, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.; Passia, N.; Sasse, M.; Yazigi, C. Ten-year outcome of zirconia ceramic cantilever resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses and the influence of the reasons for missing incisors. J. Dent. 2017, 65, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, M. Fifteen-year survival of anterior all-ceramic cantilever resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses. J. Dent. 2017, 56, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naenni, N.; Michelotti, G.; Lee, W.Z.; Sailer, I.; Hämmerle, C.H.; Thoma, D.S. Resin-Bonded Fixed Dental Prostheses with Zirconia Ceramic Single Retainers Show High Survival Rates and Minimal Tissue Changes After a Mean of 10 Years of Service. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 33, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saker, S.; Ghazy, M.; Abo-Madina, M.; El-Falal, A.; Al-Zordk, W. Ten-Year Clinical Survival of Anterior Cantilever Resin-Bonded Fixed Dental Prostheses: A Retrospective Study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 33, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cândea, A.; Goguţă, L.M.; Frandes, M.; Jivanescu, A. Zirconia Minimally Invasive Partial Retainer Fixed Dental Prostheses: Up to Ten Year Follow-Up. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 34, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Hosaka, K.; Tagami, J.; Tashiro, H.; Miki, H.; Otani, K.; Nishimura, M.; Takahashi, M.; Shimada, Y.; Ikeda, M. Clinical evaluation of direct composite versus zirconia resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses for a single missing anterior tooth: A short-term multicenter retrospective study. J. Dent. 2024, 151, 105401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pröbster, L. Survival rate of In-Ceram restorations. Int. J. Prosthodont. 1993, 6, 259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, S.E. A report of anterior In-Ceram restorations. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 1995, 24, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfart, S.; Bohlsen, F.; Wegner, S.M.; Kern, M. A preliminary prospective evaluation of all-ceramic crown-retained and inlay-retained fixed partial dentures. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2005, 18, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Taskonak, B.; Sertgöz, A. Two-year clinical evaluation of lithia-disilicate-based all-ceramic crowns and fixed partial dentures. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.; Sasse, M.; Wolfart, S. Ten-year outcome of three-unit fixed dental prostheses made from monolithic lithium disilicate ceramic. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2012, 143, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solá-Ruíz, M.F.; Agustin-Panadero, R.; Fons-Font, A.; Labaig-Rueda, C. A prospective evaluation of zirconia anterior partial fixed dental prostheses: Clinical results after seven years. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 113, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadhli, R.; Alshammari, Y.; Baig, M.R.; Omar, R. Clinical outcomes of single crown and 3-unit bi-layered zirconia-based fixed dental prostheses: An upto 6- year retrospective clinical study: Clinical outcomes of zirconia FDPs. J. Dent. 2022, 127, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homa, M.; Schneider, O.; Neumann, P.; Endres, L.; Rafai, N.; Reich, S.; Wolfart, S.; Tuna, T. Three-unit CAD/CAM-manufactured lithium disilicate FDPs after an average observation period of 120 months. J. Dent. 2025, 155, 105625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurisic, S.; Rath, A.; Gaber, S.; Garattini, S.; Bertele, V.; Ngwabyt, S.N.; Hivert, V.; Neugebauer, E.A.M.; Laville, M.; Hiesmayr, M.; et al. Barriers to the conduct of randomised clinical trials within all disease areas. Trials 2017, 18, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriter, M.; Huband, N. Does the non-randomized controlled study have a place in the systematic review? A pilot study. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2005, 15, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezulas, E.; Yildiz, C.; Evren, B.; Ozkan, Y. Clinical procedures, designs, and survival rates of all-ceramic resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses in the anterior region: A systematic review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarone, F.; Di Mauro, M.I.; Ausiello, P.; Ruggiero, G.; Sorrentino, R. Current status on lithium disilicate and zirconia: A narrative review. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P.; Brito, P.; Pereira, J.; Alves, R. The importance of the optical properties in dental silica-based ceramics. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2012, 40, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guazzato, M.; Albakry, M.; Swain, M.V.; Ironside, J. Mechanical properties of In-Ceram Alumina and In-Ceram Zirconia. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2002, 15, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Edelhoff, D.; Liebermann, A.; Beuer, F.; Stimmelmayr, M.; Güth, J.F. Minimally invasive treatment options in fixed prosthodontics. Quintessence Int. 2016, 47, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ghodsi, S.; Jafarian, Z. A Review on Translucent Zirconia. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2018, 26, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gotfredsen, K.; Alyass, N.S.; Hagen, M.M. A 5-year, randomized clinical trial on 3-unit fiber-reinforced versus 3- or 2-unit, metal-ceramic, resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 34, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, M.G.; Chan, A.W.; Leung, N.C.; Lam, W.Y. Long-term evaluation of cantilevered versus fixed-fixed resin-bonded fixed partial dentures for missing maxillary incisors. J. Dent. 2016, 45, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- King, P.A.; Foster, L.V.; Yates, R.J.; Newcombe, R.G.; Garrett, M.J. Survival characteristics of 771 resin-retained bridges provided at a UK dental teaching hospital. Br. Dent. J. 2015, 218, 423–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraheam, I.A.; Ngoc, C.N.; Wiesen, C.A.; Donovan, T.E. Five-year success rate of resin-bonded fixed partial dentures: A systematic review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2019, 31, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buso, L.; Oliveira-Júnior, O.B.; Hiroshi Fujiy, F.; Leão Lombardo, G.H.; Ramalho Sarmento, H.; Campos, F.; Assunção Souza, R.O. Biaxial flexural strength of CAD/CAM ceramics. Minerva Stomatol. 2011, 60, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.M.; Smale, R.J.; Yip, K.H.; Sung, W.J. Translucency and biaxial flexural strength of four ceramic core materials. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 1506–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Strategy | |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE via PubMed (advanced research) | Title/Abstract single tooth replacement [Title/Abstract] OR anterior teeth cantilever fixed dental prosthesis [Title/Abstract] OR resin bonded fixed partial denture [Title/Abstract] OR three-unit prosthesis [Title/Abstract] OR 3-unit prosthesis [Title/Abstract] OR all-ceramic [Title/Abstract] OR lithium disilicate [Title/Abstract] OR monolithic [Title/Abstract] OR zirconia fixed dental prosthesis [Title/Abstract]) AND (survival [Title/Abstract] [MeSH] OR success [Title/Abstract]) |

| Scopus (advanced search) | Title-Abstract-Keywords single AND tooth AND Replacement OR anterior AND teeth AND cantilever AND fixed AND dental AND prosthesis OR resin AND bonded AND fixed AND partial AND denture OR three-unit AND prosthesis OR 3-unit AND prosthesis OR all-ceramic OR lithium AND disilicate OR monolithic OR zirconia AND fixed AND dental AND prosthesis AND survival OR success |

| Web of Science (advanced research) | Keywords (AK = (single tooth replacement OR anterior teeth cantilever fixed dental prosthesis OR resin bonded fixed partial denture OR three-unit prosthesis OR 3-unit prosthesis OR all-ceramic OR lithium disilicate OR monolithic OR zirconia fixed dental prosthesis)) AND AK = (success OR survival) |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Human trials | Animal trials, in vitro studies, preclinical trials |

| Studies in English | Studies in foreign languages |

| Study design: clinical studies (RCTs, PCS, RCSs, CCTs) | Study design: case reports, case series, systematic reviews |

| Studies with a mean follow-up of at least 1 year | Studies with a mean follow-up of less than 1 year |

| Studies reporting on details and outcomes of selected treatments | Studies employing different treatment concepts |

|

|

|

| Author | Type of Study | No of Restorations | Material | Technique | Mean Observation Time | Survival Rate | Success Rate/Failure Rate | Modes of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kern et al. [16] 2005 | PCS | 21 | In-Ceram alumina, zirconia/Vitadur-Alpha | copy milling/veneered | mean 51 ± 17 months | 92.3% | 1 fracture | |

| Kern et al. [17] 2011 | PCS | 22 | In-Ceram alumina, zirconia/Vitadur-Alpha | copy milling/veneered | mean 111 ± 44 months | 94.4% | 1 fracture | |

| Sasse et al. [21] 2012 | RCT | 30 | IPS e.max ZirCAD/IPS e.max Ceram | milled/veneered | mean 41.7 months | 100% at 3 y 93.1% at 3 y | 2 debondings 1 rotation | |

| Sasse et al. [22] 2013 | RCT | 30 | IPS e.max ZirCAD/IPS e.max Ceram | milled/veneered | mean 64.2 months | 100% | failure free rate 93.3% | 2 debondings 1 rotation secondary caries |

| Sailer et al. [23] 2013 | RCS | 20 | IPS e.max Press and IPS Empress/IPS e.max Ceram | pressed/ veneered | 60 months | 100% | chipping rate 5% | 1 chipping |

| Sailer et al. [24] 2014 | RCT | 15 | IPS e.max ZirCAD/GC Initial | milled/veneered | mean 53.3 ± 23 months | 100% at 4 y | 2 debondings | |

| Sasse et al. [25] 2014 | PCS | 39 | zirconia/IPS e.max Ceram | milled/veneered | mean 61.6 months | 100% 6 y | failure-free rate 94.8% after 6 y success rate 97.4% after 6 y | 1 debonding secondary caries |

| Saker et al. [26] 2014 | CCT | 20 | In-Ceram alumina/ | not reported | mean 34 months | 90% after 5 y | annual failure rate 0.05% | 2 fractures 3 debondings |

| Klink et al. [27] 2016 | PCS | 23 | zirconia (diff) | milled/veneered | mean 35 ± 15 months | 100% at 36 m | success rate 82.4% at 36 m | 2 chippings 1 debonding 1 tooth movement |

| Kern et al. [28] 2017 | RCS | 108 | zirconia | milled/ veneered | mean 92.2 ± 33 months | 100% | success rate 92% after 10 y | 6 debondings 1 lost restoration |

| Kern et al. [29] 2017 | PCS | 22 | In-Ceram alumina, zirconia/ Vitradur-Alpha | copy milling/veneered | mean 188.7 ± 47.6 months | 95.4% after 10 y 95.4% after 15 y 81.8% after 18 y | 2 framework fractures | |

| Naenni et al. [30] 2020 | RCT | 10 | IPS e.max ZirCAD/Initial | milled/veneered | mean 11 y | 100% after 10 y | 2 debondings | |

| Saker et al. [31] 2020 | RCS | 20 | In-Ceram alumina/VM7 | slip casting/ veneered | mean 106.7 ± 24.4 months | 85% after 10 y | clinical retention rate 70% after 10 y | 3 fractures 6 debondings |

| Candea et al. [32] 2021 | PCS | 18 (position not defined) | Zenotec/Zirox Lava Plus/IPS e.max Ceram | milled/ veneered | mean 5.11 ± 1.18 y | 100% both anterior and posterior | ||

| Sato et al. [33] 2024 | RCS | 28 | zirconia (unspecified) | unspecified | 3 y | 91.7% | 1 debonding |

| Author | Type of Study | No of Restorations | Material | Technique | Observation Time | Survival Rate | Failure Rate/Success Rate | Modes of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probster et al. [34] 1993 | PCS | 5 | In-Ceram alumina Vitradur-Alpha | slip casting/veneered | mean 16.3 months | 100% | ||

| Pang et al. [35] 1995 | PCS | 3 | In-Ceram alumina/Vitadur-Alpha | slip casting/ veneered | 21 months | 100% | localised mild gingivitis (position not clear) | |

| Wolfart et al. [36] 2005 | PCS | 6 | IPS e.max Press | pressed monolithic | mean 48 months | 100% | ||

| Taskonak et al. [37] 2006 | PCS | 12 | Empress 2 | pressed | 24 months | satisfactory rate 50% | 2 chippings 4 fractures | |

| Kern et al. [38] 2012 | PCS | 6 | IPS e.max Press | pressed monolithic | 60 months | 100% | ||

| Sola-Ruiz et al. [39] 2015 | PCS | 10 | Lava/Lava Ceram | milled/veneered | 84 months | 90% | 1 removal (secondary caries) | |

| Alfadhli et al. [40] 2022 | RCS | 8 | KaVo Everest ZS/IPS e.max Ceram | milled/veneered | mean 25 months | 87.5% | 1 framework fracture | |

| Homa et al. [41] 2025 | PCS | 16 | IPS e.max CAD LT | milled/ veneered | 10 y | 81.3% | 87.5% | 1 framework facture 2 removals (pain) 1 chipping |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knezović Zlatarić, D.; Soldo, M. Considerations for Conservative, All-Ceramic Prosthodontic Single-Tooth Replacements in the Anterior Region: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13050219

Knezović Zlatarić D, Soldo M. Considerations for Conservative, All-Ceramic Prosthodontic Single-Tooth Replacements in the Anterior Region: A Systematic Review. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(5):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13050219

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnezović Zlatarić, Dubravka, and Mirko Soldo. 2025. "Considerations for Conservative, All-Ceramic Prosthodontic Single-Tooth Replacements in the Anterior Region: A Systematic Review" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 5: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13050219

APA StyleKnezović Zlatarić, D., & Soldo, M. (2025). Considerations for Conservative, All-Ceramic Prosthodontic Single-Tooth Replacements in the Anterior Region: A Systematic Review. Dentistry Journal, 13(5), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13050219