Abstract

Background/Objective: To outline strategies for the safe clinical use of orthodontic temporary anchorage devices (TADs) by analyzing papers that examine associated risks, complications, and approaches for their prevention and resolution. Methods: The research protocol used PubMed, Medline, and Scopus up to May 2024, focusing on controlled and randomized clinical trials aligned with the review objective. Fourteen studies were included; bias risk was assessed, key data extracted, and a descriptive analysis performed. Study quality and evidence strength were also evaluated. Results: TADs optimize anchorage control without relying on patient compliance. However, they carry risks and complications. TAD contact with the periodontal ligament or root without pulp involvement requires removal for spontaneous healing. If pulp is involved, the TAD should be removed and endodontic therapy performed. If anatomical structures are violated, TAD should be removed. If transient, spontaneous recovery occurs, but sometimes pharmacological treatment may be needed. A 2 mm gap between the TAD and surrounding structures can prevent damage. In the maxillary sinus, a less than 2 mm perforation of the Schneiderian membrane recovers spontaneously; wider perforations require TAD removal. Good oral hygiene and TAD abutments prevent soft tissue inflammation, which resolves with 0.2% chlorhexidine for 14 days. Unwanted forces can cause TAD fractures, requiring removal. Minor TAD mobility due to loss of primary stability can be maintained; significant instability requires repositioning. Conclusions: The use of TADs requires meticulous planning, radiological guidance, and monitoring to minimize risks and manage complications. With proper care, TADs improve orthodontic outcomes and patient satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Temporary anchorage devices (TADs), particularly miniscrews, have revolutionized orthodontics by providing reliable skeletal anchorage without relying on patient compliance. TADs are fixed to bone to support or eliminate reactive units and are removed after use [1]. They address the critical challenge of anchorage control, enabling controlled tooth movement and reducing the limitations of traditional methods [2,3,4,5].

The development of miniscrews was inspired by the need for maximum anchorage with minimal patient cooperation [2,3,6]. In 1983, Creekmore and Eklund demonstrated that small screws could withstand orthodontic forces [7,8,9]. Later innovations, such as Kanomi’s orthodontic mini-implant (1997) and Costa’s bracket-like miniscrew (1998), made TADs smaller, simpler to insert and remove, and capable of immediate loading [7].

Compared to traditional implants, miniscrews are minimally invasive, do not require osteointegration, have immediate load-bearing capability, and can be placed in constrained anatomical areas due to their smaller size and smoother surfaces [2,3,5,10]. They are versatile and can be used in various procedures such as space closure, molar uprighting, open bite correction, correction of canted occlusal planes and dental midline alignment, molar distalization or mesialization, anterior retraction, and teeth extrusion or intrusion [2,7,10,11,12]. Miniscrews are especially useful in cases in which conventional anchorage techniques are impractical such as in edentulous spaces, the palate, the zygomatic process, or the retromolar region [13].

Despite their benefits, miniscrews have some limitations. Contraindications include compromised systemic health, poor oral hygiene, pathological bone quality, and smoking [2,12]. TADs failure can arise from factors such as root or periodontal ligament contact, inadequate insertion torque, soft tissue inflammation, and anatomical complications such as sinus perforation or nerve injury [2,12,13,14]. The mandible shows higher failure rates due to increased bone density and insertion torque requirement [2].

Proper screw design and insertion technique have a key role to ensure treatment success. Screws may be self-tapping or self-drilling, with cylindrical or conical shafts and diameters ranging from 1 to 2 mm [2,7,14]. Thinner screws reduce the risk of root contact but are more prone to fracture, especially in areas of high bone density [2,7]. The choice of insertion site influences screw design; for example, thicker cortical bone may necessitate shorter screws, while thinner bone requires longer devices to achieve stability [2,7]. Other anatomical factors related to the insertion technique should also be contemplated. In the maxilla, miniscrews should be inserted obliquely at a 30–40° angle, while, in the mandible, a parallel or slightly oblique (10–20°) insertion is recommended [12,13]. Pilot drilling may be required for cortical bone exceeding 2 mm in thickness, ensuring miniscrew stability and reducing insertion resistance [7]. The self-tapping method is the most common insertion technique, requiring pilot drilling to ensure precision and mechanical stability. Pilot holes should be 0.2–0.5 mm thinner than the implant diameter [15,16]. The newer self-drilling method simplifies placement by eliminating the need for pilot drilling [17,18]. In cases without digital support, TADs are placed perpendicular to the bone surface behind the third palatal rugae, using clinical landmarks for guidance. Polyether impressions ensure accuracy and dimensional stability. Casts are made with plaster, replicating TAD positions for orthodontic device fabrication [19,20,21,22].

The digital workflow involves CBCT imaging and a superimposed dental scanning of the patient palate and upper arch. Miniscrews are selected from a virtual library and placed based on bone availability and the intended device. Placement typically occurs in the anterior paramedian area, between the second and third palatal rugae, 4–5 mm from the midline, ensuring parallelism and avoiding tooth roots [20,21,22,23]. The surgical guide is digitally designed with guiding holes, prototyped, and finalized. During the procedure, local anesthesia is applied, and a drill with a calibrated stop is used to create pilot holes in the palatal cortical bone. After miniscrew placement, scan bodies are captured in a digital impression, and the orthodontic device is fitted as the final step [24,25]. Miniscrews have proven to be a versatile and reliable tool for anchorage in orthodontics. However, their success depends on careful planning, proper insertion techniques, and effective management of complications. Maintaining good oral hygiene is crucial to minimize soft tissue inflammation and the risk of screw loosening [12,26].

This review aims to investigate the complications and risks associated with orthodontic miniscrews and outline strategies for their prevention and management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focused Questions

What are the clinical and surgical complications related to orthodontic miniscrews?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review were (I) study design—interventional studies and observational studies; (II) patients undergoing miniscrew placement; (III) interventions—miniscrew placement; and (IV) outcome—clinical and mechanical complications of TADs. The analysis focused solely on studies that met all the inclusion criteria. Studies were excluded if they met any of the following conditions: (I) abstracts published in languages other than English; (II) duplicate publications; (III) studies unrelated to the specific research questions, such as those examining different supplementary treatments or not matching the abstract content; (IV) ex vivo or animal experimental studies; (V) studies lacking ethics committee approval; (VI) narrative, systematic, or meta-analytical review articles; and (VII) case reports lacking sufficient scientific validity compatible with the requirements of our work.

2.3. Search Strategy

A three-step search procedure was conducted based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews. First, an initial limited search was performed using PubMed (MEDLINE) and Scopus. Next, key terms were gathered from the retrieved articles to develop a comprehensive search strategy. Lastly, the reference lists of all selected articles were reviewed to find any other relevant studies [27].

Additionally, the population–concept–context (PCC) framework was utilized. PCC is based on three key elements: the population (people who experience complications from TADs insertion), the concept (complications related to TADs placement), and the context (not limited to any particular cultural or environmental setting). This review involved careful examination of study abstracts focused on various complications related to TADs placement. Throughout the process, adherence was maintained to the Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines, as outlined in Table S1 [28].

2.4. Research

The terms used for Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) included “orthodontic anchorage procedures”, “dental im-plant”, “intraoperative complications”, “root resorption” “cicatrix”, and “mouth mucosa”. Research was conducted in the PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, and Web of Science databases.

Articles published from 2004 to 2025 were included, and data was collected between February 2024 and May 2025.

The search was carried out by two reviewers (M.G. and C.D.R.). Any disagreements that arose during the review process were settled through mutual agreement among the reviewers. An additional reviewer (P.P.P.) was consulted for complex cases. The first step of screening consisted of reviewing article titles and abstracts to eliminate those that were not relevant. Afterward, the selected articles were examined in detail by thoroughly reading their full texts. The results were documented, and studies that met the established inclusion criteria and showed similarities were included in this review. This protocol has been registered on the Open Science Framework platform (Registration DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/QSKXF, accessed on 21 June 2025).

The specific search strategies used for each electronic database are detailed in Table S2.

2.5. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

The possibility of bias in clinical studies was assessed in this research by using a qualitative method based on the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Quality Assessment tool for Controlled Intervention Studies applicable to Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. This approach provided a detailed and organized evaluation of the quality and bias risks in the studies included, aiming to confirm the reliability and validity of their findings [29].

3. Results

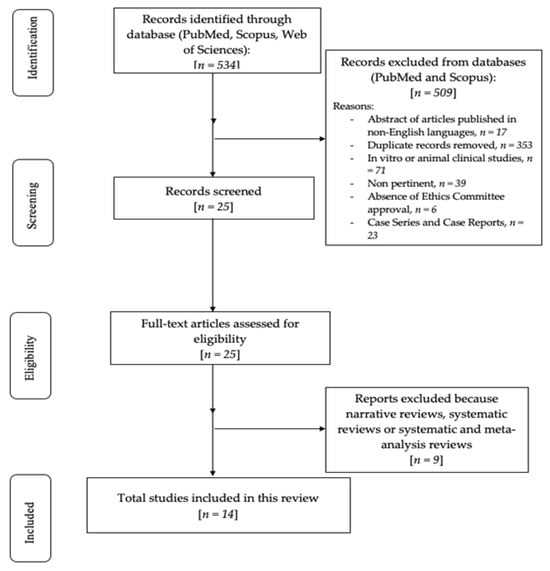

The preliminary search selected 534 articles relying on MeSH terms. After this, 509 articles were eliminated (17 abstracts of articles published in non-English languages, 353 duplicates, 71 in vitro or animal clinical studies, 39 were not pertinent, in 6 the Ethics Committee approval was not provided, and 23 were case reports and case series). A total of 25 articles were analyzed according to title and abstracts. Nine articles were excluded because impertinent, while the remaining fourteen were assessed for eligibility, included, and screened in this review. The review process is summarized in the flowchart shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the review process.

Table S3 (Supplementary Materials) presents the studies that were excluded from this review along with the reasons for their exclusion [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. The included studies were divided into two categories: controlled intervention studies [3,4,41,42,43,44,45] and observational cohort studies [46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Risk of Bias

The articles selected for this review were assessed for risk of bias using the ROBINS-I tool, as detailed in Table 1. The evaluation was carried out following the criteria outlined in the ROBINS-I assessment tool shown in Table S4 (Supplementary Materials). Table S5 details the bias risk of the studies included in this review as evaluated by the ROBINS-I tool. This review found a moderate risk of bias across the included studies.

Table 1.

Rrisk of bias in the included studies, with green symbols indicating low risk and yellow indicating high risk.

Table 2 shows patient’s baseline data from the selected studies. Table S6 (Supplementary Materials) summarizes study details, including design, methods, results, and conclusions.

Table 2.

Patient baseline data from the selected studies.

Table S7 (Supplementary Materials) presents the NHLBI Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.

4. Discussion

Anchorage has been a significant issue in orthodontics since the advent of permanent appliances and has garnered significant attention. Orthodontics has made use of a number of these extra-dental anchor types, including the traditional osteo-integrated implants, mini plates [53,54,55] and, more recently, mini-implants. The benefits of mini-implants are their great adaptability, ease of surgical implantation, and inexpensive cost [56,57,58]. The success rate for implant anchorage ranges between 85 and 95% [59,60,61] according to the literature; however, complications will inevitably develop despite its simplicity, in part due to the relatively inexperienced clinicians executing it. The aforementioned complications can be further subdivided into four categories: surgical complications, which occur during TADs placement, orthodontics complications, which occur after its mechanical loading, soft tissue issues, and removal complications [62].

4.1. Surgical Complications

Periodontal Ligament Injury, Root Contact with or Without Pulpal Involvement

Orthodontic miniscrews placed interradicularly run the danger of injuring the dental root or the periodontal ligament. Osteosclerosis, dentoalveolar ankylosis, and tooth vitality loss are possible side effects of root damage [63]. The prognosis of the tooth will probably not be affected by trauma to the external dental root if there is no pulpal involvement. After the orthodontic miniscrew is removed, the periodontium and the dental roots injured by the device are shown to fully heal in 12 to 18 weeks [64,65,66]. Appropriate radiological planning, which includes a surgical guide with panoramic and periapical radiographs, is required to determine the safest location for interradicular miniscrew placement. The maxillary buccal region’s thickest interradicular bone is located 5 to 8 mm from the alveolar crest, in the space between the second premolar and the first molar. The maximum amount of interradicular bone in the mandibular buccal region is located approximately 11 mm from the alveolar crest, either between the first and second molars or between the second premolar and the first molar [67,68,69]. It is common for the clinician to unintentionally draw the hand-driver toward their body during interradicular implantation in the posterior region, changing the angle of insertion and raising the possibility of root contact. The physician may be thinking about using a finger wrench or moving the hand-driver slightly away from the body with every motion to prevent this. With topical anesthetic, the patient will feel more sensation if the miniscrew starts to near the periodontal ligament. The miniscrew may halt or start to demand more insertion force if root contact is made. The physician should undo the miniscrew two or three turns and do a radiographic examination if trauma is suspected [70,71,72]. Another variable to consider as concerns root proximity is horizontal and vertical inclination. It has been shown that, in frontal view, vertical inclinations usually are approximately 50 degrees in the upper jaw and 60 degrees in the lower jaw. Mini-implants placed in the maxilla tend to be inserted at a more slanted angle compared to those in the mandible. This difference may result from the different perspectives when placing miniscrews in a reclining patient; in the maxilla, the drill’s direction is more visible when slanted, while, in the mandible, the drilling direction is observed from above along the dental arch. This difference in view influences the insertion angle of the miniscrews between the two jaws [43]. As concerns horizontal inclination in the axial view, the implant in the left mandible was placed nearly perpendicular to the bone surface, whereas implants in the left maxilla and right mandible were angled more distally. This variation is influenced by the sitting patient’s viewpoint, with drilling direction in the left mandible being easier to observe. Angling the implant opposite to the direction of the applied traction force may provide stronger anchorage due to increased stability [43]. As concerns dental pulp necrosis it has been shown that, among patients who exhibited a negative reaction to cold testing, TADS were often placed at the second rugae. It is reasonable to infer that inserting them more posteriorly towards the third rugae would better maintain vitality. In the anterior maxilla, proper insertion of the TAD is crucial to prevent damage to the incisor roots. Perpendicular insertion should be avoided and vertical placement to the bone surface is preferred to ensure the safety of this area [48,62]. Clinicians can place miniscrews either vertically or at an angle, as no insertion angle has been proven superior. The choice should depend on patient-specific factors such as anatomy, tooth and root position, and the type of force applied. This decision does not impact the clinical survival of miniscrews [3].

The results of vitality testing are, perhaps unsurprisingly, inconclusive. Vitality testing in cases of trauma is notoriously unreliable and this would seem to be borne out in this study [46]. The literature shows that proximity between the miniscrew and the root has moderate correlation for miniscrews’ failure [4].

4.2. Miniscrew Slipping

Miniscrew insertion with high forces can lead to its slippage. This can occur when the miniscew is inserted with a decreased insertion angle lower than 30° with respect to the occlusal plane. This complication can be prevented by starting the insertion at an obtuse angle to the occlusal plane and then reducing it to two to three turns while tightening the screw in and by applying light forces [61,72].

4.3. Nervous Damage

Another surgical complication that can occur is sensitive alteration, such as hypoesthesia. This could be due to indirect damage: nerve compression or direct nerve involvement. Specifically, an interesting area for this problem is the anterior maxilla. The course of the nasopalatine canal is still debated to date. The anatomical topography of the area has been already explored regarding fixture placement, and the same goes for TADs placement [64,73].

4.4. Subcutaneous Emphysema

It is a condition that can occur during different dental practices. It is most common during dental extraction or while using high-speed, air-driven surgical drills and compressed air syringes. In this instance, miniscrew placement can cause subcutaneous emphysema, which is air insufflation into the skin or submucosa that causes swelling. Only a few cases have been reported in the literature. The treatment consists of the RICE protocol application (Table 3) and a strict follow-up up to 10 days [74,75,76].

Table 3.

RICE protocol.

4.5. Sinus Perforation

During TADs placement several cases of sinus perforation have been documented. This can occur when the floor of the maxillary sinus is thin. However, sinus perforation does not necessarily lead to mini-implant failure or sinusitis. When the maxillary sinus floor thickness is less than 6.0 mm, the risk of sinus perforation with 8 mm miniscrews is significantly higher, with an odds ratio of 21.63 (p < 0.001) compared to cases where the thickness is 6.0 mm or more. Therefore, it is recommended to have at least 6.0 mm of sinus floor thickness to minimize the chance of maxillary sinus perforation during miniscrew insertion [65]. Penetration depth of the mini-implant causes changes in the sinus tissue conformation. Indeed, a thickening of 0.6 mm of the sinus membrane happens. A significantly higher value was observed around miniscrews that penetrated the sinus by more than 1 mm compared to those with less than 1 mm penetration (p < 0.017). This indicates that deeper penetration into the sinus is associated with greater effects than shallow penetration [50].

4.6. Bone Overheating

As concerns bone stress during TADs removal, a special note has to be made regarding temperature. The peak without irrigation can reach up to 50.9 degrees at 3 mm depth, while drilling with saline solution irrigation can decrease the heating to 37.4 degrees at 12 mm [64,77].

4.7. Orthodontic Complications: Failure of the Static Anchoring, Miniscrew Relocation

In the literature, there are only a few articles that discuss these variables. However, lateral forces on miniscrews may be unfavorable, but this needs more investigation. Minor deviations from the recommended insertion angle likely do not cause significant problems, making the technique suitable for less experienced practitioners, especially when deviations are necessary due to impacted teeth or clefts [50].

Orthodontic miniscrews can withstand forces effectively if there is sufficient bone support after a healing period. Clinically, loading is often delayed until around 3 months post-insertion, similar to traditional dental implants, as postponing the loading time reduces the risk of failure [45].

Both bone density and peri-implant soft tissue play a key role. Greater bone density reduces stress at the bone–screw interface and thin and keratinized mucosa, like the mid-palatal area, and stationary anchorage [22,78].

Under orthodontic loading, orthodontic miniscrews can stay rather stable, although not perfectly stationary. Orthodontic miniscrews achieve stability mainly through mechanical retention and can be shifted within the bone, while dental implants osteointegrate. Some cases have shown miniscrews tilting and extrusion of −1.0 to 1.5 mm when loaded with 400 g of force for 9 months. To accommodate this potential movement, clinicians are advised to maintain a safety margin of at least 2 mm between the miniscrew and any nearby anatomical structures to allow miniscrew migration [79].

4.8. Mechanical Complications

Miniscrew torsional stress, fracture, and bending: Excessive torsional forces can bend, fracture the miniscrew, or fracture the peri-implant bone, increasing the mobility of the screw [61,62,72]. These complications can be avoided either by using pilot drills in dense cortical [61,72] or by turning the screw two or three turns to reduce stress between screw and bone [72] and by removing the surrounding bone [60]. In case of screw fracture, it must be removed. If the TAD is subgingival, it is removed by making an incision; otherwise, no incision is needed to remove it if the TAD is supragingival [62].

4.9. Soft Tissue Complications

Scarring

Compared to insertion sites in the mucogingival junction or connected gingiva, TADs in the alveolar mucosa exhibited less scar development among the miniscrew-related parameters. According to histology, the alveolar mucosa is made up of far more elastic fibers than collagen, vascularized loose connective tissue, and nonkeratinized epithelium. These histological characteristics may help promote better wound healing. Maxillary buccal insertion sites have a higher likelihood of noticeable scarring than mandibular insertion sites. Miniscrews are more frequently placed in the attached gingiva of the maxilla than in the mandible because the attached gingiva in the maxillary buccal region is wider. Additionally, the flat gingival biotype typical of the maxillary buccal interdental area tends to be more susceptible to scarring [49].

Moreover, mini-screws placed between the second and third maxillary molars showed a significantly higher incidence than those placed between the first and second molars or between the first molar and second premolar [44].

Alternatively, the notable variations in scarring in the maxilla and mandible could have resulted from the disparities in bone composition between these two locations. Modifications in the food debris content, which are purportedly more common in the maxilla extraction sockets, could potentially impede the healing process following miniscrew extraction [49,80,81].

4.10. Aphthous Ulcerations

Small aphthous ulcerations can develop on the buccal mucosa next to the miniscrew head or around the miniscrew shaft. Minor aphthous ulcers are mainly caused by trauma to the soft tissues but can also result from bacterial infections, allergic reactions, hormonal changes, vitamin deficiencies, and genetic predispositions. Aphthae are defined as mildly painful ulcers that affect non-keratinized mucosa; these ulcers are self-limiting and heal without leaving scars in 7 to 10 days [82]. It is generally possible to prevent ulceration and improve patient comfort by using a wax pellet, a healing abutment, or a big elastic separator over the head of the miniscrew and by using chlorhexidine every day. Although it does not seem to be a direct risk factor for miniscrew stability, the development of an aphthous ulceration may indicate increased soft tissue inflammation [72].

4.11. Soft Tissue Overgrowth

When miniscrews are placed into the alveolar mucosa, especially in the jaw, soft tissue may conceal them. Within a day following placement, the head of the miniscrew and its attachments (like coil springs or elastic chains) may become covered by loose gum tissue that bunches up and rubs against them. This soft tissue growth can worry patients, who might think the miniscrew has fallen out, and it can also pose a risk to the stability of the miniscrew [83]. Tissue will probably cover any miniscrew attachments (coil springs and elastic chain) that are in contact with tissues. Light finger pressure can reveal the relatively thin, soft tissue covering the miniscrew, usually without the need for a cut or local anesthesia. The application of an elastic separator or healing abutment can reduce the amount of soft tissue overgrowth. Apart from its antibacterial characteristics, chlorhexidine also slows down the process of epithelization and can decrease the growth of soft tissues [84]. Overgrowth, defined as soft tissue partially or fully covering the miniscrew head, typically does not cause serious issues but can be a time-consuming nuisance. It may be prevented by reducing insertion depth or using implants with longer necks, with the latter preferred for ensuring better primary and long-term stability. Maintaining good oral hygiene is also important to avoid complications [52].

4.12. Peri-Implant Disease

Another complication that can affect TADs is peri-implant disease. Periodontal disease’s pathogenic mechanism results from bacteria and the chemicals they generate in plaque. Bacterial antigens and their toxic substances, such as toxins and enzymes, can damage periodontal tissues and provoke an immune response from the host. Peri-implanititis and periodontitis are similar in pathogenic microorganisms; however, peri-implanititis has a wider spectrum of bacteria and a stronger correlation with the red and orange complex [85]. From a microbiological point of view, failed TADs showed higher presence of microorganisms linked to periodontal disease, including Prevotella nigrescenis, Filifactor alocis, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum [86]. The literature suggests that the prevalence of inflammation (10.2%) between the palatal region and buccal fold can be overlapped. Peri-implant flogosis can be treated with an iodine-containing solution and chlorhexidine gel [47]. At longer follow-up times, up to 10 years after placement, the anterior alveolar region of the maxilla presented chronic inflammation mostly due to miniscrew placement in that area [51].

4.13. Removal Complication

Bone Damage

During TADs explantation, a phenomenon that can be experienced is bone sequester that can be addressed to undiagnosed diseases related to bone metabolism or smoking. Indeed, during the explantation procedure, excessive forces can lead to bone compression, thus necrosis, or insufficient irrigation [64].

In some cases, TADs can undergo partial osteointegration thanks to mechanical retention, thus leading to hard removal. The miniscrew usually can be extracted some days after the first attempt of removal [66].

Table 4 shows a summary of TAD’s complication incidence on the basis of the included articles for this review.

Table 4.

Summary of TADs complication incidence.

5. Conclusions

- -

- Miniscrews offer flexible and cost-effective orthodontic anchorage, yet their use requires careful planning and execution to avoid complications.

- -

- Surgical precision, guided by radiological assessment, is crucial to prevent periodontal ligament injury and root contact.

- -

- While orthodontic and mechanical issues can arise, diligent monitoring and post-placement care can mitigate these risks.

- -

- Soft tissue complications, such as scarring and ulcerations, underscore the importance of meticulous patient management. Similarly, the risk of peri-implant disease and bone damage during removal highlights the need for thorough assessment and intervention.

- -

- Despite challenges, advancements continue to improve miniscrew anchorage efficacy. With proper planning and ongoing monitoring, miniscrews can significantly enhance orthodontic outcomes, ensuring patient satisfaction and treatment success.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/dj13120582/s1, Table S1: PRISMA-ScR checklist; Table S2: Search strategies for electronic databases; Table S3: Summary table of studies excluded in this systematic review; Table S4: Criteria to assess bias risk using the ROBINS-I tool; Table S5: Risk of bias of the included studies through ROBINS-I assessment tool; Table S6: Evidence of the included studies; Table S7: NHLBI Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.P. and A.C.; methodology, P.P.P. and A.C.; software, C.d.R. and M.G.; validation, P.P.P. and A.C.; formal analysis, P.P.P. and A.C.; investigation, P.P.P. and A.C.; resources, P.P.P. and A.C.; data curation, C.d.R. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and C.d.R.; writing—review and editing, C.d.R. and M.G.; visualization, P.P.P. and A.C.; supervision, P.P.P. and A.C.; project administration, P.P.P. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Health—current research Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Sciences, University of Milan, Via della Commenda 10, 20122 Milan, Italy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cope, J.B. Temporary anchorage devices in orthodontics: A paradigm shift. Semin. Orthod. 2005, 11, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-P.; Tseng, Y.-C. Miniscrew implant applications in contemporary orthodontics. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2014, 30, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshah, A.; Gorji, K.; Nikkerdar, N. Effect on miniscrew insertion angle in the maxillary buccal plate on its clinical survival: A randomized clinical trial. Progress. Orthod. 2021, 22, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboshady, H.; Abouelezz, A.M.A.; Fotouh, M.H.A.; Elkordy, S.A.M. Failure Rate of Orthodontic Mini-screw After Insertion Using 3D Printed Guide Versus Conventional Free Hand Placement Technique: Split Mouth Randomized Clinical Trial. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.W.; Park, Y.-S.; Faot, F. Revisiting the Complications of Orthodontic Miniscrew. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8720421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motoyoshi, M.; Matsuoka, M.; Shimizu, N. Application of orthodontic mini-implants in adolescents. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 36, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melsen, B. Mini-implants: Where are we? J. Clin. Orthod. 2005, 9, 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Carano, A.; Velo, S.; Leone, P.; Siciliani, G. Clinical Applications of the Miniscrew Anchorage System. J. Clin. Orthod. 2005, 39, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, Y.C.; Hsieh, C.H.; Chen, C.H.; Shen, Y.S.; Huang, I.Y.; Chen, C.M. The application of mini-implants for orthodontic anchorage. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfondrini, M.F.; Gandini, P.; Alcozer, R.; Vallittu, P.K.; Scribante, A. Failure load and stress analysis of orthodontic miniscrews with different transmucosal collar diameter. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 87, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Lee, S.K.; Kwon, O.W. Group distal movement of teeth using microscrew implant anchorage. Angle Orthod. 2005, 75, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyoshi, M.; Yoshida, T.; Ono, A.; Shimizu, N. Effect of cortical bone thickness and implant placement torque on stability of orthodontic mini-implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2007, 22, 779–784. [Google Scholar]

- Morea, C.; Dominguez, G.; Wuo, A.; Tortamano, A. Surgical guide for optimal positioning of mini-implants. J. Clin. Orthod. 2005, 39, 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Florvaag, B.; Kneuertz, P.; Lazar, F.; Koebke, J.; Zöller, J.E.; Braumann, B.; Mischkowski, R.A. Biomechanical Properties of Orthodontic Miniscrews. An In-vitro Study. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2010, 71, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyoshi, M.; Hirabayashi, M.; Uemura, M.; Shimizu, N. Recommended placement torque when tightening an orthodontic mini-implant. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2006, 17, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, D.; Meyer, U.; Buchter, A. Success rate of mini- and micro-implants used for orthodontic anchorage: A prospective clinical study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2007, 18, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, U.; Ehmer, A.; Diedrich, P. Clinical suitability of titanium microscrews for orthodontic anchorage—Preliminary experiences. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2004, 65, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, C.; Zeng, X.; Wang, X. Microscrew anchorage in skeletal anterior open-bite treatment. Angle Orthod. 2007, 77, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iodice, G.; Nanda, R.; Drago, S.; Repetto, L.; Tonoli, G.; Silvestrini-Biavati, A.; Migliorati, M. Accuracy of direct insertion of TADs in the anterior palate with respect to a 3D-assisted digital insertion virtual planning. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2022, 25, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, J.T.; Cha, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Yu, H.S.; Hwang, C.J. Accuracy of miniscrew surgical guides assessed from cone-beam computed tomography and digital models. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 143, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Haruyama, N.; Suzuki, S.; Yamada, D.; Obayashi, N.; Kurabayashi, T.; Moriyama, K. Accuracy of orthodontic miniscrew implantation guided by stereolithographic surgical stent based on cone-beam CT–derived 3D images. Angle Orthod. 2012, 82, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Park, J.H.; Bay, R.C.; Choi, S.K.; Chae, J.M. Cortical bone thickness and bone density effects on miniscrew success rates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod. Craniofac Res. 2021, 24, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, B.; Glasl, B.; Bowman, S.J.; Wilmes, B.; Kinzinger, G.S.; Lisson, J.A. Anatomical guidelines for miniscrew insertion: Palatal sites. J. Clin. Orthod. 2011, 45, 433–441. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzan, L.; Migliorati, M.; Dinelli, L.; Riatti, R.; Torelli, L.; Di Lenarda, R.; Contardo, L. Accuracy of the digital workflow for guided insertion of orthodontic palatal TADs: A step-by-step 3D analysis. Prog. Orthod. 2022, 23, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagmode, S.; Kolte, R.P.; Aphale, H.; Shinde, V.; Kalaskar, V.; Ingle, V. CAD—CAM based 3D printed surgical guides for posterior mini-screw placement. Bioinformation 2025, 21, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, M.S.; Ulutas, P.A.; Ozenci, I.; Akcalı, A. Clinical and radiographic assessment of the association between orthodontic mini-screws and periodontal health. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tool. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Giudice, A.L.; Rustico, L.; Longo, M.; Oteri, G.; Papadopoulos, M.A.; Nucera, R. Complications reported with the use of orthodontic mini-screws: A systematic review. Korean J. Orthod. 2021, 51, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, S.N.; Zogakis, I.P.; Papadopoulos, M.A. Failure rates and associated risk factors of orthodontic miniscrew implants: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2012, 142, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Yang, Y.; Yaosen, C.; Badawy, R.; Alaa, M.; Maher, A. Effect of Operator-Related Factors on Failure Rate of Orthodontic Mini-Implants (OMIS) used as Temporary Anchorage Devices (TAD); Systematic Review. J. Dent. Oral Care Med. 2018, 4, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; Costa, S.; Fatone, M.C.; Avantario, P.; Campanelli, M.; Piras, F.; Patano, A.; Ferrara, I.; Di Pede, C.; et al. Tooth Complications After Orthodontic Miniscrews Insertion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Ossa, D.M.; Escobar-Correa, N.; Ramírez-Bustamante, M.A.; Agudelo-Suárez, A.A. An Umbrella Review of the Ef-fectiveness of Temporary Anchorage Devices and the Factors That Contribute to Their Success or Failure. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2020, 20, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakali, L.; Alharbi, M.; Pandis, N.; Gkantidis, N.; Kloukos, D. Success of palatal implants or mini-screws placed median or paramedian for the reinforcement of anchorage during orthodontic treatment: A systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. 2019, 41, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Ge, M.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z. Comparison of the success rate between self-drilling and self-tapping mini-screws: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2017, 39, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, W.K.; Chua, H.D.; Cheung, L.K. Bone anchor systems for orthodontic application: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 41, 1427–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, M.M.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Sultan, K.; Almahdi, W.H.; Alhaffar, J.B. Evaluation of the Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) with Temporary Skeletal Anchorage Devices in Fixed Orthodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlef, H.N.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Ajaj, M.A.; Heshmeh, O. Evaluation of Treatment Outcomes of En masse Retraction with Temporary Skeletal Anchorage Devices in Comparison with Two-step Retraction with Conventional Anchorage in Patients with Dentoalveolar Protrusion: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2018, 9, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gintautaitė, G.; Gaidytė, A. Surgery-related factors affecting the stability of orthodontic mini-implants screwed in alveolar process interdental spaces: A systematic literature review. Stomatologija 2017, 19, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fah, R.; Schatzle, M. Complications and adverse patient reactions associated with the surgical insertion and removal of palatal implants: A retrospective study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2014, 25, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyoshi, M.; Sanuki-Suzuki, R.; Uchida, Y.; Saiki, A.; Shimizu, N. Maxillary sinus perforation by orthodontic anchor screws. J. Oral Sci. 2015, 57, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, A.; Motoyoshi, M.; Uchida, Y.; Shimizu, N. Root proximity and inclination of orthodontic mini-implants after placement: Cone-beam computed tomography evaluation. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 144, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z. Buccal mucosal lesions caused by the inter radicular mini-screw: A preliminary report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2010, 25, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, L. Miniscrews for orthodontic anchorage: Analysis of risk factors correlated with the progressive susceptibility to failure. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbroni, G.; Aabed, S.; Mizen, K.; Starr, D.G. Transalveolar screws and the incidence of dental damage: A prospective study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 33, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdan, Z.; Szalma, J. Evaluation of the success and complication rates of self-drilling orthodontic mini-implants. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 546–552. [Google Scholar]

- Hourfar, J.; Bister, D.; Lisson, J.A.; Ludwig, B. Incidence of pulp sensibility loss of anterior teeth after paramedian insertion of orthodontic mini-implants in the anterior maxilla. Head Face Med. 2017, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.A.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, D.W.; Kim, K.H.; Chung, C.J. Cross-sectional evaluation of the prevalence and factors associated with soft tissue scarring after the removal of miniscrews. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, X. Influence of orthodontic mini-implant penetration of the maxillary sinus in the infra zygomatic crest region. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaki, T.; Tamura, N.; Yamamoto, M.; Takano, N.; Shibahara, T.; Yasumura, T.; Nishii, Y.; Sueishi, K. Clinical study of tem-porary anchorage devices for orthodontic treatment--stability of micro/mini-screws and mini-plates: Experience with 455 cases. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2010, 51, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebura, T.; Flieger, S.; Wiechmann, D. Mini-implants in the palatal slope—A retrospective analysis of implant survival and tissue reaction. Head Face Med. 2012, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turley, P.K.; Kean, C.; Schur, J.; Stefanac, J.; Gray, J.; Hennes, J. Orthodontic force application to titanium endosseous implants. Angle Orthod. 1988, 58, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roberts, W.E.; Helm, F.R.; Marshall, K.J.; Gongloff, R.K. Rigidendosseous implants for orthodontic and orthopedic anchorage. Angle Orthod. 1989, 59, 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Block, M.S.; Hoffman, D.R. A new device for absolute anchorage for orthodontics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1995, 107, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Raffaini, M.; Melsen, B. Miniscrews as orthodontic anchorage: A preliminary report. Int. J. Adult Orthod. Orthognath. Surg. 1998, 13, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthaler, J.W.; Haas, R.; Bantleon, H.P. Bicortical titanium screws for critical orthodontic anchorage in the mandible: A preliminary report on clinical application. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2001, 12, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umemori, M.; Sugawara, J.; Mitani, H.; Nagasaka, H.; Kawamura, H. Skeletal anchorage system for open-bite correction. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1999, 115, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, M.A.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Zogakis, I.P. Clinical effectiveness of orthodontic miniscrew implants: A meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Chang, H.H.; Lin, H.Y.; Lai, E.H.H.; Hung, H.C.; Yao, C.C.J. Stability of miniplates and miniscrews used for orthodontic anchorage: Experience with 492 temporary anchorage devices. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2008, 19, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.T.; Chen, M.H. Factors affecting the clinical success of orthodontic anchorage: Experience with 266 temporary anchorage devices. J. Dent. Sci. 2014, 9, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncone, C.E. Complications Encountered in Temporary Orthodontic Anchorage Device Therapy. Semin. Orthod. 2011, 17, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourfar, J.; Ludwig, B.; Bister, D.; Braun, A.; Kanavakis, G. The most distal palatal ruga for placement of orthodontic mini-implants. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asscherickx, K.; Vannet, B.V.; Wehrbein, H.; Sabzevar, M.M. Root repair after injury from miniscrew. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mine, K.; Kanno, Z.; Muramato, T.; Soma, K. Occlusal forces promote periodontal healing of transplanted teeth and prevent dentoalveolar ankylosis: An experimental study in rats. Angle Orthod. 2005, 75, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melsen, B.; Verna, C. Miniscrew implants: The Aarhus anchorage system. Semin. Orthod. 2005, 11, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carano, A.; Velo, S.; Incorvati, C.; Poggio, P. Clinical applications of the mini-screw anchorage system (M.A.S.) in the maxillary alveolar bone. Prog. Orthod. 2004, 5, 212–235. [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle, M.A.; Beck, F.M.; Jaynes, R.M.; Huja, S.S. A radiographic evaluation of the availability of bone for placement of mini screws. Angle Orthod. 2004, 74, 832–837. [Google Scholar]

- Poggio, P.M.; Incorvati, C.; Velo, S.; Carano, A. “Safe zones”: A guide for miniscrew positioning in the maxillary and mandibu lar arch. Angle Orthod. 2006, 76, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, E.Y.; Buranastidporn, B. An adjustable surgical guide for miniscrew placement. J. Clin. Orthod. 2005, 39, 588–590. [Google Scholar]

- Kyung, H.M.; Park, H.S.; Bae, S.M.; Sung, J.H.; Kim, I.B. Development of orthodontic micro-implants for intraoral anchorage. J. Clin. Orthod. 2003, 37, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz, N.D.; Kusnoto, B. Risks and complications of orthodontic miniscrews. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 131, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.M.; Balsiger, R.; Sendi, P.; von Arx, T. Morphology of the nasopalatine canal and dental implant surgery: A radiographic analysis of 100 consecutive patients using limited cone-beam computed tomography. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2011, 22, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgay, A.; Ayhin, E.; Cilasun, U.; Durmaz, L.; Arslan, G. Subcutane- ous emphysema after dental treatment: A case report. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2006, 16, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.H.; Yoon, S.; Chung, S.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, K.H.; Huh, J.K. Subcutaneous emphysema related to dental procedures. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 44, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman, N.J.; Owens, B.M.; Shelton, J.T. Subcutaneous emphysema after restorative dental treatment. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2001, 22, 38–40,42. [Google Scholar]

- Sener, B.C.; Dergin, G.; Gursoy, B.; Kelesoglu, E.; Slih, I. Effects of irrigation temperature on heat control in vitro at different drilling depths. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Yun, H.-S.; Park, H.-D.; Kim, D.-H.; Park, Y.-C. Soft-tissue and cortical-bone thickness at orthodontic implant sites. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 130, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, E.J.; Pai, B.C.; Lin, J.C. Do miniscrews remain stationary under orthodontic forces? Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2004, 126, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrokovski, J.; Massler, M. Ridge remodeling after tooth extraction in rats. J. Dent. Res. 1967, 46, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Chang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.P.; Chen, Y.J.; Chen, Y.J.; Lai, H.-H.E.; Yao, C.-C.J. Tissue reaction surrounding miniscrews for orthodontic anchorage: An animal experiment. J. Dent. Sci. 2012, 7, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.N.; McGuinness, N.; Biagioni, P.; Hyland, P.; Lamey, P.J. A comparative study of the efficacy of Aphtheal in the management of recurrent minor aphthous ulceration. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2005, 34, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, R.; Cope, J. Miniscrew implants: IMTEC mini ortho implants. Semin. Orthod. 2005, 11, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, S.; Haugen, E.; Gjermo, P. The effect of chlorhexidine supplementation in a periodontal dressing. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1989, 47, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafaurie, G.I.; Sabogal, M.A.; Castillo, D.M.; Rincón, M.V.; Gómez, L.A.; Lesmes, Y.A.; Chambrone, L. Microbiome and Microbial Biofilm Profiles of Peri-Implantitis: A Systematic Review. J. Periodontol. 2017, 88, 1066–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Cui, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X. Oral microbiome contributes to the failure of orthodontic temporary anchorage devices (TADs). BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).