Methacrylic Photopolymerizable Resin Incorporating Selenium Nanoparticles as a Basis for Additive Manufacturing of Functional Materials with Unique Biological Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Se NPs Colloid and Production of Se NPs-MR

4.2. Additive Manufacturing from Modified Resins

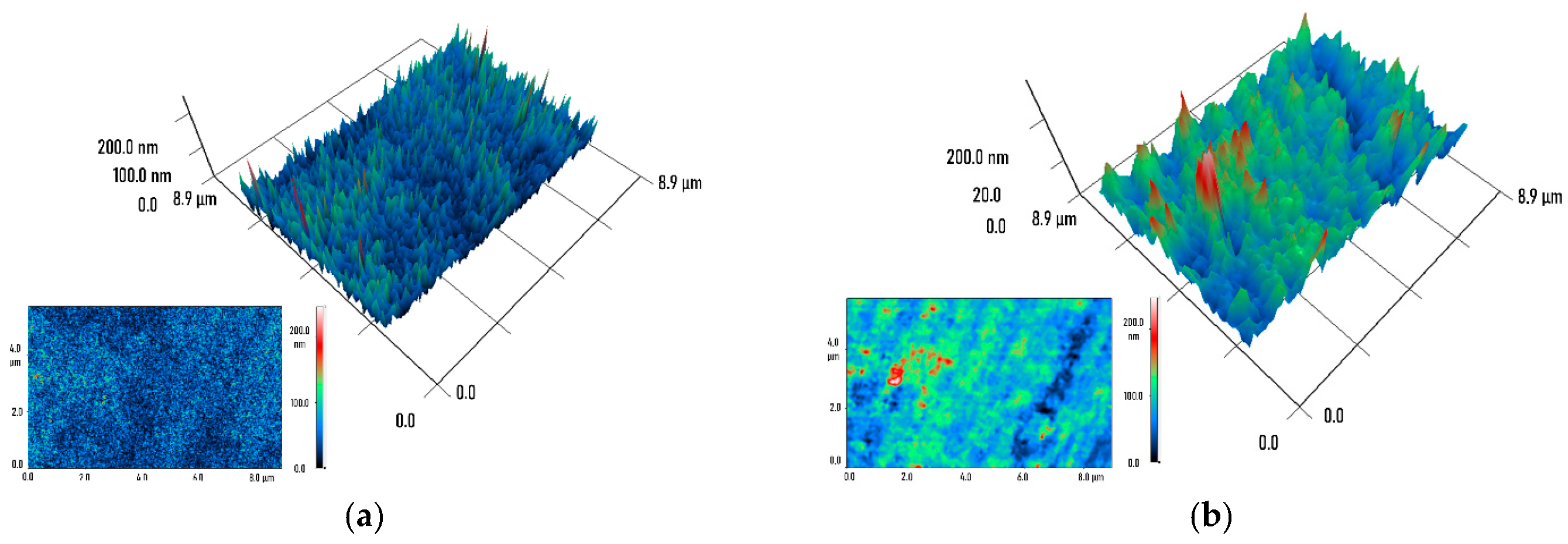

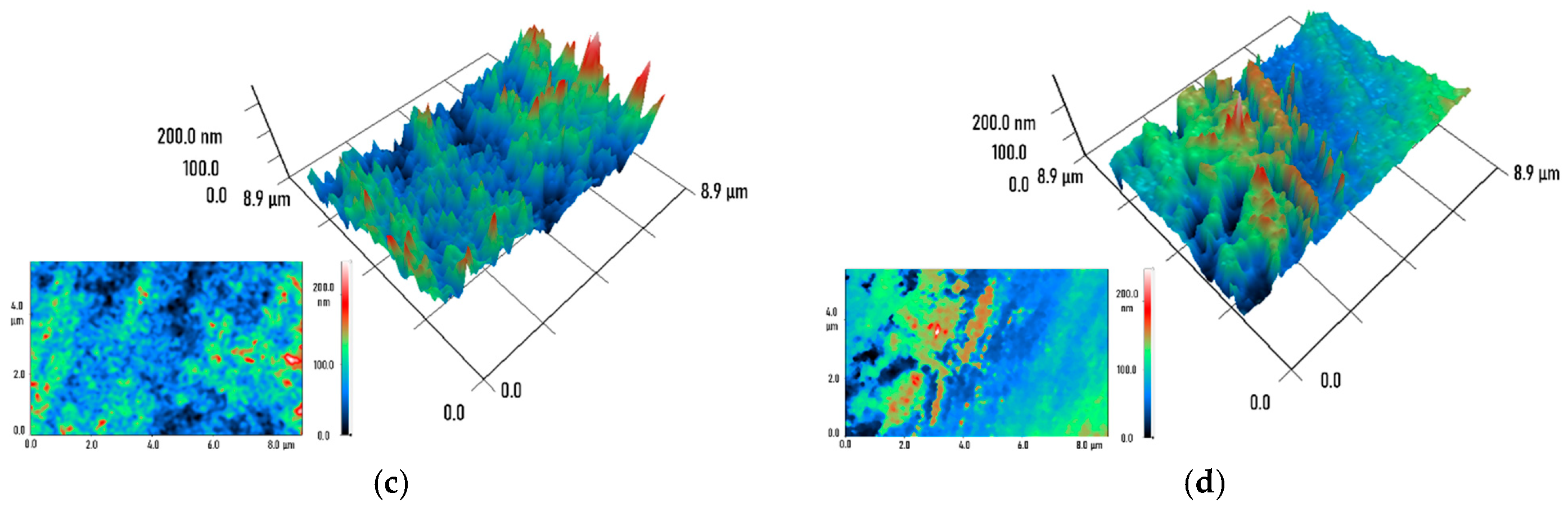

4.3. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Composites Obtained from Se NPs-MR

4.4. Quantitative Assessment of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Formation in Aqueous Solutions (·OH and H2O2)

4.5. Microbiological Assay

4.6. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

4.7. Statistical Processing and Data Visualization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| LRPS | Long-lived Reactive Protein Species |

| OD | Optical Density |

| PI | Propidium Iodide |

| Se NPs | Selenium nanoparticles |

| MR | Methacrylate Resin |

References

- Li, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhu, R.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.-C. Revolutionizing medical implant fabrication: Advances in additive manufacturing of biomedical metals. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 7, 022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, W.; Leng, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, H.; Ding, H.; Zhou, J.; Cui, L. Review and Research Prospects on Additive Manufacturing Technology for Agricultural Manufacturing. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.L.; Goh, G.L.; Goh, G.D.; Ten, J.S.J.; Yeong, W.Y. Progress and Opportunities for Machine Learning in Materials and Processes of Additive Manufacturing. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2310006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.S. Prosthodontic Applications of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): An Update. Polymers 2020, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri, B.A.; Satgunam, M.; Abreeza, N.; Abed, A.N.; Jones, I.P. A review on enhancements of PMMA Denture Base Material with Different Nano-Fillers. Cogent Eng. 2021, 8, 1875968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Kan, Y.-C.; Xu, Y.; Han, L.-Y.; Bu, W.-H.; Han, L.-X.; Qi, Y.-Y.; Chu, J.-J. Preparation and efficacy of antibacterial methacrylate monomer-based polymethyl methacrylate bone cement containing N-halamine compounds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1414005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zore, A.; Abram, A.; Učakar, A.; Godina, I.; Rojko, F.; Štukelj, R.; Škapin, A.S.; Vidrih, R.; Dolic, O.; Veselinovic, V.; et al. Antibacterial Effect of Polymethyl Methacrylate Resin Base Containing TiO2 Nanoparticles. Coatings 2022, 12, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, S.V.; Sarimov, R.M.; Astashev, M.E.; Pishchalnikov, R.Y.; Yanykin, D.V.; Simakin, A.V.; Shkirin, A.V.; Serov, D.A.; Konchekov, E.M.; Namik Guseynagaogly, G.-Z.; et al. Modern physical methods and technologies in agriculture. Phys. Uspekhi 2023, 67, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmani, A.; Kovačević, D.; Bohinc, K. Nanoparticles: From synthesis to applications and beyond. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 303, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, I.; Skalickova, S.; Sajjad, H.; Skladanka, J.; Horky, P. Uses of Selenium Nanoparticles in the Plant Production. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlamova, E.G.; Turovsky, E.A.; Blinova, E.V. Therapeutic Potential and Main Methods of Obtaining Selenium Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.A.O.; Basuini, M.F.E.; Yilmaz, S.; Abdel-Latif, H.M.R.; Kari, Z.A.; Abdul Razab, M.K.A.; Ahmed, H.A.; Alagawany, M.; Gewaily, M.S. Selenium Nanoparticles as a Natural Antioxidant and Metabolic Regulator in Aquaculture: A Review. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffrion, L.D.; Hesabizadeh, T.; Medina-Cruz, D.; Kusper, M.; Taylor, P.; Vernet-Crua, A.; Chen, J.; Ajo, A.; Webster, T.J.; Guisbiers, G. Naked Selenium Nanoparticles for Antibacterial and Anticancer Treatments. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 2660–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, A.; Dharmalingam Jothinathan, M.K.; Saravanan, S.; Tamil Selvan, S.; Rajan Renuka, R.; Srinivasan, G.P. Green Synthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles From Clove and Their Toxicity Effect and Anti-angiogenic, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Potential. Cureus 2024, 16, e55605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, J.A.; Malik, J.A.; Ahmed, S.; Manzoor, M.; Ahemad, N.; Anwar, S. Recent advances in the therapeutic applications of selenium nanoparticles. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, N.; Phalswal, P.; Khanna, P.K. Selenium nanoparticles: A review on synthesis and biomedical applications. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 1415–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, C.; Florindo, H.F.; Santos, H.A. Selenium Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications: From Development and Characterization to Therapeutics. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidin; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, T.; Wu, X.; Yuan, W.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, X.; Zi, C. Selenium and Selenoproteins: Mechanisms, Health Functions, and Emerging Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, P.-Y.; Chen Yan, Y.-M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Chen, M.-M.; Zhang, S.-E.; Zhang, X.-F. A comprehensive review on potential role of selenium, selenoproteins and selenium nanoparticles in male fertility. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlamova, E.G. Roles of selenium-containing glutathione peroxidases and thioredoxin reductases in the regulation of processes associated with glioblastoma progression. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 766, 110344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoidis, E.; Seremelis, I.; Kontopoulos, N.; Danezis, G. Selenium-Dependent Antioxidant Enzymes: Actions and Properties of Selenoproteins. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nastulyavichus, A.; Kudryashov, S.; Smirnov, N.; Saraeva, I.; Rudenko, A.; Tolordava, E.; Ionin, A.; Romanova, Y.; Zayarny, D. Antibacterial coatings of Se and Si nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 469, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenichev, I.F.; Gorchakova, N.O.; Bukhtiyarova, N.V.; Samura, I.B.; Savchenko, N.V.; Popazova, O.O. Pharmacological properties of selenium and its preparations: From antioxidant to neuroprotector. Res. Results Pharmacol. 2021, 7, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmistrov, D.E.; Shumeyko, S.A.; Semenova, N.A.; Dorokhov, A.S.; Gudkov, S.V. Selenium Nanoparticles (Se NPs) as Agents for Agriculture Crops with Multiple Activity: A Review. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Mehta, S.K. Selenium Nanomaterials: Applications in Electronics, Catalysis and Sensors. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 1658–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSheikh, S.K.; Eid, E.-S.G.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Abdelaziz, D. Physical/mechanical and antibacterial properties of composite resin modified with selenium nanoparticles. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnour, S.A.; Alagawany, M.; Hashem, N.M.; Farag, M.R.; Alghamdi, E.S.; Hassan, F.U.; Bilal, R.M.; Elnesr, S.S.; Dawood, M.A.O.; Nagadi, S.A.; et al. Nanominerals: Fabrication Methods, Benefits and Hazards, and Their Applications in Ruminants with Special Reference to Selenium and Zinc Nanoparticles. Animals 2021, 11, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivileva, O.; Pozdnyakov, A.; Ivanova, A. Polymer Nanocomposites of Selenium Biofabricated Using Fungi. Molecules 2021, 26, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Li, T.; Lu, C.; Xu, H. Selenium-Containing Polymers: Perspectives toward Diverse Applications in Both Adaptive and Biomedical Materials. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7435–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, R.; Karthick Raja Namasivayam, S.; Krithika Shree, S. A Critical Review on Nano-selenium Based Materials: Synthesis, Biomedicine Applications and Biocompatibility Assessment. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2024, 34, 3037–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarosi, C.; Moldovan, M.; Soanca, A.; Roman, A.; Gherman, T.; Trifoi, A.; Chisnoiu, A.M.; Cuc, S.; Filip, M.; Gheorghe, G.F.; et al. Effects of Monomer Composition of Urethane Methacrylate Based Resins on the C=C Degree of Conversion, Residual Monomer Content and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, Y.; Kozlov, V.; Burmistrov, D.; Fedyakova, N.; Bermeshev, M.; Chapala, P. Comprehensive investigation of phosphine oxide photoinitiators for vat photopolymerization. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 8405–8418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Xiao, R.; Afolabi, M.; Bomma, M.; Xiao, Z. Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity of Selenium Nanoparticles against Food-Borne Pathogens. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionin, A.A.; Ivanova, A.K.; Khmel’nitskii, R.A.; Klevkov, Y.V.; Kudryashov, S.I.; Levchenko, A.O.; Nastulyavichus, A.A.; Rudenko, A.A.; Saraeva, I.N.; Smirnov, N.A.; et al. Antibacterial effect of the laser-generated Se nanocoatings on Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Laser Phys. Lett. 2018, 15, 015604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfileva, A.I.; Moty’leva, S.M.; Klimenkov, I.V.; Arsent’ev, K.Y.; Graskova, I.A.; Sukhov, B.G.; Trofimov, B.A. Development of Antimicrobial Nano-Selenium Biocomposite for Protecting Potatoes from Bacterial Phytopathogens. Nanotechnologies Russ. 2018, 12, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraeva, I.N.; Tolordava, E.R.; Khmelnitsky, R.A.; Shelygina, S.N.; Pozdnyakova, D.S.; Nastulyavichus, A.A.; Rimskaya, E.N.; Rupasov, A.E. Effect of Selenium, Copper and Silver Microparticles Obtained in Viscous Media on the Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria Survival. JETP Lett. 2025, 121, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimler, I.V.; Simakin, A.V.; Dorokhov, A.S.; Gudkov, S.V. Mini-review on laser-induced nanoparticle heating and melting. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1463612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, M.; Haro-Poniatowski, E.; Morales, J.; Batina, N. Synthesis of selenium nanoparticles by pulsed laser ablation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2002, 195, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, O.A.; Abdulkareem, F.A.; Mohammed, A.S.; Kareem, O.A. Produce of Selenium Nanoparticles by Pulsed Laser Ablation for Anticancer Treatments. Int. J. Nanosci. 2022, 20, 2150055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado, H.A.; Gutierrez-Velasquez, E.I.; Gil, L.D.; de Camargo, I.L. Exploring the advantages and applications of nanocomposites produced via vat photopolymerization in additive manufacturing: A review. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2023, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Khan, K.H.; Parvez, M.M.H.; Irizarry, N.; Uddin, M.N. Polymer Nanocomposites with Optimized Nanoparticle Dispersion and Enhanced Functionalities for Industrial Applications. Processes 2025, 13, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folorunso, O.; Hamam, Y.; Sadiku, R.; Kupolati, W. Effects of Defects on the Properties of Polymer Nanocomposites: A Brief Review. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2024, 34, 5667–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoudis, P.N.; Karapanagiotis, I. Modification of the wettability of polymer surfaces using nanoparticles. Prog. Org. Coat. 2014, 77, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.; Radzanowski, A.N.; Wang, C.-Y.; Mu, Y.; Coughlin, E.B.; Gorte, R.J.; Vohs, J.M.; Lee, D. Modulating the Contact Angle between Nonpolar Polymers and SiO2 Nanoparticles. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 8554–8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Xie, L.; Shi, C.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, H. Interactions between elemental selenium and hydrophilic/hydrophobic surfaces: Direct force measurements using AFM. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 303, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Ullah, A.; Azher, K.; Rehman, A.U.; Juan, W.; Aktürk, N.; Tüfekci, C.S.; Salamci, M.U. Vat photopolymerization-based 3D printing of polymer nanocomposites: Current trends and applications. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 1456–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, L.D.; Monteiro, S.N.; Colorado, H.A. Polymer Matrix Nanocomposites Fabricated with Copper Nanoparticles and Photopolymer Resin via Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2024, 16, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Hamel, C.M.; Mu, X.; Kuang, X.; Guo, Z.; Qi, H.J. Evolution of material properties during free radical photopolymerization. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2018, 112, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Hirner, S.; Wiesbrock, F.; Fuchs, P. A Review on Modeling Cure Kinetics and Mechanisms of Photopolymerization. Polymers 2022, 14, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Paul, T.; Brehm, J.; Völkl, M.; Jérôme, V.; Freitag, R.; Laforsch, C.; Greiner, A. Role of Residual Monomers in the Manifestation of (Cyto)toxicity by Polystyrene Microplastic Model Particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9925–9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić, M.; Stanojević, J.; Tačić, A.; Gligorijević, N.; Nikolić, L.; Nikolić, V.; Igić, M.; Bradić Vasić, M. Determination of residual monomer content in dental acrylic polymers and effect after tissues implantation. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2020, 34, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truffier-Boutry, D.; Demoustier-Champagne, S.; Devaux, J.; Biebuyck, J.-J.; Mestdagh, M.; Larbanois, P.; Leloup, G. A physico-chemical explanation of the post-polymerization shrinkage in dental resins. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, U.; Haider, S.; Haider, A.; Khan, N.; Alghyamah, A.A.; Jamila, N.; Khan, M.I.; Almasry, W.A.; Kang, I.-K. Biocompatible Polymers and their Potential Biomedical Applications: A Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 3608–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, B.K.; Rudolph, M.; Pechtl, M.; Wildenburg, G.; Hayden, O.; Clausen-Schaumann, H.; Sudhop, S. mSLAb—An open-source masked stereolithography (mSLA) bioprinter. HardwareX 2024, 19, e00543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajay, R.; Suma, K.; Ali, S. Monomer modifications of denture base acrylic resin: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2019, 11, S112–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, G.; Emik, S.; Yalcinyuva, T.; Sunbuloğlu, E.; Bozdag, E.; Unalan, F. The Effects of Cross-Linking Agents on the Mechanical Properties of Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) Resin. Polymers 2023, 15, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, G.I.; Ndudi, W.; Ali, A.B.M.; Yousif, E.; Zainulabdeen, K.; Onyibe, P.N.; Akpoghelie, P.O.; Ekokotu, H.A.; Isoje, E.F.; Igbuku, U.A.; et al. An updated review on the modifications, recycling, polymerization, and applications of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 20496–20539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Gutiérrez, S.; Dalle Vacche, S.; Vitale, A.; Ladmiral, V.; Caillol, S.; Bongiovanni, R.; Lacroix-Desmazes, P. Photoinduced Polymerization of Eugenol-Derived Methacrylates. Molecules 2020, 25, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhong, M.; Johnson, J.A. Light-Controlled Radical Polymerization: Mechanisms, Methods, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10167–10211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belov, S.V.; Danyleiko, Y.K.; Glinushkin, A.P.; Kalinitchenko, V.P.; Egorov, A.V.; Sidorov, V.A.; Konchekov, E.M.; Gudkov, S.V.; Dorokhov, A.S.; Lobachevsky, Y.P.; et al. An Activated Potassium Phosphate Fertilizer Solution for Stimulating the Growth of Agricultural Plants. Front. Phys. 2021, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, S.V.; Gudkova, O.Y.; Chernikov, A.V.; Bruskov, V.I. Protection of mice against X-ray injuries by the post-irradiation administration of guanosine and inosine. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2009, 85, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmanova, E.E.; Goncharov, R.G.; Bruskov, V.I.; Novoselov, V.I.; Sharapov, M.G. The Radioprotective Effect of Exogenous Peroxiredoxin 6 in Mice Exposed to Different Doses of Whole-Body Ionizing Radiation. Biophysics 2025, 69, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankin, V.Z.; Shumaev, K.B.; Medvedeva, V.A.; Tikhaze, A.K.; Konovalova, G.G. Mechanisms of Antioxidant Protection of Low-Density Lipoprotein Particles Against Free Radical Oxidation. Biochemistry 2025, 90, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranova, E.N.; Kononenko, N.V.; Lapshin, P.V.; Nechaeva, T.L.; Khaliluev, M.R.; Zagoskina, N.V.; Smirnova, E.A.; Yuorieva, N.O.; Raldugina, G.N.; Chaban, I.A.; et al. Superoxide Dismutase Premodulates Oxidative Stress in Plastids for Protection of Tobacco Plants from Cold Damage Ultrastructure Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhimak, S.; Baryshev, M.; Malyshko, V.; Dorohova, A.; Il’chenko, G.; Tekutskaya, E. 8-Oxoguanine-DNA-Glycosylase Gene Polymorphism and the Effects of an Alternating Magnetic Field on the Sensitivity of Peripheral Blood. Front. Biosci. Landmark 2023, 28, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viel, A.; Bruselles, A.; Meccia, E.; Fornasarig, M.; Quaia, M.; Canzonieri, V.; Policicchio, E.; Urso, E.D.; Agostini, M.; Genuardi, M.; et al. A Specific Mutational Signature Associated with DNA 8-Oxoguanine Persistence in MUTYH-defective Colorectal Cancer. EBioMedicine 2017, 20, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, X. The Significance of 8-oxoGsn in Aging-Related Diseases. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentkowska, A.; Pyrzyńska, K. Antioxidant Properties of Selenium Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Tea and Herb Water Extracts. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pan, Y.; Liu, X.; Han, Z.; Chen, S. Constructing Selenium Nanoparticles with Enhanced Storage Stability and Antioxidant Activities via Conformational Transition of Curdlan. Foods 2023, 12, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentkowska, A.; Pyrzyńska, K. The Influence of Synthesis Conditions on the Antioxidant Activity of Selenium Nanoparticles. Molecules 2022, 27, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, S.V.; Gao, M.; Simakin, A.V.; Baryshev, A.S.; Pobedonostsev, R.V.; Baimler, I.V.; Rebezov, M.B.; Sarimov, R.M.; Astashev, M.E.; Dikovskaya, A.O.; et al. Laser Ablation-Generated Crystalline Selenium Nanoparticles Prevent Damage of DNA and Proteins Induced by Reactive Oxygen Species and Protect Mice against Injuries Caused by Radiation-Induced Oxidative Stress. Materials 2023, 16, 5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, X.; Gong, Y.; Yuan, G.; Cen, J.; Lie, Q.; Hou, Y.; Ye, G.; Liu, S.; Liu, J. Porous selenium nanozymes targeted scavenging ROS synchronize therapy local inflammation and sepsis injury. Appl. Mater. Today 2021, 22, 100929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumore, N.S.; Mukhopadhyay, M. Antioxidant properties of aqueous selenium nanoparticles (ASeNPs) and its catalysts activity for 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) reduction. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1205, 127637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Barbosa, M.T.; Mejía Diaz, L.F.; Wrobel, K.; Corrales Escobosa, A.R.; Miranda-Aviles, R.; Wrobel, K. Selenium Nanoparticles Act as Hydrogen Peroxide Scavengers in a Simulated Biological Environment. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202500433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzadeh, M.; Sadeghi Sangdehi, S.A.; Salimizand, H.; Rahimi, F.; Nouri, B. Evaluating the anti-Candida effects of selenium nanoparticles impregnated in acrylic resins: An in vitro study. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2024, 18, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, Q.; Yu, Q.; Sun, D.; Liu, J. Investigation of functional selenium nanoparticles as potent antimicrobial agents against superbugs. Acta Biomater. 2016, 30, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, S.J.; Sheng, J.; Hosseinian, F.; Willmore, W.G. Nanoparticle Effects on Stress Response Pathways and Nanoparticle–Protein Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.; Wang, Q.; Larese-Casanova, P. Inhibition of various gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria growth on selenium nanoparticle coated paper towels. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 2015, 2885–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremonini, E.; Zonaro, E.; Donini, M.; Lampis, S.; Boaretti, M.; Dusi, S.; Melotti, P.; Lleo, M.M.; Vallini, G. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles: Characterization, antimicrobial activity and effects on human dendritic cells and fibroblasts. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, A.E.; Ahmed, E.H.; Awad, H.M.; Ayoub, M.M.H. Synthesis and cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles incorporated nano-chitosan. Polym. Bull. 2023, 81, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Lou, X.; Jiao, J.; Li, Y.; Dai, K.; Jia, X. Preliminary Structural Characterization of Selenium Nanoparticle Composites Modified by Astragalus Polysaccharide and the Cytotoxicity Mechanism on Liver Cancer Cells. Molecules 2023, 28, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, I.; Rana, N.F.; Tanweer, T.; Arif, W.; Shafique, I.; Alotaibi, A.S.; Almukhlifi, H.A.; Alshareef, S.A.; Menaa, F. Effectiveness of Se/ZnO NPs in Enhancing the Antibacterial Activity of Resin-Based Dental Composites. Materials 2022, 15, 7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorudko, I.V.; Grigorieva, D.V.; Gusakov, G.A.; Baran, L.V.; Reut, V.E.; Sak, E.V.; Baimler, I.V.; Simakin, A.V.; Dorokhov, A.S.; Izmailov, A.Y.; et al. Rod and spherical selenium nanoparticles: Physicochemical properties and effects on red blood cells and neutrophils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 2025, 1869, 130777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-1:2018; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Sevostyanov, M.A.; Kolmakov, A.G.; Sergiyenko, K.V.; Kaplan, M.A.; Baikin, A.S.; Gudkov, S.V. Mechanical, physical–chemical and biological properties of the new Ti–30Nb–13Ta–5Zr alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 14516–14529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimler, I.V.; Gudkov, S.V.; Matveeva, T.A.; Simakin, A.V.; Shcherbakov, I.A. Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species during Water Drops Fall on a Solid Surface. Phys. Wave Phenom. 2024, 32, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernikov, A.V.; Gudkov, S.V.; Shtarkman, I.N.; Bruskov, V.I. Oxygen effect in heat-induced DNA damage. Biofizika 2007, 52, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, S.V.; Shtarkman, I.N.; Chernikov, A.V.; Usacheva, A.M.; Bruskov, V.I. Guanosine and inosine (riboxin) eliminate the long-lived protein radicals induced X-ray radiation. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 413, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmistrov, D.E.; Simakin, A.V.; Smirnova, V.V.; Uvarov, O.V.; Ivashkin, P.I.; Kucherov, R.N.; Ivanov, V.E.; Bruskov, V.I.; Sevostyanov, M.A.; Baikin, A.S.; et al. Bacteriostatic and Cytotoxic Properties of Composite Material Based on ZnO Nanoparticles in PLGA Obtained by Low Temperature Method. Polymers 2021, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmistrov, D.E.; Serov, D.A.; Baimler, I.V.; Gritsaeva, A.V.; Chapala, P.; Simakin, A.V.; Astashev, M.E.; Karmanova, E.E.; Dubinin, M.V.; Nizameeva, G.R.; et al. Polymethyl Methacrylate-like Photopolymer Resin with Titanium Metal Nanoparticles Is a Promising Material for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burmistrov, D.E.; Baimler, I.V.; Yanbaev, F.M.; Astashev, M.E.; Kozlov, V.A.; Serov, D.A.; Simakin, A.V.; Gudkov, S.V. Methacrylic Photopolymerizable Resin Incorporating Selenium Nanoparticles as a Basis for Additive Manufacturing of Functional Materials with Unique Biological Properties. Inorganics 2025, 13, 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13110365

Burmistrov DE, Baimler IV, Yanbaev FM, Astashev ME, Kozlov VA, Serov DA, Simakin AV, Gudkov SV. Methacrylic Photopolymerizable Resin Incorporating Selenium Nanoparticles as a Basis for Additive Manufacturing of Functional Materials with Unique Biological Properties. Inorganics. 2025; 13(11):365. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13110365

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurmistrov, Dmitriy E., Ilya V. Baimler, Fatikh M. Yanbaev, Maxim E. Astashev, Valeriy A. Kozlov, Dmitry A. Serov, Aleksandr V. Simakin, and Sergey V. Gudkov. 2025. "Methacrylic Photopolymerizable Resin Incorporating Selenium Nanoparticles as a Basis for Additive Manufacturing of Functional Materials with Unique Biological Properties" Inorganics 13, no. 11: 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13110365

APA StyleBurmistrov, D. E., Baimler, I. V., Yanbaev, F. M., Astashev, M. E., Kozlov, V. A., Serov, D. A., Simakin, A. V., & Gudkov, S. V. (2025). Methacrylic Photopolymerizable Resin Incorporating Selenium Nanoparticles as a Basis for Additive Manufacturing of Functional Materials with Unique Biological Properties. Inorganics, 13(11), 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13110365