Abstract

In this article, one-dimensional photonic crystal cavities on bending waveguides (PCCoBW) used for achieving high-contrast spectra are proposed, analyzed, and experimentally verified on silicon on insulator (SOI). Both air and dielectric modes of the PCCoBW calculated by the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method show finger-ring-like mode profiles with the achievement of high-quality factors (Q∼106), even when the bending radius is less than 50 times the lattice constant. Straight waveguides side-coupled to the cavity are used to access and measure mode resonances. The measured spectra show a high extinction ratio over 40 dB for dielectric modes and 20 dB for air modes, respectively. Both dielectric and air resonant modes are revealed with Q-factors over 3.3 × 104 and 7.9 × 104, respectively, for the coupled PCCoBWs. The proposed PCCoBW could be implemented as high-contrast notch filtering and would benefit a broad range of applications such as optical filters, modulators, sensors, or switches.

1. Introduction

By exploiting the design principles of photonic crystals [1,2,3,4], photonic crystal nanocavities can exhibit exceptional performance, characterized by an ultra-high quality factor () and an ultrasmall modal volume V, typically around . A one-dimensional photonic crystal cavity (or nanobeam photonic crystal cavity, NPCC) constructed on a periodic hole nanobeam not only has an ultra-high [5,6] but also renders an ultra-compact waveguide geometry suitable for high integration. The ultra-high metric means ultralow power consumption, ultrafast operation speed, and ultra-strong light–matter interaction [7]. On-chip applications, including lasers [8], filters [9], modulators [10], switches [11], and sensors [12,13], have been demonstrated on silicon on insulator (SOI), SiN, AlN, InP, GaAs, GaN, LiNbO3, SiC, diamond, polymer, or chalcogenide. The fundamental cavity–waveguide configurations involved in these aforementioned NPCC applications are mainly classified into in-line coupling [14] and side-coupling [15,16]. Although finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulation predicts the high transmission of an optimized in-line coupling nanobeam photonic crystal cavity, the recorded experimental transmission is only −1.5 dB under ambient air-cladding [14]. For silica-encapsulated NPCCs, the reported insert loss is relatively high, with a typical value being under −10 dB [17].

Side-coupled NPCCs, however, provide high baseline transmission for non-resonant waves through the output port while sustaining high Q. They demonstrate attractive capabilities, such as serial integration, add/drop filtering [18], and multiplexing [12,13], which are not readily attainable from in-line devices. However, due to the inherent geometry limitation of straight nanobeams, the parallel side-coupling does not offer a suitable way to realize a high extinction ratio at a resonant wavelength. A theoretical study suggests that momentum space matching could be used to implement suitable coupling [19]. Up to now, the demonstrated side-coupled NPCC filters only show an extinction ratio (ER) with a transmission lower than 4.2 dB on resonance [20], which is insufficient for many applications such as switches, wavelength division demultiplexing (WMD) filters, modulators, and sensors. Using an S-bend bus waveguide is another way to implement efficient side-coupling of NPCC filters [15]. However, the insertion loss of the through wave will accumulate in the bus waveguide when multiple serially side-coupled NPCCs are involved.

This work demonstrates one-dimensional photonic crystal cavities on a ring (PCCoBW) on SOI. Utilizing the enhanced exposure of evanescent fields of bending resonant modes, we achieve filters with ERs around −40 dB and . Furthermore, the coupling gap is relaxed to above 200 nm, which is more feasible for fabrication. As far as we know, these results represent the highest ER and Q observed in side-coupled NPCCs.

2. Proposal and Analysis

The schematic models of a side-coupled conventional and bending NPCC are shown in Figure 1a and Figure 1b, respectively. By using the temporal coupling mode theory, the transmission through the output port can be described as [21]:

where is the resonant frequency of the side-coupled NPCC and and represent the coupling rates at which the NPCC couples to the bus waveguide and the radiation modes, respectively. The partial quality factor is related to the coefficients of the coupling rate by , where i represents a certain coupling channel i and the total quality factor can be expressed as .

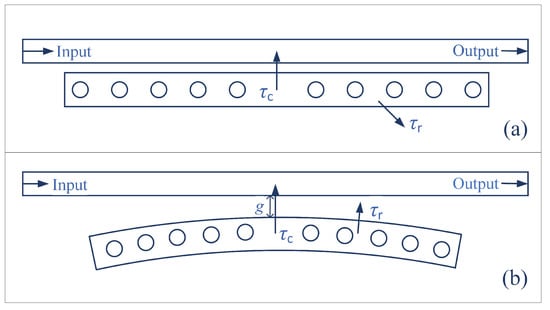

Figure 1.

Schematics of the side-coupled (a) conventional NPCC and (b) bending NPCC.

Compared to the conventional side-coupled NPCC (Figure 1a), the proposed configuration attains a natural adiabatic coupling structure, which could efficiently decrease the reflection and the insertion loss of non-resonant waves. From Equation (1), to achieve complete extinction at resonance (critical coupling), one should ensure that or . Our previous work [22] indicates that both the and of the structure in Figure 1a will increase when the coupling gap g decreases. Fundamentally, the bandgap of the compound periodic waveguide composed of the parallel bus waveguide and nanobeam will shrink and even disappear when g becomes small. It has been proven [20] that implementing a high-contrast-on-resonance notch filter using the parallel coupled configurations is intractable (Figure 1a). For critical coupling, sustaining a high for small gap g (small ) is important. Figure 1b provides a possible design that alleviates the degradation of when g is small.

Firstly, we employ the FDTD simulation to investigate the influence of radius R of the bending nanobeam cavity on the partial of the bending NPCCs. In the simulations, we assume that the NPCCs are fabricated on a 220 nm silicon layer SOI platform. The bending nanobeam is 500 nm wide with a bending radius , where is the normalized bending radius and a is the lattice constant. Here a is 340 nm, and the radii of the periodic holes vary linearly, starting from the hole with radius and decreasing to both sides of the cavity to the radius of hole . The calculation is started from a straight nanobeam photonic crystal cavity with a number of holes = 40. The fundamental transverse electric (TE) polarization mode of this cavity shows an intrinsic . To investigate the influence on the Qs of the bending radius R and coupling gap g, we calculate the partial using the following equation

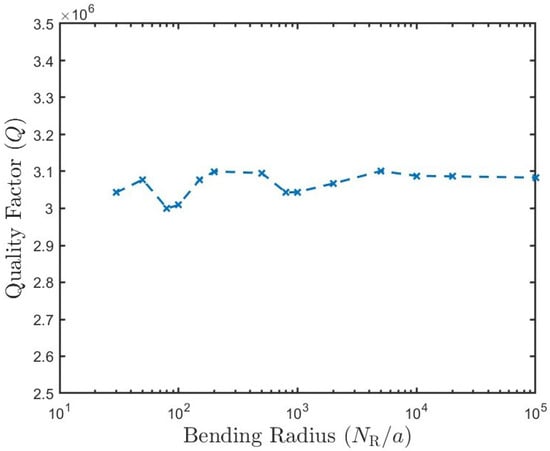

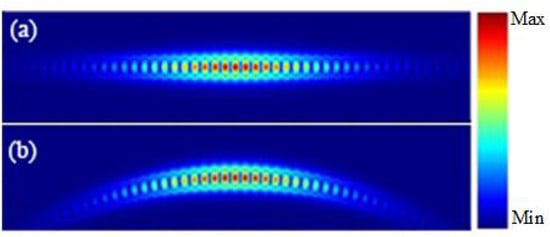

where U is the energy of the resonant modes stored in the cavity, is the power loss per cycle due to some of the coupling mechanisms in channel i, and is the resonant frequency of the resonant mode. Figure 2 reveals the essential fact that Q of the unloaded bending NPCC could remain around the initial value even when the bending radius R decreases from 100,000a to 30a. The mode profiles of the conventional NPCC and bending NPCC with are shown in Figure 3. The mode distribution (E intensity) of the NPCC with does not show noticeable radiation loss compared to that of the straight nanobeam cavity.

Figure 2.

Influence of bending radius on quality factor Q of the bending NPCs.

Figure 3.

Mode profiles of (a) a conventional NPCC and (b) the bending NPCC.

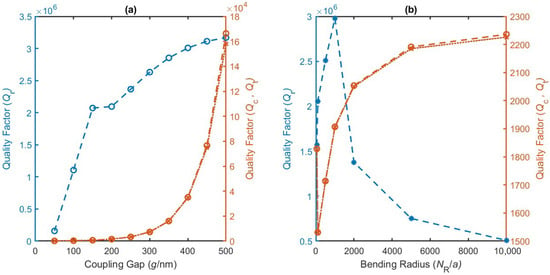

To investigate the ER of the spectral dip at the resonance of the coupled bending NPCC, the calculated partial Qs according to Equation (2) are shown in Figure 4. At the coupling gap of 200 nm, increase gradually when the nanobeam cavity bends outside away from the bus waveguide, and achieve a maximum of when takes 1500. Further bending the nanobeam decreases the slightly since dramatic radiation loss occurs. However, sees a rapid increase when changes from 50 to 4000 and gradually saturates to 2300 when increases above 10,000. It is worth noting that a smaller bending radius would increase the since an insufficient coupling region is ensured. Thus a moderately small is critical for implementing high-efficient side-coupling. From the data in Figure 4b, choosing a bending radius between – for ER > 30 dB is suitable.

Figure 4.

Partial Qs (: blue circled dash; : brown circled dash; : dotted) of the side-coupled bending NPCC as a function of (a) coupling gap g (with fixed ) and (b) bending radius (with fixed nm).

When the is fixed at 100, the dependencies of and on g are shown in Figure 4a. Both and rise with the increasing coupling gap g. Specifically, increases rapidly for smaller g until 200 nm, whereas increases rapidly when g is greater than 300 nm. In situations where (e.g., number of holes and < 16), the two ends of a bending nanobeam cavity overlap and naturally form a photonic crystal cavity on the bending waveguide (PCCoBW). It should be noted that the mechanism of the proposed PCCoBW is totally different from those photonic crystal ring resonators (PCRRs) in refs. [23,24,25,26], where a bending periodic (rotational symmetry) holey waveguide is used to replace the traditional waveguide of a ring resonator. By creating two cavity centers, the PCCoBW can simultaneously support dielectric and air resonant modes. In this case, the dielectric and air mode cavities share the same multiple periodic air holes, where the interplay between the two distinct resonances could increase in case of sufficient mode overlap.

3. Device Design

The proposed PCCoBWs on a 220 nm silicon layer are modeled and analyzed using the 3D FDTD with the waveguide parameters given in Section 2. takes 50 and 70, corresponding to of 15.91 and 22.28, respectively. The radii of air holes vary from to and the lattice is 340 nm in both cases. The final design includes air and dielectric resonant modes coexisting in bending nanobeam cavities coupled, respectively, with two access waveguides. The parameters used in the simulation and the results are summarized and listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Parameters used and results achieved in the simulations ( = 50, = 15.92).

Table 2.

Parameters used and results achieved in the simulations ( = 70, = 22.28).

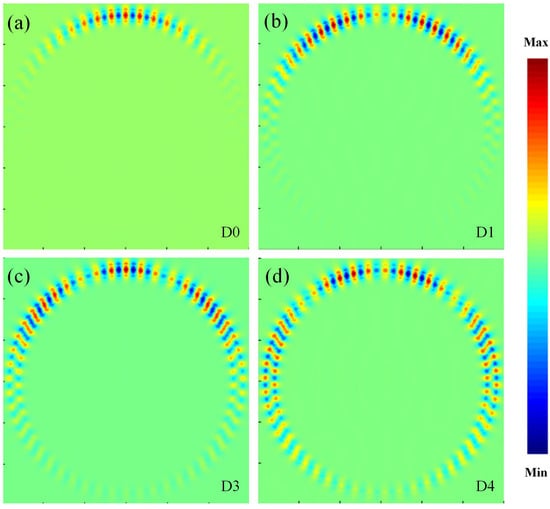

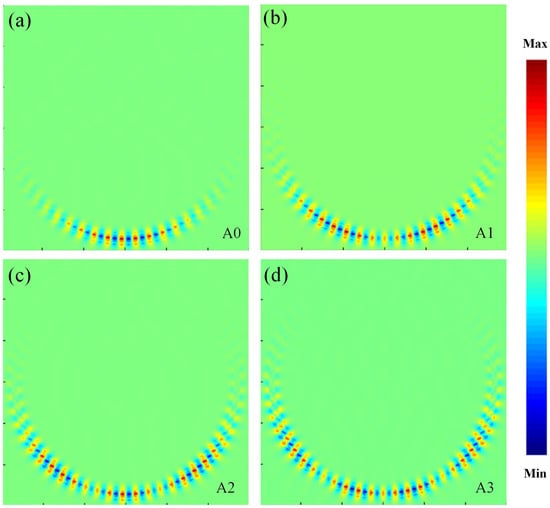

In the simulations, only the first four orders of TE polarization resonant modes are investigated, but they may represent the key metrics of these proposed PCCoBWs. Table 1 and Table 2 show that modal volumes V of the designed cavities are comparable to those of conventional nanobeam photonic crystal cavities, typically with several times the , where is the resonant wavelength and n is the refractive index of the cavity center where the strongest electric field is located. The air mode cavity has a slightly lower V and higher Q than the dielectric modes since smaller holes are created in the cavity center, and better mode confinement is achieved. Both the air mode and dielectric mode have much slower V than those of photonic crystal ring resonators [23,24,25,26]. The mode profiles simulated by 3D FDTD of the dielectric and air modes ( = 50) are illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively. The corresponding mode numbers are also marked with the modes for comparison. These figures show that air and dielectric modes with high Q values are well confined in the bending PCCoBWs. In the profiles of high-order modes [Figure 5c,d and Figure 6c,d], one can also observe the mode conversion from fundamental modes to first-order modes arising along the ring due to the waveguide bend. Comparing the mode profiles of air and dielectric modes, we can also see significant differences in mode-extending abilities along the ring. Specifically, the mode tail of the dielectric modes extends further to the opposite side of the ring than that of air modes.

Figure 5.

Mode profiles of the (a) D0, (b) D1, (c) D2 and (d) D3 order dielectric modes of the unloaded PCCoBW ( = 50).

Figure 6.

Mode profiles of the (a) A0, (b) A1, (c) A2 and (d) A3 order air modes of the unloaded PCCoBW ( = 50).

For the convenience of device characterization, two access waveguides with focusing sub-wavelength grating couplers are placed alongside the two cavity centers for coupling signal light into and out of the PCCoBW. To achieve better mode coupling, the access waveguides with various widths are chosen to match the effective refractive indexes of the air mode and dielectric mode of the holey waveguides, respectively. The details of the mode-matching design can be found in our earlier work [27].

4. Experiment and Discussion

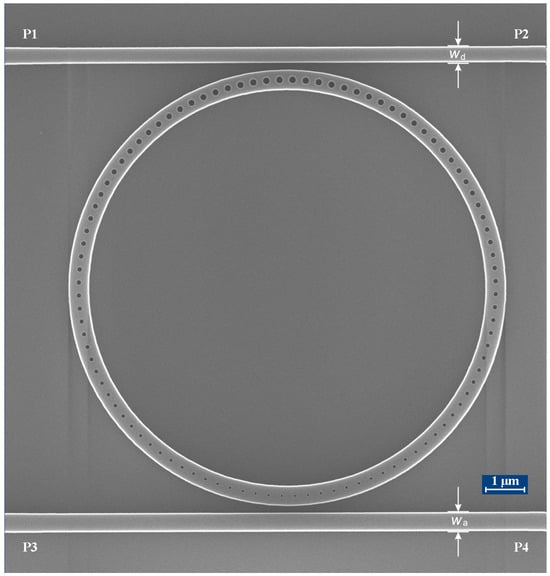

A 100 keV electron beam lithography system and anisotropic plasma etch process are employed to provide smooth sidewalls and reduce the propagation loss of waveguides. Checking with a scanning electronic microscope (SEM) is conducted before a 2.2 μm thick cladding oxide layer is deposited on the top of etched devices. A typical SEM image of the fabricated PCCoBW ( = 50) is shown in Figure 7. Note that imperfection of the process would have influenced the critical size of the final devices, particularly the smaller holes. We also fabricated PCCoBWs with a larger bending radius ( = 22.28) and number ( = 70) of mirror air holes. The final silica-clad, fully etched 220 nm SOI devices were tested using a low-source spontaneous emission (SSE) tunable sweeping laser (Keysight 81960A, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) and a multi-channel optical power meter (Keysight N7745A, Santa Rosa, CA, USA). The response spectra of the through and drop ports which were excited from various input ports are plotted in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10. The transmission spectrum of a straight waveguide has been used to calibrate the baseline of the response spectra.

Figure 7.

An SEM image of the fabricated PCCoBW on SOI ( = 50, a = 340 nm, = 390 nm, = 480 nm).

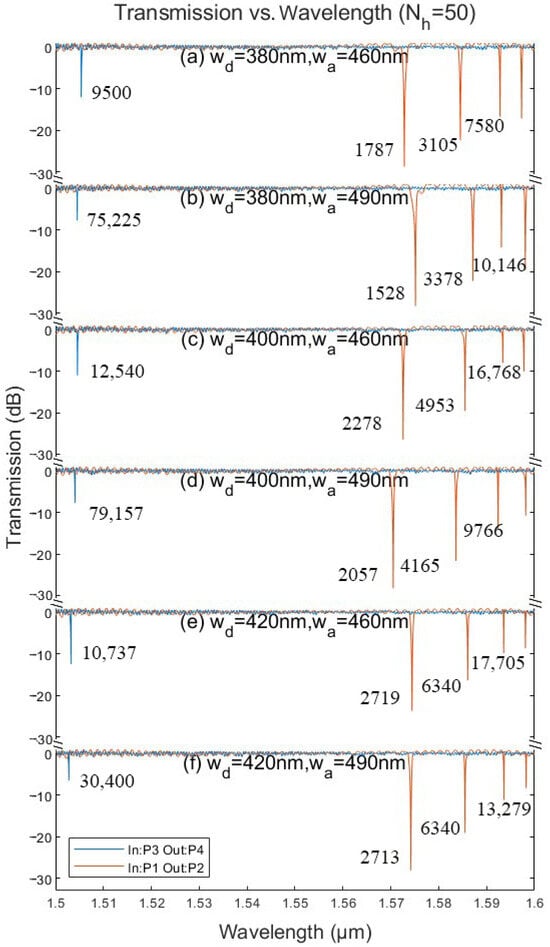

Figure 8.

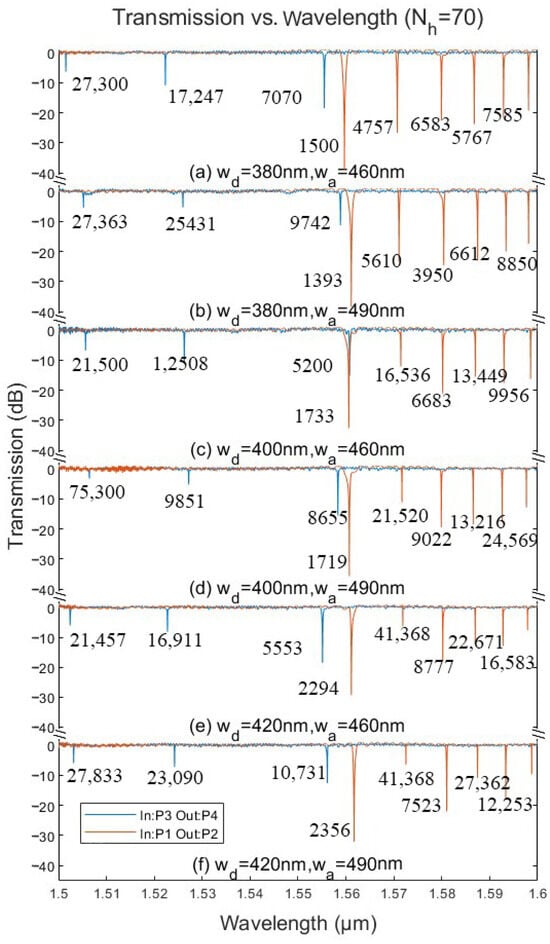

Measured spectra of the through ports of the fabricated PCCoBW with = 50. The value labeled adjacent to the transmission dip corresponds to the Q factor of the resonance. (a) = 380 nm and = 460 nm, (b) = 380 nm and = 490 nm, (c) = 400 nm and = 460 nm, (d) = 400 nm and = 490 nm, (e) = 420 nm and = 460 nm, (f) = 420 nm and = 490 nm.

Figure 9.

Measured spectra of the through ports of the fabricated PCCoBW with = 70. The value labeled adjacent to the transmission dip corresponds to the Q factor of the resonance. (a) = 380 nm and = 460 nm, (b) = 380 nm and = 490 nm, (c) = 400 nm and = 460 nm, (d) = 400 nm and = 490 nm, (e) = 420 nm and = 460 nm, (f) = 420 nm and = 490 nm.

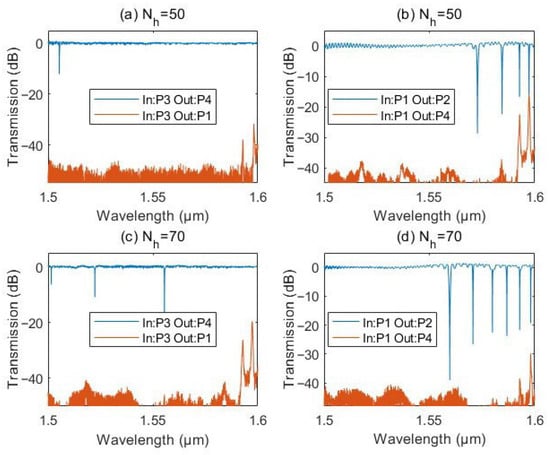

Figure 10.

Measured spectra of the through and drop ports of the fabricated PCCoBWs with (a,b) = 50 and (c,d) = 70 holes.

As shown in Figure 8, the fundamental air resonance presents a greater redshift ( nm) in spectra relative to the simulation results compared with those of the dielectric modes ( nm). It is also observed that as increases (Figure 9), the measured resonance shift () in the air mode rises ( nm), while the wavelength shift in the dielectric mode remains essentially stable (∼16 nm). The influences of fabrication errors on Q and have been systematically studied by Yamaguchi, Yuki et al. [28], and experimentally. Such substantial discrepancy has been confirmed to be mostly caused by the fabrication error of tiny structures such as small holes [15]. The layout for the fabricated device is a ring waveguide with an array of subtracted holes, which are defined in the Klayout design file as polygonal shapes. Each hole is constructed as a polygon with more than 150 vertices to achieve a high degree of geometric precision in the mask design. Therefore, the air mode is more susceptible to variations in the size of small holes that form the center of the air mode compared to the dielectric mode.

For the = 50 case, an ER of more than 30 dB of the dielectric mode resonance is observed in the measured spectra, whereas a maximum ER of only 12 dB is found for air mode resonances. Comparing various subplots in Figure 8, one may find that the mode matching between the PCCoBW and the coupling waveguides plays significant roles in waveguide–cavity coupling coefficients, which substantially influence the ER of the corresponding resonance spectra. Specifically, for the dielectric mode coupling waveguide, the width = 380 nm configuration provides the best coupling, while the waveguide width = 460 nm is the most compelling case for air resonances. Similar results are also found in the measured spectra of the case, as shown in Figure 9. The Q factors of these modes are also marked near the dip of the resonant spectra. The typical Q is and for the fundamental air and dielectric resonant modes, respectively. Since these Qs are measured from the coupled PCCoBWs, the intrinsic (standalone PCCoBW) Qs are supposed to be higher than .

Figure 9a reveals an ER over 40 dB for the dielectric resonant mode at 1572.3 nm, representing the recorded ER observed in side-coupled PCCoBWs. The ER of the corresponding air mode resonances also rises to 20 dB. These improvements should be attributed to a larger bending radius, thus ensuring stronger coupling. Figure 9c–f also show another essential characteristic of the side-coupled bending PCCoBWs: mode-related coupling strength fluctuations. Combining the mode profiles in Figure 5 and Figure 6 and noticing the differences between the symmetric and anti-symmetric modes, the resonance dips also reveal the corresponding coupling strengths and ERs. The distinct resonance dip indicates that mode overlapping in space is an essential factor influencing the coupling. When the mode is symmetric, the max field is located at the center of the coupling region and the max ER is obtained (Figure 9e,f), and vice versa.

We also measured the responses of the drop ports of these PCCoBWs, and the results are reported in Figure 10. It can be seen that mode-dependent coupling also plays a significant role in the responses of the drop ports. As shown in Figure 10a,d, no apparent air mode resonances can be found on the spectra of the drop ports when P3 serves as the input port, whereas high-order dielectric resonant modes are revealed when either P1 or P3 are used as the input port (Figure 10b,c). The reason causing this difference can be understood by comparing the mode profile distributions in Figure 5 and Figure 6 for dielectric modes and air modes, respectively. The high-order dielectric modes extend to the cavity center of the other coupling region much more than the air modes, due to larger holes that lower confinement. The mode extension increases the mode overlay, resulting in a higher coupling strength with the drop waveguide.

5. Conclusions

In summary, 1D photonic crystal cavities on rings (PCCoBW) have been proposed and investigated. The air and dielectric modes of the bending PCCoBW can sustain high-quality factors approaching , even when the bending radius is less than . The experimental results conducted on SOI indicate that high ER over 40 dB and 20 dB can be achieved in the = 22 case for dielectric and air resonant modes, respectively, when suitable mode matching is satisfied in dual-bus coupled PCCoBW configurations. The PCCoBW also shows the essential characteristics of mode-dependent coupling strength, distinct from conventional microring resonators or photonic crystal ring resonators. We hope that these findings will contribute to the development of low-power-consumption switches and high-performance filters and sensors, as well as engineering the interactions between air and dielectric resonant modes.

Author Contributions

Validation, H.Q. and D.K.; Investigation, P.Y.; Data curation, Z.W. and J.W.; Writing—original draft, P.Y., J.W. and F.G.; Writing—review & editing, F.G., H.Q. and D.K.; Supervision, P.C.; Project administration, P.C.; Funding acquisition, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Program of the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education (Y202456638), the Science and Technology Innovation Yongjiang 2035 Key Research and Development Program (2025Z089), and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian (2023J01350).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yablonovitch, E. Inhibited Spontaneous Emission in Solid-State Physics and Electronics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 58, 2059–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, Y.; Winn, J.N.; Fan, S.; Chen, C.; Michel, J.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Thomas, E.L. A Dielectric Omnidirectional Reflector. Science 1998, 282, 1679–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; She, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, G.; Xiao, S. Angle-immune strong coupling between two defect modes in a defective photonic hypercrystal. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 186, 108842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Bi, D.; Qi, X.; Ren, M.; Wu, F. Angle-independent topological interface states in one-dimensional photonic crystal heterostructures containing hyperbolic metamaterials. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foresi, J.S.; Villeneuve, P.R.; Ferrera, J.; Thoen, E.R.; Steinmeyer, G.; Fan, S.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Kimerling, L.C.; Smith, H.I.; Ippen, E.P. Photonic-bandgap microcavities in optical waveguides. Nature 1997, 390, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deotare, P.B.; McCutcheon, M.W.; Frank, I.W.; Khan, M.; Loncar, M. High quality factor photonic crystal nanobeam cavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 121106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velha, P.; Picard, E.; Charvolin, T.; Hadji, E.; Rodier, J.; Lalanne, P.; Peyrade, D. Ultra-High Q/V Fabry-Perot microcavity on SOI substrate. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 16090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, G.; Xiong, M.; Dimopoulos, E.; Sakanas, A.; Semenova, E.; Yvind, K.; Yu, Y.; Mørk, J. Experimental demonstration of a nanobeam Fano laser. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ye, M.; Yu, Z.; Xue, W. Notch microwave photonic filter with narrow bandwidth and ultra-high all-optical tuning efficiency based on a silicon nanobeam cavity. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 5051–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Gan, X.; Han, G.; Liu, Y.; Hao, Y. Ultrahigh thermal-efficient all-optical silicon photonic crystal nanobeam cavity modulator with TPA-induced thermo-optic effect. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, H.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, H.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Y. Ultra-low-power consumption silicon electro-optic switch based on photonic crystal nanobeam cavity. npj Nanophoton. 2024, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Han, Z.; Tian, H. On-chip trapping and sorting of nanoparticles using a single slotted photonic crystal nanobeam cavity. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 11192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Dong, P.; Shi, Y. Suspended slotted photonic crystal cavities for high-sensitivity refractive index sensing. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 12272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, Q.; Deotare, P.B.; Loncar, M. Photonic crystal nanobeam cavity strongly coupled to the feeding waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 203102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Qiu, H.; Yu, H.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Yang, J. High-Q and high-order side-coupled air-mode nanobeam photonic crystal cavities in silicon. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2016, 28, 2121–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernice, W.H.P.; Xiong, C.; Schuck, C.; Tang, H.X. High-Q aluminum nitride photonic crystal nanobeam cavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 091105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Qiu, C.; Hu, T.; Qiu, H.Y.; Ge, F.F.; Jiang, X.Q.; Yang, J.Y. High- Q Photonic Crystal Cavity in a Single-Mode Silicon Ridge Waveguide. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2013, 30, 104204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Qiu, H.; Dai, T.; Cheng, R.; Lian, B.; Li, W.; Yu, H.; Yang, J. Ultracompact Channel Add-Drop Filter Based on Single Multimode Nanobeam Photonic Crystal Cavity. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, F.O.; Halimi, S.I.; Weiss, S.M. Efficient side-coupling to photonic crystal nanobeam cavities via state-space overlap. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2019, 36, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimi, S.I.; Hu, S.; Afzal, F.O.; Weiss, S.M. Realizing high transmission intensity in photonic crystal nanobeams using a side-coupling waveguide. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haus, H.A. Waves and Fields in Optoelectronics; Solid State Physical Electronics Series; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984; p. 402. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.; Hu, T.; Qiu, C.; Shen, A.; Qiu, H.; Wang, F.; Jiang, X.; Wang, M.; Yang, J. Ultracompact, Reflection-Free and High-Efficiency Channel Drop Filters Based on Photonic Crystal Nanobeam Cavities. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2013, 30, 034210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbonas, D.; Balčytis, A.; Vaškevičius, K.; Gabalis, M.; Petruškevičius, R. Air and dielectric bands photonic crystal microringresonator for refractive index sensing. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Fauchet, P.M. Slow-light dispersion in periodically patterned silicon microring resonators. Opt. Lett. 2011, 37, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldring, D.; Levy, U. Highly dispersive micro-ring resonator based on one dimensional photonic crystal waveguide design and analysis. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 3156–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; McClung, A.; Srinivasan, K. High-Q slow light and its localization in a photonic crystal microring. Nat. Photon. 2022, 16, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Qiu, H.; Cheng, R.; Chrostowski, L.; Yang, J. High-Q antisymmetric multimode nanobeam photonic crystal cavities in silicon waveguides. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 26196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Jeon, S.W.; Song, B.S.; Tanaka, Y.; Asano, T.; Noda, S. Analysis of Q-factors of structural imperfections in triangular cross-section nanobeam photonic crystal cavities. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2015, 32, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).