Roadmap for Exoplanet High-Contrast Imaging: Nulling Interferometry, Coronagraph, and Extreme Adaptive Optics

Abstract

1. Introduction

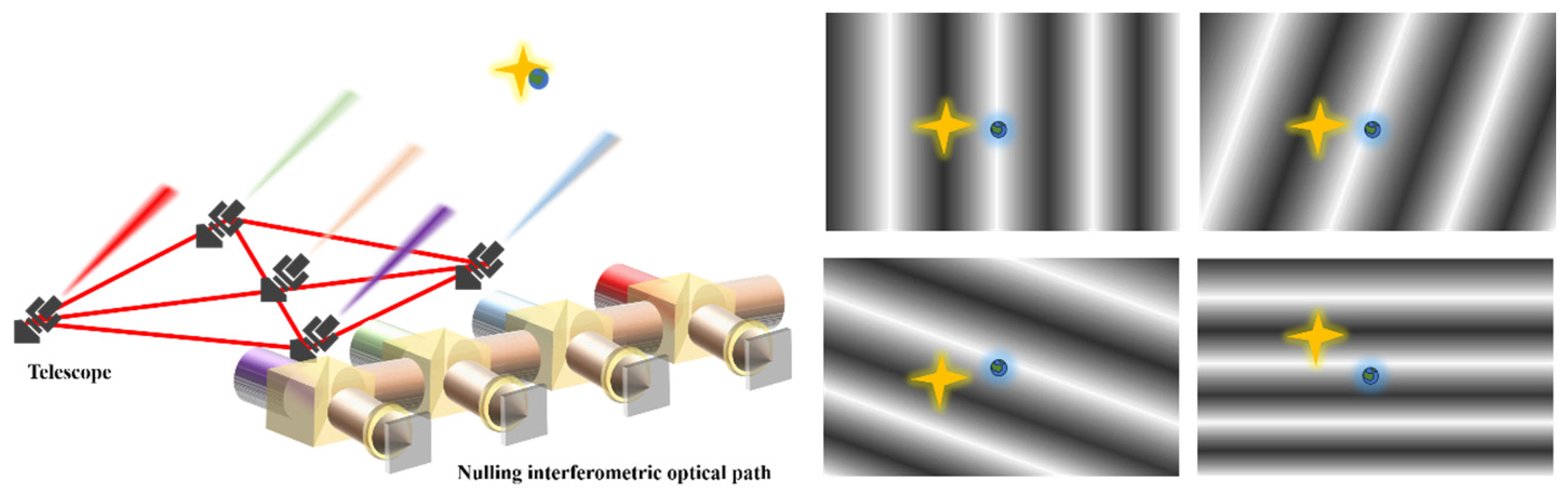

- Suppressing Stellar Light via Coherent Cancelation (Nulling Interferometry): The initial challenge was to selectively suppress the intense starlight while preserving the faint planetary signal. This motivated the concept of nulling interferometry, first proposed by Bracewell in 1978 [4]. By precisely controlling the phase difference (π-shift) between light beams collected by separated telescopes, destructive interference nullifies the on-axis starlight, creating a “dark fringe” where off-axis planetary light can constructively interfere. Early space mission concepts like DARWIN (ESA) and TPF-I (NASA) aimed to leverage this principle but faced technological hurdles [5]. Ground-based efforts, such as the OHANA project demonstrating fiber-linked interferometry on Mauna Kea and the Keck Interferometer Nuller, validated the concept but grappled with atmospheric turbulence and sensitivity limits [6]. The quest for higher stability, sensitivity, and resolution led to multi-telescope beam combiners like MIRC/MIRC-X (CHARA array) and breakthroughs in the mid-infrared with the LBTI (Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer) and its NIC (Nulling and Imaging Camera) [7]. The recent revolution in integrated photonics, exemplified by instruments like Dragonfly and GLINT, promises miniaturized, robust nulling interferometers [8]. The ultimate vision for space-based nulling is embodied in the LIFE (Large Interferometer For Exoplanets) mission concept, employing advanced “kernel-nulling” for unprecedented contrast in the mid-IR in the future [9].

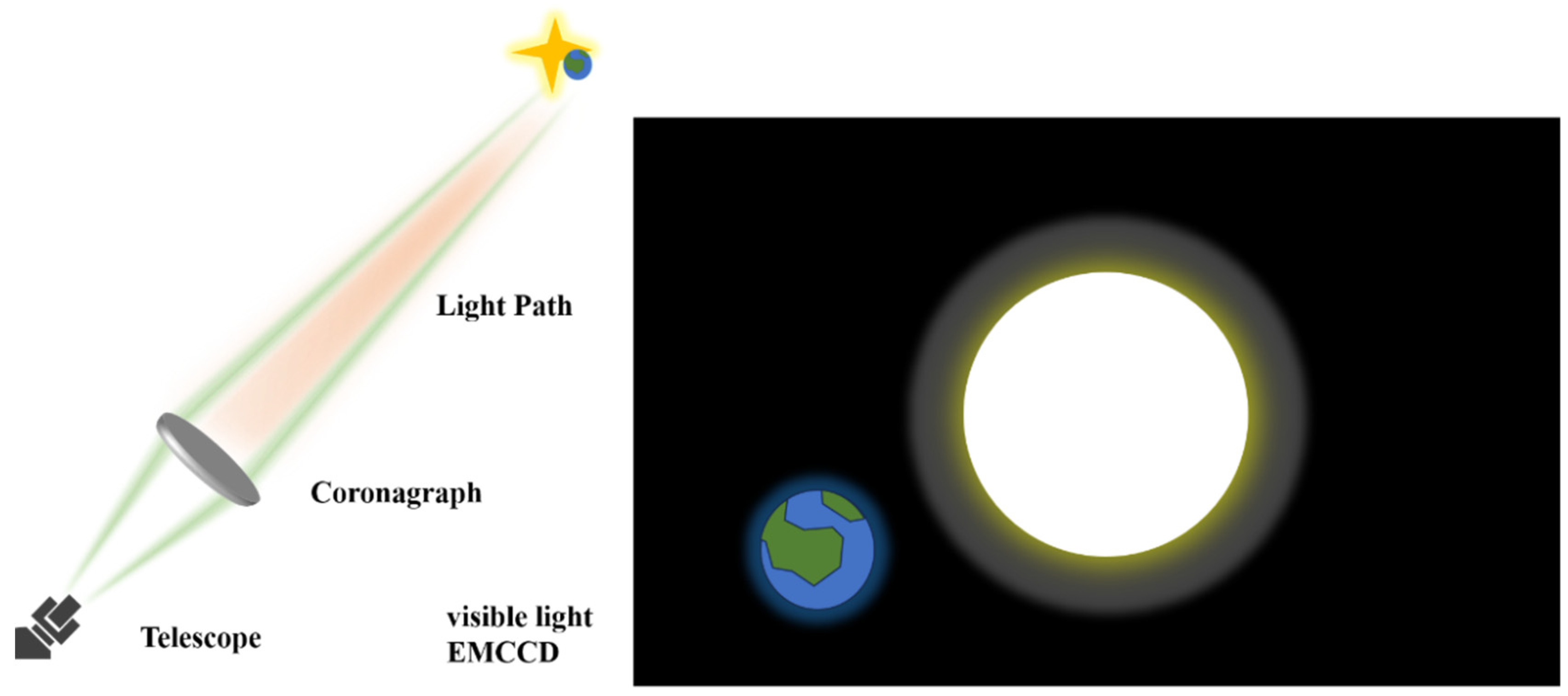

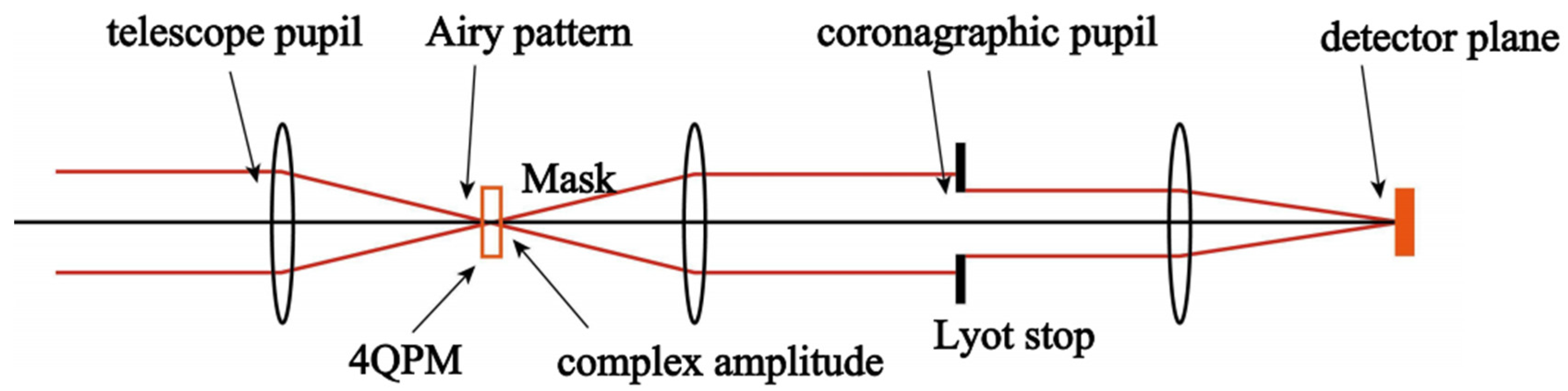

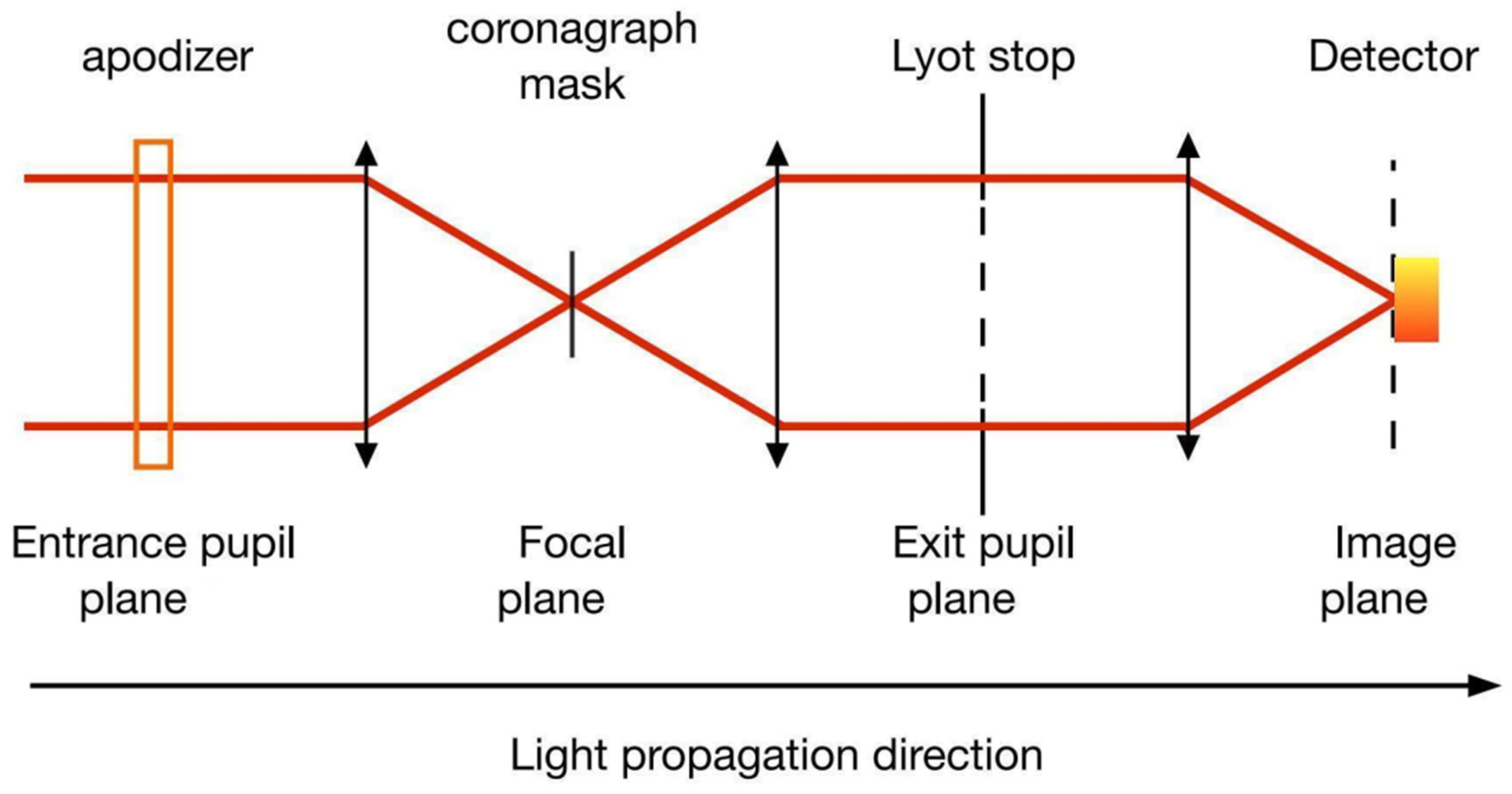

- Creating Localized Dark Regions via Diffraction Control (Coronagraphy): Complementing interferometry, coronagraphy tackles the contrast challenge by locally blocking or diffracting starlight within the telescope’s focal plane [10]. Early concepts involved external occulters, but their impractical scale for exoplanets (requiring massive structures tens of thousands of kilometers from the telescope) shifted focus to internal coronagraphs. The foundational Lyot coronagraph (1930s) used a focal plane mask and pupil stop. Subsequent innovations focused on mask design to improve performance: Band-Limited Masks (BLMC) optimized diffraction suppression [11]; phase masks (e.g., Four-Quadrant Phase Mask—4QPMC, Eight-Octant Phase Mask—EOPM, Optical Vortex Coronagraph—OVPMC) utilized destructive interference with higher theoretical contrast and smaller inner working angles (IWAs), demonstrated on instruments like Subaru’s HiCIAO/SCExAO [12]; and apodized pupil concepts (e.g., Classical Pupil Apodization—CPA, Apodized Pupil Lyot Coronagraph—APLC) modulated the pupil amplitude. A significant leap came with Phase-Induced Amplitude Apodization (PIAA), using aspheric optics to reshape the beam without significant light loss, later combined with complex masks as PIAACMC, a technology baselined for missions like WFIRST-CGI and crucial for ground-based systems like VLT-SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch) and Subaru-SCExAO [13].

- Enabling High-Fidelity Wavefront Control (Extreme Adaptive Optics—ExAO): Both nulling interferometry and coronagraphy are critically dependent on achieving near-perfect wavefront quality and stability. Atmospheric turbulence and static optical aberrations degrade performance. This necessity birthed ExAO, an advanced form of adaptive optics pushing correction fidelity to the extreme. Early conceptual work laid the groundwork. Key developments included: high-density deformable mirrors (DMs) with thousands of actuators (e.g., MEMS DMs for XAOPI concept); advanced wavefront sensors like the pyramid wavefront sensor (PWFS) and Asymmetric Pupil Fourier Wavefront Sensor (APF-WFS) [14]; sophisticated real-time control algorithms (e.g., Fourier transform methods, Multigrid Conjugate Gradient—MGCG) [15]; and techniques for Non-Common Path Aberration (NCPA) correction. Instruments like Subaru-SCExAO and MagAO-X integrate these technologies, providing the stable, high-Strehl-ratio (>0.9) point spread function (PSF) essential for modern coronagraphs and coherent beam combination in interferometry [16]. Innovations like Microwave Kinetic Inductance Detectors (MKIDs) integrated into MKID-PWFS promise further gains in sensitivity and multi-band wavefront sensing [17].

2. Existing High-Contrast Imaging Techniques

2.1. Nulling Interferometry

2.1.1. Early Concepts and Space Mission Proposals: Bracewell, DARWIN and TPF-I

2.1.2. Ground-Based Fiber Interferometric Array: OHANA Project

2.1.3. Traditional Bulk-Optics Interferometers: Keck Interferometer Nuller and Nulling Depth Formula

2.1.4. Multi-Telescope Infrared Interferometry: MIRC and MIRC-X

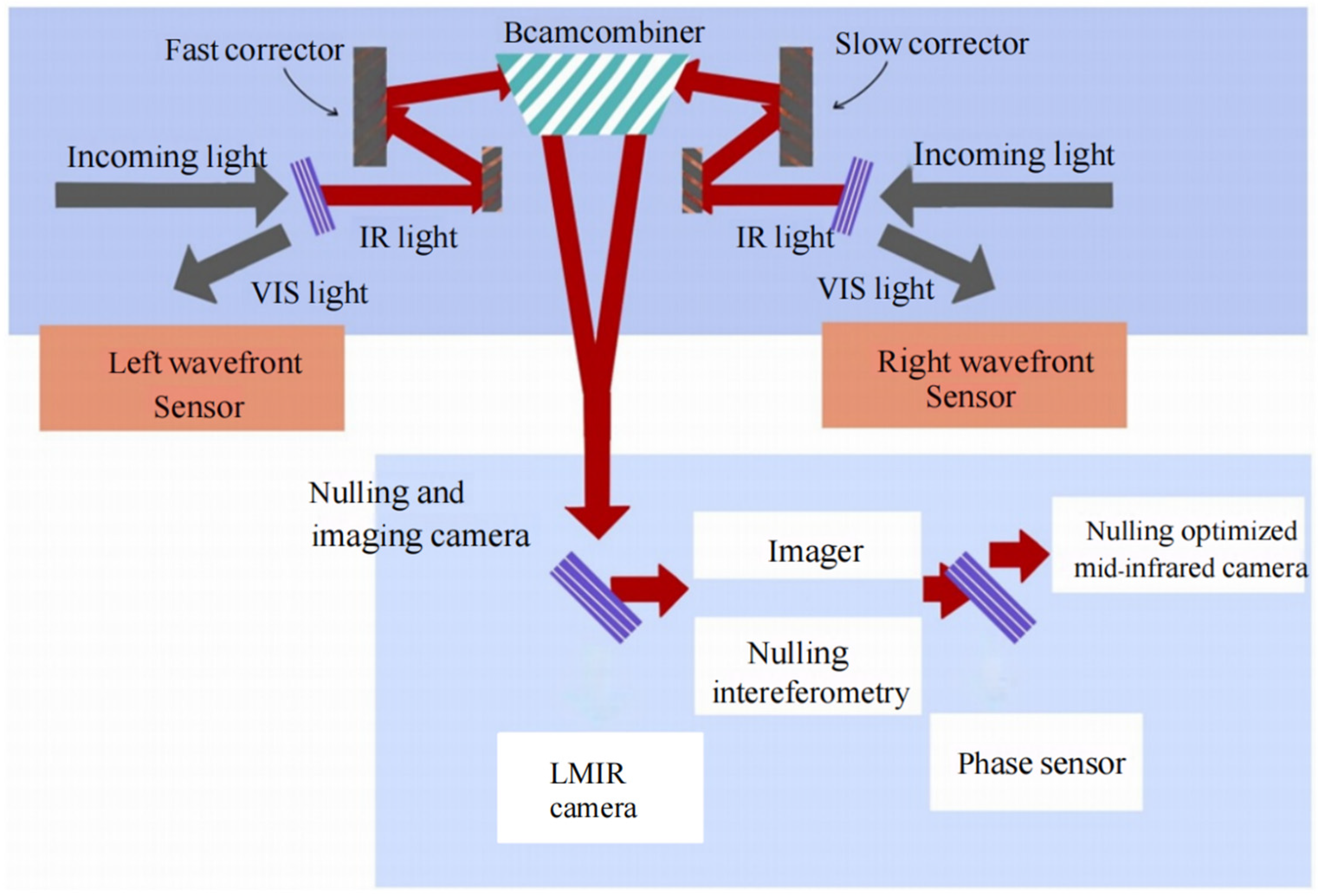

2.1.5. Breakthrough in Mid-Infrared: LBTI and NIC

2.1.6. Integrated Photonics Revolution: Dragonfly and GLINT

2.1.7. Future Directions: Kernel-Nulling and the LIFE Mission

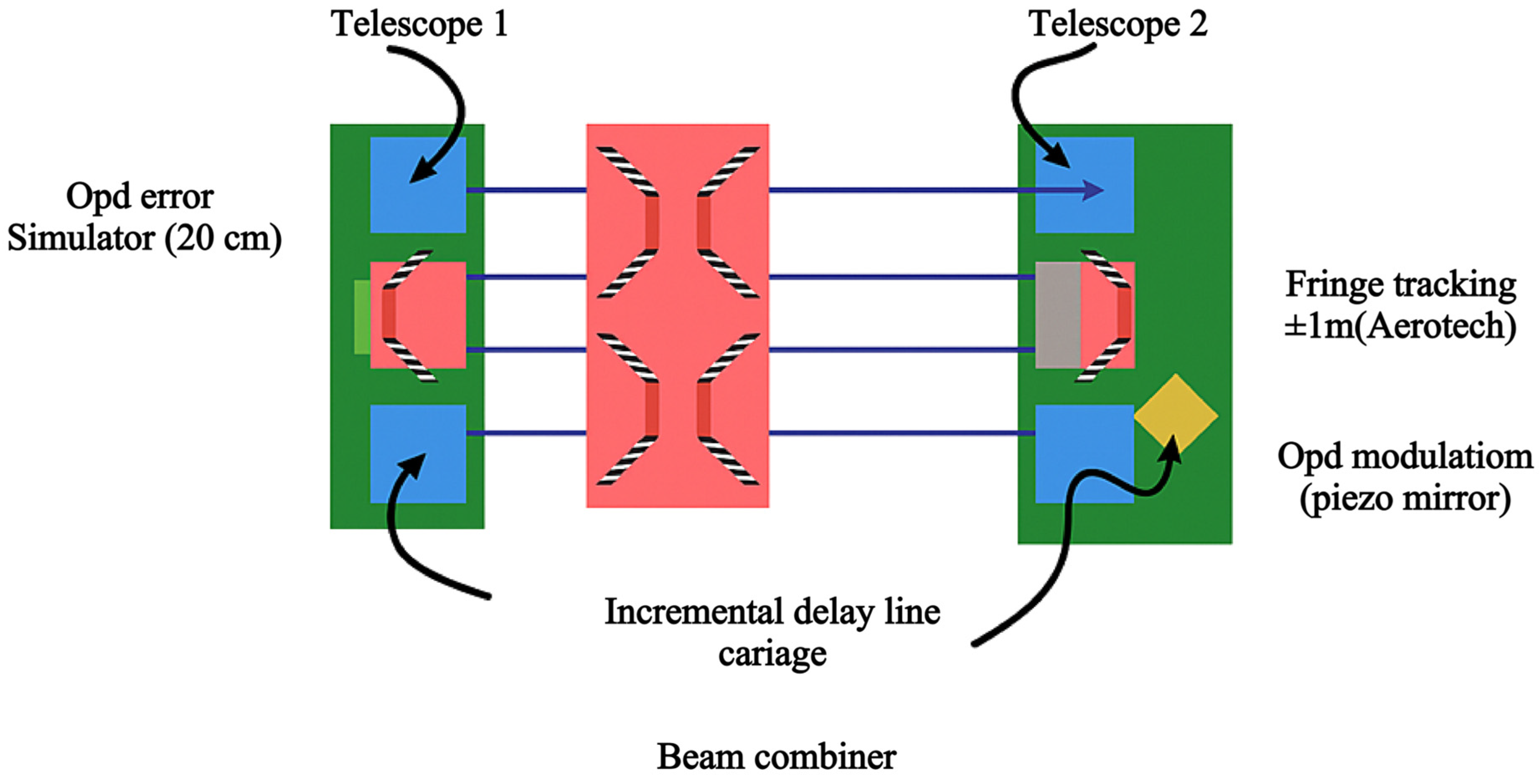

2.1.8. Dynamic Maintenance

2.1.9. Categorization

Spectral Dispersion

Color Difference Correction Type (Chromatic Aberration Control)

- Prime focus corrector design: The FMOS prime focus corrector is designed to optimize the image quality within the 0.9–1.8 µm wavelength range [51]. The corrector employs a three-element lens design, with all elements made from BSM51Y glass material to minimize chromatic and other optical aberrations.

- Plan-focal field: The corrector is designed with a plan-focal field to simplify the accurate focusing of the fiber tips and module installation. The plan-focal field also ensures that the main light rays are aligned with the fiber axis across the entire field of view, minimizing the efficiency losses caused by a mismatch between the beam and the fiber acceptance cone. The advantages of chromatic aberration correction are its relatively simple optical design and high adaptability.

- Using dispersion compensation elements such as prisms or gratings to guide light of different wavelengths to the correct paths.

- Optimizing optical design using achromatic lens groups to reduce the effects of chromatic aberration.

- Real-time wavefront correction using adaptive optical systems to monitor and correct wavefront distortions in real time, including chromatic aberration.

Polarization Control

- Polarization control: Ensures that the light waves entering the interferometer have consistent polarization states to minimize polarization-induced changes in interference signals.

- Polarization separation: In certain cases, it may be necessary to separate light waves with different polarization states for processing to eliminate the effects of polarization on specific measurement tasks.

- Polarization calibration: During calibration process of an interferometer, a polarimeter is used to measure and adjust the polarization state of the optical path to ensure the accuracy and stability of the interferogram.

Integrated Photonic Nulling Interferometry

2.1.10. Distinction Between Space-Borne and Ground-Based Implementations in Nulling Interferometry

2.2. Coronagraph

2.2.1. External Occultation Coronagraph

- Simplified optical system: No special telescope or adaptive optics systems are required; only a conventional telescope is required.

- Breakthrough in the diffraction-limited inner working angle: The size depends on the dimensions and position of the external shelter, and is not constrained by the optical system itself. The minimum theoretically detectable angular distance can reach 0.01″ (better than the diffraction limit λ/D ≈ 0.03″). However, unlike the external coronagraph, the stellar angular size is significantly smaller than that of the Sun (16 arcmin), leading to significantly increased technical challenges. For a 4 m aperture telescope, the diameter of the outer occulter must reach 50 m, and the distance from the telescope must be 80,000 km. The internal working angle of the coronagraph (generally within 0.5 arcs in the visible light band) is also significantly smaller than that of the solar coronagraph. The outer occulter must be carried by a spacecraft and operated in a very high orbit, and must remain synchronized with the telescope at all times, making implementation extremely challenging. Due to the above limitations, the inner-occultation coronagraph has emerged as the mainstream approach [58].

2.2.2. Internal Occultation Coronagraphs

The Interferometric Coronagraph

Lyot-Type Coronagraphs

- Band-Limited Mask Coronagraph (BLMC)

- b.

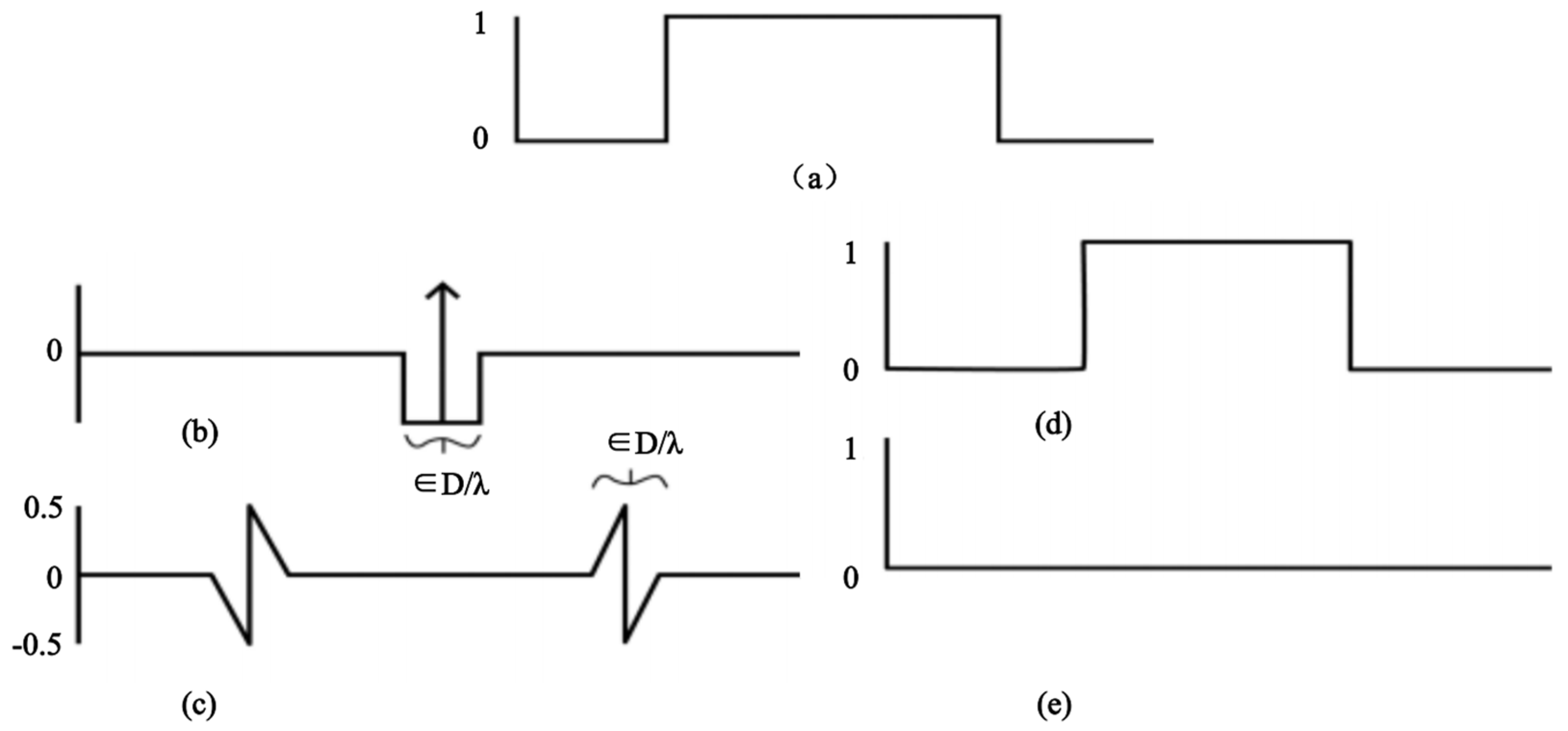

- Phase-type Coronagraphs

Pupil Apodization Coronagraphs

Phase-Induced Amplitude Apodization Coronagraph

2.2.3. Distinction Between Space-Borne and Ground-Based Implementations in Coronagraph

2.3. ExAO

2.3.1. Concept Proposal and Early Exploration: Angel, LLNL and UCSC

2.3.2. Algorithmic Breakthrough: Fast Wavefront Reconstruction

- Impulse response:

- Transfer function (math.):

2.3.3. Planet Imager Concept Design: XAOPI

2.3.4. Efficient Large-Scale Correction: MGCG Algorithm (Gilles)

2.3.5. Non-Common Path Error Correction: Differential Wavefront Sensing

2.3.6. System Integration Benchmark: Subaru SCExAO

2.3.7. Wavefront Sensing Innovation: APF-WFS (Martinache)

2.3.8. Advanced Detectors and Multi-Band Capability: MKID-PWFS

- Pyramidal Wavefront Sensor via the Split Approach

- b.

- Direct Segmented Piston Reconstructor (DSPR) Approach

2.3.9. Performance Verification and Scientific Output

2.3.10. ExAO: A Predominantly Ground-Based Enabling Technology

3. Development Trends

3.1. ExAO, Mutual Promotion Between Coronagraphs and Nulling Interferometry

3.1.1. ExAO to Enhance the Performance of Coronagraphs

3.1.2. Phase Assurance for ExAO Nulling Interferometry

3.2. Applications of Deep Learning

3.3. Integrated Photonics and the Application of Optical Neural Networks to Astronomical High-Contrast Scenes

3.3.1. Integrated Photonics

3.3.2. Optical Neural Networks

3.4. The Key Challenges That Are Expected to Arise in the Short and Long Term

3.4.1. Near-Term Horizon (~1–5 Years): Integration and Ground-Based Validation

- Unified Control Architectures: Develop and implement real-time control systems capable of orchestrating ExAO correction, coronagraph mask optimization, nulling phase control, and potential AI co-processing within a single, low-latency framework.

- Advanced NCPA Calibration and Suppression: Prioritize research into next-generation wavefront sensing (e.g., asymmetric pupil, modulated pyramid WFS) and techniques like PSF replication or differential optical path monitoring integrated directly into the science path for high-precision (<λ/100 RMS) static aberration control.

- Photonic Chip Prototyping and Validation: Accelerate the development, fabrication, and on-sky testing of more complex integrated photonic circuits for nulling (multi-baseline kernel-nulling chips) and beam combination, focusing on improving throughput, phase stability, and turbulence filtering capabilities.

- AI for Enhanced Operations: Deploy foundational deep learning models for predictive wavefront control (reducing latency), real-time speckle noise identification and subtraction in coronagraphic data, and optimizing observational strategies (target selection, exposure times).

- High-Fidelity System Modeling: Enhance end-to-end simulation tools to accurately model the coupled physics of turbulence, wavefront correction, coronagraphic diffraction, nulling coherence, and detector effects for design optimization and performance prediction.

3.4.2. Mid-Term Horizon (~5–15 Years): Scaling and Space Qualification

- ELT-Scale ExAO Systems: Drive advancements in high-density deformable mirrors (e.g., MEMS, piezo), advanced wavefront sensors (e.g., MKID-PWFS, LIFT), laser guide star systems, tomographic reconstruction algorithms, and real-time computing architectures capable of handling ELT complexity and data rates.

- Space Coronagraph and Nulling Technology: Mature technologies like PIAACMC, vector vortex coronagraphs, and integrated photonic nullers for space environments. Focus on thermal/mechanical stability, radiation hardening, and in-flight calibration capabilities. Demonstrate 10−10 contrast stability in testbeds and sub-orbital flights.

- Photonics and ONNs for Real-Time Control: Develop and integrate photonic co-processors and ONNs capable of performing wavefront reconstruction, nonlinear control, and speckle field manipulation at nanosecond speeds, overcoming electronic latency limitations.

- Precision Formation Flying and Interferometry: Advance metrology systems, propulsion, and control algorithms for nanometer-to-picometer level maintenance of baseline distances and optical path differences in distributed spacecraft systems (e.g., LIFE precursor missions).

- Advanced Biosignature Detection and Validation: Develop sophisticated spectral retrieval pipelines, incorporate context from planetary system architecture, and establish rigorous frameworks for quantifying false positive probabilities for potential biosignatures like O2-CH4 disequilibrium.

3.4.3. Long-Term Horizon (>15 Years): Earth-Analog Characterization

- Extreme Stability Platforms: Pioneer revolutionary spacecraft and optical bench designs incorporating active and passive isolation, advanced materials (e.g., zero-CTE composites), and nanometer-level metrology and control systems for unprecedented dynamic stability.

- Ultra-Sensitive, Multi-Band Detection: Develop next-generation detectors (beyond MKIDs) with high quantum efficiency, extremely low noise, photon-counting capability, and intrinsic energy resolution across UV to mid-IR wavelengths critical for biosignatures.

- Advanced Atmospheric Retrieval and Biosignature Assessment: Create coupled climate-chemistry-photochemical models and AI-powered retrieval tools capable of interpreting complex, low-SNR spectra within a full planetary context to assess habitability and the probability of life.

- Photonics and Quantum Sensing Integration: Fully realize the vision of photonic intelligent terminals by deeply integrating photonic circuits for light manipulation, optical neural networks for processing, and potentially quantum sensors for ultra-precise metrology into a unified, high-efficiency system.

- Large Mission Architectures and Funding Strategies: Conduct comprehensive system studies, technology maturation programs, and international collaborations to define and secure the path towards constructing and launching these ambitious observatories.

4. Summary

- Convergence: The deep integration of ExAO, coronagraphs, and nulling interferometry is transitioning from a promising concept to a necessity. Future systems will feature unified control architectures where ExAO not only corrects turbulence but also actively compensates for coronagraph-specific NCPA and maintains the sub-nanometer phase stability required for deep nulling over extended integrations. This synergistic approach addresses the core limitations of individual techniques, pushing achievable contrast closer to the theoretical limits demanded by exo-Earth characterization, as exemplified by the performance gains demonstrated in systems like VLT-SPHERE and envisioned for future missions like LIFE.

- Intelligence (Deep Learning): Deep learning represents a paradigm shift in how high-contrast imaging systems are designed and operated. Moving beyond traditional analytical models, AI techniques offer powerful solutions for critical bottlenecks: predicting atmospheric turbulence evolution for faster ExAO control, intelligently disentangling speckle noise from true planetary signals in coronagraphic data, optimizing observing strategies and fringe tracking for nulling interferometry, and even directly interpreting complex planetary spectra for biosignatures. This AI-driven approach promises orders-of-magnitude improvements in speed, sensitivity, and autonomy compared to conventional algorithms.

- Photonic Integration and Optical Neural Networks: Integrated photonics and optical neural networks offer a fundamental leap in system architecture and capability. Replacing bulk optics with photonic chips enables miniaturization, inherent stability, and novel functionalities like on-chip nulling (GLINT) or turbulence filtering. Optical neural networks, leveraging light-speed linear computation and multi-physical dimension processing, promise to overcome the fundamental real-time bottleneck of electronic systems for ExAO control and enable physical-layer noise suppression for coronagraphs at levels unattainable digitally. This convergence of photonics and AI aims to transition the entire high-contrast imaging chain from a sequential “sense-store-process” model to an integrated “sensing-computing” photonic intelligent terminal, operating at the ultimate speed limit—light itself. This represents a qualitative departure from the discrete, electronics-limited systems of today.

- Near-Term (~1–5 years): Focus on integrating and validating convergent systems on existing large telescopes, achieving 10−8 contrast, and prioritizing unified control, advanced NCPA suppression, photonic chip prototyping, and initial AI deployment.

- Mid-Term (~5–15 years): Scale convergent technologies to ELTs (10−9 contrast) and medium space missions, prioritizing ELT-scale ExAO, space coronagraph/nullers, photonic/ONN real-time control, precision formation flying, and advanced biosignature detection.

- Long-Term (>15 years): Deploy large space observatories (flagship coronagraphs or interferometric arrays) capable of 10−10 contrast and <0.1″ resolution to image and obtain spectra of Earth-like exoplanets, prioritizing extreme stability platforms, ultra-sensitive detectors, sophisticated biosignature assessment, and fully realized photonic intelligent terminals.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ExAO | Extreme Adaptive Optics |

| LIFE | Large Interferometer For Exoplanets |

| CCD | Charge-Coupled Device |

| MKID | Microwave Kinetic Inductance Detector |

| MGCG | Multi-Grid Conjugate Gradient |

| APF-WFS | Asymmetric Pupil Fourier Wavefront Sensor |

| PIAA | Phase-Induced Amplitude Apodization |

| PIAACMC | Phase-Induced Amplitude Apodization Complex Mask Coronagraph |

| APLC | Apodized Pupil Lyot Coronagraph |

| BLMC | Band-Limited Mask Coronagraph |

| 4QPMC | Four-Quadrant Phase Mask |

| EOPM | Eight-Octant Phase Mask |

| OVPMC | Optical Vortex Coronagraph |

| HDFS | Holographic Dispersed Fringe Sensor |

| GRIP | Generic Reduction for Interferometric Nulling |

| GMT | Giant Magellan Telescope |

| SCExAO | Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics |

| MagAO-X | Magellan Adaptive Optics eXtreme |

| CSST | Chinese Space Station Telescope |

| NCPA | Non-Common Path Aberrations |

| PSF | Point Spread Function |

| DM | Deformable Mirror |

| PWFS | Pyramid Wavefront Sensor |

| LGS | Laser Guide Star |

| AO | Adaptive Optics |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| ONN | Optical Neural Network |

References

- Rukdee, S. Instrumentation Prospects for Rocky Exoplanet Atmospheres Studies with High Resolution Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, H.R.; Baines, E.K.; Armstrong, J.T.; Restaino, S.R. Detecting Exoplanets and Characterizing Their Properties with Fringe Nulling. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VI, Austin, TX, USA, 10–12 June 2018; Mérand, A., Creech-Eakman, M.J., Tuthill, P.G., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; Volume 10701, p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, B.A. Exoplanet Detection and Characterization via Parallel Broadband Nulling Coronagraphy. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2016, 2, 011015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, J.R.R. Interferometry with the Large Binocular Telescope. In Proceedings of the Optical Telescopes of Today and Tomorrow, Landskrona/Hven, Sweden, 23–27 September 1996; Volume 2871, pp. 595–597. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, M.J.; Madden, S.; Rapp, L. Spatial Filtering for the Large Interferometer For Exoplanets (LIFE) Mission. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging IX, Yokohama, Japan, 16–21 June 2024; Sallum, S., Sanchez-Bermudez, J., Kammerer, J., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; Volume 13099, p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Woillez, J.M.; Perrin, G.S.; Guerin, J.; Lai, O.; Reynaud, F.; Wizinowich, P.L.; Neyman, C.R.; Le Mignant, D.; Roth, K.C.; White, J. OHANA Phase I: Adaptive Optics and Single-Mode Fiber Coupling. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VI, Glasgow, UK, 21–25 June 2004; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5491, pp. 1425–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Ertel, S.; Hinz, P.M.; Stone, J.M.; Vaz, A.; Montoya, O.M.; West, G.S.; Durney, O.; Grenz, P.; Spalding, E.A.; Leisenring, J.M.; et al. Overview and Prospects of the LBTI beyond the Completed HOSTS Survey. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VII, Online, 14–22 December 2020; Mérand, A., Sallum, S., Tuthill, P.G., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Martinod, M.-A.; Norris, B.; Gross, S.; Arriola, A.; Gretzinger, T.; Withford, M.J.; Lagadec, T.; Tuthill, P.G. Imaging Exoplanets with Nulling Interferometry Using Integrated-Photonics: The GLINT Project. In Proceedings of the Advances in Optical Astronomical Instrumentation, Melbourne, Australia, 8–12 December 2019; Ellis, S.C., d’Orgeville, C., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Glauser, A.M.; Quanz, S.P.; Hansen, J.; Dannert, F.; Ireland, M.J.; Linz, H.; Absil, O.; Alei, E.; Angerhausen, D.; Birbacher, T.; et al. The Large Interferometer For Exoplanets (LIFE): A Space Mission for Mid-Infrared Nulling Interferometry. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging IX, Yokohama, Japan, 16–22 June 2024; Sallum, S., Sanchez-Bermudez, J., Kammerer, J., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Potier, A.; Ruane, G.; Stark, C.; Chen, P.; Chopra, A.; Dewell, L.; Juanola-Parramon, R.; Nordt, A.; Pueyo, L.; Redding, D.; et al. Adaptive Optics Performance of a Simulated Coronagraph Instrument on a Large, Segmented Space Telescope in Steady State. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2022, 8, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.H.; Rogers, E.T.; Zheludev, N.I. Achromatic Super-Oscillatory Lenses with Sub-Wavelength Focusing. Light Sci. Appl. 2017, 6, e17036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, T.M.; Guyon, O.; Lozi, J.; Sahoo, A.; Vievard, S.; Deo, V.; Chilcote, J.; Groff, T.; Brandt, T.; Lawson, K.; et al. On-Sky Performance and Recent Results from the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics System. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems VII, Online, 14–22 December 2020; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Vernet, E., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sallard, C.; Martinez, P.; Spang, A.; Marcotto, A.; Beaulieu, M.; Gouvret, C.; Dejonghe, J. Phase-Induced Amplitude Apodization Complex Mask Coronagraph (PIAACMC) without PIAA: Redesigning a Phase-Induced Amplitude Apodization to a Conventional Pupil Amplitude Apodization. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems IX, Yokohama, Japan, 16–21 June 2024; Schmidt, D., Vernet, E., Jackson, K.J., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Shatokhina, I.; Hutterer, V.; Ramlau, R. Review on Methods for Wavefront Reconstruction from Pyramid Wavefront Sensor Data. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2020, 6, 010901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, L. Sparse Minimum-Variance Open-Loop Reconstructors for Extreme Adaptive Optics: Order N Multigrid versus Preordered Cholesky Factorization. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optical System Technologies II, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–6 August 2003; Tyson, R.K., Lloyd-Hart, M., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 5169, pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Madurowicz, A.; Macintosh, B.; Chilcote, J.; Perrin, M.; Poyneer, L.; Pueyo, L.; Ruffio, J.-B.; Bailey, V.P.; Barman, T.; Bulger, J.; et al. Asymmetries in Adaptive Optics Point Spread Functions. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2019, 5, 049003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szypryt, P.; Bennett, D.A.; Fogarty Florang, I.; Fowler, J.W.; Giachero, A.; Hummatov, R.; Lita, A.E.; Mates, J.A.B.; Nam, S.W.; O’Neil, G.C.; et al. Kinetic Inductance Current Sensor for Visible to Near-Infrared Wavelength Transition-Edge Sensor Readout. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, R.; Haffert, S.Y.; Radhakrishnan, V.M.; Keller, C.U. Self-Optimizing Adaptive Optics Control with Reinforcement Learning for High-Contrast Imaging. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2021, 7, 039002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, T.D.; McLean, I.S. (Eds.) Planets, Stars and Stellar Systems: Volume 1: Telescopes and Instrumentation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 978-94-007-5620-5. [Google Scholar]

- MacPhie, R.H.; Bracewell, R.N. An Orbiting Infrared Interferometer to Search For Nonsolar Planets. In Proceedings of the Instrumentation in Astronomy III, Tucson, AZ, USA, 29 January–1 February 1979; Crawford, D.L., Ed.; American Astronomical Society: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1979; Volume 172, pp. 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Gondoin, P.; Absil, O.; Fridlund, M.; Erd, C.; Glindemann, A.; Koehler, B.; Wilhelm, R.; Karlsson, A.; Labadie, L.; Mann, I.; et al. The Darwin Ground-Based European Nulling Interferometry Experiment (GENIE). In Proceedings of the Toward Other Earths: Future Directions in the Search for Extrasolar Terrestrial Planets, Glasgow, UK, 21–25 June 2004; Penny, A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5491, pp. 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, J.K.; Babtiwale, V.; Bartos, R.; Brown, K.; Gappinger, R.; Loya, F.; MacDonald, D.; Martin, S.; Negron, J.; Truong, T.; et al. Mid-IR Interferometric Nulling for TPF. In Proceedings of the New Frontiers in Stellar Interferometry, Glasgow, UK, 14–18 June 2004; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5491, pp. 862–871. [Google Scholar]

- Bély, P.-Y.; Laurance, R.J.; Volonte, S.; Greenaway, A.; Haniff, C.; Lattanzi, M.; Mariotti, J.-M.; Noordam, J.E.; Vakili, F. Kilometric Baseline Space Interferometry. In Proceedings of the Targets for Space-Based Interferometry, Brussels, Belgium, 16–18 December 1992; Bély, P.-Y., Breckinridge, J.B., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1993; Volume 1947, pp. 164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, G.; Lai, O.; Lena, P. The Optical Hawaiian Array for Nano-Radian Astronomy. In Proceedings of the Advanced Technology Optical/IR Telescopes VI, Kona, HI, USA, 20–27 March 1998; Stepp, L.M., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1998; Volume 3352, pp. 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woillez, J.M.; Sol, H.; Perrin, G.S.; Lai, O. Tomography of Active Galactic Nuclei Broad Line Region: A Science Case for next-Generation Extremely Long Baseline Optical Interferometry. In Proceedings of the New Frontiers in Stellar Interferometry, Glasgow, UK, 14–18 June 2004; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5491, pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, G.S.; Lai, O.; Woillez, J.; Guerin, J.; Reynaud, F.; Ridgway, S.T.; Lena, P.J.; Wizinowich, P.L.; Tokunaga, A.T.; Nishikawa, J.; et al. OHANA Phase II: A Prototype Demonstrator of Fiber-Linked Interferometry between Very Large Telescopes. In Proceedings of the Interferometry for Optical Astronomy II, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 22–28 August 2002; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 4838, pp. 1290–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Kotani, T.; Perrin, G.S.; Woillez, J.M.; Guerin, J.; Maze, G. K Band Fibers for the OHANA Project. In Proceedings of the New Frontiers in Stellar Interferometry, Glasgow, UK, 14–18 June 2004; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5491, pp. 647–654. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway, S.T.; Perrin, G.S.; Woillez, J.; Guerin, J.; Lai, O. Optical Delay for OHANA. In Proceedings of the Interferometry for Optical Astronomy II, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 22–28 August 2002; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 4838, pp. 1310–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Malbet, F. Young Stellar Objects Science with Interferometry. In Proceedings of the Interferometry for Optical Astronomy II, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 22–28 August 2002; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 4838, pp. 554–563. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, O.; Ridgway, S.T.; Lena, P.J.; Perrin, G.S.; Fahlman, G.; Adamson, A.J.; Tokunaga, A.T.; Nishikawa, J.; Wizinowich, P.L.; Rigaut, F.J. OHANA Phase III: Scientific Operation of an 800-Meter Mauna Kea Interferometer. In Proceedings of the Interferometry for Optical Astronomy II, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 22–28 August 2002; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 4838, pp. 1296–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, G.S.; Lai, O.; Woillez, J.M.; Guerin, J.; Kotani, T.; Vergnole, S.; Adamson, A.J.; Ftaclas, C.; Guyon, O.; Lena, P.J.; et al. OHANA. In Proceedings of the New Frontiers in Stellar Interferometry, Glasgow, UK, 14–18 June 2004; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5491, pp. 391–401. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Monnier, J.D.; Ten Brummelaar, T.; Pedretti, E.; Thureau, N.D. Exoplanet Studies with CHARA-MIRC. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry, Marseille, France, 23–27 June 2008; Schöller, M., Danchi, W.C., Delplancke, F., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2008; Volume 7013, p. 70131K. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Monnier, J.D.; Che, X.; Ten Brummelaar, T.; Pedretti, E.; Thureau, N.D. MIRC Closure Phase Studies for High Precision Measurements. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry II, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 June–2 July 2010; Danchi, W.C., Delplancke, F., Rajagopal, J.K., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; Volume 7734, p. 77341A. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B.F.; Retter, A.; Eisner, J.A.; Thompson, R.R.; Muterspaugh, M.W. Interferometric Observations of Explosive Variables: V838 Mon, Nova Aql 2005, and RS Oph. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry, Orlando, FL, USA, 24–31 May 2006; Monnier, J.D., Schöller, M., Danchi, W.C., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 6268, p. 62681K. [Google Scholar]

- Stencel, R.E. Interferometric Studies of Disk-Eclipsed Binary Star Systems. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VI, Edinburgh, UK, 26 June–1 July 2016; Malbet, F., Creech-Eakman, M.J., Tuthill, P.G., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; Volume 9907, p. 990717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anugu, N.; Monnier, J.D.; Kraus, S.; Ennis, J.; Setterholm, B.; Le Bouquin, J.-B.; Lanthermann, C.; Davies, C.; Ten Brummelaar, T.; Haidar, M.; et al. MIRC-X/CHARA: Sensitivity Improvements with an Ultra-Low Noise SAPHIRA Detector. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VI, Austin, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; Mérand, A., Creech-Eakman, M.J., Tuthill, P.G., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Anugu, N.; Le Bouquin, J.-B.; Monnier, J.D.; Kraus, S.; Schaefer, G.H.; Setterholm, B.R.; Davies, C.L.; Gardner, T.; Labdon, A.; Lanthermann, C.; et al. CHARA/MIRC-X: A High-Sensitive Six Telescope Interferometric Imager Concept, Commissioning and Early Science. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VII, Online, 14–22 December 2020; Mérand, A., Sallum, S., Tuthill, P.G., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Setterholm, B.R.; Monnier, J.D.; Le Bouquin, J.-B.; Anugu, N.; Labdon, A.; Ennis, J.; Johnson, K.J.; Kraus, S.; Ten Brummelaar, T.A. MIRC-X Polarinterferometry at CHARA. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VII, Online, 14–22 December 2020; Mérand, A., Sallum, S., Tuthill, P.G., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, P.M.; Solheid, E.; Durney, O.; Hoffmann, W.F. NIC: LBTI’s Nulling and Imaging Camera. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry, Marseille, France, 23–27 June 2008; Schöller, M., Danchi, W.C., Delplancke, F., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2008; Volume 7013, p. 701339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hinz, P.; Durney, O.; Connors, T.; Montoya, M.; Schwab, C. Testing and Alignment of the LBTI. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry II, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 June–2 July 2010; Danchi, W.C., Delplancke, F., Rajagopal, J.K., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; Volume 7734, p. 77341W. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinod, M.-A.; Norris, B.; Tuthill, P.; Lagadec, T.; Jovanovic, N.; Cvetojevic, N.; Gross, S.; Arriola, A.; Gretzinger, T.; Withford, M.J.; et al. Scalable Photonic-Based Nulling Interferometry with the Dispersed Multi-Baseline GLINT Instrument. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, N.; Tuthill, P.G.; Norris, B.; Gross, S.; Stewart, P.; Charles, N.; Lacour, S.; Lawrence, J.; Robertson, G.; Fuerbach, A.; et al. Progress and Challenges with the Dragonfly Instrument; an Integrated Photonic Pupil-Remapping Interferometer. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry III, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1–6 July 2012; Delplancke, F., Rajagopal, J.K., Malbet, F., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2012; Volume 8445, p. 844505. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding, E.A.; Arcadi, E.; Douglas, G.; Gross, S.; Guyon, O.; Martinod, M.-A.; Norris, B.; Rossini-Bryson, S.A.; Taras, A.; Tuthill, P.G.; et al. The GLINT Nulling Interferometer: Improving Nulls for High-Contrast Imaging. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging IX, Yokohama, Japan, 16–22 June 2024; Sallum, S., Sanchez-Bermudez, J., Kammerer, J., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Errmann, R.; Minardi, S.; Labadie, L.; Dreisow, F.; Nolte, S.; Pertsch, T. Integrated Optics Interferometric Four Telescopes Nuller. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging V, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 June 2014; Rajagopal, J.K., Creech-Eakman, M.J., Malbet, F., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9146, p. 914626. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass, G.; Klinner-Teo, T.D.M.; Arcadi, E.; Spalding, E.A.; Withford, M.J.; Martinod, M.-A.; Tuthill, P.G.; Norris, B.R.M.; Guyon, O.; Gross, S. Ultrafast Laser Inscription of Achromatic Phase Shifters for the GLINT Integrated Nulling Interferometer. In Proceedings of the Advances in Optical and Mechanical Technologies for Telescopes and Instrumentation VI, Yokohama, Japan, 16–22 June 2024; Navarro, R., Jedamzik, R., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Martinod, M.-A.; Deyi Maria Klinner-teo, T.; Tuthill, P.G.; Gross, S.; Arcadi, E.; Douglass, G.; Webb, J.; Norris, B.R.M.; Guyon, O.; Lozi, J.; et al. Achromatic Nulling Interferometry and Fringe Tracking with 3D-Photonic Tricouplers with GLINT. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VIII, Montréal, QC, Canada, 17–22 July 2022; Mérand, A., Sallum, S., Sanchez-Bermudez, J., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kenchington Goldsmith, H.-D.; Ireland, M.J.; Martinache, F.; Cvetojevic, N.; Madden, S.J. Active Phase Change for a Kernel Nulling Interferometry. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VII, Online, 14–22 December 2020; Mérand, A., Sallum, S., Tuthill, P.G., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Vanasse, G.A.; Esplin, R.W.; Huppi, R.J. Selective Modulation Interferometric Spectrometer (SIMS) Technique Applied To Background Suppression. Opt. Eng. 1979, 18, 184403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Foriel, V.; Martinache, F.; Mary, D. Tunable Kernel-Nulling Interferometry for Direct Exoplanet Detection. In Proceedings of the Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2024: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave, Yokohama, Japan, 16–22 June 2024; Coyle, L.E., Perrin, M.D., Matsuura, S., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 158. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lau, K.H.; Breckenridge, W.G.; Nerheim, N.M.; Redding, D.C. Active Figure Maintenance Control Using an Optical Truss Laser Metrology System for a Space-Based Far-IR Segmented Telescope. In Proceedings of the Cryogenic Optical Systems and Instruments V, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–24 July 1992; Breakwell, J.V., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1992; Volume 1690, pp. 60–72. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tamura, N.; Takato, N.; Iwamuro, F.; Akiyama, M.; Kimura, M.; Tait, P.; Dalton, G.B.; Murray, G.J.; Smedley, S.; Maihara, T.; et al. Subaru FMOS Now and Future. In Proceedings of the Ground-Based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy IV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1–6 July 2012; McLean, I.S., Ramsay, S.K., Takami, H., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2012; Volume 8446, p. 84460M. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Setterholm, B.R.; Monnier, J.D.; Le Bouquin, J.-B.; Anugu, N.; Ennis, J.; Jocou, L.; Ibrahim, N.; Kraus, S.; Anderson, M.D.; Chhabra, S.; et al. MYSTIC: A High Angular Resolution K-Band Imager at CHARA. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2023, 9, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallement, M.; Huby, E.; Lacour, S.; Martin, G.; Barjot, K.; Perrin, G.; Rouan, D.; Lapeyrere, V.; Vievard, S.; Guyon, O.; et al. Photonic Beam-Combiner for Visible Interferometry with Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics/Fibered Imager for a Single Telescope: Laboratory Characterization and Design Optimization. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2023, 9, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondoin, P.A.; Absil, O.; Den Hartog, R.H.; Wilhelm, R.C.; Gitton, P.B.; d’Arcio, L.L.A.; Fabry, P.; Puech, F.; Fridlund, M.C.; Schoeller, M.; et al. Darwin-GENIE: A Nulling Instrument at the VLTI. In Proceedings of the New Frontiers in Stellar Interferometry, Glasgow, UK, 14–18 June 2004; Traub, W.A., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5491, pp. 775–784. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. Research on the Diffraction Properties of Phase Induced Amplitude Apodization Coronagraph. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics, Changchun, China, June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Belikov, R.; Stark, C.C.; Siegler, N.; Por, E.H.; Mennesson, B.; Redmond, S.F.; Chen, P.; Fogarty, K.W.; Guyon, O.; Juanola-parramon, R.; et al. Coronagraph Design Survey for Future Exoplanet Direct Imaging Space Missions. In Proceedings of the Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2024: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave, Yokohama, Japan, 16–22 June 2024; Coyle, L.E., Perrin, M.D., Matsuura, S., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Aime, C.J.; Theys, C.; Prunet, S.; Ferrari, A. A Comparison of Solar and Stellar Coronagraphs That Make Use of External Occulters. In Proceedings of the Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2024: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave, Yokohama, Japan, 16–22 June 2024; Coyle, L.E., Perrin, M.D., Matsuura, S., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Venet, M.; Bazin, C.; Koutchmy, S.; Lamy, P. Stray Light Rejection in Giant Externally-Occulted Solar Coronagraphs: Experimental Developments. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Space Optics—ICSO 2010, Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–8 October 2010; Kadowaki, N., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, R.; Zhao, H.; Li, C.; Fan, X.; Yu, C. Joint Optimization of Apodizer and Lyot Stop for Coronagraph with Four-Quadrant Phase Mask. In Proceedings of the AOPC 2019: Space Optics, Telescopes, and Instrumentation, Beijing, China, 7–9 July 2019; Xue, S., Zhang, X., Zhang, Z., Nardell, C.A., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2019; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pluzhnik, E.; Guyon, O.; Warren, M.; Ridgway, S.T.; Woodruff, R.A. PIAA Coronagraph Design: System Optimization and First Optics Testing. In Proceedings of the Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2006: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave, Orlando, FL, USA, 24–31 May 2006; Mather, J.C., MacEwen, H.A., De Graauw, M.W.M., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 6265, p. 62653S. [Google Scholar]

- Aime, C.; Soummer, R. Multiple-Stage Apodized Pupil Lyot Coronagraph for High-Contrast Imaging. In Proceedings of the Advancements in Adaptive Optics, Glasgow, UK, 21–25 June 2004; Bonaccini, D., Ellerbroek, B.L., Ragazzoni, R., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5490, pp. 456–463. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchner, M.J.; Traub, W.A. A Coronagraph with a Band-Limited Mask for Finding Terrestrial Planets. In Proceedings of the UV, Optical, and IR Space Telescopes and Instruments, Munich, Germany, 27–31 March 2000; Bely, P.Y., Breckinridge, J.B., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2000; Volume 4013, pp. 689–699. [Google Scholar]

- Rouan, D.; Riaud, P.; Boccaletti, A.; Clénet, Y.; Labeyrie, A. The Four-Quadrant Phase-Mask Coronagraph. I. Principle. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2000, 112, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Ruane, G.; Llop-Sayson, J.; Betrou-Cantou, A.; Potier, A.; Riggs, A.J.E.; Serabyn, E.; Mawet, D. Laboratory Demonstration of the Wrapped Staircase Scalar Vortex Coronagraph. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2023, 9, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Cao, Q.; Teng, D.; Wang, K. Flat-Top Sinusoidal Phase Mask Coronagraph. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2017, 54, 051102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, N.T.; Eldorado Riggs, A.J.; Jeremy Kasdin, N.; Carlotti, A.; Vanderbei, R.J. Shaped Pupil Lyot Coronagraphs: High-Contrast Solutions for Restricted Focal Planes. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2016, 2, 011012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, O.; Pluzhnik, E.A.; Ridgway, S.; Woodruff, R.A. Imaging Extrasolar Terrestrial Planets from Space with a PIAA Coronagraph. In Proceedings of the Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2006: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave, Orlando, FL, USA, 24–31 May 2006; Mather, J.C., MacEwen, H.A., De Graauw, M.W.M., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 6265, p. 62651F. [Google Scholar]

- Kasdin, N.J.; Vanderbei, R.J.; Spergel, D.N.; Littman, M.G. Optimal Shaped Pupil Coronagraphs for Extrasolar Planet Finding. In Proceedings of the Instrument Design and Performance for Optical/Infrared Ground-Based Telescopes, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 22–28 August 2002; Iye, M., Moorwood, A.F.M., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 4841, pp. 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, B.; Guyon, O.; Belikov, R.; Wilson, D.; Muller, R.; Sidick, E.; Balasubramanian, B.; Krist, J.; Poberezhskiy, I.; Tang, H. Phase-Induced Amplitude Apodization Complex Mask Coronagraph Mask Fabrication, Characterization, and Modeling for WFIRST-AFTA. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2016, 2, 011014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, M.; Golota, T.; Olivier, G.; Dinkins, M.; Oya, S.; Colley, S.; Eldred, M.; Watanabe, M.; Itoh, M.; Saito, Y.; et al. Implementation of Modal Optimization System of Subaru-188 Adaptive Optics. In Proceedings of the Advancements in Adaptive Optics, Orlando, FL, USA, 24–31 May 2006; Bonaccini Calia, D., Ellerbroek, B.L., Ragazzoni, R., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 6272, p. 62725G. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon, O.; Martinache, F.; Belikov, R.; Soummer, R.; Pluzhnik, M.P. High Performance PIAA Coronagraphy with Complex Amplitude Focal Plane Masks. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2010, 190, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Kern, B.D.; Marx, D.S.; Patterson, K.; Mejia Prada, C.; Seo, B.-J.; Shelton, J.C.; Shields, J.; Tang, H.; Truong, T.; et al. WFIRST Low Order Wavefront Sensing and Control Dynamic Testbed Performance under the Flight like Photon Flux. In Proceedings of the Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2018: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave, Austin, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; MacEwen, H.A., Lystrup, M., Fazio, G.G., Batalha, N., Tong, E.C., Siegler, N., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Bedrosian, G.; Noecker, C.; Au, M.; Creager, B.; Nachtigal, J.; Cardines, J.; Monacelli, B.; Brereton, S.; Kempenaar, J.; Rupp, J. Roman Coronagraph Instrument Integration and Test, Part 1: Planning and Execution of Assembly and Integration. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2025, 11, 031506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debes, J.H.; Ren, B.; Schneider, G. Pushing the Limits of the Coronagraphic Occulters on Hubble Space Telescope/Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2019, 5, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigan, A.; Beuzit, J.-L.; Dohlen, K.; Mouillet, D.; Otten, G.; Muslimov, E.; Philipps, M.; Dorn, R.; Kasper, M.; Baraffe, I.; et al. Bringing High-Spectral Resolution to VLT/SPHERE with a Fiber Coupling to VLT/CRIRES+. In Proceedings of the Ground-Based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy VII, Austin, TX, USA, 10–14 June 2018; Takami, H., Evans, C.J., Simard, L., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan, A.; Makidon, R.B.; Soummer, R.; Macintosh, B.A.; Troy, M.; Chanan, G.A.; Lloyd, J.P.; Perrin, M.D.; Graham, J.R.; Poyneer, L.; et al. Coronagraph Design for an Extreme Adaptive Optics System with Spatially Filtered Wavefront Sensing on Segmented Telescopes. In Proceedings of the Advancements in Adaptive Optics, Glasgow, UK, 21–25 June 2004; Bonaccini, D., Ellerbroek, B.L., Ragazzoni, R., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5490, pp. 535–544. [Google Scholar]

- Lumbres, J.R. Extreme Wavefront Control for Ground and Space Observatories. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Serabyn, E.; Wallace, J.K.; Troy, M.; Mennesson, B.; Haguenauer, P.; Gappinger, R.O.; Bloemhof, E.E. Extreme Adaptive Optics Using an Off-Axis Subaperture on a Ground-Based Telescope. In Proceedings of the Advancements in Adaptive Optics, Orlando, FL, USA, 24–31 May 2006; Bonaccini Calia, D., Ellerbroek, B.L., Ragazzoni, R., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 6272, p. 62722W. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, J.K.; Green, J.J.; Shao, M.; Troy, M.; Lloyd, J.P.; Macintosh, B. Science Camera Calibration for Extreme Adaptive Optics. In Proceedings of the Advancements in Adaptive Optics, Glasgow, UK, 21–25 June 2004; Bonaccini, D., Ellerbroek, B.L., Ragazzoni, R., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5490, pp. 370–377. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz, L.H. Development of a Three-Sided Pyramid Wavefront Sensor for Astronomical Adaptive Optics. Ph.D. Thesis, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, J.R.P. Ground-Based Imaging of Extrasolar Planets Using Adaptive Optics. Nature 1994, 368, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, B.J.; Gavel, D.T. Astronomy Applications of Adaptive Optics at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. In Proceedings of the Advances in Mirror Technology for Telescopes and Other Optical Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 4–6 August 2003; Saito, T.T., Lane, M.A., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 5178, pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gavel, D. Adaptive Optics at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. In Proceedings of the Advanced Wavefront Control: Methods, Devices, and Applications II, San Diego, CA, USA, 6–7 August 2004; Gonglewski, J.D., Vorontsov, M.A., Gruneisen, M.T., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5553, pp. 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Poyneer, L.A.; Macintosh, B.A. Wavefront Control for Extreme Adaptive Optics. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optical System Technologies II, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–6 August 2003; Tyson, R.K., Lloyd-Hart, M., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 5169, pp. 190–201. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh, B.A.; Bauman, B.; Wilhelmsen Evans, J.; Graham, J.R.; Lockwood, C.; Poyneer, L.; Dillon, D.; Gavel, D.T.; Green, J.J.; Lloyd, J.P.; et al. eXtreme Adaptive Optics Planet Imager: Overview and Status. In Proceedings of the Advancements in Adaptive Optics, Glasgow, UK, 21–25 June 2004; Bonaccini, D., Ellerbroek, B.L., Ragazzoni, R., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5490, pp. 359–369. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh, B.A.; Graham, J.; Poyneer, L.; Sommargren, G.; Wilhelmsen, J.; Gavel, D.; Jones, S.; Kalas, P.; Lloyd, J.P.; Makidon, R.; et al. Extreme Adaptive Optics Planet Imager: XAOPI. In Proceedings of the Techniques and Instrumentation for Detection of Exoplanets, San Jose, CA, USA, 4–6 August 2003; Coulter, D.R., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 5164, pp. 272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Delorme, J.-R.; Jovanovic, N.; Echeverri, D.; Mawet, D.; Kent Wallace, J.; Bartos, R.D.; Cetre, S.; Wizinowich, P.; Ragland, S.; Lilley, S.; et al. Keck Planet Imager and Characterizer: A Dedicated Single-Mode Fiber Injection Unit for High-Resolution Exoplanet Spectroscopy. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2021, 7, 035006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, T.; Sauvage, J.-F.; Petit, C.; Costille, A.; Dohlen, K.; Mouillet, D.; Beuzit, J.-L.; Kasper, M.; Suarez, M.; Soenke, C.; et al. Final Performance and Lesson-Learned of SAXO, the VLT-SPHERE Extreme AO: From Early Design to on-Sky Results. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems IV, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 June 2014; Marchetti, E., Close, L.M., Véran, J.-P., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9148, p. 91481U. [Google Scholar]

- Vassallo, D.; Greggio, D.; Arcidiacono, C.; Ragazzoni, R. Spatial Filtering Applied to the Pyramid WFS: Simulations and Preliminary Results. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems VI, Austin, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Close, L.M., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- Martinache, F.; Guyon, O.; Jovanovic, N.; Clergeon, C.; Singh, G.; Kudo, T. On-Sky Speckle Nulling with the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme AO (SCExAO) Instrument. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems IV, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 June 2014; Marchetti, E., Close, L.M., Véran, J.-P., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9148, p. 914821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozi, J.; Guyon, O.; Jovanovic, N.; Goebel, S.; Pathak, P.; Skaf, N.; Sahoo, A.; Norris, B.; Martinache, F.; M’Diaye, M.; et al. SCExAO, an Instrument with a Dual Purpose: Perform Cutting-Edge Science and Develop New Technologies. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems VI, Austin, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Close, L.M., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, N.; Guyon, O.; Martinache, F.; Matsuo, T.; Yokochi, K.; Nishikawa, J.; Tamura, M.; Kurokawa, T.; Baba, N.; Vogt, F.; et al. An Eight-Octant Phase-Mask Coronagraph for the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme AO (SCExAO) System: System Design and Expected Performance. In Proceedings of the Ground-Based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy III, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 June–2 July 2010; McLean, I.S., Ramsay, S.K., Takami, H., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; Volume 7735, p. 773533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinache, F.; Jovanovic, N.; Guyon, O. Subaru Coronagraphic eXtreme Adaptive Optics: On-Sky Performance of the Asymmetric Pupil Fourier Wavefront Sensor. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems V, Edinburgh, UK, 26 June–1 July 2016; Marchetti, E., Close, L.M., Véran, J.-P., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; Volume 9909, p. 990954. [Google Scholar]

- Magniez, A.; Bardou, L.; Morris, T.J.; O’Brien, K. MKID: An Energy Sensitive Superconducting Detector for the next Generation of XAO Systems. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems VIII, Montréal, QC, Canada, 17–22 July 2022; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Vernet, E., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer, V.; Shatokhina, I. Advanced Wavefront Reconstruction Methods for Segmented Extremely Large Telescope Pupils Using Pyramid Sensors. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2018, 4, 049005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozi, J.; Guyon, O.; Jovanovic, N.; Takato, N.; Singh, G.; Norris, B.; Okita, H.; Bando, T. Characterizing Vibrations at the Subaru Telescope for the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics Instrument. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2018, 4, 049001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magniez, A.; Bardou, L.; Bond, C.Z.; Barr, D.; Escriche, M.; Geng, D.; Morris, T.J.; O’Brien, K.; Schwartz, N.; De Visser, P. A Polychromatic Pyramid Wavefront Sensor with MKID Technology for Extreme Adaptive Optics. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems IX, Yokohama, Japan, 16–22 June 2024; Schmidt, D., Vernet, E., Jackson, K.J., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Close, L.M.; Males, J.R.; Follette, K.B.; Hinz, P.; Morzinski, K.; Wu, Y.-L.; Kopon, D.; Riccardi, A.; Esposito, S.; Puglisi, A.; et al. Into the Blue: AO Science with MagAO in the Visible. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems IV, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 June 2014; Marchetti, E., Close, L.M., Véran, J.-P., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9148, p. 91481M. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, K.; Douglas, E.; Haffert, S.; Van Gorkom, K. Simulating the Efficacy of the Implicit-Electric-Field-Conjugation Algorithm for the Roman Coronagraph with Noise. In Proceedings of the Techniques and Instrumentation for Detection of Exoplanets XI, San Diego, CA, USA, 1–5 August 2023; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12680, p. 126800Z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffert, S.Y.; Males, J.R.; Close, L.; Guyon, O.; Hedglen, A.; Kautz, M.Y. Visible Extreme Adaptive Optics for GMagAO-X with the Triple-Stage AO Architecture (TSAO). In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems VIII, Montréal, QC, Canada, 17–22 July 2022; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Vernet, E., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Close, L.M.; Durney, O.; Males, J.R.; Kautz, M.Y.; Haffert, S.Y.; Fletcher, A.; Hedglen, A.; Gasho, V.; McLeod, A.L.; Sullivan, M.; et al. High-Contrast Imaging at First-Light of the GMT: The PDR Optical and Mechanical Design for the GMagAO-X ExAO System and Results from the HCAT Testbed with an HDFS Phased Parallel DM Prototype. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems IX, Yokohama, Japan, 16–22 June 2024; Schmidt, D., Vernet, E., Jackson, K.J., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Martinache, F.; Guyon, O. The Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme-AO Project. In Proceedings of the Techniques and Instrumentation for Detection of Exoplanets VI, San Diego, CA, USA, 2–5 August 2009; Shaklan, S.B., Ed.; Proceedings of SPIE. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2009; Volume 7440, p. 74400O. [Google Scholar]

- Vievard, S.; Ahn, K.; Arriola, A.; Barjot, K.; Cvetojevic, N.; Deo, V.; Gretzinger, T.; Gross, S.; Guyon, O.; Huby, E.; et al. Very High Resolution Spectro-Interferometry with Wavefront Sensing Capabilities on Subaru/SCExAO Using Photonics. In Proceedings of the Techniques and Instrumentation for Detection of Exoplanets X, San Diego, CA, USA, 1–5 August 2021; Shaklan, S.B., Ruane, G.J., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, N.; Echeverri, D.; Delorme, J.-R.; Finnerty, L.; Schofield, T.; Wang, J.J.; Xin, Y.; Xuan, J.W.; Wallace, J.K.; Mawet, D.; et al. Technical Description and Performance of the Phase II Version of the Keck Planet Imager and Characterizer. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2025, 11, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffert, S.Y.; Males, J.R.; Close, L.M.; Van Gorkom, K.; Long, J.D.; Hedglen, A.D.; Guyon, O.; Schatz, L.; Kautz, M.; Lumbres, J.; et al. Data-Driven Subspace Predictive Control of Adaptive Optics for High-Contrast Imaging. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2021, 7, 029001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyke, J.; Campbell, R.; Ghez, A.; Turri, P.; Ciurlo, A.; Do, T.; Witzel, G.; Lu, J.R.; Fitzgerald, M.P. Off-Axis PSF Reconstruction for Integral Field Spectrograph: Instrumental Aberrations and Application to Keck/OSIRIS Data. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems VI, Austin, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Close, L.M., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, B.R.M.; Martinod, M.-A.; Tuthill, P.G.; Gross, S.; Cvetojevic, N.; Jovanovic, N.; Lagadec, T.; Deyi Maria Klinner-teo, T.; Guyon, O.; Lozi, J.; et al. Optimal Self-Calibration and Fringe Tracking in Photonic Nulling Interferometers Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Optical and Infrared Interferometry and Imaging VIII, Montréal, QC, Canada, 17–22 July 2022; Mérand, A., Sallum, S., Sanchez-Bermudez, J., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Vazimali, M.G.; Fathpour, S. Applications of Thin-Film Lithium Niobate in Nonlinear Integrated Photonics. Adv. Photon. 2022, 4, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badloe, T.; Lee, S.; Rho, J. Computation at the Speed of Light: Metamaterials for All-Optical Calculations and Neural Networks. Adv. Photonics 2022, 4, 064002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predecessor Technology | Innovations Absorbed by LIFE | Upgrade Point |

|---|---|---|

| Dragonfly | Photonic chip thermo-optic phase shift | Space radiation-resistant version (single-event rollover rate < 10−7) |

| GLINT | Single-mode waveguide turbulence filtering | No filtering required (no turbulence in space) |

| LBTI | Mid-infrared band advantage | Extends to 18 μm (covers more molecules) |

| Technical Name | Nulling Interferometry | Spectral Band | Resolution (of a Photo) | Special Advantages (Other Data) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHANA Phase II | ~10−4 | Near-infrared bands (J, H, K) vary at different | Varies at different | Low-loss transmission using fiber-optic connection technology, up to 500 m fiber length, maximum propagation loss of 1 dB, transmission efficiency conservatively estimated at 50%. |

| MIRC-X | Better than 1 degree (closed phase accuracy) | Near-infrared (J and H bands, future plans include K band) | Equivalent to the angular resolution of up to 330 m diameter baseline telescopes (~0.6 mas) | Sensitivity improved by about two magnitudes compared to its predecessor MIRC, C-RED ONE camera adopted, readout noise below 1 electron/pixel |

| LBTI, NIC (NOMIC/LMIRcam) | NOMIC: Relative tilt of less than approx. 3 mas is required for a zero suppression of 10−4 (depth of zero suppression not directly given) | NOMIC: 7–25 microns; LMIRcam: 3–5 microns | NOMIC: 0.1–0.35 arcsec (7–25 microns); LMIRcam: 0.04–0.07 arcsec (3–5 microns) | NOMIC: N = 0.1 mJy in 1 h, spectral resolution 100; LMIRcam: L’ = 20, M = 17 in one hour, spectral resolution 350 |

| GLINT | ~10−4 (reached during testing in the sky) | 1.6 micron (1600 nm) with 50 nm bandwidth | ~25–60 mas | Single photonic chip design for high stability and compactness, with future plans to increase the number of baselines to improve sensitivity |

| LIFE Cluster | Contrast ratio will achieve 10−7 (10 μm, sun-to-Earth analogy) | 4 to 19 microns (mid-infrared) | Improved detection sensitivity and contrast through five-telescope kernel nulling beam synthesizer design | The five-telescope kernel nulling beam synthesizer is designed with redundancy so that even if one or both telescopes fail, the system will continue to produce robust observable data |

| Typology | Working Position | Core Objective | Typical Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| External-occultation Coronagraph | Positioned thousands to tens of thousands of kilometers in front of the space telescope. | Suppression of direct sunlight and observation of the low-altitude corona | Space solar observation |

| Lyot Coronagraph | Fully integrated within the telescope’s internal optical system. | Blocking stellar light and suppressing diffracted stray light | Ground-based planetary observations (e.g., Io plasma rings) |

| CPA Coronagraph | Primary modulation is applied at the telescope’s pupil plane (typically the exit pupil). | Modulation of optical pupil amplitude distribution for broadband imaging | Space broadband astronomical observations |

| Timing | Milestone | Teams | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Development of the PIAA concept | Subaru Telescope, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan | Theoretical throughput > 95% (A conceptual breakthrough) |

| 2005 | First experimental system validation | Subaru Observatory | Contrast ratio 10−6 (Visible light; initial on-sky validation) |

| 2009 | Reflective PIAA + Anamorphic Mirror Correction | NASA Ames | Contrast ratio 5 × 10−9 (650 nm monochromatic light; approaching fundamental limits in the lab) |

| 2013 | Vacuum environment polarization optimization | JPL | Contrast ratio 5 × 10−10 (Monochromatic light; represents the ultimate performance under ideal, narrowband conditions) |

| 2018 | PIAACMC adapted to WFIRST blocking pupil | NASA Goddard | Contrast ratio 1.8 × 10−7 (Achieved under 10% broadband light and a complex, obstructed pupil, demonstrating robustness for a real space mission) |

| 2024 | Liquid Crystal SLM Dynamic PIAA (lab phase) | Nanjing Institute of Astronomical Optics & Technology, National Astronomical Observatories, CAS | Contrast ratio 10−6 (4-12 λ/D under stitched mirrors; a new, active approach in development) |

| Norm | CPA | PIAA | PIAACMC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 15–30% | >90% | 70–85% |

| Inner working angle (λ/D) | 4–6 | 2–3 | 1.5–2.5 |

| Operating bandwidth | Wide (>20%) | Medium (10–15%) | Wide (>20%) |

| processing difficulty | Low (coated mask) | Media (aspheric) | High (hybrid devices) |

| Typical tasks | SPICA | Subaru SCExAO | WFIRST/CGI |

| Comparison Term | AO Technology | ExAO Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Wavefront Correction Accuracy | Achievement of a certain Strehl ratio (usually higher than 0.3–0.5) | Higher wavefront correction accuracy is required, typically to achieve Strehl ratios close to 1 (>0.9) |

| Calibration Speed | Usually between a few hundred Hz and a thousand Hz. | Higher calibration speeds are required (typically over a thousand Hz) |

| Correction Order | Typically lower order DMs are used, such as tens to hundreds of actuators | Requires higher-order morphing mirrors, often containing thousands of actuators |

| Contrast Performance | Limited contrast performance, often difficult to achieve contrast ratios of 10−6 or higher | Requires higher contrast performance, typically 10−7 to 10−10 contrast ratio is required |

| Wavefront Sensor | Possible use of Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensors, etc., but limited order and accuracy | Need for higher order wavefront sensors such as pyramidal wavefront sensors |

| Wavefront Control Algorithm | Using basic wavefront correction algorithms such as integral controllers | Need for more advanced wavefront control algorithms such as model predictive control or optimal control algorithms |

| Environmental Stability | Typically operated on ground-based telescopes, which need to cope with atmospheric turbulence, but the requirements for environmental stability are less stringent than for the ExAO system | Requires extreme thermal and mechanical stability control of the optical system |

| Photonic Noise Suppression | Although photon noise is also considered, it is not a major limiting factor in high contrast imaging | Special attention needs to be paid to the suppression of photonic noise |

| Coronagraphs and Post-Processing Techniques | Possible use of basic coronagraphs to suppress stellar light, but limited post-processing techniques | The need for more advanced coronagraph designs, such as vector vortex coronagraphs, as well as sophisticated post-processing techniques, such as differential imaging and angular differential imaging |

| Parameters | Conventional CCD | MKID |

|---|---|---|

| time resolution | typically ≤500 Hz | 1–10 kHz (10–100 times better turbulence-tracking capability) |

| wavelength resolution | Δλ/λ ≈ 0.05–0.1 (filter dependent) | Δλ/λ ≤ 0.005 (10–20 times higher dispersion-correction accuracy) |

| Sensitivity (noise) | Readout noise 3–5 e−/pix | Theory is zero readout noise (20–40 dB improvement in low-light signal-to-noise ratio) |

| Case (Law) | ExAO Role | Coronagraph | Nonzero Interference Effect | Coupling Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VLT-SPHERE | Suppression of static aberration (λ/100 RMS) | Creating polarized dark zones | Central stellar residual-light offset | Contrast improved 100-fold |

| Keck interferometer | Phase lock (Δφ < λ/200) | Front-diffraction light filtering | Mid-infrared stellar optical-coherence cancelation | Depth of Nulling deepened 100-fold |

| CSST | On operate jitter suppression | Compression of internal working angle to 1.5 λ/D | Extension of valid points | Signal-to-noise ratio improved times |

| Technical Name | Parameters | Technical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| OHANA Phase II | Spectral band: near-infrared (NIR) band (J, H, K) Maximum length of optical fiber: approximately 500 m Propagation loss: 1 dB maximum Transmission efficiency: conservative estimate of 50% Sensitivity: K = 13 ± 1 (when using an 8 m telescope) | Low-loss transmission using fiber-optic connection technology to verify the feasibility and performance of fiber-optic connection interferometers |

| MIRC-X | Closure Phase Accuracy: better than 1° Spectral Band: near-infrared (J and H bands) Angular Resolution: equivalent to that of a baseline telescope up to 330 m in diameter (0.6 mas) Sensitivity Improvement: approximately two magnitudes | Sensitivity improved by approximately two orders of magnitude compared to its predecessor MIRC, enabling high-resolution interferometric imaging and precise model-independent detection of asymmetries (e.g., from exoplanets or stellar spots). The high closure phase precision (<1°) is crucial for this. |

| LBTI, NIC | Operating Band: Thermal infrared (>2.5 µm), utilizing NOMIC (7–25 µm) and LMIRCam (3–5 µm) cameras. Key Achievement: Demonstrated nulling interferometry from the ground, studying exozodiacal dust and giant planets. | A premier ground-based interferometer showcasing the power of traditional bulk optics for high-contrast mid-infrared astronomy. It operates as a nulling interferometer and imager. |

| Integrated photonic technology | Representative Instruments: GLINT: Operates at 1.6 µm, achieving null depths ~10−4 on the Subaru telescope. GRAVITY/PIONIER (VLTI): Use photonic beam combiners for astrometry and imaging. Dragonfly/Hi-5: Pathfinder instruments demonstrating on-chip beam combination. LIFE Mission Concept: Plans to use advanced photonic kernel-nulling in the mid-infrared (4–18 µm). | Enhanced optical-system performance, cost-effectiveness, and scalability. Achieved high sensitivity nulling interferometry and advanced the development of exoplanet-detection technology in the mid-infrared band. |

| Improved Lyot Coronagraph | Contrast ratio: up to 3 × 10−10 (within two circular fields of view ranging from 3 λ/D to 15 λ/D) Operating spectrum: broadband | Improved luminous efficacy and internal working angle for broadband operation |

| Flat Top Sinusoidal Phase-plate Coronagraph | Contrast ratio: 10−3 in the wavelength range of 490–620 nm for stellar-light extinction. Operating spectrum: 490–620 nm | Combined the advantages of the sinusoidal phase plate coronagraph and six-platform phase-plate coronagraph to achieve a balance of broadband operation and high-contrast imaging |

| Phase-induced Amplitude Toe-cut Coronagraph (PIAA) | Contrast: Theoretically capable of achieving near 100% luminous efficacy and 10−10 contrast imaging at an angle of 2 λ/D. Inner working angle: small | Overcame the traditional optical pupil cut-toe-type coronagraph low-throughput, large internal working angle, and other shortcomings |

| PIAA combined with Lyot Coronagraph | Contrast ratio: 2.6 × 10−8 for 650 nm monochromatic incident light, 1.8 × 10−7 for 10% bandwidth complex color light | Enabled the application of PIAA to complex optical-pupil shapes and further improved performance |

| SCExAO system | Contrast: 5σ contrast curves were achieved for fifth-magnitude stars at 5 h of integration time, with 10−5, 2 × 10−6, and 10−6 contrast at 0.25″, 0.4″, and 0.8″, respectively Spectral band: Visible to near-infrared band (approx. 500–900 nm) | High-contrast imaging was achieved and several exoplanets were successfully detected |

| Pyramid Wavefront Sensor | Accuracy: Improved accuracy of wavefront detection Spectral band: Multi-band | Utilized pyramid-shaped optics to divide the spot into four quadrants for improved wavefront-detection accuracy |

| Microwave Kinetic-inductance Detector (MKID) applied to PWFS | Provides higher performance than conventional CCD/CMOS detectors, especially in terms of high pixel count, high frame rate, and low readout noise | Enhanced performance of pyramidal wavefront sensors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, Z.; An, Q.; Yang, C.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Roadmap for Exoplanet High-Contrast Imaging: Nulling Interferometry, Coronagraph, and Extreme Adaptive Optics. Photonics 2025, 12, 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12101030

Guo Z, An Q, Yang C, Hu J, Li X, Wang L. Roadmap for Exoplanet High-Contrast Imaging: Nulling Interferometry, Coronagraph, and Extreme Adaptive Optics. Photonics. 2025; 12(10):1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12101030

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Ziming, Qichang An, Canyu Yang, Jincai Hu, Xin Li, and Liang Wang. 2025. "Roadmap for Exoplanet High-Contrast Imaging: Nulling Interferometry, Coronagraph, and Extreme Adaptive Optics" Photonics 12, no. 10: 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12101030

APA StyleGuo, Z., An, Q., Yang, C., Hu, J., Li, X., & Wang, L. (2025). Roadmap for Exoplanet High-Contrast Imaging: Nulling Interferometry, Coronagraph, and Extreme Adaptive Optics. Photonics, 12(10), 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12101030