Abstract

Fresnel wave surfaces, or isofrequency light shells, provide a powerful framework for describing electromagnetic wave propagation in anisotropic media, yet their applicability is restricted to reciprocal, lossless materials and far-field radiation. This paper extends the concept by incorporating near-field effects and non-Hermitian responses arising in media with loss, gain, or non-reciprocity. Using the Om-potential approach to macroscopic electromagnetism, we reinterpret near fields as off-shell electromagnetic modes, in analogy with off-shell states in quantum field theory. Formally, both QFT off-shell states and electromagnetic near-field modes lie away from the dispersion shell; physically, however, wavefunctions of fundamental particles admit no external sources (virtual contributions live only inside propagators), whereas macroscopic electromagnetic near-fields are intrinsically source-generated by charges, currents, and boundaries and are therefore directly measurable—for example via near-field probes and momentum-resolved imaging—making “off-shell” language more natural and operational in our setting. We show that photonic density of states (PDOS) distributions near Fresnel surfaces acquire Lorentzian broadening in non-reciprocal media, directly linking this effect to the Beer–Bouguer–Lambert law of exponential attenuation or amplification. Furthermore, we demonstrate how Abraham and Minkowski momenta, locked to light shells in the far field, naturally shift to characterize source structures in the near-field regime. This unified treatment bridges the gap between sources and radiation, on-shell and off-shell modes, and reciprocal and non-reciprocal responses. The framework provides both fundamental insight into structured light and practical tools for the design of emitters and metamaterial platforms relevant to emerging technologies such as 6G communications, photonic density-of-states engineering, and non-Hermitian photonics.

1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) seeks to integrate the physical, chemical, biological, and digital domains through their common electromagnetic foundation [1]. At the most fundamental level, systems ranging from atoms and living cells to magnetoplasmas can be understood as electromagnetic charge–field systems. Recent work introducing the “Om” -theory of macroscopic electromagnetism has proposed the Om-potential as a framework that unifies sources and fields, providing a universal language that can connect natural processes, technological systems, and even philosophical models [2].

In practice, 4IR is currently driven by the demand for advanced communications technologies enabling artificial intelligence (AI), machine-to-machine interaction, the Internet of Things (IoT), swarm robotics, and related capabilities [3]. Overcoming existing limitations will require conceptual advances comparable in impact to the steam engine, alternating-current power distribution, or semiconductors. The Om-potential approach suggests one such advance: rethinking the holistic design of emitters and structured electromagnetic fields embedded in anisotropic or non-Hermitian materials. This perspective aligns with strategies proposed for next-generation (e.g., 6G) telecommunications, which emphasize phased arrays, mode multiplexing, structured light for attenuation compensation, and the use of metamaterials along with non-reciprocal or non-Hermitian media [4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Classical electromagnetic theory distinguishes near fields and far fields via their reactive and radiative components. In lossless isotropic media, far fields decay as , reflecting intensity divergence over solid angle [11,12]. These far fields are solutions of the homogeneous Maxwell equations, representing radiation in the absence of sources. Conceptually, they correspond to placing sources at infinity and assuming propagation without scattering or absorption. By contrast, in media with loss or gain, far fields are modulated by exponential attenuation or amplification described by the Beer–Bouguer–Lambert (BBL) law [13,14,15].

Isofrequency surfaces—also known as Fresnel wave surfaces or light shells—encode the topological features of dispersion in momentum () space, playing a central role in anisotropic and hyperbolic media [16,17]. They are closely connected to phenomena such as modified photonic density of states (PDOS), Purcell-type emission enhancements [18,19], and the distinction between Abraham and Minkowski momenta, which arise from refraction and ray-wave tilt [20,21,22]. However, Fresnel wave surfaces have been fully developed only for reciprocal, lossless materials and strictly capture far-field behavior. Near fields, in contrast, correspond to solutions of inhomogeneous Maxwell equations, and thus lie outside this framework—leaving a key theoretical gap directly addressed by -theory (see Figure 1 for metaphorical illustration) [2].

Figure 1.

Metaphorical illustration. The conch’s surface represents the isofrequency light shell, while its finite wall thickness symbolizes the Lorentzian broadening from loss. The mark denotes the Om-potential, linking the off-shell near fields to the radiating on-shell surface.

In non-Hermitian media, fields undergo exponential attenuation or amplification in accordance with the BBL law, a phenomenon of particular current interest for structured light carrying orbital angular momentum (OAM) [23,24]. However, this behavior cannot be represented within the conventional Fresnel-wave-surface formalism. A new framework is therefore required—one that retains the descriptive power of light shells while extending naturally to near-field regimes and non-Hermitian responses.

In this paper, we bridge that gap by directly linking Fresnel wave surfaces with PDOS in momentum space, showing that direction-dependent BBL extinction or amplification can be modeled as Lorentzian broadening of the surfaces. Within the Om-potential framework, we interpret off-shell electromagnetic modes as near fields, and we demonstrate that quantities traditionally associated with light shells in the far field—such as Abraham and Minkowski momenta and wavefront curvature—shift naturally toward characterizing source structure in the near-field regime.

2. ॐ-Theory

In the presence of electric and magnetic sources and , macroscopic electromagnetic fields satisfy Maxwell’s equations

The constitutive relations are written in block form [25],

where and are, in general, anisotropic and may include gyrotropy (Faraday rotation) and hyperbolicity, while the magnetoelectric blocks and encode bianisotropy (e.g., optical activity/chirality and related linear/circular dichroism). Non-Hermitian parts encode loss/gain, and anti-Hermitian components capture non-reciprocal response [26]. Standard reciprocal subclasses (e.g., uniaxial/biaxial dielectrics, reciprocal pseudo-chiral media) follow as constrained instances of . In the calculations below we adopt a generic, fully populated bianisotropic effective matrix—with randomized entries and controlled non-Hermitian components to include all these effects and evaluate the derived expressions numerically to obtain the light shells and associated PDOS.

Equations (1) and (2) can be combined into the matrix form

with the operator .

One common way to express the fields generated by sources is to use the Green’s function

Alternatively, the solutions to Equation (3) can be obtained using the -potential approach [2]

where the -potential is represented by .

The operators are defined via their Fourier representation:

Finally, in the momentum space, the Green’s function is related to the -potential approach as

3. Beyond Light Shells

Fresnel wave surfaces represent the set of points in momentum space corresponding to plane waves that can propagate in a material at a given frequency. These surfaces are also known as isofrequency surfaces. In this work, we adopt the term light shells to emphasize the analogy with mass shells for massive particles in quantum field theory. This terminology allows us to classify far-field states located on the Fresnel wave surfaces as on-shell waves, while states with real k-vectors not belonging to the Fresnel surface are regarded as off-shell waves. Our use of “on/off-shell” language follows standard spectral/Green-function terminology, where poles of the propagator correspond to on-shell states and detuned contributions are off-shell (see Refs. [27,28] and Equation (8) for the link to the Green-function representation). We also employ the Om-potential terminology introduced in our peer-reviewed work [2]; to the best of our knowledge there is no alternative terminology, and we therefore use it consistently as the presently sole existing standard source–field framework in this manuscript.

Mathematically, Fresnel wave surfaces are defined by the dispersion condition

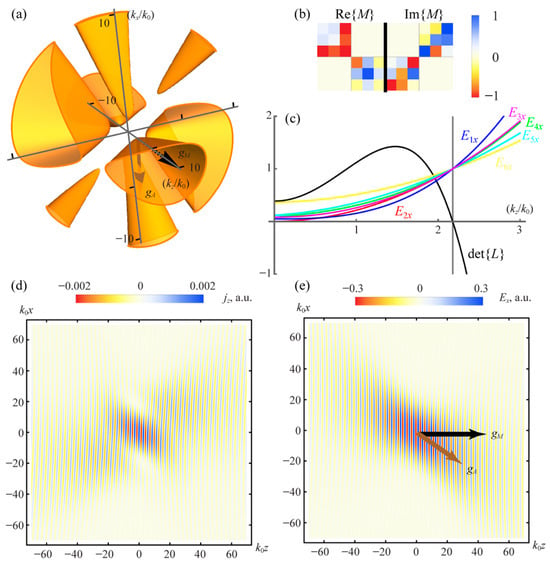

As an example, Figure 2a shows a light shell corresponding to the material parameters matrix depicted in Figure 2b. The hyperbolic response of this randomized example is visible directly in Figure 2a through the open (non-closed) regions of the light shell, while the underlying constitutive matrix used to generate it is shown in Figure 2b. These plots are produced by numerically evaluating our analytical expressions for the chosen 6 × 6 effective material, confirming that the results presented here are fully quantitative.

Figure 2.

(a) Fresnel wave surface (light shell) corresponding to the material parameters matrix shown in panel (b). The directions of the Minkowski momentum and Abraham momentum are indicated for a representative on-shell plane wave. (b) Real and imaginary parts of the material parameters matrix used to generate the surface in panel (a). (c) Dependence of the dispersion determinant on for the same material. Also shown are the components of all six columns of the operator ; these components become identical at the on-shell condition . (d) External source distribution exciting the medium in paraxial approximation. (e) Resulting field of a Gaussian beam composed of on-shell states in the same approximation. The beam propagates along the Abraham momentum axis , illustrating Minkowski–Abraham momentum locking.

Since for on-shell far-fields, the operator becomes singular, and all of its columns are proportional to the field amplitude eigenvector of the corresponding plane wave. This behavior is illustrated in Figure 2c, where the dependence of on is plotted for the same material as in Figure 2a,b. In Figure 2c, we plot the component of all six columns of the matrix, which coincide when corresponds to the on-shell condition .

Light shells determine not only the phase of far-field waves but also their polarization. The wave vectors k lying on the light shells are aligned with the Minkowski momentum, whose density is

This alignment arises because far-field solutions exclude external charges, enforcing the transversality conditions and . Normals to the light shells, on the other hand, are directed along the Abraham momentum

whose misalignment with respect to the k-vectors reflects the generation of bound charges in isotropy-broken media [21,22]. An example of this Minkowski–Abraham momentum locking is shown in Figure 2a for a plane wave with k parallel to the z-axis.

The Minkowski–Abraham momentum locking influences both fundamental and structured beams in isotropy-broken media, giving them a characteristic biaxial nature. This effect is illustrated in Figure 2d,e. As a first example, we consider a Gaussian beam represented in terms of the Om-potential:

where and denote the beam envelopes. The spatial harmonics of such a beam lie on the light shell in the paraxial approximation. Due to Minkowski–Abraham momentum locking, the phase of the beam propagates along the Minkowski axis, whereas the beam ray itself is directed along the Abraham axis, consistent with Ref. [21].

In the paraxial approximation, the spatial harmonics of the beam correspond to the parabola tangent to the Fresnel wave surface, obtained from the Taylor expansion of the dispersion relation

where constant , is the Abraham momentum density, and is the Hessian matrix of the Fresnel wave surface at the central -vector.

In Figure 2d we show the distribution of external sources corresponding to the -potential with the same central wave vector as discussed in Figure 2a. These sources are small in magnitude and arise from the deviation of the paraxial approximation from the exact solution of Maxwell’s equation given by Equation (5). The associated field distribution of this biaxial Gaussian beam is presented in Figure 2e. The field differs from the exact homogeneous Maxwell solution only because of the paraxial approximation and is therefore representative of the far-field regime.

To investigate near-fields, we turn to the off-shell spatial harmonics. Departing from the paraxial approximation, we construct the beam from spatial harmonics lying in the plane perpendicular to the Abraham momentum at wave vector , i.e., satisfying

In this regime the external sources can no longer be neglected, and Equation (9) applies:

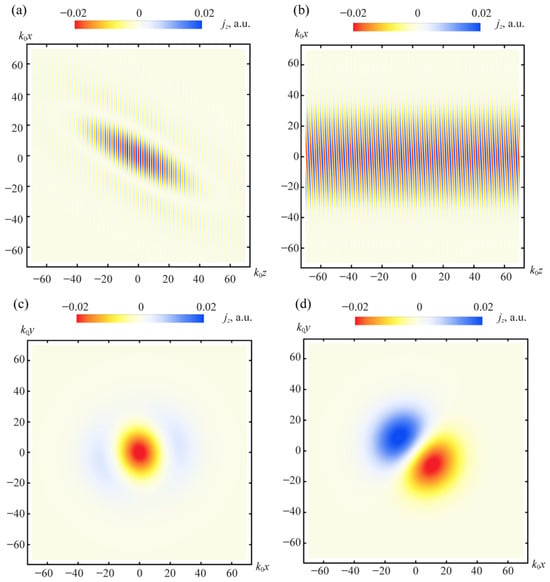

The external sources defined by Equation (9) are illustrated in Figure 3a (in the x–z plane) and Figure 3c (cross-section in the x–y plane at ). One can see that the wavefronts in this case are flat.

Figure 3.

External sources defined by Equation (9) (a) in x-z plane and (c) in x-y plane at ; External sources given by Equation (10) (b) in x-z plane and in x-y plane (c) at ; (d) at .

In the more general case of a Gaussian beam centered at a wave vector on the light shell, the sources are

This expression clarifies the role of the Abraham momentum. In the far-field regime, it determines the direction of beam propagation. By contrast, for off-shell spatial components whose k-vectors deviate from the Fresnel wave surface, the Abraham momentum is no longer a property of the field itself but instead characterizes the external sources. In this picture, sources are expressed as directional derivatives of the -potential envelope along the Abraham momentum direction.

For a Gaussian beam composed of spatial harmonics lying in the plane tangent to the Minkowski momentum condition , the external sources defined by Equation (10) are shown in Figure 3b in the x–z plane and Figure 3c in the x–y plane at , and in Figure 3d at . Note that the cross-section at is the same for the sources described by Equations (9) and (10). The additional first term in Equation (10) modifies the cross-section at , producing the distribution shown in Figure 3d. It should be emphasized that the first and second terms in Equation (10) are out of phase.

The resulting field distributions produced by these sources are presented in Figure 4. Since all spatial harmonics in these pulses remain close to the Fresnel wave surface, the matrices are still ill-conditioned, and the polarization is only weakly perturbed from its far-field direction at the Fresnel surface. The perturbation depends only slightly on the orientation of the -potential.

The Gaussian beam serves as the simplest example to illustrate the connection between the Om-potential, source distributions, and Fresnel wave surfaces. As discussed in Ref. [21], biaxial and other structured beams in anisotropy-broken media can be viewed as superpositions of on-shell states confined to specific regions of the Fresnel surface. The present formalism is fully general and naturally extends to higher-order structured beams such as Laguerre–Gaussian and Hermite–Gaussian modes to off-shell states, which correspond to higher-order solutions of the same Om-potential equations. A detailed analysis of these effects will be presented in future work.

If the spatial harmonics of a beam with central wave vector lie far from the Fresnel wave surface in momentum space, then is nonzero and acts as a scalar proportionality factor between the external sources and the -potential:

This relation shows that the orientation and type of external sources are dictated by the polarization of the -potential. In this case, both the and operators are well-conditioned, and the electromagnetic fields depend explicitly on the external sources:

4. Beyond Reciprocal Media: Lorentz Broadening of Light Shells and BBL

In reciprocal materials, Fresnel wave surfaces are well defined by the dispersion condition . By contrast, the Fresnel wave surfaces of non-reciprocal media are the subject of active research in modern optics [29]. The difficulty lies in the fact that, for non-reciprocal materials, is a complex quantity [30]. As a result, the conditions and define curves rather than a single closed surface in the space of real wave vectors [31].

In many treatments, one therefore considers complex wave vectors that satisfy . In this case, the Fresnel wave surface is represented in the momentum space of the real parts , while the imaginary parts are not investigated [29].

The imaginary components of play a crucial role in energy balance during plane-wave propagation in non-reciprocal media with loss or gain. This results in exponential attenuation or amplification of electromagnetic fields—a process captured by the Beer–Bouguer–Lambert (BBL) law. While the BBL law has long been recognized in many branches of science, its implications for isotropy-broken media have not been systematically studied.

In what follows, we develop a unified framework for Fresnel wave surfaces in non-reciprocal media. The approach models Lorentzian broadening of light shells, explicitly incorporates BBL-type exponential modulation, and keeps the description in real k-space.

From Maxwell’s equations, we obtain the following relationship

Introducing the bound currents,

the material absorption (work performed on bound charges/currents) can be written as

The power exchanged with external sources is

Taking the imaginary part of Equation (11) yields

which shows that the energy delivered by sources during one optical period is partitioned into (i) local work of electromagnetic fields on bound currents in the material (true absorption/gain), and (ii) a term proportional to , which produces exponential attenuation or amplification of the fields—i.e., the Beer–Bouguer–Lambert effect.

In reciprocal, lossless media the field–material exchange is purely reactive, so . If, additionally, there is no decay or gain (), the exchange with external sources is also purely reactive, . This conclusion does not apply on the Fresnel wave surface where , and therefore diverges [see Equation (8)]; any nonzero external current then drives fields that diverge.

This gives a clue for generalizing the Fresnel wave surface concept to non-reciprocal media. Consider an external electric source polarized along : . The energy exchanged between the field and the source is

Here the photonic density of states (PDOS) for the x-polarization is

using .

From Equation (5) we have

The overall field phase can be chosen so that real.

Now consider the PDOS near the Fresnel wave surface, where . Linearizing,

With the renormalization , we get

where the surface density of states (SDOS) is

Intuitively, is the slope of along the surface normal, while sets the Green-function residue for the chosen polarization; their ratio thus defines the surface density of states on the Fresnel wave surface.

To include non-reciprocity, perturb the constitutive matrix

so that in Fourier space .

Using Jacobi’s formula,

Near the Fresnel surface we obtain

where is the complex index of refraction corresponding to a solution of . Therefore, in media with gain or loss the polarization-specific PDOS becomes

Here is the Lorentzian function. Note that in reciprocal materials and giving a delta-functional density of states peaking on the Fresnel wave surface. As seen from Equation (12), this relates Fresnel wave surfaces directly to the PDOS in momentum space and shows that non-reciprocity produces a Lorentzian broadening of the surface in PDOS. The width of this broadened PDOS is proportional to the imaginary part of the direction-dependent refractive index , which links the broadening to direction-dependent BBL extinction or amplification of electromagnetic waves in non-reciprocal media.

To clarify the meaning of our results, consider the case of amplification. The BBL modulation then has the form , which corresponds to a negative . By Equation (12) this produces a negative PDOS . Because the source–field power exchange is , a negative implies : the electromagnetic field returns active power to the source.

In real k-space we set , so we have . Thus identifies gain: the material does work on the field, and the field delivers power back to the source. By contrast, for loss () we have and , which is the usual situation where power flows from the source to the field and is then dissipated in the material.

In the reciprocal, lossless case , the BBL effect vanishes, and the exchange is purely reactive, so over one optical period. The PDOS collapses to a delta peak on the Fresnel surface, reflecting an undamped on-shell mode. Exactly on the shell the Green’s function is singular, so any finite source would diverge in the idealized model; in practice, small damping always regularizes this to a narrow, symmetric Lorentzian.

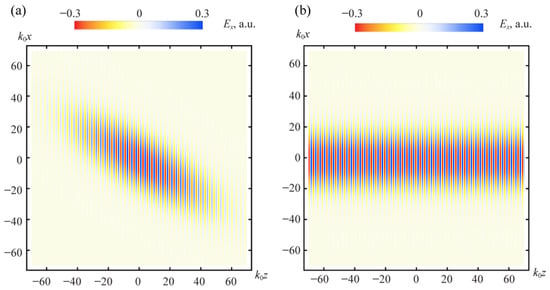

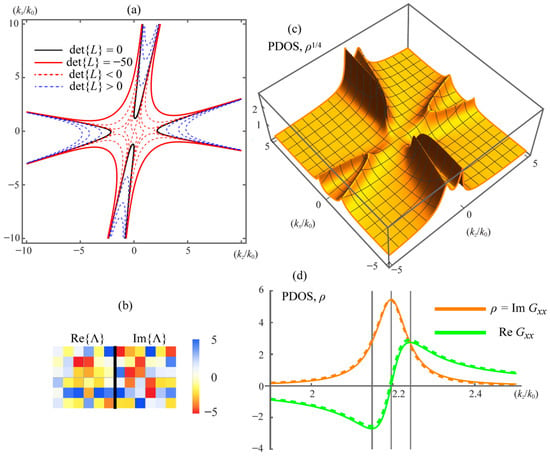

Figure 5 summarizes the non-reciprocal case and the emergence of Lorentzian PDOS broadening. Figure 5a shows a – cross-section of the light shell for the reciprocal reference medium, with the on-shell contour (black) and representative level sets of (line styles indicating sign). Figure 5b displays the real and imaginary parts of the perturbation matrix (color-coded), which we add to the reciprocal constitutive matrix of Figure 2b to introduce direction-dependent non-Hermitian response and non-reciprocity. In this example, contains (i) antisymmetric components in the and sub-blocks that generate gyrotropic (Faraday-like) rotation, (ii) nonzero magneto-electric cross-couplings that encode optical activity (chirality) and related bianisotropic effects, and (iii) imaginary parts across these blocks that implement non-Hermitian response. The perturbation amplitudes are chosen small enough to remain near the reciprocal shell yet large enough to resolve the broadening. Figure 5c plots the PDOS map in the – plane for the non-reciprocal medium defined by (Figure 2b) and (Figure 5b), computed via Equation (12). Figure 5d shows a lineout of the PDOS versus together with a Lorentzian fit near the Fresnel surface; the vertical markers denote the peak position and FWHM, explicitly evidencing the Lorentzian broadening predicted by Equation (12).

Figure 5.

(a) - cross-section of the light shell from Figure 2a. Shown are the on-shell contour (black) together with representative level sets for and (line styles indicate the sign). (b) Real and imaginary parts of the constitutive matrix used for panels (c,d) (color-coded). (c) PDOS map in - plane for the non-reciprocal medium defined by in Figure 2b and in (b) with computed from . (d) Lineout of the PDOS (orange) and (green) versus (solid) along the -axis in (c) and the corresponding Lorentzian fit near the Fresnel wave surface (dashed); the vertical bars mark the peak position (center) and the full width at half maximum (side bars), evidencing the Lorentzian broadening of the Fresnel wave surface predicted by Equation (12).

5. Discussion

We have extended the classical framework of Fresnel wave surfaces to encompass near-field regimes, non-reciprocal responses, and media with loss or gain. By employing the Om-potential approach, we established a unified description that treats far-field states as on-shell modes and near-field contributions as off-shell modes, directly paralleling concepts from quantum field theory. This interpretation clarifies the role of Abraham and Minkowski momenta, which in far-field propagation are locked to light shells but, in the near-field regime, emerge as descriptors of source structure.

A key result of this work is the demonstration that photonic density of states (PDOS) in non-reciprocal and non-Hermitian media exhibits Lorentzian broadening around Fresnel wave surfaces. This broadening provides a direct connection between the Beer–Bouguer–Lambert law of exponential attenuation or amplification and the momentum-space topology of electromagnetic fields. In this way, we bridge a theoretical gap by linking the physics of sources, near fields, and structured radiation to established tools of dispersion theory.

Beyond its conceptual significance, the proposed framework offers practical value for the design of emitters, metamaterials, and structured-light systems. It suggests new approaches for tailoring PDOS and source–field interactions in anisotropic, hyperbolic, and non-Hermitian photonic platforms. Such advances are directly relevant to emerging applications including 6G telecommunications, multiplexing via structured light, and topological photonics.

Angle-resolved reflectometry/ellipsometry can retrieve the direction-dependent imaginary part of the refractive index, , in anisotropic or gyrotropic media. Paired with momentum-resolved (k-space) imaging—e.g., back-focal-plane or leakage-radiation microscopy, or angle-resolved cathodoluminescence—to measure isofrequency contours (Fresnel wave surfaces) and their finite linewidths. Notably, finite linewidths of isofrequency contours have already been reported in k-space imaging of photonic structures [32], and photonic time-crystal experiments report negative photonic density-of-states features associated with gain-assisted, non-Hermitian dynamics—evidenced by spontaneous excitation and LDOS lineshapes in time-modulated platforms [33]. Together, these precedents support the feasibility of the ellipsometric–k-space comparison envisioned here and provide experimental context for our PDOS interpretation in active media. As a complementary probe of the near-field regime and Minkowski–Abraham momentum behavior, NSOM or EELS can map local amplitude and phase to identify off-shell components and elucidate the source–field relationships central to our framework.

Future work may expand these ideas toward explicit experimental verification, numerical modeling of PDOS broadening in specific material systems, and integration with non-Hermitian photonic devices. By reconciling on-shell and off-shell modes, near and far fields, and reciprocal and non-reciprocal responses, this work opens pathways to both deeper fundamental understanding and new technological frontiers in photonics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.; methodology, M.D.; software, M.D. and D.K.; validation, M.D. and D.K.; formal analysis, M.D.; investigation, M.D.; resources, M.D.; data curation, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.; writing—review and editing, M.D. and D.K.; visualization, M.D.; supervision, M.D.; project administration, M.D.; funding acquisition, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The authors appreciate the support of the Georgia Southern University in all other respects.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this text.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Center for Advanced Materials Science at Georgia Southern University. Figure 1 was drawn by Katie Durach. We thank Mario G. Silveirinha for referring us to Ref. [33].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; Currency: Redfern, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Durach, M. Beyond Green’s Functions: Inverse Helmholtz and “Om” ॐ-Potential Methods for Macroscopic Electromagnetism in Isotropy-Broken Media. Photonics 2025, 12, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejčí, J.; Babiuch, M.; Suder, J.; Krys, V.; Bobovský, Z. Internet of Robotic Things: Current Technologies, Challenges, Applications, and Future Research Topics. Sensors 2025, 25, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, Y.; Yun, J.; Moon, S.-W.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Park, J.; Badloe, T.; Kim, I.; Rho, J. Metasurface-driven full-space structured light for three-dimensional imaging. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrah, A.H.; Capasso, F. Tunable structured light with flat optics. Science 2022, 376, eabi6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasilainen, K.; Phan, T.D.; Berg, M.; Pärssinen, A.; Soh, P.J. Hardware Aspects of Sub-THz Antennas and Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces for 6G Communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2023, 41, 2530–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, F.; Kazmi, S.H.A.; Ariffin, K.A.Z.; Tayyab, M.; Nguyen, Q.N. Multi-Antenna Array-Based Massive MIMO for B5G/6G: State of the Art, Challenges, and Future Research Directions. Information 2024, 15, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Sen, P. Printed multiple-input multiple-output antennas powered by passive metamaterial and defected ground for diverse sixth-generation applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Qi, Z.J.; Wu, L.J.; Zhou, Q.Y.; Dai, J.Y.; Cao, W.W.; Ge, X.; Gao, C.L.; Gao, X.; Wang, S.R.; et al. A smart millimeter-wave base station for 6G application based on programmable metasurface. Nat. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, K.; Quan, Z. Integrated structured light manipulation. Photon. Insights 2024, 3, R05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.D. Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Born, M.; Wolf, E. Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference and Diffraction of Light; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mayerhöfer, T.G.; Pahlow, S.; Popp, J. The Bouguer–Beer–Lambert law: Shining light on the obscure. ChemPhysChem 2020, 21, 2029–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žitnik, M.; Krušič, Š.; Bučar, K.; Mihelič, A. Beer–Lambert law in the time domain. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 063424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshina, I.; Spigulis, J. Beer–Lambert law for optical tissue diagnostics: Current state of the art and the main limitations. J. Biomed. Opt. 2021, 26, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.; Wu, C.; Lepage, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Hyperbolic metamaterials and their applications. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2015, 40, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jiang, H.; Chen, H. Hyperbolic metamaterials: From dispersion manipulation to applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127, 071101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobozhanyuk, A.P.; Ginzburg, P.; Powell, D.A.; Iorsh, I.; Shalin, A.S.; Segovia, P.; Krasavin, A.V.; Wurtz, G.A.; Podolskiy, V.A.; Belov, P.A.; et al. Purcell effect in hyperbolic metamaterial resonators. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 195127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanth, K.V.; Krishna, K.H.; De Luca, A.; Strangi, G. Large spontaneous emission rate enhancement in grating-coupled hyperbolic metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S.M. Resolution of the Abraham–Minkowski dilemma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 070401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, M. Biaxial Gaussian Beams, Hermite–Gaussian Beams, and Laguerre–Gaussian Vortex Beams in Isotropy-Broken Materials. Photonics 2024, 11, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, M. Theory of Refraction, Ray–Wave Tilt, Hidden Momentum, and Apparent Topological Phases in Isotropy-Broken Materials Based on Electromagnetism of Moving Media. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, E.; Yu, B.; Huang, Z. Nonreciprocity with structured light using optical pumping in hot atoms. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2022, 18, 024027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Fu, Z.; Mao, W.; Qie, J.; Stone, A.D.; Yang, L. Non-Hermitian optics and photonics: From classical to quantum. Adv. Opt. Photon. 2023, 15, 442–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, T.G.; Lakhtakia, A. Electromagnetic Anisotropy and Bianisotropy: A Field Guide; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, M.V. The optical singularities of bianisotropic crystals. Proc. R. Soc. A 2005, 461, 2071–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M. Modern Particle Physics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 1: Foundations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fesenko, V.I.; Tuz, V.R. Lossless and loss-induced topological transitions of isofrequency surfaces in a biaxial gyroelectromagnetic medium. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 094404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, C.; Busch, K.; Mortensen, N.A. Modal expansions in periodic photonic systems with material loss and dispersion. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulkey, T.; Dillies, J.; Durach, M. Inverse problem of quartic photonics. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 1226–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, E.C.; Igarashi, Y.; Zhen, B.; Kaminer, I.; Hsu, C.W.; Shen, Y.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Soljačić, M. Direct imaging of isofrequency contours in photonic structures. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, K.; Zhang, R.-Y.; Park, H.-C.; Ryu, J.-W.; Cho, G.Y.; Lee, M.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Park, N.; Jeon, W.; et al. Spontaneous emission decay and excitation in photonic time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 135, 133801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).