Abstract

Conventionally used in astronomy, adaptive optics (AO) systems measure and correct for turbulence and, therefore, have the capability to mitigate the impact of the atmosphere on the ground-to-space communication links. Historically, there have been two main streams, respectively, advocating to use or not use adaptive optics on optical communications. This paper aims to present a comprehensive review of the field of AO-based uplink pre-compensation. It will cover the technical challenges associated with uplink correction, provide an overview of the state-of-the-art research and demonstrations from the early days to the present, and discuss the future prospects of AO-based uplink pre-compensation and potential trade-offs between performance, cost, and operational considerations.

1. Introduction

In the present and future era of space and ground assets, high data demands necessitate flexible network capabilities with large bandwidth. Optical communications offer a promising solution to this challenge, facilitating efficient, economically viable, global and integrated communications through optical inter-satellite links and optical space to/from ground transmissions. However, atmospheric turbulence poses a significant obstacle to the successful implementation of optical communications to and from the ground segment. The sensitivity of optical links to the atmosphere can lead to reductions of up to 10 times in the power reaching the satellite, significantly impairing the communications performance.

To overcome this limitation, adaptive optics (AO) offers a potential solution. AO systems are commonly employed in ground-based telescopes to compensate for light distortion caused by atmospheric turbulence. An AO system consists of a wavefront sensor (WFS) that measures real-time aberrations by imaging a reference light source in the sky and a deformable mirror (DM) that adjusts its shape to mitigate the undesirable effects on the light. A natural guide star (NGS) or a laser guide star (LGS) can serve as the reference light source. Advancements in AO technology are increasingly being applied to other domains, including optical communications through the atmosphere.

Space-to-ground optical links (downlinks) resemble the scenario encountered in astronomy where infrared laser light originating from the satellite travels downwards towards the Earth’s surface. This light is then received by an optical ground station, serving as a reference source for the wavefront sensor (WFS). In this case, conventional adaptive optics techniques can be directly applied to mitigate atmospheric disturbances affecting the laser downlinks. However, ground-to-space communications (uplinks) present a more significant scientific and technological challenge.

The paper is structured in the following manner: first, the basics of uplink pre-compensation using adaptive optics are explained, along with the associated technical difficulties, some of which have been resolved gradually over time while others remain unanswered. Second, it provides an overview of the timeline of uplink correction in the past 30 years, with an emphasis on current systems under development over the last five years. Additionally, a brief mention is made of uplink correction for deep space missions. Finally, the future prospects of uplink pre-compensation are discussed, including the trade-off between performance gain and the increased complexity of system and operations. This paper focuses solely on reviewing the application of adaptive optics techniques for classical ground-to-space atmospheric pre-compensation, and as such, it does not address downlink correction. The author intentionally chose not to mention quantum communications in the manuscript. It is important to note that AO pre-compensation for quantum uplinks is a relatively nascent area with only a very limited number of publications available.

2. The Uplink Correction Problem

The process of compensating for atmospheric effects in ground-to-space communications differs from the one in the downlink scenario. When transmitting from the ground to a satellite, the motion of the satellite and the finite speed of light require the communication laser to be pointed ahead of the satellite’s current position to establish the link. This pointing angle is referred to as the point-ahead angle, denoted by , where V represents the satellite’s velocity perpendicular to the line of sight, and c represents the speed of light [1].

To ensure optimal signal transmission, adaptive optics (AO) pre-correction of the uplink signal may be necessary. This process involves utilizing an unidentified reference source in the sky to probe the atmospheric turbulence, followed by applying the conjugate of the measured wavefront to the deformable mirror before the signal exits the transmitting telescope.

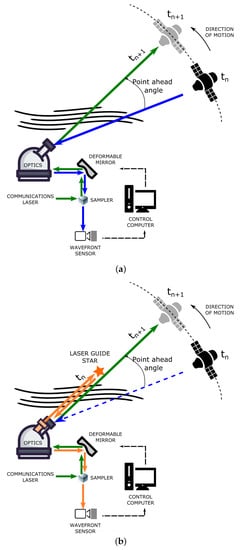

In the context of ground-to-space optical transmission, two configurations can be considered for an AO pre-correction system. One approach involves using the downlink signal transmitted by the satellite itself as the natural light source for the wavefront sensor (Figure 1a). However, due to the presence of a point-ahead angle between the downlink and uplink communication lasers, the level of correction attainable may be restricted by the dynamic nature of the atmosphere, which may differ between the downlink and uplink paths. This limitation is commonly referred to as anisoplanatism. The isoplanatic angle defines a specific angular region in the sky where the correlation between the complex amplitudes of light passing through corresponding angular locations decreases below a predetermined threshold, typically set at 0.5 [2]. According to the definition provided by [3], the isoplanatic angle corresponds to the angular separation at which the root mean square (RMS) phase difference between two points reaches 1 radian. Light waves (i.e., downlink and uplink) that are separated by an angle larger than the isoplanatic angle experience anisoplanatism, where the degree of correlation between their complex amplitudes deteriorates.

Figure 1.

Adaptive optics for ground-to-space optical communications. (a) The downlink/satellite beacon is used as a reference source for the wavefront sensor; (b) a laser guide star is propagated to the uplink expected location and used as a reference source for the wavefront sensor.

A more effective approach involves generating a laser guide star (LGS) precisely at the anticipated uplink location, enabling the measurement and correction of the turbulence through the same atmospheric volume (Figure 1b). However, using artificial stars as probes has limitations in capturing the first modes of the atmospheric turbulence (tip-tilt). Since LGSs are projected upwards into the atmosphere and their light travels downwards towards the telescope, the laser undergoes two deflections along a nearly identical path but in different directions. As a result, the tip and tilt components are effectively compensated, leading to the formation of a quasi-stable LGS image in the focal plane of the telescope. This is known as the tip–tilt indetermination problem [4]. Consequently, the wavefront sensor detector is unable to detect the tip–tilt signal, rendering it blind to these atmospheric modes. This necessitates the inclusion of a natural guide star. To overcome this challenge, a combination of measuring these modes using the downlink signal transmitted by the satellite and the laser guide star to capture the remaining turbulence can be employed. However, it is crucial to consider the point-ahead angle between the downlink and uplink communication lasers once again, as it may impact the achievable level of correction when measuring the atmospheric tip–tilt during the downlink phase.

It is important to highlight that adaptive optics (AO) is extensively employed in the field of astronomy to mitigate the adverse effects of atmospheric turbulence on astronomical observations. Astronomical observatories are meticulously chosen based on thorough testing to identify sites with remarkably favorable turbulence conditions. These carefully selected locations help optimize the performance of the AO system. In contrast, when considering the application of AO in optical communications, a distinct set of challenges arises. The ground terminals for optical communications are typically distributed across various locations, leading to a more diverse range of atmospheric turbulence conditions. Unlike astronomical observatories, which are strategically positioned, optical ground stations may encounter stronger turbulence due to their wider geographical spread. Consequently, an AO system implemented in optical communications must be specifically designed to cope with these varying and more challenging turbulence conditions.

Overcoming the absence of a readily available reference source for wavefront sensing is just one of the challenges in ground-to-space AO pre-compensation. Additionally, ensuring continuous operation throughout both day and night presents a unique set of boundary conditions for the AO system. The ever-changing atmosphere, influenced by sunlight heating the ground surface during the day, creates a stronger turbulent layer near the ground. This poses a considerable strain on an AO system originally designed for night-time operation. Consequently, the AO system must not only compensate for the presence of strong turbulence but also demonstrate adaptability to effectively handle the contrasting conditions encountered during day and night scenarios. All of these factors contribute to the interesting challenge of uplink correction.

3. First Studies and Demonstrations

The earliest mention of an adaptive optics system that considered the effect of anisoplanatism and scintillation was in a 1981 report by David L. Fried and Glenn A. Taylor [5]. Their research was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency of the USA Department of Defense and was published in the report “Strategic Laser Communications Uplink Analysis”. In this publication, Fried and Taylor extended the previous propagation theory to account for the effect of anisoplanatism between the two directions of sensing and correction, something directly applicable to the uplink AO pre-compensation.

Fried and Taylor concluded that the expected performance of an AO system for a laser transmitter is heavily affected by two additional contributors that had not been taken into consideration until then: the anisoplanatism term (as explained in the previous section) and what they called the “random apodization term”. The random apodization term refers to the intensity fluctuations caused by atmospheric scintillation, which can lead to a decrease in the amount of light received by the wavefront sensor.

This report laid the foundation for the use of AO in laser communications and paved the way for the subsequent research in this area. The principle of reciprocity, for which the “adaptive optics can apply a correction that corresponds to distorting an undistorted wavefront so that it is appropriately inverse to the reference signals wavefront distortion” [5], has since been widely used in adaptive optics.

The relationship between the fade and surge of an optical signal and the log-amplitude variance of a scintillated spherical wave was investigated by Yura and McKinley in 1983 [6]. Sasiela [7], in a separate contribution, presented a comprehensive methodology for calculating the log-amplitude variance specifically for a beam that undergoes compensation through adaptive optics. Building upon the research by Yura, McKinley, and Sasiela, Robert Tyson made a significant advancement by extending their analyses. Tyson explored the impact of pre-compensating a range of atmospheric modes and its subsequent effect on scintillation and gain on fade and surges in a ground-to-space optical link [8]. The mathematical expressions derived by Tyson have since become a reference for the research community.

The log-amplitude variance on a laser beam can be obtained by integrating the product of the spatial covariance function of the beam and the corresponding filtering functions that accurately depict the compensation achieved through adaptive optics:

where L is the height of the space asset, z is the altitude of the atmospheric layers, k is the two-dimensional spatial frequency, and are filter functions for each of the N Zernike polynomial terms removed by the adaptive optics [8].

By solving the previous equation numerically for Zernike modes up to N = 32, Tyson concluded that the reduction in scintillation follows the relationship:

where N is the number of fully compensated Zernike modes.

However, it is important to note that the complete compensation of modes is not achievable in practice, and the corrections are limited by the presence of anisoplanatic effects and the finite bandwidth of the adaptive optics system. Tyson expressed the effective correction of the mode as [8]:

The isoplanatic error is represented by , where is the angle separating the two paths, and is the isoplanatic angle for a given atmosphere [8]. The servo bandwidth error is represented by , where is the AO system bandwidth, and is the Greenwood frequency [9].

Tyson expanded on the study of intensity variance across the aperture by examining the probability of signal fades and surges at the receiver; the analysis focused on two cases of fades (3 dB and 6 dB, representing 50% and 75% decreases, respectively) and two cases of surges (3 dB and 6 dB, representing and increases in intensity, respectively), and investigated the thereon effect of correcting a number of Zernike modes in the uplink.

Tyson’s analysis revealed that implementing a ground-based AO system with more than 50 actuators distributed across the pupil could reduce the fade of the GEO uplink signal by a factor of three. This reduction assumes a 0.5 m aperture in both the ground and space segments, with a wavelength of 1550 nm. It is important to note that without accounting for the impact of anisoplanatism (which can be addressed by measuring the wavefront at the uplink location using a laser guide star), the AO system already demonstrates significant improvement by removing only 11 modes. Additionally, Tyson concluded that correcting 30 modes further reduces the average duration of signal fade by over four-fold. These findings highlight the significance of mitigating the effect of anisoplanatism through the use of a beacon directed towards the uplink location prior to transmission.

In 1996, the Japanese Communications Research Laboratory (currently known as National Institute of Information and Communications Technology-NICT) announced their intentions to launch an innovative program that would enable advanced communications through the atmosphere with AO pre-compensation [10,11]. The primary objective of the program was to establish a high-speed optical feeder link at 1.5 μm wavelength with a data rate of up to 10 Gbps between a ground station and a GEO satellite within a decade. Unfortunately, the program was terminated in 2006 due to budgetary constraints [12]. The AO system was planned to be used for an optical feeder link, included a 13-electrode bimorph deformable mirror and a Shack–Hartmann wavefront sensor. The primary goal of this bi-directional AO system was to correct the downlink and enhance its coupling efficiency into a single-mode fiber, as well as pre-compensate the feeder link using the same downlink signal with the wavefront sensor. The proposed system was a remarkable breakthrough at the time as it was the first AO system specifically designed for both downlink correction and pre-compensation of the uplink.

In the early 2000s, Tyson expanded his studies on scintillation and the effects of correcting some atmospheric modes and related them to the bit error rate (BER) [13]. The BER is defined as the probability of a bit error assuming a Gaussian distribution of the noise [1]:

where is the complementary error function, is the instantaneous signal current, and is the standard deviation of the noise, which Tyson carefully related to the scintillation and the adaptive optics correction by calculating the intensity variance on the communications uplink. This study builds upon the analysis of the BER as a function of the Zernike modes corrected by the adaptive optics (AO) system, and arrives at a similar conclusion: the removal of as few as ten Zernike modes can significantly increase the BER on the uplink and result in reductions from to at 30 elevation above the horizon. It should be noted that in this analysis, Tyson did not consider the effects of isoplanatic errors nor the limited control bandwidth of the AO system.

Simultaneously to Tyson’s research, the concept of two-deformable mirror full pre-compensation was first mentioned in the framework of achieving full-wave compensation (phase and amplitude) on horizontal laser beam transmission [14]. This technique involves the use of two deformable mirrors to compensate for both phase and amplitude distortions of the transmitted beam. While the focus of that publication is on horizontal beam propagation, its relevance to upward propagation cannot be overlooked, especially regarding pre-compensation considerations. It is important to note that AO systems for uplink correction are required to operate at very low elevation angles to ensure continuous operations. Therefore, advancements in horizontal beam pre-compensation are applicable to the field of uplink correction. Barchers and Fried analyzed via numerical simulations the performance of full-wave vs. phase-only correction on the horizontal beam. Specifically, it was concluded that the use of a phase-only system in the simulated horizontal beam propagation resulted in a maximum Strehl ratio of 0.8 (for ). However, the implementation of the full-wave compensation technique achieved a nearly perfect Strehl ratio of 1. In the aforementioned manuscript, D represented the diameter of the telescope, and , the Fresnel length being , the wavelength, and L, the total propagation length.

In 2016, the pioneering studies conducted by Tyson were further expanded to explore the relationship between optical ground stations located at different altitudes and feeder links to a GEO satellite [15]. The objective was to analyze the link budget and investigate the potential gain in the link margin due to the pre-compensation of the feeder link through AO techniques, in conjunction with packet-level coding, which is not covered in this article. The study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of AO uplink correction in enhancing the performance of feeder links from ground stations situated at various elevations (300 m, 900 m and 1500 m above sea level). The findings revealed that the application of AO pre-compensation would significantly enhance the link margin for ground stations located at 300 m and 900 m above sea level; in these scenarios, without AO, the link would not be established. To the contrary, for ground stations located at a higher altitude of 1500 m above sea level, the addition of packet-level coding alone would be sufficient to close the link, obviating the need for AO correction. This study represents one of the initial references to the trade-off between the advantages/gain of AO pre-compensation vs. the complexity of the system that could be simply removed by changing the location of the ground transmitter.

The first publications describing dedicated test benches and laboratory demonstrations to explore the advantages of uplink correction started appearing in 2016. A laboratory simulation on the effect of the point-ahead angle at the Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Optics and Precision Engineering [16] was one of the first breadboards to investigate the effect of uplink pre-compensation. The setup emulated a bidirectional link with ALPHASAT from the 1-m ESA Optical Ground Station with an AO system pre-compensating the uplink using the downlink as a reference source for the wavefront sensor. Results from this breadboard experiment indicated that without atmospheric pre-compensation, only 3% of the data points would exhibit beam wander, resulting in the GEO satellite receiving at least 50% of the maximum irradiance.However, with pre-compensation, percentages of 73% () and 66% () were achieved, corresponding to the most and least favorable case of emulated wind direction, respectively.

Over the course of the last half-decade, there has been a significant emergence of uplink AO pre-compensation modeling [17,18,19,20,21], feasibility studies, laboratory experiments, and first free-space demonstrations outdoors.

The years 2018 and 2019 witnessed the pioneering execution of the first reported outdoor demonstrations on uplink correction. An experiment known as the Optical Feeder Link Adaptive Optics (OFELIA) was conducted by the Dutch organization TNO (Toegepast Natuurwetenschappelijk Onderzoek) and the German Aerospace Centre DLR (Deutsches Zentrum fur Luft- und Raumfahrt) [22] with the aim of evaluating the effects of pre-compensation using AO and the point ahead angle on a 10 km link with a 300 m altitude difference between the transmitter and receiver. The research team measured the scintillation index and mean irradiance at the receiver for various configurations of corrected atmospheric modes. The findings revealed that the AO technology effectively enhanced the mean irradiance by a remarkable factor of 2.5. Additionally, it significantly reduced the scintillation index by a factor of 4.4 when emulating the point-ahead angle representative of a GEO-link scenario. In 2019, ONERA demonstrated a 13 km pre-corrected link with 1 km altitude difference (the FEEDELIO experiment [23]). The objective of this experiment was to validate the accuracy of the existing numerical simulation tools by comparing them with the experimental results. It was observed that the simulation model showed a high level of agreement in turbulence scenarios with small Rytov numbers, and it was less accurate when the scintillation effects became more pronounced. This disparity between the models and the experimental observations highlights the significance of incorporating an effective modeling approach for scintillation in the simulation tools for ground-to-space propagation through the atmosphere.

4. Current Adaptive Optics Developments for Uplink Correction

4.1. NICT Spatial Optical Communication Device

The Japanese National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT) has recently developed a patent for an innovative compensation optical system capable of selecting the transmission path for the light wave Tx while considering the point-ahead angle [24]. The proposed system incorporates a reflective element in which a portion of the Rx signal is reflected outside the telescope by a deformable mirror (DM) and subsequently measured. As a result, the Rx signal encompasses both the downlink itself and a segment of the propagation path for the uplink. This system comprises two wavefront sensors (WFS) and two DMs. One WFS-DM pair is responsible for correcting the downlink, while the other WFS-DM pair pre-compensates the uplink and a section of the downlink.

4.2. ESA Optical Ground Station

The European Space Agency, through their program Scylight, has made significant investments in exploring atmospheric pre-compensation strategies for ground-to-space optical links. The ESA Optical Ground Station (OGS), situated at the Teide Observatory in Spain, is a 1-meter telescope that has been utilized for optical communication demonstrations since the early 2000s [25,26]. This section describes the current developments that were recently tested at the ESA OGS or will be in the near future.

4.2.1. ALPHA-UP

ALPHA-UP, a prototype of adaptive optics designed for bidirectional communications, was deployed at the Coudé port of the ESA Optical Ground Station (OGS) [27]. Its primary objective is to enable bi-directional adaptive optics correction for the transmission of data between ALPHASAT and the OGS, both for downlink and uplink communications. To achieve this, it utilizes a shared 22 cm sub-aperture within the 1 m pupil, allowing the transmission and reception of laser beacons to and from ALPHASAT through the Coudé path of the OGS. To ensure an effective performance, ALPHA-UP is equipped with a 6 × 6 incoherent Shack–Hartmann wavefront sensor and incorporates spectral filtering, which helps prevent self-blinding resulting from the monostatic configuration.

ALPHA-UP represents a significant milestone as it is, to the best of the author’s knowledge, the first successful demonstration of pre-compensated feeder link correction. By pre-compensating 27 modes of atmospheric turbulence in the uplink communication with ALPHASAT, the ALPHA-UP system achieved an impressive 10 dB improvement in fading statistics compared to using only tip-tilt correction methods. ALPHA-UP is paving the way for uplink pre-compensation, demonstrating the advantages of adaptive optics in operational ground-to-space communications.

4.2.2. ALASCA: Advanced Laser Guide Star Adaptive Optics for Satellite Communication Assessment

The Advanced Laser guide star Adaptive optics for Satellite Communication Assessment (ALASCA) project aims to revolutionize ground-to-space laser communications by leveraging laser guide star adaptive optics (LGS-AO) technology to address the point-ahead problem [28]. It is set to transform the ESA OGS in Tenerife into an optical feeder link (OFL) test facility with a target technology readiness level (TRL) of 6 and plans for 24/7 operation. TRLs (based on the ISO 16290 standard) are used to assess the maturity level of a technology, ranging from 1 (basic principle) to 9 (deployed and proven to work in an operational environment). ALASCA aims to reach TRL 6, which represents a demonstrator model validating the critical functions of the technology in the relevant environment. Advancing to TRL 7 and beyond involves transitioning from a test bench demonstrator to a final functioning instrument that can be operated by the ground station personnel with basic knowledge of the system.

To achieve this, ALASCA builds upon the existing CaNaPy test bench, originally designed for night-time astronomical observations [29]. The CaNaPy system features a remarkable 70+ W 589 nm laser, currently unmatched in its capabilities. While most astronomical AO systems utilize a 20 W 589 nm laser, the higher power of the CaNaPy laser produces a brighter laser guide star to enhance the performance of the adaptive optics system during both day and night operations. ALASCA will expand the CaNaPy facility capability by upgrading both its hardware and software to specifically cater to the development of ground-satellite optical communication.

The daytime operation of a LGS-AO has been noted in the past as one impediment for LGS-AO being applicable to optical communications. Nonetheless, remarkable strides have been made in overcoming this limitation. The recent experiments have revealed that it is indeed possible to attain equivalent return flux even in daytime scenarios [30,31]. This notable achievement was made possible through the incorporation of ultra-narrow band magneto-optical filters (MOF) within the system configuration. The inclusion of this filter plays a crucial role in reducing the daytime bright background, with a 100,000:1 extinction ratio while maintaining an intrinsic throughput of 97% [31].

ALASCA marks a significant milestone as a pioneering system at TRL6, which leverages laser guide star adaptive optics as the optimal solution for uplink pre-compensation.

4.2.3. Coudé Laser Communications System

The Coudé Laser Communications System (CLCS) is part of the ESA OGS upgrades [32,33]. The CLCS is an adaptive optics system for bi-directional links incorporating atmospheric correction in both the downlink and uplink. In the receive direction of the optical system, the entire 1m aperture of the telescope is used to capture the incoming signal. In the transmit direction, the OGS telescope aperture is divided into quadrants, and a 20 cm beam is transmitted from each quadrant. The CLCS also incorporates various techniques to enhance the overall performance, including wavelength multiplexing, spatial diversity, and pre-compensation for each transmitted beam.

4.3. FEELINGS: FEEder LINks Optical Ground Station and VERTIGO Experiment

FEEder LINks optical Ground Station (FEELINGS) is ONERA’s current development of a research optical ground station to explore and enhance technological advancements for both GEO feeder links and LEO links [34]. Notably, one of the key components integrated into FEELINGS is AO pre-compensation. The development of FEELINGS by ONERA is an extension of their previous endeavor, the FEEDELIO experiment. In this pursuit, they conducted the VERTIGO experiment in June and July 2022, serving as a pathfinder for the forthcoming development of FEELINGS.

During the VERTIGO experiment, ONERA successfully demonstrated optical transmission capability over a distance of 53 km while maintaining an elevation of 2 degrees. This remarkable achievement involved data transfer rates exceeding 1 Terabit per second (1 Tb/s) on a single channel [35]. To reach 1 Tbit/s, the link employed a dual polarized 84 GBd 64QAM signal, while the atmospheric turbulence was mitigated by adaptive optics. They showed that the received power distribution improved by 19.5 dB when tip-tilt correction was in place, while it increased by 28.1 dB when full AO was used instead. They also pointed out that in order to achieve a line rate of 1 Tb/s, a full wavefront correction was required in order for the forward error correction threshold of the received power to be above 35.53% on the 84 GBd 64QAM signal, with respect to 7.22% when only tip-tilt was corrected.

4.4. TOmCAT Optical Ground Terminal

The Terabit Optical Communication Adaptive Terminal (TOmCAT) is a current development of an optical ground terminal by TNO, specifically designed for terabit-per-second optical feeder links [36]. This project serves as a continuation of the earlier OFELIA experiment. In this phase of the project, the main objective is to showcase the effectiveness of AO pre-correction technology in a terabit optical ground station during daytime ground-to-ground link field tests. This experiment covered a distance of 10 km, with a significant height difference of 226 m between the terminals. To assess the point-ahead effect on the transmission, various point-angles were tested, ranging from 0 to 29 microradians. The outcomes of the experiments revealed a three-fold gain improvement in relative transmission path losses when pre-correcting 28 atmospheric modes. Furthermore, in conditions of strong turbulence, an average gain of 5 dB was observed compared to solely correcting the tip-tilt.

5. Deep Space Optical Communications and Uplink Correction

The International Telecommunications Union (ITU) defines the boundary for deep space as any region beyond 2 million kilometers from Earth. Transmitting and receiving optical signals over such vast distances presents significant implications and necessitates a completely novel set of considerations for ground-to-space communications. Transmitting lasers from the ground to deep-space terminals serves two key functions: acting as a beacon for acquisition, tracking and pointing and facilitating the transmission of uplink and data signal; due to the very faint signals, large telescopes on the ground are a requirement to receive and collect deep-space downlink photons and enable the uplink in the first instance.

The deep-space spacecraft observed from ground terminals on Earth exhibit significantly higher transverse velocities compared to near-Earth spacecraft [37]. This difference in transverse velocities leads to a much larger point-ahead angle. For example, a communications link with Mars could have a point-ahead angle of up to 387 rad [37], whereas the corresponding point-ahead angle for near-Earth spacecraft typically ranges from 20 to 50 rad. The anisoplanatism between the downlink and uplink in this scenario poses a significant challenge for uplink pre-compensation in deep space. Resolving this issue would require laser guide stars to be capable of sensing and retrieving all atmospheric modes, including tip-tilt. However, the tip-tilt indetermination problem on LGS is yet to be solved.

Another unique characteristic of deep-space links is the longer continuous durations at near-Sun angles. In the case of a communications link with Mars, Earth and Mars are both orbiting the Sun at different rates, resulting in a regular variation in the angle between them. At certain points in the Martian year, the Sun–Earth–Probe angle can be less than 90 for most of the Earth year, causing Mars to be in the daytime Earth sky more often than in the night-time sky. As a consequence, both space and ground terminals have to communicate with a small angular separation to the Sun near-superior conjunction.

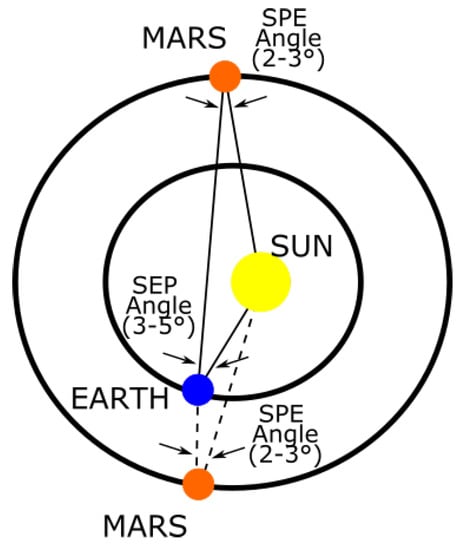

The Sun–Earth–Probe (SEP) and Sun–Probe–Earth (SPE) angles play a critical role in determining the duration and quality of deep-space communication links. The SEP angle is the angle between the Sun and the Earth as seen from the deep-space probe, while the SPE angle is the angle between the Sun and the ground terminal as seen from the deep-space probe. Figure 2 provides an illustration of the Sun–Earth–Probe and Sun–Probe–Earth angles. During superior conjunction, both SEP and SPE angles are small; in contrast, during inferior conjunction, when the SPE angle is small, the SEP angle is larger. In this scenario, the ground terminal would be operating during night-time, while the space terminal is pointing towards the Sun. For link outages less than 1–4 weeks, SEP angles as low as 3–5 and SPE angles of 2–4 are required [38]. Aiming for 24/7 optical communications to deep space terminals would require pointing both space and ground terminals towards the Sun for extended periods.

Figure 2.

Sun–Earth–Probe (SEP) and Sun–Probe–Earth (SPE) angles. During superior conjunction, both SEP and SPE angles are small; in contrast, during inferior conjunction, when the SPE angle is small, the SEP angle is larger. This figure was adapted from [38].

In their 2021 patent, Sakamoto proposed an innovative solution for compensating atmospheric aberrations in a ground-to-Moon communication link [39]. The proposed approach involves the use of two stations on the lunar surface, with one station emitting a “reference light” while the other acts as the receiver. Due to the angular displacement between the Earth’s surface and the Moon, the reference light station is positioned at a specific distance from the receiving station on the lunar surface. This distance corresponds to the round-trip time of 2.53 s, considering the orbital speed of the Moon (1053 m/s), which equates to approximately 2.59 km on the lunar surface. It is important to note that the round-trip propagation time varies as the distance between the Earth and the Moon changes. Consequently, the distance covered by the Moon during the round-trip propagation time also continuously changes. In this context, it is typically assumed that the distance remains constant, leading to a decrease in signal reception level based on the time zone. To address this challenge, the patent introduces a method to virtually alter the transmission point of the reference light by employing a triangular arrangement comprising three reference light stations. This innovative approach enhances the stability and reliability of the ground-to-Moon communication link, enabling efficient compensation for atmospheric distortions in a scenario with a very large point-ahead angle.

In a broader context, a similar approach could be applied by utilizing a satellite constellation in flight formation. In this scenario, the uplink to one satellite could leverage the downlink signal from another satellite as a reference source for its uplink pre-compensation. However, the required proximity to one another based on the point-ahead angle must be studied.

6. Present Challenges and Future Outlook

The performance of uplink communication systems is severely impacted by atmospheric turbulence. While increasing the power of the transmission may be a possible mitigation option, there is a limit to this approach due to non-linear effects with very high power lasers, still to be fully investigated in the context of optical communications. In conditions of strong turbulence, the atmospheric effects may render it impossible to establish a reliable link in the first place. Techniques such as using multiple apertures in the transmitter, combined with higher power, still perform less effectively than using adaptive optics for turbulence mitigation [40].

Pre-compensation with adaptive optics represents a significant advancement in improving the performance of uplink communication systems. By mitigating the effects of atmospheric turbulence, AO enhances the quality of the transmitted signal and enables higher data bandwidth. However, the development and implementation of AO systems can be intricate and expensive, leading to questions about their necessity in certain applications. The primary source of error in AO systems is anisoplanatism, which refers to the variation in optical path distortion across the field of view. To address this issue, laser guide star AO (LGS-AO) techniques were investigated [2,3]. LGS-AO utilizes a laser-generated artificial guide star to probe the atmospheric distortion at the uplink location, facilitating a more accurate correction than the one provided by sensing the wavefront on the downlink. Nevertheless, there are still technical challenges associated with LGS-AO, particularly concerning the tip-tilt indetermination problem, which refers to the difficulty of precisely measuring and correcting low-frequency atmospheric disturbances on artificial stars [4].

Developing LGS-AO systems for communication purposes requires a multidisciplinary team of experts; the technology is currently at relatively low TRLs in this context, indicating that further research and development are needed to mature the systems for practical deployment in the field of optical communications.

However, considerable progress has been made on AO and LGS-AO systems over the past decade, paving the way for simplification in the near future. There are several potential pathways for cost and complexity reduction in adaptive optics uplink correction. These could include the development of more affordable guide star laser systems and the consideration of different laser technologies. Additionally, incorporating the guidelines and best practices specifically designed for AO systems in the context of uplink pre-compensation could streamline the design and implementation processes. Finally, the integration of robotic AO systems that would require minimal supervision and engineering time could also contribute to simpler systems. These future actions could be avenues to cost and complexity reduction, facilitating a more widespread adoption of AO pre-compensation in ground-to-space communication links.

Funding

This research has been funded through the ANU Futures Scheme 2.0 Grant by the Australian National University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the fruitful conversations with colleagues in the adaptive optics and telecommunications communities. Particularly noteworthy were the engaging conversations during the Communications and Observations through Atmospheric Turbulence (COAT23) workshop, expertly hosted and organized by Durham University. Furthermore, the author acknowledges the productive exchanges with fellow professionals at the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology in Japan, the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the European Space Agency, which greatly contributed to the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALASCA | Advanced Laser guide star Adaptive optics for Satellite Communication Assessment |

| AO | Adaptive optics |

| BER | Bit error rate |

| CLCS | Coudé laser communications system |

| DLR | Deutsches Zentrum fur Luft- und Raumfahrt |

| DM | Deformable mirror |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| FEELINGS | FEEder LINks optical Ground Station |

| ITU | International Telecommunications Union |

| LGS | Laser guide star |

| MOF | Magneto-optical filters |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NICT | National Institute of Information and Communications Technology |

| OFELIA | Optical feeder link adaptive optics |

| OFL | Optical feeder link |

| OGS | Optical ground station |

| SEP | Sun–Earth–Probe |

| SPE | Sun–Probe–Earth |

| TNO | Toegepast Natuurwetenschappelijk Onderzoek |

| TOmCAT | Terabit Optical Communication Adaptive Terminal |

| TRL | Technology readiness level |

| WFS | Wavefront sensor |

References

- Andrews, L.C.; Phillips, R.L. Laser Beam Propagation through Random Media; SPIE Press Book: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1988; ISBN 9781510643703. [Google Scholar]

- McKechnie, T.S. General Theory of Light Propagation and Imaging Through the Atmosphere; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 196, pp. 1–624. [Google Scholar]

- Glindemann, A. Principles of Stellar Interferometry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-642-15028-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut, F.; Gendron, E. Laser guide star in adaptive optics: The tilt determination problem. Astron. Astrophys. 1992, 261, 677–684. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, D.L.; Tyler, G.A. Strategic Laser Communications Uplink Analysis; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 1981.

- Yura, H.T.; McKinley, W.G. Optical scintillation statistics for IR ground-to-space laser communication systems. Appl. Opt. 1983, 22, 3353–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasiela, R.J. A Unified Approach to Electromagnetic Wave Propagation in Turbulence and the Evaluation of Multiparameter Integrals; MIT Lincoln Laboratory Report 807; 1MIT Lincoln Laboratory: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson, R.K. Adaptive optics and ground-to-space laser communications. Appl. Opt. 1996, 35, 3640–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, G.A. Bandwidth considerations for tracking through turbulence. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 11 1994, 358–367, 119942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimoto, Y.; Hayano, Y.; Klaus, W. High-speed optical feeder-link system using adaptive optics. In Proceedings of the SPIE 2990, Free-Space Laser Communication Technologies IX, San Jose, CA, USA, 24 April 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hayano, Y.; Arimoto, Y.; Klaus, W. Ground-to-satellite laser communication program at CRL using adaptive optics. In Proceedings of the SPIE 3126, Adaptive Optics and Applications, San Diego, CA, USA, 17 October 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinori, A. Study on Laser Communications Demonstration Equipment at the International Space Station. J. Natl. Inst. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2004, 51, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson, R.K. Bit-error rate for free-space adaptive optics laser communications. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2002, 19, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchers, J.D.; Fried, D.L. Optimal control of laser beams for propagation through a turbulent medium. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image. Sci. Vis. 2002, 19, 1779–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, S.; Matuz, B.; Liva, G.; Barrios, R.; Calvo, R.M.; Giggenbach, D. Digital Modulation and Coding for Satellite Optical Feeder Links with Pre-distortion Adaptive Optics. Int. J. Satell. Commun. Netw. 2016, 34, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhard, N.; Berlich, R.; Minardi, S.; Barth, A.; Mauch, S.; Mocci, J.; Goy, M.; Appelfelder, M.; Beckert, E.; Reinlein, C. Real-time adaptive optics testbed to investigate point-ahead angle in pre-compensation of Earth-to-GEO optical communication. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 13157–13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, N.; Rodríguez-Ramos, L.F.; Sodnik, Z. Toward the uplink correction: Application of adaptive optics techniques on free-space optical communications through the atmosphere. Opt. Eng. 2018, 57, 076106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, J.; Townson, M.J.; Farley, O.J.D.; Reeves, A.; Calvo, R.M. Adaptive Optics pre-compensated laser uplink to LEO and GEO. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 6113–6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidick, E.; Robert, L.C., Jr.; Vilnrotter, V.A.; Marchen, L. Simulations of uplink precompensation for laser communications. In Proceedings of the SPIE 12237, Laser Communication and Propagation through the Atmosphere and Oceans XI, 1223709, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gladysz, S.; Zepp, A.; Bellossi, R.; Segel, M.; McDonald, D.; Stein, K. Adaptive optics for daytime deep-space optical communications. In Proceedings of the SPIE 12237, Laser Communication and Propagation through the Atmosphere and Oceans XI, 1223703, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S.; Schediwy, S. Adaptive optics LEO uplink pre-compensation with finite spatial modes. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saathof, R.; den Breeje, R.; Klop, W.; Doelman, N.; Moens, T.; Gruber, M.; Russchenberg, T.; Pettazzi, F.; Human, J.; Calvo, R.M.; et al. Real-time adaptive optics testbed to investigate point-ahead angle in pre-compensation of Earth-to-GEO optical communication. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Space Optics—ICSO 2018, Chania, Greece, 9–12 October 2018; p. 111802D. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefois, A.M.; Conan, J.-M.; Petit, C.; Lim, C.B.; Michau, V.; Meimon, S.; Perrault, P.; Mendez, F.; Fleury, B.; Montri, J.; et al. Adaptive optics pre-compensation for GEO feeder links: The FEEDELIO experiment. In Proceedings of the SPIE 11180, International Conference on Space Optics—ICSO, Crete, Greece, 9–12 October 2018; p. 111802C. [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima, M.; Dimitat, K. Spatial Optical Communication Device and Method. Japanese Patent JP2018121281A, 18 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, M.; Alonso, A.; Chueca, S.; Fuensalida, J.J.; Sodnik, Z.; Cessa, V.; Bird, A.; Comeron, A.; Rodriguez, A.; Dios, V.F.; et al. Ground-to-space optical communication characterization. In Proceedings of the SPIE 5892, Free-Space Laser Communications V, 589202, San Diego, CA, USA, 12 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Talavera, M.R.; Chueca, S.; Alonso, A.; Viera, T.; Sodnik, Z. Analysis of the preliminary optical links between ARTEMIS and the Optical Ground Station. In Proceedings of the SPIE 4821, Free-Space Laser Communication and Laser Imaging II, Seattle, WA, USA, 9 December 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka, K.; Fischer, E.; Berkefeld, T.; Fischer, C.; Neuweiler, M.; Sodnik, Z.; Voland, C.; Saucke, K.; Seidel, J. Successful First Optical Feeder Link Demonstration between a Ground Station and a GEO Satellite Applying Adaptive Optics Pre- Compensation. COAT23 Conference Presentation. 2023. Available online: https://durhamuniversity-my.sharepoint.com/personal/dbgh26_durham_ac_uk/_layouts/15/onedrive.aspx?ga=1&id=%2Fpersonal%2Fdbgh26%5Fdurham%5Fac%5Fuk%2FDocuments%2FDocuments%2FMeetings%2FCOAT2023%2Fpresentations%2FKudielka%2Epdf&parent=%2Fpersonal%2Fdbgh26%5Fdurham%5Fac%5Fuk%2FDocuments%2FDocuments%2FMeetings%2FCOAT2023%2Fpresentation (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- ALASCA Advanced Laser Guide Star Adaptive Optics for Satellite Communication Assessments. European Space Agency ARTES Program. 2023. Available online: https://artes.esa.int/projects/alasca (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Calia, D.B.; Centrone, M.; Pinna, E.; Alaluf, D.; Martinez, N.; Osborn, J.; Hackenberg, W.; Townson, M.; Faccini, M.; Paola, A.D.; et al. CaNaPy: SatComm LGS-AO experimental platform with laser uplink pre-compensation. In Proceedings of the SPIE 11852, International Conference on Space Optics—ICSO 2020, Virtual, 30 March–2 April 2021; p. 118521A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.; Jefferies, S.M.; Murphy, N. Daylight operation of a sodium laser guide star for adaptive optics wavefront sensing. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2016, 2, 040501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alaluf, D.; Centrone, M.; Calia, D.B.; Suetterling, P.; Speziali, R.; Faccini, M.; Hackenberg, W.; Armengol, J.P.; Paola, A.D. Paving the way to daytime optical feeder links based on LGS assisted adaptive optics. In Proceedings of the SPIE 11852, International Conference on Space Optics—ICSO 2020, Virtual, 30 March–2 April 2021; p. 118525Y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.; Feriencik, M.; Kudielka, K.; Dreischer, T.; Adolph, P.; Berkefeld, T.; Soltau, D.; Kunde, J.; Czichy, R.; Perdigues-Armengol, J.; et al. ESA Optical Ground Station Upgrade with Adaptive Optics for High Data Rate Satellite-to-Ground Links—Test Results. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Space Optical Systems and Applications (ICSOS), Portland, OR, USA, 14–16 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.; Kudielka, K.; Berkefeld, T.; Soltau, D.; Perdigués-Armengol, J.; Sodnik, Z. Adaptive optics upgrades for laser communications to the ESA optical ground station. In Proceedings of the SPIE 11852, International Conference on Space Optics—ICSO 2020, Virtual, 30 March–2 April 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyril, P.; Bonnefois, A.; Conan, J.M.; Durecu, A.; Gustave, F.; Lim, C.; Montri, J.; Paillier, L.; Perrault, P.; Velluet, M.T.; et al. Feelings: The ONERA’s optical ground station for Geo Feeder links demonstration. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Space Optical Systems and Applications (ICSOS), Virtual, 29–31 March 2022; pp. 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitachon, B.I.; Horst, Y.; Kulmer, L.; Blatter, T.; Keller, K.; Bonnefois, A.M.; Conan, J.-M.; Lim, C.; Montri, J.; Perrault, P.; et al. Tbit/s single channel 53 km free-space optical transmission—Assessing the feasibility of optical GEO-satellite feeder links. In Proceedings of the European Conference and Exhibition on Optical Communication 2022, Basel, Switzerland, 18–22 September 2022; Volume hal-03938118. [Google Scholar]

- TOmCAT—Terabit Optical Communication Adaptive Terminal. European Space Agency ARTES Program. 2023. Available online: https://artes.esa.int/projects/tomca (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Boroson, D.M.; Biswas, A.; Edwards, B.L. MLCD: Overview of NASA’s Mars laser communications demonstration system. SPIEV Free-Space Laser Commun. Technol. XVI 2004, 5338, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati, H.; Biswas, A.; Djordjevic, I.B. Deep-Space Optical Communications: Future Perspectives and Applications. IEEE 2011, 99, 2020–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, K.; Katayama, Y.; Yoshizawa, K.; Kinishuta, T.; Yamazaki, E.; Mizuno, T. Optical Wireless Communication System and Optical Wireless Communication Method. International Patent WO2021250895A1, 16 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Conan, J.M.; Bonnefois, A.M. Turbulence Mitigation Strategies for Ground-GEO Uplinks: Adaptive Optics Pre-Compensation on Single Aperture Versus Multi-Aperture Diversity. COAT23 Conference Presentation. 2023. Available online: https://durhamuniversity-my.sharepoint.com/personal/dbgh26_durham_ac_uk/_layouts/15/onedrive.aspx?ga=1&id=%2Fpersonal%2Fdbgh26%5Fdurham%5Fac%5Fuk%2FDocuments%2FDocuments%2FMeetings%2FCOAT2023%2Fpresentations%2FConan%2Epdf&parent=%2Fpersonal%2Fdbgh26%5Fdurham%5Fac%5Fuk%2FDocuments%2FDocuments%2FMeetings%2FCOAT2023%2Fpresentations (accessed on 21 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).