Study of the Feasibility of Using Food-Grade Lactose as a Viable and Economical Alternative for Obtaining High-Purity β-Lactose

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

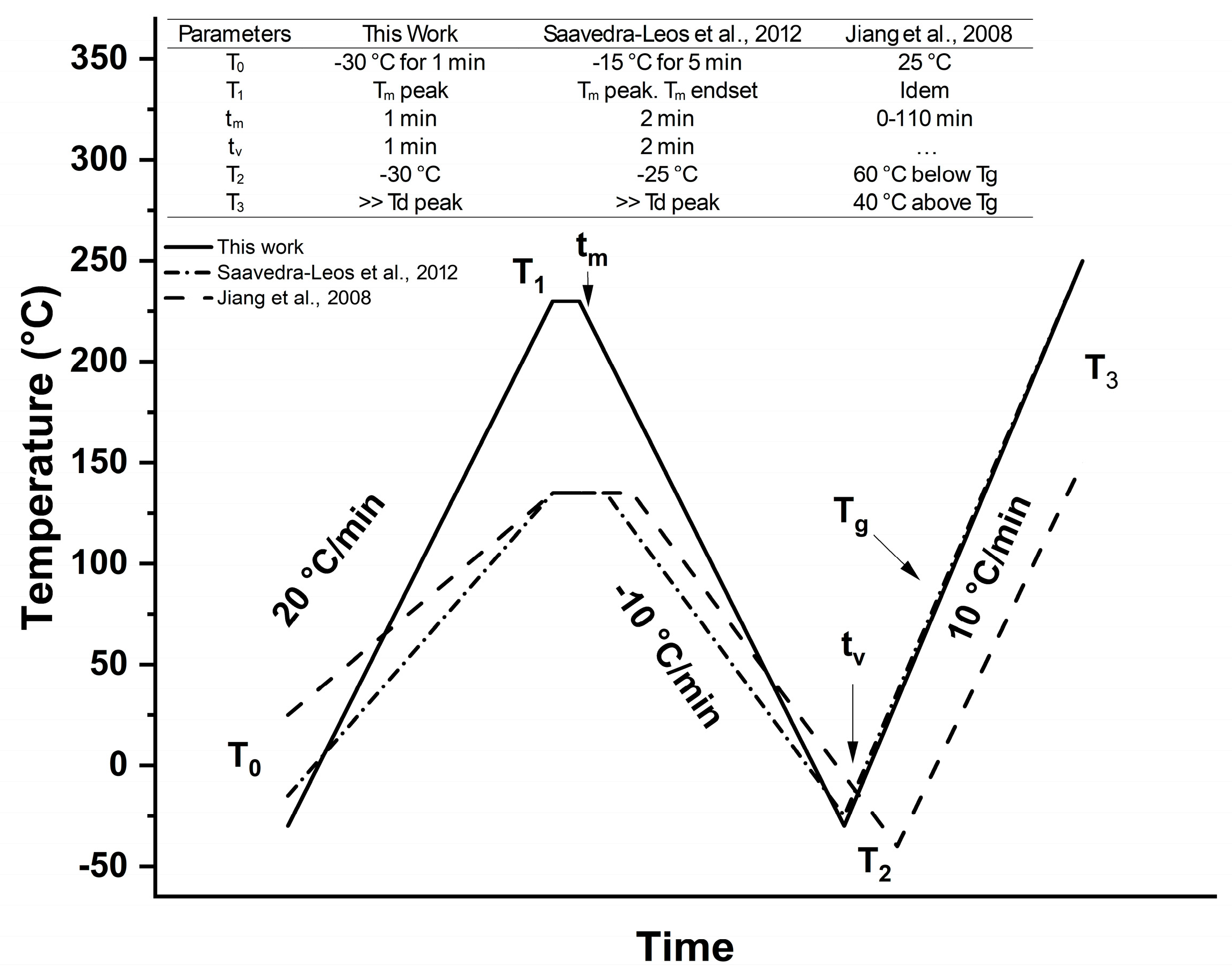

2.2. Interconversion Process of β-Lactose from Food Grade α-Lactose

2.3. Physical Characterization

2.3.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.3.3. Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (MDSC)

2.3.4. Morphological Characterization

2.4. Chemical Characterization

2.4.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.4.2. Raman Spectroscopy

3. Results

3.1. Physical Characterization of Food-Grade α-Lactose

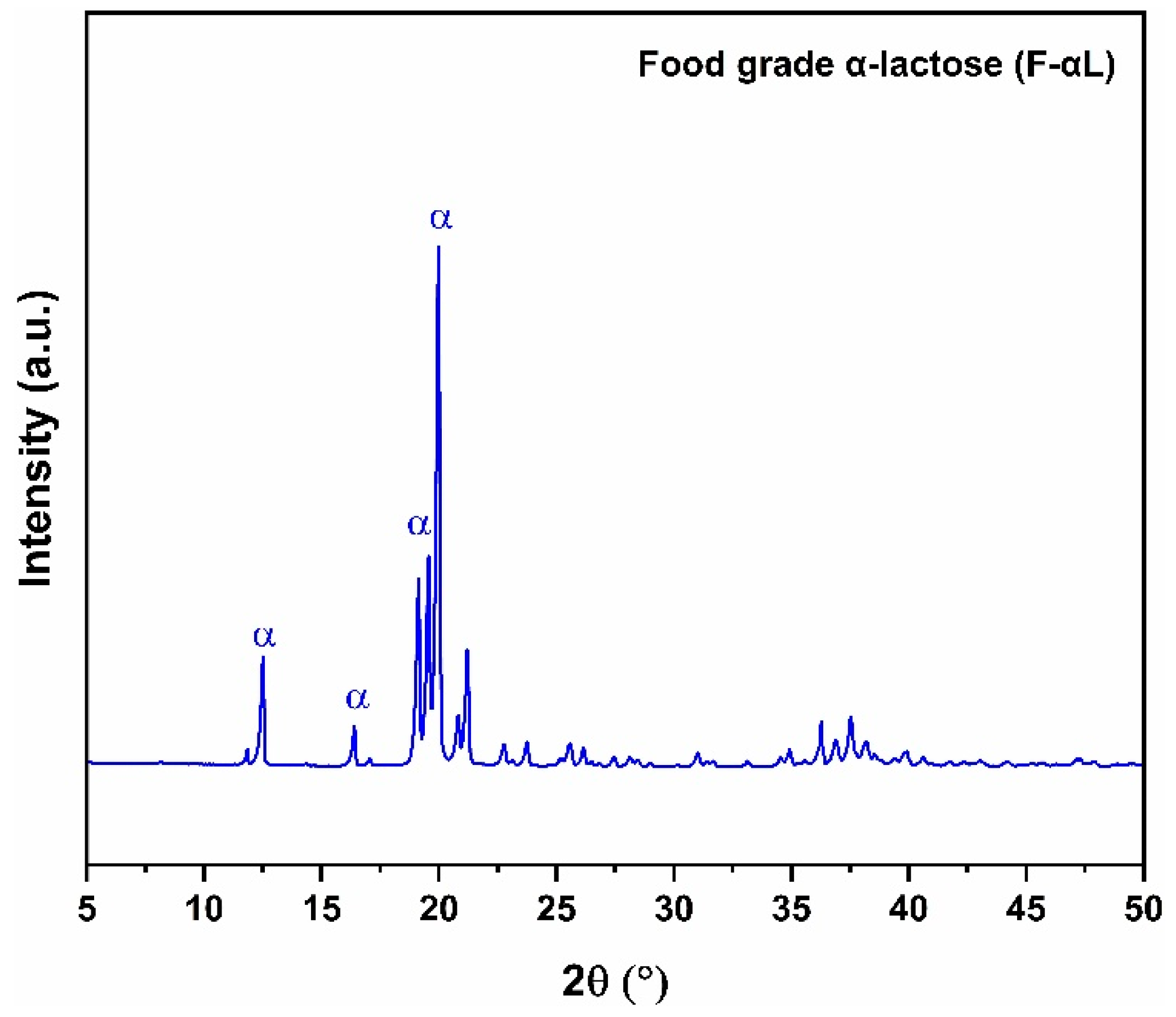

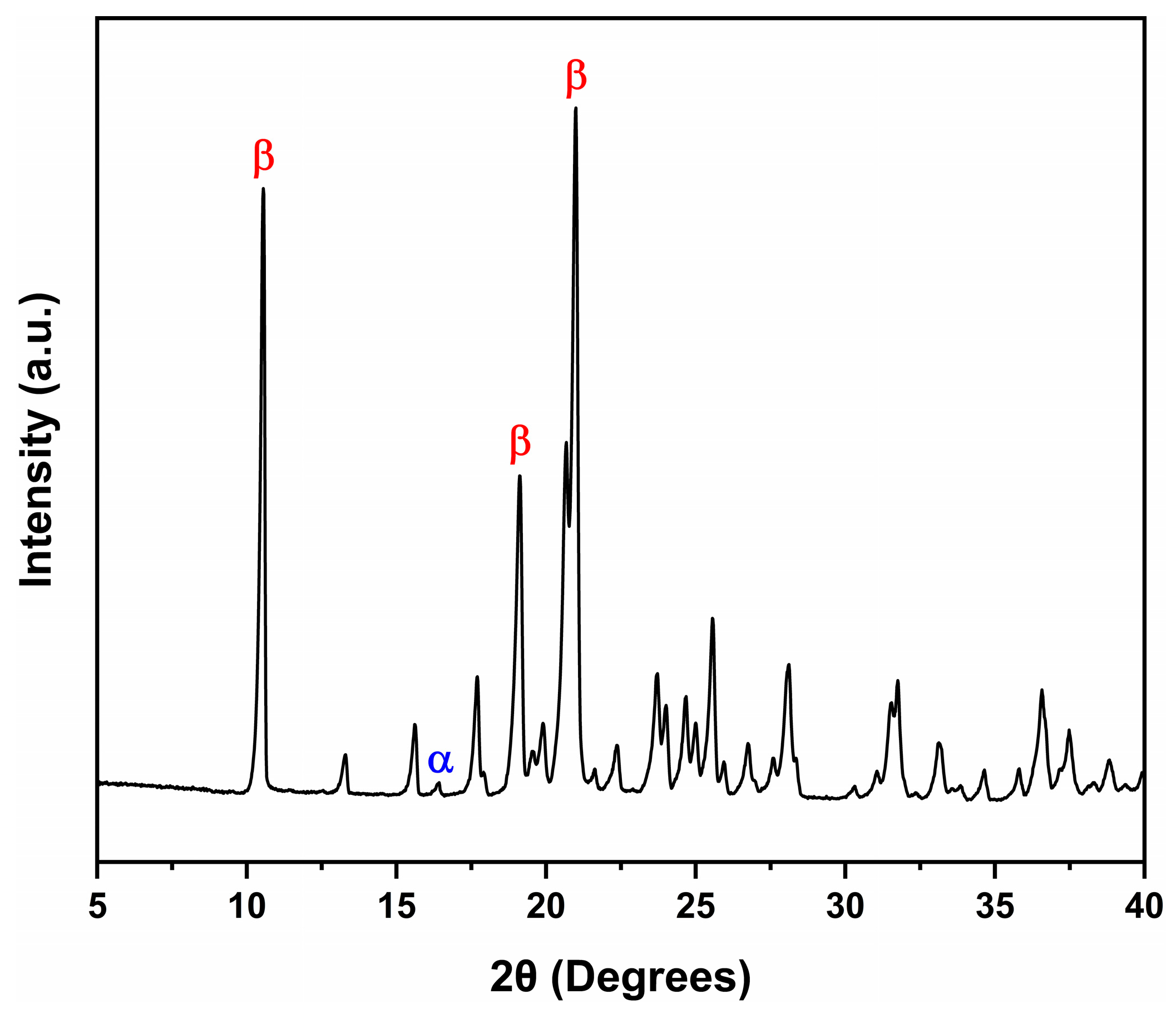

3.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

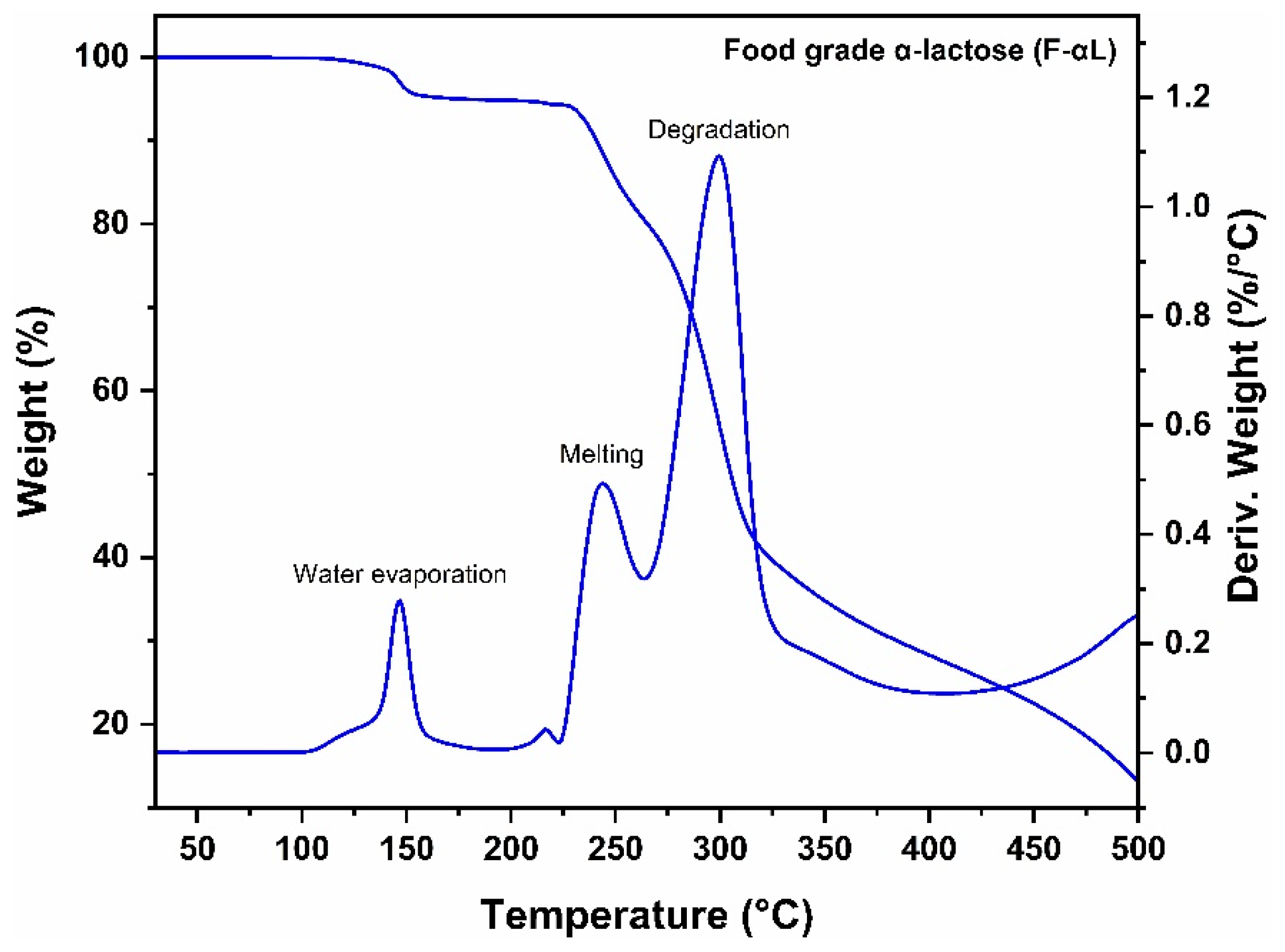

3.1.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

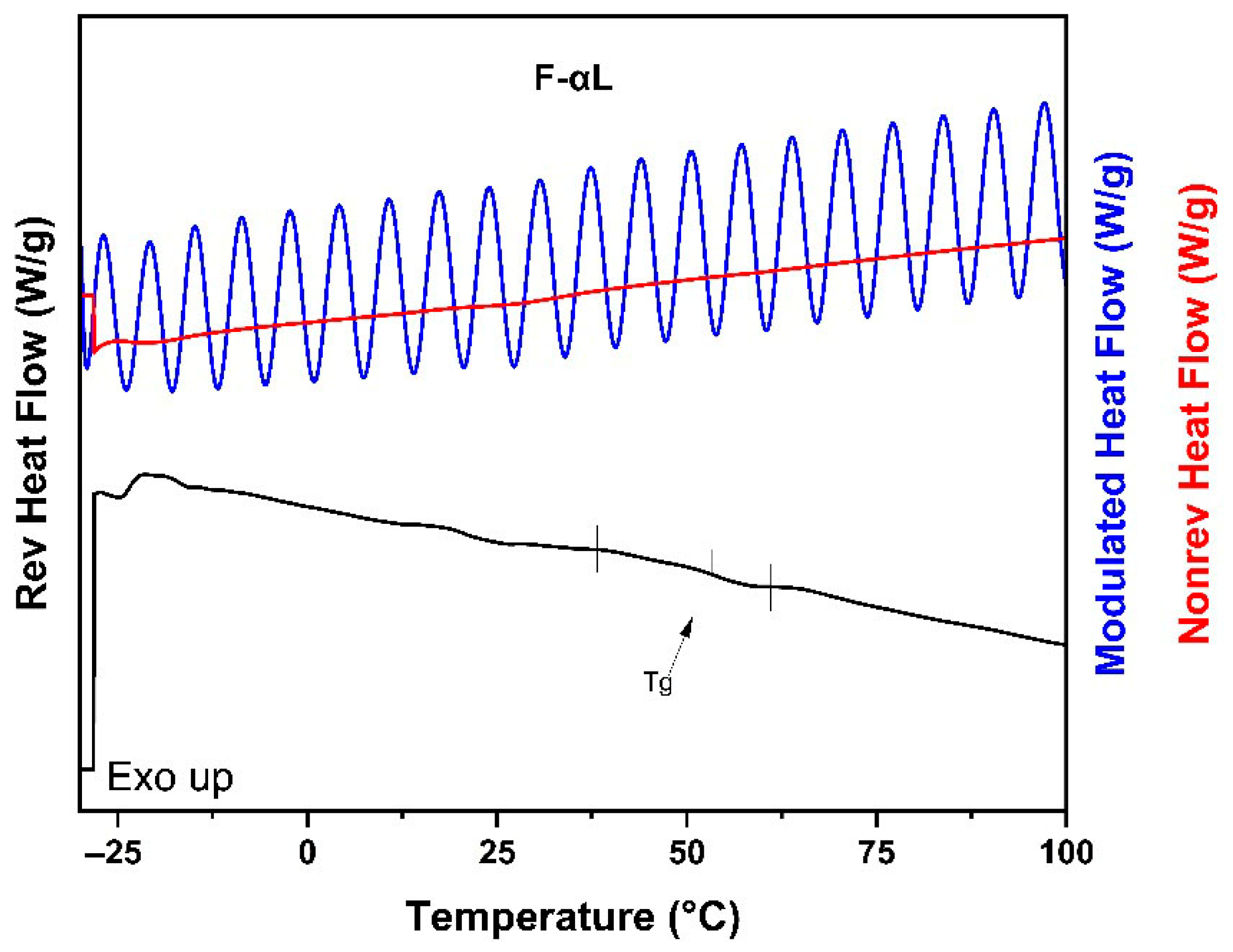

3.1.3. Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (MDSC)

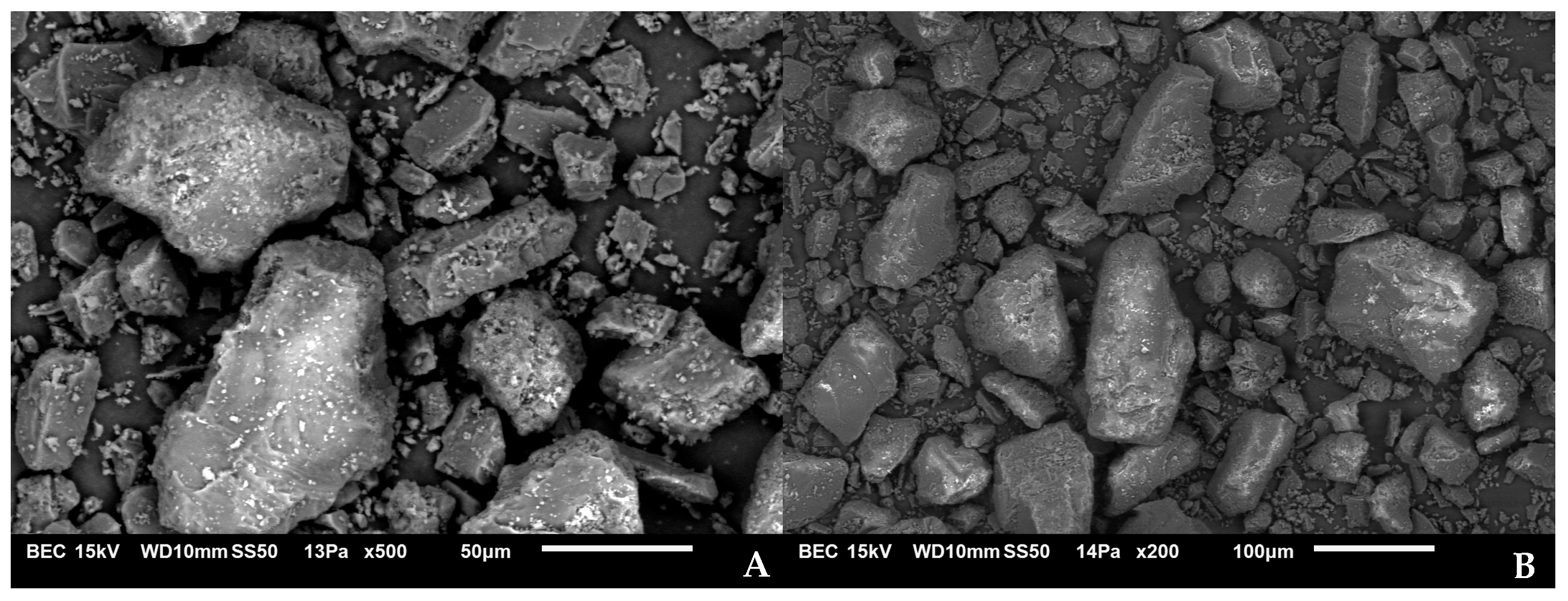

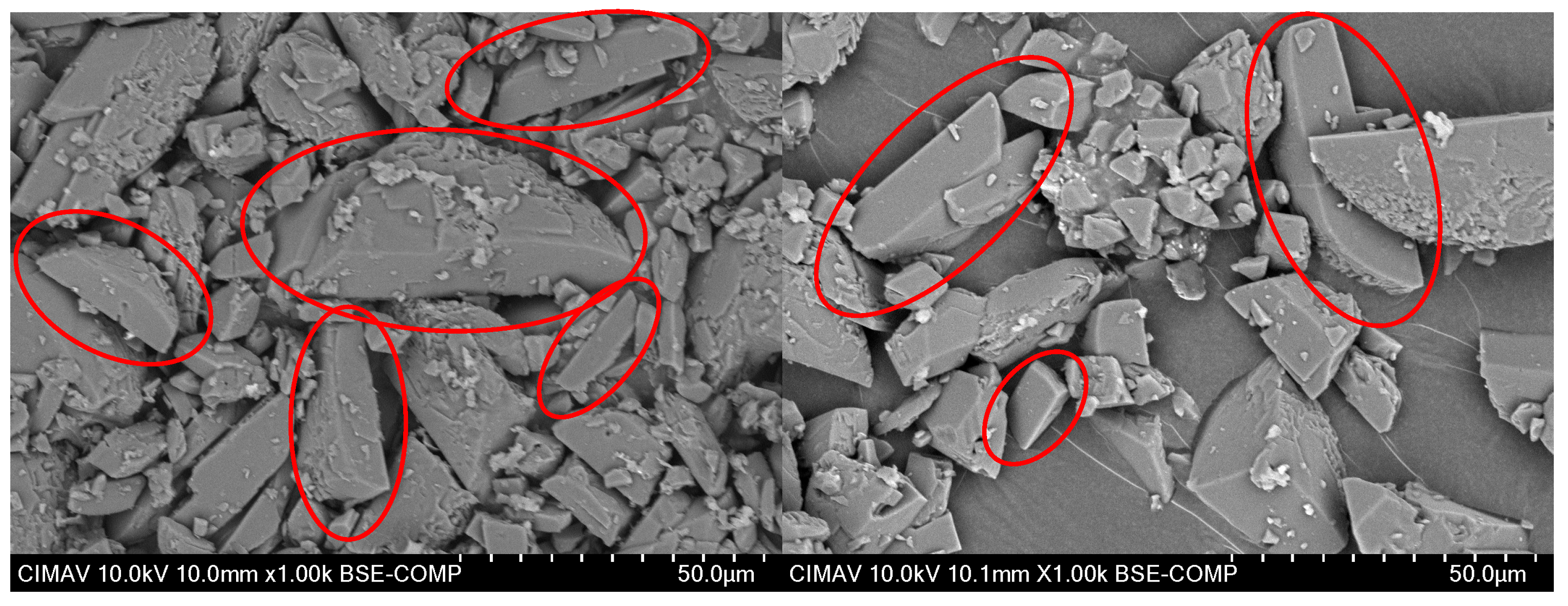

3.1.4. Morphological Characterization

3.2. Chemical Characterization of Food-Grade α-Lactose

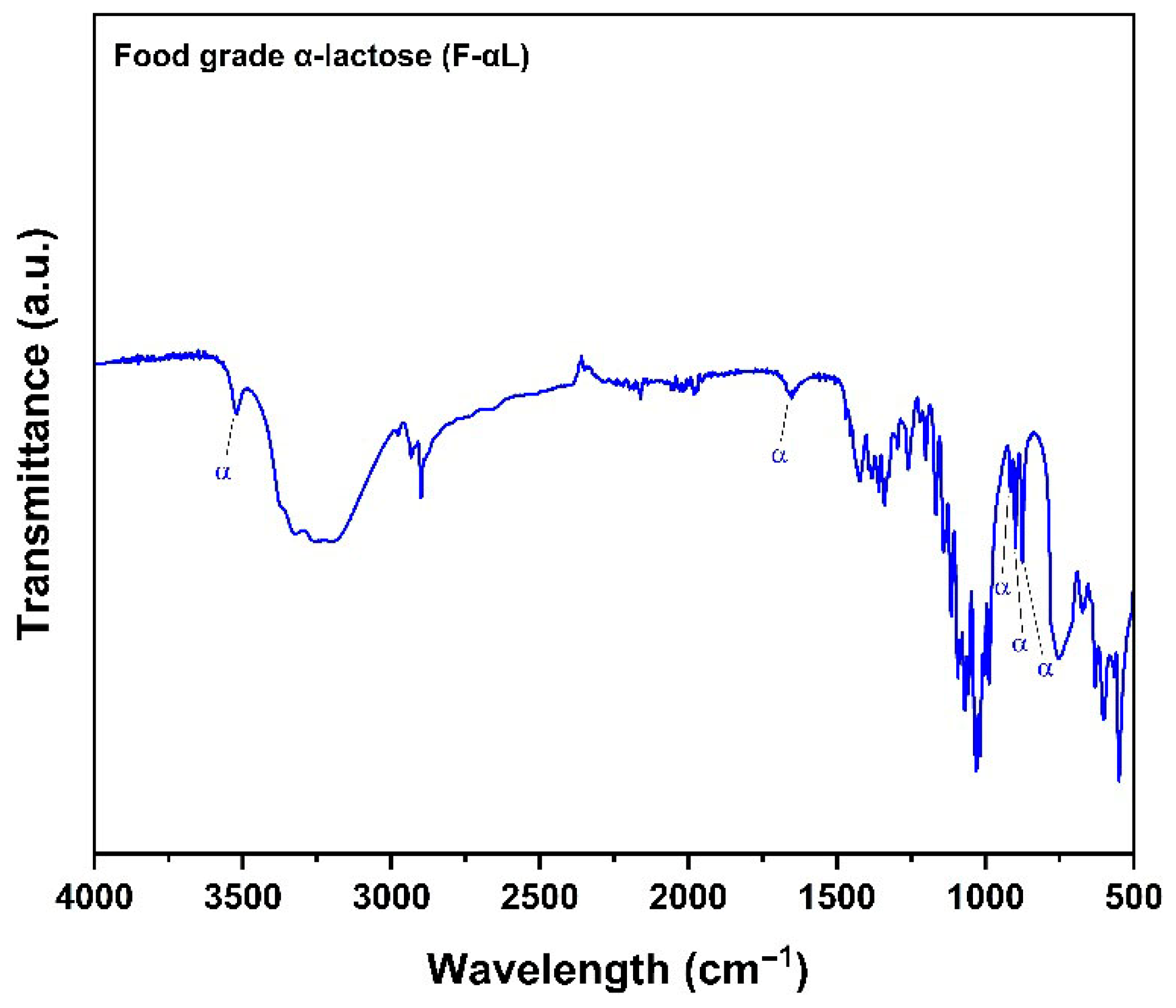

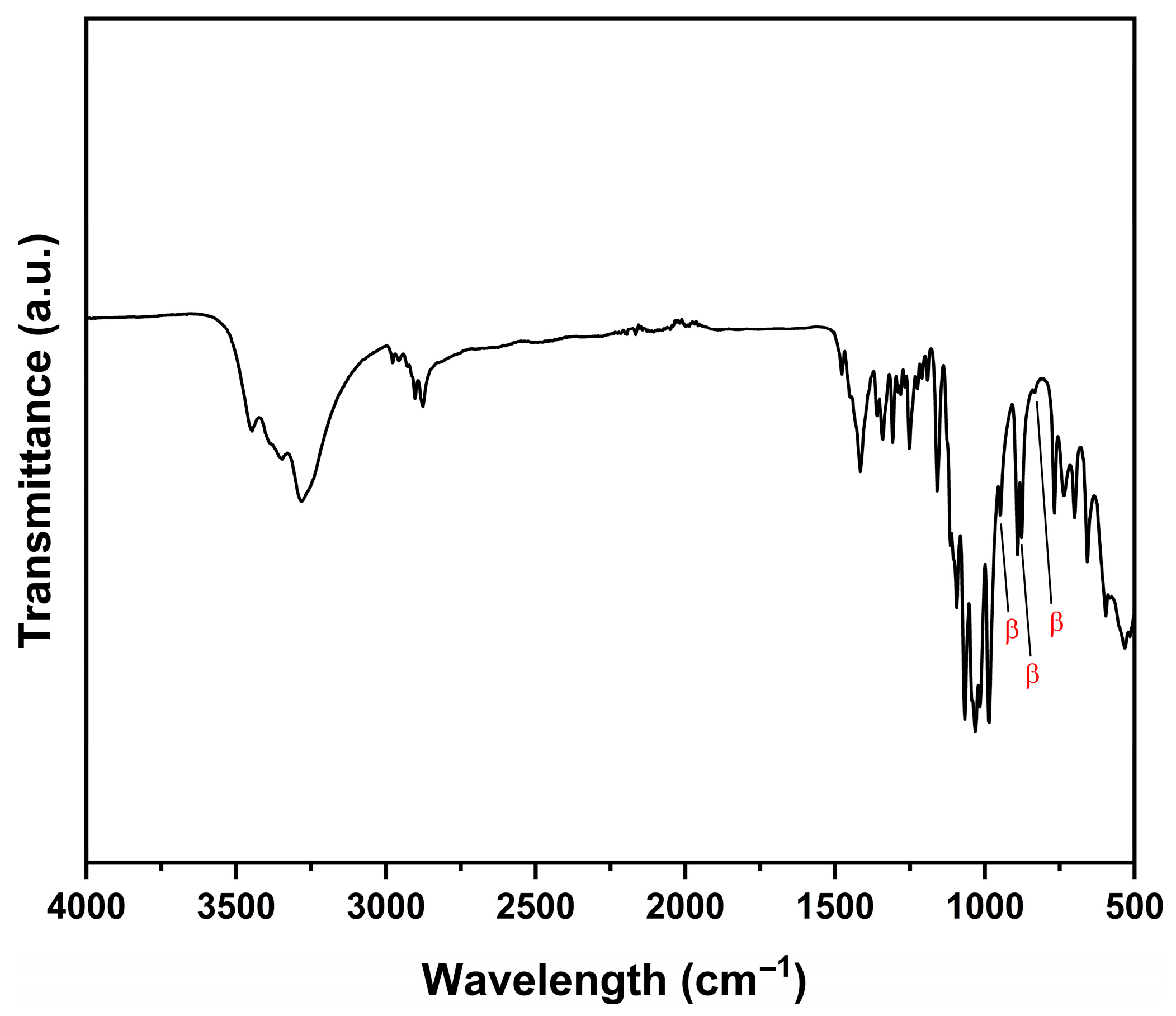

3.2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

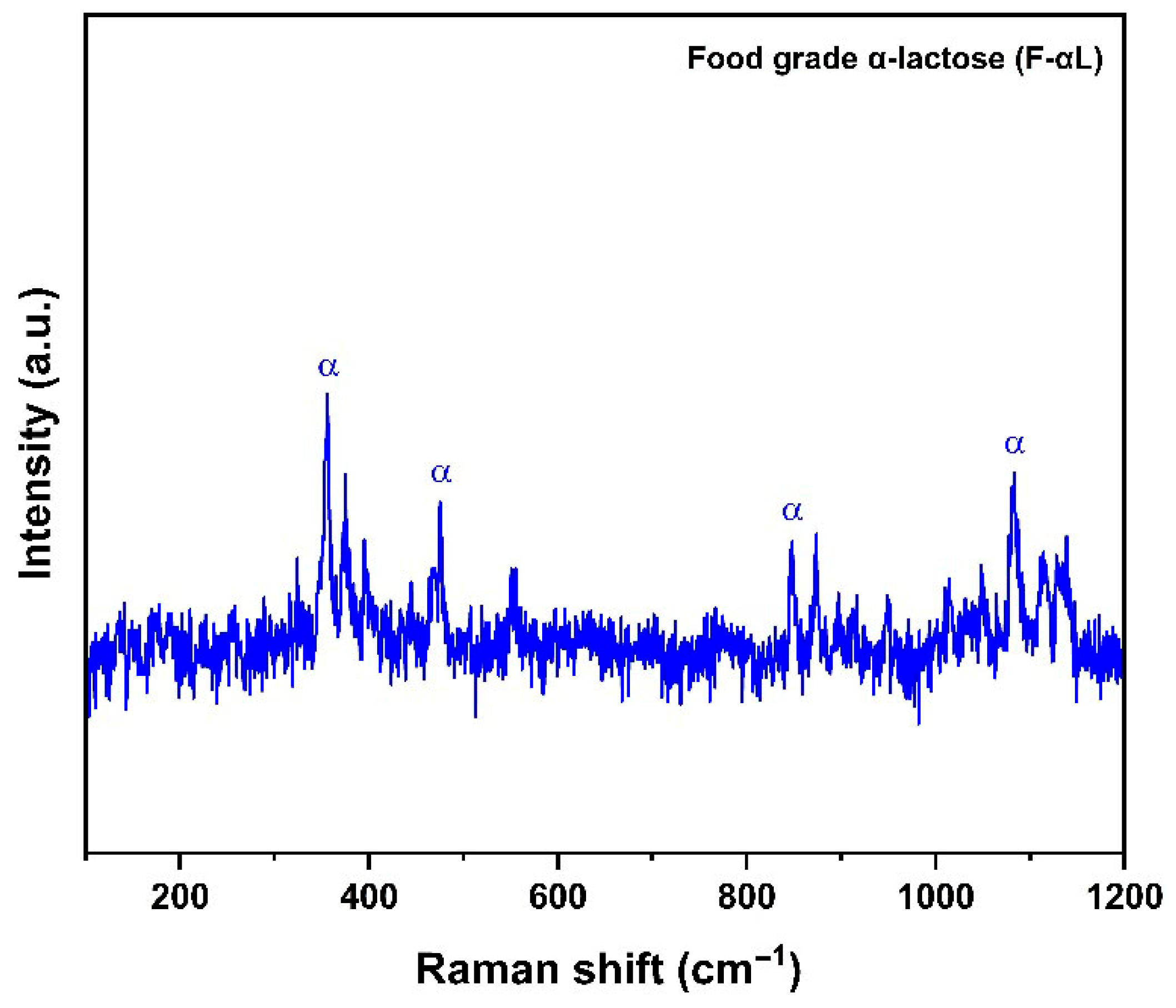

3.2.2. Raman Spectroscopy

3.3. Characterization of F-αL After the Mutarotation Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hudson, C.S. A review of discoveries on the mutarotation of the sugars. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1910, 32, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, M.; Barbano, D.M. Lactose: Use, measurement, and expression of results. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 8314–8325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.F.; McSweeney, P.L.H. (Eds.) Advanced Dairy Chemistry: Lactose, Water, Salts and Minor Constituents; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trespi, S.; Mazzotti, M. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Lactose mutarotation through Chromatography. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 5028–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listiohadi, Y.; Hourigan, J.A.; Sleigh, R.W.; Steele, R.J. Thermal analysis of amorphous lactose and α-lactose monohydrate. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2009, 89, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourigan, J.A.; Lifran, E.V.; Vu, L.T.; Listiohadi, Y.; Sleigh, R.W. Lactose: Chemistry, processing, and utilization. In Advances in Dairy Ingredients; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Ma, C.Y.; Styliari, I.D.; Gajjar, P.; Hammond, R.B.; Withers, P.J.; Roberts, K.J. Structure, morphology and surface properties of α-lactose monohydrate in relation to its powder properties. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 114, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clydesdale, G.; Roberts, K.J.; Telfer, G.B.; Grant, D.J. Modeling the crystal morphology of α-lactose monohydrate. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, J.H.; Dann, S.E.; Blatchford, C.G. Lactose: A definitive guide to polymorph determination. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 334, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walstra, P.; Walstra, P.; Wouters, J.T.; Geurts, T.J. Dairy Science and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.W. Free Water Necessary to Change Beta Anhydrous Lactose to Alpha Hydrous Lactose1. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1930, 22, 379–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerk, C.F. Consolidation and compaction of lactose. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1993, 19, 2359–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, T.; Martin, G.P.; Barlow, D.J.; Royall, P.G. Stability of α-lactose monohydrate: The discovery of dehydration triggered solid-state epimerization. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 604, 120715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altamimi, M.J.; Wolff, K.; Nokhodchi, A.; Martin, G.P.; Royall, P.G. Variability in the α and β anomer content of commercially available lactose. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 555, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.K.; Abd-Wahhab, K.G.; Abd El-Aziz, M. Lactose derivatives: Properties, preparation and their applications in food and pharmaceutical industries. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022, 65, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Mota, E.E.; Alvarez-Salas, C.; Leyva-Porras, C.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Cutting-edge advances on the stability and state diagram of pure β-lactose. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 289, 126477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, F.W.; Ross, K.D.; Valentine, K.M. Formation of β-lactose from the stable forms of anhydrous ã-lactose. J. Food Sci. 1980, 45, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pablos, A.L.; Leyva-Porras, C.C.; Silva-Cázares, M.B.; Longoria-Rodríguez, F.E.; Pérez-García, S.A.; Vértiz-Hernández, Á.A.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Preparation and Characterization of High Purity Anhydrous β-Lactose from α-Lactose Monohydrate at Mild Temperature. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2018, 2018, 5069063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Mota, E.E.; Nicolás–Vázquez, M.I.; López-Martínez, L.A.; Espinosa-Solis, V.; Cruz-Alcantar, P.; Toxqui-Teran, A.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Phenomenological study of the synthesis of pure anhydrous β-lactose in alcoholic solution. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 128054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici, S.; Marescotti, F.; Sanmartin, C.; Macaluso, M.; Taglieri, I.; Venturi, F.; Facioni, M.S. Lactose: Characteristics, food and drug-related applications, and its possible substitutions in meeting the needs of people with lactose intolerance. Foods 2022, 11, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxqui-Teran, A.; Lara-Mota, E.E.; Leyva-Porras, C.C.; Alvarez-Salas, C.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Moisture sorption phenomena of lactose anomers and evaluation of morphological stability. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 322, 129486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Bhandari, B.; Zhou, W. Impact of caramelization on the glass transition temperature of several caramelized sugars. Part I: Chemical analyses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5138–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Leos, M.Z.; Alvarez-Salas, C.; Esneider-Alcalá, M.A.; Toxqui-Terán, A.; Pérez-García, S.A.; Ruiz-Cabrera, M.A. Towards an improved calorimetric methodology for glass transition temperature determination in amorphous sugars. CyTA-J. Food 2012, 10, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijdam, J.; Ibach, A.; Eichhorn, K.; Kind, M. An X-ray diffraction analysis of crystallised whey and whey-permeate powders. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Lu, A.; Li, Y. Thermal and X-ray diffraction analysis of lactose polymorph. Procedia Eng. 2015, 102, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevis, J.; Bottom, R.; Duncan, J.; Farhat, I.; Forrest, M.; Furniss, D.; MacNaughton, B.; Nazhat, S.; Saunders, M.; Seddon, A. Principles and Applications of Thermal Analysis; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Hussain, A.; Bukhari, N.I.; Ermolina, I. Quantification of residual crystallinity in ball milled commercially sourced lactose monohydrate by thermo-analytical techniques and terahertz spectroscopy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 92, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnikova, E.; Bogdanova, E.; Paveleva, D.; Saranov, I. Sucrose, Lactose, Thermogravimetry, and Differential Thermal Analysis: The Estimation of the Moisture Bond Types in Lactose-Containing Ingredients for Confectionery Products with Reduced Glycemic Index. Int. J. Food Sci. 2023, 2023, 8835418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzobre, M.F.; Soto, G.; Aguilera, J.M.; Buera, M.P. Crystallization kinetics of lactose in sytems co-lyofilized with trehalose. Analysis by differential scanning calorimetry. Food Res. Int. 2001, 34, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra–Leos, M.Z.; Leyva-Porras, C.; Alvarez-Salas, C.; Longoria-Rodríguez, F.; López-Pablos, A.L.; González-García, R.; Pérez-Urizar, J.T. Obtaining orange juice–maltodextrin powders without structure collapse based on the glass transition temperature and degree of polymerization. CyTA-J. Food 2018, 16, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Porras, C.; Cruz-Alcantar, P.; Espinosa-Solís, V.; Martínez-Guerra, E.; Piñón-Balderrama, C.I.; Compean Martínez, I.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Application of differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and modulated differential scanning calorimetry (MDSC) in food and drug industries. Polymers 2019, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.K.; Kawai, K.; Suzuki, T. Glass transition and enthalpy relaxation of amorphous lactose glass. Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 341, 1884–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, J.J.; Hodnett, M.; Twomey, M.; Cerqueira, P.S.M.; O’flynn, J.; Roos, Y.H. Glass transition and the flowability and caking of powders containing amorphous lactose. Powder Technol. 2007, 178, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.Y.; Hartel, R.W. Crystallization in lactose refining—A review. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, R257–R272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.M.; Martin, G.P.; Marriott, C.; Pritchard, J. The influence of crystallization conditions on the morphology of lactose intended for use as a carrier for dry powder aerosols. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2000, 52, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G.; Haase, G.; Jelen, P. Lactose: Crystallization, hydrolysis and value-added derivatives. Int. Dairy J. 2008, 18, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, J.B.; Sun, S.Q.; Noda, I. Analysis of crystallized lactose in milk powder by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy combined with two-dimensional correlation infrared spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 974, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Xiang, P.; Zhao, L. Vibrational spectra analysis of amorphous lactose in structural transformation: Water/temperature plasticization, crystal formation, and molecular mobility. Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.M.; Prescott, S.W.; Larson, I. Measurement of lactose crystallinity using Raman spectroscopy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2005, 38, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nørgaard, L.; Hahn, M.T.; Knudsen, L.B.; Farhat, I.A.; Engelsen, S.B. Multivariate near-infrared and Raman spectroscopic quantifications of the crystallinity of lactose in whey permeate powder. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.I.U.; Langrish, T.A.G. An investigation into lactose crystallization under high temperature conditions during spray drying. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiercigroch, E.; Szafraniec, E.; Czamara, K.; Pacia, M.Z.; Majzner, K.; Kochan, K.; Kaczor, A.; Baranska, M.; Malek, K. Raman and infrared spectroscopy of carbohydrates: A review. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 185, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, P.L.; O’Mahony, J.A. Química Láctea Avanzada: Volumen 1B: Proteínas: Aspectos Aplicados; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kamp, H.V.; Bolhuis, G.K.; Kussendrager, K.D.; Lerk, C.F. Studies on tableting properties of lactose. IV. Dissolution and disintegration properties of different types of crystalline lactose. Int. J. Pharm. 1986, 28, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Wang, B.; Fu, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, W.; Tan, S. Tailoring α/β ratio of pollen-like anhydrous lactose as ingredient carriers for controlled dissolution rate. Crystals 2021, 11, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, Y.H. Solid and liquid states of lactose. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry: Volume 3: Lactose, Water, Salts and Minor Constituents; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J.F.; Chiu, W.S.; Gray, V.; Toale, H.; Tobyn, M.; Wu, Y. Investigation into the degree of variability in the solid-state properties of common pharmaceutical excipients—Anhydrous lactose. Aaps Pharmscitech 2010, 11, 1552–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lara-Mota, E.E.; Gutiérrez-Castañeda, E.J.; Cisneros-Almazán, R.; Escobar-Barrios, V.A.; Leyva-Porras, C.C.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Study of the Feasibility of Using Food-Grade Lactose as a Viable and Economical Alternative for Obtaining High-Purity β-Lactose. Processes 2026, 14, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020285

Lara-Mota EE, Gutiérrez-Castañeda EJ, Cisneros-Almazán R, Escobar-Barrios VA, Leyva-Porras CC, Saavedra-Leos MZ. Study of the Feasibility of Using Food-Grade Lactose as a Viable and Economical Alternative for Obtaining High-Purity β-Lactose. Processes. 2026; 14(2):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020285

Chicago/Turabian StyleLara-Mota, Edgar Enrique, Emmanuel José Gutiérrez-Castañeda, Rodolfo Cisneros-Almazán, Vladimir Alonso Escobar-Barrios, César C. Leyva-Porras, and María Zenaida Saavedra-Leos. 2026. "Study of the Feasibility of Using Food-Grade Lactose as a Viable and Economical Alternative for Obtaining High-Purity β-Lactose" Processes 14, no. 2: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020285

APA StyleLara-Mota, E. E., Gutiérrez-Castañeda, E. J., Cisneros-Almazán, R., Escobar-Barrios, V. A., Leyva-Porras, C. C., & Saavedra-Leos, M. Z. (2026). Study of the Feasibility of Using Food-Grade Lactose as a Viable and Economical Alternative for Obtaining High-Purity β-Lactose. Processes, 14(2), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020285