Abstract

Duplications of chromosome 16p11.2, even though rare in the general population, are one of the most frequent known genetic causes of autism spectrum disorder and of other neurodevelopmental disorders. However, data about the neuro-behavioral phenotype of these patients are few. We described a sample of children with duplication of chromosome 16p11.2 focusing on the neuro-behavioral phenotype. The five patients reported presented with very heterogeneous conditions as for characteristics and severity, ranging from a learning disorder in a child with normal intelligence quotient to an autism spectrum disorder associated with an intellectual disability. Our case report underlines the wide heterogeneity of the neuropsychiatric phenotypes associated with a duplication of chromosome 16p11.2. Similarly to other copy number variations that are considered pathogenic, the wide variability of phenotype of chromosome 16p11.2 duplication is probably related to additional risk factors, both genetic and not genetic, often difficult to identify and most likely different from case to case.

1. Introduction

Duplications of chromosome 16p11.2 (dup16p11.2), even though rare in the general population (about 0.07% according to Tucker et al., 2013) [1], are one of the most frequent known genetic causes of autism spectrum disorder (about 0.5% according to Levy et al., 2011) [2] and of other neurodevelopmental disorders including developmental delay, intellectual disability, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), developmental coordination disorder, and language disorders [3,4]. Steinman et al. described the neurologic phenotype of dup16p11.2: dysarthria; hypotonia; motor dysrhythmia; microcephaly or macrocephaly; weakness; focal or generalized epilepsy; hyperreflexia or hyporeflexia; eye convergence abnormalities; tremor; tics; electroencephalogram (EEG) focal sharp activity; white matter/corpus callosum abnormalities and ventricular enlargement shown by brain imaging [4]. Regarding psychiatric disorders, in their systematic review, Giaroli et al. found in dup16p11.2 individuals a 14-fold increased risk of psychosis (including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder) [5]. Anxiety disorders (including obsessive compulsive disorder) and mood disorders have also been reported [3]. However, data about the neuro-behavioral phenotype of dup16p11.2 carriers are few [6,7]. We dealt with this topic in a sample of pediatric patients.

2. Case Presentation

During the period from 2013 to 2020, in the 347 children referred to our Center for a neurodevelopmental disorder (according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition: DSM-5) [8] and who have undergone array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), we found five (1.4% of the total) dup16p11.2 carriers, all of Caucasian ethnicity. They were four males and one female; two of them were brothers; age at last observation ranged from 7 years 3 months to 15 years 10 months. The size of dup16p11.2 ranged from 59 Kb to 590 Kb. Based on the analysis of segregation in the parents, in four of our patients the duplication was derived from the father, while in one case it was derived from the mother. Only the father of the first two cases had a psychiatric clinical picture attributable to the duplication, while the other parents carrying the duplication were healthy; although intelligence quotient (IQ) assessment was not available, their educational and vocational history were normal.

According to our evaluation, the five patients reported presented with very heterogeneous conditions as for characteristics and severity, from a learning disorder in a child with normal intelligence quotient (IQ) (case 2) to an autism spectrum disorder associated with an intellectual disability (case 1 and 5). Our five patients underwent a neuro-behavioral assessment using standardized tools including Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) (cases 2 and 4) or, when language impairment was severe, Leiter International Performance Scale, Revised (Leiter-R) (cases 1, 3, and 5) for evaluating the IQ; “Batteria di Valutazione Neuropsicologica”, an Italian tool used for evaluating cognitive functions such as language, attention, memory, and learning in childhood and adolescence; Child Behavior CheckList (CBCL) (DSM-oriented scales), a questionnaire administered to the parents for evaluating behavior problems; and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Second Edition (ADOS-2) [9], the gold standard tool for the evaluation of social-communicative competences and range of interests and behaviors when an autism spectrum disorder is suspected. Module 1 of ADOS-2 was administered in cases 1, 3, and 5; module 2 in case 4; and module 3 in case 2. We considered also the calibrated severity score of ADOS-2, a measure of autism symptom severity ranging from 1 (corresponding to a typical development) to 10 (maximum severity of autism). Informed consent, covering also the anonymous publication of case reports, was obtained from the patients’ parents.

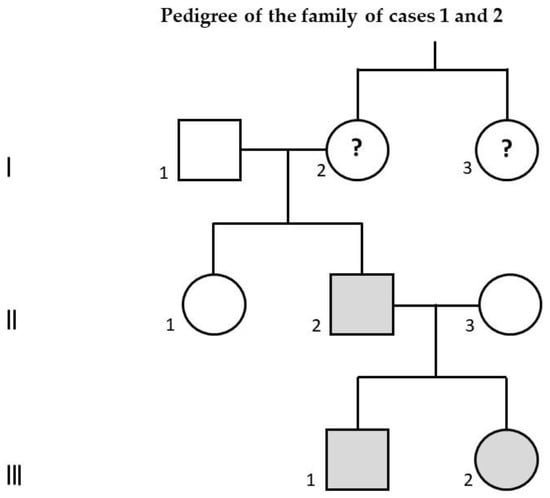

Table 1 and Table 2 describe the main genetic, clinical, instrumental, and in particular the neuro-behavioral features of each of the five individuals with dup16p11.2 we reported. Figure 1 represents the pedigree of the family of cases 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Genetic and clinical features of five cases with dup16p11.2.

Table 2.

Neuro-behavioral, clinical, and instrumental features of five cases with dup16p11.2.

Figure 1.

Family pedigree of case 1 (III-1), affected by autism spectrum disorder associated with intellectual disability, and of case 2 (III-2), affected by learning disability. Their father (II-2), presenting with the same 16p11.2 duplication, is affected by schizophrenia. His aunt (I-3) is also affected by schizophrenia: in her, the 16p11.2 duplication has not been documented and therefore it is only a hypothesis; if she were really a carrier of this duplication, evidently the paternal grandmother of cases 1 and 2 (I-2) would be a healthy carrier of 16p11.2 duplication. Gray color: confirmed carriers of 16p11.2 duplication; question mark: hypothetical carriers of 16p11.2 duplication.

Some comments on the description of the five cases follow. For cases 1, 3, and 4, the learning difficulties we reported reflect lower overall cognitive functioning and are not to be considered specific. Concerning the epileptic seizures of cases 1 and 3, unfortunately, based on the available clinical and electrophysiological data of our patients, a syndromic classification is not possible, also because the semiology of the seizures is apparently not in line with the features of the EEG. The paroxysmal events reported for case 3 after the age of 7 years 9 months are probably not epileptic; a possible alternative diagnostic hypothesis is that of a periodic paralysis.

3. Discussion

Our case report confirms the wide heterogeneity of the clinical neuropsychiatric phenotypes associated with dup16p11.2, ranging from an at least apparently normal condition (see in particular the three healthy parents who were carriers of the same duplication of the affected sons) to a severe impairment of neurodevelopment such as an autism spectrum disorder associated with an intellectual disability, with a series of intermediate conditions including an intellectual disability combined with developmental disorders outside the autism spectrum. These findings led us to formulate some hypotheses in order to explain the clinical heterogeneity of dup16p11.2 carriers. First of all, one involved variable could be the size of the duplication. However, based on the analysis of our sample, this variable does not seem to be determining since case 5, carrier of the smallest duplication (only 59 Kb, partially overlapping with the duplications found in case 1, 2, and 4), is one of the two individuals with the greatest impairment, being affected by autism spectrum disorder plus intellectual disability. Another variable underlying this clinical heterogeneity could be the concomitant presence of another copy number variation (CNV) detected by the aCGH, according to the so-called two-hit hypothesis. The only associated CNV involving genes that we found is a deletion of 7q31.1 in case 5, which includes intron 5 of inner mitochondrial membrane peptidase 2-like (IMMP2L) gene, whose mutations/deletions have been associated with several neuropsychiatric disorders including Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, ADHD, developmental delay, and also autism spectrum disorder [10]. It cannot be excluded that this CNV might have contributed to the clinical picture of case 5, also considering the motor tics he presented. Moreover, it should be stressed that additional genetic factors modifying the dup16p11.2 clinical picture could be represented by mutations of single genes that can be highlighted by the whole-exome sequencing, not by the aCGH, and that have not been considered in this paper. It should also be emphasized that even the deletions that do not involve genes (see case 4 and case 5) could play a role in the expression of the phenotype, due to their possible function of regulating genes that are located elsewhere [11]. Finally, a further variable underlying the clinical heterogeneity of dup16p11.2, as for the CNVs in general, could be represented by the concomitant presence of environmental factors, which of course are somewhat difficult to study due to the very high number of factors that could theoretically be involved: pre- and perinatal hypoxic-ischemic suffering, early exposure to environmental pollutants and to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, just to give some possible examples [12].

As a final consideration, we underline the presence in all our patients of heterogeneous sleep disorders and the lack in our cases of specific facial and body dysmorphisms. The first finding could further suggest a link between neurodevelopmental disorders and 16p11.2 duplication, since sleep disorders are an early clinical feature frequently reported in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. The lack of specific dysmorphisms, which is a feature common to many CNVs, once again suggests the importance of carrying out genetic tests such as the array-CGH even in cases in which the phenotype is characterized solely by a neurodevelopmental disorder, in the absence of somatic peculiarities.

We are well aware of the limitations of this study due to the low number of our case series, however we believe that the considerations originating from the analysis of our patients could stimulate the scientific debate about the neuro-behavioral phenotype in 16p11.2 duplication, also because in literature data specifically about this topic are few.

In conclusion, similarly to other CNVs that are considered pathogenic, the wide variability of dup16p11.2 phenotype, ranging from a normal condition to severe impairment of the neurodevelopment, according to Green Snyder et al. [3], is probably related to additional risk factors, both genetic (including associated CNVs or mutations of single genes) and not genetic (i.e., environmental: see above), often difficult to identify and most likely different from case to case.

Author Contributions

A.P. collected data, conducted data analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. P.V. designed the case report, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cecilia Baroncini for linguistic support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tucker, T.; Giroux, S.; Clément, V.; Langlois, S.; Friedman, J.M.; Rousseau, F. Prevalence of selected genomic deletions and duplications in a French-Canadian population-based sample of newborns. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2013, 1, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, D.; Ronemus, M.; Yamrom, B.; Lee, Y.H.; Leotta, A.; Kendall, J.; Marks, S.; Lakshmi, B.; Pai, D.; Ye, K.; et al. Rare de novo and transmitted copy-number variation in autistic spectrum disorders. Neuron 2011, 70, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green Snyder, L.; D’Angelo, D.; Chen, Q.; Bernier, R.; Goin-Kochel, R.P.; Wallace, A.S.; Gerdts, J.; Kanne, S.; Berry, L.; Blaskey, L.; et al. Simons VIP consortium. Autism spectrum disorder, developmental and psychiatric features in 16p11.2 duplication. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 2734–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinman, K.J.; Spence, S.J.; Ramocki, M.B.; Proud, M.B.; Kessler, S.K.; Marco, E.J.; Green Snyder, L.; D’Angelo, D.; Chen, Q.; Chung, W.K.; et al. Simons VIP Consortium. 16p11.2 deletion and duplication: Characterizing neurologic phenotypes in a large clinically ascertained cohort. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2016, 170, 2943–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaroli, G.; Bass, N.; Strydom, A.; Rantell, K.; McQuillin, A. Does rare matter? Copy number variants at 16p11.2 and the risk of psychosis: A systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 159, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, D.; Lebon, S.; Chen, Q.; Martin-Brevet, S.; Snyder, L.G.; Hippolyte, L.; Hanson, E.; Maillard, A.M.; Faucett, W.A.; Macé, A.; et al. Cardiff University Experiences of Children with Copy Number Variants (ECHO) Study; 16p11.2 European Consortium; Simons Variation in Individuals Project (VIP) Consortium. Defining the effect of the 16p11.2 duplication on cognition, behavior, and medical comorbidities. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niarchou, M.; Chawner, S.J.R.A.; Doherty, J.L.; Maillard, A.M.; Jacquemont, S.; Chung, W.K.; Green-Snyder, L.; Bernier, R.A.; Goin-Kochel, R.P.; Hanson, E.; et al. Psychiatric disorders in children with 16p11.2 deletion and duplication. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C.; Rutter, M.; DiLavore, P.C.; Risi, S.; Gotham, K.; Bishop, S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd ed.; (ADOS-2) Manual (Part I): Modules 1–4; Western Psychological Services: Torrance, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baldan, F.; Gnan, C.; Franzoni, A.; Ferino, L.; Allegri, L.; Passon, N.; Damante, G. Genomic deletion involving the IMMP2L gene in two cases of autism spectrum disorder. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2018, 154, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielmann, M.; Mundlos, S. Looking beyond the genes: The role of non-coding variants in human disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, R157–R165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posar, A.; Visconti, P. Autism in 2016: The need for answers. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2017, 93, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).