Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a complex clinical challenge, caused by a novel coronavirus, partially similar to previously known coronaviruses but with a different pattern of contagiousness, complications, and mortality. Since its global spread, several therapeutic agents have been developed to address the heterogeneous disease treatment, in terms of severity, hospital or outpatient management, and pre-existing clinical conditions. To better understand the rationale of new or old repurposed medications, the structure and host–virus interaction molecular bases are presented. The recommended agents by EDSA guidelines comprise of corticosteroids, JAK-targeting monoclonal antibodies, IL-6 inhibitors, and antivirals, some of them showing narrow indications due to the lack of large population trials and statistical power. The aim of this review is to present FDA-approved or authorized for emergency use antivirals, namely remdesivir, molnupinavir, and the combination nirmatrelvir-ritonavir and their impact on the cardiovascular system. We reviewed the literature for metanalyses, randomized clinical trials, and case reports and found positive associations between remdesivir and ritonavir administration at therapeutic doses and changes in cardiac conduction, relatable to their previously known pro-arrhythmogenic effects and important ritonavir interactions with cardioactive medications including antiplatelets, anti-arrhythmic agents, and lipid-lowering drugs, possibly interfering with pre-existing therapeutic regimens. Nonetheless, safety profiles of antivirals are largely questioned and addressed by health agencies, in consideration of COVID-19 cardiac and pro-thrombotic complications generally experienced by predisposed subjects. Our advice is to continuously adhere to the strict indications of FDA documents, monitor the possible side effects of antivirals, and increase physicians’ awareness on the co-administration of antivirals and cardiovascular-relevant medications. This review dissects the global and local tendency to structure patient-based treatment plans, for a glance towards practical application of precision medicine.

1. Introduction: COVID-19 Pandemic, a Novel Biological Entity for a Modern Clinical Challenge

1.1. SARS-CoV-2 Global Effects and Possible Management Strategies

The COVID-19 global pandemic has involved 288,195,906 confirmed cases, including 5,454,751 deaths, as reported by World Health Organization (WHO) as of 31 December 2021 [1].

The causative infective agent is a novel coronavirus consisting of a single strand of positive-sense RNA, initially termed “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2) by the Coronaviridae Study Group (CSG) of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses in February 2020 [2,3,4].

Previously, two other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, were identified as belonging to the same genus and responsible for fast-spreading epidemics. Since then, scientists have investigated and pointed out the differences in mortality and contagiousness rates that linked these three human coronaviruses. While SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV reported death rates of 10–15% and 37% respectively, SARS-CoV-2 showed a lower mortality rate than the former two [5]. Other major differences include longer incubation time after initial infection (1–2 weeks) and a more conspicuous reservoir of infected people spreading SARS-CoV-2 in an asymptomatic state.

The World Health Organization has indicated Europe as the epicenter of the pandemic recovery from SARS-CoV-2 for the winter of 2022 [1]. The arduous task of curbing the thrust of the pandemic has directed scientists towards an acceleration in research programs, obtaining extraordinary results in a short time.

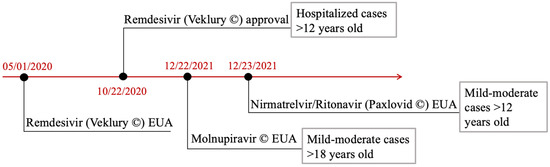

The researchers’ work led to the development, among others, of BNT162b2 mRNA and mRNA-1273 vaccines developed by Pfizer/BioNtech and Moderna companies and of Ad26.COV2.S, a recombinant, replication-incompetent human adenoviral vector by Johnson and Johnson which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [6,7,8]. Concerning therapeutic agents, small molecule antiviral drugs including remdesivir and molnupinavir have been clinically tested. Remdesivir, after its approval on 22 October 2020, has already been used according to guidelines [9].

Moreover, evidence has shown that SARS-CoV-2 continues to mutate at a rate of approximately 106 per site per cycle resulting in several variants with uncontrolled dissemination among humans [10,11]. There were suggestions that the vaccines, rather than therapeutic agents, proved less effective on virus mutations [12]. Furthermore, with the possible emergence of future coronavirus variants, the development of new antiviral agents remains pivotal in terms of preparing for new outbreaks.

Simultaneously, severe respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms, among certain vulnerable populations, have raised concerns with an emphasis on clinical attempts to diminish the risk of spread, especially to these cohorts.

Recently, investigators have focused their attention on cardiac and thrombotic complications, to which clot-promoting autoantibodies are likely to arise. Zuo et al. [13] drew on previous evidence by highlighting points of convergence between blood clotting anomalies in patients with COVID-19 and those with autoimmune clotting clinical condition such as antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

It is vital to therefore consider antivirals’ safety, mostly to implement existing guidelines and counterbalance unrestrained viral replication effects, responsible for the inflammatory complications [14]. However, the role of antivirals should not be to replace vaccines but rather to act as additional complements for the treatment of infection caused by the wild-type parent virus (WT) than for that caused by variants.

Evidence suggests that some of these viral replication inhibitors met the validity criteria for consideration by major American and European drug agencies. We deeply believe structural and functional details of SARS-CoV-2 are fundamental for understanding the ongoing efforts to implement antiviral therapies.

1.2. Structure, Genomics, and Viral Particle–Host Interaction

SARS-CoV-2 has a spherical shape and multiple components are essential for its replication and transcription: several club-like projections on the surface of the envelope representing the spike glycoprotein (S), which permits the adhesion to the host cell and induces antibody neutralization; the envelope protein membrane (E); the structural membrane protein (M), which is across the lipid bilayer; the hemagglutinin-esterase glycoprotein (HE), which interacts with the sialic acid on the host cell inactivating it and helping the virus inject its genetic material inside cellular cytoplasm; the nucleoprotein (N); and the positive-sense single-stranded RNA [15,16,17].

The genome size of COVID-19 is about 26.4–31.7 Kb (kilobases). Inside the viral genome, several open reading frames (ORF) can be observed along with untranslated regions (UTR). ORF1a/b (29.8 Kb size) encodes the replicase polyprotein named pp1a protein and 16 accessory non-structural proteins (nsps) while ORF1b codes for pp1b and 10 nsps [18,19,20,21]. ORFs 10 and 11 encode structural proteins such as spike (S), envelope (E), membrane protein (M), and nucleoprotein (N). ORF3, ORF7a, ORF7b, and ORF8 produce other essential accessory proteins [22].

SARS-CoV-2 has some genomic differences compared to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Some of the variabilities make SARS-CoV-2 more virulent than the other two viruses. A single mutation at N501T in the spike protein enhances the binding efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) [23].

To date, we have identified six different clades of SARS-CoV-2: (1) L clade (originated in Wuhan, China and the similar ORF8-L84S clade), (2) S clade (mutation of ORF8, L84S), (3) V clade (variant of ORF3a coding protein NS3, G251V), (4) G clade (mutation in spike protein, D614G), (5) GH clade (mutations in spike protein, D614G and ORF3a, Q57H), and (6) GR clade (mutation in nucleocapsid gene, RG203KR) [24,25]. G and GR clades are predominant in Europe, while GH is more common in North America.

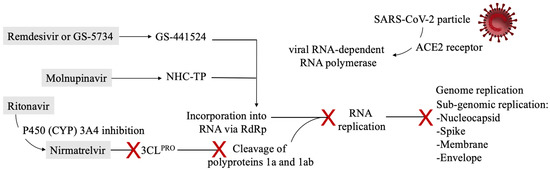

Once in the host system, SARS-CoV-2 enters the cell. The spike protein binds the virus to ACE2 receptor on the surface of the cell [26], it fuses to the cell membrane and enters into the cytoplasm by endosomic transport. Once inside the cell, the virus releases its genomic RNA and multiplies using the molecular structures of the cell. Transmembrane Serine Protease 2 (TMPRSS2) and lysosomal cathepsin activate SARS-CoV-2 entry [27].

1.3. Viral Proteases: Crucial Antivirals Therapeutic Targets

The main protease (Mpro) and papain-like protease (PLpro) are the most pursued viral proteins as SARS-CoV-2 antiviral drug targets [21]. They have been shown to be the most promising in inhibiting viral replication. The action of Mpro and PLpro is directed towards the proteolytic digestion of the viral polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab which leads to the formation of single viral proteins functional for the formation of the replication complex [28]. Specifically, three sites with the recognition sequence “LXGG ↓ XX” are cleaved by PLpro.

Shin et al. [29] reported an essential additional PLpro role concerning the dysregulatory action of the host’s immune response through an effective impairment of the antiviral effect of the host’s type I interferon. This intervention is mediated through its deubiquitinating and de-ISG15-ylating (interferon-induced gene 15) activities, respectively. Fu et al. [30] proved that SARS-CoV-2 PLpro intervenes to cleave ISG15 and induce modifications of polyubiquitin from cellular proteins. Therefore, inhibition of PLpro can lead to the accumulation of ISG15 conjugates and conjugates of polyubiquitin. This study reinforced the evidence from several reports suggesting substantial differences of PLpro in acting on substrates that concern SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV-2 replication. In fact, contrary to SARS-CoV PLpro, which prefers ubiquitinated substrates, SARS-CoV-2 PLpro prefers ISGlyated proteins as substrates [30]. The peculiar characteristic of PLpro is its belonging to a membrane-anchored multidomain protein named nonstructural protein 3 (nsp-3), which constitutes a fundamental component of the replicase−transcriptase complex.

As SARS-CoV-2 PLpro has been shown to have pleitropic roles, this makes it a promising target for antiviral drugs.

5. Conclusions

The pandemic has given rise to a good response from the scientific community with the availability of multiple therapeutic agents and vaccines. Vaccines continue to provide sufficient protection from spread and contagion although their response varies with disease variants [58,129,130]. There is an ongoing push towards biological agents and retrovirals to reduce the severity and duration of symptoms with mixed results. As with many advances in therapeutics, ongoing monitoring, reporting, and updates are required to ensure safety and efficacy for the generalized use of these medications especially in patients with multiple comorbidities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.N. and A.I.; methodology, F.N.; software, A.I.; validation, F.N., A.I. and S.S.A.S.; formal analysis, F.N.; investigation, F.N.; data curation, F.N. and A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, F.N.; writing—review and editing, F.N., A.I. and S.S.A.S.; visualization, F.N. and A.I.; supervision, F.N., A.I. and S.S.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACE1 | angiotensin I-converting enzyme, |

| ACE2 | angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, |

| Ang-II | angiotensin II, |

| Ang-I | angiotensin I, |

| Ang 1–7 | angiotensin 1–7, |

| APS | antiphospholipid syndrome, |

| ARBs | angiotensin II receptor blockers, |

| AT1R | angiotensin type 1 receptor, |

| AUC0–6h | area under the curve, |

| CAD | coronary artery disease, |

| CCBs | calcium channel blockers, |

| Cmax | maximum concentration, |

| CSG | Coronaviridae Study Group, |

| CYP | cytochrome P450, |

| DDIs | drug–drug interactions, |

| E | envelope, |

| ECMO | extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency, |

| EUA | Emergency Use Administration, |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration, |

| JAK-STAT | Janus kinase and signal transducer and activator of transcription, |

| Kb | kilobases |

| ICU | intensive care unit, |

| IDSA | Infectious Diseases Society of America, |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6, |

| INR | international normalized ratio, |

| LQTs | long Q-T syndromes, |

| M | membrane, |

| MERS-CoV | Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, |

| Mpro | main protease, |

| N | nucleoprotein, |

| NHC-TP | β-D-N4-hydroxycytidine 5′-triphosphate, |

| nsp-3 | nonstructural protein 3, |

| ORF | open reading frames, |

| PAD | peripheral artery disease, |

| PLpro | papain-like protease, |

| RAAS | renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, |

| RCTs | randomized clinical trials, |

| RdRp | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid, |

| RTP | remdesivir triphosphate, |

| SARS-CoV | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, |

| TMPRSS2 | transmembrane serine protease 2, |

| UTR | untranslated regions, |

| VF | ventricular fibrillation, |

| VT | ventricular tachycardia, |

| WHO | World Health Organization, |

| WT | wild-type, |

| 3CLPRO | 3C-like protease. |

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.-W.; Tian, J.-H.; Pei, Y.-Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abdelghany, T.; Ganash, M.; Bakri, M.M.; Qanash, H.; Al-Rajhi, A.M.; Elhussieny, N.I. SARS-CoV-2, the other face to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV: Future predictions. Biomed. J. 2020, 44, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoff, J.; Gray, G.; Vandebosch, A.; Cárdenas, V.; Shukarev, G.; Grinsztejn, B.; Goepfert, P.A.; Truyers, C.; Fennema, H.; Spiessens, B.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2187–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, R.T.; Roth, J.S.; Brimacombe, K.R.; Simeonov, A.; Shen, M.; Patnaik, S.; Hall, M.D. Remdesivir: A Review of Its Discovery and Development Leading to Emergency Use Authorization for Treatment of COVID-19. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Flamholz, A.; Phillips, R.; Milo, R. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers. eLife 2020, 9, e57309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauring, A.S.; Hodcroft, E.B. Genetic Variants of SARS-CoV-2—What Do They Mean? JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2021, 325, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.Y.; Jeong, H.W.; Shin, E.-C. SARS-CoV-2 mutations, vaccines, and immunity: Implication of variants of concern. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Y.; Estes, S.K.; Ali, R.A.; Gandhi, A.A.; Yalavarthi, S.; Shi, H.; Sule, G.; Gockman, K.; Madison, J.A.; Zuo, M.; et al. Prothrombotic autoantibodies in serum from patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eabd3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.A.M.P.J.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; van Paassen, J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020, 191, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavizadeh, L.; Ghasemi, S. Genotype and phenotype of COVID-19: Their roles in pathogenesis. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 54, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtipal, N.; Bharadwaj, S.; Kang, S.G. From SARS to SARS-CoV-2, insights on structure, pathogenicity and immunity aspects of pandemic human coronaviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 85, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guo, D. Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, K.; Ye, G.; Wu, W.; Sun, Z.; Liu, F.; Wu, K.; Zhong, B.; et al. RNA based mNGS approach identifies a novel human coronavirus from two individual pneumonia cases in 2019 Wuhan outbreak. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Peng, Y.; Huang, B.; Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Niu, P.; Meng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Genome Composition and Divergence of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Originating in China. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, R.; Kumari, S.; Pandey, B.; Mistry, H.; Bihani, S.C.; Das, A.; Prashar, V.; Gupta, G.D.; Panicker, L.; Kumar, M. Structural insights into SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 433, 166725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-J.; Yang, D.-M.; Wang, M.-L.; Liang, K.-H.; Tsai, P.-H.; Chiou, S.-H.; Lin, T.-H.; Wang, C.-T. Genomic analysis and comparative multiple sequences of SARS-CoV2. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2020, 83, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Shang, J.; Graham, R.; Baric, R.S.; Li, F. Receptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus fromWuhan: An Analysis Based on Decade-Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00127-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; O0Toole, A.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Ruis, C.; du Plessis, L.; Pybus, O.G. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, S.; Netland, J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: Update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Chiaravalli, J.; Gellenoncourt, S.; Brownridge, P.; Bryne, D.P.; Daly, L.A.; Grauslys, A.; Walter, M.; Agou, F.; Chakrabarti, L.A.; et al. Characterising proteolysis during SARS-CoV-2 infection identifies viral cleavage sites and cellular targets with therapeutic potential. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Mukherjee, R.; Grewe, D.; Bojkova, D.; Baek, K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Schulz, L.; Widera, M.; Mehdipour, A.R.; Tascher, G.; et al. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature 2020, 575, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Huang, B.; Tang, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Ye, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, W.; Cao, D.; et al. The complex structure of GRL0617 and SARS-CoV-2 PLpro reveals a hot spot for antiviral drug discovery. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, C.; Ginex, T.; Maestro, I.; Nozal, V.; Barrado-Gil, L.; Cuesta-Geijo, M.; Urquiza, J.; Ramírez, D.; Alonso, C.; Campillo, N.E.; et al. COVID-19: Drug Targets and Potential Treatments. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 12359–12386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimraj, A.; Morgan, R.L.; Shumaker, A.H.; Lavergne, V.; Baden, L.; Cheng, V.C.; Edwards, K.M.; Gandhi, R.; Gallagher, J.; Muller, W.J.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients with COVID-19. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2022. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, ciaa478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Shi, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, W.; Xiao, G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, M.J.; Bergeron, E.; Benjannet, S.; Erickson, B.R.; Rollin, P.E.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Seidah, N.G.; Nichol, S.T. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol. J. 2005, 2, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Cao, R.; Xu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, W.; Wang, M. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The RECOVERY Collaborative Group Effect of Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2030–2040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium; Pan, H.; Peto, R.; Henao-Restrepo, A.-M.; Preziosi, M.-P.; Sathiyamoorthy, V.; Abdool Karim, Q.; Alejandria, M.M.; Hernández García, C.; Kieny, M.-P.; et al. 1 Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for COVID-19—Interim WHO Solidarity Trial Results. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chi, G.; Montazerin, S.M.; Lee, J.J.; Kazmi, S.H.A.; Shojaei, F.; Fitzgerald, C.; Gibson, C.M. Effect of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: Network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 6737–6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanni, S.E.; Bacha, H.A.; Naime, A.; Bernardo, W.M. Use of hydroxychloroquine to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and treat mild COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2021, 47, e20210236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Jhou, H.; Ou-Yang, L.; Lee, C. Does hydroxychloroquine reduce mortality in patients with COVID-19? A meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivese, T.; Musa, O.A.; Hindy, G.; Al-Wattary, N.; Badran, S.; Soliman, N.; Aboughalia, A.T.; Matizanadzo, J.T.; Emara, M.M.; Thalib, L.; et al. Efficacy of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19 infection: A meta-review of systematic reviews and an updated meta-analysis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 43, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, B.; Khanijahani, A.; Amani, B. Hydroxychloroquine plus standard of care compared with standard of care alone in COVID-19: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.C. Interleukin-6 Receptor Antagonists in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19—Preliminary report. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, I.O.; Bräu, N.; Waters, M.; Go, R.C.; Hunter, B.D.; Bhagani, S.; Skiest, D.; Aziz, M.S.; Cooper, N.; Douglas, I.S.; et al. Tocilizumab in Hospitalized Patients with Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermine, O.; Mariette, X.; Tharaux, P.L.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Porcher, R.; Ravaud, P.; CORIMUNO-19 Collaborative Group. Effect of Tocilizumab vs Usual Care in Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19 and Moderate or Severe Pneumonia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 181, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, C.; Han, J.; Yau, L.; Reiss, W.G.; Kramer, B.; Neidhart, J.D.; Criner, G.J.; Kaplan-Lewis, E.; Baden, R.; Pandit, L.; et al. Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvarani, C.; Dolci, G.; Massari, M.; Merlo, D.F.; Cavuto, S.; Savoldi, L.; Bruzzi, P.; Boni, F.; Braglia, L.; Turrà, C.; et al. Effect of Tocilizumab vs Standard Care on Clinical Worsening in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 181, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.H.; Frigault, M.J.; Serling-Boyd, N.J.; Fernandes, A.D.; Harvey, L.; Foulkes, A.S.; Horick, N.K.; Healy, B.C.; Shah, R.; Bensaci, A.M.; et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, V.C.; Prats, J.A.G.G.; Farias, D.L.C.; Rosa, R.G.; Dourado, L.K.; Zampieri, F.G.; Machado, F.R.; Lopes, R.D.; Berwanger, O.; Azevedo, L.C.P.; et al. Effect of tocilizumab on clinical outcomes at 15 days in patients with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2021, 372, n84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): Preliminary results of a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Turrini, E.; Raschi, E.; Sestili, P.; Fimognari, C. Janus Kinase Inhibitors and Coronavirus Disease (COVID)-19: Rationale, Clinical Evidence and Safety Issues. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescu, D.F.; Kalil, A.C. Janus Kinase inhibitors for the treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2021, 27, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, S.; Ogata, F.; Tsunoda, R. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with Janus kinase inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis: Case presentation and literature review. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 4457–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connors, J.M.; Levy, J.H. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood 2020, 135, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanff, T.C.; Mohareb, A.M.; Giri, J.; Cohen, J.; Chirinos, J.A. Thrombosis in COVID-19. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.A.; Frishman, W.H. Thrombotic Complications of COVID-19 Infection. Cardiol. Rev. 2020, 29, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Ceccarelli, G.; Cangemi, R.; Cipollone, F.; D’Ardes, D.; Oliva, A.; Pirro, M.; Rocco, M.; Alessandri, F.; D’Ettorre, G.; et al. Arterial and venous thrombosis in coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19): Relationship with mortality. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2021, 16, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, F.; Iervolino, A.; Singh, S.A. COVID-19 Pathogenesis: From Molecular Pathway to Vaccine Administration. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, G.P.; Mulani, J. Corticosteroids for COVID-19: The search for an optimum duration of therapy. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 9, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, D.C.; Derde, L.; Al-Beidh, F.; Annane, D.; Arabi, Y.; Beane, A.; van Bentum-Puijk, W.; Berry, L.; Bhimani, Z.; Bonten, M.; et al. Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID-19: The REMAP-CAP COVID-19 corticosteroid domain randomised clinical trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 131729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, L.; Bahamonde, A.; Arnaiz delas Revillas, F.; Gomez-Barquero, J.; Abadia-Otero, J.; Garcia-Ibarbia, C.; Mora, V.; Cerezo-Hernández, A.; Hernández, J.L.; López-Muñíz, G.; et al. GLUCOCOVID: A controlled trial of methylprednisolone in adults hospitalised with COVID-19 pneumonia. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2021, 133, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dequin, P.F.; Heming, N.; Meziani, F.; Plantefève, G.; Voiriot, G.; Badié, J.; François, B.; Aubron, C.; Ricard, J.-D.; Ehrmann, S.; et al. Effect of hydrocortisone on 21-day mortality or respiratory support among critically ill patients with COVID-19: A randomised clinical trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edalatifard, M.; Akhtari, M.; Salehi, M.; Naderi, Z.; Jamshidi, A.; Mostafaei, S.; Najafizadeh, S.R.; Farhadi, E.; Jalili, N.; Esfahani, M.; et al. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse as a treatment for hospitalised severe COVID-19 patients: Results from a randomised controlled clinical trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2002808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horby, P.; Lim, W.S.; Emberson, J.R.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Brightling, C.; Ustianowski, A.; Elmahi, E.; et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamaati, H.; Hashemian, S.M.; Farzanegan, B.; Malekmohammad, M.; Tabarsi, P.; Marjani, M.; Moniri, A.; Abtahian, Z.; Haseli, S.; Mortaz, E.; et al. No clinical benefit of high dose corticosteroid administration in patients with COVID-19: A preliminary report of a randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 897, 173947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Yang, M.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Shu, D.; Xia, J.; Liao, X.; Gu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Yang, Y.; et al. Experimental Treatment with Favipiravir for COVID-19: An Open-Label Control Study. Engineering 2020, 6, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemnejad-Berenji, M.; Pashapour, S. Favipiravir and COVID-19: A Simplified Summary. Drug Res. 2020, 71, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coomes, E.A.; Haghbayan, H. Favipiravir, an antiviral for COVID-19? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 2013–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożdżal, S.; Rosik, J.; Lechowicz, K.; Machaj, F.; Kotfis, K.; Ghavami, S.; Łos, M.J. FDA approved drugs with pharmacotherapeutic potential for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) therapy. Drug Resist. Update 2020, 53, 100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Griesel, M.; Mikolajewska, A.; Mueller, A.; Nothacker, M.; Kley, K.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Fischer, A.-L.; Kopp, M.; Stegemann, M.; et al. Systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 8, CD014963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wang, Y.; Wen, D.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Fan, G.; Ruan, L.; Song, B.; Cai, Y.; Wei, M.; et al. A Trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horby, P.W.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Emberson, J.; Palfreeman, A.; Raw, J.; Elmahi, E.; Prudon, B.; et al. Lopinavir–ritonavir in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Shang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, M.; Hong, Z.; et al. Efficacy of chloroquine versus lopinavir/ritonavir in mild/general COVID-19 infection: A prospective, open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled clinical study. Trials 2020, 21, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, Y.M.; Gordon, A.C.; Derde, L.P.G.; Nichol, A.D.; Murthy, S.; Al Beidh, F.; Annane, D.; Al Swaidan, L.; Beane, A.; Beasley, R.; et al. Lopinavir-ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine for critically ill patients with COVID-19: REMAP-CAP randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, S.; Fard, S.R.; Maleki, D.; Taher, M.T.; Yassin, Z.; Alimohamadi, Y.; Minaeian, S. Comparing the effectiveness of Atazanavir/Ritonavir/Dolutegravir/Hydroxychloroquine and Lopinavir/Ritonavir/Hydroxychloroquine treatment regimens in COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 6557–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, G.; dos Santos Moreira Silva, E.A.; Medeiros Silva, D.C.; Thabane, L.; Singh, G.; Park, J.J.H.; Forrest, J.I.; Harari, O.; Quirino Dos Santos, C.V.; Guimarães de Almeida, A.P.F.; et al. Effect of Early Treatment with Hydroxychloroquine or Lopinavir and Ritonavir on Risk of Hospitalization Among Patients With COVID-19: The TOGETHER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e216468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.; Chan-Tack, K.; Farley, J.; Sherwat, A. FDA Approval of Remdesivir—A Step in the Right Direction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2598–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, D.; Hui, H.C.; Doerffler, E.; Clarke, M.O.; Chun, K.; Zhang, L.; Neville, S.; Carra, E.; Lew, W.; Ross, B.; et al. Discovery and Synthesis of a Phosphoramidate Prodrug of a Pyrrolo[2,1-f][triazin-4-amino] Adenine C-Nucleoside (GS-5734) for the Treatment of Ebola and Emerging Viruses. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1648–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kokic, G.; Hillen, H.S.; Tegunov, D.; Dienemann, C.; Seitz, F.; Schmitzova, J.; Farnung, L.; Siewert, A.; Höbartner, C.; Cramer, P. Mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase stalling by remdesivir. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Mu, A.; Ji, W.; Yan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, C.; et al. Structural Basis for RNA Replication by the SARS-CoV-2 Polymerase. Cell 2020, 182, 417–428.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Feng, J.Y.; Porter, D.P.; Götte, M. The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 4773–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tchesnokov, E.P.; Feng, J.Y.; Porter, D.P.; Götte, M. Mechanism of Inhibition of Ebola Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase by Remdesivir. Viruses 2019, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bouvet, M.; Imbert, I.; Subissi, L.; Gluais, L.; Canard, B.; Decroly, E. RNA 3′-end mismatch excision by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein nsp10/nsp14 exoribonuclease complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9372–9377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robson, F.; Khan, K.S.; Le, T.K.; Paris, C.; Demirbag, S.; Barfuss, P.; Rocchi, P.; Ng, W.-L. Coronavirus RNA Proofreading: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Targeting. Mol. Cell 2020, 79, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Graham, R.L.; Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Case, J.B.; Leist, S.R.; Pyrc, K.; Feng, J.Y.; Trantcheva, I.; et al. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Warren, T.K.; Jordan, R.; Lo, M.K.; Ray, A.S.; Mackman, R.L.; Soloveva, V.; Siegel, D.; Perron, M.; Bannister, R.; Hui, H.C.; et al. Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature 2016, 531, 381–385, Erratum in 2016, 11, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Mylonakis, E. In inpatients with COVID-19, none of remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, or interferon β-1a differed from standard care for in-hospital mortality. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, JC17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beigel, J.H.; Tomashek, K.M.; Dodd, L.E.; Mehta, A.K.; Zingman, B.S.; Kalil, A.C.; Hohmann, E.; Chu, H.Y.; Luetkemeyer, A.; Kline, S.; et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of COVID-19—preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Du, G.; Du, R.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Y.; Fu, S.; Gao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Lu, Q.; et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, W.P.; Holman, W.; Bush, J.A.; Almazedi, F.; Malik, H.; Eraut, N.C.J.E.; Morin, M.J.; Szewczyk, L.J.; Painter, G.R. Human Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Molnupiravir, a Novel Broad-Spectrum Oral Antiviral Agent with Activity against SARS-CoV-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02428-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, B.; Campbell, E.A. Molnupiravir: Coding for catastrophe. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021, 28, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e935952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muramatsu, T.; Takemoto, C.; Kim, Y.-T.; Wang, H.; Nishii, W.; Terada, T.; Shirouzu, M.; Yokoyama, S. SARS-CoV 3CL protease cleaves its C-terminal autoprocessing site by novel subsite cooperativity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12997–13002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiong, M.; Su, H.; Zhao, W.; Xie, H.; Shao, Q.; Xu, Y. What coronavirus 3C-like protease tells us: From structure, substrate selectivity, to inhibitor design. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 1965–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabati, M.; Parsaee, H. Potential Cardiotoxic Effects of Remdesivir on Cardiovascular System: A Literature Review. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2021, 13, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Osborne, V.; Lane, S.; Roy, D.; Dhanda, S.; Evans, A.; Shakir, S. Remdesivir in Treatment of COVID-19: A Systematic Benefit–Risk Assessment. Drug Saf. 2020, 43, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parham, W.A.; Mehdirad, A.A.; Biermann, K.M.; Fredman, C.S. Case report: Adenosine induced ventricular fibrillation in a patient with stable ventricular tachycardia. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2001, 5, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, C.A.; Qureshi, N.; Ng, F.S.; Panoulas, V.F.; Lim, P.B. Adenosine induced ventricular fibrillation in a structurally normal heart: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chow, E.J.; Maust, B.; Kazmier, K.M.; Stokes, C. Sinus Bradycardia in a Pediatric Patient Treated with Remdesivir for Acute Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Case Report and a Review of the Literature. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2021, 10, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Shin, J.S.; Park, S.-J.; Jung, E.; Park, Y.-G.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.J.; Park, H.-J.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, S.-M.; et al. Antiviral activity and safety of remdesivir against SARS-CoV-2 infection in human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Antivir. Res. 2020, 184, 104955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulangu, S.; Dodd, L.E.; Davey, R.T., Jr.; Tshiani Mbaya, O.; Proschan, M.; Mukadi, D.; Lusakibanza Manzo, M.; Nzolo, D.; Tshomba Oloma, A.; Ibanda, A.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Ebola Virus Disease Therapeutics. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, J.; Du, R.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Gao, L.; Jin, Y.; Luo, G.; et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of intravenous remdesivir in adult patients with severe COVID-19: Study protocol for a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Trials. 2020, 21, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Li, H.; Lee, K.H.; Koyanagi, A.; Solmi, M.; Kronbichler, A.; Dragioti, E.; Tizaoui, K.; Cargnin, S.; et al. Cardiovascular events and safety outcomes associated with remdesivir using a World Health Organization international pharmacovigilance database. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M. Cardiovascular health and protection against CVD: More than the sum of the parts? Circulation 2014, 130, 1671–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Ongoing Safety Review of Invirase (Saquinavir) and Possible Association with Abnormal Heart Rhythms. 23 February 2010. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/fda-drug-safety-communication-ongoing-safety-review-invirase-saquinavir-and-possible-association (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Beyls, C.; Martin, N.; Hermida, A.; Abou-Arab, O.; Mahjoub, Y. Lopinavir-Ritonavir Treatment for COVID-19 Infection in Intensive Care Unit. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e008798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, J.; Caro, J.; Rey, J.; Castrejon, S.; Martinez-Cossiani, M. Cardiac arrhythmias in COVID-19: Mechanisms, outcomes and the potential role of proarrhythmia. Europace 2021, 23, euab116.115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, V.; Dow, P.; Al Rihani, S.B.; Deodhar, M.; Arwood, M.; Cicali, B.; Turgeon, J. Risk Assessment of Drug-Induced Long QT Syndrome for Some COVID-19 Repurposed Drugs. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 14, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Agarwal, S.K. Lopinavir-Ritonavir in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Drug-Drug Interactions with Cardioactive Medications. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2020, 35, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, I.; Alvarez, H.; Mariño, A.; Clotet, B.; Molto, J. Recurrent coronary disease in HIV-infected patients: Role of drug-drug interactions. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1617–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancrenaz, V.; Déglon, J.; Samer, C.; Staub, C.; Dayer, P.; Daali, Y.; Desmeules, J. Pharmacokinetic Interaction Between Prasugrel and Ritonavir in Healthy Volunteers. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012, 112, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daali, Y.; Ancrenaz, V.; Bosilkovska, M.; Dayer, P.; Desmeules, J. Ritonavir inhibits the two main prasugrel bioactivation pathways in vitro: A potential drug–drug interaction in HIV patients. Metabolism 2011, 60, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtenbaum, C.J.; Gerber, J.G.; Rosenkranz, S.L.; Segal, Y.; Aberg, J.A.; Blaschke, T.; Alston, B.; Fang, F.; Kosel, B.; Aweeka, F. Pharmacokinetic interactions between protease inhibitors and statins in HIV seronegative volunteers: ACTG Study A5047. AIDS 2002, 16, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueck, W.; Kubitza, D.; Becka, M. Co-administration of rivaroxaban with drugs that share its elimination pathways: Pharmacokinetic effects in healthy subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 76, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeh, R.F.; Gaver, V.E.; Patterson, K.B.; Rezk, N.L.; Baxter-Meheux, F.; Blake, M.J.; Eron, J.J.; Klein, C.E.; Rublein, J.C.; Kashuba, A.D. Lopinavir/Ritonavir Induces the Hepatic Activity of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP1A2 But Inhibits the Hepatic and Intestinal Activity of CYP3A as Measured by a Phenotyping Drug Cocktail in Healthy Volunteers. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006, 42, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- NORVIR (Ritonavir). Summary of Product Characteristics. 26 August 1996 (revised 17 January 2013). Abbott Laoratories Limited, Abbott House, Maidenhead, Berkshire. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/norvir-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Macchiagodena, M.; Pagliai, M.; Procacci, P. Characterization of the non-covalent interaction between the PF-07321332 inhibitor and the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2021, 110, 108042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, N.W.; Salerno, D.M.; Jennings, D.L.; Choe, J.; Hedvat, J.; Kovac, D.; Scheffert, J.; Shertel, T.; Ratner, L.E.; Brown, R.S.; et al. Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir use: Managing clinically significant drug-drug interactions with transplant immunosuppressants. Am J. Transplant. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, T.J.; Mohiddin, S.A.; DiMarco, A.; Patel, V.; Savvatis, K.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; Madhur, M.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; Maffia, P.; D’Acquisto, F.; et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: Implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1666–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmati, D.; Bramanti, B.; Serino, M.L.; Secchiero, P.; Zauli, G.; Tisato, V. COVID-19 and Individual Genetic Susceptibility/Receptivity: Role of ACE1/ACE2 Genes, Immunity, Inflammation and Coagulation. Might the Double X-chromosome in Females Be Protective against SARS-CoV-2 Compared to the Single X-Chromosome in Males? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zores, F.; Rebeaud, M.E. COVID and the Renin-Angiotensin System: Are Hypertension or Its Treatments Deleterious? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasoni, D.; Italia, L.; Adamo, M.; Inciardi, R.M.; Lombardi, C.M.; Solomon, S.D.; Metra, M. COVID-19 and heart failure: From infection to inflammation and angiotensin II stimulation. Searching for evidence from a new disease. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2020, 22, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Poglitsch, M.; Yogasundaram, H.; Thomas, J.; Rowe, B.H.; Oudit, G.Y. Roles of Angiotensin Peptides and Recombinant Human ACE2 in Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coromilas, E.J.; Kochav, S.; Goldenthal, I.; Biviano, A.; Garan, H.; Goldbarg, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Yeo, I.; Tracy, C.; Ayanian, S.; et al. Worldwide Survey of COVID-19–Associated Arrhythmias. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2021, 14, e009458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. SARS-CoV-2 infection and venous thromboembolism after surgery: An international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia 2022, 77, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative Effects of pre-operative isolation on postoperative pulmonary complications after elective surgery: An international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 1454–1464. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappi, F.; Iervolino, A.; Avtaar Singh, S.S. Thromboembolic Complications of SARS-CoV-2 and Metabolic Derangements: Suggestions from Clinical Practice Evidence to Causative Agents. Metabolites 2021, 11, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, F. Incertitude Pathophysiology and Management During the First Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 113, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: An international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. GlobalSurg Collaborative SARS-CoV-2 vaccination modelling for safe surgery to save lives: Data from an international prospective cohort study. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 108, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).