Abstract

Background: Health literacy can impact comprehension, recall, and implementation of stroke-related information, especially in the context of cognitive and communication impairments, cultural-linguistic diversity, or ageing. Yet there are few published lived experience perspectives to inform tailoring of health information. Objectives: We aimed to (i) explore perspectives about the impact of health literacy on information needs and preferences of stroke survivors with diverse characteristics; and (ii) identify ways to better tailor information delivery for stroke survivors with low health literacy. Methods: This qualitative study was conducted using the Ophelia (Optimising Health Literacy and Access) methodology. First, health literacy information was collected from participants. Hierarchical cluster analysis was used to identify different health literacy profiles within the participant sample. Four profiles were identified, from which four case vignettes were created. Second, focus groups and interviews were conducted to explore the health information needs and preferences of the case vignettes. Qualitative data were analysed with reflexive thematic analysis. Results: Nineteen people participated (median (IQR) age = 65 (49, 69), 10 (53%) female); five used interpreters. Participants represented diverse socioeconomic, cultural, and stroke-related characteristics, and generally had low health literacy. Four qualitative themes were generated highlighting the impact of Individual knowledge, capacity, and beliefs about stroke and health services on people’s capacity to engage with stroke-related information; Tailoring and personalisation of information delivery to the patient’s knowledge, capacity, and beliefs; Having a support network to rely on; and patients Feeling like I am in safe hands of clinicians and services. Conclusions: Findings provide several important directions for improving accessible stroke information delivery suitable for people with all levels of health literacy, and to optimise patient understanding, recall, and implementation of healthcare information.

1. Introduction

Low health literacy, defined as people’s ability to seek, understand, engage with, and implement health information, is surprisingly prevalent in the general community. Only 41% of Australian adults have sufficient health literacy to understand and use health information [1,2]. Low health literacy is particularly common in people with older age, limited education, and in some culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations AIHW [2,3]. One in two people with stroke experience cognitive impairment and one in four have communication impairments [4]. This can further compromise health literacy and affect comprehension, recall, and effective implementation of health-related information [5,6]. With low health literacy impacting poorer stroke outcomes including medication adherence, general health status, and hospital readmission [7], it is incumbent on health practitioners to provide appropriate health information to support stroke recovery

Organisational literacy, or the health literacy environment, is the degree to which organisations can acknowledge and accommodate variations in patient health literacy and thereby support patients to manage their health and navigate the health system. Proponents of improving organisational literacy, rather than attempting to improve health literacy, support a “universal precautions” approach to heath communication. Such an approach requires habitual use of clear communications to improve accessibility of health information for all people with stroke, regardless of their health literacy [8]. This shifts the onus of responsibility from the marginalised patient to that of the health service to provide appropriately tailored stroke care [9]. Health services have a responsibility to support health literacy [10]; however, to date there is limited evidence that this occurs consistently in clinical practice. A recent qualitative study of Australian stroke clinicians found that only 60% had received training to support their communication with people with aphasia [11], and there are gaps between clinicians’ theoretical understanding of information provision and their actual practice [12]. Although there are lived experience-informed guidelines for the provision of information for people with stroke [13], adult learning principles are not always applied by health professionals when providing information [14], and the reading level of many stroke education materials is too high [15].

Poor organisational health literacy can lead to poor experiences of healthcare and poor outcomes post-stroke [2]. Therefore, it is incumbent upon stroke services to improve their awareness of and responsiveness to low health literacy in their service users. To do this, it is important to include the voices of people with lived experience of stroke to ensure that service improvements reflect the values and needs of patients. In particular, it is important to include the voices of people with cognitive and communication difficulties, limited education, and those from CALD backgrounds, given their increased likelihood of low health literacy and their frequent exclusion from stroke research [16].

Our study had two main aims. Firstly, we aimed to explore stroke survivors’ perspectives on health literacy and how it may impact the information needs and preferences of people with stroke, including people typically under-represented in stroke research. Secondly, we aimed to identify targets or directions for improving organisational literacy—i.e., ways to enable stroke services to better tailor information delivery to stroke survivors with low health literacy, and therefore support their patients to understand and use stroke information to optimise their outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This qualitative study was conducted in two stages using the Ophelia (Optimising Health Literacy and Access) methodology [17]. In Stage 1, health literacy information was collected from participants to create case vignettes that represented their common characteristics. In Stage 2, focus groups and interviews were conducted about the health information needs and preferences of the people described in the case vignettes. This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled “When the Word is Too Big, it’s Just Too Hard: How can Clinicians Support Patients’ Health Literacy to Improve Recovery after Stroke?”, which was presented at Stroke 2023, Melbourne, Australia, in August 2023 [18].

2.1. Participants

Inclusion criteria for the study were community-dwelling adults (≥18 years old) with stroke or transient ischemic attack who attended St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne (SVHM) outpatient stroke clinic between January 2021 and February 2022. SVHM is a public tertiary hospital in inner Melbourne that caters to a broad demographic of the local multicultural community.

Clinic lists were screened by clinician researchers (CF and LS) and consecutive, eligible participants were invited to participate via a telephone call or discussion during a stroke clinic appointment. Purposeful recruitment was undertaken to include people whose preferred language was not English (especially people from Vietnamese background as this population was a common user group of interpreter services at SVHM). Potential participants identified as likely to have aphasia, cognitive impairment, or low English literacy were offered an Assisted Communication or Easy English version of the Patient Information and Consent Form, with use of interpreters when required. Participants were made aware that this research was being conducted with aim of improving stroke services at SVHM. Further information about the research teams’ interest in the topic was discussed according to patient interest. Participant recruitment was limited by strict and prolonged COVID-19 related lockdowns in Melbourne during the data collection period.

2.2. Materials and Procedures

Materials were developed and pilot tested by the multidisciplinary research team, who had extensive research and clinical experience in stroke recovery, supported communication (for post-stroke aphasia and cognition difficulties), health literacy, and interpreter services, and lived experience of stroke.

2.2.1. Stage 1

Electronic health records were reviewed to collect patient data relating to demographics (gender, age, languages spoken, highest level of education, birth country, living arrangements, carer support), clinical details of stroke including any description or assessment of language impairment, communication support needs and cognition, and global disability (modified Rankin score, mRS). Education level was classified as follows: did not complete primary school, completed primary school, completed secondary school, certificate/apprenticeship/diploma, degree, or post-graduate qualification. Observed communication or cognition impairments were also noted during participant interviews that were conducted by researcher CF, an experienced stroke clinician.

Socioeconomic status was categorised based on postcode of home address using the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage, (1 = most disadvantaged, 5 = most advantaged) ABS [19]. Lower scores indicate relatively greater disadvantage and a lack of advantage in general. For example, an area could have a low score if there are many households with low incomes, or many people in unskilled occupations, and a few households with high incomes, or few people in skilled occupations.

Structured interviews, developed collaboratively by the research team, were conducted to collect information not available in medical records, and participant data relating to health literacy, global disability (modified Rankin score, mRS), stroke-related information needs, and knowledge of stroke and secondary stroke prevention. Interviews were undertaken in person, via telephone or via telehealth, depending on patient preference and COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Interviews were conducted by author CF (an experienced stroke clinician and researcher) between December 2021 and March 2022. Interpreters were used as required. Participants were offered breaks during the interview and interviews were conducted across two sessions, if needed.

Formal cognitive assessment using the Oxford Cognitive Screen (Australian version, OCS-AU) was planned; however, due to challenges with telehealth administration during the pandemic, this was not conducted.

Health literacy was evaluated using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) [20] and the Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool (BRIEF) [21]. The HLQ measures health literacy across nine independent scales, each measuring a different aspect of health literacy. The HLQ is considered highly reliable (composite reliability ranges from 0.8 to 0.9) [22] and is widely used, including in populations with cardiovascular disease [23]. Five HLQ scales were used for this study: Scale 2, Having sufficient information to manage my health; Scale 3, Actively managing my health; Scale 4, Social support for health; Scale 6, Ability to actively engage with healthcare providers; and Scale 7, Navigating the healthcare system. Scales 2, 3, and 4 are answered using a 4-point Likert scale (range 1–4) and scales 6 and 7 answered using a 5-point Likert scale (range 1–5). The Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool (BRIEF) [24] is a 4-item measure (range 1–20) that captures people’s functional health literacy (i.e., the ability to read and understand written information). The instrument has been widely used across different health conditions, including stroke [25].

2.2.2. Stage 2

Using HLQ data collected in Stage 1, four different groupings (“clusters”) of participants were identified, each representing a different health literacy profile within the sample (see Section 2.3 for detail). Brief case vignettes were then developed representing the four participant clusters. An example vignette is contained in Table 1; the remaining three vignettes are Supplementary Files. The vignettes were then used to guide discussions in the Stage 2 focus groups and interviews.

Table 1.

Case vignette example: Character “Mai”.

Participants were invited to attend small focus groups. Focus groups were conducted in June 2022 via Zoom by DW (experienced clinical neuropsychologist, group facilitator, and qualitative researcher), AB (experienced health literacy researcher), and CF (clinician researcher), all of whom are female. Each group commenced with a brief introduction about the interviewing team and the aims of the project, which were (1) to improve the way stroke services were delivered at both SVHM and more broadly, and (2) to make it easier for survivors of stroke to understand and use information about their health. Participants were also provided with the opportunity to introduce themselves. Using PowerPoint slides and a verbal description, participants were presented with 1–2 vignettes (see Table 1) which best represented the experiences of the group. Participants were then asked a series of questions about how stroke services could meet the needs of the ”character” in the vignette. Questions included (i) “Does this sound like someone you know, or something you may have experienced?”, (ii) “What things might make it difficult for [character] to find, understand, and use information about [their] stroke?”, (iii) “What strengths does she have to help her make changes?”, and (iv) “What could our health service do to make things easier/better for [character]?” The group facilitators encouraged all participants to share their views and ensured that everyone had the chance to do so either verbally or in the Zoom chat. Communication support strategies, such as slowed pace of speech, repetition, paraphrasing, and reflective summaries of participants’ comments to confirm their meaning, were used by facilitators as required. Interviewers made notes during discussions, and a summary of participant comments was then shown on a slide for participants to confirm that the summary accurately described their views.

For participants who indicated that participation in focus groups was too challenging, individual semi-structured interviews were undertaken via Zoom or telephone by author CF with an interpreter when required. Duration ranged from 15 to 60 min. For telephone interviews, a spoken description of the vignettes was provided and similar questions to that of the focus groups described above used as prompts to elicit information.

Audio from each focus group and interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim. If the participant did not wish to be recorded, a written summary of their interview was taken.

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Stage 1

Data related to individual participants’ demographics, health literacy, and stroke-related information needs were analysed descriptively. STATA version 15 [26] and SPSS version 22 [27] were used for analyses of quantitative data. A p-value of <0.05 was assumed for statistical significance. Hierarchical cluster analysis was used to identify different health literacy profiles within the patient sample using Ward’s method for linkage [28]. Based on previous work [17], a range of cluster solutions of between 2 and 8 clusters was pre-determined. Selection of the most appropriate cluster solution was based on two criteria: first, whether the standard deviation within each scale within each cluster was below 0.6; and second, whether distinct patterns of HLQ scale scores were seen between clusters. Demographic, clinical, and health data were reported for each cluster, providing a detailed picture of a “typical” person within that cluster.

2.3.2. Stage 2

The focus groups and interviews were transcribed and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis [29,30]. A critical realist approach to analysis was taken, seeking to understand the meaning participants made of their experiences (via the case vignettes) and the influence of broader social and structural contexts, within the shared context of engaging with health services following a stroke. Data were coded through a process of familiarisation (rereading the transcripts several times), then generating initial codes based on both verbatim utterances and underlying patterns and concepts, and constantly revisiting the transcripts as the codes were refined. Generation and refinement of codes was conducted by researcher ES (research assistant with Honours-level training in psychology) in consultation with DW, using NVivo 1.7.1. The research team (CF, CH, DW, ES, KB) then collaboratively grouped the codes and generated themes during a Zoom meeting using Ideaflip online software (ideaflip.com). Themes were defined and labelled, and relationships between themes were explored together as a team.

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1

Nineteen participants completed structured interviews in Stage 1. Participants were interviewed via telephone (n = 16) in their homes or local communities, face to face (n = 2) in the stroke clinic or via Zoom (n = 1) in their home. Interpreters were utilised in five interviews. Family members were present for all face to face, Zoom, and interpreter interviews. It is unknown if anyone else was present during telephone calls conducted in English.

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 2. The median (IQR) age of participants was 65 (49, 69) years, 10 (53%) were female and 9 (47%) were male, and 9 (47%) completed education beyond high school. Eleven participants (58%) resided in areas of the highest socioeconomic category, and two (11%) resided in the lowest category. Eleven participants (58%) were born in Australia, and the remainder in Asia or Europe. Five participants (26%) spoke Vietnamese, and all used interpreters during their interviews. The remaining 14 people were interviewed in English without interpreters. The median time post-stroke was 9.5 months (IQR 6, 14). As mentioned, cognitive assessment could not be completed, and medical records generally had no record of cognitive status. Cognitive impairment was noted for six (32%) participants; three of these by the researcher based on clinical impression, and three by the family (clinical impression was more difficult for these participants due to use of an interpreter). Seven (37%) participants had mild communication impairments at the time of stroke (NIHSS 1–3 for aphasia or dysarthria). All participants completed the interviews independently, without carer support or personalised communication support.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics.

HLQ data approximated normal distribution, and homogeneity of variance was not violated. Mean HLQ scores are shown in Table 3. For scales 2, 3, and 4 (maximum possible score 4.00), the lowest score was seen for scale 2, Having sufficient information to manage my health (mean score 2.67, SD 0.76). For scales 6 and 7 (maximum possible score 5.00), the lowest mean score was for scale 7, Navigating the healthcare system (mean score 3.38, SD 1.01). For the BRIEF, median score was 12 (inter-quartile range 8, 19) from a possible range of 4–20.

Table 3.

Health literacy scores for the sample.

From the cluster analysis of HLQ data, four distinct profiles were identified, representing a diversity of health literacy strengths and weaknesses, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Cluster analysis, reporting HLQ and BRIEF scores only.

3.2. Stage 2

Ten participants from the Stage 1 cohort participated in Stage 2. Nine people declined to participate in Stage 2 (carer responsibilities n = 1; time constraints n= 4; no longer wished to participate n= 1; new illness n = 1; unable to be contacted n = 2). Of those who participated in Stage 2, 6 (60%) were female and 4 (40%) male, median (IQR) age = 57 (38, 65); time since stroke = 10 (7, 14) months, and 7 (70%) completed education beyond high school). One participant in Stage 2 spoke Vietnamese and completed the interview with an interpreter. Four people (40%) were identified as having cognitive impairment, and three (30%) had communication impairment. The rates of cognitive and communication impairments noted in the group of people who did not complete Stage 2 were 2/9 (22%) and 4/9 (44%), respectively.

Two 90 min focus groups were undertaken, each with three participants. Four individual interviews were undertaken via telephone (n = 3) or Zoom (n = 1). Due to time constraints and the rich discussion generated by the vignettes, no participants were presented with all four vignettes. All focus group participants were presented with one vignette. Two interview participants were presented with one vignette, one interview participant was presented with two vignettes, and one participant did not wish to hear the vignette and was interviewed about their own experiences. One participant did not wish to be recorded, so instead a summary of their interview was written by the researcher. Despite the attrition between Stage 1 and 2 of the study, we deemed theoretical sufficiency [31] to be achieved after 10 interviews.

Reflexive Thematic Analysis Findings

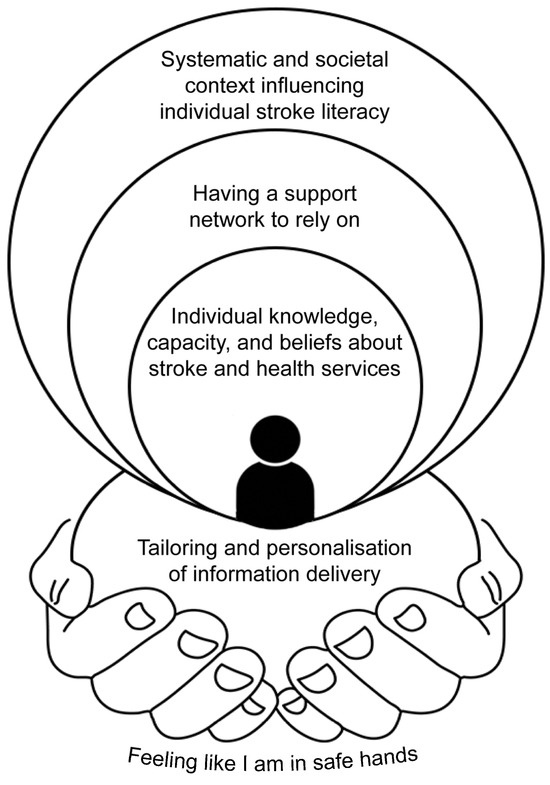

As depicted in Figure 1, four themes and one subtheme were generated about health literacy needs and preferences of stroke survivors, and how cognitive difficulties, communicative difficulties, and culture may affect these needs and preferences. The first theme, “Individual knowledge, capacity, and beliefs about stroke and health services”, considers the individual characteristics, history, and worldview of the patient, and the subtheme, “Systemic and societal context influencing individual stroke literacy”, considers the influence of the patient’s context on their individual knowledge, capacity, and beliefs about stroke and health services. The second theme, “Tailoring and personalisation of information delivery”, considers the characteristics of the healthcare information presented to the patient, its delivery to the patient, and the value of tailoring information and delivery to the patient based on their knowledge, capacity, and beliefs. The third theme, “Having a support network to rely on”, considers the multifaceted roles of support people in facilitating access to healthcare information and supporting patients to implement healthcare recommendations. The final theme, “Feeling like I am in safe hands”, considers the extent to which the patient trusts and is confident in the quality of care they receive from clinicians and services. Feeling in safe hands is influenced by the patient’s knowledge, capacity, and beliefs (Theme 1), the extent to which information delivery is tailored to their needs (Theme 2), and the interactions of their support network, clinicians, and services (Theme 3). Each of these themes influences understanding, recall, and implementation of healthcare information by the patient.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the themes and relationship between them.

Theme 1: Individual knowledge, capacity, and beliefs about stroke and health services. This theme pertains to the influence of individual knowledge, beliefs, strengths, and challenges on how patients make sense of their stroke journey and health information. This theme also contains a subtheme, Systemic and societal context influencing individual stroke literacy. Table 5 describes the key concepts reflected in Theme 1 and its subtheme, and provides illustrative quotes.

Table 5.

Descriptions of key concepts and illustrative quotes for Theme 1, “Individual knowledge, capacity, and beliefs about stroke and health” and its subtheme, “Systemic and societal context influencing individual stroke literacy”.

Theme 2: Tailoring and personalisation of information delivery. This theme highlights the importance of delivering healthcare information in a manner that is relevant and meaningful for each individual patient. There is no “one size fits all” approach, so healthcare providers need to use a range of strategies to meet the needs and preferences of individual patients. As outlined in Table 6, participants stressed the importance of tailoring information delivery to their needs, knowledge, capacity, and beliefs. When materials, resources, and information delivery are appropriate to the needs and capacity of the stroke survivor, they support the understanding, recall, and implementation of healthcare information. Specific suggestions made by participants for support materials and information delivery methods are listed in Table 7.

Table 6.

Descriptions of key concepts and illustrative quotes for Theme 2, “Tailoring and personalisation of information delivery”.

Table 7.

Recommendations from participants about tailoring and personalising delivery of information for people with stroke.

Theme 3: Having a support network to rely on. This theme identifies the importance of having access to friends, family, and services to assist in understanding, recalling, and implementing healthcare information. As shown in Table 8, supportive friends and family were crucial allies for participants at every stage of the stroke journey, from the acute stage to ongoing chronic care. They helped the participants to feel cared for, that there was someone with whom to share the difficult experiences, and that empowered them to understand and respond to health information together.

Table 8.

Descriptions of key concepts and illustrative quotes for Theme 3, “Having a support network to rely on”.

Theme 4: Feeling like I am in safe hands. This theme highlights the importance of having access to effective healthcare services, feeling confident in the quality of care, and feeling safe to speak up and ask questions. When patients feel they are in safe hands, they believe that their healthcare team is competent, trustworthy, and has their best interests at heart, and that they are working together in alliance. This enables participants to better engage with health information. Table 9 describes key concepts important for “feeling like I am in safe hands”.

Table 9.

Descriptions of key concepts and illustrative quotes for Theme 4, “Feeling like I am in safe hands”.

4. Discussion

Using the novel Ophelia (Optimising Health Literacy and Access) methodology, the aim of this study was to explore perspectives on the associations between health literacy and the information needs and preferences of stroke survivors, and identify targets or directions for improving organisational health literacy to better tailor information delivery. Our participants, including people typically under-represented in stroke research (i.e., those from CALD backgrounds, and with cognitive and communication impairments), provided rich insights into the impact of health literacy on their ability to seek, understand, engage with, and act on health information. Four themes were generated in discussions about the four case vignettes used to describe typical health literacy profiles. The first theme highlighted the impact of Individual knowledge, capacity, and beliefs about stroke and health services on their capacity to engage with stroke-related information. The second theme, Tailoring and personalisation of information delivery, pointed to the importance of accessible healthcare information delivered in a manner that is tailored to the patient’s knowledge, capacity, and beliefs—rather than adopting a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Thirdly, Having a support network to rely on emphasised the multifaceted roles of family and other support people in facilitating access to, comprehension of, and implementation of healthcare information. Finally, Feeling like I am in safe hands described the importance of patient trust and confidence in the quality of care they receive from clinicians and services. Our findings provide several important directions for improving organisational literacy to optimise understanding, recall, and implementation of healthcare information by the patient, and therefore their healthcare experiences and outcomes.

Health literacy scores of participants in Stage 1 were generally low. Participants were fairly typical of SVHM patients, with 42% born outside Australia and 26% speaking a language other than English (i.e., Vietnamese), requiring an interpreter. During the study year, 48% of all patients admitted to the stroke unit at SVHM were born in a country other than Australia (compared with 31% nationally) and 18% spoke languages other than English (compared with 8% nationally) [32]. Despite most participants being more than six months post-stroke, health literacy scores were lowest for “having sufficient information to manage my health” and “navigating the healthcare system”. This is consistent with previous research where stroke survivors and care givers report receiving an inadequate amount of information, or receiving information at an inappropriate time, or stroke survivors not recalling information provided [33].

These findings reinforce the need for clinicians to consider all the factors that impact healthcare communication, including health literacy, preferred language, older age, cognition, aphasia and other communication disability, and available support when developing and delivering health information. The subset of participants who completed Stage 2, several of whom had lived experience of these issues, were able to provide simple practical recommendations for clinicians to support people with such challenges (listed in Table 3). They suggested comprehensive consideration of patient characteristics that are likely to impact understanding of and engagement with health information (to address the issues raised in Theme 1); tailoring of information using communication support strategies such as the use of pictures, videos, and gesture to support text and spoken language; and providing notes, handouts, and resource links for patients to refer to outside of clinical appointments (Theme 2). These recommendations are consistent with strategies used in evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation programs [34,35], aphasia-friendly written education materials [36,37], and healthcare communication post-stroke [38].

Efforts to tailor information to patients’ individual health literacy require clinicians to assess and understand, rather than assume, their patients’ prior knowledge, capacity, and beliefs about stroke and health services. Assessment of health literacy goes beyond standard stroke assessment tools, but can be achieved fairly quickly by asking questions such as “What do you understand about stroke?” Similarly, assessment of cognitive and communication support needs is often overlooked in standard stroke care [39,40] and is not captured by commonly used tools that assess functional outcomes such as the modified Rankin scale [41]. In our attempts to purposively recruit participants with cognitive and communication impairments for this study, we found that mRS scores were not helpful indicators of these difficulties, and there was typically limited identification of cognitive or communication issues in health records. This suggests that indicators of challenges to health literacy may be “flying under the radar”, precluding the opportunity to adequately tailor healthcare communication.

Medical, nursing, and allied health professionals also require training and competencies in how to adapt their communication for people with cognitive impairment [35] and aphasia [42]. Examples of free training include Stroke Foundation [43] and Aphasia Institute [44]. This is often overlooked in training programs [38]. Simply presenting standard information is not sufficient for patients to understand and implement it. Developing clear competency frameworks and associated training protocols to support communication of health information for people with low health literacy is a priority for future research. These protocols should also encourage clinicians to develop a communication style that engenders trust and confidence in their patients. “Feeling like they are in safe hands” (Theme 4) was considered critical by our participants for supporting their engagement with health information and feeling safe to ask questions.

Given the importance of support networks in facilitating access to healthcare information (as reflected in Theme 3), stroke survivors who do not have family members or close others available to support them require clinicians to take extra steps to ensure they understand and feel safe. The subtheme we identified on the Systemic and societal context influencing individual stroke literacy also highlights that improving stroke literacy and reducing stigma in the broader community is likely to positively impact people’s experiences of stroke. This points to the importance of community awareness initiatives, not just about early stroke signs (e.g., F.A.S.T) but also campaigns that include information about life after stroke, especially “invisible” difficulties such as fatigue, cognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety, which are commonly overlooked and misunderstood [39,40]. Including people with lived experience as partners in teams dedicated to health service design and public health campaigns can be an effective strategy that enables the needs of people with stroke to be considered.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. Firstly, there was almost 50% participant attrition between Stage 1 and 2 of the project, particularly of people born outside Australia who spoke Vietnamese and required an interpreter. Of interest, a larger proportion of people who completed both stages were noted to have cognitive impairment than those who did not complete Stage 2 (40% vs. 22%), but fewer had communication impairment (30% vs. 44%), though numbers were small. There were several stated reasons for not participating in Stage 2, but these did not always reflect the extra challenge involved in participating in research for those who do not speak English, which may have formed a barrier to participation even if not directly stated. Notably, Vietnamese-speaking participants tended to prefer face-to-face interviews, but this was not an option throughout a substantial proportion of the data collection period due to pandemic-related restrictions. This meant that while participants from CALD backgrounds were well represented in Stage 1 (and therefore in the case vignettes), they were not as well represented in the focus groups and interviews, so their perspectives on the delivery of health information for the characters in those vignettes were not as prominent. While we deemed theoretical sufficiency to have been reached after 10 interviews, it remains possible that richer information could be gleaned with a more diverse sample. Future research should address this issue, which should be more feasible outside the context of restrictions preventing face-to-face appointments. Additionally, participants were recruited from one stroke unit in Melbourne, Australia. Perspectives of stroke survivors from other regions of Australia and from different CALD communities around the world would be valuable to include in future research.

While there were concerted efforts to recruit people with cognitive and communication impairments, we hoped to recruit more. These efforts were hampered by the lack of information about cognitive and language abilities in health records. Cognitive and language screening, with clear reporting of any impairments in health records, would be a helpful addition to standard stroke care. We originally planned to conduct formal cognitive assessment with participants; however, this plan was revised in the context of pandemic-related lockdowns, given the challenges of assessing cognition via telehealth. While various sources of information were used to identify possible cognitive impairments, the lack of a consistent formal assessment of cognition limited our understanding of participants’ cognitive capabilities and thus the generalisability of results. Future research should incorporate cognitive and language screening to facilitate purposive recruitment as well as characterise samples and ensure inclusion of people with cognitive and communication impairments in stroke research [16]. At a minimum, screening of self-reported cognitive status (thinking and memory) and its impact on daily life is feasible. The extent and impact of language difficulties can be rated by trained examiners using AusTOMs ratings.

5. Conclusions

Our study provides valuable perspectives from stroke survivors about the impact of health literacy on their needs and preferences about the delivery of health information. Listening to the voices of those who are typically under-represented has allowed us to identify key improvements that would improve stroke service delivery. These include considering health literacy levels of patient populations when developing stroke information resources, and assessment of individuals’ cognitive and communication support needs as standard practice. Training is necessary to support clinician and researcher competencies in tailored healthcare communication. Community awareness initiatives are recommended to improve stroke literacy in the general population. These improvements are feasible—for example, in response to our findings, the stroke team at SVHM ran clinician workshops on health literacy and have adjusted their service model to ensure responsivity to low health literacy. It will be important to evaluate the impact of these and similar other service improvements. Greater awareness of and response to health literacy in stroke services has the potential to improve patient experiences and outcomes of stroke care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13050541/s1, Case Vignettes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: K.B., L.M.S., D.W., A.B., K.D.J., K.M. and C.H.; methodology: K.B., L.M.S., D.W. and A.B.; formal analysis: A.B., C.F., D.W. and E.E.S.; investigation: C.F., A.B. and D.W.; data curation: C.F. and K.B.; writing: D.W., K.B. and E.E.S.; writing—review and editing: all authors; supervision: K.B., L.M.S. and D.W.; project administration: K.B. and C.F.; funding acquisition, K.B. and L.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the St Vincent’s Hospital (Melbourne) Research Endowment Fund under grant number 91960.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of St. Vincent Hospital Melbourne [HREC 140/21], approved on 18 October 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon reasonable request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank participants and their supporters, and Allied Health and stroke team members who contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BRIEF | Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool |

| CALD | culturally and linguistically diverse |

| HLQ | Health Literacy Questionnaire |

| mRS | modified Rankin score |

| Ophelia Methodology | Optimising Health Literacy and Access Methodology |

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. Health Literacy; ABS cat. no. 4233.0; ABS.: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW]. Australia’s Health 2018; AIHW: Darlinghurst, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weterings, R.P.; Kessels, R.P.; de Leeuw, F.E.; Piai, V. Cognitive impairment after a stroke in young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Stroke 2023, 18, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.B.; Chen, Y.L.; Xue, H.P.; Hou, P. Health Literacy Risk in Older Adults with and Without Mild Cognitive Impairment. Nurs. Res. 2019, 68, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, F.A.; Wong, D.; Lawson, D.W.; Withiel, T.D.; Stolwyk, R.J. What are the most common memory complaints following stroke? A frequency and exploratory factor analysis of items from the Everyday Memory Questionnaire-Revised. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 34, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, C.; Arnan, M.; Han, S. A new model for secondary prevention of stroke: Transition coaching for stroke. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C.; Birk, S.; DeVoe, J. Health Literacy and Systemic Racism-Using Clear Communication to Reduce Health Care Inequities. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 753–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.; Santos, A.D.; Leclair, L.; Jones, B.; Ranta, A. Improving Indigenous Stroke Outcomes by Shifting Our Focus from Health to Cultural Literacy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2024, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC]. National Statement on Health Literacy—Taking Action to Improve Safety and Quality; ACSQHC: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Giummarra, M.J.; Power, E.; Stolwyk, R.; Crotty, M.; Parsons, B.; Lannin, N.A.; Shweta Kalyani, K. Health services for young adults with stroke: A service mapping study over two Australian states. Health Soc. Care Community 2024, 2024, 8762322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Gasquoine, S.; Caldwell, S.; Nash, D. Health Professional and Family Perceptions of Post-Stroke Information. Nurs. Prax. New Zealand 2015, 31, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, A.; Brown, L.; Smith, J.; House, A.; Knapp, P.; Wright, J.J.; Young, J. Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, Cd001919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, E.A.; Nolan, J.; Bulto, L.N.; Mitchell, J.; McGrath, A.; Lane, S.; Harvey, G.; Cadilhac, D.A.; Harling, R.; Godecke, E. Is learning being supported when information is provided to informal carers during inpatient stroke rehabilitation? A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 3913–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, N.; Tregobov, N.; Kooij, K.; Harris, D.; Goel, G.; Poureslami, I. Health literacy and health outcomes in stroke management: A systematic review and evaluation of available measures. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 5, 172–191. [Google Scholar]

- Shiggins, C.; Ryan, B.; Dewan, F.; Bernhardt, J.; O’Halloran, R.; Power, E.; Lindley, R.I.; McGurk, G.; Rose, M.L. Inclusion of People With Aphasia in Stroke Trials: A Systematic Search and Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 105, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, A.; Batterham, R.W.; Dodson, S.; Astbury, B.; Elsworth, G.R.; McPhee, C.; Jacobson, J.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R.H. Systematic development and implementation of interventions to OPtimise Health Literacy and Access (Ophelia). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.; Smith, E.; Beauchamp, A.; Formby, C.; Sanders, L.; De Jongh, K.; Hansen, C.; McKinley, K.; Cording, A.; Borschmann, K. When the Word is Too Big, it’s Just Too Hard: How can Clinicians Support Patients’ Health Literacy to Improve Recovery after Stroke? In Proceedings of the Stroke 2023, Melbourne, Australia, 22–25 August 2023; pp. 3–78. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/socio-economic-indexes-areas-seifa-australia/latest-release (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Osborne, R.H.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hawkins, M.; Buchbinder, R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, L.D.; Bradley, K.A.; Boyko, E.J. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam. Med. 2004, 36, 588–594. [Google Scholar]

- Elsworth, G.R.; Beauchamp, A.; Osborne, R.H. Measuring health literacy in community agencies: A Bayesian study of the factor structure and measurement invariance of the health literacy questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaby, A.; Friis, K.; Christensen, B.; Rowlands, G.; Maindal, H.T. Health literacy is associated with health behaviour and self-reported health: A large population-based study in individuals with cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1880–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haun, J.; Luther, S.; Dodd, V.; Donaldson, P. Measurement variation across health literacy assessments: Implications for assessment selection in research and practice. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17 (Suppl. 3), 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towfighi, A.; Cheng, E.M.; Ayala-Rivera, M.; Barry, F.; McCreath, H.; Ganz, D.A.; Lee, M.L.; Sanossian, N.; Mehta, B.; Dutta, T.; et al. Effect of a coordinated community and chronic care model team intervention vs usual care on systolic blood pressure in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: The SUCCEED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2036227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Batterham, R.W.; Buchbinder, R.; Beauchamp, A.; Dodson, S.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. The OPtimising HEalth LIterAcy (Ophelia) process: Study protocol for using health literacy profiling and community engagement to create and implement health reform. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, S.; Cadilhac, D.A.; Lannin, N.A.; Kim, J.; Dalli, L.; Anderson, C.S.; Kilkenny, M.; Shehata, S.; Faux, S.; Dewey, H.; et al. The Australian Stroke Clinical Registry Annual Report 2018; The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health: Heidelberg, Australia, 2019; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, T.F.; Brown, L.; Lam, N.; Wray, F.; Knapp, P.; Forster, A. Information provision for stroke survivors and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD001919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withiel, T.D.; Wong, D.; Ponsford, J.L.; Cadilhac, D.A.; New, P.; Mihaljcic, T.; Stolwyk, R.J. Comparing memory group training and computerized cognitive training for improving memory function following stroke: A phase II randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 51, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Pike, K.; Stolwyk, R.; Allott, K.; Ponsford, J.; McKay, A.; Longley, W.; Bosboom, P.; Hodge, A.; Kinsella, G.; et al. Delivery of neuropsychological interventions for adult and older adult clinical populations: An Australian expert working group clinical guidance paper. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2023, 34, 985–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, T.A.; Worrall, L.E.; Hickson, L.M.; Hoffmann, T.C. Aphasia friendly written health information: Content and design characteristics. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2011, 13, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, T.; Worrall, L.; McKenna, K. The effectiveness of aphasia-friendly principles for printed health education materials for people with aphasia following stroke. Aphasiology 2003, 17, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamborn, E.; Carragher, M.; O’Halloran, R.; Rose, M.L. Optimising Healthcare Communication for People with Aphasia in Hospital: Key Directions for Future Research. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2024, 12, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, M.; Withiel, T.; Klaic, M.; Fisher, C.A.; Simpson, L.; Wong, D. Characterisation of young stroke presentations, pathways of care, and support for ’invisible’ difficulties: A retrospective clinical audit study. Brain. Impair. 2024, 25, IB23059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, S.; Pike, K.; Long, B.; Ma, H.; Bourke, R.; Wright, B.; Wong, D. “I felt like I was not a priority”: A qualitative study of the lived experience of ischaemic stroke patients treated with endovascular clot retrieval and intravenous thrombolysis. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2025. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, A.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Bayley, M.; Kiss, A.; Herrmann, N.; Murray, B.J.; Swartz, R.H. “Good outcome” isn’t good enough: Cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and social restrictions in physically recovered stroke patients. Stroke 2017, 48, 1688–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, B.; Isaacs, M.; Brogan, E.; Shrubsole, K.; Kilkenny, M.F.; Power, E.; Godecke, E.; Cadilhac, D.A.; Copland, D.; Wallace, S.J. An updated systematic review of stroke clinical practice guidelines to inform aphasia management. Int. J. Stroke 2023, 18, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroke Foundation. Working Effectively with People with Lived Experience to Design, Conduct and Promote Stroke Research. 2025. Available online: https://informme.org.au/learning-modules/working-effectively-with-people-with-lived-experience-to-design-conduct-and-promote-stroke-research (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Aphasia Institute. Introduction to Supported Conversation for Adults with Aphasia (SCA™) eLearning Module. 2025. Available online: https://www.aphasia.ca/health-care-providers/education-training/online-options/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).