The Effect of Wearing Elastic Compression Stockings on Leg Edema in Pregnant Women in Late Pregnancy as Determined by Measuring the Deep Venous Velocity and Flow

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects and Study Approval

2.2. Assessment of the Grade of Pitting Grading

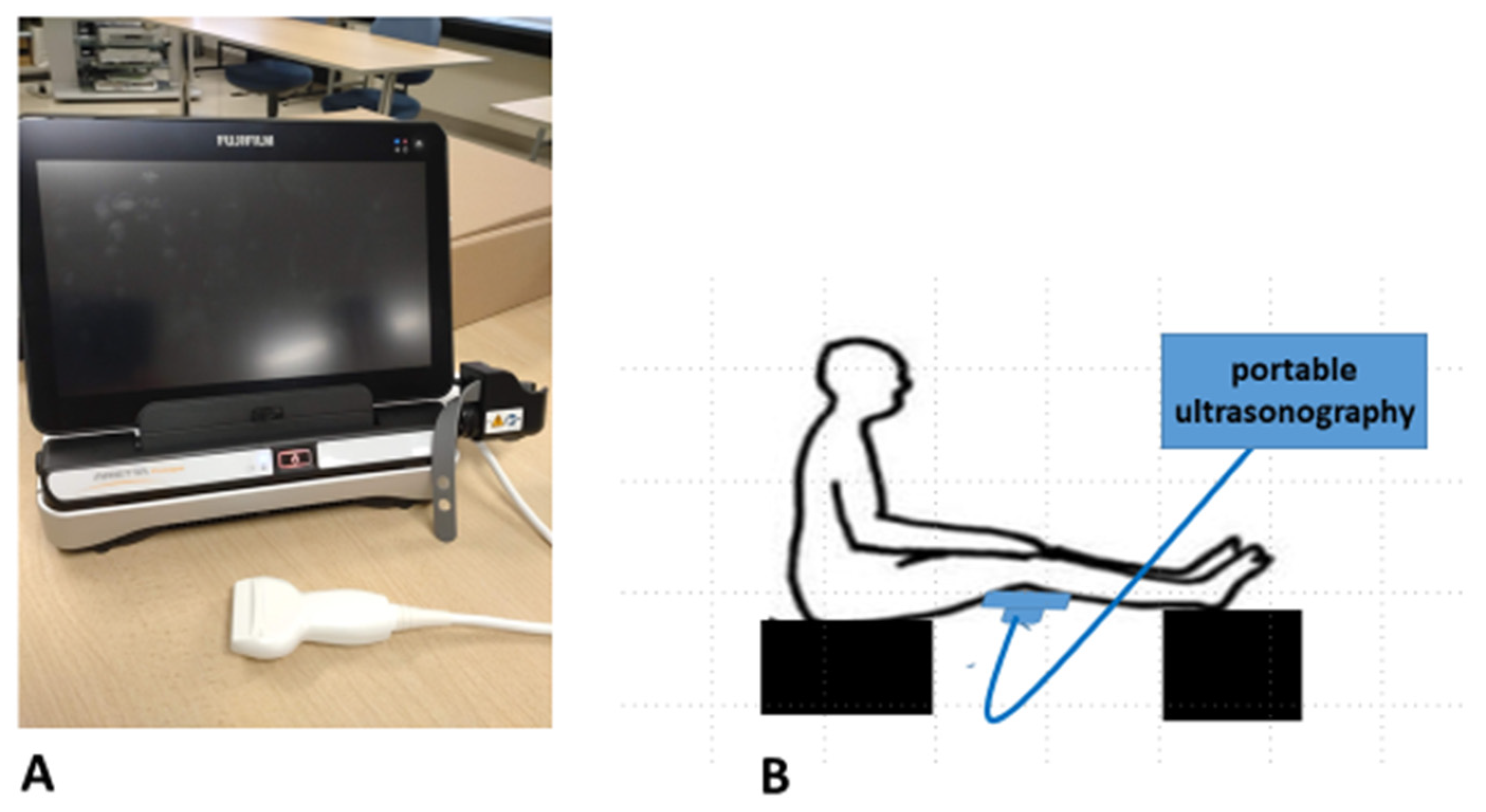

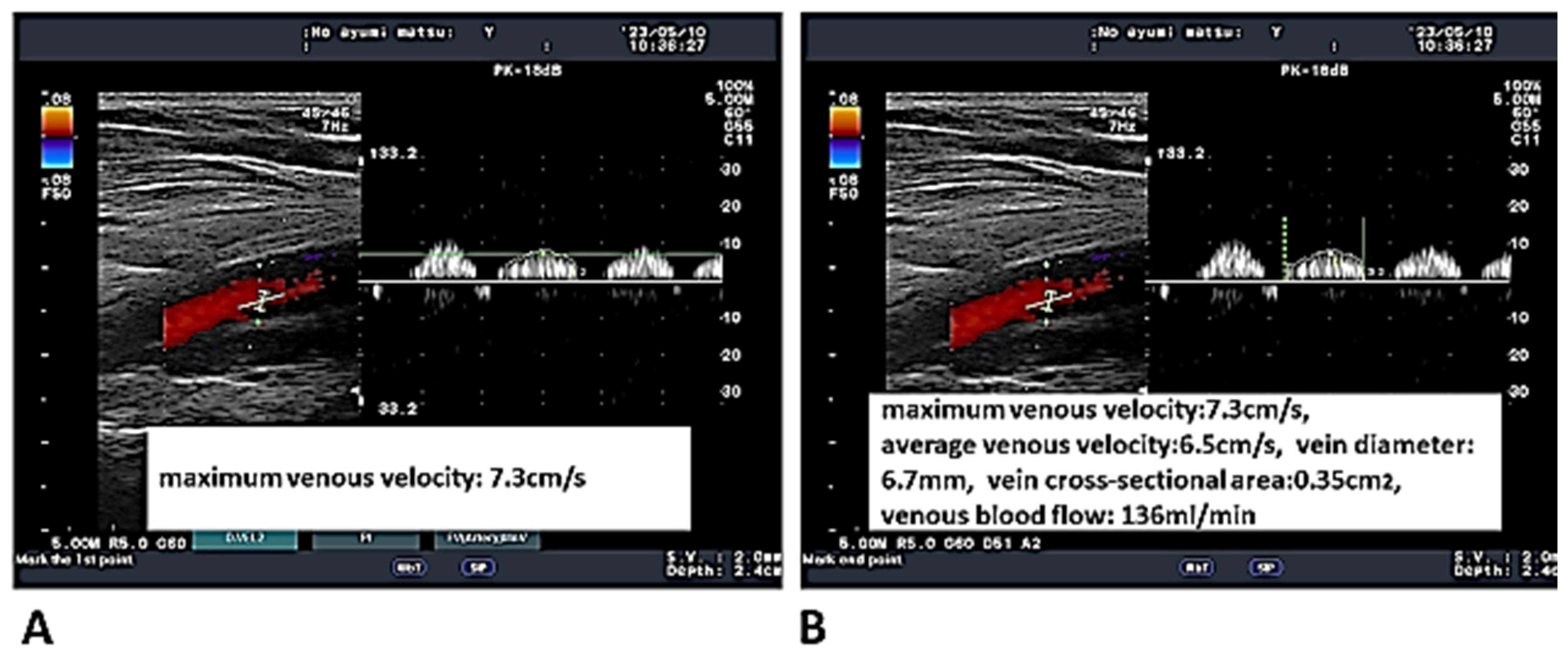

2.3. Measurements of the Deep Venous Velocity and Flow

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Participants (Table 1)

| Controls | Subjects | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 non-pregnant women: 36 legs | 66 pregnant women: 132 legs | ||||

| Age | 29.78 ± 7.98 y | 31.12 ± 4.76 y | 0.2 | ||

| 26 non-edematous | |||||

| and 10 edematous legs | 46 non-edematous legs vs. 44 edematous legs vs. 42 edematous legs | 0.16 | |||

| Age | 30.30 ± 3.87 y | 31.04 ± 6.62 y | 32.05 ± 2.84 y | 0.12 | |

| Primipara | 24 legs | 24 legs | 16 legs | ||

| Multipara | 22 legs | 20 legs | 26 legs | 0.19 | |

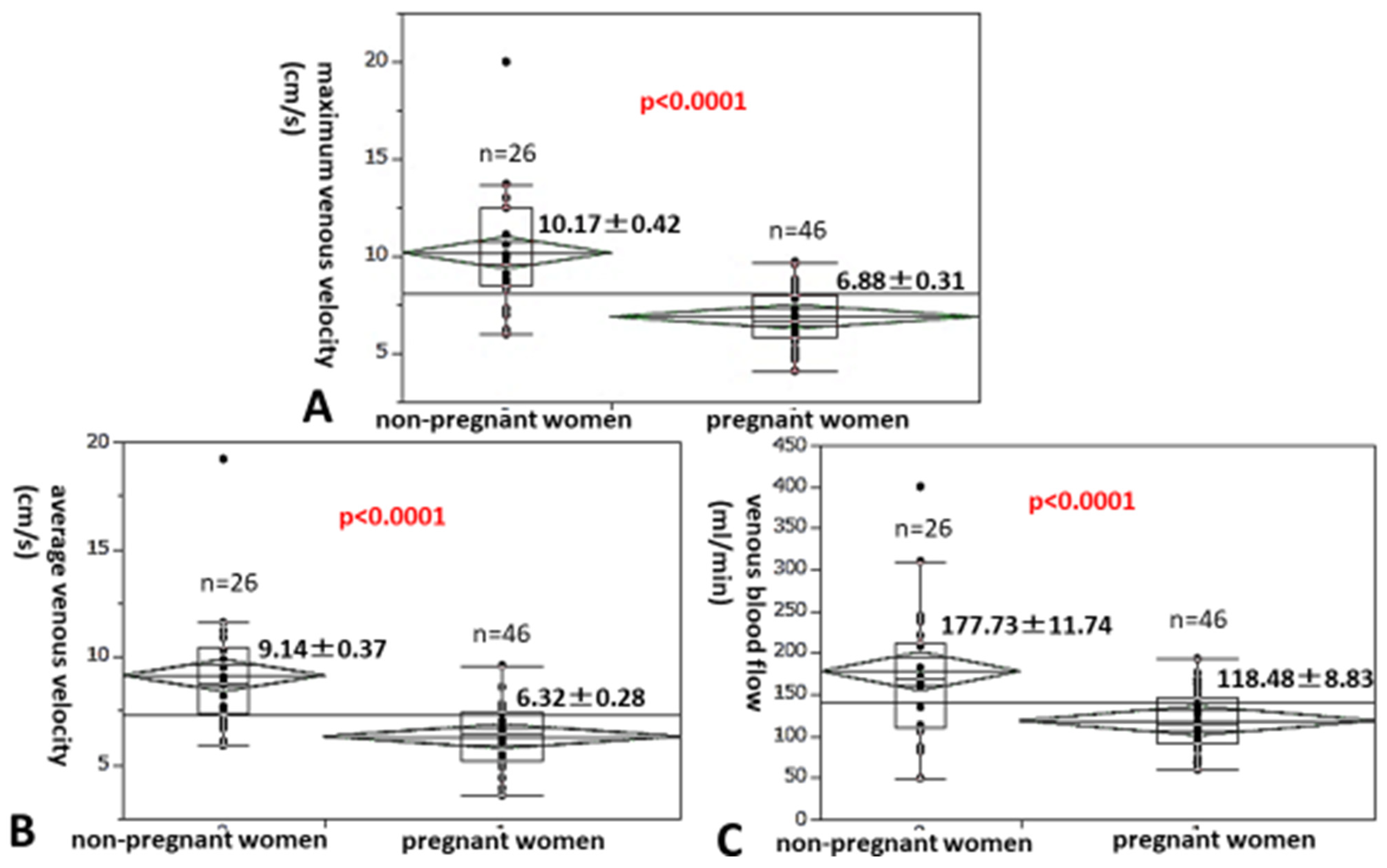

3.2. A Comparison of the Maximum and Average Venous Velocities as Well as the Venous Blood Flow Between Non-Pregnant Women and Pregnant Women in Late Pregnancy

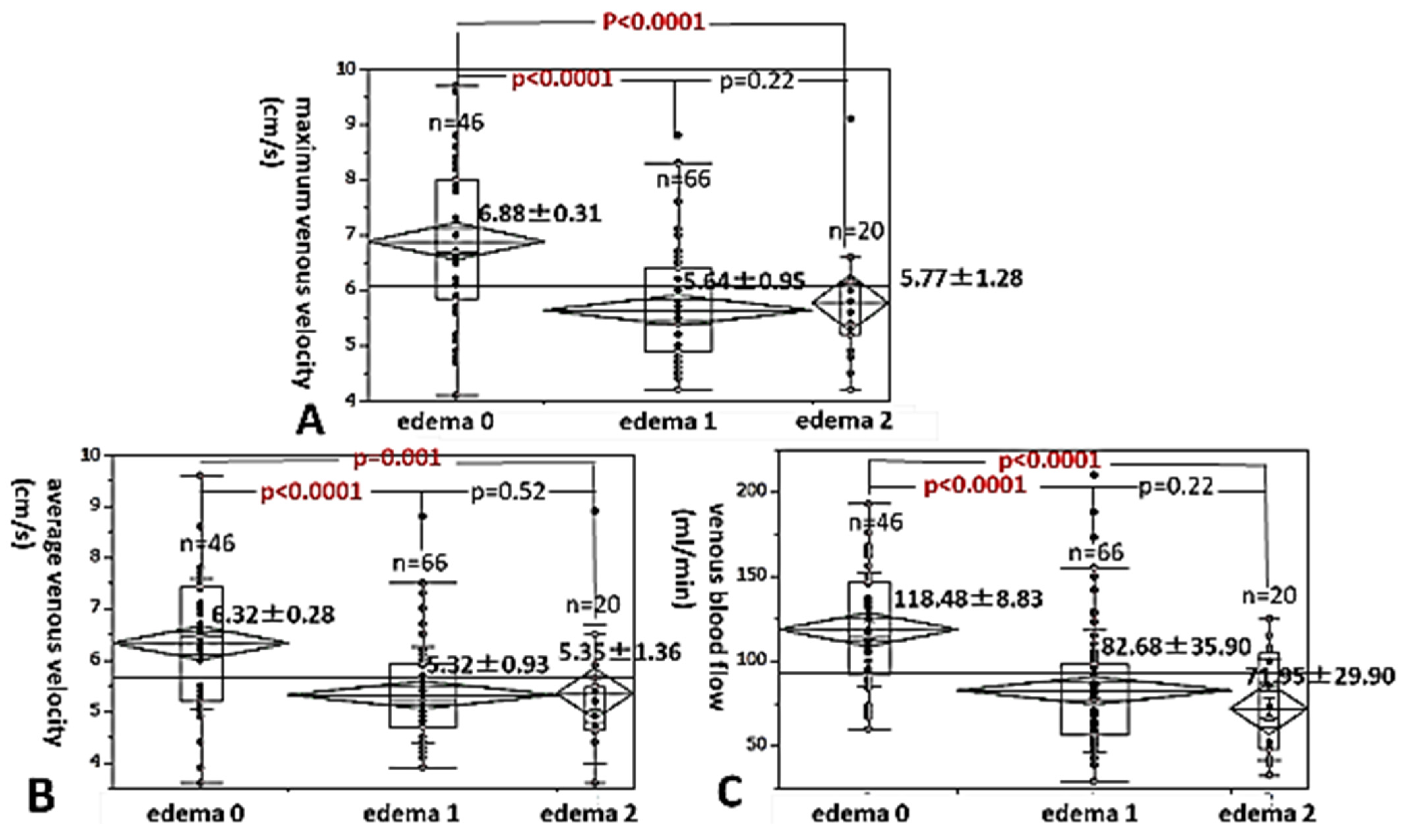

3.3. A Comparison of the Maximum and Average Venous Velocities, and the Venous Blood Flow Among Degrees of Leg Edema in Late Pregnancy

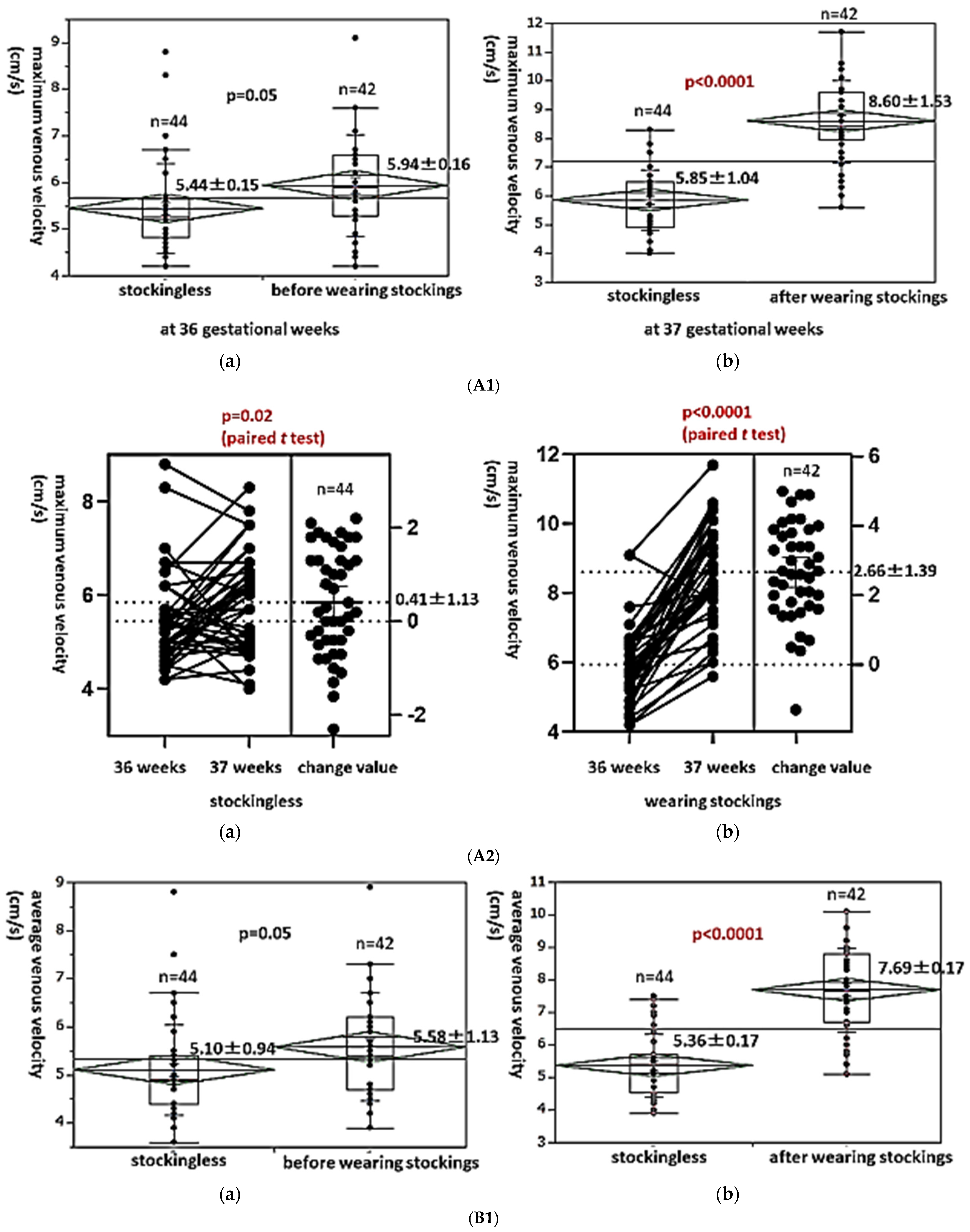

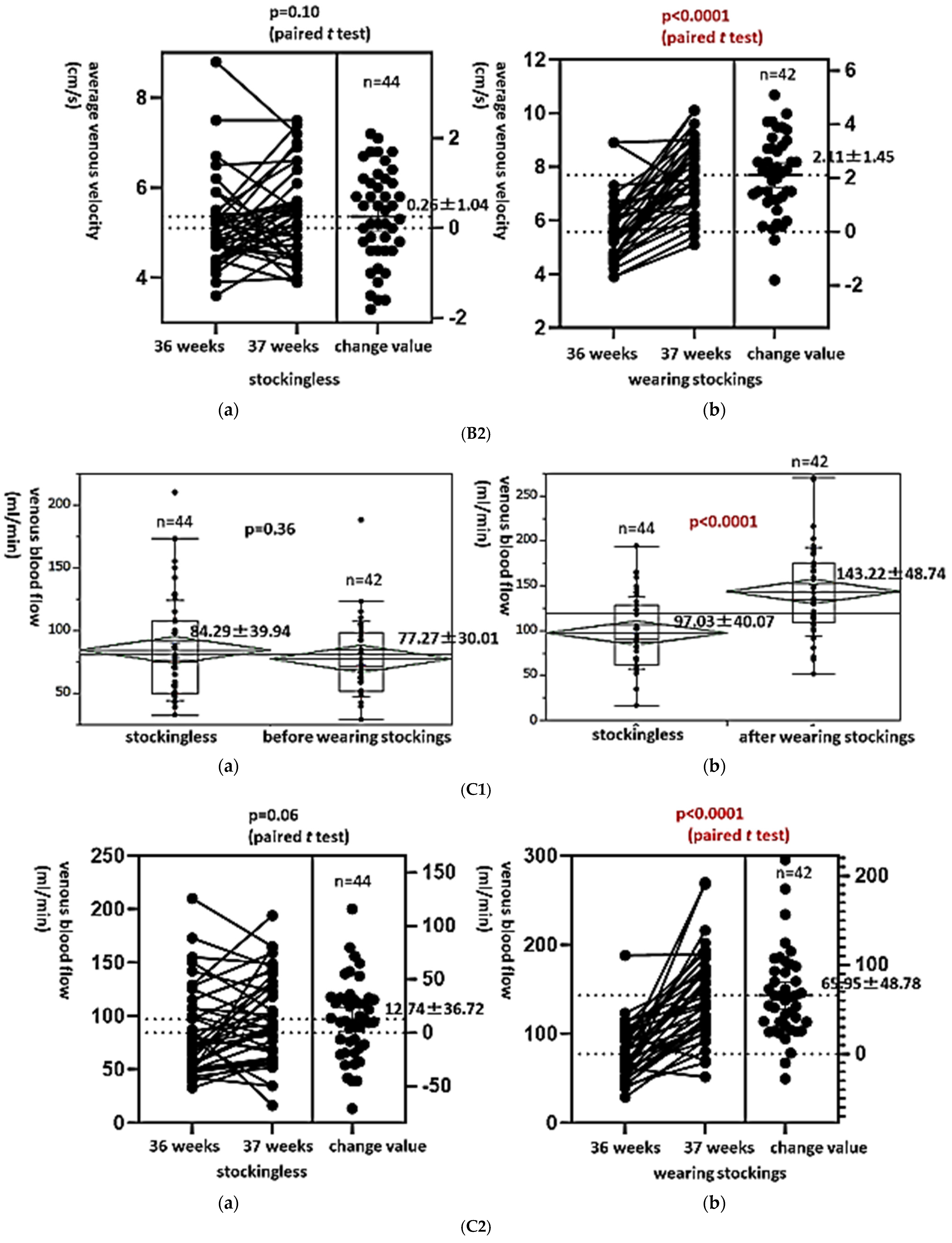

3.4. Level Changes in the Maximum and Average Venous Velocities and the Venous Blood Flow in the Edematous Leg in Late Pregnancy Before and After Wearing Elastic Compression Stockings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cunningham, F.G.; Gant, N.F.; Leveno, K.J.; Larry, C. Williams Obstetrics, 21st ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tranveer, T.; Shahid, S. Frequency of lower extremity edema during third trimester of pregnancy. South Asian J. Med. Sci. 2015, 1, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Trayes, K.P.; Studdiford, J.S. Edema: Diagnosis and management. Am. Fam. Physician 2013, 88, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Swiet, M. Medical Disorders in Obstetric Practice, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 1995; p. 612. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, A.A.; Armstrong, M.A. Peripheral edema. Am. Fam. Physician 1997, 55, 1721–1726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bracero, L.A.; Didomenico, A. Massive vulvar edema complicating preeclampsia: A management dilemma. J. Perinatol. 1991, 11, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Banba, A.; Koshiyama, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Makino, K.; Ikuta, E.; Yanagisawa, N.; Ono, A.; Nakagawa, M.; Seki, K.; Sakamoto, S.I.; et al. Measurement of Skin Thickness Using Ultrasonography to Test the Usefulness of Elastic Compression Stockings for Leg Edema in Pregnant Women. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura-Ogasawara, M.; Ebara, T.; Matsuki, T.; Yamada, Y.; Omori, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kato, S.; Kano, H.; Kurihara, T.; Saitoh, S.; et al. Endometriosis and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss as New Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism during Pregnancy and Post-Partum: The JECS Birth Cohort. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 119, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, K.; Ojima, T.; Urano, T.; Kobayashi, T. The incidence and prognosis of thromboembolism associated with oral contraceptives: Age-dependent difference in Japanese population. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2018, 44, 1766–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devis, P.; Knuttinen, M.G. Deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy: Incidence, pathogenesis and endovascular management. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2017, 7 (Suppl. S3), S309–S319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujovichi, J.L. Hormones and pregnancy: Thromboembolic risks for women. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 126, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichinger, S. D-dimer testing in pregnancy. Semin. Vasc. Med. 2005, 5, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.H.; Tapson, V.F.; Goldberg, S.Z. Thrombosis during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, M.; Koshiyama, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Sato, S.; Sakamoto, S. A quantitative method to measure skin thickness in leg edema in pregnant women using B-scan portable ultrasonography: A comparison between obese and non-obese women. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmgren, J.; Kirkinen, P. Venous circulation in the maternal lower limb: A Doppler study with the Valsalva maneuver. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 8, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, H.; Kirkinen, P.; Mueller, R.; Schnarwyler, B.; Huch, A.; Huch, R. Blood flow velocity waveforms in large maternal and uterine vessels throuout pregnancy and postpartum: A longitudinal study using Duplex sonography. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1988, 95, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.T.; Chahin, A.; Amin, V.D.; Khalaf, A.M.; Elsayes, K.M.; Wagner-Bartak, N.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, S.; Bedi, D.G. Qualitative slow blood flow in lower extremity deep veins on Doppler ultrasound: Qualitative assessment and a preliminary evaluation of correlation with subsequent DVT development in a tertiary care oncology center. J. Ultrasound Med. 2017, 36, 1867–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hanzawa, K.; Sueta, D.; Kojima, S.; Fukuda, M.; Usuku, H.; Kihara, F.; Hosokawa, H.; et al. Risk factors and prevalence of deep vein thrombosis after the 2016 Kumamoto Eartquakes. Circ. J. 2019, 83, 1342–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimunová, M.; Zvonař, M.; Kolářová, K.; Janík, Z.; Mikeska, O.; Musil, R.; Ventruba, P.; Šagat, P. Changes in lower extremity blood flow during advancing phases of pregnancy and the effects of special footwear. J. Vasc. Bras. 2017, 16, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamigboye, A.A.; Hofmeyr, G.J. Interventions for leg edema and varicosities in pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2006, 129, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Koshiyama, M.; Yanagisawa, N. Treatment of leg and foot edema in women. Women’s Health Open J. 2017, 3, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochalek, K.; Pacyga, K.; Curyło, M.; Frydrych–Szymonik, A.; Szygula, Z. Risk factors related to lower limb edema, compression, and physical activity during pregnancy: A retrospective study. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2017, 15, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, C.; Antignani, P.L.; Will, K.; Allaert, F. Acceptance compliance and effects of compression stockings on venous functional symptoms and quality of life of Italian pregnant women. Int. Angiol. 2014, 33, 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Saliba Junior, O.A.; Rollo, H.A.; Saliba, O.; Sobreira, M.L. Positive perception and efficacy of compression stockings for prevention of lower limb edema in pregnant women. J. Vasc. Bras. 2022, 21, e20210101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felty, C.L.; Rooke, T.W. Compression Therapy for Chronic Venous Insufficiency. In Seminars in Vascular Surgery: 2005; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berliner, E.; Ozbilgin, B.; Zarin, D.A. A systematic review of pneumatic compression for treatment of chronic venous insufficiency and venous ulcers. J. Vasc. Surg. 2003, 37, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pana, R.C.; Pana, L.M.; Istratoaie, O.; Duta, L.M.; Gheorman, L.M.; Calborean, V.; Popescu, M.; Voinea, B.; Gheorman, V.V. Incidence of pulmonary and/or systemic thromboembolism in pregnancy. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2016, 42, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Testa, S.; Passamonti, S.M.; Paoletti, O.; Bucciarelli, P.; Ronca, E.; Riccardi, A.; Rigolli, A.; Zimmermann, A.; Martinelli, I. The “Pregnancy Health-care Program” for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2015, 10, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Schneider, K.T.M.; Bung, P.; Fallenstein, F.; Huch, A.; Huch, R. Kreislaufwirkung von Kompressionsstrümpfen in der Spätschwangerschaft. Geburtshilfe Und Frauenheilkd. 1987, 47, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mori, K.; Koshiyama, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Okamoto, N.; Yanagisawa, N.; Banba, A.; Ikuta, E.; Ono, A.; Seki, K.; Nakagawa, M.; et al. The Effect of Wearing Elastic Compression Stockings on Leg Edema in Pregnant Women in Late Pregnancy as Determined by Measuring the Deep Venous Velocity and Flow. Healthcare 2025, 13, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030214

Mori K, Koshiyama M, Watanabe Y, Okamoto N, Yanagisawa N, Banba A, Ikuta E, Ono A, Seki K, Nakagawa M, et al. The Effect of Wearing Elastic Compression Stockings on Leg Edema in Pregnant Women in Late Pregnancy as Determined by Measuring the Deep Venous Velocity and Flow. Healthcare. 2025; 13(3):214. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030214

Chicago/Turabian StyleMori, Kanon, Masafumi Koshiyama, Yumiko Watanabe, Noriko Okamoto, Nami Yanagisawa, Airi Banba, Eri Ikuta, Ayumi Ono, Keiko Seki, Miwa Nakagawa, and et al. 2025. "The Effect of Wearing Elastic Compression Stockings on Leg Edema in Pregnant Women in Late Pregnancy as Determined by Measuring the Deep Venous Velocity and Flow" Healthcare 13, no. 3: 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030214

APA StyleMori, K., Koshiyama, M., Watanabe, Y., Okamoto, N., Yanagisawa, N., Banba, A., Ikuta, E., Ono, A., Seki, K., Nakagawa, M., Sakamoto, S.-i., Hara, Y., & Nakashima, A. (2025). The Effect of Wearing Elastic Compression Stockings on Leg Edema in Pregnant Women in Late Pregnancy as Determined by Measuring the Deep Venous Velocity and Flow. Healthcare, 13(3), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030214