Attachment and Emotional Eating: A Scoping Review Uncovering Relational Roots to Inform Preventive Healthcare

Highlights

- Secure attachment styles serve as a shield against emotional eating, while anxious attachment heightens vulnerability.

- Stress acts as a key moderator, shaping how attachment influences emotional eating.

- Emotion regulation and body awareness bridge the link between attachment and emotional eating.

- Research rarely delves into early attachment representations and child–caregiver bonds.

- Findings remain culturally narrow, with limited diversity in age, gender, and global representation.

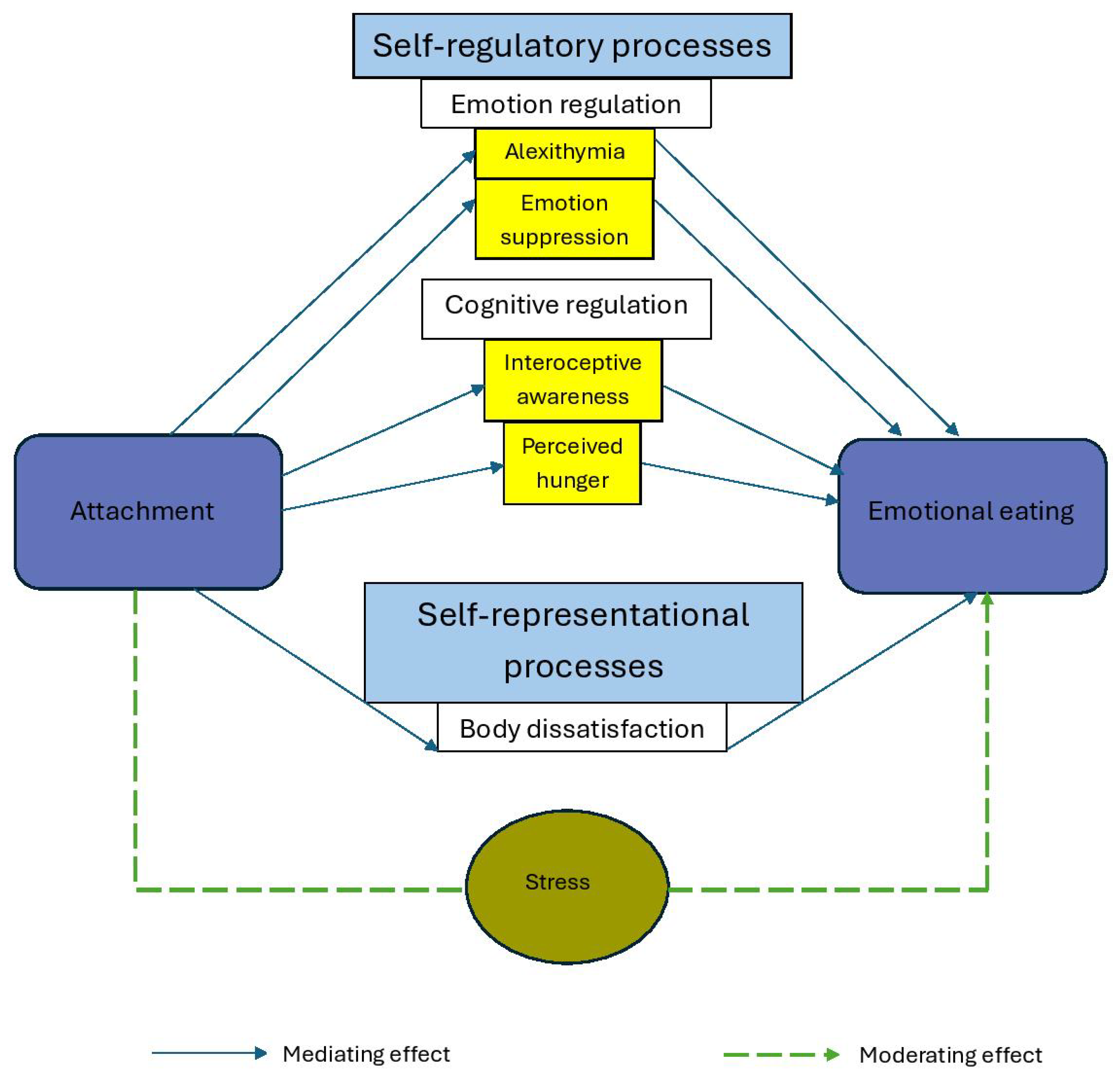

- Attachment insecurity, particularly attachment anxiety, is consistently associated with greater emotional eating, whereas secure attachment is generally protective. This relationship is evident across general attachment styles and, in adults, specific attachment figures (e.g., romantic partners).

- Psychological mechanisms such as emotion regulation difficulties, perceived hunger, body dissatisfaction, and stress moderate or mediate the attachment–emotional eating link, highlighting the complexity and context dependence of this relationship.

- The review calls for research on diverse populations, gender, and pubertal factors, psychological mediators, and caregiver attachment links to emotional eating.

- Integrating attachment- and emotion-focused strategies in preventive healthcare may reduce emotional eating. Considering body dissatisfaction, perceived hunger, stress, and cultural or developmental context can improve the design of behavioral and nutritional programs to prevent emotional eating.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Explore whether attachment, as a style or as a representation, is associated with emotional eating in the general population of adolescents and adults, and if this association exists in different socio-cultural contexts.

- 2.

- Explore the mechanisms that mediate and moderate the relationship between attachment and emotional eating and their relevance to different socio-cultural contexts.

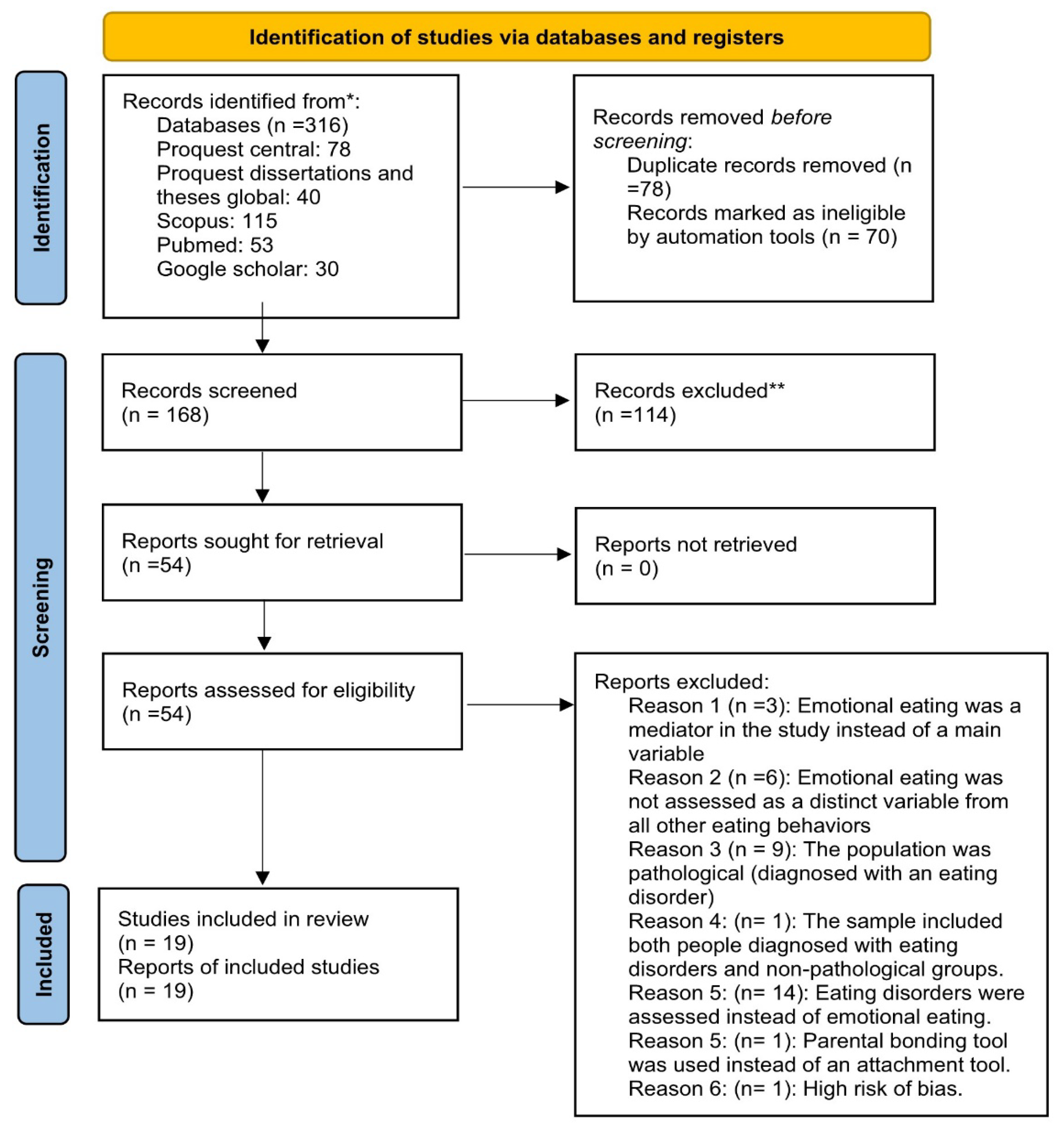

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Screening, Selection, and Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Attachment Security and Emotional Eating

3.3. Attachment Anxiety and Emotional Eating

3.4. Attachment Avoidance and Emotional Eating

3.5. Disorganized Attachment and Emotional Eating

3.6. Mediating Variables

3.6.1. Emotion-Regulatory Processes

3.6.2. Interoceptive Awareness and Perceived Hunger

3.6.3. Body Dissatisfaction

3.7. Moderating Variables

Stress and Coping

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARQ | Adolescent Relationship Questionnaire |

| ECR | Experiences in Close Relationships scale |

| ECR-R | Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Revised |

| EE | Emotional Eating |

| EES | Emotional Eating Scale |

| EES-AF | Angry/Frustrated Eating |

| EES-Anx | Anxious Eating |

| EES-DEP | Depressive Eating |

| EO | Emotional Overeating |

| EU | Emotional Undereating |

| RAAS | The Revised Adult Attachment Scale |

| RQ | Relationship Questionnaire |

| SAAM | State Attachment Anxiety Model |

| S-AQS | The Shortened Version of the Attachment Q-Set |

| SSSP | The Shortened Strange Situation Procedure |

References

- Wansink, B.; Payne, C. Mood self-verification explains the selection and intake frequency of comfort foods. Adv. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, H.S.J.; Soong, R.Y.; Ang, W.H.D.; Ngooi, J.W.; Park, J.; Yong, J.Q.Y.O.; Goh, Y.S.S. The global prevalence of emotional eating in overweight and obese populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychol. 2025, 116, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Strien, T.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; van Leeuwe, J.; Snoeck, H.M. The Stice model of overeating: Tests in clinical and non-clinical samples. Appetite 2005, 45, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultson, H.; Kukk, K.; Akkermann, K. Positive and negative emotional eating have different associations with overeating and binge eating: Construction and validation of the positive-negative emotional eating scale. Appetite 2017, 116, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, P.G.; Boersma, H. Making sense of being fat: A hermeneutic analysis of adults’ explanations for obesity. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2005, 5, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagha, M.; Al-Alam, F.; Saroufine, K.; Elias, L.; Klaimi, M.; Nabbout, G.; Harb, F.; Azar, S.; Nahas, N.; Ghadieh, H.E. Binge eating disorder and metabolic syndrome: Shared mechanisms and clinical implications. Healthcare 2025, 13, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C.; Dingemans, A.; Junghans, A.F.; Boevé, A. Feeling bad or feeling good, does emotion affect your consumption of food? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 92, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herle, M.; Fildes, A.; Steinsbekk, S.; Rijsdijk, F.; Llewellyn, C.H. Emotional over- and under-eating in early childhood are learned not inherited. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffone, F.; Atripaldi, D.; Barone, E.; Marone, L.; Carfagno, M.; Mancini, F.; Saliani, A.M.; Martiadis, V. Exploring the role of guilt in eating disorders: A pilot study. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papandreou, D.; Spanoudaki, M.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. The association of emotional eating with overweight/obesity, depression, anxiety/stress, and dietary patterns: A review of the current clinical evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, W.; Papies, E.K.; Aarts, H. From homeostatic to hedonic theories of eating: Self-regulatory failure in food-rich environments. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godet, A.; Fortier, A.; Bannier, E.; Coquery, N.; Val-Laillet, D. Interactions between emotions and eating behaviors: Main issues, neuroimaging contributions, and innovative preventive or corrective strategies. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 807–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, L.J.; Barnhart, W.R.; Diorio, G.; Gallo, V.; Geliebter, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional questionnaire studies of the relationship between negative and positive emotional eating and body mass index: Valence matters. Appetite 2025, 209, 107966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: Assessed in the Strange Situation and at Home; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Main, M.; Solomon, J. Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention, 1st ed.; Greenberg, M.T., Cicchetti, D., Cummings, E.M., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 121–160. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, B.E.; Waters, E. Attachment Behavior at Home and in the Laboratory: Q-Sort Observations and Strange Situation Classifications of One-Year-Olds. Child Dev. 1990, 61, 1965–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Main, M.; Kaplan, N.; Cassidy, J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1985, 50, 66–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrehumbert, B.; Karmaniola, A.; Sieye, A.; Meister, C.; Miljkovitch, R.; Halfon, O. Les modèles de relations: Développement d’un autoquestionnaire d’attachement pour adultes. Psychiatr. Enfant 1996, 39, 161–206. [Google Scholar]

- Varley, D.; Sherwell, C.S.; Kirby, J.N. Attachment and propensity for reporting compassionate opportunities and behavior in everyday life. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1409537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.L.; Read, S.J. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 644–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R.C.; Waller, N.G.; Brennan, K.A. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, H.S.; Waters, E. The attachment working model’s concept: Among other things, we build script-like representations of secure base experiences. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2006, 8, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillath, O.; Hart, J.; Noftle, E.E.; Stockdale, G.D. Development and validation of a state adult attachment measure. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijers, R.; Miragall, M.; van den Berg, Y.; Konttinen, H.; van Strien, T. Parent–infant attachment insecurity and emotional eating in adolescence: Mediation through emotion suppression and alexithymia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, A.P.; Hart, E.; Chow, C.M. Attachment, rumination, and disordered eating among adolescent girls: The moderating role of stress. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 26, 2271–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taube-Schiff, M.; Van Exan, J.; Tanaka, R.; Wnuk, S.; Hawa, R.; Sockalingam, S. Attachment style and emotional eating in bariatric surgery candidates: The mediating role of difficulties in emotion regulation. Eat. Behav. 2015, 18, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakhour, M.; Haddad, C.; Salameh, P.; Sacre, H.; Hallit, R.; Akel, M.; Kheir, N.; Hallit, S.; Obeid, S. Association between adult attachment styles and disordered eating among a sample of Lebanese adults. Res. Sq. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Southern, M. Understanding the Association Between Attachment, Interoceptive Awareness, and Unhealthy Eating Behaviours. Master’s Thesis, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-García, L.; Rodríguez-Cano, R.; von Soest, T. Prospective associations between loneliness and disordered eating from early adolescence to adulthood. Int. J. Eat Disord. 2022, 55, 1678–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, A.; Dubé, L.; Knäuper, B. Attachment and eating: A meta-analytic review of the relevance of attachment for unhealthy and healthy eating behaviors in the general population. Appetite 2018, 123, 410–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Geary, N.; Asarian, L.; Leeners, B. Best practices for including sex as a variable in appetite research. Appetite 2025, 207, 107840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F.R.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, A.; van Strien, T. The influence of body dissatisfaction on emotional eating in adolescents. Eat. Behav. 2005, 6, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, C.; Stok, F.M.; de Ridder, D.T.D. Emotional eating: Food as a means to regulate mood. In Handbook of Behaviorism; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, B. Why Is English the Language of Science? Slate Magazine. 2015. Available online: https://slate.com/technology/2015/01/english-is-the-language-of-science-u-s-dominance-means-other-scientists-must-learn-foreign-language.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, K.E. Attachment Insecurity and Emotional Eating. Doctoral Dissertation, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Newark, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, C. A Study Investigating the Relationship Between Adult Attachment, Eating Behaviour, Weight, and Emotional Expression in Childhood. Master’s Thesis, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland, 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262536369 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Maras, D. Attachment Style and Obesity: Examination of Eating Behaviours as Mediating Mechanisms in a Community Sample of Ontario Youth; Carleton University: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.E.; Siegel, H.I. Perceived hunger mediates the relationship between attachment anxiety and emotional eating. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, S.E.; Wnuk, S.; Cassin, S.; Jackson, T.; Hawa, R.; Sockalingam, S. Prospective study of attachment as a predictor of binge eating, emotional eating and weight loss two years after bariatric surgery. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.L.; Rowe, A.C.; Robinson, E.; Hardman, C.A. Explaining the relationship between attachment anxiety, eating behaviour and BMI. Appetite 2018, 127, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.L.; Rowe, A.C.; Millings, A. Disorganized attachment predicts body mass index via uncontrolled eating. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 44, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P.; Mackay, E. Psychological determinants of emotional eating: The role of attachment, psychopathological symptom distress, love attitudes and perceived hunger. Curr. Res. Psychol. 2014, 5, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, H.I.; Louka, P. The experience of emotional eating in individuals with insecure attachment style: An interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. Ment. Health 2022, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Hons, C.; Woolley, S. Women’s experiences with emotional eating and related attachment and sociocultural processes. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2011, 38, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnow, B.; Kenardy, J.; Agras, W.S. The emotional eating scale: The development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. Int. J. Eat Disord. 1995, 18, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkard, A.J.; Messick, S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J. Psychosom. Res. 1985, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; Bergers, G.P.A.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int. J. Eat Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on interpersonal regulation. In Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 251–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. The Bowlby-Ainsworth attachment theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 1979, 2, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domic-Siede, M.; Guzmán-González, M.; Sánchez-Corzo, A.; Álvarez, X.; Araya, V.; Espinoza, C.; Zenis, K.; Marín-Medina, J. Emotion regulation unveiled through the categorical lens of attachment. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Colina, A.M. Self-regulation and behavioural risk factors for obesity in youth facing adversity: Emotion regulation difficulties are related to greater reward-based eating and sleep disturbances in youth facing adversity. Obes. Med. 2025, 31, 101832. [Google Scholar]

- Braden, A.; Ahlich, E.; Koball, A.M. Emotional eating and obesity: An update and new insights. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.O.; Narens, L. Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings. In The Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Bower, G., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; Volume 26, pp. 125–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch, H. Psychological aspects of overeating and obesity. Psychosomatics 1964, 5, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, C.; Pereira, A.T.; Maia, B.; Marques, M.; Soares, M.J.; Bos, S.; Macedo, A. Perfectionism and eating behaviour in Portuguese adolescents. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2010, 18, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Duarte, C. Self-criticism, perfectionism and eating disorders: The effect of depression and body dissatisfaction. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2014, 14, 409–420. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran, R.; Mansell, W. Perfectionism and psychopathology: A review of research and treatment. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 879–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, K.J.; Wild, S.; Dillon, K.R.; Shimrock, R. Don’t bring me down. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 35, 936–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Iwanski, A. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H. Universality claim of attachment theory: Children’s socioemotional development across cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11414–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, N. Liens d’attachement: Une autre perspective pour une autre culture. Étude exploratoire sur des enfants libanais. Enfance 2020, 2, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, M.; Patterson, E. Emotion-Focused Therapy for Eating Disorders; Within Health: Miami, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dolhanty, J.; Lafrance, A. Emotion-focused family therapy for eating disorders. In Clinical Handbook of Emotion-Focused Therapy; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 403–423. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, B.; Cooper, G.; Hoffman, K.; Marvin, B. The Circle of Security Intervention: Enhancing Attachment in Early Parent–Child Relationships; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Topham, G.L. The Circle of Security Intervention: Building Early Attachment Security; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, L.; Pezzulo, G. Keep your interoceptive streams under control: An active inference perspective on Anorexia Nervosa. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 20, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzulo, G.; Barca, L.; Friston, K. Active inference and cognitive-emotional interactions in the brain. Behav. Brain Sci. 2015, 38, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrehumbert, B.; Santelices, M.P.; Ibáñez, M.; Alberdi, M.; Ongari, B.; Roskam, I.; Stievenart, M.; Spencer, R.; Rodríguez, A.F.; Borghini, A. Gender and attachment representations in the preschool years: Comparisons between five countries. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2009, 40, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nader, P.; Ghadieh, H.E.; Abbas, N.; Nahas, N. Attachment and Emotional Eating: A Scoping Review Uncovering Relational Roots to Inform Preventive Healthcare. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233170

Nader P, Ghadieh HE, Abbas N, Nahas N. Attachment and Emotional Eating: A Scoping Review Uncovering Relational Roots to Inform Preventive Healthcare. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233170

Chicago/Turabian StyleNader, Pamela, Hilda E. Ghadieh, Nivine Abbas, and Nayla Nahas. 2025. "Attachment and Emotional Eating: A Scoping Review Uncovering Relational Roots to Inform Preventive Healthcare" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233170

APA StyleNader, P., Ghadieh, H. E., Abbas, N., & Nahas, N. (2025). Attachment and Emotional Eating: A Scoping Review Uncovering Relational Roots to Inform Preventive Healthcare. Healthcare, 13(23), 3170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233170