Abstract

Background/Objectives The main aim of the literature review was to determine whether different trigger point therapy techniques are effective in decreasing the intensity, frequency, and duration of tension-type headaches. An additional aim was to assess the impact of trigger point therapy on other physical and psychological variables in tension-type headaches. Methods This literature review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed using the PICO(s) strategy. Searches were carried out in four databases: PubMed, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, and PEDro. Results Of the 9 included studies with 370 participants, 6 studies were randomised controlled trials, 2 were pilot studies, and 1 was a case report. Conclusions Trigger point therapy has reduced the duration, intensity, and frequency of headaches. Dry needling, ischaemic compression, Positional Relaxation Techniques, and massage protocols focused on deactivating trigger points are effective methods of unconventional treatment of tension-type headaches.

1. Introduction

Tension-type headaches (TTHs) are defined as bilateral pressing or tightening types of pain with mild to moderate intensity. The intensity of pain is not increased by physical activity, nor is it associated with vomiting and nausea [1]. TTHs are considered the most common type of primary headaches across all age categories [2]. According to the 2013 Global Burden of Disease Study, the prevalence of TTHs is estimated at 21.75% of the population, regardless of age, and is considered the second most common chronic disease worldwide [3]. This condition is regarded as a significant socio-economic problem, accounting for around 9% of annual sick leave. TTHs are also accompanied by a reduction in the quality of life and have a negative impact on the degree of disability [4]. In many cases, TTHs accompany such disorders as fibromyalgia, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, or hypothyroidism [5]. However, despite the significant impact of tension-type headaches on public health, the aetiology and mechanism of this condition are not fully established. It has been suggested that peripheral factors are associated with episodic tension-type headaches, while central factors are involved in the development of chronic pain [6]. Another important factor involved in tension-type headaches is muscle dysfunction, including myofascial trigger points [7].

Myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) are defined as small, hypersensitive areas within muscle fibres with a palpable lump and tissue thickening. Under pressure, they cause tenderness and pain that is referred to another region, sometimes distant from the MTrPs. Additionally, it is often accompanied by a local twitch response, i.e., a contraction of individual fibres (not the entire muscle) [8]. The causes of trigger points are not entirely known; however, the most likely Integrated Trigger Point Hypothesis (ITPH) states that many factors affect the sarcomeres and motor endplates, making them hyperactive. This, in turn, causes pathological changes at the cellular level, including reduced oxygen supply, involuntarily shortened muscle fibres, abnormal biochemical composition with elevated concentrations of acetylcholine, noradrenaline, and serotonin, and a lower pH [9,10]. These findings could be linked to the peripheral and central sensitisation model which helps in understanding chronic or amplified pain [9,11]. In addition, trigger point pain could project to the head and neck areas, reproducing the pain pattern of tension-type headaches [12].

TTH treatment relies on both conventional and unconventional methods. One of the most commonly used non-conventional methods is manual therapy (MT) [13]. It has been proven that the use of MT in the treatment of TTH can be more effective than usual General Practise care [14]. However, there has been no literature review focused solely on the use of myofascial trigger point therapy in the treatment of TTH so far. Therefore, the main aim of the literature review was to determine whether different trigger point therapy techniques are effective in decreasing the intensity, frequency, and duration of tension-type headaches. An additional aim was to assess the impact of trigger point therapy on other physical and psychological variables in tension-type headaches.

The research questions for this systematic review were:

- Are various trigger points therapy techniques effective in treatment of tension-type headaches?

- How trigger points therapy affect physical and psychological variables in tension-type headaches?

2. Materials and Methods

This literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement [15].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in Table 1 were developed according to the PICO(S) strategy [16].

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria according to the PICO(s) strategy.

2.2. Search Strategy

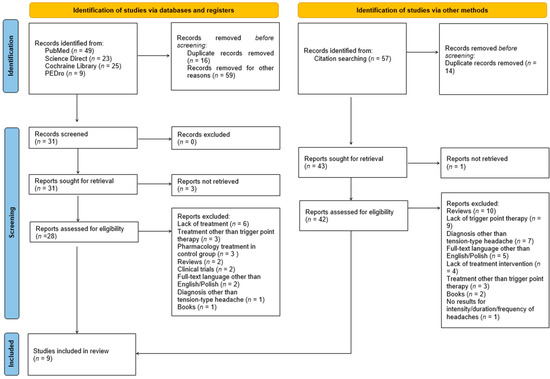

The initial database searches were conducted in May 2021 in four electronic databases: PubMed, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, and PEDro. The databases were selected based on previous systematic reviews [17,18,19,20]. The reference lists of all identified studies were manually examined to identify any articles missed by the electronic literature search. There were no restrictions on years of publication. The following formulas were used to search the databases: PubMed—“trigger point*” AND (“tension-type headache” OR “tension headache” OR “tension type headache”) AND (“physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy”); Cochraine Library -”trigger point*” AND (“tension-type headache” OR “tension headache” OR “tension type headache”) AND (“physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy” OR “therapy”); Science Direct—“trigger points” AND (“tension-type headache” OR “tension headache” OR “tension type headache”); PEDro—“trigger points” AND “tension-type headache”. The review process consisted of two stages. Three independent authors (A.D., M.B., W.W.) initially screened and identified relevant titles and abstracts. Then, full-text versions of articles were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies regarding the inclusion of studies were resolved by the senior researcher (P.G.) [18]. Therefore, a total of 9 studies were included in the final analysis. The article selection procedure is presented in the flow diagram shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

2.3. Data Extraction and Evaluation of the Methodological Quality of Studies

Two authors (W.W., M.B.) independently extracted data from the included articles and compared their findings for accuracy. The extracted date concerned the study design, participants (amount, TTH diagnosis, control group), treatment of TrP (treated muscles, type of TrP, trigger point therapy techniques), outcomes (general outcomes, pain intensity, frequency, duration, other), follow-up, and side effects.

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated by using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale [21] and the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s (CEBM’s) Levels of Evidence Scale [22]. Any disagreements on data extraction or evaluation of the methodological quality of studies were resolved by the third author (A.D.).

3. Results

Of the 9 included studies with 370 participants, 6 studies were randomised controlled trials, 2 were pilot studies, and 1 was a case report. The characteristics of the studies and their methodology can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics and methodology of the included studies.

Pain intensity was the most frequently measured indicator of tension-type headache (nine of the nine studies included in the review). Seven out of the nine included studies [23,25,26,28,29,30,31] assessed the frequency of pain occurrence, and only four studies [25,29,30,31] measured the duration of a single episode of headache. Four studies assessed the quality of life [23,25,29,30]. Three studies assessed the pressure pain threshold (two local PPT [26,30], one local and distal PPT [28]). Two studies reported patients’ medication consumption [24,30]. Single studies assessed the range of cervical motion [26], the number of trigger points [24], the brain metabolite profile [28], and perceived clinical changes [30]. A follow-up was performed in five studies [23,25,27,29,30]. A summary of each study’s outcomes is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the included studies.

The evaluation of the studies using the PEDro scale showed the diversified methodological quality of the included papers. The PEDro scores for the RCT ranged from 1 to 9. The work of Gildir et al. [25] received the highest PEDro score among the included studies (9/10 points—“excellent” quality). According to the PEDro scale, the studies of Kamali et al. [26], Abaschian et al. [23], Berggreen, Wiik, and Lund [24], Mohamadi et al. [28], and Moraska et al. [30] showed “good” quality of the methodology (between 6 and 8 points). The pilot studies of Moraska, Chandler [29], von Stülpnagel et al. [31], and the case study of Mohamadi, Ghanbari, and Rahimi Jaberi [27] were not considered in the PEDro scale analysis. The study of Gildir et al. [25] was also the only included paper rated 1b on the Levels of Evidence scale. The remaining experimental works were ranked as level 2b. The most common reason for a 2b rank was a small sample size and lack of follow-up. Based on the Levels of Evidence Scale, the pilot studies of Moraska, Chandler [29], von Stülpnagel et al. [31], and the case study of Mohamadi, Ghanbari, and Rahimi Jaberi [27] are ranked in place four. Full results of the study’s quality analysis are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Analysis of the methodological quality of included studies according to the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale and the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s (CEBM’s) Levels of Evidence Scale.

4. Discussion

Both clinical and scientific evidence suggests that the treatment of tension-type headaches should be based on pharmacological as well as non-pharmacological methods [32]. The previous research shows the validity of the unconventional, physiotherapeutic treatment of TTH [33,34]. One of the physiotherapy methods with proven effectiveness in TTH treatment is manual therapy, defined as a treatment consisting of a combination of mobilisations of the cervical and thoracic spine, exercises, and postural correction [13]. However, in the above-mentioned literature reviews, the myofascial trigger point therapy was not used to treat TTH or was part of the whole physiotherapy procedure. The knowledge about referred pain from trigger points as well as the involvement of trigger points in the peripheral and central sensitisation mechanisms suggests that the MTrP therapy may be of significant importance in unconventional TTH treatment. Therefore, the main aim of the literature review was to determine whether different trigger point therapy techniques are effective in decreasing of intensity, frequency, and duration of tension-type headaches.

In the studies included in the review, the most frequently used physiotherapeutic method was dry needling. According to The American Physical Therapy Association, DN is “a skilled intervention that uses a thin filiform needle to penetrate the skin and stimulate underlying myofascial trigger points, muscular, and connective tissues for the management of neuromusculoskeletal pain and movement impairments” [35]. The influence of DN on indicators of tension-type headaches was analysed in studies of Abaschian et al. [23], Gildir et al. [25], and Kamali et al. [26]. In the paper of Abaschian et al., the use of dry needling with passive muscle stretching was compared with passive stretching alone in people with episodic tension-type headaches. The inclusion of DN in the ETTH treatment protocol caused a significant improvement in the headache frequency and intensity. Moreover, performing only a passive stretch without inactivation of trigger points caused an increase in headache indicators. The authors of the study recommend the use of DN in the treatment of TTH due to the low costs and short duration of therapy [23]. In the study conducted by Gildir et al., the use of DN in patients with CTTH resulted in a reduction in the intensity, frequency, and duration of the pain episode, and the analgesic effect of DN was maintained after a monthly follow-up [25]. It is worth mentioning that in this study the control group consisted of patients who underwent sham-needling, which is a form of placebo. The lack of improvement in pain indicators in this group may suggest that the use of needle therapy in tension-type headaches may be particularly effective when it is aimed at deactivating trigger points. In the studies of Kamali et al., dry needling was as effective as friction massage. However, DN had a greater effect on increasing the pressure pain threshold of the muscles [26]. Only one study concerning dry needling in the treatment of TTH reported side effects. In the study by Gildir et al., the study participants reported pain and fear during needle application [25].

One of the most commonly used physiotherapeutic techniques to treat trigger points is ischaemic compression [36], which was used in the work of von Stülpnagel et al. [31] and Berggreen, Wiik, and Lund [24]. Ischaemic compression is defined as a manual technique in which the therapist applies pressure directly on the trigger point to reduce the blood supply and decrease the tension within the involved muscle [37,38]. In the Berggreen, Wiik, and Lund paper, ischaemic compression of trigger points reduced the intensity of the morning CTTH but did not affect the intensity of the pain in the evening. However, in this study, medicine consumption decreased significantly in the intervention group and increased in the control group, although not statistically significantly. The number of trigger points also decreased significantly in the intervention group. The authors suggest that due to the potential side effects of pharmacological treatment, myofascial trigger point massage should be considered an effective alternative in a clinical setting [24]. The treatment protocol of von Stülpnagel et al. included also local stretching of the taut band and active or passive stretching of the muscle combined with postisometric relaxation [31]. The results of this study show a reduction in all headache indicators—intensity, frequency, and duration. In both studies, the authors did not report any side effects [24,31].

Another technique for treating TrP in TTH was positional release techniques used in the paper of Mohamadi et al. [28] as well as Mohamadi, Ghanbari, and Rahimi Jaberi [27]. positional release techniques are osteopathic techniques aimed at increasing muscle flexibility by placing it in a shortened position to promote muscle relaxation [39]. Due to its delicate, passive character, PRT has been proposed as a technique for the treatment of chronic, subacute, and acute conditions [36]. These suggestions were confirmed by the studies included in the review. In the work of Mohamadi et al., the use of the positional relaxation technique reduced both the intensity and frequency of tension-type headaches [28]. The results of Mohamadi, Ghanbari, and Rahimi Jaberi’s studies suggested a reduction in the intensity of the patient’s tension-type headache, which lasted for the next 8 weeks until a family conflict occurred [27]. This result may be explained by the fact that psychological stress is one of the suggested factors in the development of trigger points [36].

In addition to using single techniques to treat tension-type headaches, two studies used a 45-min massage protocol focused on reducing the myofascial trigger point activity. In both studies, the use of a standardised massage protocol decreased headache frequency [29,30]. In the study of Moraska and Chandler, the intensity of the headache and duration of a single headache episode also decreased, both in patients with episodic and chronic headaches [29]. However, in the work of Moraska et al. these indicators have not changed in both the intervention, placebo, and waitlists group, and neither did medication use. Additionally, the frequency of headache decreased in both the intervention and placebo groups. The authors suggest that this finding may be explained by the fact that all chronic conditions are responsive to placebo [30]. However, it is worth mentioning that in this study only participants from the intervention group indicated a significant improvement in the perceived clinical change. Also, the pressure pain threshold increased only in the intervention group [30]. These discrepancies in the results of the study by Moraska et al. [30] indicate the need to implement a placebo group in research on pain caused by trigger points.

An additional aim of the literature review was to assess the impact of trigger point therapy on other physical and psychological variables in tension-type headaches. In addition to reducing the intensity, duration, and frequency of headaches, trigger point therapy appears to affect other aspects of pain in patients with tension-type headaches. The study by Mohamadi et al. [28] demonstrated a significant decrease in sensory, affective, and evaluative values, as well as in various aspects of pain measured by the Persian-language version of the McGill Pain Questionnaire. The research also confirmed the increase of the local pressure pain threshold in patients with tension-type headaches after the trigger point therapy [28]. The same result, i.e., an increase in local pain threshold, was achieved in a comparison study of dry needling and friction massage performed by Kamali et. al. [26]. In this study, DN was more effective in increasing the PPT compared to FM. Simultaneously, both methods did not affect the cervical range of motion. Differences were noticed only in extension, which increased in the dry needling group [26]. In opposition to the research of Mohamadi et al., the study results of Berggreen, Wiik, and Lund show no difference in the McGill Pain Questionnaire [24].

It is worth noting that some forms of tension-type headaches may be related to vascular abnormalities, and the therapies described may have a positive effect on treating them by promoting local vasodilation associated with these forms [40,41].

In addition to the influence on physiological variables, the MTrPs therapy may also affect other aspects of the TTH patient’s health. This has been confirmed by Gildir et al. who evaluated health-related quality of life factors by using a Turkish version of the Short Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaire in their study. In the dry-needling intervention group, a significant improvement was observed at the end of the therapy and during a 1-month follow-up in all factors of the Quality of Life test [25]. In contrast to these results, a study conducted by Abaschian et al., who also used the SF-36 questionnaire, obtained different results. Their study showed significant differences only in physical functioning and no significant changes affecting other aspects of quality of life. However, those results may arise from a lack of significant statistical differences between the quality of life in the groups before intervention [23]. The SF-36 questionnaire also showed no improvement in Berggreen, Wiik, and Lund’s research [24]. The increase in quality of life after TrP treatment was confirmed by the use of HDI and HIT-6 questionnaires in the study of Moraska et al. However, in this study, placebo therapy also contributed to the improvement of the quality of life measured with the HIT-6 scale [30]. The HDI questionnaire was also used in Morska and Chandler’s study on massage therapy, and it also showed improvement in the study subjects’ quality of life [29].

The aforementioned authors, who provide plausible evidence of the positive effect of the MTrP therapy on TTH, suggest as an explanation the phenomenon of referred pain, which is a pain felt in an often unexpected region, different from the original site of the painful stimulus [42]. Simons et al. describe referred pain as a repetitive pain from MTrP that does not follow myotomes, dermatomes, or nerve roots. MTrP pain occurs in the so-called maps (patterns) that indicate projection areas from specific myofascial trigger points [43]. Some cervical trigger points project pain into the head region and may be mistaken for headaches of other origins [44,45]. Fernandez-de-las-Penas et al. showed that tension-type headache patients had active myofascial trigger points evoking the same referred pain and sensory characteristics as their habitual headache [46,47]. Researchers have shown that several muscles, i.e., the upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, splenius capitis, or suboccipital muscles, can cause projected pain to the head mimicking a headache, which is simultaneously indicative of the role of active TrP [48,49]. Also, some previous studies have shown a direct relationship between the number of trigger points and tension-type headache indicators [50,51]. Another possible explanation of the positive effect of the TrP therapy on TTH is the phenomenon of central sensitisation (CS), defined as a neurophysiological mechanism that causes increased sensitivity and pain responses [52]. CS is associated with numerous chronic musculoskeletal conditions [53]. Previous research about the trigger point pain mechanisms suggests that MTrPs may play an important role in the sensitisation mechanism phenomenon. The clinical picture of pain may result from hyperalgesic and allodynic responses observed also in cases of TTH, which indicate the role of the peripheral and central mechanisms. Both hyper-excitability of the central nervous system, as well as reduction in the inhibitory mechanisms, are involved in tension-type headaches [50]. As a result of repeated or intense stimulation of the nociceptor present in the periphery, there may be an increase in excitability and the synaptic efficacy of the central nociceptive pathway neurons manifested as hypersensitivity to pain (tactile allodynia) [9,11]. In addition, the studies by Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al. revealed an elevated level of allogeneic substances in active TrP compared to the latent and tender points, which may be the cause for greater afferent stimulation into the nucleus caudalis. This could result in temporary and spatial summation of neuron signals and may lead to central sensitisation in chronic tension-type headaches [54]. It is suggested that central sensitisation in TTH is caused by the peripheral tissues generating prolonged peripheral nociceptive inputs, and it is dynamically influenced by activity and location of these nociceptive inputs [54]. This demonstrates that elimination of trigger points responsible for abnormal peripheral nociceptive stimulation may result in a reduction of synaptic activity of the central nociceptive pathway neurons, thereby reducing headache intensity. However, the results of this review do not provide a clear answer to the question of whether trigger point therapy in patients with TTH could affect central sensitisation. In the study of Kamali et al. [26], Mohamadi et al. [28], and Moraska et al. [30], the use of trigger point therapy resulted in an increase in the local pressure pain threshold. PPT is considered an adequate parameter in the research into central sensitisation [52]. In previous studies, injection of an anaesthetic into the trigger points of trapezius muscle resulted in a reduction in the peripheral pressure pain threshold in patients with neck pain after whiplash trauma [55]. Therefore, the results of the aforementioned studies may suggest that trigger point therapy may contribute to pain relief in TTH patients through the CS mechanism. In the Mohamadi et al. [28] studies, only local pressure pain threshold increased after trigger point therapy, while the distal PPT values did not change. In this study, also the brain metabolite profile was included in the assessment of central sensitisation. MRI examination showed no significant changes in any variables of the metabolite profile in the group with Positional Release Techniques treatment, which may suggest that this type of therapy did not affect the central nervous system. Thus, due to inconclusive results, the effect of trigger point therapy on central sensitisation in patients with tension-type headaches requires further research.

Results of most included studies have shown that trigger point therapy is effective in reducing pain indices in patients with tension-type headaches. The impact of TrP therapy on the improvement of the quality of life of patients with TTH is inconclusive. Treatment of trigger points increases the local pressure pain threshold. However, the lack of influence of TrP therapy on the distal PPT and brain metabolite profiles does not provide conclusive evidence that the central sensitisation mechanism is involved in the treatment of trigger points in patients with tension-type headaches. Nevertheless, the results of the PEDro assessment and the Levels of Evidence scale indicate the need to develop more refined test protocols, taking into account, e.g., blinded studies and larger study groups, to avoid discrepancies in the results of future research. Also, the inclusion of the group with placebo treatment is needed to not overestimate the positive effect of the trigger point therapy in chronic tension-type headaches.

5. Conclusions

- Trigger point therapy has reduced the duration, intensity, and frequency of headaches.

- Dry needling, ischaemic compression, positional relaxation techniques, and massage protocols focused on deactivating trigger points are effective methods of unconventional treatment of tension-type headaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.D., M.B., W.W., G.Z., J.S. and P.G.; methodology, A.D.; data curation, A.D., M.B. and W.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., M.B. and W.W.; writing—review and editing, A.D., G.Z., J.S. and P.G.; visualisation, A.D.; supervision, J.S. and P.G.; project administration, A.D.; funding acquisition, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anderson, R.E.; Seniscal, C. A Comparison of Selected Osteopathic Treatment and Relaxation for Tension-Type Headaches. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2006, 46, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stovner, L.; Hagen, K.; Jensen, R.; Katsarava, Z.; Lipton, R.; Scher, A.; Steiner, T.; Zwart, J.-A. The Global Burden of Headache: A Documentation of Headache Prevalence and Disability Worldwide. Cephalalgia 2007, 27, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 301 Acute and Chronic Diseases and Injuries in 188 Countries, 1990–2013: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 743–800. [CrossRef]

- Stovner, L.J.; Andrée, C. Impact of Headache in Europe: A Review for the Eurolight Project. J. Headache Pain 2008, 9, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, S.; Ricci, S.; Carolei, A. Tension-Type Headache and Systemic Medical Disorders. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2011, 15, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loder, E.; Rizzoli, P. Tension-Type Headache. BMJ 2008, 336, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, T.P.; Heldarskard, G.F.; Kolding, L.T.; Hvedstrup, J.; Schytz, H.W. Myofascial Trigger Points in Migraine and Tension-Type Headache. J. Headache Pain 2018, 19, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, D.G.; Travell, J.G.; Simons, L.S. Travell & Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: Upper Half of Body; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-683-08363-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bron, C.; Dommerholt, J.D. Etiology of Myofascial Trigger Points. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012, 16, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.P.; Gilliams, E.A. Uncovering the Biochemical Milieu of Myofascial Trigger Points Using in Vivo Microdialysis: An Application of Muscle Pain Concepts to Myofascial Pain Syndrome. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2008, 12, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C.J. Central Sensitization: Implications for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pain. Pain 2011, 152, S2–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Ge, H.-Y.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; González-Iglesias, J.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Referred Pain Areas of Active Myofascial Trigger Points in Head, Neck, and Shoulder Muscles, in Chronic Tension Type Headache. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2010, 14, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victoria Espí-López, G.; Arnal-Gómez, A.; Arbós-Berenguer, T.; González, Á.A.L.; Vicente-Herrero, T. Effectiveness of Physical Therapy in Patients with Tension-Type Headache: Literature Review. J. Jpn. Phys. Ther. Assoc. 2014, 17, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castien, R.F.; van der Windt, D.A.W.M.; Grooten, A.; Dekker, J. Effectiveness of Manual Therapy for Chronic Tension-Type Headache: A Pragmatic, Randomised, Clinical Trial. Cephalalgia 2011, 31, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.d.C.; Pimenta, C.A.d.M.; Nobre, M.R.C. The PICO Strategy for the Research Question Construction and Evidence Search. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakandala, P.; Nanayakkara, I.; Wadugodapitiya, S.; Gawarammana, I. The Efficacy of Physiotherapy Interventions in the Treatment of Adhesive Capsulitis: A Systematic Review. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2021, 34, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk-Zielińska, B.; Ginszt, M. A Meta-Analysis of the Global Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M.R.; Van der Wees, P.J.; Pinheiro, M.B. Using Research to Guide Practice: The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk, A.; Wójcicki, M. Global Prevalence of Sleep Bruxism and Awake Bruxism in Pediatric and Adult Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morton, N.A. The PEDro Scale Is a Valid Measure of the Methodological Quality of Clinical Trials: A Demographic Study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine—Levels of Evidence. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/Oxford-Centre-Evidence-Based-Medicine-Levelsevidence-March-2009/ (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Abaschian, F.; Mansoursohani, S.; Togha, M.; Yassin, M.; Abadi, L. The Investigation of the Effects of Deep Dry Needling into Trigger Points of Temporalis, Sternocleidomastoid and Upper Trapezius on Females with Episodic Tension Type Headache. Res. Bull. Med. Sci. 2020, 25, e6. [Google Scholar]

- Berggreen, S.; Wiik, E.; Lund, H. Treatment of Myofascial Trigger Points in Female Patients with Chronic Tension-Type Headache—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv. Physiother. 2012, 14, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gildir, S.; Tüzün, E.H.; Eroğlu, G.; Eker, L. A Randomized Trial of Trigger Point Dry Needling versus Sham Needling for Chronic Tension-Type Headache. Medicine 2019, 98, e14520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, F.; Mohamadi, M.; Fakheri, L.; Mohammadnejad, F. Dry Needling versus Friction Massage to Treat Tension Type Headache: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2019, 23, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadi, M.; Ghanbari, A.; Rahimi Jaberi, A. Tension—Type—Headache Treated by Positional Release Therapy: A Case Report. Man. Ther. 2012, 17, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadi, M.; Rojhani-Shirazi, Z.; Assadsangabi, R.; Rahimi-Jaberi, A. Can the Positional Release Technique Affect Central Sensitization in Patients With Chronic Tension-Type Headache? A Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraska, A.; Chandler, C. Changes in Clinical Parameters in Patients with Tension-Type Headache Following Massage Therapy: A Pilot Study. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2008, 16, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraska, A.F.; Stenerson, L.; Butryn, N.; Krutsch, J.P.; Schmiege, S.J.; Mann, J.D. Myofascial Trigger Point-Focused Head and Neck Massage for Recurrent Tension-Type Headache: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. J. Pain 2015, 31, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Stülpnagel, C.; Reilich, P.; Straube, A.; Schäfer, J.; Blaschek, A.; Lee, S.-H.; Müller-Felber, W.; Henschel, V.; Mansmann, U.; Heinen, F. Myofascial Trigger Points in Children with Tension-Type Headache: A New Diagnostic and Therapeutic Option. J. Child Neurol. 2009, 24, 406–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitag, F. Managing and Treating Tension-Type Headache. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 97, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano López, C.; Mesa Jiménez, J.; de la Hoz Aizpurúa, J.L.; Pareja Grande, J.; Fernández de las Peñas, C. Efficacy of Manual Therapy in the Treatment of Tension-Type Headache. A Systematic Review from 2000 to 2013. Neurología 2016, 31, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Cuadrado, M.L. Physical Therapy for Headaches. Cephalalgia 2016, 36, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Physical Therapy Association. Physical Therapists & the Performance of Dry Needling: An Educational Resource Paper; American Physical Therapy Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tough, E.A.; White, A.R.; Richards, S.; Campbell, J. Variability of Criteria Used to Diagnose Myofascial Trigger Point Pain Syndrome--Evidence from a Review of the Literature. Clin. J. Pain 2007, 23, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemmell, H.; Miller, P.; Nordstrom, H. Immediate Effect of Ischaemic Compression and Trigger Point Pressure Release on Neck Pain and Upper Trapezius Trigger Points: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Clin. Chiropr. 2008, 11, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.-R.; Tsai, L.-C.; Cheng, K.-F.; Chung, K.-C.; Hong, C.-Z. Immediate Effects of Various Physical Therapeutic Modalities on Cervical Myofascial Pain and Trigger-Point Sensitivity. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, S. Strain-Counterstrain Phenomenon in Skeletal Muscle and Appropriate Therapeutic Intervention. Assoc. Health Phys. Educ. Recreat. 1990, 3, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, K.; Tagliatti, E.; Gagliani, M.C.; Frascio, M.; Zarcone, D.; Raposio, E. Ultrastructural Imaging Reveals Vascular Remodeling in Migraine Patients. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2022, 157, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposio, E.; Raposio, G.; Del Duchetto, D.; Tagliatti, E.; Cortese, K. Morphologic Vascular Anomalies Detected during Migraine Surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2022, 75, 4069–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Svensson, P. Referred Muscle Pain: Basic and Clinical Findings. Clin. J. Pain 2001, 17, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travell, J.G.; Simons, D.G. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-683-08366-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Simons, D.G.; Pareja, J.A. Myofascial Trigger Points and Sensitization: An Updated Pain Model for Tension-Type Headache. Cephalalgia 2007, 27, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Hansen, P.T.; Svensson, P.; Jensen, T.S.; Graven-Nielsen, T.; Bach, F.W. Patterns of Experimentally Induced Pain in Pericranial Muscles. Cephalalgia 2006, 26, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Fernández-Mayoralas, D.M.; Ortega-Santiago, R.; Ambite-Quesada, S.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Pareja, J.A. Referred Pain from Myofascial Trigger Points in Head and Neck-Shoulder Muscles Reproduces Head Pain Features in Children with Chronic Tension Type Headache. J. Headache Pain 2011, 12, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Gerwin, R.D.; Pareja, J.A. Trigger Points in the Suboccipital Muscles and Forward Head Posture in Tension-Type Headache. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2006, 46, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C. Myofascial Head Pain. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2015, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Blanco, C.; de-la-Llave-Rincón, A.I.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C. Muscle Trigger Point Therapy in Tension-Type Headache. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2012, 12, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, J.-H.; Choi, H.-C.; Lee, S.-M.; Jun, A.-Y. Differences in Cervical Musculoskeletal Impairment between Episodic and Chronic Tension-Type Headache. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerwin, R.D.; Dommerholt, J.; Shah, J.P. An Expansion of Simons’ Integrated Hypothesis of Trigger Point Formation. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2004, 8, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Morlion, B.; Perrot, S.; Dahan, A.; Dickenson, A.; Kress, H.G.; Wells, C.; Bouhassira, D.; Drewes, A.M. Assessment and Manifestation of Central Sensitisation across Different Chronic Pain Conditions. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griensven, H.; Schmid, A.; Trendafilova, T.; Low, M. Central Sensitization in Musculoskeletal Pain: Lost in Translation? J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020, 50, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Gerwin, R.D.; Pareja, J.A. Myofascial Trigger Points and Their Relationship to Headache Clinical Parameters in Chronic Tension-Type Headache. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2006, 46, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrom, N.; Freeman, M. Central Sensitization Is Modulated Following Trigger Point Anesthetization in Patients with Chronic Pain from Whiplash Trauma. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study. Pain Med. 2017, 19, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).