Abstract

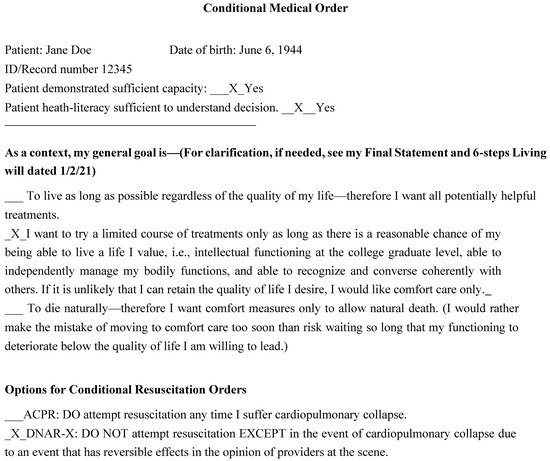

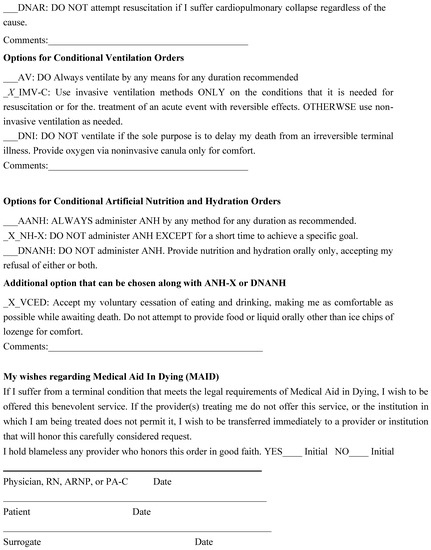

Palliative care discussions offer a unique opportunity for helping patients choose end-of-life (EOL) treatments. These are among the most difficult decisions in later life, and protecting patients’ ability to make these choices is one of healthcare’s strongest ethical mandates. Yet, traditional approaches to advance care planning (ACP) have only been moderately successful in helping patients make decisions that lead to treatments concordant with their values. In particular, neglect of attention to the emotions that occur during consideration of the end of one’s life contributes to patients’ difficulty with engaging in the process and following through on decisions. To improve ACP outcomes, providers can address the patient’s emotional experiences, and can use motivational interviewing as a way attend to elicit them and incorporate them into care planning. Applying personalizing emotion-attuned protocols like Conditional Medical Orders (CMO) also promotes this end.

1. Introduction

Palliative care is offered to patients with serve infirmities that may or not be terminal. There is general agreement that: “The goal of palliative care is to relieve the suffering of patients and their families by the comprehensive assessment and treatment of physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms experienced by patients” [1]. This often involves helping patients find comfort by being able to plan their present and future care by creating advance care plans (ACP). This planning requires good communication among providers, patients, and their families, and ideally through shared decision-making. Effective communication is so critical that the Palliative Care Implementation Project stipulated “Patients’ experience of feeling heard and understood” as its first measurement criteria [2]. One key to good communication is sensitivity to the emotions that the contemplation of illness and death invariably evoke. Unlike the brief contacts in many instances of specialty care, patents tend to have more protracted contact with palliative care providers which increases the possibility of meaningful connection. Unfortunately, this sensitivity is elusive if, as often the case, the connection between cognition and emotion is overlooked.

Descartes’ declaration “I think therefore I am” fueled the Enlightenment’s obsession with cognition, which has persisted until now. But had Descartes known about resent landmark research, he would have expressed a doubly conditional phenomenon: “I feel, therefore I think, therefore I am” [3]. Neuroscience research has demonstrated that all processing in the brain involves emotion as much as or more than rationality. For instance, neurotensin instantly triggers a good/bad reaction in the amygdala to all sensory input [4]. This explains the classic finding that an evaluative dimension is the largest contributor to the meaning of most words in many languages [5]. It also accounts for the automaticity through which individuals begin an action before awareness of the intention to do so [6]. Studies like these highlight the need to consider both cognition and affect in all efforts to understand and manage human behavior [7]. They also demonstrate that: “behavior is the result of the interaction between what we believe and what we feel. If we want to change behavior, it is necessary to change the underlying beliefs and feelings related to that behavior” [8].

These mental processes apply equally throughout life, including planning around death. Yet, in many efforts to help patients with advance care planning, the only discussion involves logical constructs: “clinicians tend to focus on diagnosis, therapy, and cure [so] the imminence of death is often not openly and timely acknowledged in patients with advancing chronic illness” [9]. In the process, clinicians generally neglect the wide range of emotions that many patients experience when they contemplate serious illness and death. These include, but are not limited to, feelings of anger, fear, regret, guilt, loneliness and/or emptiness due to a lack of meaning [10]. Not all the feelings are negative: there may even be relief for those seeking to end the ravages of a terminal illness.

Ignoring emotions like these can seriously undermine the effectiveness of the most well-intended ACP efforts [11]. Without consonant attention to the emotional experiences about the process and content, patients are less likely to complete the needed steps. If something “feels” wrong or unpleasant, even if all the facts line up, they or their families may refuse to participate, may make unrealistic demands, or may acquiesce to the provider’s advice initially only to later do something else.

In order to minimize the risk of these unwelcome emotional outcomes, we suggest ways for providers to manage their own and their patients’ emotions during shared decision-making. We also recommend use of more patient-friendly materials to facilitate the process.

2. Why Providers’ Emotions Matter

Through a process of limbic regulation and the activity of mirror neurons, also known as “mood contagion”, humans and many other animals, covertly experience reactions that are sensed by other creatures, including pain and sadness [12,13]. The resulting social sensitivity can be regarded as a “sixth sense” to others’ feelings. Throughout the animal world, being able to quickly know when another individual is a threat or an opportunity aids survival. Without your verbalizing it, you may have noticed that your pet often becomes more attentive when you are sick or unhappy and flees when it senses your anger. This is an example of how the pet’s limbic system picks up messages from yours. Although they may not be aware of it, providers’ emotions have a similar impact on their patients, who readily sense anxiety, respectful interest, indifference, or disdain. In addition, providers’ emotions color the selection, timing, and manner in which they present alternatives.

Because emotions and healthcare decisions are inextricably intertwined, it is important to attend to the emotional tone of the way both providers and patients participate in discussions [11]. Providers who are ambivalent about an option may present it in an untimely manner or not at all, and those who disapprove of an option are apt to convey their feelings through nonverbal cues and verbal qualification of their messages, such as “this is probably not a good idea, but I have to mention this option…” [14]. Patients who feel that they are discounted or not well understood are unlikely to attend to presentations even if the information they are given is accurate and detailed.

4. Discussion

There may be some hesitation about efforts to address patients’ feelings about intervention rather than more efficiently focusing only on the facts. It definitely can be a more lengthy and complicated process. The World Health Organization acknowledged that “integrative care [is] more time-consuming and challenging than the current practice, [citing} human resource capacity as a barrier” [22]. However, facts alone do not drive patients’ behavior; emotions are often at often at least as powerful, if not more so. If time is spent making recommendations that patients will ignore, that time will be wasted, and the patients’ well-being will be compromised if they or their healthcare provider does not follow through later by readdressing the issue. Fortunately, counterbalancing the cost of more effective shared decision making is the fact that patients who participate in these discussions are more likely to choose less costly treatments [23,24]. For example, one study found that medical expenditures 6 and 3 months before death were significantly lower for patients who were able to discuss options such as palliative care with their providers [25]. Even more important is the likelihood that these discussions will lead to care that is more concordant with patients’ goals and values. There is great moral value in discussions that move patient care from a mechanistic style in which patients are “salvageable” to an organismic approach that recognizes patients’ unique perspectives [26].

When physician and nurse time is very tight, the providers can communicate basic diagnostic and prognostic information to social workers, chaplains, and other well-trained facilitators who can conduct the vital shared-decision-making sessions. These discussions can take place at the bedside, in a clinic or office, or remotely via phone or internet. As a caution, these discussions should be less focused on changing patients’ feelings than help them articulate and understand the likely outcome of acting on their emotions, particularly when the latter conflict with medical realities. Addressing patients’ emotions puts providers at the risk of compassionately sharing their distress, but this a worthwhile price to pay for the opportunity to more meaningfully connect with patients.

The relevance of advance care plans to critical care decisions is always a concern. It has been suggested that ACPs should disease-centered [27]. That would be ideal but it is impractical if, as recommended, planning takes place well in advance of the time they are needed because it is often impossible to anticipate precisely when that need will arise. The CMO comes closest to meeting this criteria by stipulating the conditions under which interventions will be accepted contingent on their effects in the trajectory of any illness. CMOs can be personalized when the details are known.

As a final consideration, once it is understood that emotions profoundly influence what patients learn from providers and how they act on the information they are given, it becomes ethically necessary to address patients’ emotions during shared decision-making. Failing to do so puts patients at greater risk of making poor decisions or failing to follow through on wise choices and puts providers at risk of offering substandard care.

5. Conclusions

Palliative care discussions are an optimal time for ACP. It is easy for providers to ascribe the sparce use of ACP to patients’ lack of motivation and understanding because many people do wish to avoid thinking about illness and dying. Yet, another key factor is providers’ reluctance to discuss death, which many consider a failure rather than an inevitability, and providers’ preference to deal with facts rather than with emotions. Because providers are trained to focus on the science of medicine, it is understandable that many are not equally attentive to the process of emotionally sensitive treatment planning. Attending adequately to emotions requires providers to become aware of and manage their own feelings, because these often profoundly influence patients’ motivation to meaningfully engage in the process. In addition to careful attention to emotions, use of motivational interviewing techniques and choice of personalized and patient-friendly materials like the CMO can help ACP reach its vast potential to improve end-of-life care.

Author Contributions

Authors contributed equally to this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rome, R.B.; Luminais, H.H.; Bourgeois, D.A.; Blais, C.M. The role of palliative care at the end of life. Ochsner J. 2011, 11, 348–352. [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. Implementation Guide Evaluating Patient and Caregiver Voices. Available online: https://aahpm.org/uploads/AAHPM22_PRO-PM_IMPLEMENTATION_GUIDE.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Miceli, C. “I Think Therefore I Am”: Descartes on the Foundation of Knowledge. 1000-Word Philosophy: An introductory Anthology. 2022. Available online: https://1000wordphilosophy.com/2018/11/26/descartes-i-think-therefore-i-am/ (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Li, H.; Namburi, P.; Olson, J.M.; Borio, M.; Lemieux, M.E.; Beyeler, A.; Calhoon, G.G.; Hitora-Imamura, N.; Coley, A.A.; Libster, A.; et al. Neurotensin orchestrates valence in the amygdala. Nature 2022, 609, 586–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, G.E.; Suci, G.J.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh, J.A.; Chen, M.; Burrows, L. Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and steeotype activation on action. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, V.T.; Hagoort, P.; Casasanto, D. Affective primacy vs. cognitive primacy: Dissolving the debate. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, C. Changing behavior using motivational interviewing techniques. J Roy. Soc. Med. 2004, 97 (Suppl. 44), 43. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, B.; Allan, S.; Bakan, M.; Barnestein-Fonseca, P.; Berger, M.; Boughey, M.; Christen, A.; De Simone, G.G.; Egloff, M.; Ellershaw, J.; et al. Live well, die well—An international cohort study on experiences, concerns and preferences of patients in the last phase of ife: The research protocol of the iLIVE study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Emotions and Coping as You Near the End of Live. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/end-of-life-care/nearingtheend-of-life/emotions.html/references (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Zhang, I.Y.; Liao, J.M. Incorporating emotions into clinical decision-making solutions. Heathcare 2021, 9, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsade, S. “The Ripple Effect: Emotional Contagion and Its Influence on Group Behavior”. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 644–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamendella, J.T. The limbic system in human communication. Stud. Neurolingjistics 1977, 3, 157–222. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, A.; Mohan, D.; Alexander, S.C.; Mescher, C.; Barnato, A.E. the language of end-of-life decision making: A simulation study. J. Pal. Med. 2015, 18, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topoll, A.B.; Arnold, R.; Stowers, K.H. Teaching Communication Skills in Real Time. Fast Facts and Concepts #438. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. Available online: https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/teaching-communication-skills-in-real-time/ (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Transtheoretical therapy: Words a more integrative model of change. Psychother. Res. Ther. 1982, 19, 276–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing, 3rd ed.; Helping People Change: Guilford, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, M.T.; Archibald, M.M.; Abagtsheer, R.C.; Kitson, A.L. Factors influencing communication about frailty in primary care: A scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, T.; Larsen, E.; Schnall, R. Unraveling the meaning of patient engagement: A concept analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, R.B.; Thielke, S. Conditional permission to resuscitate: A middle ground for resuscitation. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, R.B.; Birchfield, G.; Little, T.E.; Wetstone, S.; McDermott, J. Use of conditional medical orders to minimize moral, ethical, and legal risk in critical care. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2021, 41, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) Implementation and Pilot Programme: Findings from the ‘Ready’ Phase; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A.A.; Zhang, B.; Ray, A.; Mack, J.W.; Trice, E.; Balboni, T.; Mitchell, S.L.; Jackson, V.A.; Block, S.D.; Maciejewski, P.K.; et al. Association between end-of-life discussions, patientmental health, medical care near death, and caregier bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2009, 300, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Weeks, J.C.; Wright, A.A.; Block, S.D.; Prigerson, H.G. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictions and outcom of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakin, J.R.; Koritsanszky, L.A.; Cunningham, R.; Maloney, F.L.; Neal, B.J.; Paladino, J.; Palmor, M.C.; Vogeli, C.; Ferris, T.G.; Block, S.D.; et al. A systematic intervention to improve serious illness communicztion in primary care: Effect on expenses at the end of life. Healthcare 2020, 8, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, S.S.; Khalsa, S.G.; McBroom, K.; White, D.; Meeker, M.A. The meaning of confort measures only and order sets for hospital-based palliative care providers. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Heath Well-Being 2022, 17, 2015058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, J.F.L.; Asendorf, T.; Simon, A.; Bleckmann, A.; Truemper, L.; Wulf, G.; Overbeck, T.R. “SpezPat”-common advance directives versus disease-centered advance directives; a randomized controlled pilot stuy on the impact on pysicians’ understanding of non-small cell lung cancer patients’ end-of-life decisions. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).