Abstract

The integration of large language models (LLMs) and fuzzy metrics offers new possibilities for improving automated grading in programming education. While LLMs enable efficient generation and semantic evaluation of programming assignments, traditional crisp grading schemes fail to adequately capture partial correctness and uncertainty. This paper proposes a grading framework in which LLMs assess student solutions according to predefined criteria and output fuzzy grades represented by trapezoidal membership functions. Defuzzification is performed using the centroid method, after which fuzzy distance measures and fuzzy C-means clustering are applied to correct grades based on cluster centroids corresponding to linguistic performance levels (poor, good, excellent). The approach is evaluated on several years of real course data from an introductory programming course with approximately 800 students per year called “Programski jezici i strukture podataka” in the first year of studies of multiple study programs at the Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Serbia. Experimental results show that direct fuzzy grading tends to be overly strict compared to human grading, while fuzzy metric correction significantly reduces grading deviation and improves alignment with human assessment, particularly for higher-performing students. Combining LLM-based semantic analysis with fuzzy metrics yields a more nuanced, interpretable, and adaptable grading process, with potential applicability across a wide range of educational assessment scenarios.

MSC:

03E72; 68T05; 97P80; 62H30

1. Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of computer science education, programming assignments serve as a cornerstone for assessing students’ technical proficiency, problem-solving skills, and creativity. However, the assessment of these assignments places significant demands on the instructor’s time and other resources [1], posing significant challenges for educators, particularly in larger classrooms. Traditional manual grading is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to inconsistencies due to subjective interpretations of code quality. In addition to the feedback that AI tools can provide, several studies have shown that one of the functionalities pursued is the automatic grading of students [2]. While automated grading tools have alleviated some of these burdens, they often rely on rigid rule-based systems that prioritize syntactic correctness over nuanced aspects such as code readability, efficiency, or algorithmic elegance. This unvarying approach fails to capture the complexity of human judgment, leaving gaps in feedback that are critical for student growth.

The objective of this paper is to design and evaluate a grading framework that integrates a large language model (LLM) with fuzzy metrics to achieve nuanced, transparent and scalable assessment of programming assignments. This paper addresses the gap between these two approaches by integrating LLM code analysis with a fuzzy grading metric. LLMs, such as GPT-4, have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in understanding and generating human-like text, including code. As mentioned in [3], in LLMs, code and reasoning reinforce each other, since code is highly structured and has strong logic, guiding reasoning in training and inference. These models can parse programming syntax, infer logical intent, and even detect subtle errors or stylistic flaws. Meanwhile, fuzzy metrics can be used as a robust mechanism to quantify subjective criteria like “clean code” or “efficient logic,” which defy binary evaluation. Fuzzy logic has been widely adopted in educational assessment to model partial correctness and linguistic evaluation, overcoming limitations of crisp grading schemes [4,5,6,7].

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- A fuzzy grading model for programming assignments, where each grading criterion is represented by trapezoidal membership functions corresponding to linguistic evaluation levels;

- An LLM evaluation pipeline, in which students’ solutions are assessed according to predefined criteria and given fuzzy grades rather than crisp scores as an output;

- A fuzzy metric-based correction mechanism, employing fuzzy C-means clustering and inverse fuzzy distance weighting to adjust defuzzified scores and improve alignment with human grading;

- An empirical evaluation on real course data, sampled from several years of a large introductory programming course, demonstrating the behavior and limitations of crisp, fuzzy and corrected fuzzy grading;

The motivation for this integration lies in addressing the limitations of existing automated systems. Rule-based graders lack flexibility, while pure machine-learning approaches often operate as “black boxes,” offering little transparency into scoring rationale. By contrast, the proposed system combines the explainability of fuzzy logic’s rule-based architecture with the contextual intelligence of LLMs. Furthermore, it accommodates diverse evaluation criteria, from functional correctness to pedagogical goals like encouraging experimentation or adherence to best practices.

1.1. Field Overview

An overview of the field is displayed in [8], where it is shown that most studies are performed on the academic level of undergraduate students (99 out of 138 in total). Most popular subject domains were Language Learning (17%), Computer Science (16%) and Management (14%), followed closely by Engineering (12%) and Science (10%). AI usage in education is divided into five different categories: Assessment/Evaluation, Predicting, AI Assistant, Intelligent Tutoring System and Managing Student Learning. Assessment/Evaluation is further divided into categories: Automatic Assessment, Generating Tests, Feedback, Review Online Activities and Evaluate Educational Resources. This paper is focusing on Automatic Assessment. In the research performed in [9], multiple courses were graded by AI and by teachers simultaneously. ChatGPT (GPT-5.1) was used as an AI grader, without any additional fine-tuning, so-called zero-shot training. There were differences between grading, where AI had a tendency to give scores that would form a normal distribution, while teachers mostly gave non-passing grades. Agreement on the individual question was low, so there were a lot of situations where AI gave a high score, while the teacher gave a low score and vice versa. AI did the grading multiple times to compare the scoring consistency, where the average scoring and percentage agreements were roughly the same, even though single answers were graded differently between multiple AI grading runs. AI prompts are recommended to be as small as possible, so longer answers were graded worse. Even though there are differences and flaws, the final conclusion is that AI grading could hardly be distinguished from human grading. On the other hand, AI was considered not mature enough to be used for grading at the time. In [10], AI-powered tools were provided to K-12 teachers as a help for grading. It was observed what kind of misconceptions, myths and fears were present, which were influencing the adoption of the AI grader. It gave further depth to teachers on how AI works while complementing teachers’ work. Given both synthetic and real grading data, open-ended biology questions were graded by an AI using an analytic rubric. It was shown that, in order for the AI grader to be adopted by the teachers, they had to have some insights on how it is working to develop trust to use it. To sum up, current research trends in LLMs for automatic scoring are increasingly focusing on the interplay between sophisticated general language understanding and the specific needs in educational applications [11]. Thus, there has been a noticeable increase in research on LLM-powered automated essay scoring (AES) and automated short answer grading (ASAG) in the recent literature [12].

Regarding the combination of LLMs and fuzzy logic, there are emerging references, mostly recent preprints, but early research on this topic could be found in [13]. Here, fuzzy logic is used for model evaluation, but not in direct use by LLM for grading.

1.2. Chapters Overview

The introductory chapter outlines the challenges in traditional and automated grading, the potential of LLMs and fuzzy logic as complementary tools, and the overarching vision of the proposed framework. Subsequent chapters will delve into technical implementation, case studies, and validation against human grading benchmarks. Section 2 describes the existing grading process and introduces the proposed fuzzy and LLM methodologies. Section 3 presents experimental results and comparisons with human grading. Section 4 discusses the observed benefits and limitations of the approach and Section 5 outlines directions for future research. Ultimately, this research seeks to advance educational technology by creating a grading system that is not only efficient but also pedagogically aligned, transforming assessment into a dynamic tool for learning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Current Grading Process

The current state of the grading is that it is performed manually, with some minimal automation to help the grader in the process. The grader is most often a teaching assistant on the course. Students listening to the subjects are divided into groups that could contain at most 32 students. Since every group has its own term when it’s in the computer laboratory and terms rarely overlap, every group receives a different assignment. There are three assignments during the semester, with different levels of difficulty, where the assignments become harder as the semester is going. Teaching assistant that is teaching the group of students is responsible for giving the suggestion of the exam assignment, while taking into consideration guidance provided by the head teaching assistant. Every teaching assistant needs to submit their assignments to the head teaching assistant in order for them to be reviewed. The responsibility of the head teaching assistant is to provide feedback and align the assignments between different teaching assistants/groups, in order to obtain approximately the same level of difficulty for all of the groups. Once the final draft is approved by the head teaching assistant, the assignment could be used in an exam.

Students are given assignments, and their solutions are being picked up from the laboratory as an archive of file systems of all computers in the laboratory. There are some helping tools that can extract student solutions in the form of source files, but using them by a grader is not mandatory. After the preparation step, the grader starts evaluating student solutions one by one. Evaluation includes the following few steps:

- Compilation of the solution and making an executable file;

- Running some static analysis checks, checking for memory leaks;

- Testing the output of the program with some given test input values;

- Manually going through an assignment and checking if the solution contains all of the requested elements, with proper use of programming constructs and library functions of the programming language.

Some simple automation of the evaluation steps is achieved using shell scripting to invoke a compiler (gcc) and do checks with static analysis (cppcheck), memory correctness (valgrind) and testing the output (combination of expect and diff utilities). Graders are still required to go through the solution manually and do the pragmatic analysis of the solution. For every type of assignment, there are categories that are being graded. Both their meaning and maximum number of points are defined by the head teacher assistant. The final grade for the assignment represents a sum of the points for every given category.

2.2. Introducing Fuzzification in the Grading Process

To make the grading process fuzzy, the linguistic variables are introduced as follows:

- Poor, for hardly matching the grading criteria or none.

- Good, for partial fulfillment, but there is a missing part.

- Excellent, for performing everything asked.

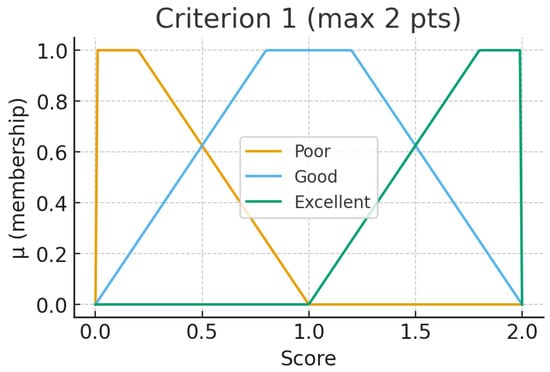

Such linguistic variables are converted into fuzzy sets. For every criterion in Table 1, there are three trapezoidal fuzzy sets that match the linguistic variables affiliation.

Table 1.

Example of the criteria for grading by categories (max. 20 points).

Table 2.

Fuzzy set per criterion.

Figure 1.

Criterion 1 fuzzy set.

After grading using fuzzy criteria, defuzzification is performed using the following formula:

In the numerator, the value of the membership function is multiplied by the centroid value of each trapezoidal function of each linguistic variable. In the denominator, only the membership function value is summed for each of the linguistic variables. This will give a concrete student’s score value as a final result of defuzzification.

2.3. Calculating Fuzzy Distance and Clustering Method

The fuzzy distance measures used in this work are grounded in the theory of fuzzy metric spaces originally introduced by Kramosil and Michálek, further formalized by George and Veeramani [14,15]. These frameworks extend classical metric concepts by allowing uncertainty and graded proximity between elements, making them particularly suitable for modeling imprecision in educational assessment. A broader overview of distance concepts, including fuzzy and generalized distances, can be found in [16].

The distance between two trapezoidal fuzzy sets and using the Euclidean distance is calculated as

Instead of metric (2) fuzzy S-metric defined in [17] will be used as follows:

where will be defined as an absolute difference in two trapezoidal fuzzy sets and . The parameter t has an arbitrary value, greater than 0. By choosing a larger value for t, the closer the trapezoidal fuzzy sets are, the greater the fuzzy S-metric result. That way, in algorithms, aside from standard metrics and fuzzy metrics like the distance between objects, their aggregations are also considered (see [18]), for example,

Fuzzy C-means (FCM) [19] is used as a soft-clustering algorithm. Classical K-means is rigid regarding the membership to a cluster, so this is a less restraining variant, allowing for one data point to belong in multiple clusters with different levels of membership. The steps in the fuzzy C-means algorithm are as follows:

- Initialization, where the number of clusters is given and the fuzzy membership matrix is initialized using random values;

- Cluster centers calculation, where centroids of every cluster are calculated using weighted average of data points, and weights are membership values;

- Update membership matrix: belonging to certain clusters means it is updated, taking into account the distance from the data point and cluster center;

- Recalculate cluster centers: obtain new cluster centers from the updated membership matrix;

- Convergence check: repeat the previous two steps until no significant change occurs or maximum number of iterations is reached.

As input for FCM, fuzzy grades are converted using the centroid method

where a, b, c and d denote the parameters of the trapezoidal membership function. In order to do a self-correcting method of grading, the fuzzy distance and C-means approach are being combined. By clustering data, cluster centers are formed, which are used to determine the average student belonging to a certain group. Let k contain an element that belongs to this fuzzy set,

where G is a fuzzy trapezoidal function for every category. For individual student’s grade (marked with ), calculate the fuzzy distance between every element of and take the closest one to determine the category in which it falls,

Correct the fuzzy grade using fuzzy reverse distance as a weight factor (the closer it is, the stronger the influence),

where p is an exponent used to further tune results, grouping values closer to the cluster’s centers. Notice that if D is a fuzzy metric, is also a fuzzy metric if , which follows from the properties of continuous t-norms and their induced orderings (see [18,20]).

2.4. Usage of LLMs for Grading

In this paper, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, LLM version GPT-5.1, was used. With Chain of Thought enabled, the prompter was in the position to see the thinking process of the LLM. As addressed in [11], it is characterized as a sequence of intermediary reasoning steps expressed in natural language, culminating in the final output. At the moment of writing, the best commercially available GPT model, which promises a smarter, more widely useful model with deeper reasoning [21].

2.5. Calculation and Visualization of Results

To visualize and calculate additional fuzzy grades, Python version 3.10.12 was used. Package numpy version 2.2.6 is used for data arrays and precise calculations. Fuzzy C-means calculation was performed using the scikit-fuzzy package, as well as trapezoidal representation of fuzzy grades. For visualization of Fuzzy C-Means results and trapezoidal functions that were made from the centroids of the clusters, the matplotlib version 3.10.7 package was used.

3. Results

3.1. Crisp Results

As a first experiment, a randomly chosen group of students performed the same assignment. Their work was processed by an LLM (in this case ChatGPT), with the instruction to grade the assignments using crisp criteria defined in Table 1. The assignments were then graded solely by the machine.

The LLM response was a detailed explanation of the points awarded for each criterion. The report was always concluded with the addition of points given for the criteria, yielding the final grade. This result was later used for comparison between human grading. The crisp grading workflow is visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Crisp grading workflow.

Table 3 displays human grades in the first column and crisp LLM in the second. In the third column, there is a calculation of how different the LLM crisp grading is compared to the human grading, expressed in percentages.

Table 3.

Comparison of human and crisp grading using LLM.

3.2. Results Using Fuzzy Grading

Table 4 shows the human grades in the first column, the fuzzy LLM grades in the second and the defuzzified values in the third. In the fourth column, there is a calculation of how different the LLM fuzzy grading is compared to the human grading, expressed in percentages.

Table 4.

Comparison of human and fuzzy grading using LLM.

3.3. Fuzzy Grading Correction

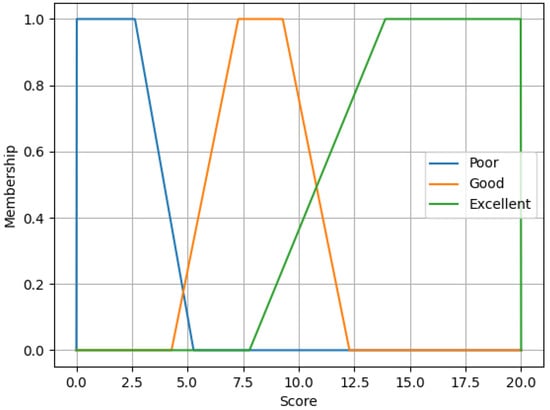

Since it is imprecise by definition, there is a possibility of correcting the fuzzy grading. First, FCM is used to determine centroid values in the clusters. The algorithm is run with parameters to create three clusters: Poor, Good and Excellent. Input values are calculated as centroids for certain fuzzy grades using Equation (5). Clusters are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

FCM cluster centers for provided fuzzy grading values.

Centroids can be unwrapped in trapezoid membership functions. These trapezoids are limited to a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 20 points; therefore, Poor and Excellent are rectangular trapezoids as displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Trapezoid functions derived from the FCM centroids.

Then, with the given centroid trapezoids, calculate the fuzzy distance for every grade. Using the fuzzy reverse distance as a weight factor and centroid for every linguistic variable, correct the grade.

One of the advantages of using fuzzy distance (either S-metric or T-metric) is the existence of the parameter t, where the fuzzy nature of the distance is defined. Regarding the chosen value of t, it is able to obtain more expected results.

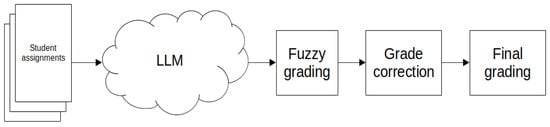

The final workflow that includes fuzzy grading by the LLM and then grading correction is displayed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Fuzzy corrected grading workflow.

In Table 5, along the human grading column, there are three more columns for different values of parameter p introduced in Equation (8). Since the values have a greater converging step up to , there is no need to display results for greater values of p. In the last column, there is a calculation of how different the LLM fuzzy grading is compared to the human grading, expressed in percentages. During the calculations for Table 5, different values of t were used, but the value 100 was chosen because it was giving satisfying results.

Table 5.

Comparison of human and corrected fuzzy LLM grading with different weight factor p.

4. Discussion

As expected, the provided results may vary. While consistency between running is pretty much achieved (small differences in grading the same assignment twice), as it was noticed in [22], some assignments were graded too harshly, especially with fuzzy grading criteria. Despite the apparent strengths of LLMs, they are not specifically designed for AES, nor is it clear how reliable they may be if employed for such purposes [23]. Similar is showing for programming assignments. When comparing the results from Table 3, deviations from the human grading are going up to 50%. Apart from that, deviations were going in both sides; sometimes LLM was more favorable than human grading. By converting grading criteria into fuzzy values and letting LLM grade with such criteria, asking back for a fuzzy value first, and then performing a defuzzification into a crisp value, two things are clearly visible: grading is much more strict, even too much and there are not any cases where LLM gives more points than a human. If we take human grading as fair, this is really unfavorable for students. By using the grading correction where FCM is used to determine the cluster center and centroids of the membership functions and inverse fuzzy distance from every category (Poor, Good, Excellent), certain corrections could be achieved in the right direction.

Taking a look at the cluster center values in Figure 3, since the centers are in smaller interval than min–max points from 0 to 20, scaling had to be performed, using the formula.

In Table 5 there are results for different values of p. The bigger the p was, the more fair the grades were becoming for the best students. There are some cases of harshly graded assignments, where the LLM simply could not determine the real grade; in the case of fuzzy grading, it was too strict. Such cases are becoming worse by increasing the p, because they are getting closer to the center of the “Poor” cluster. Median values of different grading methods are displayed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Median of the grading difference percentage for different methods of grading.

There are a few facts, as follows, that should be taken into consideration when dealing with LLMs:

- Training data of the LLM.

- Uncertainty in response, since an identical prompt can give two different answers.

- Size of the model used; the bigger it is, the better it could comprehend the given task.

- Hallucinations, which occur when the model is unsure of the answer.

This research was performed using the zero-shot technique, where the prompt is given directly to, in this case, ChatGPT, model GPT-5. Although it could be said that it performed well while grading, there were some situations that could be handled better. As it was mentioned in [24], one promise of integrating LLMs into education lies in their capacity to provide feedback. Apart from the grade, the LLM response contained a detailed explanation of the grading by provided criteria. In some cases, the grading was harsh, which could be marked as a gross mistake. As it was stated in [25], from a comprehensive perspective, there are still issues with consistency and reliability. The reasons for this could be found in the generated answer, and the LLM could be provided with an explanation of why what it generated was a mistake. This is time-consuming, so there is another way of fine-tuning the model with a set of previously prepared data of old tests and grading so the model could be trained. According to [26], the fine-tuned models significantly outperformed the base models in accuracy and reliability.

Human grading was used as a reference, which is also imprecise. Grading is always subjective, even when the grader tries to be as objective as possible. There is always a possibility of a human-made mistake while grading, which could go under the radar if it benefits the student. This issue could be less if multiple human graders graded the same student’s assignments using the same criteria. The same is for LLMs; to obtain better results, there should be more models involved in grading.

4.1. Differences Between Crisp and Fuzzy Grading Results

Crisp grading, where the LLM outputs a single numerical score per assignment, generally follows the overall trend of human grading but exhibits notable variability at the individual assignment level. While average deviations remain moderate, crisp LLM grading occasionally overestimates or underestimates student performance, reflecting sensitivity to prompt interpretation and limited ability to represent partial correctness. This approach treats grading decisions as binary or sharply bounded, which reduces expressiveness when student solutions are only partially correct.

In contrast, fuzzy grading produces substantially different behavior. By representing grades as trapezoidal membership functions associated with linguistic categories (poor, good, excellent), fuzzy grading captures uncertainty and partial fulfillment of grading criteria more explicitly. However, the results show that direct fuzzy grading is systematically more conservative than both human and crisp LLM grading. Defuzzified fuzzy scores are consistently lower, especially for mid-range and weaker student solutions, leading to significantly larger deviations, often exceeding 30–50% from human grading.

The key observed difference, therefore, is that crisp grading prioritizes approximation to human scores but lacks nuance, whereas fuzzy grading prioritizes nuanced representation of uncertainty but introduces a strong bias toward harsher evaluation when applied without correction. This divergence highlights that fuzzification alone does not guarantee fairness or alignment with human judgment and motivates the need for fuzzy metric correction mechanisms.

4.2. Limitations of LLMs in Awarding Grades and Differences from Teacher Grading

The main limitations observed during experimentation with LLM grading are the following:

- LLMs lack contextual calibration to a specific cohort;

- LLMs exhibit sensitivity to prompt formulation and internal variability;

- LLMs apply grading criteria more rigidly than teachers;

- LLMs lack accountability and formative intent;

- LLMs do not possess a stable notion of ground truth in grading.

Human teachers implicitly normalize grading by considering the overall performance of a group, the difficulty of a particular assignment instance, and the expected learning outcomes at a given stage of the course. In contrast, LLMs evaluate each submission largely in isolation, relying only on the provided prompt and grading criteria. This absence of cohort awareness contributes to inconsistencies and systematic bias, particularly visible in fuzzy grading results, where mid-range student performance is penalized more severely than in human grading.

Identical student solutions can receive different scores across multiple grading runs, especially in crisp grading. Teachers, while subjective, tend to maintain internal consistency within a grading session and across a student group. This stochastic behavior of LLMs introduces uncertainty that is not directly observable in traditional grading practices. LLMs could be instructed with the specific prompt to be more loose or strict with grading, which can add up to the stochastic behavior of the grader. Especially, the system needs to be resilient to the prompt injection, where a student could try to put a word or sentence in a code that will be an instruction to the LLM.

Human graders often exercise pedagogical judgment, rewarding partial understanding, recognizing creative or unconventional solutions, and compensating minor technical errors when the core algorithmic idea is correct. LLMs, particularly when guided by explicit fuzzy criteria, tend to interpret missing or imperfect elements strictly, resulting in systematically lower scores. This behavior was evident in the fuzzy grading results, where defuzzified scores consistently underestimated human grades.

Teachers award grades not only to quantify performance but also to motivate students and support learning progression. Grading decisions may intentionally favor borderline cases or reflect improvement over time. LLMs, by contrast, optimize for internal consistency with the prompt rather than pedagogical impact, which can lead to grading outcomes that are technically defensible but educationally misaligned.

Human grading, despite being subjective, is anchored in institutional norms, shared experience among instructors, and tacit knowledge of course expectations. LLMs derive their judgments from training data and probabilistic inference, which may not align perfectly with local grading standards unless explicitly calibrated or fine-tuned.

4.3. Comparing with Other Automated Methods and Further Research

Unlike in [27], which uses a classifier to predict the essay grades, FCM is used to cluster the previously graded data. Since three groups were given upfront, their cluster centers are used as a base for correcting the grading formula. Assignment data does not need additional labeling in case of clustering algorithm usage, which makes it usable in this case, where no obvious labeling of the assignments could be achieved.

To compare this method with AES, the difference is that AES has primarily focused on generating a final score for student responses rather than providing detailed feedback [28]. While using ChatGPT for grading, it always gave a detailed explanation of why something was graded as it was, often with suggestions on how the assignment could be corrected. One flaw is that the current explanation is only visible to the grader, not the student. Some sort of AI integration in a web app would be required for the student to see the report as well.

Further research in the field could take grading similar to Massive open online course courses: (1) Instructor grades, (2) Peer grades and (3) ChatGPT grades [29]. Apart from it, multiple instructors or LLMs could be used to grade previously anonymized data using the crisp and/or fuzzy grading criteria. For now, pure LLM grading should be used with human supervision, in case of serious mistake, which can occur while grading. Upgrading to this could be an agentic approach, where an AI agent could choose between multiple grades of the same assignment, do additional checks and correct the grading if needed.

Regarding fuzzy metrics and fuzziness, new approaches could be explored. A great choice of different fuzzy metrics (with appropriate parameters) gives the possibility of obtaining a better description of the research results. The current approach using clustering and grade correction needs to re-scale the results because of the cluster centers that are inside the domain. Also, for the best students to receive the prize of giving them maximal points, a correction factor needed to be powered, and all of these were human decisions along the way. Also, another thing that could be handled by an AI agent in the future, if needed.

Overall, this is one new method to grade students’ programming assignments. It benefits in the way that it lowers teachers’ time spent with manually testing and grading programming assignments. Additionally, instructors have the opportunity to spend more time giving feedback and revising students’ work [30].

5. Conclusions

This paper presented a hybrid framework for grading programming assignments that incorporates fuzzy metrics in LLMs. The motivation was to overcome the limitations of both traditional manual grading and existing automated approaches, which often rely on crisp evaluation and fail to capture partial correctness, stylistic quality, and uncertainty inherent in student solutions.

The proposed approach leverages LLMs to perform semantic analysis of student code according to predefined grading criteria, producing fuzzy evaluations expressed through linguistic variables and trapezoidal membership functions. These fuzzy grades are subsequently defuzzified and refined using fuzzy distance measures and FCM clustering, enabling adaptive grade correction based on the structure of historical grading data.

Experimental results on real course data indicate that crisp LLM grading can approximate human grading but exhibits notable variability. Fuzzy grading provides a more nuanced representation of student performance; however, when applied directly, it tends to be overly strict. The introduction of fuzzy metric correction improves alignment with human grading, particularly for higher-performing students, while preserving interpretability and transparency. These findings confirm that fuzzy logic is well suited for modeling uncertainty and partial correctness in programming assessment and that LLMs offer effective semantic analysis and feedback generation capabilities.

Several limitations remain. The results depend on prompt design, model variability, and parameter selection within fuzzy metrics and clustering methods. Moreover, human grading itself is inherently subjective, which limits the notion of an absolute ground truth. Consequently, automated grading systems based on LLMs should currently be applied with human oversight, especially in high-stakes assessment contexts.

Future work will focus on fine-tuning language models using historical graded data, exploring alternative fuzzy metrics and aggregation operators, and automating parameter calibration. The proposed framework represents a step toward fairer, more transparent, and pedagogically aligned automated grading systems, with potential applicability beyond introductory programming courses to other domains requiring nuanced evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R. and S.P.; methodology, N.R.; software, R.R.; validation, R.R. and S.P.; formal analysis, R.R.; investigation, R.R.; resources, R.R.; data curation, R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.; writing—review and editing, N.R. and S.P.; visualization, R.R.; supervision, S.P.; project administration, S.P.; funding acquisition, N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is partially supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, #GRANT no. 7632, the project Mathematical Methods in Image Processing under Uncertainty, MaMIPU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author due to institutional regulations.

Acknowledgments

The third author wants to acknowledge funding from the project MaMIPU. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT (GPT-5.1) for the purpose of grading students’ assignments. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| FCM | Fuzzy C-Means |

| AES | Automated Essay Scoring |

| ASAG | Automated Short Answer Grading |

References

- Douce, C.; Livingstone, D.; Orwell, J. Automatic test-based assessment of programming: A review. J. Educ. Resour. Comput. 2005, 5, 4-es. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Calatayud, V.; Prendes-Espinosa, P.; Roig-Vila, R. Artificial Intelligence for Student Assessment: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, T.; Zhang, D.; Simoulin, A.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Teng, Z.; Qian, X.; Yang, G.; Luo, J.; et al. Code to Think, Think to Code: A Survey on Code-Enhanced Reasoning and Reasoning-Driven Code Intelligence in LLMs. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Suzhou, China, 4–9 November 2025; pp. 2586–2616. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, R. An application of fuzzy sets in students’ evaluation. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1995, 74, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-M.; Lee, C.-H. New methods for students’ evaluating using fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1999, 104, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, D. Fuzzy set approach to the assessment of student-centered learning. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2000, 43, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weon, S.; Kim, J. Learning achievement evaluation strategy using fuzzy membership function. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Frontiers in Education Conference. Impact on Engineering and Science Education, Reno, NV, USA, 10–13 October 2001; Volume 37, p. T3A-19. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial intelligence in higher education: The state of the field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodén, J. Grading exams using large language models: A comparison between human and AI grading of exams in higher education using ChatGPT. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2025, 51, 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaretsky, T.; Ariely, M.; Cukurova, M.; Alexandron, G. Teachers’ trust in AI-powered educational technology and a professional development program to improve it. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 53, 914–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.G.; Latif, E.; Wu, X.; Liu, N.; Zhai, X. Applying large language models and chain-of-thought for automatic scoring. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirtekin, E. Large Language Model-Powered Automated Assessment: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoyuan, C.; Nuobei, S.; Ling, C.; Raymond, L. Enhancing educational Q&A systems using a Chaotic Fuzzy Logic-Augmented large language model. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 1404940. [Google Scholar]

- George, A.; Veeramani, P. On some result in fuzzy metric spaces. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1994, 64, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramosil, I.; Michalek, J. Fuzzy metric and statistical metric spaces. Kybernetika 1975, 11, 326–334. [Google Scholar]

- Deza, M.M.; Deza, E. Encyclopedia of Distances; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ralević, N.; Karaklić, D.; Pištinjat, N. Fuzzy metric and its applications in removing the image noise. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 12049–12061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralević, N.; Delić, M.; Nedović, L. Aggregation of fuzzy metrics and its application in image segmentation. Iran. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 19, 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bezdek, J.C.; Ehrlich, R.; Full, W. FCM: The fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm. Comput. Geosci. 1984, 10, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, E.P.; Mesiar, R.; Pap, E. A characterization of the ordering of continuous t-norms. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1997, 86, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introducing GPT-5. Available online: https://openai.com/index/introducing-gpt-5/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Hackl, V.; Müller, A.E.; Granitzer, M.; Salier, M. Is GPT-4 a reliable rater? Evaluating consistency in GPT-4’s text ratings. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1272229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, A.; Barrett, A.; Escalante, J. Large language models and automated essay scoring of English language learner writing: Insights into validity and reliability. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.W.; Boey, M.; Tan, Y.Y.; Jia, A.H.S. Evaluating large language models for criterion-based grading from agreement to consistency. Npj Sci. Learn. 2024, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Hwang, T.; Jung, J.; Hyeonseok, K.; Namgoong, H.; Lee, Y.; Jung, S. Large Language Models as Evaluators in Education: Verification of Feedback Consistency and Accuracy. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gayed, J.M. Effectiveness of Large Language Models in Automated Evaluation of Argumentative Essays: Finetuning vs. Zero-Shot Prompting. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2024, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; Palma, D. An LLM-based hybrid approach for enhanced automated essay scoring. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, D.; Sanampudi, S.R. A Multitask Learning System for Trait-based Automated Short Answer Scoring. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impey, C.; Wenger, M.; Garuda, N.; Golchin, S.; Stamer, S. Using Large Language Models for Automated Grading of Student Writing About Science. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.; Tan, S.; Tan, S. ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.