Abstract

We consider the minimization of a functional of the calculus of variations, under assumptions that are diffeomorphism invariant. In particular, a nonuniform coercivity condition needs to be considered. We show that the direct methods of the calculus of variations can be applied in a generalized Sobolev space, which is in turn diffeomorphism invariant. Under a suitable (invariant) assumption, the minima in this larger space belong to a usual Sobolev space and are bounded.

Keywords:

calculus of variations; direct methods; invariance by diffeomorphism; quasilinear elliptic equations MSC:

49J10; 35J20

1. Introduction

Let be a bounded and open subset of , and let . As a model example, consider a functional

of the form

where , is continuous and

is a Carathéodory function such that

According to the well-known results (see [1]), the functional f is lower semicontinuous with respect to the weak topology of . However, because of the lack of coercivity of the principal part, we cannot expect that the functional f admits a minimum in (see also the next Example 1). On the other hand, results on the minimization of functionals with a lack of coercivity can be found in [2,3,4,5,6,7], where it is proved, under suitable assumptions, that a minimum exists in a larger Sobolev space.

Our aim is to consider a case with the feature of being diffeomorphism invariant. More precisely, denote by the set of diffeomorphisms of class such that . Then, if we set , we formally have in the model case

where

Therefore, the structure of the functional is invariant, and also satisfy our assumptions if and only if do the same.

An important application of variational methods is the study of continuum mechanics, when a stored-energy function occurs (see [8]). In the one-dimensional case (), it is today standard to consider the case in which the target space of u is a differentiable manifold. In several variables (), this is not at all the case, particularly for existence theorems, and a first step, in view of this kind of application, is to consider scalar problems where the target space of u (in fact ) is treated just as a differentiable manifold (see also Appendix of [9]). This means that one cannot take advantage of the full structure of , and the fact that the setting must be diffeomorphism invariant expresses such a restriction.

With respect to the mentioned papers, it is clear that a quantitative assumption like

already considered in [2,3,4,5,6,7], is not diffeomorphism invariant.

Remark 1.

The question of invariant formulations has been already treated in [10] for quasilinear elliptic equations which are not, in general, the Euler–Lagrange equation of some functional. In such a case, also a uniform coercivity assumption can be considered. For instance, if we start from an equation of the form

and we write , we obtain

which can be written as

where

Different from [2,3,4,5,6,7], the setting of Sobolev spaces is not convenient for our purposes. First of all, is not diffeomorphism invariant, unless or . Moreover, also in the case , the space is too small, as we have no estimate of the rate of degeneration of the principal part (see again Example 1 and also Remark 3). On the contrary, the space , already considered in [11,12,13] for the study of quasilinear elliptic equations with the right-hand-side measure, is much more suitable. First of all, it is easily seen that if and only if .

Let us state our main result, for the model case.

Theorem 1.

Let be endowed with the topology of the convergence in measure and define according to (1).

Then, f is lower semicontinuous with and the set

is compact (possibly empty), for all . In particular, the functional f admits a minimum in .

Moreover, if is any minimizing sequence, then there exist a subsequence and a minimum u such that is strongly convergent to in , for all .

Let us point out that it may happen that each minimum u of the functional f considered in Theorem 1 satisfies , for all , even when (see Example 1). On the other hand, under further (invariant) assumptions, each minimum of f belongs to (see Theorem 9).

In the end, the existence of a minimum follows in a direct way from a basic result (see (Proposition 1.2.2 of [1]) or (Theorem of I.1.1 [14]), while our task will be to prove some results on lower semicontinuity and coercivity in the setting of the spaces . The strong convergence of in is related to the strict convexity of the function

In our setting, the main tool is provided by Theorem 3. Let us point out that results in this direction have been already obtained in [15,16,17].

Actually, Theorem 1 is a particular case of Theorems 6 and 7, where more general functionals of the form

with , are considered.

It would be interesting, as a further development, to consider also critical points, not only minima, under diffeomorphism-invariant assumptions. Let us point out that some results in this direction have been already obtained in [18].

In the next section, we recall some preliminary facts, while Section 3 is devoted to a lower semicontinuity result in the space and Section 4 to the a.e. convergence of under a strict convexity assumption. Section 5 and Section 6 are concerned with some coercivity results in our setting, while Section 7 contains the main results. Finally, in Section 8, we prove some regularity results for the minima of the functional, and in Section 9 we prove that each minimum of the functional satisfies a suitable form of the Euler–Lagrange equation.

2. Notations and Preliminaries

In the following, will denote the -algebra of Lebesgue measurable subsets of , and the -algebra of Borel subsets of . With the terms “measurable” and “negligible”, we mean “Lebesgue measurable” and “Lebesgue negligible”, respectively. Moreover, we denote by the positive and negative parts of a real number s and by the usual -norm.

For every , we define by

Then, if is an open subset of and , we denote by the set of (classes of equivalence of) functions such that for all and such that the set is negligible. We also denote by the set of such that for all . Finally, we denote by the set of such that, for every , there exists a sequence in converging to in with converging to in (see [11]).

According to [13], each with admits a Borel and -quasi continuous representative , defined up to a set of null p-capacity. Thus, the set has a null measure but could have a strictly positive p-capacity. Moreover, for every , there exists one and only one measurable (class of equivalence) such that a.e. in . If and , it turns out that and a.e. in .

Of course, we have

We also write if is an open subset of such that the closure is a compact subset of .

3. Lower Semicontinuity

This section is devoted to an adaptation of the main result of [19] (see also (Theorem 2.3.1 of [1])) to our setting. Let be an open subset of and let

be a function. For every and , we define

by

and we define by . It is easily seen that

Throughout this section, we assume the following:

- (L1)

- The function L is -measurable;

- (L2)

- There exists a negligible subset N of Ω such that:

- For every , the function is lower semicontinuous on ;

- For every , the function is convex on ;

- (L3)

- There exist and a negligible subset of Ω such that , for all .

It is clear that also satisfies (L1)–(L3), for all .

Theorem 2.

Let and let be a sequence in such that is weakly convergent to in , for all and all .

Then, we have

Proof.

Without loss of generality, we may assume that in assumption (L3). Given and , let and , and set

Since

we have

Then, it follows that

Since also satisfies (L1)–(L3), from [19] or (Theorem 2.3.1 of [1]) we infer that

and the assertion follows by the arbitrariness of h and . □

4. The Effect of Strict Convexity

Throughout this section, we assume that is an open subset of and that

satisfies (L1), (L3) and the following:

- (L′2)

- There exists a negligible subset N of Ω such that we have the following:

- For every , the function is continuous on ;

- For every , the function is strictly convex on .

Again, it is clear that also satisfies (L′2), for all .

Theorem 3.

Let and let be a sequence in such that is weakly convergent to in , for all and all . Assume also that

Then, is strongly convergent to in and there exists a subsequence such that is convergent to a.e. in Ω.

For the proof, we need some elementary results.

Proposition 1.

Let be a convex function and let be defined by

Then ψ is nondecreasing.

Proposition 2.

Let

be a continuous function such that is strictly convex, for all .

Let and let be a sequence in such that

Then we have

Proof.

For every , let us set

If and we apply Proposition 1 to the convex function

from , we infer that

Of course, the inequality also holds if , whence

Up to a subsequence, is convergent to some , whence

From the strict convexity of we infer that , so that is convergent to . Since it is either or , the assertion follows. □

Proof of Theorem 3.

Without loss of generality, we may assume that in assumption (L3). Moreover, up to a first subsequence, we have that is convergent to u a.e. in . Let with for a.a. .

First of all, we claim that, for every , there exists such that

Actually, for every , there exists such that

It follows

On the other hand, by dominated convergence we also have that

Finally, if we set

then satisfies (L1)–(L3), and we have that

Now we claim that there exists a subsequence such that

a.e. in . Actually, from (4), we infer that for every there exists such that

Then, for every , there exists such that

It follows that

and hence a.e. in , up to a subsequence. Then, up to a subsequence, we infer that

a.e. in and (5) follows.

Thus, along a suitable subsequence , we have that

a.e. in .

From assumption (L′2) and Proposition 2, we infer that is convergent to a.e. in .

Since

from Fatou’s lemma, it follows that is strongly convergent to in . As usual, since the limit is independent of the subsequence, we have the convergence of the full sequence in . □

5. Nonuniform Coercivity

Throughout this section, we assume that is an open subset of and that

satisfies (L1) and (L3).

Moreover, given , we suppose that L satisfies the assumption (L4,p) defined as follows:

- (L4,p)

- In the case : for every , there exist , and a negligible subset of Ω such thatfor all with ;

- (L4,1)

- For every , there exist and a negligible subset of Ω such thatfor all with .

It is clear that also satisfies (L4,p), for all .

Theorem 4.

Let and let be a sequence in such that

Then, there exist a measurable function and a subsequence such that the following hold:

- and , for all ;

- is convergent to u a.e. in Ω and is weakly convergent to in , for all .

Proof.

Let us treat only the case . The case is similar and simpler. The argument is an adaptation of the proof of (Theorem 4 of [20]). Without loss of generality, we may assume that in assumption (L3).

First of all, from (L4,1), we infer that

Therefore, the sequence is bounded in , for all . It follows that there exists a measurable function and a subsequence such that is convergent to u a.e. in .

Let and let be such that

Again by (L4,1), for every there exists such that

Let

with and satisfying , and let be such that . Finally, let .

Then, we have

It follows that

whence

If E is a measurable subset of such that , then for every , we have

According to (Theorem 1.2.8 of [1]), we have that , and is weakly convergent to in . □

6. Further Coercivity from the Lower Order Part

Throughout this section, we assume that is an open subset of , that , and that

satisfies (L1),(L3), (L4,p) and

- (L5)

- we have

Again, it is clear that also satisfies (L5), for all .

Theorem 5.

Let and let be a sequence in such that

Then, there exist and a subsequence such that is convergent to u a.e. in Ω and is weakly convergent to in , for all .

Proof.

Let u and be as in Theorem 4. If we set

then, by (L3) and (L5), there exists a negligible subset N of such that

for all and all . From Fatou’s lemma we infer that

where denotes the upper integral (see [1]). From (6), we infer that for a.a. , whence and the assertion follows. □

Corollary 1.

Let , and let be a sequence in such that

Then, there exist and a subsequence such that is convergent to u a.e. in Ω and is weakly convergent to in , for all .

Proof.

It easily follows from the previous result. □

7. Existence of Minima

In this section, we prove the main results.

Theorem 6.

Let Ω be an open subset of , let , and let

be a function satisfying (L1)–(L3), (L4,p) and (L5). Assume also that .

Let be endowed with the distance

and define by

Then f is lower semicontinuous with and the set

is compact (possibly empty), for all .

In particular, the functional f admits a minimum in .

Proof.

By assumptions (L1) and (L3), the functional f is well defined, and it is obvious that . Let now and let be a sequence in such that . From Corollary 1, we infer that there exist and a subsequence such that is convergent to u a.e. in , and is convergent to weakly in , for all and all . In particular, we have

and, by Theorem 2,

so that

is sequentially compact. Since is a metric space, the remaining assertions follow. □

Theorem 7.

Let Ω be an open subset of , let , let

be a function satisfying (L1), (L′2), (L3), (L4,p) and (L5), and let be defined as before.

Then, for every minimizing sequence , there exist a subsequence and a minimum u such that is convergent to u a.e. in Ω, and is strongly convergent to in , for all .

Proof.

Without loss of generality, we may assume that in assumption (L3). Arguing as in the previous proof, we can find and a subsequence such that is convergent to weakly in , for all and all . This time, we infer that

so that u is a minimum of f and, by Theorem 3, is strongly convergent to in , while is convergent to a.e. in , up to a further subsequence.

According to assumptions (L3) and (L4,p), for every , we have

for some and . From the (generalized) Lebesgue’s theorem, we conclude that is strongly convergent to in . □

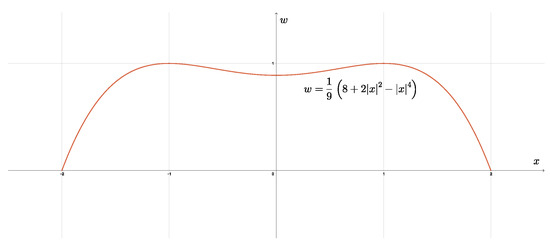

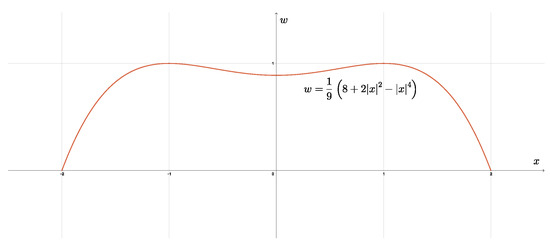

Example 1.

Figure 1.

The graph of in the case .

Then, we have whenever and for .

If is the convex function defined by

it turns out that

Now, define first by

where is the -function defined by

It is easily seen that

and that is lower semicontinuous, strictly convex, proper and coercive. Therefore has one and only one minimum point, which is just , as

Let now be a -function such that

and let be the primitive of such that . We have that

and that

Therefore, if we set and

it turns out that L is of class on and that the assumptions of Theorem 1 are satisfied. In particular, hypotheses (L1), (L′2), (L3), (L4,p) with and (L5) hold. On the other hand, the functional

has one and only one minimum point , which is given by . Therefore, we have and

whence

for all . It follows that , for all (see, e.g., (Theorem 3.77 of [21])).

Example 2.

Let be a -function such that whenever and whenever . Let again and define first by

where is the -function defined by

It is easily seen that

and that is lower semicontinuous, strictly convex and coercive. Therefore has one and only one minimum point, which is just . Moreover, if we set

it turns out that

Let now again ν and ψ be defined as in Example 1. We have

Moreover, if we set and

it turns out that L is of class on and that assumptions (L1), (L′2), (L3), and (L4,p) with are satisfied. On the other hand, the functional

has no minimum point in , because

but , for all . In this case, assumption (L5) is not satisfied.

Remark 2.

As already observed in the Introduction, after proving the lower semicontinuity and the coercivity of the functional in a suitable functional setting, the existence of a minimum follows in a standard way. More precisely, (L1)–(L3) are the natural assumptions to ensure the lower semicontinuity, while (L4,p) and (L5) imply the coercivity. Assumption (L′2) is the typical stronger variant of (L2), designed to obtain the strong precompactness of the minimizing sequences.

Let us point out that (L5) is essential for the coercivity, according to Example 2, in which (L5) is not satisfied and the functional admits no minimum.

This is the basic set of assumptions for minimization. In the next sections, we will consider other assumptions either to ensure that each minimum is more regular or to prove that it satisfies a suitable form of the Euler–Lagrange equation.

Remark 3.

Let us point out that, under the assumptions (L1), (L′2), (L3), (L4,p) and (L5), it may happen that the functional admits no minimum in . Actually, by Example 1, the situation is even worse. It may happen that each minimum u satisfies , for all . Of course, this implies that , but even that the minimization cannot be reduced to a Sobolev setting “up to diffeomorphism”.

8. Regularity of Minima

Throughout this section, we assume that is a bounded and open subset of , that , and that

satisfies (L1) and .

Theorem 8.

Assume there exist , and a negligible subset N of Ω such that

for all . Let be such that

Then there exists such that .

Proof.

Of course, assumption (L3) also is satisfied. If we set , we have

Since

it follows that , whence , as is bounded. □

Theorem 9.

Assume that and that there exist , , , and a negligible subset N of Ω such that

for all , where . Let be such that

Then we have .

Proof.

If we set , we have

As before, we deduce that . Then, from Theorem A1 in the Appendix A we infer that , whence . □

It is easily seen that also the assumptions of the previous results are invariant by diffeomorphism.

Remark 4.

It and , then we have

with . Therefore, intermediate powers , with , can be estimated in terms of and , with the correct summability of the coefficients.

9. Euler–Lagrange Equation

Throughout this section, we assume that is an open subset of , that and that

is a function such that the following hold:

- (L6,p)

- There exists a negligible subset N of Ω such that we have the following:

- For every , the function is measurable on Ω;

- For every , the function is of class on ;

- For every , there exist , and such thatfor all with .

As usual, it follows that also satisfies (L6,p), for all .

Let denote the set of in vanishing a.e. outside some compact subset of . Then, following an idea of [22], for every , we denote by the linear space of in such that u is essentially bounded on . For instance, if and , then .

For every , every and every measurable function v, we set also

The next assertions are easily proved.

Proposition 3.

For every , and , the following facts hold:

- (a)

- We have

- (b)

- We have and the linear map is a bijection of onto ;

- (c)

- We havea.e. in Ω.

Theorem 10.

Let be such that

Then we have

Proof.

It easily follows from Lebesgue’s Theorem. □

Now, for every and , we define the linear space

We remark that , for all , and we set

Moreover, if , it turns out that

Therefore, we have for all and the linear map is a bijection of onto . As before, we also have

a.e. in , for all , and .

Theorem 11.

Let be such that

Then we have

(both sides could be ).

Proof.

Let us first treat the case , namely . In this case the argument is an adaptation of the proof of (Theorem 4.7 of [23]). Assume, for instance, that . Let be a -function such that whenever , and whenever . Then, and we have

Since

from Fatou’s Lemma, we infer that

whence . Coming back to (7), from Lebesgue’s Theorem, we conclude that

If , the argument is similar.

Consider now the general case. Let and let . If we set , it follows that , while

From the previous step, we infer that

and the assertion follows. □

Remark 5.

If is positively homogeneous of degree p and we have

for some , then it follows that

Therefore, the assumption

is implied by .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and M.M. All the authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are members of the Gruppo Nazionale per l’Analisi Matematica, la Probabilità e le loro Applicazioni (GNAMPA) of the Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica (INdAM).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Throughout this appendix, we assume that is a bounded and open subset of , that , and that

satisfies (L1). We aim to prove the next result.

Theorem A1.

Assume there exist , , and a negligible subset N of Ω such that

for all . Let be such that

Then we have .

If the expression is replaced by with and , then the assertion is essentially contained in (Theorem 5.3.2 of [24]). We aim to prove that the limit exponents are allowed. A related result, when the estimates are independent of x, is contained in [25].

For the proof, we need to adapt some well-known results from [6,26,27,28,29].

Lemma A1.

Let be three measurable functions such that

where

Then we have

whenever is nondecreasing.

Proof.

Since

from the monotone convergence theorem, we infer that we also have

whence

as is nondecreasing. Arguing on the measures and , we conclude that

which provides the required formula. □

Lemma A2.

Let and let , and be such that

where

Then, there exists such that if

then and

Proof.

First of all, it is easily seen that we also have

From Lemma A1, we infer that

whenever is nondecreasing.

Given , let be the -function such that and

Then and, for every , we have

Since is nondecreasing on , it follows that

whence

If we set

it follows that

Therefore, if we set

and we have

namely

it follows

whence

Going to the limit as , we infer that and

as required. □

Lemma A3.

Let and let , and be such that

Then we have .

Proof.

Let be as il Lemma A2 and let with

It follows that

with

If , we infer that by Lemma A2. If , then there exists a finite sequence such that

The iteration of Lemma A2 shows that , whence by a further step. □

Lemma A4.

Let and let , be such that

Then we have .

Proof.

The statement in the case is a step of the proof of (Theorem 4.1 of [29]), while the general case is a step of the proof of (Theorem 1.1 of [26]). □

Lemma A5.

Let

and let , , and be such that

Then we have .

Proof.

If we set , from we infer that . If we set , and , we have

with and . Since , from Lemma A3, we infer that for all . It follows that

with

for some . By Lemma A4, we conclude that . □

Proof of Theorem A1.

Since

we have

From Lemma A5, we infer that . □

References

- Buttazzo, G. Semicontinuity, Relaxation and Integral Representation in the Calculus of Variations; Pitman Research Notes in Mathematics Series; Longman Scientific & Technical: Harlow, UK, 1989; Volume 207. [Google Scholar]

- Aharouch, L.; Bennouna, J.; Bouajaja, A. Existence and regularity of minima of an integral functional in unbounded domain. Aust. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2015, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aharouch, L.; Bennouna, J.; Bouajaja, A. Minima of some integral functional: Existence and regularity. Nonlinear Dyn. Syst. Theory 2016, 16, 335–349. [Google Scholar]

- Arcoya, D.; Boccardo, L. A class of integral functionals with a -minimum. Atti Accad. Naz. Lincei Rend. Lincei Mat. Appl. 2022, 33, 535–551. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardo, L.; Croce, G.; Orsina, L. minima of noncoercive functionals. Atti Accad. Naz. Lincei Rend. Lincei Mat. Appl. 2011, 22, 513–523. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardo, L.; Orsina, L. Existence and regularity of minima for integral functionals noncoercive in the energy space. Ann. Sc. Norm. Super.-Pisa-Cl. Sci. 1997, 25, 95–130. [Google Scholar]

- Mercaldo, A. Existence and boundedness of minimizers of a class of integral functionals. Boll. dell’Unione Mat. Ital. 2003, 6, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, J.E.; Hughes, T.J.R. Mathematical Foundations of Elasticity; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Milnor, J.W. Topology from the Differentiable Viewpoint; Princeton Landmarks in Mathematics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdan, J.L.; Kramer, R.J. Invariant criteria for existence of solutions to second-order quasilinear elliptic equations. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1978, 31, 619–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénilan, P.; Boccardo, L.; Gallouët, T.; Gariepy, R.; Pierre, M.; Vázquez, J.L. An L1-theory of existence and uniqueness of solutions of nonlinear elliptic equations. Ann. Sc. Norm. Super.-Pisa-Cl. Sci. 1995, 22, 241–273. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardo, L.; Gallouët, T.; Orsina, L. Existence and uniqueness of entropy solutions for nonlinear elliptic equations with measure data. Ann. L’Inst. Henri Poincaré (C) Anal. Non Linéaire 1996, 13, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Maso, G.; Murat, F.; Orsina, L.; Prignet, A. Renormalized solutions of elliptic equations with general measure data. Ann. Sc. Norm. Super.-Pisa-Cl. Sci. 1999, 28, 741–808. [Google Scholar]

- Struwe, M. Variational Methods; Ergebnisse der Mathematik und Ihrer Grenzgebiete; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardo, L.; Gallouet, T. Compactness of minimizing sequences. Nonlinear Anal. 2016, 137, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezis, H. Convergence in D′ and in L1 under strict convexity. In Boundary Value Problems for Partial Differential Equations and Applications; Lions, J.L., Baiocchi, C., Eds.; RMA Research Notes in Applied Mathematics; Masson: Paris, France, 1993; Volume 29, pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Visintin, A. Strong convergence results related to strict convexity. Commun. Partial Differ. Equ. 1984, 9, 439–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solferino, V.; Squassina, M. Diffeomorphism-invariant properties for quasi-linear elliptic operators. J. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2012, 11, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ioffe, A.D. On lower semicontinuity of integral functionals. II. SIAM J. Control Optim. 1977, 15, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degiovanni, M.; Marzocchi, M. Multiple critical points for symmetric functionals without upper growth condition on the principal part. Symmetry 2021, 13, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, L.; Fusco, N.; Pallara, D. Functions of Bounded Variation and Free Discontinuity Problems; Oxford Mathematical Monographs; The Clarendon Press Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Degiovanni, M.; Zani, S. Euler equations involving nonlinearities without growth conditions. Potential Anal. 1996, 5, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellacci, B.; Squassina, M. Unbounded critical points for a class of lower semicontinuous functionals. J. Differ. Equ. 2004, 201, 25–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladyzhenskaya, O.A.; Ural’tseva, N.N. Linear and Quasilinear Elliptic Equations; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Cianchi, A. Boundedness of solutions to variational problems under general growth conditions. Commun. Partial Differ. Equ. 1997, 22, 1629–1646. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardo, L.; Giachetti, D. Alcune osservazioni sulla regolarità delle soluzioni di problemi fortemente non lineari e applicazioni. Ric. Mat. 1985, 34, 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Giachetti, D.; Porzio, M.M. Local regularity results for minima of functionals of the calculus of variation. Nonlinear Anal. 2000, 39, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbarg, D.; Trudinger, N.S. Elliptic Partial Differential Equations of Second Order; Classics in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stampacchia, G. Le problème de Dirichlet pour les équations elliptiques du second ordre à coefficients discontinus. Ann. Inst. Fourier (Grenoble) 1965, 15, 189–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).