Abstract

The aim of this research is to minimize the number of container-rehandling operations in both the yard and on the ship in order to solve the problem of coordinated optimization of ship loading and yard container retrieval and enhance the loading efficiency of automated container terminals,. An optimization model that integrates the optimized decision-making of both the container retrieval order from the yard and the ship’s space allocation is developed, and an improved cuckoo algorithm is employed to solve the optimization problem. This paper examines the influence of container retrieval order from the yard on rehandling within the yard, as well as the effect of the ship’s space allocation on subsequent rehandling operations at the unloading port. Experimental results demonstrate that the solution derived from the comprehensive optimization model based on the improved cuckoo algorithm considerably reduces the overall number of overturned containers. This confirms that the proposed optimization model effectively enhances loading efficiency and reduces container rehandling both in the yard and on the ship. The analysis of experimental results indicates that the model and algorithm proposed in this paper have certain applicability.

Keywords:

container terminals; container space allocation; stowage planning; improved cuckoo algorithm MSC:

49K10

1. Introduction

In recent years, the national “Belt and Road” initiative has underscored the status of the Yangtze River as a crucial waterway. As the shipping market expands, container transportation, currently the primary method of cargo transport, has seen significant advancements. This mode of transport is noted for its low costs, high safety and reliability, rapid loading and unloading, and minimal environmental impact. Liner shipping is vital for freight transportation and international maritime trade, and the economic development of various countries heavily relies on the movement of containerized goods. In container liner transportation, ship stowage is a crucial element that supports the efficient and smooth operation of the container transport network. Proper stowage directly affects wharf operation efficiency and safety, as well as the revenue and safe navigation of ships. Effective stowage decision-making is essential for protecting the interests of both ports and shipping companies [1]. Therefore, enhancing box space allocation and stowage planning through scientific methods and effective management is vital for improving port operation efficiency and competitiveness.

In the field of containerization, advancements in technology, equipment, and artificial intelligence have led to the maturation of automated container terminal technology. Compared with traditional container terminals, automated terminals offer two significant advantages: higher overall wharf operation efficiency and lower labor costs [2]. In December 2017, the fourth phase of the Shanghai Yangshan Automated Container Terminal was officially completed and became operational. This terminal is the largest ultra-large container terminal in the world. By 2020, just three years after its opening, Yangshan Phase IV surpassed 4 million TEUs in container throughput for the first time, accounting for approximately one tenth of the total throughput of the Shanghai port area.

Automated container terminals are characterized by their large operational and environmental scale, complex processes, and relatively small number of on-site operators. There is significant potential for improving actual operational costs and efficiency, and further research is needed to advance the intelligence of automated container terminals [3]. However, owing to site constraints, it is not feasible to indefinitely increase the amount of operating equipment. Therefore, optimizing task scheduling at the terminal from a system-wide perspective is essential for enhancing overall wharf efficiency.

In container water transportation, owing to the economic nature of the process, containers are stacked both in the yard and on ships. However, considering that containers often need to be transported to different ports, coordinating the order of container pickup in the yard and container placement on the ship is crucial. This coordination aims to minimize container reversals, thereby reducing the ship’s port stay time and lowering operating costs. This leads to two sub-problems: the container ship loading sequence problem (CLSP, also known as the container yard picking order problem) and the container ship stowage problem (CSP). The CSP is typically addressed in two stages: The first stage is the pre-stowage phase, in which the entire container ship is considered, and the goal is to match individual containers with specific ship bays. This approach is also known as the master bay stowage plan. The second stage is the bay box arrangement phase, which focuses on a single bay and involves arranging containers within that bay according to the pre-stowage plan. This stage is referred to as the slot stowage plan (SSP) [4]. There are relatively few collaborative studies on the CLSP and the SSP, particularly in the context of automated container terminals. Both sub-problems are crucial to the container loading process, and they influence and constrain each other. Therefore, a collaborative study of CLSP and SSP is necessary to effectively address these interrelated issues.

Owing to the large scale, complex constraints, and stringent time requirements of ship stowage scenarios, current manual stowage processes struggle to meet the growing demands for timely and optimal solutions. This has become a bottleneck in enhancing the efficiency of automated container terminal operations [5]. Therefore, it is essential to develop more suitable and efficient optimization methods to automate ship stowage, reduce time requirements, and provide improved stowage plans, thereby increasing the efficiency of automated container terminal operations.

In summary, balancing various factors is essential for making scientific and reasonable decisions regarding container space allocation and stowage planning at busy automated container ports. This paper addresses the collaborative optimization problem of ship stowage and yard picking order at automated container terminals by establishing a mathematical programming model to achieve comprehensive optimization of both yard picking order and ship stowage. Additionally, the paper develops an improved cuckoo search (ICS) algorithm tailored to the characteristics of automated container ports. The primary goal of this study is to assist automated container ports and shipping companies in making real-time decisions regarding ship scheduling.

The innovative aspects of this paper include the following: (1) combining yard space allocation and terminal loading for a comprehensive analysis, (2) examining multi-berth loading of container ships, and (3) combining heuristic algorithm rules to generate initial solutions and propose an improved cuckoo algorithm.

2. Related Work

In the container transportation network, container terminals serve as crucial hubs, connecting container waterway transportation with land transport and considerably impacting the overall transportation system [6]. As container transportation volumes continue to rise, addressing the challenge of reducing ship operating times in the harbor and enhancing terminal efficiency has become increasingly urgent. The traditional operation model for container terminals can no longer meet the future development needs of the industry. As a result, an increasing number of international ports are constructing automated container terminals to address new demands. The automated container ship loading problem is a complex, multi-objective, multi-constraint optimization challenge that has been proven to be NP-hard [7]. Key issues in planning for automated container terminals include shore bridge scheduling, ship allocation, and yard operation.

In terms of solving this problem, a large number of researchers have begun to study methods, such as Avriel et al. [8], who proposed a dynamic planning mathematical model aimed at minimizing the number of overturned containers. This model considers factors such as the stacking position and weight distribution of containers in the yard. Chen et al. [9] developed a stacking optimization model with a similar objective of minimizing overturned containers and designed a heuristic algorithm based on the containers’ presence time, and used the model to address the problem, incorporating factors such as the destination port of the export containers, weight classes, and operational difficulty. Kim and Park [10] aimed to enhance both yard space utilization and export loading efficiency. To achieve this, a hybrid rolling plan method based on the rolling plan approach was developed to improve yard space utilization. Zhang et al. [11] addressed the box space allocation problem in phases and established a corresponding mathematical optimization model. The first phase focuses on balancing the workload across box areas and allocating containers to different areas, while the second phase aims to minimize the horizontal transportation distance of containers and optimally arrange the container volumes in each box area for allocation to the corresponding ship. Bazzazi et al. [12] extended Zhang’s study by incorporating the stacking of various types of cargo, including ordinary containers, empty containers, and reefer containers, in different box zones, and solved the model using a genetic algorithm. Caaerta et al. [13] developed a binary linear programming model for the yard box space allocation problem with the goal of minimizing the number of overturned containers. The model was solved using a heuristic algorithm, and the results were compared with those from existing methods in the literature to validate the feasibility of the model and algorithm. Li [14] proposed a hierarchical analysis method addressing the limited space and heavy workload of terminal yards in continuous operation. Through field research, Li decomposed the problem into two stages: berth allocation and box area selection. Petering [15] developed several real-time storage systems for containers, considering the uncertainty of container arrivals, and developed an integrated discrete-event simulation model to evaluate container terminals. However, the above literature did not design from the perspective of continuous algorithms.

Some scholars have started to solve this problem through models and corresponding algorithms, such as Scott et al. [16], who investigated the single-destination loading of container ships, classifying containers by destination port and type. An optimization model for container ship loading at terminals was developed, aimed at maximizing container loading and minimizing the number of empty containers. The model also included constraints on longitudinal inclination and stability height, and the problem was solved using a branching and bounding method. Aslidis [17] investigated the multi-port loading of container ships, focusing on scenarios involving either loading or unloading, but not both. The author transformed the container ship loading problem into a “P problem” and established a 0–1 planning model aimed at minimizing the number of empty containers. This approach allowed for adjusting the positions of neighboring containers to regulate the ship stability coefficient. Ambrosino et al. [18] examined single-berth allocation for ships while considering the ship’s time in port, with the ship’s inverted container volume as zero and the ship’s stability as a constraint. A 0–1 integer programming model was developed to address these constraints. Kim et al. [19] proposed a method for calculating overturned containers under ideal conditions, in the presence of a berth, a column, and a c-tier balustrade. Jin [20] introduced three fundamental principles to avoid overturning boxes during pickup in the loading yard, reduce unplanned box-turning operations, and enhance overall terminal efficiency. These methods and principles are applicable in practical operations. Dubrivsky et al. [21] developed a mathematical model to minimize the number of yard movements required for loading a ship. A strategy based on genetic coding within a genetic algorithm was designed to effectively reduce the search space for the algorithm. Ambrosino et al. [22] considered the actual vessel structure and established a 0–1 linear programming model to develop the ship’s allocation plan based on the principle of main-beam priority. To more accurately calculate the loadable area on the ship, it was divided into a collection of small cells. This approach was used in the solution process, and the complexity of the allocation process was effectively reduced. Imai et al. [23] developed a mathematical model with the dual objectives of minimizing the amount of dumping in yards and maximizing ship stability during the loading process. A novel method based on probabilistic theory was proposed for estimating the total amount of dumping in yards. This method is the first to estimate the number of dumped boxes based on the randomness of the timing of export boxes leaving the yard. Tierney et al. [24] investigated the impact of ballast cover on ship dumping, analyzed the complexity of container ship stowage, and developed a mathematical optimization model that incorporated the effect of ballast cover on ship dumping. An improved heuristic algorithm was used to solve this model. Chen et al. [25] examined the scheduling problem of mechanical equipment with the aim of minimizing completion time. A mathematical model for integrating different types of equipment was established to coordinate their operations effectively. However, the above literature rarely designs algorithms based on nonlinear models.

In summary, the collaborative optimization of ship stowage and yard container retrieval is a relatively new area of study. While many researchers have contributed to this field, there is a lack of research that addresses the impact of yard container retrieval sequences on rehandling operations in automated container terminals, as well as the effects of stowage results within ship bays on subsequent rehandling in the unloading port. This paper aims to address this gap by optimizing the collaborative problem of ship stowage and yard container retrieval from the perspective of automated container terminals, integrating both the optimization of yard container retrieval sequences and ship stowage results.

3. Problem Description and Modeling

3.1. Problem Definition

With the increasing size and complexity of ships, the operability and spatial limitations of expansion are important challenges. When expanding automated terminals, it is necessary to consider the limitations of existing terminal space and the potential risk of traffic congestion. Therefore, the specific challenges currently faced by automated container terminal operations mainly include operational safety standards, complexity of ships and operational scale, operability and space limitations of expansion, economic cycle impacts, reduction in actual operational space, and high costs and standardization issues. This article attempts to address some of the challenges in solving the problem described in the problem description. The comprehensive optimization problem of container terminal loading, considering yard space allocation, is described as follows: Export containers are transported from the outer collector yard to the inner yard through the terminal gate. According to the yard space allocation plan for export containers, the gantry cranes retrieve and stack the containers in the designated yard spaces. Once the container ship docks, the loading operation proceeds based on the allocation plan. This process includes retrieving containers from the yard, transporting them horizontally, and moving them onto the ship via the quay crane.

3.2. Model Establishment

3.2.1. Assumptions

According to the problem description, there are many challenges faced by automated container terminals in reality, and some conditions need to be simplified before modeling. To establish a reasonable optimization model for container terminal allocation, the following assumptions are made considering yard space allocation:

(1) The cargo type, container type, destination port, container weight, and volume information for all export containers in the yard are known, and there are multiple berths available for loading onto the container ship.

(2) Information about the container ship structure and the available berths is provided.

(3) Export containers of the same cargo category are stacked in the same box area using a uniform stacking strategy.

(4) All export containers are loaded onto the same vessel, and the number of operational lanes available on the vessel is known.

(5) The terminal has a sufficient and well-configured amount of machinery and equipment (such as quay bridges and yard cranes) to ensure that loading efficiency is not considerably impacted and that the process is not hindered by mechanical breakdowns or maintenance issues.

3.2.2. Symbol Description

The symbols required for the model in this article can be defined as follows (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sets, parameters, and variables used in the studied problem.

3.2.3. Programming Model

The number of times a container is flipped refers to the number of times it needs to be moved from its original position to a new position during container terminal operations in order to meet the requirements of loading or unloading. Flipping is inevitable, especially when loading or lifting containers. If the stacking order of the containers does not match the shipping order, flipping is necessary. The number of times the container is flipped directly affects the operational efficiency and cost of the terminal. The objective of the mathematical model established in this paper is to minimize the total number of container flips, including both during yard handling and during unloading at subsequent ports. The objective function is expressed as follows:

In Equation (1), represents the total number of container flips during unloading at subsequent ports, and represents the total number of container flips in the yard due to the loading sequence. Here, represents the total number of vessel bays, represents the total number of vessel rows, represents the total number of vessel layers, represents the total number of yard slots, represents the total number of yard rows, and represents the total number of yard layers.

The constraints are as follows:

Here, denotes the sum of the weights of containers in the bay of the container ship after stowage is completed in the column ( represents the total number of containers):

Equation (3) specifies that the list moment for each bay in the container ship must remain within an allowable range after loading is completed:

Equation (4) indicates that each container in the yard occupies at most one slot on the ship.

Equation (5) indicates that each container in the yard awaiting loading must occupy exactly one slot on the container ship.

Equation (6) stipulates that containers within bay of the ship cannot be suspended in air. Specifically, if no container is placed in position , then no container should be placed in the position directly above it. That is to say, when the second term on the left side of Equation (6) is 1, the first term must be 1.

Equation (7) specifies that heavier containers must not be stacked on top of lighter containers within the bays of the container ship. Similarly, when the second term on the left side of Equation (7) is 1, the first term must also be 1.

4. Solution Method

4.1. Heuristic Algorithm Design

The model constructed in this article is a nonlinear problem that is difficult to solve using mature commercial solvers such as CPLEX and LINGO, so intelligent algorithms are used for solving. In recent years, some researchers have begun to use the cuckoo algorithm to solve discrete operational plans of enterprises. Although the cuckoo algorithm is designed for continuous problem optimization problems, researchers have begun to use different heuristic rules to convert continuous solution vectors into discrete job plan rankings. For example, Li et al. [26] proposed a new second-order decomposition ensemble (SDE) method based on the cuckoo search algorithm (CSA) for air cargo forecasting, applying ARIMA and the Elman neural network (ENN) optimized by CSA to predict trend and low-frequency components, and in this process, phase space reconstruction (PSR) is performed to determine the input structure of the neural network. The final prediction result is obtained by integrating the predicted values of each component. Li et al. [27] studied the mixed flow shop scheduling problem in sand casting enterprises with multivariate and multi-stage production characteristics, and developed an improved cuckoo algorithm. Considering the “single-batch” coupling relationship in the production process, a single-layer encoding rule based on casting category numbering sorting was designed, and corresponding decoding mechanisms were designed in the batch stage and single-piece processing stage. Minh et al. [28] used two methods for discretization of algorithmic problems, the first of which is based on modifying the concept of random walks with step sizes following a Lévy distribution. The second method is to establish a new equilibrium vector based on the global optimal solution and the worst optimal solution utilized in each iteration. An optimization algorithm called the improved cuckoo search (CS) algorithm, called the new cuckoo balance search (NB-CS), is used to complete the damage identification process in the structure. Therefore, by imitating the method described in the above literature, this article will innovatively use heuristic algorithm rules to generate feasible solutions, and this rule will not change the feasibility of the solution during the algorithm steps.

The container stowage problem at automated container terminals involves multiple container ship bays, yard bays, and various destination ports for export containers. Solely relying on intelligent optimization algorithms to find an optimal solution may result in excessive computation time. Although the research and application of genetic algorithms and ant colony optimization algorithms are relatively mature, they are prone to getting stuck in the state of local optimal solutions. The cuckoo search algorithm has greater comprehensive advantages in terms of parameter count and global optimization ability. The algorithm can be flexibly combined with other algorithms and has a wider applicability. Therefore, by improving the cuckoo search algorithm, its global advantages are demonstrated, and the local optimality of the algorithm is improved by combining other heuristic rules. Therefore, this paper proposes a heuristic algorithm to generate a near-optimal initial solution, followed by the use of an ICS algorithm to refine this solution and explore optimal results, thus enhancing both the speed and the performance of the solution process.

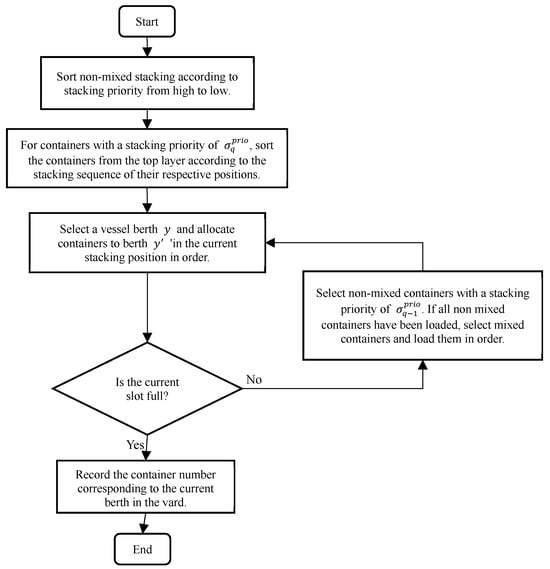

The encoding of the heuristic rules proposed in this section is designed to allocate containers awaiting loading in the yard to the bays of the container ship that are ready for stowage. The goal of these rules is to assign containers from the yard to each bay according to their priority level and to minimize the number of destination ports within mixed-loaded bays. The specific operational steps are as follows:

- According to the specific arrangement of containers awaiting loading in the yard, sort the non-mixed stacks by the priority level of the slots from highest to lowest.

- For non-mixed stacks with the same stacking priority , number and sort the containers according to their position in the stack, starting from the top layer.

- Select containers awaiting loading in the yard with a specific stacking priority , choose an empty bay on the ship that is ready for loading, and assign containers to ship bay in sequence.

- If the selected containers with the specified stacking priority do not fill the chosen bay, continue selecting containers from non-mixed stacks with the next highest priority ;

- Once all non-mixed stacks have been loaded, select containers from mixed stacks and load them in sequence until the bay is filled. Then, proceed to choose the next available bay for loading.

The heuristic rule process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Steps for the heuristic rule procedure.

4.2. Dynamic Selection Strategies for Interactive Information

This paper introduces an ICS algorithm. In each iteration, new nest information is introduced, and the nest position update mechanism incorporates interaction information among nests to ensure diversity in the search process, thereby expanding the search scope. Interaction information reflects fitness differences among individuals, guiding the evolutionary direction of the algorithm and enhancing the precision, speed, and convergence rate of the search. The improved Lévy flight mechanism is described by the mathematical formula shown in Equation (8):

is the total number of nests, are two randomly selected nests, and is the optimal nest identified in the current iteration. The step size factor is defined by Equation (9) as follows:

The mathematical formula for is presented in Equation (10):

In Equation (10), represents the scale parameter.

The Lévy mechanism is a mechanism in random search algorithms, mainly used to simulate the distribution of random step sizes to improve the global search ability and local solution accuracy of the algorithm. The core of the Lévy mechanism lies in its step size distribution following the Lévy distribution, which has heavy tailed characteristics, meaning that most of the steps are small, but occasionally there may be extremely large steps. This feature enables the Lévy mechanism to balance global and local search during the search process, allowing exploration in a vast search space while delving deeper into specific areas. Equation (8) establishes three update strategies for nest positions, which are based on the interactions among different populations: the entire population (N1), the current best nest (N2), and the current individual nest (N3). Interaction information derived from these populations is used to update the nest positions and calculate the fitness value of the current nest. The method for updating the nest position is then randomly selected. Interaction information greatly influences the random nest, and to ensure the interaction information is comprehensive, a Cauchy operator is introduced. The Cauchy operator is used to perturb the selection of the nest update position owing to its ability to traverse all individuals in the population without repetition. This method enables the effective collection of comprehensive information from the entire population.

In Update Strategy 1, the interaction information is constructed according to the difference between two randomly selected nests within the population, N1 and N1. This approach reflects global optimization across the entire population (N1 and N1). In Update Strategy 2, the interaction information is based on the fitness difference between N1 and N2, and the nest position is updated along the dimension defined by N1 and N2. In Update Strategy 3, interaction information is generated between N1 and N3 owing to the differences between them. By incorporating interaction information among N1, N2, and N3, this strategy effectively mitigates the singularity and one-sidedness of iterative nest information. This approach broadens the search field and enhances the algorithm’s optimization capability, enabling the dynamic seeking of the optimal solution and overcoming the limitations of static optimization methods.

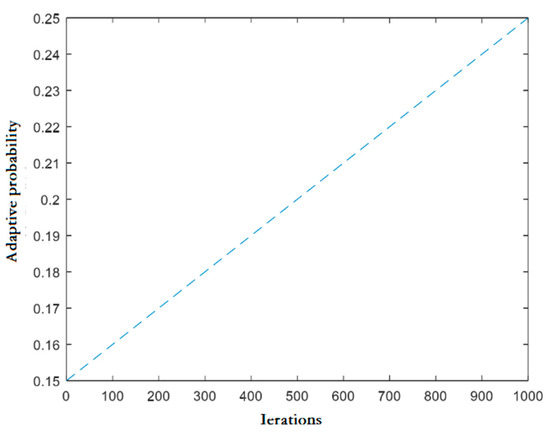

4.3. Adaptive Switching Discovery Probabilistic Strategy

In conventional cuckoo search methodologies, the discovery probability is statically set at 0.25. This static value lacks adaptability and can reduce diversity by discarding too many nests during iterations, thereby limiting the algorithm’s problem-solving capability. To address the limitations of traditional approaches, this study introduces an adaptive dynamic enhancement to the discovery probability. The fixed discovery probability is replaced by an adaptively adjusted discovery probability, formulated as follows:

In this context, , represents the current iteration number within the algorithmic process, and refers to the maximum number of iterations defined for the algorithm. The adaptively adjusted discovery probability is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Adaptive switching discovery probability chart.

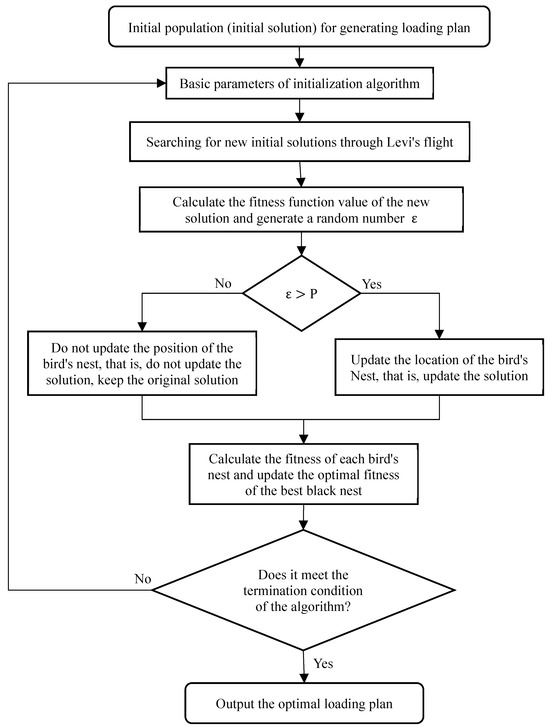

This paper addresses the container terminal stowage problem using an ICS algorithm. The constraints of the container terminal stowage problem are detailed, and an optimization mathematical model is developed to minimize container rehandling operations. The ICS algorithm first generates an initial stowage plan using a heuristic rule. The algorithm considers relevant loading rules and ship constraints to solve the container terminal stowage problem. When the algorithm reaches the termination conditions, it outputs the final results of the iteration. The detailed procedure for solving the container terminal stowage problem using the ICS algorithm is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the algorithm for solving the container stowage problem.

5. Numerical Experiments

5.1. Input Data Generation

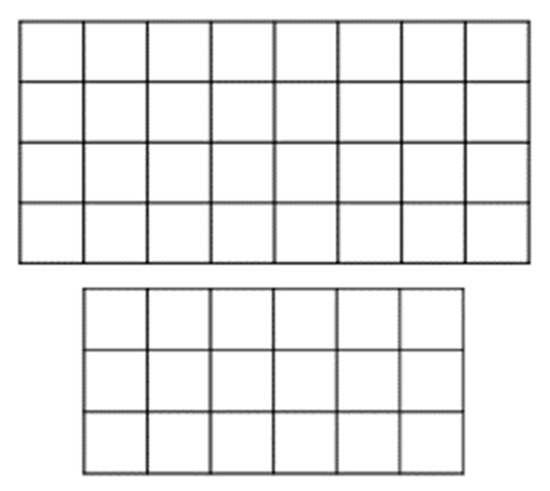

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm for optimizing automated container terminal stowage, this section presents comparative experiments between the particle swarm optimization (PSO) and ICS algorithms. By conducting on-site research on the fourth-phase terminal of Nansha Port Area in Guangzhou Port, a calculation example was generated based on actual data, as shown in Table 2. Six sets of test cases, varying in scale, are selected according to the results of the yard slot allocation. For these cases, the container weight distribution in the yard is as follows: Heavy containers (16 t to 20 t) account for 50% of the total, medium-weight containers (11 t to 15 t) account for 30%, and light containers (5 t to 10 t) account for 20%. The structure of the container ship bays awaiting loading is illustrated in Figure 4. The scales of the test cases are varied through the adjustment of the number of layers and columns in the ship bays. The experimental data for the six test cases are provided in Table 2. The parameters for the algorithms are set as follows: The population size for the ICS algorithm is 100, with a maximum number of iterations , and the parameter . In the PSO algorithm, the learning factors are set to , the inertia weight decreases linearly from 0.9 to 0.4 as the number of iterations increases, and the particle population is also set to 100. All algorithms in this article are coded using the MATLAB R2015b software. The software runs on an Intel (R) Core (TM) i7 2.70 GHz processor, 4GB of memory, and a Windows 10 (64 bit) laptop operating system.

Table 2.

Basic data table for test cases.

Figure 4.

Structural diagram of container ship bays.

5.2. Evaluation of the Candidate Solution Approaches

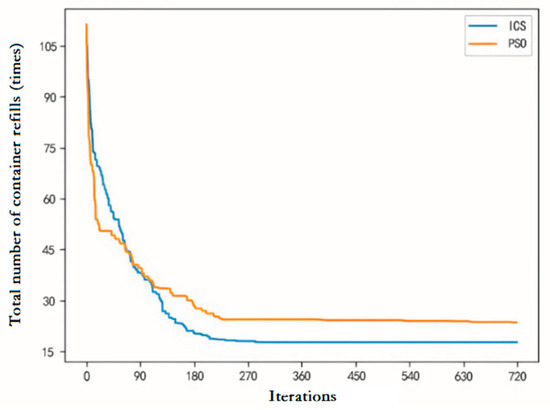

The operational results of the ICS and PSO, GA, ACO (ant colony optimization), and HS (harmony search) algorithms are presented in Table 3, where represents the maximum list moment of the ship bays () over 20 runs, represents the average solution time (s), and is the maximum allowable list moment value (). Additionally, Test Case P6 is selected to compare the convergence performances of the ICS and PSO algorithms. The selection curves for the optimal fitness values from 30 runs are shown in Figure 5.

Table 3.

Test case results table.

Figure 5.

Iteration curve comparison for Test Case 6.

From the comparison of various data in Table 3, it can be seen that the algorithm proposed in this paper is superior to the other compared algorithms. Figure 5 compares the convergence curves of the ICS and PSO algorithms for Test Case P6. The convergence analysis reveals that the ICS algorithm achieves superior results. The iteration curve for the ICS algorithm indicates that it reaches the optimal value after approximately 250 iterations, with a smooth and stable convergence trajectory. In contrast, the PSO algorithm, although tending towards the optimal value after around 300 iterations, exhibits an unstable iteration curve and converges to a less favorable optimal value than the ICS algorithm. These results suggest that the ICS algorithm offers stronger convergence performance and greater stability than the PSO algorithm. From the advantages of the algorithm proposed based on mathematical optimization models in this article, it can be seen that the model has certain applicability and can provide decision-making references for ports.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigates the stowage of automated container terminals. The findings reflect real-world scenarios to some extent and can help alleviate the operational pressure on docks. The research considered the impact of the yard container retrieval sequence and the stowage results within ship bays on the rate of container rehandling. Experimental trials validated the proposed mathematical model and optimization algorithm, which outperformed the PSO algorithm. The relationship between the objective function value and the number of iterations was also established. The results prove that the proposed algorithm can effectively address real-world stowage decision-making problems at container terminals and enhance dock loading efficiency.

This article studies the container loading plan of automated container terminals, but there are still directions for further research: (1) Integration with other systems (such as railways or trailers) for unloading and loading can be explored. (2) In terms of methodology, the algorithm proposed in this article is more commonly applied to continuous problems and less commonly used for discrete optimization problems, which can lead to adaptability issues. Therefore, in the future, hybrid heuristic algorithms can be designed in combination with discrete algorithms for optimization. (3) Artificial intelligence technology can be combined to increase the efficiency of algorithms. (4) A directly solvable model needs to be established for the original research content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H., Y.W. and P.Z.; Methodology, P.H. and Y.W.; Software, P.H. and Y.W.; Validation, P.H.; Formal analysis, P.H.; Writing—original draft, P.H. and Y.W.; Writing—review & editing, P.H. and P.Z.; Supervision, P.H. and P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a project granted by National Social Science Fund of China (22AZD108).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gao, Y.; Zhen, L. A decision framework for decomposed stowage planning for containers. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 183, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Fan, H.; Fan, H. Blocks allocation and handling equipment scheduling in automatic container terminals. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 153, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, X.; Xu, Z.; He, L.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y. Automated rail-water intermodal transport container terminal handling equipment cooperative scheduling based on bidirectional hybrid flow-shop scheduling problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 186, 109696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, D.; Gheith, M.; Eltawil, A. A comprehensive review and directions for future research on the integrated scheduling of quay cranes and automated guided vehicles and yard cranes in automated container terminals. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 179, 109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, Q.; Pan, L. Advancing multi-port container stowage efficiency: A novel DQN-LNS algorithmic solution. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 299, 112074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, C. Ship allocation optimisation centred on automated terminals. Comput. Appl. 2021, 41, 3385–3393. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Jian, Z. Modelling and implementation of an intelligent stowage simulator for container ships. Int. J. Simul. Process Model. 2020, 15, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avriel, M.; Penn, M.; Shpirer, N. Container ship stowage problem: Complexity and connection to the coloring of circle graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2000, 103, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, J. Container yard export box stacking model and its algorithm. Logist. Technol. 2007, 30, 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Park, K.T. A note on a dynamic space-allocation method for outbound containers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2003, 148, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Wan, Y.W.; Murty, K.G.; Linn, R.J. Storage space allocation in container terminals. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2003, 37, 883–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzazi, M.; Safaei, N.; Javadian, N. A genetic algorithm to solve the storage space allocation problem in a container terminal. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 56, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserta, M.; Schwarze, S.; Voß, S. A mathematical formulation and complexity considerations for the blocks relocation problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 219, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Yard storage planning for minimizing handling time of export containers. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2015, 27, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petering, M.E.H. Real-time container storage location assignment at an RTG-based seaport container transshipment terminal: Problem description, control system, simulation model, and penalty scheme experimentation. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2015, 27, 351–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.S.D. Aloading Model for a Container Ship; Cambridge Navigation: Matson, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Aslidis, A. Optimal Container Loading; MIT: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino, D.; Paolucci, M.; Sciomachen, A. A MIP Heuristic for Multi Port Stowage Planning. Transp. Res. Procedia 2015, 10, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H. Evaluation of the number of rehandles in container yards. Comput. Ind. Eng. 1997, 32, 701–711. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J. How to reduce two times overturning in container box area. Containerisation 2002, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovsky, O.; Levitin, G.; Penn, M. A Genetic Algorithm with a Compact Solution Encoding for the Container Ship Stowage Problem. J. Heuristics 2002, 8, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, D.; Sciomachen, A.; Tanfani, E. Stowing a containership: The master bay plan problem. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2004, 38, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, A.; Etsuko, N. The containership loading problem. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 2002, 4, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, K.; Pacino, D.; Jensen, R.M. On the complexity of container stowage planning problems. Discret. Appl. Math. 2014, 169, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Bostel, N.; Dejax, P.; Cai, J.; Xi, L. A tabu search algorithm for the integrated scheduling problem of container handling systems in a maritime terminal. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 181, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bai, J.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, S. A new secondary decomposition-ensemble approach with cuckoo search optimization for air cargo forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 90, 106161. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Guo, X.; Tang, H.; Wu, R.; Liu, J. An improved cuckoo search algorithm for the hybrid flow-shop scheduling problem in sand casting enterprises considering batch processing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 108921. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, H.L.; Sang-To, T.; Wahab, M.A.; Cuong-Le, T. Structural damage identification in thin-shell structures using a new technique combining finite element model updating and improved Cuckoo search algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2022, 173, 103206. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).