Abstract

BCube is one of the main data center networks because it has many attractive features. In practical applications, the failure of components or physical connections is inevitable. In data center networks in particular, switch failures are unavoidable. Fault-tolerance capability is one main aspect to measure the performance of data center networks. Connectivity, fault tolerance Hamiltonian connectivity, and fault tolerance Hamiltonicity are important parameters that assess the fault tolerance of networks. In general, the distribution of fault elements is scattered, and it is necessary to consider the distribution of fault elements in different dimensions. We research the fault tolerance of BCube when considering faulty switches and faulty links/edges that distribute in different dimensions. We also investigate the connectivity, fault tolerance Hamiltonian connectivity, and Hamiltonicity. This study better evaluates the fault-tolerant performance of data center networks.

MSC:

05C85; 68W15

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of network resources and data, cloud computing has risen rapidly in the field of computer applications [1,2]. The purpose of cloud computing is to reduce the computing task burden of end users and complete the majority of computing in the cloud by large data center networks. Data center networks are infrastructures of cloud computing and innovation platforms of next-generation networks. Data center network research has become a popular aspect in academia and industry. Scholars have proposed many data center networks, for example, Fat-Tree [3], DCell [4,5,6], BCube [7,8], VL2 [9], CamCube [10], Ficonn [11], FSquare [12], BCDC [13,14], and so on. Because of its desirable features, such as symmetry, small diameter, high fault tolerance, and so on, BCube has become a main data center network. It supports one-to-one and one-to-several traffic patterns [15]. It has good communication performances because it can build serveral vertex disjoint paths of shorter lengths [16]. The embedding of the path or the cycle is one of the main research topics in networks because many effective algorithms for solving various graph problems have been developed on the basis of paths and cycles [17,18,19,20] and some parallel applications [21,22]. Hamiltonian path and Hamiltonian cycle embeddings are important properties because the occurrence of congestion and deadlock can be effectively reduced or even avoided by multi-cast algorithms based on Hamiltonian paths and Hamiltonian cycles [23]. Consequently, there are a great number of research findings on Hamiltonian properties on particular network topologies, such as hypercube [24], cross cube [25,26], twist cube [27,28,29], extended cube [30], k-ary n-cube [31,32,33], and DCell [34,35].

In practical applications, the failure of components or physical connections in data center networks is inevitable. Fault tolerance is a vital aspect to measure the performance of networks [36,37]. Edge connectivity is the main feature used to assess the fault tolerance of networks, which is often exactly equivalent to a network’s minimum degree. and the set of faulty edges that make it disconnected is often connected to a node whose degree is exactly equivalent to this network’s minimum degree. In general, that all the faulty edges are concentrated on the adjacent edges of a certain node is almost impossible. Harary [38] proposed the concept of edge connectivity under some conditions in 1983. There are several related studies on this topic, such as conditional edge connectivity [39,40], extra edge connectivity [41,42], and component edge connectivity [43]. In practical applications, the distribution of fault elements may be scattered. The fault elements may be distributed in different dimensions in networks. It is necessary to study the fault situation in terms of dimensions. It is inevitable that switches in data center networks will fail. If a switch is faulty, the servers connecting to it are disconnected from each other. Faulty switches will have a more destructive effect on the stability of the networks. So, we research the fault tolerance of BCube when considering faulty switches and faulty links/edges that distribute in different dimensions.

A data center network can be denoted with a graph, where nodes are servers, edges are links connecting servers, and switches can be considered transparent devices. The topological properties of data center networks are critical to data center performance. is a k-dimensional BCube that is constructed with n-port switches, where and [7]. The graph can be viewed as the topological structure of , where switches are considered to be transparent [44]. In this paper, we give the corresponding relation between and and research the connectivity, fault-tolerant Hamiltonian connectivity, and Hamiltonicity of when the faulty elements distribute in different dimensions.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we begin by introducing some notations. Next, we give the definitions and properties of and . We also show the corresponding relations between and .

The graph-theoretical terminologies and notations mainly follow [45]. Given an undirected simple graph , denotes the node set, and represents the edge set. For any node u in G, let be the set of its neighbors. The degree of u, marked as , is the number of neighbors of u. A path is a sequence of neighboring nodes in which all nodes are different except possibly . If a path travels through each node of G precisely once, it is called a Hamiltonian path. A path that starts and finishes at the same node is said to be a cycle. A cycle containing all of G’s nodes is known as a Hamiltonian cycle. If G has a Hamiltonian cycle, G is Hamiltonian. If there is a Hamiltonian path linking any two different nodes in G, then G is said to be Hamiltonian-connected. For , let , , ⋯, be n disjoint graphs. The union of , represented by , is the graph with the node set and the edge set for any two positive integers i and j with . The graph is isomorphic to the graph if there exists a bijection : such that if and only if , represented by . is used to represent the integer set for any two positive integers i and j with .

The BCube can be recursively defined, which contains three types of elements, namely switches, servers, and links. Multi-port servers are connected to switches with a fixed number of ports by links. For any integers and , a server y of can be denoted by . Each switch in can be represented by , where l is the level(or dimension) of the switch and . A link is represented by . Each server with ports is linked to one switch at every level. These levels are recorded from Level 0 to Level k. Obviously, there exist switch levels and servers in . Each level has switches. Following [7], we define recursively.

Definition 1

([7]). The definition of is as below.

(1) For , contains one switch with an n-port and n servers, which are connected to the switch.

(2) For , contains switches with an n-port and n disjoint copies of , where:

α For every , we obtain the subgraph by prefixing the label of every server with j in one copy of ;

β For any , a server is connected to the switch if and only if , where j denotes the j-th port of the switch to which the server is connected to.

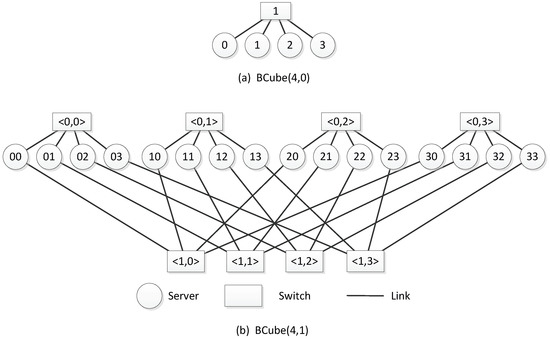

has four servers and one four-port switch (see Figure 1). contains four disjoint copies of , which are connected by four four-port Level 1 switches (see Figure 1). Each server has two ports in .

Figure 1.

and .

By making all switches transparent, we can obtain the topological structure of BCube. The topological structure of is represented by , which is defined as follows.

Definition 2.

Given two integers k, n, and , is represented by a simple undirect graph ,, where and . For any two nodes and , if and only if there exists an integer such that and for all . We say is an i-dimensional edge, denoted by i-edge. We set being the set of all i edges of .

A graph can be decomposed into n disjoint subgraphs: , , …, along dimension k, where , for every , is a subgraph of induced by . Any two subgraphs are connected by the k-edges, which correspond to the Level k switches in . Clearly, each is isomorphic to for . The subgraph of , , is also the topological structure of the subgraph of making switches transparent. Along k different dimensions, can be decomposed into n copies of .

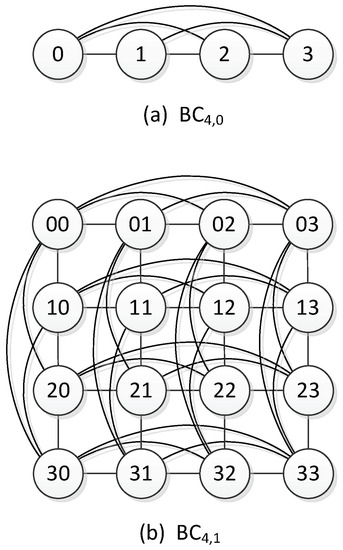

and are shown in Figure 2. is a kind of generalized hypercube. The graph is isomorphic to the hypercube . For any node y in , the degree of y is . is a highly symmetric network with vertex symmetry and edge symmetry.

Figure 2.

and .

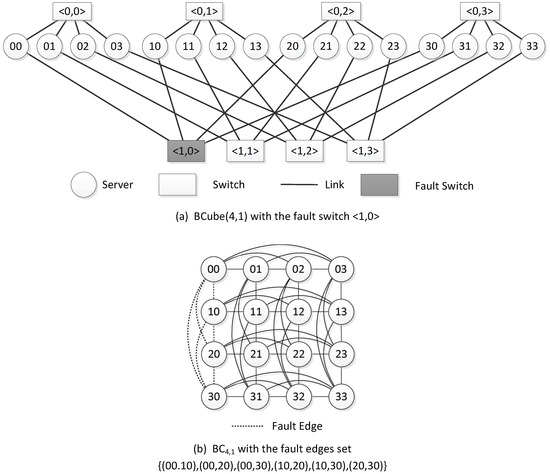

The corresponding relation between the elements in and the elements in will be discussed below. Let z be one of the elements in . If the element z is a server, it corresponds to a node in . If the element z is a switch, it corresponds to an edge subset and y are two distinct nodes, which correspond to two distinct servers of connected by the switch If the element z is a link, it corresponds to an edge subset and v are two distinct nodes, which correspond to two servers of connected through the link z}. Given an integer l, , if the element z is a switch of in Level l, it corresponds to the edge subset of , which has edges. As shown in Figure 3, the corresponding element of the fault switch in is the edge subset in .

Figure 3.

with the fault switch and with the fault edges set.

We let be a set, each element of which is a faulty edge subset in , which is affected by a broken switch in . And let be the set, each element of which is a faulty edge subset in , which is caused by a broken switch of in Level i, with . Clearly, . Let be the set of the faulty edges in which is not caused by faulty switches. Let u and v be two servers in . If a faulty edge exists, the server u is unable to communicate with the server v. Furthermore, let be the set of the i-edges in the faulty edge set , . We let , , , , , , , , . Because is able to reflect the characteristics of , we will carry out the below study on .

3. Fault-Tolerant Properties of

Considering that is edge symmetric and node symmetric, we assume . For , we set for each and for each . Note that the subgraph of induced by is isomorphic to . The graph is isomorphic to the -dimensional hypercube . The relevant conclusions have been drawn and will be presented in another paper. So, we discuss the properties of for in this paper.

Theorem 1.

For any faulty set F of , , is connected if and for each .

Proof.

The proof of this theorem is by induction on k. Obviously, is connected if . Suppose that this theorem holds on , where and . Since is edge symmetric, we assume that . Then, . For , let be the set, each element of which is a faulty edge subset in , which is caused by a faulty switch in in Level i with . . Let be the edge subset of the faulty i-edges in . . Let , , . Since , for each j. Hence, , for each ; that is, . , . By induction hypothesis, is connected for each . Since , there is an edge e between and such that for each . Hence, is connected. □

We use the following example to show that the bound is tight.

Example 1.

Let us consider that for some with fixed t. We discuss two cases.

Case 1. . We set and assume that all the switches are faulty, which are connected with the node u and . Obviously, , for . Then, is disconnected since and one component of is the node u.

Case 2. . Let B be the connected subgraph of which is induced by . Obviously, B is isomorphic to . Then, we have for each , and for each . We set . We have (1) , (2) , and (3) for each . Then, is not connected and one component of it is the subgraph B.

Theorem 2

([46]). For , let with and . Let be the set of faulty elements in . For any two nodes and , there is a fault-free Hamiltonian path in where (1) For any integer , is Hamiltonian-connected. (2) There exist at least three fault-free k-edges between any two distinct graphs in the subgraph set A.

Theorem 3.

For , let F be any faulty set of , , is Hamiltonian-connected if and .

Proof.

is Hamiltonian-connected if and . So, we discuss the case .

can be divided into n subgraphs for . For each , is Hamiltonian-connected because it is a complete graph with n nodes. Since , there is no fault element in , . Since , there are at least three fault-free switches in Level 1 in . We consider any three fault-free switches. We assume these switches individually connect with the nodes , and , for . For any two nodes , , , we divide into two cases to discuss the existence of a Hamiltonian path connecting the nodes u and v in .

Case 1. .

By Theorem 2, there exists a fault-free Hamiltonian path connecting u and v in .

Case 2. .

W.L.O.G., we suppose . We have two subcases.

Case 2.1. .

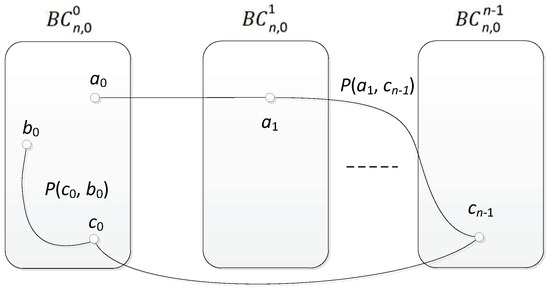

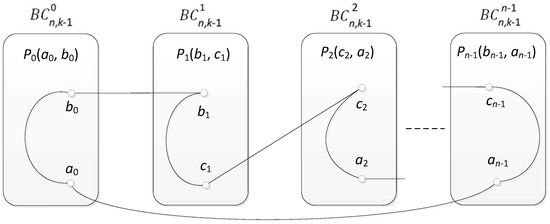

We assume that . Since is a complete graph, there is an edge and a path , which contains all the nodes in . By Theorem 2, a fault-free Hamiltonian path exists, which connects and in . So, ,, , , , , , is a fault-free Hamiltonian path connecting u and v in (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The illustration for Case 2.1 of Theorem 3.

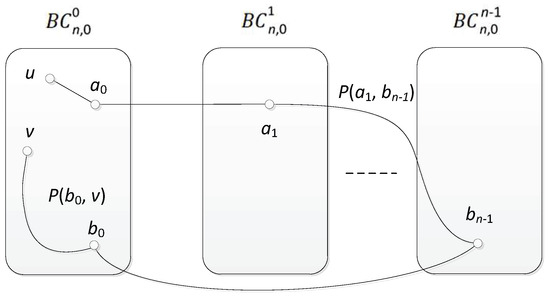

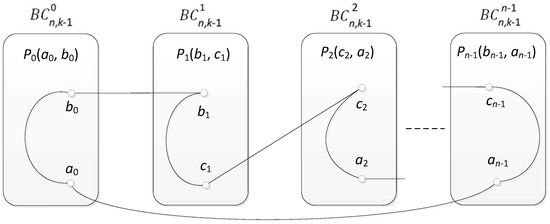

Case 2.2. .

We assume that , . Since is a complete graph, is also a complete graph. In , there is a Hamiltonian path connecting and . By Theorem 2, a Hamiltonian path exists, which connects and in . So, is a Hamiltonian path connecting u and v in . So, is Hamiltonian-connected if and (see Figure 5). □

Figure 5.

The illustration for Case 2.2 of Theorem 3.

Theorem 4.

For and , let F be any faulty set of , , is Hamiltonian-connected if for each and , .

Proof.

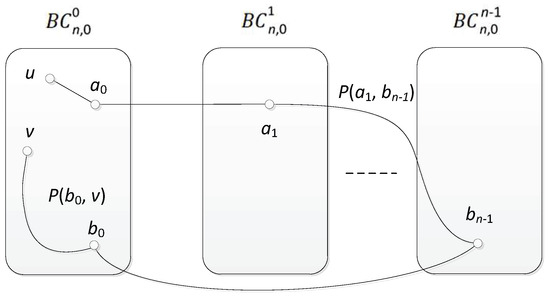

The proof of this theorem is by induction on k. By Theorem 3, is Hamiltonian-connected if and . Assume that this theorem holds on with , .

For , let be the set, each element of which is a faulty edge set in , which is caused by a faulty switch in in Level i with . . Let be the edge subset of the faulty i-edges in . . . Since , for each . Hence, for , and , . By induction hypothesis, is Hamiltonian-connected for each . Since , there are more than three fault-free edges between and for in . By Theorem 2, for any two nodes , , and , a Hamiltonian path exists, which connects u and v in .

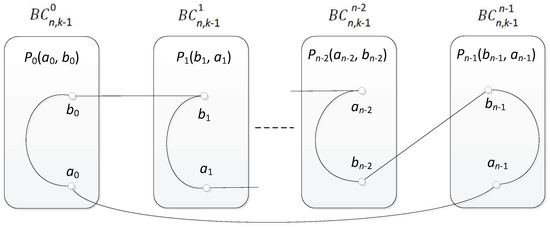

Here, we consider the situation . W.L.O.G., we suppose . So, . In , there is a Hamiltonian path of length . Since , there exists an edge on the Hamiltonian path such that the two Level k switches are fault-free in , which connect with the nodes u and v individually. Let . Let be the node that connects to the same Level k switch with the node . Let be the node that connects to the same Level k switch with the node . By Theorem 2, a Hamiltonian path exists, which connects and in . Then, , , , , is a fault-free Hamiltonian path connecting u and v in . So, is Hamiltonian-connected if for each and , . □

Theorem 5.

For and n mod , , let F be any faulty set of , , is Hamiltonian if for each and , , .

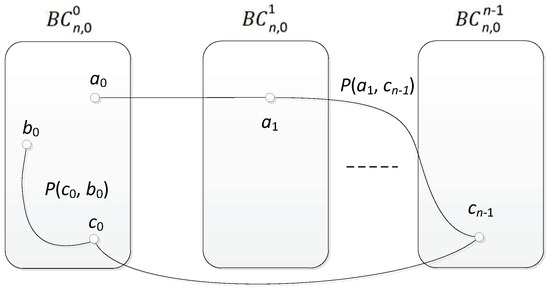

Proof.

By Theorem 4, is Hamiltonian-connected for each . Since , there are at least two fault-free switches in Level k in . So, we assume that one switch connects with the nodes , and the other connects with the nodes , , . By Theorem 4, is Hamiltonian-connected for each . So, there is a Hamiltonian path or between and in . Since n is even, the cycle is a Hamiltonian cycle in . So, is Hamiltonian for and n mod , as shown in Figure 6. □

Figure 6.

The illustration of Theorem 5.

Note that there is no Hamiltonian cycles in for if n is odd. We have the theorem below for odd number n.

Theorem 6.

For and n mod , , let F be any faulty set F of , , is Hamiltonian if for each and , , .

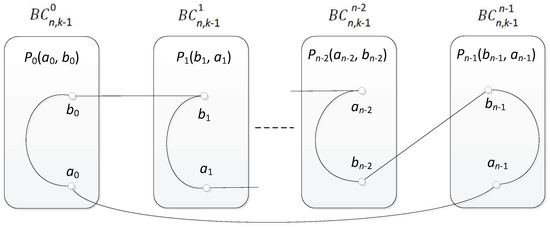

Proof.

By Theorem 4, is Hamiltonian-connected for each . Since , there are at least three fault-free switches in Level k in . So, we assume that one switch connects with the nodes , one switch connects with the nodes , and the other connects with the nodes , , . By Theorem 4, is Hamiltonian-connected for each .

So, there is a Hamiltonian path , or between any two nodes of in . Since n is odd, the cycle , , , , , , , , …, , , is a Hamiltonian cycle in . So, is Hamiltonian for and n mod if for each and , , , as shown in Figure 7. □

Figure 7.

The illustration of Theorem 6.

4. Performance Analysis

Up to now, we have shown is connected when faulty switches and faulty links distributing in different dimensions are considered. In this section, we are going to demonstrate the superiority of our results from two aspects. Compared with link faults, switch faults are more destructive, so we assume that all the fault elements are switches when analyzing performance. We discuss the maximum number of faulty switches that the network can tolerate while maintaining connectivity. We also investigate the maximum distance between any two nodes in when the number of faulty elements reaches the maximum.

4.1. Number of Faulty Switches

According to the proof, the maximum number of faulty switches that can tolerate is when is still connected. We list the maximum number of faulty switches for and that can tolerate in Table 1. These results indicate that still has good properties while there are more faulty elements compared with the traditional method.

Table 1.

Maximum Number of Faulty Switches that Can Tolerate When is still Connected.

4.2. The Average Value of The Maximum Distance between Any Two Nodes

In this subsection, we investigate the maximum distance between any two nodes in when switches become faulty in . The fault switches are distributed in different levels of and each level i has faulty switches where . We design an algorithm to calculate the maximum distance between any two nodes in . The faulty switches are distributed randomly in . We repeat the algorithm 100 times to obtain the average value of the maximum distance between any two nodes in .

has switch levels where there exist n-port switches in each level. To remove a switch s of level i, we need to disconnect all the servers adjacent to s. If two servers and are connected to the same switch of level i, they are connected by an i-dimensional edge, and is an i-dimensional neighbor of . We use to denote the i-dimensional neighbor set of in . In , the switches are transparent. To randomly remove a switch of level i, we can randomly select a node , then remove all the i-dimensional edges between any two nodes in . Please see Algorithm 1 for an illustration. The results obtained from Algorithm 2 are shown in Table 2. These results indicate that the distance between any two nodes is still small in while there are more faulty elements.

| Algorithm 1 removeSwitches(g,n,k) |

Input: g: a k-dimensional ; n: the port number of a switch in the BCube; k: the dimension of the BCube;

|

Table 2.

The average value of the maximum distance between any two nodes.

| Algorithm 2 AverageMaxDistance() |

| Input: n: the port number of a switch in the BCube; k: the dimension of the BCube; Output: the average value of the maximum distance between any two nodes in ;

|

5. Conclusions

In this work, we investigate the fault tolerance of BCube while faulty links and faulty switches distribute in different dimensions. We reveal the properties of BCube in its topological graph for and . This paper shows that (1) is connected if and for each ; (2) is Hamiltonian if for each and , , ; (3) If n mod , is Hamiltonian if for each and , , ; (4) If n mod , is Hamiltonian if for each and , , . These results indicate that compared with the traditional method, BCube still has good properties while there are more faulty elements. Based on the results obtained here, we will consider several properties such as fault tolerant routing, diameter of BCube as future research directions. In addition, our results can be extended to other data center networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, L.Y.; investigation, C.-K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and C.-K.L.; writing—review and editing, L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Shin Kong Wu Ho Su Memorial Hospital National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University Joint Research Program (No. 111-SKH-NYCU-03), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61902113), the Doctoral Research Foundation of Henan University of Chinese Medicine (No. BSJJ2022-14) and the Research Project of Suzhou Industrial Park Institute of Services Outsourcing (No. SISO-ZD202202).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khan, A.; Uthansakul, P.; Duangmanee, P.; Uthansakul, M. Energy efficient design of massive MIMO by considering the effects of nonlinear amplifiers. Energies 2018, 11, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthansakul, P.; Anchuen, P.; Uthansakul, M.; Khan, A. Qoe-aware self-tuning of service priority factor for resource allocation optimization in LTE networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 69, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.; Alexander, L.; Amin, V. A scalable, commodity data center network architecture. In ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Wu, H.; Tan, K.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, S. DCell: A scalable and fault-tolerant network structure for data centers. In SIGCOMM ’08, Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2008 Conference on Data Communication, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–22 August 2008; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kliegl, M.; Lee, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, C.; Rincón, D. Generalized dcell structure for load-balanced data center networks. In Proceedings of the 2010 INFOCOM IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops, San Diego, CA, USA, 15–19 March 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Lin, C.-K.; Jia, X. Vertex-disjoint paths in dcell networks. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2016, 96, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Lu, G.; Li, D.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Tian, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, S. BCube: A high performance, server-centric network architecture for modular data centers. In SIGCOMM ’09, Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2009 Conference on Data Communication, Barcelona, Spain, 16–21 August 2009; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.; Liu, Y.; Hamdi, M.; Muppala, J.K. Hyper-BCube: A scalable data center network. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 10–15 June 2012; pp. 2918–2923. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, A.; Hamilton, J.R.; Jain, N.; Kandula, S.; Kim, C.; Lahiri, P.; Maltz, D.A.; Patel, P.; Sengupta, S. Vl2: A scalable and flexible data center network. In SIGCOMM ’09, Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2009 Conference on Data communication, Barcelona, Spain, 16–21 August 2009; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Libdeh, H.; Costa, P.; Rowstron, A.; O’Shea, G.; Donnelly, A. Symbiotic routing in future data centers. In SIGCOMM ’10, Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2010 Conference, New Delhi, India, 30 August–3 September 2010; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Guo, C.; Wu, H.; Tan, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, S. FiConn: Using backup port for server interconnection in data centers. In Proceedings of the INFOCOM 2009, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 19–25 April 2009; pp. 2276–2285. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, F. Dual-centric data center network architectures. In Proceedings of the 2015 44th International Conference on Parallel Processing, Beijing, China, 1–4 September 2015; pp. 679–688. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, M.; Cheng, B.; Fan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Yu, J. The conditional reliability evaluation of data center network bcdc. Comput. J. 2021, 64, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Lin, C.-K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Z. Bcdc: A high-performance, server-centric data center network. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2018, 33, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Li, X.; Chang, J.-M.; Jia, X. Constructing multiple CISTs on BCube-based data center networks in the ccurrence of switch failures. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2023, 72, 1971–1984. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Lin, W.; Guo, W.; Chang, J.-M. A secure data transmission scheme based on multi-protection routing in datacenter networks. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2022, 167, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Xu, L.; Huang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; He, X. On exploiting priority relation graph for reliable multi-path communication in mobile social networks. Inf. Sci. 2019, 477, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zhou, S.; Sun, X.; Lian, G.; Liu, J. Reliability of (n,k)-star network based on g-extra conditional fault. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2019, 757, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Fan, J.; Jia, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X. Hamiltonian properties of honeycomb meshes. Inf. Sci. 2013, 240, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Yang, W.; Zhang, S. Number of proper paths in edge-colored hypercubes. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 332, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, B.; Ma, M.; Xu, J. Many-to-many disjoint paths in hypercubes with faulty vertices. Discret. Appl. Math. 2017, 217, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, E.; Meng, J. Parallel routing in regular networks with faults. Inf. Process. Lett. 2019, 142, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; McKinley, P.; Ni, L. Deadlock-free multicast wormhole routing in 2d mesh multicomputers. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 1994, 5, 783–804. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Tan, J.J.; Liang, T.; Hsu, L.-H. Fault-tolerant hamiltonian laceability of hypercubes. Inf. Process. Lett. 2002, 83, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-S.; Fu, J.-S.; Chen, G.-H. Fault-free hamiltonian cycles in crossed cubes with conditional link faults. Inf. Sci. 2007, 177, 5664–5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Hamiltonian embedding in crossed cubes with failed links. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2012, 23, 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Jia, X.; Lin, X. Embedding of cycles in twisted cubes with edge-pancyclic. Algorithmica 2008, 51, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, R.-W. Embedding two edge-disjoint hamiltonian cycles into locally twisted cubes. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2011, 412, 4747–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.-L. Geodesic pancyclicity of twisted cubes. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181, 5321–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.-Y.; Cian, Y.-R. Conditional edge-fault hamiltonicity of augmented cubes. Inf. Sci. 2010, 180, 2596–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Lin, C.-K.; Fan, J. Hamiltonian cycle and path embeddings in k-ary n-cubes based on structure faults. Comput. J. 2017, 60, 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Lin, C.-K.; Fan, J.; Jia, X. Hamiltonian cycle and path embeddings in 3-ary n-cubes based on k1,3-structure faults. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2018, 120, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Li, X.; Chang, J.-M.; Wang, D. An efficient algorithm for hamiltonian path embedding of k-ary n-cubes under the partitioned edge fault model. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2023, 34, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Hao, R. Conditional edge-fault-tolerant hamiltonicity of the data center network. Discret. Appl. Math. 2018, 247, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Erickson, A.; Fan, J.; Jia, X. Hamiltonian properties of dcell networks. Comput. J. 2015, 58, 2944–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J.; Lin, C.-K. The restricted h-connectivity of the data center network dcell. Discret. Appl. Math. 2016, 203, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xu, J. Conditional fault tolerance of arrangement graphs. Inf. Process. Lett. 2011, 111, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harary, F. Conditional connecticity. Networks 1983, 13, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Tan, J.J. Restricted connectivity for three families of interconnection networks. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 188, 1848–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Guo, X. Fault tolerance of hypercubes and folded hypercubes. J. Supercomput. 2014, 68, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Hao, R.; Cheng, E. Note on applications of linearly many faults. Comput. J. 2020, 63, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhai, S.; Xu, L. Relation of extra edge connectivity and component edge connectivity for regular networks. Int. J. Found. Comput. Sci. 2021, 32, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Gu, M.; Chang, J. Relationship between extra edge connectivity and component edge connectivity for regular graphs. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2020, 833, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fan, J.; Lin, C.-K.; Jia, X. Diagnosability evaluation of the data center network dcell. Comput. J. 2017, 6, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-H.; Lin, C.-K. Graph Theory and Interconnection Networks; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Lin, C.-K.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, B. Fault-tolerant hamiltonicity and hamiltonian connectivity of bcube with various faulty elements. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2020, 35, 1064–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).