Abstract

Software defect prediction (SDP) methodology could enhance software’s reliability through predicting any suspicious defects in its source code. However, developing defect prediction models is a difficult task, as has been demonstrated recently. Several research techniques have been proposed over time to predict source code defects. However, most of the previous studies focus on conventional feature extraction and modeling. Such traditional methodologies often fail to find the contextual information of the source code files, which is necessary for building reliable prediction deep learning models. Alternatively, the semantic feature strategies of defect prediction have recently evolved and developed. Such strategies could automatically extract the contextual information from the source code files and use them to directly predict the suspicious defects. In this study, a comprehensive survey is conducted to systematically show recent software defect prediction techniques based on the source code’s key features. The most recent studies on this topic are critically reviewed through analyzing the semantic feature methods based on the source codes, the domain’s critical problems and challenges are described, and the recent and current progress in this domain are discussed. Such a comprehensive survey could enable research communities to identify the current challenges and future research directions. An in-depth literature review of 283 articles on software defect prediction and related work was performed, of which 90 are referenced.

Keywords:

software defect prediction (SDP); source code representation; deep learning; semantic key features MSC:

03-04

1. Introduction

Due to their roles in assisting developers and testers to automatically allocate the suspicious defects and prioritizing testing efforts, software defect prediction (SDP) techniques are gaining much popularity. SDP could also identify whether a software project is faulty or healthy in the early project life cycle and effectively improve the testing process and software quality [1,2]. Software is a set of instructions, programs, or data used to execute specific tasks in various applications such as cyber security [3], robotics [4,5], autonomous vehicles [6], image processing [7,8], prediction of malignant mesothelioma [9], recommendation systems [10], etc.

Previous studies have used learning techniques based on traditional metrics to build such SDP models. The specific and limited source code features have been manually generated to identify the faulty files among others such as McCabe features [11], Halstead features [12], Chidamber and Kemerer (CK) features [13], MOOD features [14], change features [15], and other object-oriented (OO) features [16]. Several machine learning techniques for SDP have been implemented, including Support Vector Machine (SVM) [17], Naive Bayes (NB) [18], Neural Network (NN) [19], Decision Tree (DT) [20], Dictionary Learning [21], and Kernel Twin Support Vector Machines (KTSVM) [22].

However, code regions with different semantics key features cannot be distinguished using existing traditional features because the traditional features could carry the same information for code regions with different semantics (see Section 4.1). Sematic feature strategies have evolved to detect suspicious defect prediction from the source codes in recent years as alternative methodologies. Rather than using the metric generator analysis, such methods could directly predict the defects from the project’s source code [23,24,25]. These approaches use recent deep learning techniques to fit the obstetric model through creating multi-dimensional features that perform perfectly in either the source code reconfiguration as a sequential structure or abstract syntax trees in the input data set. In future, advanced classification algorithms could use the semantic key features similar to the scenario of metric-based defect prediction to achieve a more effective prediction performance.

Despite the rapid advancement of the SDP domain, the preliminary survey studies [26,27,28,29,30] show insufficient reviews to capture the latest challenges of the deep learning techniques that used the source code key features for defect prediction. For example, the recent progress in the related source code analysis and representation domain was presented based on the different processing techniques such as abstract syntax trees (AST) and token, graph, or statement-based methods where they were successfully used for software defect prediction.

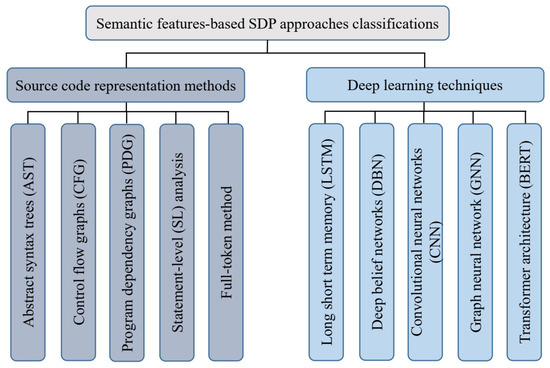

Researchers working on the field of semantic features-based SDP need to focus on two essential aspects: the representation of source code and deep learning techniques. Figure 1 shows the classifications of semantic features-based SDP approaches (See Section 4.2, Section 4.4, Section 4.5 and Section 4.6).

Figure 1.

Semantic features-based SDP approaches classifications.

In this study, a systematic literature review (SLR) strategy is conducted based on seven initial research questions (see Table 1). The main contributions of this study are:

- A comprehensive study is conducted to show the state-of-the-art software defect prediction approaches using the contextual information that is generated from the source codes. The strategies for analyzing and representing the source code is the main topic of this study.

- The current challenges and threats related to the semantic features-based SDP are evaluated through examining and addressing the current potential solutions. In addition, we provide guidelines for building an efficient deep learning model for the SDP over various conditions.

- We also group deep learning (DL) models that have recently been used for the SDP based on the semantic features collected from the source codes and compare the performance of the various DL models, and the best DL models that outperform the existing conventional ones are outlined.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the review of background and related studies, Section 3 presents the methodology of this study, Section 4 illustrates the results and answers the research questions, Section 5 summarizes the results of this study, and lastly, Section 6 presents the conclusion of this study.

2. Background and Related Studies

Section 2.1 introduces the traditional software defect prediction, Section 2.2 describes the SDP approaches based on analyzing the source code semantic features, and Section 2.3 presents the recent related studies.

2.1. Traditional Software Defect Prediction

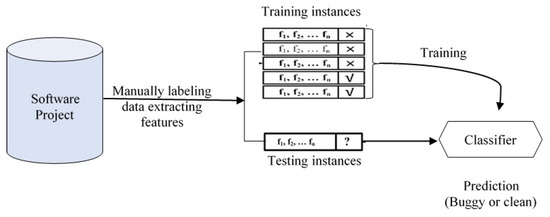

In most conventional defect prediction approaches, machine-learning-based classifiers are trained using traditional features that were manually extracted from historical defect records [24,31]. Figure 2 shows the traditional defect prediction process. The dataset must initially be classified as clean or defective depending on each file’s post-release faults. A file is considered faulty if it has coding bugs, otherwise, it is considered a clean file. The following process manually gathers the relating standard feature metrics of these records and then selects the optimal subset. Machine learning (ML) classifiers are trained using the labelled instances’ features in a supervising manner. In the end, the new instances are recognized as buggy or clean using the trained ML models.

Figure 2.

Traditional producer of the software defect prediction (SDP) in abstract view.

Previous studies presented several SDP techniques based on the standard features where Wang et al. [32] proposed a semi-boost algorithm to define the latent clustering relationship between modules expressed in an enhancing framework. Wu et al. [33] proposed dictionary learning under a semi-supervised approach using the labeled and unlabeled defect datasets. Furthermore, their method considered the classification cost errors during the dictionary learning. Zhang et al. [34] proposed an approach to generate a class balance training dataset using a Laplacian point sampling method for the labeled fault-free programs then calculated a relationship graph’s weights using a non-negative sparse algorithm. Their proposed approach predicted the identities of unlabeled software packages using a label propagation algorithm based on the constructed non-negative sparse graph. Zhu et al. [1] introduced a method for defect prediction based on a Naive Bayesian algorithm which built a training model based on the data gravity and feature dimension weight, then calculated the prior probabilities for the training data using the information weights to construct a prediction classifier for SDP. Jin [22] used the Kernel twin support vector machine (KTSVM) for performing the domain adaptation to meet various training data distributions. They used their strategy as the cross-project defect prediction (CPDP) model.

2.2. Software Defect Prediction Based on Analysis the Source Code Semantic Features

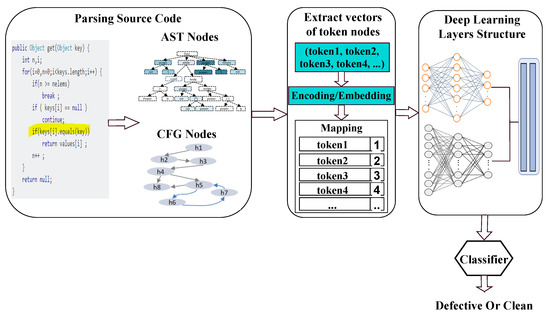

Although several traditional approaches have been presented for SDP, these traditional approaches still need to improve their prediction performance. Such SDP models based on the semantic features are currently gaining popularity in software engineering. A typical semantic feature-based SDP process is shown in Figure 3. The first step is to parse the source code and extract code nodes. There are three widely used techniques for representing the source code: Graph-based method, AST-based method, and Token-based method [35] (See Section 4.2).

Figure 3.

Software defect prediction based on source code semantic features.

The second step is to extract the token node vectors using the Encoding or Embedding process. Only the numerical vectors can be used as an input quantity for deep learning models. Thus, a unique integer identification is assigned to each token. A mapping between the different tokens and integers is created to construct the semantic features and then the token vectors are encoded/embedded into integer vectors for the deep learning models. Generally, word embedding is implemented using the global vectors (GloVe) [36] or word2vec [37] techniques. After the numeric vectors are extracted from the AST nodes, the labeling procedure is conducted automatically using the blaming function or annotating in Version Control System (VCS) [23,24,38,39]. The last step is to train the deep learning models using the labeled semantic feature dataset. After the DL model is perfectly fine-tuned, the model evaluation is performed using the testing subset to investigate the prediction performance showing weather the assessed source code module is clean or it has some defects. The most common deep learning approaches for the SDP include, but are not limited to, Convolution Neural Networks (CNN), Deep Belief Networks (DBN), Long Short Term Memory (LSTM), and Transformer Architectures (See Section 4.4 and Section 4.5).

2.3. Related Studies

First, we discuss the similar reviews and surveys on the SDP domain. Hall et al. [29] identified a review of defect prediction articles published between 2000 and 2010. Their criteria were to summarize the qualitative and quantitative results of 36 published studies to provide sufficient related information to the research community. In addition, they examined the effect of the independent variables, model context, and SDP modeling approaches, and the evaluation performances. Malhotra [40] provided a review study in the literature that used machine learning approaches for SDP from January 1991 to October 2013. They evaluated the effectiveness of the machine learning algorithms on the SDPs and also identified eight machine-learning technique categories (Bayesian learners, Decision trees, Neural networks, Ensemble learners, Rule-based learning, Support vector machines, and miscellaneous evolutionary algorithms). Their results showed the ability of machine learning to predict whether a software module is defect-prone or not. Hosseini et al. [30] summarized and synthesized existing CPDP studies to identify the performance evaluation criteria, modeling techniques, approaches, and independent variables used in CPDP model development. They conducted a comprehensive literature review with meta-analysis to achieve their study goal. Furthermore, their study aimed to examine the models of (1) CPDP achievement and (2) Within project defect prediction (WPDP).

Li et al. [41] analyzed and discussed almost 70 relevant defect prediction publications from January 2014 to April 2017. They summarized the selected papers into four aspects: effort-aware prediction, data manipulation, machine learning algorithms, and empirical studies. Rathore and Kumar [42] searched several digital libraries to find the relevant publications that were publicly published between 1993 and 2017. Li et al. [43] conducted a systematic review identifying and analyzing the studies published between 2000 and 2018. As a result, their meta-analysis showed that supervised and unsupervised models are comparable for both CPDP and WPDP models. Akimova et al. [27] presented the SDP survey based on the deep learning publications which were categorized into the defect prediction methodologies, software metrics, and data quality concerns. Taxonomic classifications of the various methods were presented for each class as well as their observations. Pandey et al. [26] reviewed different statistical approaches and machine learning research to software defect prediction from 1990 to June 2019.

Our study reviews the current state-of-the-art SDP-based deep learning approaches that used the semantic key features of the software’s source codes. Given the relatively short history of the SDP study based on the source code semantic information of programs, the first paper published on this topic was in 2016 by Wang et al. [23]. As a result, the previous reviews could not pay attention to the recent publications that focused on the source code representation and semantic information extracted from the software’s source codes. Given the practical implications mentioned above, this study systematically demonstrates the domain research gap, thus justifying our motivation to complete this study.

3. Methodology

Section 3.1 introduces the research strategy, Section 3.2 describes the research questions, and Section 3.3 presents the search for related studies.

3.1. Research Strategy

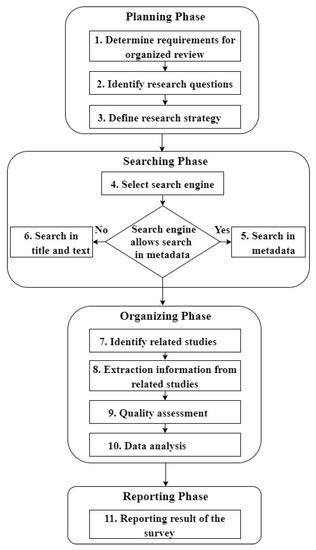

In this study, we use a strategy of SLR accomplished by the methodology proposed by [44]. Figure 4 shows the SLR steps. We define the review requirements and research questions during the planning process. We identify, select, and analyze the related studies in the searching phase. Then, the organizing phase includes extracting and analyzing information from related studies. Lastly, we report the final investigation results.

Figure 4.

Systematic literature review process.

3.2. Research Questions

The objective of this survey is to provide valuable evidence for semantic feature-based SDP using several deep learning techniques. We refined various questions regarding the SDP discipline after reviewing many relevant papers. Table 1 lists all Research Questions (RQs), seven complete RQs were framed, and some of these questions include sub-questions relating to the different SDP models. The RQ-5 comprised of one question and one sub-question, as shown in Table 1.

We also arranged standard questions to evaluate the selected studies’ validity and robustness. Table 2 shows the list of these quality assessments. The questions are graded by a score of 1 (yes), 0.5 (partial), and 0 (no). The final grade is obtained by adding the scores from each question. The maximum score per article is 10, while the minimum is 0.

Table 2.

Quality assessment questions.

Table 1.

The survey research questions.

Table 1.

The survey research questions.

| RQ-No | Research Questions |

|---|---|

| RQ-1 | What is the motivation for using semantic features in SDP? |

| RQ-2 | Which techniques are used for source code representation? |

| RQ-3 | What datasets are used in semantic features-based SDP, and where can they be obtained? |

| RQ-4 | Which deep learning techniques are used in semantic features-based SDP? |

| RQ-5 | Performance analysis of different deep learning techniques applied to semantic feature-based SDP models. |

| RQ-5.1 | Which deep learning techniques outperform existing SDP models? |

| RQ-6 | What evaluation metrics are generally used in semantic features-based SDP models? |

| RQ-7 | What are the challenges in semantic features-based SDP? |

3.3. Search for Related Studies

Searching for and selecting relevant articles is one of the essential steps of the SLR process. The boolean operators “AND” and “OR” have been applied in this step. The following terms were used: ((“deep learning” OR “deep neural network”) AND (“semantic feature” OR “contextual information”) AND “software” AND (“defect” OR “bug” OR “fault” OR “error”) AND (“prediction” OR “prone” OR “probability” OR “proneness” OR “detection” OR “identification”)). The following digital libraries and databases were selected to retrieve relevant studies:

- IEEE Xplore

- Web of Science

- Google Scholar

- Science Direct

- ACM Digital Library

- Hindawi online database

- IET Digital Library

- MDPI online database

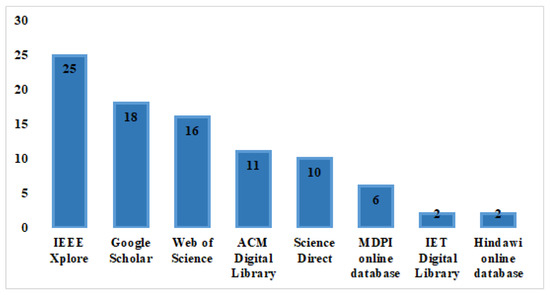

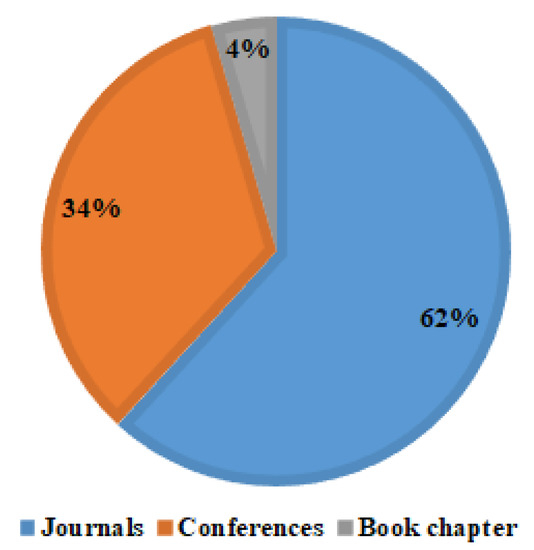

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of studies per library and the number of studies at each stage. Figure 6 shows the distribution of studies according to the publication type, i.e., journals, conferences, and books.

Figure 5.

Distribution of selected paper per library.

Figure 6.

Distribution of selected paper per publication type.

After reviewing hundreds of articles, we applied the inclusion-exclusion technique to select the most relevant papers. Lastly, the 90 most relevant studies have been chosen for SLR. The following points present the inclusion and exclusion items:

Inclusion principles:

- The study must include a technique for extracting semantic features from the source code.

- An experimental investigation of SDP is presented using deep learning models.

- The article must be a minimum of six pages.

Exclusion principles:

- The study reported without an experimental investigation of the semantic feature-based technique.

- The article has only an abstract (the accessibility of the article is not included in this criterion; both papers (open access and subscription) were included.

- The paper is not a major relevant study article.

- The study does not provide a detailed description of how deep learning is applied.

4. Results

In this section, we discuss our answers to each study question.

4.1. RQ-1: Motivation

State-of-the-art techniques focus on extracting semantic features from source code while most previous studies focused on traditional features. Standard features usually fail to detect program semantic differences, which are required for creating robust prediction models. Semantic features represent the contextual information of a source code that standard features cannot express.

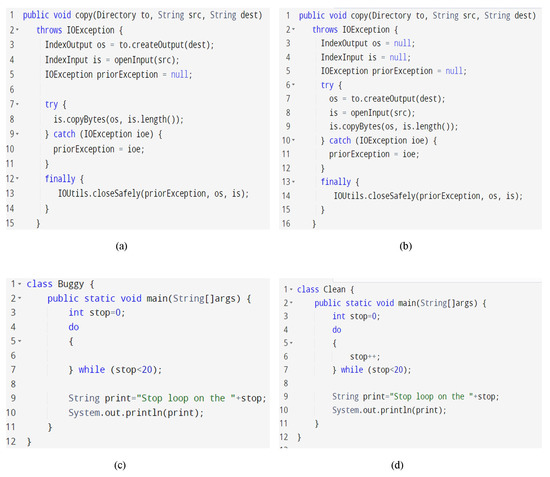

Figure 7 illustrates four java code files. For example, Figure 7a shows an original defect version (memory leak bug), and Figure 7b shows a clean version (code after fixing the bug). The code version in Figure 7a contains an IOException when the variables (‘is’ and ‘os’) are initialized before the “try” procedure. The defective code file can cause a memory leak (https://issues.apache.org/jira/browse/LUCENE-3251, we accessed this link last time on 1 August 2022), but this has been corrected in Figure 7b through shifting the initializing sentences into the try statement. In addition, the buggy code file in Figure 7c and the clean code file in Figure 7d have the same structure of do-while block; the only difference is that Figure 7c does not include the loop increment statement, which will lead to an infinite loop bug. These java code files contain the same source code properties regarding function calls, complexity, code size, etc. Using traditional features like code size and complexity to represent these two Java files will lead to equivalent feature vectors. However, these two code lines have immensely different semantic information. In this case, semantic information is required to create more accurate prediction models.

Figure 7.

Motivating Java code example. (a) Original buggy code (memory leak bug), (b) Code after fixing the memory leak bug, (c) Original buggy code (infinite loop bug), and (d) Code after fixing the infinite loop bug.

4.2. Rq-2: Source Code Representation Techniques

Different methods for source code representations are available, and various levels of granularity are needed for multiple tasks. For example, token-level embedding is required for code completion, while function clone detection needs function embedding. Several levels of granularity are used to solve the software defect prediction problem, such as component, sub-system, method, class, and change [45]. These days, the three main code representation methods are Graph-based, AST-based, and Token-based [35].

In the token-based method, the source code fragment is divided into tokens. The bag of words (BOW) representation is used to count the frequency of each token appearing in a document [46]. A token-based method requires more Central Processing Unit (CPU) time and memory than a line-by-line examination because a code line usually contains several tokens. However, the token-based approach can use several transforms, resulting in efficient elimination of coding style differences and identification of many code segments as clone pairs [47]. The source code representation can help in numerous applications to improve the shortage of memory and speed, such as cyber security [48,49], robotics [50,51], etc.

Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) is a method used to represent the source code semantic information and has been applied to software engineering tools and programming languages [52]. ASTs do not contain details such as delimiters and punctuation identifiers compared to the standard code file. In contrast, ASTs can present contextual and linguistic information about source code [53].

In the case of the graph-based method, such as control flow graph CFGs [54], program dependence graphs [55], and graph representations of programs [56], they can be applied to describe contextual information of the source code.

Each technique of code representation is carefully constructed to collect specific data that can either be applied independently or with other methods to produce a more extensive result. Then, the features carrying important information from the source code will be gathered, which can be used in code clone detection, defect prediction, automatic program repair, etc. [57].

4.3. Rq-3: Available Dataset

The lack of sizeable labeled training datasets is one of the challenges in software defect prediction. Pre-trained contextual embedding can be used to solve this issue. In this technique, the language model is pre-trained using a self-supervised process on large unlabeled datasets. These self-supervised methods used in this training are token detection, masked language modeling, and next sentence prediction. Table 3 shows a list of unlabeled source code datasets suitable for this task (see [27] for more details).

Table 3.

Unlabeled source code datasets.

Several public labeled datasets for SDP have also been generated. Table 4 shows a list of available labeled datasets used for SDP. Such datasets usually consist of pairs of faulty and correct code parts.

Table 4.

Available labeled datasets.

4.4. Rq-4: Deep Learning Techniques for Semantic Feature-Based SDP

Currently, Deep Learning (DL) is gaining popularity in the field of semantic feature-based SDP. The most popular DL techniques for SDP are Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Deep Belief Networks (DBN), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), and Transformer architecture.

LSTM is a recurrent neural network (RNN) [70]. LSTM can process entire data sequences as well as single data points. There are three components of an LSTM: cells, inputs, and outputs. The three gates manage the data flow into and out of the cell, and the cell can recall values across any timeframe.

CNN is used to analyze data with a grid-like architecture [71]. This network uses the mathematical operation known as convolution for the conventional nonlinear functions in at least one of its layers. CNN mainly consists of three layers: (1) convolutional layers, (2) nonlinear layers, and (3) pooling layers.

DBN is a neural network shown as a generative graphical model, built up of multiple layers of implicit variables (hidden units) with links between layers but not between the units inside each layer [72].

Transformer models are also used to show source code and predict software defects. Guo et al. [73] presented a multi-layer transformer model named GraphCodeBERT that uses three main inputs: source code, data flow graph, and paired comments. It assists with code clone identification, translation, refinement, and other downstream code-related processes.

4.5. Rq-5: Performance Analysis of Different Deep Learning Techniques Applied to Semantic Feature-Based SDP Models

This section discusses the SDP models based on semantic information directly extracted from source code using DL techniques. Wang et al. [23] proposed the first approach to generate the contextual information from source code and employ them in SDP. After, researchers proposed several methods to extract the contextual features from the source code using deep learning techniques. Table 5 shows the detail of semantic feature-based SDP studies, the DL techniques such as DBN, CNN, LSTM, RNN, and BERT, and the journal information, publication year, evaluation metrics, and methods used for representing source code and extracting semantic features. AST is usually used to describe the source code as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Performance analysis DL techniques applied to semantic feature-based SDP models.

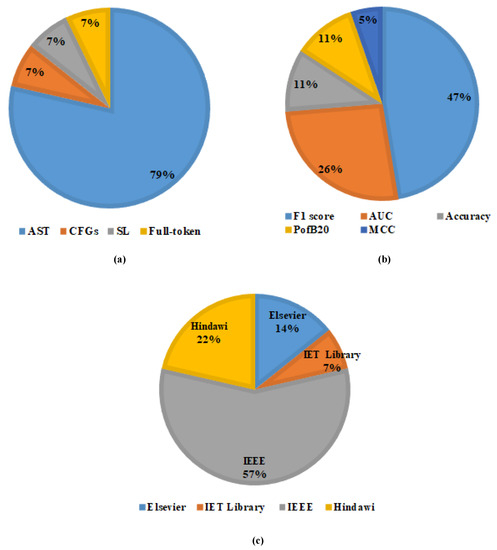

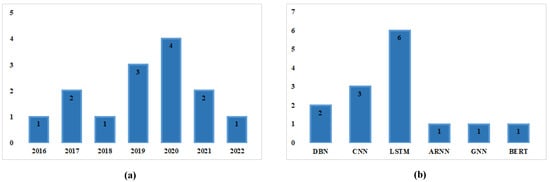

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the distribution of semantic feature-based SDP using DL. Figure 8a shows the paper distribution per code representation techniques, Figure 8b shows distribution per evaluation measures, and Figure 8c shows paper distribution per online libraries. Figure 9a shows paper distribution per year, and Figure 9b shows distribution according to DL techniques.

Figure 8.

(a) Distribution per code representation techniques, (b) Distribution per evaluation measures, and (c) Distribution per online libraries.

Figure 9.

(a) Distribution per year and (b) Distribution according to DL techniques.

4.6. Rq-5.1: Which Deep Learning Techniques Outperform Existing SDP Models?

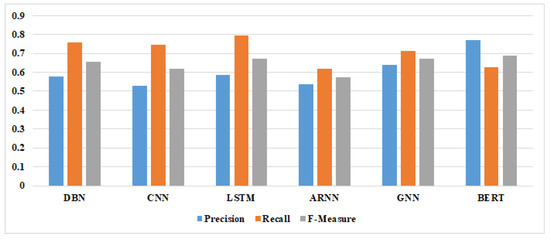

We compare the recall, f-measure, and precision of different SDP models to measure the efficiency of various semantic features-based SDP models. Table 6 shows deep learning models’ recall, f-measure, and precision of the semantic features-based SDP. The result indicates that the f-measure score for DBN models ranges between 0.645 and 0.658, CNN models range between 0.609 and 0.627, LSTM range between 0.521 and 0.696, ARNN is 0.575, GNN is 0.673, and BERT is 0.689. Table 6 shows that despite the different values for all the techniques used, they are generally comparable, with ranges between 0.521 and 0.696.

Table 6.

Recall, Precision, and F-Measure values of semantic features based-SDP using deep learning models.

Figure 10 shows the average precision, f-measure, and recall of DL techniques used in the semantic features-based SDP. The LSTM approach is the most efficient approach among all DL techniques and is the most usually utilized DL technique in the SDP area based on the results. Following DBN, CNN and BERT is also used as an SDP model in many research; BERT outperforms DBN and CNN, while DBN outperforms CNN.

Figure 10.

Average precision, recall, and f-measure of DL techniques used in the semantic features-based SDP.

4.7. Rq-6: Evaluation Metrics

In a non-effort-aware case, developers expect unlimited resources to be available when they verify the source code using the results of the SDP model, i.e., each of the predicted faulty cases can be verified. As a result, the measures used to evaluate prediction performance in this situation are identical to those used to assess performance in binary-classification tasks.

In effort-aware cases, we estimate that the software resources are confined when developers perform a code check, which is the most often used in real-time SDP techniques. In this scenario, developers or testers can only check a few instances of the predicted bugs; specifically designed metrics should evaluate the prediction performance under effort-aware scenarios.

- A.

- Non-effort-aware evaluation metrics

SDP models have four potentials for predicting the result of a code change: (1) predict a defective code change as a defect (True positive, TP), (2) Predict a defective code change as no defect (False Positive, FP), (3) Predict a non-defective code change as no defect (True Negative, TN), and (4) Predict a non-defective code change as defective (False Negative, FN). The prediction model calculates performance indicators such as recall, F-measure, precision, and UAC in the test set based on these four possibilities.

Precision represents the ratio of all correctly classified faulty changes to all incorrect faults, which is given by:

Recall refers to the ratio of all correctly faulty changes to all truly faulty changes, which is expressed by:

F-measure: A comprehensive performance indicator combines the recall and precision rates. It is the consistent average of the recall and precision rate as follows:

AUC: Area Under the Curve is a frequently used performance metric in real-time SDP research. A two-dimensional space represents the ROC curve using recall as the y-coordinate and Pf as the x-coordinate [85].

- B.

- Effort-aware evaluation metrics

Developers try to examine less code to catch as many faults as possible to detect defects more efficiently. In this study, we choose two measures that can evaluate the performance of code examination according to the findings provided by SDP models in the effort-aware scenario: PofB20 and Popt.

PofB20 is a metric for determining the ratio of defects that a programmer can find by checking 20 percent of the lines of code (LOC). When the programmer finishes inspecting 20 percent of the full code, the scores of PofB20 are referred to as the percentage of faults identified. When examining many LOC, a higher PofB20 value determines that the projects have more defects.

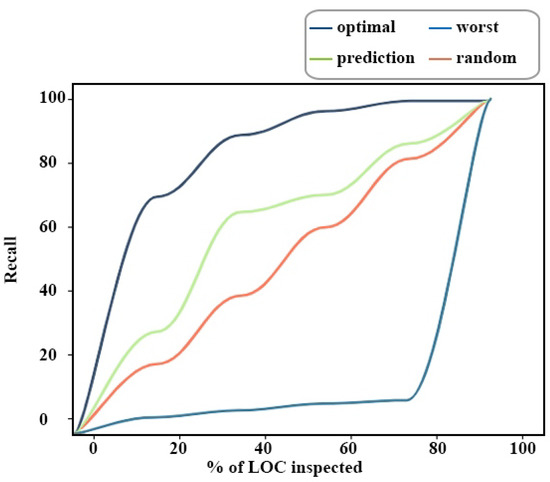

Popt is the indicator of effort-aware performance based on the Alberg diagram concept [86], which presents the prediction model performances in the effort-aware case. The x-axis displays the percentage of examined LOC, and the y-axis indicates the recall of an SDP model, as shown in Figure 11. can be derived from the prediction model (m), which is given by:

where the optimal describes situations where all data are arranged according to defect density in descending order. The worst line refers to the scenario in which the defect density of all files is arranged in ascending order.

Figure 11.

Alberg diagram example.

Researchers probably selected these measures because they are frequently used in deep learning research. Accuracy is a poor measure for defect prediction research because the SDP datasets are imbalanced. Besides accuracy, other measures must also be used to evaluate the efficiency of the SDP models, including recall, precision, and PofB20.

4.8. Rq-7: Semantic Features-Based SDP Challenges

- 1.

- Lack of context

The complexity of the source code structure is one of the problems in source code representation. Unlike natural languages, a code element may depend on a distant part, possibly even in another code fragment. Furthermore, it can be challenging to determine whether a coding unit is defective without understanding its context. It can be challenging to determine the essence of a defect when the dataset comprises pairs of faulty and correct code parts [27]. The similarity of code components is also essential in defect prediction tasks. In most cases, code similarity depends on manually defined or hand-crafted criteria, such as evaluating identifier overlap or comparing two code components’ AST [87].

According to recent studies, DL can efficiently replace hand-crafted features for the task of code representation when using a stream of identifiers. Different levels of abstraction can be used to define source code using identifiers, AST, Bytecode, and CFG. We suggest that each part format can give a unique yet related view of the same segment to enable more robust code similarity detection.

- 2.

- Lack of data

Lack of sufficient labeled datasets for semantic features-based SDP is one of the difficulties. To avoid this limitation, developers can use pre-trained contextual word embedding. The language model is pre-trained using self-supervised on many unlabeled datasets in this method. Such self-supervised methods used in this training are token detection, masked language modeling, and next sentence prediction. Table 3 shows a list of the standard unlabeled datasets appropriate for SDP.

In addition, the distribution of the classes can also be a factor that affects the difficulty of building datasets in real software projects. A project often has fewer faulty files or procedures than valid ones. Consequently, the standard classifiers may correctly identify the main classification (clean code) but discard the smaller category of defect-prone code.

5. Discussion

This section presents the systematic literature review’s general discussion and validity issues.

5.1. General Discussion

This study analyzes and evaluates semantic features-based SDP using deep learning techniques. This topic has not been addressed in any similar SLR studies. Therefore, we conducted this SLR study to answer the research questions that we established in the previous section. We expect the findings and recommendations will open way for additional studies and benefit scholars and practitioners in this area. The following are brief discussions of responses to survey questions:

RQ-1: We discussed the motivation for extracting semantic features from source code and using them in SDP. We explained the weakness of standard metrics used in most SDP studies and illustrated a detailed example of this point. Furthermore, we discussed the need for semantic information to create more accurate prediction models.

RQ-2: We presented several techniques of source code representation, including Graph-based, AST-based, and Token-based code representation. We also noticed that different granularities are needed for various tasks; e.g., token-level embedding is required for code completion, but function embedding is necessary for function clone detection. Several levels of granularity are used to solve the software defect prediction problem, such as component, sub-system, method, class, and change.

RQ-3: Various datasets have been collected for defect prediction in git or Github repositories. Practitioners and scholars widely use these repositories. As a result, these platforms are found in where most of the datasets are located. There are groups of labeled datasets and others related to the open-source nature without labeled. A few datasets also made use of other types of media. Their percentage was smaller compared to using repositories connected to Github.

RQ-4: The researchers used DL techniques to extract contextual information for semantic features-based SDP models from the source code. Various DL techniques are currently gaining popularity in the field of semantic feature-based SDP. DBN, LSTM, CNN, and Transformer architecture are the most widely used DL techniques for SDP.

RQ-5: We analyzed the performance of different DL techniques applied to semantic feature-based SDP models. Wang et al. [23] created the first model based on semantic features in 2016 using DBN; we analyzed the performance of the studies published between 2016 and 2022. The analysis process includes the type of DL techniques used in prediction and evaluation measures used to evaluate the model performance.

RQ-5.1: In this section, we compared the efficiency of various semantic features-based SDP models. We used f-measure, recall, and precision to measure the performance of different SDP models. We noticed that the LSTM approach is the most often used DL technique in the SDP sector. DBN, CNN, and BERT are also used as SDP model in several studies; BERT performs better than DBN and CNN, while DBN performs better than CNN.

RQ-6: Most studies used Recall, Precision, AUC, and F-measure metrics to evaluate the SDP model performance in cases of Non-effort-Aware. They also used PofB20 and Popt to measure the performance under Effort-Aware conditions. Researchers probably selected these measures because they are frequently used in deep learning research. Accuracy is a poor measure for defect prediction research because the SDP datasets are imbalanced. Besides accuracy, other measures must also be used to evaluate the efficiency of the SDP models, including recall, precision, and PofB20.

RQ-7: Unlike natural languages, collecting contextual information from the source code faced several challenges. The complexity of the source code structure is one of the challenges with source code representation. A code fragment can be dependent on a far-off component or even be found in another code fragment. It can be challenging to assess whether it is flawed without knowing the context of a coding unit. Furthermore, the lack of sufficiently labeled datasets for semantic features-based SDP is one of the challenges. To solve this problem, developers can employ contextual word embedding with pre-training. This strategy pre-trains the language model using self-supervised learning on many unlabeled datasets.

5.2. Threats to Validity

Three different kinds of validity threats can compromise the validity of our study, according to Wohlin et al. [88]. The following sections explain each of these.

5.2.1. Conclusion Validity

Threats to the validity of the conclusions are focused on the problems that limit the ability to draw accurate conclusions and if the survey can be repeated. We have established a selection of primary studies that have easily accessible papers available to reduce these threats. This step will allow us to replicate the experiment and confirm the findings. Publication bias can be a threat to the validity of the conclusions [89,90]. This threat relates to studies that have been rejected by editors or reviewers, as well as documents that writers have not submitted or published because they might be recognized as unimportant. Such studies might change the conclusions of our evaluation. However, we decided not to include them due to the difficulty in locating them and the possibility that they are of lower quality because they have not been put through the rigorous scientific scrutiny of a peer review process.

5.2.2. Internal Validity

These threats are linked to the aspects that may impact the outcome of our analysis. They also affect the selection of the papers in terms of internal validity. In this section, according to Wohlin et al. [88], we should take the selection of publications and instrumentation into account. The key indicators of publication selection are digital libraries, keywords, time frame, and publication language. Instrumentation-wise, it primarily relates to the venues taken into account by the used digital libraries.

We identified articles from eight digital platforms as discussed in Section 3.3 and used an SLR process as mentioned in Section 3.1 using our search criteria. The authors conducted multiple meetings to reduce the researcher’s bias. However, we may have missed some papers in some digital libraries while conducting this study. In addition, since new studies are released frequently, we might have missed some recently published articles. The usage of the search criteria poses another danger. There may have been additional synonyms used in our study, so that we may have overlooked specific studies.

5.2.3. External Validity

These threats relate to the generalizability of this study’s findings and conclusions. In this study, we do not intend to generalize since it is on a specific topic. Our study refers to published studies on deep learning-based SDP via semantic features of source code, hence it cannot be applied to any other similar area of study.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study provides the survey of an SLR on semantic features-based software defect prediction using DL. We conducted a thorough study to discuss the performance of various DL techniques over semantic features-based SDP models. A total of 283 studies were gathered from electronic resources; 90 articles were considered after applying the research selection criteria. The selected articles are organized according to code representation techniques, deep learning types, datasets, evaluation metrics, best deep learning techniques, gaps, and challenges, and the related results are presented. Researchers mostly preferred the AST method to represent source code and extract the semantic features. Furthermore, several repositories and datasets exist for semantic features-based SDP studies. Researchers also used deep learning for building semantic features-based SDP models; LSTM is commonly used in these tasks.

This study will help software developers, and researchers analyze and evaluate SDP modeling. They will select more deep learning techniques and code representation methods under various scenarios; they can identify the relationships between the type of projects, code representation methods, deep learning techniques, and required evaluation measures over such situations. In addition, it will enable them to handle various SDP-related threats and difficulties.

The following are future recommendations for researchers and software developers in the SDP field:

- There should be a more general outcome of various semantic features-based SDP approaches; only a few studies have been studied in generalized methods. When the researcher adopts this perspective, it will be possible to compare SDP’s efficiency and performance.

- Industries should have free access to the dataset to conduct more research experiments for SDP. Researchers and developers should reduce the demand for labeled datasets of large size; they should apply self-supervised learning to large amounts of unlabeled data. They should add more features and test cases so DL can be easily used without overfitting.

- It is essential to compare the performance of DL techniques to other DL /Statistical approaches to assess their potential comparison to SDP.

- Mobile applications have received widespread attention because of their simplicity, portability, timeliness, and efficiency. The business community is constantly developing office and mobile applications suitable for various scenarios. Therefore, SDP techniques can also be applied to mobile application-based architecture. Practitioners should precisely be taking further care to explore the applicability of existing approaches in mobile applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.; Data curation, H.A.A.; Formal analysis, R.A.; Funding acquisition, K.H. and M.A.A.-a.; Project administration, Z.Z.; Resources, H.A.A.; Software, A.A.; Supervision, Z.Z.; Writing—original draft, A.A.; Writing—review & editing, R.A., K.H. and M.A.A.-a. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sejong University Industry-University Cooperation Foundation under the project number (20220224) and by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Korea (2020R1A2C1004720).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the fund sponsors of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDP | Software Defect Prediction |

| CPDP | Cross Project Defect Prediction |

| WPD | PWithin Project Defect Prediction |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| AST | Abstract Syntax Trees |

| CFG | Control Flow Graph |

| OO | Object-Oriented |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DBN | Deep Belief Networks |

| LSTM | Long Short Term Memory |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| NB | Naive Bayes |

| NN | Neural Network |

| KTSVM | Kernel Twin Support Vector Machines |

References

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, N.; Ying, S.; Wang, X. Within-project and cross-project software defect prediction based on improved transfer naive bayes algorithm. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2020, 63, 891–910. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Ying, S.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, D. Software defect prediction based on enhanced metaheuristic feature selection optimization and a hybrid deep neural network. J. Syst. Softw. 2021, 180, 111026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, K.; Luo, S.; Varadharajan, V.; Hameed, I.A.; Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Li, J. Performance comparison and current challenges of using machine learning techniques in cybersecurity. Energies 2020, 13, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algabri, R.; Choi, M.T. Deep-learning-based indoor human following of mobile robot using color feature. Sensors 2020, 20, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algburi, R.N.A.; Gao, H.; Al-Huda, Z. A new synergy of singular spectrum analysis with a conscious algorithm to detect faults in industrial robotics. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 7565–7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghodhaifi, H.; Lakshmanan, S. Autonomous vehicle evaluation: A comprehensive survey on modeling and simulation approaches. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 151531–151566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Huda, Z.; Peng, B.; Yang, Y.; Algburi, R.N.A. Object scale selection of hierarchical image segmentation with deep seeds. IET Image Process. 2021, 15, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Al-Huda, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wu, X. Multi-scale region composition of hierarchical image segmentation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 32833–32855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.M.; Shaukat, K.; Hameed, I.A.; Khan, W.A.; Sarwar, M.U.; Iqbal, F.; Luo, S. A novel framework for prognostic factors identification of malignant mesothelioma through association rule mining. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, K.; Alam, T.M.; Ahmed, M.; Luo, S.; Hameed, I.A.; Iqbal, M.S.; Li, J.; Iqbal, M.A. A model to enhance governance issues through opinion extraction. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th IEEE Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4–7 November 2020; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, T.J. A complexity measure. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1976, 4, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, M.H. Elements of Software Science (Operating and Programming Systems Series); Elsevier Science Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Chidamber, S.R.; Kemerer, C.F. A metrics suite for object oriented design. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1994, 20, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, R.; Counsell, S.J.; Nithi, R.V. An evaluation of the MOOD set of object-oriented software metrics. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1998, 24, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Tan, L.; Kim, S. Personalized defect prediction. In Proceedings of the 2013 28th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), Silicon Valley, CA, USA, 11–15 November 2013; pp. 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- e Abreu, F.B.; Carapuça, R. Candidate metrics for object-oriented software within a taxonomy framework. J. Syst. Softw. 1994, 26, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elish, K.O.; Elish, M.O. Predicting defect-prone software modules using support vector machines. J. Syst. Softw. 2008, 81, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, W.h. Naive bayes software defect prediction model. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Software Engineering, Wuhan, China, 10–12 December 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Erturk, E.; Sezer, E.A. A comparison of some soft computing methods for software fault prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 1872–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayatri, N.; Nickolas, S.; Reddy, A.; Reddy, S.; Nickolas, A. Feature selection using decision tree induction in class level metrics dataset for software defect predictions. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–22 October 2010; Volume 1, pp. 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, H.; Wu, G.; Yu, M.; Yuan, M. Software defect prediction based on cost-sensitive dictionary learning. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Knowl. Eng. 2019, 29, 1219–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C. Cross-project software defect prediction based on domain adaptation learning and optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 171, 114637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Tan, L. Automatically learning semantic features for defect prediction. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM 38th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Austin, TX, USA, 14–22 May 2016; pp. 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Nam, J.; Tan, L. Deep semantic feature learning for software defect prediction. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2018, 46, 1267–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Lu, M.; Xu, B. An empirical study on software defect prediction using codebert model. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Mishra, R.B.; Tripathi, A.K. Machine learning based methods for software fault prediction: A survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 172, 114595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimova, E.N.; Bersenev, A.Y.; Deikov, A.A.; Kobylkin, K.S.; Konygin, A.V.; Mezentsev, I.P.; Misilov, V.E. A survey on software defect prediction using deep learning. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catal, C.; Diri, B. A systematic review of software fault prediction studies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 7346–7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.; Beecham, S.; Bowes, D.; Gray, D.; Counsell, S. A systematic literature review on fault prediction performance in software engineering. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2011, 38, 1276–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Turhan, B.; Gunarathna, D. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis on cross project defect prediction. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2017, 45, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, A.O.; Basri, S.; Mahamad, S.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Almomani, M.A.; Adeyemo, V.E.; Al-Tashi, Q.; Mojeed, H.A.; Imam, A.A.; Bajeh, A.O. Impact of feature selection methods on the predictive performance of software defect prediction models: An extensive empirical study. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, X.; Liu, Y. Non-negative sparse-based SemiBoost for software defect prediction. Softw. Test. Verif. Reliab. 2016, 26, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Jing, X.Y.; Sun, Y.; Sun, J.; Huang, L.; Cui, F.; Sun, Y. Cross-project and within-project semisupervised software defect prediction: A unified approach. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2018, 67, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Jing, X.Y.; Wang, T.J. Label propagation based semi-supervised learning for software defect prediction. Autom. Softw. Eng. 2017, 24, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Sui, Y.; Wan, Y.; Liu, G.; Xu, G. Fcca: Hybrid code representation for functional clone detection using attention networks. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2020, 70, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1532–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2013, 26, 3111–3119. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Zimmermann, T.; Pan, K.; James, E., Jr. Automatic identification of bug-introducing changes. In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE’06), Tokyo, Japan, 18–22 September 2006; pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Śliwerski, J.; Zimmermann, T.; Zeller, A. When do changes induce fixes? ACM Sigsoft Softw. Eng. Notes 2005, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R. A systematic review of machine learning techniques for software fault prediction. Appl. Soft Comput. 2015, 27, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jing, X.Y.; Zhu, X. Progress on approaches to software defect prediction. IET Softw. 2018, 12, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, S.S.; Kumar, S. A study on software fault prediction techniques. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 51, 255–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Shepperd, M.; Guo, Y. A systematic review of unsupervised learning techniques for software defect prediction. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2020, 122, 106287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering—A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2009, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allamanis, M.; Barr, E.T.; Devanbu, P.; Sutton, C. A survey of machine learning for big code and naturalness. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajnani, H.; Saini, V.; Svajlenko, J.; Roy, C.K.; Lopes, C.V. Sourcerercc: Scaling code clone detection to big-code. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Software Engineering, Austin, TX, USA, 14–22 May 2016; pp. 1157–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya, T.; Kusumoto, S.; Inoue, K. CCFinder: A multilinguistic token-based code clone detection system for large scale source code. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2002, 28, 654–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, K.; Luo, S.; Varadharajan, V.; Hameed, I.A.; Xu, M. A survey on machine learning techniques for cyber security in the last decade. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 222310–222354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, K.; Luo, S.; Chen, S.; Liu, D. Cyber threat detection using machine learning techniques: A performance evaluation perspective. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security (ICCWS), Virtual Event, 20–21 October 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Algabri, R.; Choi, M.T. Target recovery for robust deep learning-based person following in mobile robots: Online trajectory prediction. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algabri, R.; Choi, M.T. Robust person following under severe indoor illumination changes for mobile robots: Online color-based identification update. In Proceedings of the 2021 21st International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Jeju, Korea, 12–15 October 2021; pp. 1000–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, I.D.; Yahin, A.; Moura, L.; Sant’Anna, M.; Bier, L. Clone detection using abstract syntax trees. In Proceedings of the Proceedings. International Conference on Software Maintenance (Cat. No. 98CB36272), Bethesda, MD, USA, 20–20 November 1998; pp. 368–377. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, K.; Liu, X. A novel neural source code representation based on abstract syntax tree. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM 41st International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–31 May 2019; pp. 783–794. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, F.E. Control flow analysis. ACM Sigplan Not. 1970, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, M.; Jiang, L.; Su, Z. Scalable detection of semantic clones. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Software Engineering, Leipzig, Germany, 10–18 May 2008; pp. 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi, J.; Sedaghat, Y.; Rezaee, M. Masking wrong-successor Control Flow Errors employing data redundancy. In Proceedings of the 2015 5th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), Mashhad, Iran, 29–29 October 2015; pp. 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhuang, W.; Zhang, X. Software defect prediction based on gated hierarchical LSTMs. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2021, 70, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, U.; Brody, S.; Levy, O.; Yahav, E. code2seq: Generating sequences from structured representations of code. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.01400. [Google Scholar]

- Allamanis, M.; Sutton, C. Mining source code repositories at massive scale using language modeling. In Proceedings of the 2013 10th Working Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–19 May 2013; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kanade, A.; Maniatis, P.; Balakrishnan, G.; Shi, K. Learning and evaluating contextual embedding of source code. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual Event, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 5110–5121. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S.; Konstas, I.; Cheung, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. Summarizing source code using a neural attention model. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; pp. 2073–2083. [Google Scholar]

- Allamanis, M.; Brockschmidt, M.; Khademi, M. Learning to represent programs with graphs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.00740. [Google Scholar]

- Bryksin, T.; Petukhov, V.; Alexin, I.; Prikhodko, S.; Shpilman, A.; Kovalenko, V.; Povarov, N. Using large-scale anomaly detection on code to improve kotlin compiler. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories, Seoul, Korea, 29–30 June 2020; pp. 455–465. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambros, M.; Lanza, M.; Robbes, R. Evaluating defect prediction approaches: A benchmark and an extensive comparison. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2012, 17, 531–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, Y.; Shihab, E.; Adams, B.; Hassan, A.E.; Mockus, A.; Sinha, A.; Ubayashi, N. A large-scale empirical study of just-in-time quality assurance. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2012, 39, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Zhang, H.; Kim, S.; Cheung, S.C. Relink: Recovering links between bugs and changes. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM SIGSOFT Symposium and the 13th European Conference on Foundations of Software Engineering, Szeged, Hungary, 5–9 September 2011; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yatish, S.; Jiarpakdee, J.; Thongtanunam, P.; Tantithamthavorn, C. Mining software defects: Should we consider affected releases? In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM 41st International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–31 May 2019; pp. 654–665. [Google Scholar]

- Jureczko, M.; Madeyski, L. Towards identifying software project clusters with regard to defect prediction. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Predictive Models in Software Engineering, Timişoara, Romania, 12–13 September 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, F.; Menzies, T. Privacy and utility for defect prediction: Experiments with morph. In Proceedings of the 2012 34th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Zurich, Switzerland, 2–9 June 2012; pp. 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 2006, 18, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Ren, S.; Lu, S.; Feng, Z.; Tang, D.; Liu, S.; Zhou, L.; Duan, N.; Svyatkovskiy, A.; Fu, S.; et al. Graphcodebert: Pre-training code representations with data flow. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.08366. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, A.V.; Le Nguyen, M.; Bui, L.T. Convolutional neural networks over control flow graphs for software defect prediction. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 29th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Boston, MA, USA, 6–8 November 2017; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; He, P.; Zhu, J.; Lyu, M.R. Software defect prediction via convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security (QRS), Prague, Czech Republic, 25–29 July 2017; pp. 318–328. [Google Scholar]

- Meilong, S.; He, P.; Xiao, H.; Li, H.; Zeng, C. An approach to semantic and structural features learning for software defect prediction. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6038619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, H.K.; Pham, T.; Ng, S.W.; Tran, T.; Grundy, J.; Ghose, A.; Kim, T.; Kim, C.J. Lessons learned from using a deep tree-based model for software defect prediction in practice. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM 16th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–31 May 2019; pp. 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Majd, A.; Vahidi-Asl, M.; Khalilian, A.; Poorsarvi-Tehrani, P.; Haghighi, H. SLDeep: Statement-level software defect prediction using deep-learning model on static code features. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 147, 113156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Lu, L.; Qiu, S. Software defect prediction via LSTM. IET Softw. 2020, 14, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Xie, Z. Seml: A semantic LSTM model for software defect prediction. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 83812–83824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lu, L. Semantic feature learning via dual sequences for defect prediction. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 13112–13124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Diao, X.; Yu, H.; Yang, K.; Chen, L. Software defect prediction via attention-based recurrent neural network. Sci. Program. 2019, 2019, 6230953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, F.; Ai, J. Defect prediction with semantics and context features of codes based on graph representation learning. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2020, 70, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Li, B.; Ali, Z.; Kefalas, P.; Khan, I.; Zada, I. Software defect prediction employing BiLSTM and BERT-based semantic feature. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 7877–7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessmann, S.; Baesens, B.; Mues, C.; Pietsch, S. Benchmarking classification models for software defect prediction: A proposed framework and novel findings. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2008, 34, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mende, T.; Koschke, R. Effort-aware defect prediction models. In Proceedings of the 2010 14th European Conference on Software Maintenance and Reengineering, Madrid, Spain, 15–18 March 2010; pp. 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Tufano, M.; Watson, C.; Bavota, G.; Di Penta, M.; White, M.; Poshyvanyk, D. Deep learning similarities from different representations of source code. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACM 15th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), Gothenburg, Sweden, 27 May–3 June 2018; pp. 542–553. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlin, C.; Runeson, P.; Höst, M.; Ohlsson, M.C.; Regnell, B.; Wesslén, A. Experimentation in Software Engineering; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, A.; Lee, P. Publication bias in meta-analysis: Its causes and consequences. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2000, 53, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troya, J.; Moreno, N.; Bertoa, M.F.; Vallecillo, A. Uncertainty representation in software models: A survey. Softw. Syst. Model. 2021, 20, 1183–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).