Abstract

This study examined the effectiveness of professional development for inclusive education and best practices through a short-term technical assistance (TA) model across 15 schools. The professional development was structured to enhance school professionals’ knowledge about inclusion as a concept, as well as best practices in inclusive education. Topics included the use of accommodations and modifications, differentiation and Universal Design for Learning (UDL), building an inclusive school culture, and co-teaching. Pre- and post-test measures were utilized to measure participants’ growth in the knowledge of these topics. Descriptive statistics and dependent t-tests were utilized to analyze data across all topic areas. The findings indicate that short-term TA models of professional development prove beneficial for improving attitudes and beliefs in inclusive education for content knowledge and building an inclusive school culture. Short-term TA did not yield statistically significant increases for classroom strategies or implementation, suggesting that more intensive professional development models need to be incorporated as a wider professional development plan for using best practices in inclusive education by school professionals.

1. Introduction

As new research, pedagogical frameworks, and conceptual models are developed, teachers need continued training to offer best practices to the students in their classrooms. In United States school systems, teacher professional development is widely utilized as a means of improving practice and skills (Kennedy, 2016). While there are many areas of focus for professional development, there is a strong emphasis placed on training special education teachers to use evidence-based practices, especially regarding inclusive education (Love & Horn, 2021). Research has consistently indicated that schools face difficulty incorporating inclusive practices, and teacher training is often identified as a major factor contributing to this struggle (DeMatthews & Mawhinney, 2014; Kart & Kart, 2021).

Various models for professional development are utilized when designing, developing, and implementing professional development sessions (Çetin & Bayrakcı, 2019). Short-term technical assistance (TA) is one model that is used in the school system. Short-term TA provides a focused approach to meeting specific needs, often incorporating a variety of tools, such as training, coaching, and consultation (Scott et al., 2022). While short-term TA is a proven practice, there are limited data that demonstrate its impact on improving inclusive educational practices (Donath et al., 2023).

Building on previous research conducted by our research team that was focused exclusively on content knowledge acquisition through a virtual delivery model (Montalbano et al., 2024), this study seeks to examine the effectiveness of short-term TA on school-based professionals’ content knowledge of inclusive practices, as well as attitudes, beliefs, and self-efficacy, as an in-person method for training educational professionals. Including the examination of attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion and self-efficacy related to best practices provides a further understanding of short-term TA efficacy, as it integrates the factors that have been shown to influence and change educator behaviors in the classroom (Weber & Greiner, 2019). The short-term TA provided to the teachers incorporates evidence-based practices, such as co-teaching, Universal Design for Learning (UDL), using modifications and accommodations, and more (McLeskey et al., 2017). This study is guided by the following research question:

RQ1: What impact does a short-term TA model of professional development in inclusive education have on participants’ content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about inclusion, and self-efficacy in implementing best practices?

1.1. The Role of Professional Development in Schools

Schools have been called to adopt a long-term process of continuous improvement, where members of a school community identify significant problems of practice and holistically engage in a change process (Shakman et al., 2020). Over the past several decades, researchers have examined how schools can become “learning organizations”, where professional growth and organizational improvement are the norms (Harris & Jones, 2018). This is often accomplished through improvement in internal processes and structures, as in the rise in popularity of the Professional Learning Community (PLC) model (DuFour, 2004), and through new external sources of practice and improvement via educator training and professional development. Professional development is an essential tool for increasing teacher knowledge, which, in turn, improves pedagogy (Borg, 2018). In addition, professional development provides the link between new research and classroom practice (Ehlert & Souvignier, 2023), with the ultimate goal of improving student outcomes (Postholm, 2018).

While widely accepted as a means of helping teachers improve the quality of teaching practice, there is no set framework or method that clearly defines professional development (Sancar et al., 2021). This creates an opportunity for school leaders to employ a wide range of possible professional development approaches. These can include school-wide efforts from experts in the field to in-house professional development offered amongst professional peers (Postholm, 2018). As school professionals carry a wide array of responsibilities, different scopes of practice in content, and address actions outside of instruction, such as behavior and management, the variety of professional development options is beneficial (Kennedy, 2016). It is essential that professional development activities be effective in order to create meaningful change (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). This might mean addressing some of the core purposes of professional development, as described by Sims et al. (2023):

The first purpose of PD is therefore to provide insight, which we define as teachers gaining a deeper understanding of how teaching and learning occur in the classroom. […] the second purpose of PD is therefore to build teachers’ motivation to change. [… the] third purpose of PD is therefore developing technique, which we define as helping a teacher to utilize a new teaching practice. [Emphasis in original].(p. 216)

These goals of insight, motivation to change, and development of techniques are theorized as important foundational goals of professional development programs.

Numerous studies have examined what constitutes high-quality professional development (Sancar et al., 2021), and though there is no broad consensus (Sims et al., 2023), scholars like Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) have enumerated several characteristics of effective professional development approaches. These professional development training structures are “content focused”, “incorporate active learning strategies”, “engage teachers in collaboration”, “use models and/or modeling”, “provide coaching and expert support”, “include time for feedback and reflection”, and “are of sustained duration” (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017, p. 23). There is evidence that professional development training structures that are limited in duration, as in the often widespread one-time in-service sessions or one-off workshops, will likely not produce a durable change in practice (Desimone, 2009).

1.2. Professional Development for Special Education Inclusion

In the United States, special education is guided by the federal law known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (2004). This law guides the provision of specialized educational services to students identified and classified with a disability. Within the constructs of the law, there is a stipulation that students with disabilities be ensured “access to the general education curriculum in the regular classroom, to the maximum extent possible” (20 U.S.C. §§1400 (c) (5)). This, along with phrasing in the law indicating that “To the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities […] are educated with children who are nondisabled” (34 CFR §300.114), is often used as the legal basis to provide special education services in an inclusive setting as much as possible, which warrants appropriate knowledge, skills, and employment of best practices in inclusive education. However, phrases like “inclusion” or “inclusive settings” are not present in the law, and the overall goals of inclusion remain in dispute with researchers and practitioners (Kauffman et al., 2023).

Nevertheless, research has broadly supported the positive effects of inclusion, including recent work by Gee et al. (2020) in their matched-pairs study of students with extensive support needs, who found positive academic, social, and curricular benefits for access to the general education setting. Still, barriers to inclusive change persist, such as a lack of effective training, negative attitudes toward inclusion, and a lack of knowledge of instructional techniques, all of which can hinder students with disabilities from being effectively educated in the inclusion setting (Grant & Jones-Goods, 2016). Scholars seeking to understand the creation of effective inclusive schools have expanded into several areas, including the role of district-level administrators and school principals in fostering inclusive change (Coviello & DeMatthews, 2021; DeMatthews et al., 2020), developing mindsets and school cultures supportive of inclusion (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; Billingsley & Bettini, 2019), implementing multi-tiered systems of support and co-teaching models (Batsche, 2014; Scruggs et al., 2007), and curriculum modification for students with disabilities (Lee et al., 2010). The role of professional development in addressing school-wide problems of practice-related inclusion will be discussed in further detail below.

1.3. Content Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Inclusion, and Self-Efficacy

Providing professional development for teachers in empirically supported domains is essential for promoting inclusive practices in schools and requires knowledge of pedagogical best practices. In a recent compendium of strategies to support more inclusive schools, the Federal Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services highlights that local districts should be “providing professional development opportunities for administrators, general and special educators, specialized instructional support personnel (e.g., school counselors, school social workers, school psychologists), paraprofessionals, and other school-based personnel to support the implementation of inclusive educational practices” (U.S. Department of Education, 2025, p. 27). As a result of this kind of training, teacher self-efficacy can be positively impacted, as professional development in co-teaching has been shown to increase teachers’ beliefs in their ability to manage classroom behavior (Colson et al., 2021). Consistent with the previously described finding that longer “duration” programs are more effective, the amount of time attending PD increases this confidence (Colson et al., 2021).

Co-teaching, or having a class taught by two teachers with different expertise, has been identified as best practice supported by research. Scholars have observed the effectiveness of co-teaching in increasing academic achievement for students with disabilities, as well as their classmates without disabilities (Jones & Winters, 2023; Hang & Rabren, 2009). For teachers in a co-teaching setting, utilization of co-teaching strategies can increase with professional development (Bundock et al., 2023). Professional development can also impact teachers’ perception of co-teaching (Bundock et al., 2023). Since co-teaching supports inclusion in the general education classroom, co-teaching professional development can impact access to the curriculum for students with disabilities.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is another recognized best practice in inclusive education. UDL is an approach that uses flexibility to meet the needs of all students through multiple means of engagement, differentiated instructional techniques and activities, and the flexible expression of mastery of content (Canter et al., 2017). UDL is proven to improve learning processes for students (Capp, 2017). One study in particular compared math and reading test scores of students in classrooms where UDL was implemented to varying degrees. Students receiving instruction in a classroom with a greater amount of UDL implemented scored higher in both reading and math assessments (Cole et al., 2023). Given the efficacy of UDL, it is essential to provide professional development for educators. Teacher attendance at professional development focusing on UDL can increase the use of UDL in the classroom (Craig et al., 2022). UDL professional development can also increase teacher confidence in their own use of UDL in the classroom (Swinth, 2018). As teachers learn, they feel empowered to implement the tenets of UDL in their classrooms.

Attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion can also be impacted by professional development. This is an important consideration as the establishment of inclusive practices and inclusion models is greatly impacted by teachers’ beliefs and support of inclusion (Weber & Greiner, 2019). A systematic literature review conducted by Holmqvist and Lelinge (2021) indicated that professional development leads to increased positive attitudes toward inclusion. As teacher attitudes shift to embrace inclusive practices, students benefit through increased differentiation and more positive classroom management techniques (Weber & Greiner, 2019). Self-efficacy plays a role in this shift. Bandura (1997) explains that self-efficacy is a person’s belief in their ability “to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (p. 3). Self-efficacy influences numerous aspects of teacher practice, including the implementation of inclusive practices (Woodcock & Hardy, 2023). High levels of teacher self-efficacy have been shown to have positive impacts on both teachers and students (Woodcock et al., 2022). This study was designed to examine how a short-term TA model can be used as a professional development method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The goal of this study was to examine and understand the impact of a short-term TA model of professional development in inclusive education focused on participants’ content knowledge about specific topics, attitudes and beliefs about inclusion, and self-efficacy in implementing best practices. Consistent with previous research conducted by our research team (Montalbano et al., 2024), we hypothesized that participants would exhibit statistically significant growth in content knowledge. Additionally, we hypothesized that participants would also display statistically significant growth in attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion and self-efficacy with regard to implementing best practices in inclusive education. To examine changes in content knowledge, attitude and beliefs, and self-efficacy, we utilized a within-subjects, repeated measures design where all participants completed pre- and post-assessments of each of the constructs at the beginning and end of the short-term TA opportunity, respectively. The short-term TA model implementation and data collection were completed through a statewide grant. This study was completed as a secondary analysis of data and, therefore, determined to be exempt by the IRB.

2.2. Participants

Participants of this study included educators from schools serving students in grades kindergarten through twelve who took part in short-term TA opportunities as part of the statewide grant in a northeastern US state. Data were gathered during the 2023–2024 school year. Schools accepted to participate extended across the state’s northern, central, and southern regions and generally reported lower district- and school-level inclusion rates. A total of 15 schools participated in the short-term TA support geared toward improving content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy around best practices in inclusive education. Participating schools included 3 lower elementary schools, 1 middle elementary school, 4 combined elementary/middle schools, 4 middle schools, and 3 high schools.

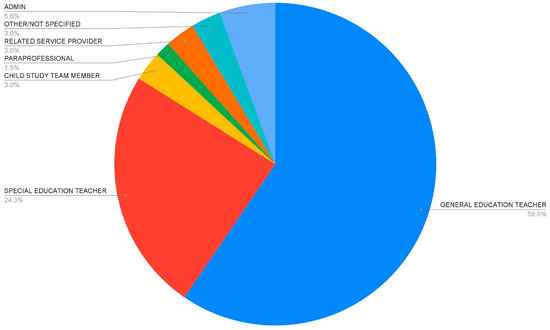

In total, there were 267 participants who took part in short-term TA opportunities across topic areas. Participants were selected by their schools to participate and were strongly encouraged to participate in all facets of support. The sample, which included participants of Sessions 2 and 5, included 42 males, 214 females, and 11 individuals whose gender was unspecified. Participants mainly included general and special education teachers; however, other participants included administrators, related service providers, child study team members, instructional aides, and other school staff members. See Figure 1 for a breakdown of the roles represented in this study.

Figure 1.

Overview of participant roles across short-term TA topics.

2.3. Overview of the Short-Term TA Model

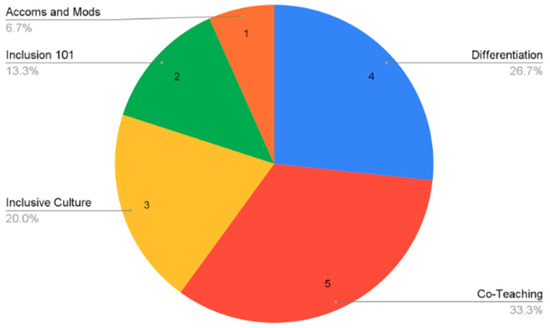

Each participating school was offered the opportunity to self-select a preferred topic related to inclusive education based on their individual school needs. Options for topics, similar to our prior study (Montalbano et al., 2024), included Introduction to Inclusive Education (Inclusion 101), Building an Inclusive School Culture (Inclusive Culture), Universal Design for Learning (UDL), Co-Teaching, Utilizing Differentiation to Support Inclusive Education (Differentiation), Best Practices in Developing IEPs that Support Inclusive Education (Best Practices IEPs), Supporting Positive Behavior Through Motivation and Engagement (Supporting Positive Behavior), Operationalizing Modifications and Accommodations (Mods and Accoms), and Collaborative Consultation (Collab Cons). The collection of topics offered was influenced by the preferences of the grant funding agency, state-specific needs related to inclusive education, and the alignment of topics with best practices. The topics selected by schools are highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Short-term TA topics selected by schools.

All short-term TA support included five sessions that followed the structure highlighted in Table 1. Inclusion facilitators employed by grant funding provided support to schools. Each school was assigned one inclusion facilitator. Inclusion facilitators were experienced consultants and coaches with extensive experience teaching and implementing best practices across all grade levels in inclusive schools.

Table 1.

Structure of five sessions.

Session 1, which included only administrators, was conducted virtually for between 40 and 60 min, and the remainder of the sessions were delivered in person at the school sites. Session 1 was designed to help administrators gather a more comprehensive understanding of short-term TA support and potential topics. During this session, inclusion facilitators discussed topic offerings and guided administrators in their topic selection. In addition, inclusion facilitators discussed scheduling, and other administrative facilitators for successful implementation.

Session 2, which was typically two hours in duration, consisted of topic-specific content delivery for all participants, as well as the collection of pre-assessment data. As discussed above, key content covered by inclusion facilitators for each topic is highlighted in Table 2. During content delivery sessions, inclusion facilitators strategically provided information and resources related to state-specific legal codes, research findings, definitions, historical foundations, overarching principles, and practical applications. Inclusion facilitators also led participants in discussions around beliefs, attitudes, and self-efficacy. Sessions were further enhanced through interactive and diverse learning opportunities, including case studies, video analyses, targeted small group activities, resource explorations, and hands-on practice with various strategies to increase usability and self-efficacy with implementation in classrooms.

Table 2.

Topic content summary.

Sessions 3 and 4 consisted of classroom observations and individualized, immediate feedback sessions for select participants. These observations were part of the short-term TA model, in which a 25–40 min observation was held. Inclusion facilitators utilized content-specific observation tools to gather an understanding of each participant’s implementation of best practices around the chosen topic. The data were then utilized to provide immediate feedback and additional resources and strategies and identify areas for improvement with individualized goals for continued implementation.

Session 5 was a wrap-up session that typically lasted for 60 to 90 min. During this session, inclusion facilitators reviewed key concepts and best practices and ways in which educators can continue to utilize strategies and resources beyond the short-term TA support. Session 5 also consisted of administering the post-assessment and assisting participants with setting goals for continued growth.

2.4. Measures

As part of the short-term TA support, participants completed pre- and post-assessments at the beginning and end of the support sessions. Google Forms were used during Sessions 2 and 5 to collect pre- and post-assessment data. The pre- and post-assessments consisted of 15 multiple-choice questions to measure content knowledge, six 6-point Likert scale items to measure attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and six 6-point Likert scale items to capture self-efficacy.

Content knowledge items assessed understanding of legal codes, definitions, historical foundations, and practical applications related to each topic area. Content knowledge scores were calculated by summing the number of correct responses and dividing by the total number of items. Sample items from across topic areas included “What statement best describes co-teaching?”, What is the difference between differentiation and accommodations/modifications?”, What do instructional accommodations include?”, and “According to Administrative Code, who has instructional responsibility for students with IEPs in a co-teaching setting?”. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the internal consistency of content knowledge items across topic areas. Results indicate acceptable reliability for most topics (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011); however, some topics demonstrated lower internal consistency. Specifically, alpha coefficients for co-teaching, differentiation, accommodations and modification, inclusive culture, and Inclusion 101 were 0.69, 0.40, 0.53, 0.77, and 0.67, respectively. The lower reliability observed for the content knowledge measures of differentiation and accommodations and modifications suggests potential limitations, which may be attributed to the small number of items measuring the construct or to the limited sample size from which the analysis was conducted (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Additionally, participants’ content knowledge of a particular topic might be difficult to measure because this type of construct is often heterogeneous (Edelsbrunner et al., 2025). As a result, findings related to these topics should be interpreted with caution, and the measures for differentiation and accommodations and modifications should be further analyzed using psychometric methods and adjusted accordingly to increase internal consistency.

Attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion items assessed educators’ perceptions and ideas related to the who, what, and where of inclusive education. Participants rated their agreement with each statement on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). Total attitudes and beliefs scores were calculated by summing all items. Sample items included “All students with disabilities should be included in general education classrooms for most of the day.”, “Students with disabilities can positively contribute to general education classes.”, and “Students without disabilities can benefit when students with disabilities, including those with significant disabilities, are included in the general education classroom.” All items related to attitudes and beliefs were the same across topic areas. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for the attitudes and beliefs items and suggested acceptable to excellent reliability (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). The alpha coefficients for co-teaching, differentiation, accommodations and modification, inclusive culture, and Inclusion 101 were 0.83, 0.90, 0.76, 0.78, and 0.71, respectively.

Self-efficacy items assessed educators’ comfort and competence with the selected topic for short-term professional development. Participants rated their agreement with each statement provided on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Total self-efficacy scores were calculated by summing all items. Sample items included “I can make instructional and curriculum accommodations and modifications for children with disabilities.”, “I am confident I have the skills to make a difference in the lives of students who have a disability.”, and “I am adequately prepared to deliver instruction to a wide variety of learners using the general education curriculum as a base for instruction.” Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for the self-efficacy items and suggested excellent reliability (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). The alpha coefficients for co-teaching, differentiation, accommodations and modification, inclusive culture, and inclusion 101 were 0.95, 0.94, 0.88, 0.91, and 0.91, respectively.

2.5. Data Preparation

The research team analyzed all data for missing values, outliers, and violations of key assumptions (i.e., normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity). Due to school-based scheduling constraints and barriers, participant availability and attendance varied across sessions. As such, there was a larger-than-expected percentage of missing data on pre- and post-assessments. Across pre- and post-assessments for all short-term TA topics and constructs, missing data ranged from 9.3% to 60.5%. Further analyses of missing data indicate that all data were missing completely at random, as determined by multiple, non-statistically significant Little’s MCAR tests across topic areas and constructs. In order to maintain sample sizes, expectation maximization (EM) was used to impute missing values (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). This approach allowed the research team to maximize statistical power while minimizing bias, which is consistent with best practices for handling data that are missing completely at random (Enders, 2022). Furthermore, no significant univariate or multivariate outliers or violations of assumptions were revealed after extensive analyses.

2.6. Analytical Approach

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were computed for all variables. Due to the hierarchical nature of the data (i.e., participants nested within schools) and the smaller sample sizes across topic areas, we examined intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and conducted power analyses, respectively, to help guide the analytical approach (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). All ICC values indicated minimal between-school variability, suggesting that clustering did not substantially contribute to the total variance in outcomes. Additionally, power analyses reveal that sample sizes were insufficient to reliably estimate multilevel models. As a result, in order to examine changes in participant scores from pre- to post-assessment across all constructs, including content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy, a series of dependent t-tests were conducted. Dependent t-tests evaluate whether the mean difference between paired observations is statistically significant. This statistical approach is appropriate for analyzing pre- and post-assessment data from the same participants, particularly when there are no significant differences in pre-assessment data between groups and when low ICC values suggest that clustering does not contribute significantly to the outcome (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019; Warner, 2012). All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 25.0.

3. Results

Our research team investigated changes in content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy from pre- to post-assessment. The primary research question was as follows: What impact did a short-term TA model of professional development in inclusive education have on participants’ content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about inclusion, and self-efficacy in implementing best practices? To address this critical question, we analyzed data separately by topic area, as assessment data were tailored to specific content areas. The descriptive statistics and results of dependent t-test analyses for each topic of support by construct are provided below.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize performance across content areas and constructs, including content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, and self-efficacy with regard to best practices. Table 3 presents the number of schools per topic area, the number of participants, as well as the mean scores, standard deviations, minimum scores, and maximum scores for all pre- and post-assessment data across constructs. Overall, mean scores on content knowledge post-assessments were higher than on pre-assessments, suggesting positive growth. However, changes in attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion and self-efficacy varied across topics, with some areas showing increases, while others demonstrated decreases from pre- to post-assessment. The results of dependent samples t-tests are presented in the following section.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of pre- and post-assessments of content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy by topic.

3.2. Results by Topic

3.2.1. Co-Teaching

In order to examine whether a short-term TA professional development model impacted participant content knowledge related to co-teaching best practices, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy, a dependent samples t-test was conducted to compare pre- and post-assessment scores of each construct. With regard to co-teaching content knowledge, the dependent samples t-test revealed a statistically significant increase in content knowledge with a large effect size (t(61) = 6.03, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.74). However, no statistically significant change was observed on measures of attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion (t(61) = 1.28, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.18), despite higher post-assessment scores. Dependent t-test analysis of pre- and post-assessments of self–efficacy indicated a statistically significant increase with a small effect size (t(61) = 2.49, p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.28). Overall, results suggest that the short-term TA model of professional development with regard to co-teaching had a positive impact on participants’ content knowledge and a modest impact on self-efficacy. However, the short-term TA support did not result in significant changes in attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion.

3.2.2. Differentiation

To evaluate changes from pre- to post-assessment in content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy related to differentiation, dependent samples t-tests were utilized. There were no statistically significant changes in content knowledge (t(70) = 1.39, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.17), attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion (t(70) = 1.25, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.12), or self-efficacy (t(70) = −1.33, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.12). Results indicate that, for differentiation, the short-term TA professional development model did not lead to statistically significant improvements or declines in any measured outcomes. Any observed changes detected through effect size analyses were small, indicating that changes were minimal in magnitude. Several factors may have contributed to the lack of statistical significance, including measurement limitations, insufficient power, or possible ceiling effects, particularly for the measurement of content knowledge. The sample size might have been too small to detect differences, and baseline scores across constructs were relatively high, leaving little potential for significant growth.

3.2.3. Inclusion 101

In order to analyze pre- and post-assessments in content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy related to Inclusion 101, dependent samples t-tests were conducted. Results indicate that the short-term TA professional development model did not yield statistically significant changes in content knowledge (t(42) = −0.22, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.03), attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion (t(42) = −1.28, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.26), and self-efficacy (t(42) = −1.25, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.23). The short-term TA professional model on Inclusion 101 did not lead to statistically significant improvements in content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, or self-efficacy. There are several factors that may have impacted the results, including sample size, missing data imputation, and the nature of constructs under examination. The smaller sample size reduced statistical power, making it more difficult to detect significance. This challenge was further exacerbated by a high percentage of missing data, which may have resulted in an underestimation of standard errors. Furthermore, as observed in other topic areas, changing attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, as well as enhancing self-efficacy, may require more intensive interventions to yield change.

3.2.4. Inclusive Culture

In order to examine whether a short-term professional development model impacted content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy with regard to the topic of Building an Inclusive Culture, dependent samples t-tests were conducted to compare the pre- and post-assessment scores for each construct. In terms of content knowledge, results indicate a statistically significant increase in content knowledge with a small to moderate effect size (t(46) = 10.13, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.30). Additionally, a statistically significant change was observed on measures of attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion (t(46) = 4.12, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.84), indicating that attitudes and beliefs were influenced in a positive manner after participating in the short-term TA professional development on inclusive school cultures. Furthermore, results indicate that there was a statistically significant increase in self-efficacy (t(46) = 2.56, p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.38). The results overall suggest that this particular short-term TA model of professional development geared toward cultivating an inclusive school culture improved participant content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy. This topic was the only one to display statistical significance across all constructs, which likely resulted from the stronger emphasis on attitudes and beliefs during short-term TA package delivery.

3.2.5. Accommodations and Modifications

To evaluate the impact of a short-term TA professional development model on content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy related to accommodations and modifications, dependent samples t-tests were used to compare pre- and post-assessment scores for each construct. The analyses revealed a statistically significant increase in content knowledge with a large effect size (t(43) = 11.52, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.29). However, no statistically significant differences were observed on measures of attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion (t(43) = 1.86, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.35) or self-efficacy (t(43) = 1.64, p > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.44), despite moderate effect sizes. Overall, results suggest that the short-term model of professional development for accommodations and modifications had a positive impact on content knowledge; however, given the lower reliability detected for this measurement tool, results should be interpreted with caution. Results did not indicate an impact on attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion or self-efficacy.

4. Discussion

Building on previous research (Montalbano et al., 2024), our team aimed to examine the effectiveness of short-term TA professional development in best practices in inclusive education across 15 schools. While a variety of short-term TA packages were offered, school administrators selected specific packages for their school with guidance from project inclusion facilitators. The selected topics included Co-Teaching, Differentiation to Support Inclusive Education, Inclusion 101, Building an Inclusive School Culture, and Operationalizing Modifications and Accommodations. Our research team examined the impact of the short-term TA on participants through dependent samples t-test analysis of pre- and post-assessment data, focusing on content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, and self-efficacy. The results reveal that content knowledge demonstrated the largest positive change across all short-term TA training.

The results from this study indicate the effectiveness of short-term TA primarily in increasing content knowledge of best practices in the Co-Teaching package. While there was a statistically significant increase in content knowledge for co-teaching, there was also a modest impact on self-efficacy in this area. Growing in content knowledge from the training offered is beneficial, as this helps build self-efficacy. While results on the post-assessment demonstrated higher scores in regard to attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, there was no statistically significant increase. This is not surprising given that effectively implementing co-teaching takes time to develop co-teaching relationships, requires time for collaboration, and is dependent on attitudes toward inclusion of the teachers in the co-teaching team (Jortveit & Kovač, 2022).

Short-term TA professional development packages that focused on instructional strategies seemed to follow a similar trend in the results. There was a lack of statistically significant increases in all areas in the Differentiation to Support Inclusive Education package and the Inclusion 101 package. These areas appear to require more intensive professional development over a longer duration. As indicated in the literature, for professional development to create meaningful change, there needs to be a sustained focus over time (Desimone, 2009). The results support this, as the short-term TA did not appear to increase content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward inclusion, or self-efficacy in these areas. The focus of these packages was more instructionally focused and not as content-heavy. As such, these findings indicate that more intensive strategies are needed when related to instructional strategies and implementation. Observations, modeling, and coaching can offer more in-depth support to assist teachers in growing in this area and in their self-efficacy to implement inclusive best practices (Hammond & Moore, 2018; Yang et al., 2022). These would afford teachers more in-depth support and training to implement these differentiated practices for inclusion.

Results of the Operationalizing Modifications and Accommodations package followed this trend. This training primarily focused on implementing IEP modifications and accommodations in the classroom. This is an area of struggle identified by many teachers (Mcglynn & Kelly, 2019), so more in-depth training is warranted. As indicated in other results for classroom-specific implementation training, short-term TA falls short of impactful professional growth. There was no statistically significant change in attitudes and beliefs and self-efficacy in this area. This further supports the finding that more intensive, focused, and enduring professional development, such as coaching, is needed in these areas. It is important to note that a pivotal aspect of this package was the training on the differences between modifications and accommodations. This did have an impact on participants, as results indicate a statistically significant increase in content knowledge. This finding continues to demonstrate the strength of short-term TA in increasing content knowledge but the limited scope of change when it comes to classroom-specific implementation.

Contrary to the trends discussed above, short-term TA proved to be an effective model in regard to building an inclusive school culture. Statistically significant increases were identified in all areas (content knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, and self-efficacy) of the Building an Inclusive School Culture package. The focus of this package allowed participants to dive into actionable steps toward building and supporting an inclusive school culture. These actionable steps, coupled with a content-heavy approach to building an inclusive culture, increased participants’ attitudes and beliefs and self-efficacy in building a school culture that embraces inclusion. Within these training sessions, there was also a strong emphasis on attitudes and beliefs that are necessary to change school culture. This appears to have increased participants’ self-efficacy and content knowledge as a result.

Similar to previous findings with different samples (Montalbano et al., 2024), the findings of this study reveal that the short-term TA model for professional development is beneficial for use in schools. The results of using short-term TA reveal that participants experienced significant gains in their knowledge, which is a major aspect of utilizing and implementing best practices (Pit-ten Cate et al., 2018). When the emphasis is placed on content knowledge and attitudes and beliefs, there is an increase in self-efficacy. The results indicate that while short-term TA is a good starting point for introducing classroom instructional strategies, it is not a strong model for helping teachers grow in these areas for implementation. More impactful and meaningful change toward strategies for best practices in the classroom requires more intensive professional development, such as coaching, over a longer period of time. Coupling short-term TA with other training models, such as modeling or coaching, for the classroom implementation of strategies, could lead to more impactful change in this area; however, short-term TA does yield benefits toward building an inclusive culture and introducing new content knowledge. This is important as new knowledge, when cultivated, can lead to improved self-efficacy and meaningful change.

Limitations and Future Research

This study consisted of an adequate sample size; however, the participants were representative of one state in the northeastern United States. Due to this regionalization of the participants, the generalizability of the results is limited. Future studies can examine the use of short-term TA professional development across other regions to obtain a wider representative sample. It is important to note that local policies and school leaders can impact the willingness of schools to take part in professional development for inclusive education. These factors can impact future results of wider samples, as those more willing to embrace inclusion can be overly represented. In addition, several packages had larger percentages of missing data either pre- or post-assessment. While missing data were determined to be missing completely at random and, thus, EM was used to impute missing values, this impacted potential variability and might have influenced results accordingly. Thus, continued problem-solving around ways to limit missing data, including providing additional opportunities for participants to complete assessments, is warranted in future similar studies.

Another limitation of this study is that self-report measures were used to examine growth across topic areas and constructs. While this is an acceptable methodology for gauging changes in content knowledge, it might not always be ideal for attitudes and beliefs or self-efficacy measurement, as participants might respond in ways they believe are socially acceptable rather than providing truthful responses (Tourangeau et al., 2000). Future studies might utilize this assessment approach, in conjunction with observable, objective measures, such as observations or performance measures over time. While observations were conducted for immediate feedback, having a series of observations over a longer period of time might prove beneficial to ensure the continuation and improvement of implementation. This would help provide an additional lens to measure the effectiveness of the short-term TA in practice.

Finally, future studies can examine the effectiveness of short-term TA in a longitudinal manner to determine if the participants continued using best practices in inclusive education after the training concluded. It would be noteworthy to determine whether the short-term TA created meaningful change that lasted over time, or if participants returned to prior approaches and practices. The use of coaching as a supplement to the short-term TA model, coupled with longitudinal data collection, could help examine the effectiveness of these models for professional development more deeply.

5. Conclusions

Studies have consistently shown that schools encounter challenges in implementing inclusive practices, with teacher training frequently cited as a key factor contributing to these difficulties (DeMatthews & Mawhinney, 2014; Kart & Kart, 2021). This study suggests that short-term TA can assist in increasing content knowledge of best practices in inclusive education. Attitudes and beliefs in inclusive education were positively impacted through short-term TA that focused heavily on building an inclusive school culture. The growth demonstrated by participants across the various areas of content knowledge toward inclusive education reveals that this can be a good starting point for school districts to employ to help implement inclusive practices in schools. Building this background knowledge is important, and it can lead to more significant growth with additional training and support. However, more intensive training with longer durations and coaching seems to be more beneficial creating meaningful change in regard to instructional strategies for classroom use. As schools look to overcome challenges for the implementation of inclusive practices, short-term TA can serve as a beneficial method for providing professional learning opportunities and increasing content knowledge of inclusive best practices in education.

Author Contributions

J.A.H.—project administration, conceptualization, methodology, writing, reviewing, and editing; C.M.—conceptualization, methodology, formal analyses, writing, reviewing, and editing; J.C.—writing, reviewing, and editing; J.M.—writing, reviewing, references; M.K.—writing, reviewing, editing, and references; B.J.K.—methodology, formal analyses; J.N.-T.—methodology, formal analyses, and reviewing; S.J.—inclusion facilitator, conceptualization, writing, reviewing, and editing; J.L.—inclusion facilitator, conceptualization, writing, reviewing, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was deemed exempt from IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

The initial data collection occurred as part of standard operating procedures for the non-profit agency as part of their project evaluation process for non-research purposes. This research team conducted a secondary analysis of the data. Thus, the secondary analysis was not subject to IRB approval, as it occurred after all data were collected.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available by request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the New Jersey Department of Education and All In for Inclusive Education.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(4), 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Batsche, G. (2014). Multi-tiered systems of supports for inclusive schools. In J. McLeskey, N. L. Waldron, F. Spooner, & B. Algozzine (Eds.), Handbook of effective inclusive schools (pp. 183–196). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley, B., & Bettini, E. (2019). Special education teacher attrition and retention: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 697–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S. (2018). Evaluating the impact of professional development. RELC Journal, 49(2), 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundock, K., Rolf, K., Hornberger, A., & Halliday, C. (2023). Improving access to general education via co-teaching in secondary mathematics classrooms: An evaluation of Utah’s professional development initiative. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 42(2), 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canter, L. L. S., King, L. H., Williams, J. B., Metcalf, D., & Potts, K. R. M. (2017). Evaluating pedagogy and practice of universal design for learning in public schools. Exceptionality Education International, 27(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Capp, M. J. (2017). The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A meta-analysis of literature between 2013 and 2016. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(8), 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. M., Murphy, H. R., Frisby, M. B., & Robinson, J. (2023). The relationship between special education placement and high school outcomes. The Journal of Special Education, 57(1), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colson, T., Xiang, Y., & Smothers, M. (2021). How professional development in co-teaching impacts self-efficacy among rural high school teachers. The Rural Educator, 42(1), 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, J., & DeMatthews, D. E. (2021). Failure is not final: Principals’ perspectives on creating inclusive schools for students with disabilities. Journal of Educational Administration, 59(4), 514–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S. L., Smith, S. J., & Frey, B. B. (2022). Professional development with universal design for learning: Supporting teachers as learners to increase the implementation of UDL. Professional Development in Education, 48(1), 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, C., & Bayrakcı, M. (2019). Teacher professional development models for effective teaching and learning in schools. The Online Journal of Quality in Higher Education, 6(1), 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- DeMatthews, D., Billingsley, B., McLeskey, J., & Sharma, U. (2020). Principal leadership for students with disabilities in effective inclusive schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(5), 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatthews, D., & Mawhinney, H. (2014). Social justice leadership and inclusion: Exploring challenges in an urban district struggling to address inequities. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50, 844–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, J. L., Lüke, T., Graf, E., Tran, U. S., & Götz, T. (2023). Does professional development effectively support the implementation of inclusive education? A meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 35, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuFour, R. (2004). What is a “professional learning community”? Educational Leadership, 61(8), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Edelsbrunner, P. A., Simonsmeier, B. A., & Schneider, M. (2025). The Cronbach’s alpha of domain-specific knowledge tests before and after learning: A meta-analysis of published studies. Educational Psychology Review, 37(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlert, M., & Souvignier, E. (2023). Effective professional development in implementation processes–the teachers’ view. Teaching and Teacher Education, 134(4), 104329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C. K. (2022). Applied missing data analysis (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, K., Gonzalez, M., & Cooper, C. (2020). Outcomes of inclusive versus separate placements: A matched pairs comparison study. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 45(4), 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M. C., & Jones-Goods, K. M. (2016). Identifying and correcting barriers to successful inclusive practices: A literature review. Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, L., & Moore, W. M. (2018). Teachers taking up explicit instruction: The impact of a professional development and directive instructional coaching model. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 43(7), 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Q., & Rabren, K. (2009). An examination of co-teaching: Perspectives and efficacy indicators. Remedial and Special Education, 30(5), 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2018). Leading schools as learning organizations. School Leadership & Management, 38(4), 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, M., & Lelinge, B. (2021). Teachers’ collaborative professional development for inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(5), 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400. (2004). Available online: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/2021-individuals-with-disabilities-education-act-annual-report-to-congress/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Jones, N., & Winters, M. A. (2023). Are two teachers better than one? The effect of co-teaching on students with and without disabilities. Education Next, 23(1), 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jortveit, M., & Kovač, V. B. (2022). Co-teaching that works: Special and general educators’ perspectives on collaboration. Teaching Education, 33(3), 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kart, A., & Kart, M. (2021). Academic and social effects of inclusion of students without disabilities: A review of the literature. Education Sciences, 11(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J. M., Burke, M. D., & Anastasiou, D. (2023). Hard LRE choices in the era of inclusion: Rights and their implications. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 34(1), 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. M. (2016). How does professional development improve teaching? Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 945–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., Wehmeyer, M. L., Soukup, J. H., & Palmer, S. B. (2010). Impact of curriculum modifications on access to the general education curriculum for students with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 76(2), 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, H. R., & Horn, E. (2021). Definition, context, quality: Current issues in research examining high-quality inclusive education. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 40(4), 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcglynn, K., & Kelly, J. (2019). Adaptations, modifications, and accommodations. Science Scope, 43(3), 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeskey, J., Barringer, M.-D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., Lewis, T., Maheady, L., Rodriguez, J., Scheeler, M. C., Winn, J., & Ziegler, D. (2017). High-leverage practices in special education. Council for Exceptional Children & CEEDAR Center. [Google Scholar]

- Montalbano, C., Lang, J., Coviello, J. C., McQueston, J. A., Hogan, J. A., Nissley-Tsiopinis, J., Ciotoli, F., & Buglione, F. (2024). Inclusive education virtual professional development: School-Based professionals’ knowledge of best practices. Education Sciences, 14(9), 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pit-ten Cate, I. M., Markova, M., Krischler, M., & Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2018). Promoting inclusive education: The role of teachers’ competence and attitudes. Insights into Learning Disabilities, 15(1), 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Postholm, M. B. (2018). Teachers’ professional development in school: A review study. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1522781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancar, R., Atal, D., & Deryakulu, D. (2021). A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 101(2), 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, V. C., Jillani, Z., Malpert, A., Kolodny-Goetz, J., & Wandersman, A. (2022). A scoping review of the evaluation and effectiveness of technical assistance. Implementation Science Communications, 3(1), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruggs, T. E., Mastropieri, M. A., & McDuffie, K. A. (2007). Co-teaching in inclusive classrooms: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Exceptional Children, 73, 392–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakman, K., Wogan, D., Rodriguez, S., Boyce, J., & Shaver, D. (2020). Continuous improvement in education: A toolkit for schools and districts (REL 2021–014); U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands.

- Sims, S., Fletcher-Wood, H., O’Mara-Eves, A., Cottingham, S., Stansfield, C., Goodrich, J., Van Herwegen, J., & Anders, J. (2023). Effective teacher professional development: New theory and a meta-analytic test. Review of Educational Research, 95(2), 213–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinth, Y. (2018). Journal of occupational therapy: Schools and early intervention a special issue on transition. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 11(2), 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. (2025). Building and sustaining inclusive educational practices. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/media/document/inclusive-practices-guidance-109436.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Warner, R. M. (2012). Applied statistics: From bivariate through multivariate techniques (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K. E., & Greiner, F. (2019). Development of pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and attitudes towards inclusive education through first teaching experiences. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 19, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, S., & Hardy, I. (2023). Teacher self-efficacy, inclusion and professional development practices: Cultivating a learning environment for all. Professional Development in Education, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, S., Sharma, U., Subban, P., & Hitches, E. (2022). Teacher self-efficacy and inclusive education practices: Rethinking teachers’ engagement with inclusive practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117(1), 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., Huang, R., Su, Y., Zhu, J., Hsieh, W. Y., & Li, H. (2022). Coaching early childhood teachers: A systematic review of its effects on teacher instruction and child development. Review of Education, 10(1), e3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).