1. Introduction

Students with intellectual and developmental disabilities often exhibit challenging behaviors that interfere with learning. In a systematic review of prevalence studies,

Simó-Pinatella et al. (

2019) found that overall prevalence rates of challenging behavior ranged from 48% to 60% of school-age children with intellectual disabilities and 90% of children with autism. Challenging behavior varies in frequency and severity depending on individual learners and environmental circumstances. Challenging behavior is typically defined as verbal or physical aggression toward others, self-injurious behavior, property destruction, disruptive behavior, and/or refusal to participate in essential daily activities (

Thompson et al., 2022).

Often, these challenging behaviors impact students’ ability to form relationships (

Slane & Lieberman-Betz, 2021), experience social interactions (

Nankervis et al., 2019), and participate in inclusive settings (

Lory et al., 2020). Failure to effectively address challenging behaviors—which may be chronic over time—can lead to academic failure, exclusion, school suspensions or expulsions, and family stress (

Thompson et al., 2022). Children with challenging behaviors often require intensive levels of support and instruction by skilled teachers.

Fortunately, teachers can learn skills to effectively address their students’ challenging behaviors. These skills can be grouped into two general categories: planning and instruction. When planning for students with challenging behaviors, teachers could involve the student’s family and other professionals with direct knowledge of the student (

L. Hogan & Bigby, 2024). In addition, teachers could attempt to understand the causes of problem behaviors (

Farmer et al., 2014;

Stoesz et al., 2014). Ultimately, the planning may focus on eliminating triggers to problem behaviors while incorporating conditions that reduce the occurrence of problem behaviors (

Westing, 2015). During instruction, teachers can pay attention to and modify aspects of the instructional and non-instructional tasks based on their contribution to the occurrence of problem behavior (

Farmer et al., 2014). Teachers can incorporate choice, predictability, and non-contingent attention (

Sobeck & Reister, 2020), and adapt instruction as needed for each student (

Ruppar et al., 2017). Training teachers to use the Universal Protocol can help teachers acquire skills for both planning and instruction. This study examines the use of the Universal Protocol within the context of a student–teacher dyad. The Universal Protocol was chosen because, based on teacher report, some of the traditional methods she used to address challenging behavior such as the use of token boards, wait time, offering choices, and first next schedules were proving ineffective for the student.

1.1. Universal Protocol

The Universal Protocol is a set of guidelines developed to decrease challenging behavior and the need for intrusive interventions (

Ruppel & Ingvarsson, 2025). Specifically, the Universal Protocol was designed to increase student motivation, prevent the escalation of challenging behavior, teach students to associate staff with positive experiences, and increase job satisfaction for staff. Furthermore, as a treatment package, the Universal Protocol provides a mechanism for staff to interact with students that allows rapport building, the identification of triggers to challenging behavior, the evaluation of commonly used interventions, and decision making about the intensity of services needed.

The components of the Universal Protocol include establishing positive regard and empathy towards the student, enriching the environment, following the student’s lead, limiting non-essential demands and expectations, reinforcing precursor behavior, and inviting students to work. The following provides a brief description of each of these components.

1.1.1. Establish Positive Regard and Empathy Towards the Student

Demonstrating positive regard and empathy to build a relationship with the student (e.g.,

Amos, 2004;

McLaughlin & Carr, 2005) is one component of the Universal Protocol. This includes having a positive attitude and understanding that challenging behavior serves a purpose for the student and is the result of the student’s reinforcement history, and not a result of a disability. In a school, positive regard might look like greeting a student upon entering a classroom, smiling, and using praise. Other observable examples of positive regard and empathy include making positive statements, making statements that validate a student’s feelings, showing enthusiasm, and displaying a sense of humor (

Ruppar et al., 2017).

1.1.2. Enrich the Environment

Teachers enrich the environment when they provide many reinforcing or rewarding items and activities with frequent positive attention (

Gover et al., 2019,

2022). This includes providing multiple versions or variations of the preferred items or activities. For example, enriching the school environment for a student who likes animals might consist of simultaneously providing small plastic zoo animals, books about animals, pictures of animals, animal videos, and craft activities related to animals.

1.1.3. Follow the Student’s Lead

Teachers follow the student’s lead when they allow them to make choices with respect to activities that they would like to complete, including work demands (

Rajaraman et al., 2023). During the school day, teachers could make sure that the student is provided many opportunities to make choices about activities. Following the student’s lead also occurs when teachers share in the student’s activities rather than just supervise them (

McLaughlin & Carr, 2005).

1.1.4. Limit Non-Essential Demands and Expectations

Limiting non-essential demands requires that staff evaluate which demands are important in the short term and which demands are not. Given that some demands are likely to trigger or escalate problem behaviors, reducing demands may prevent or decrease challenging behavior. For example, essential demands are related to safety, entering and exiting school, and eating lunch (

G. H. Hanley & Ruppel, 2021).

1.1.5. Reinforce Precursor Behavior

Reinforcing precursor behaviors consists of first identifying the behavior(s) that co-occur with or prior to challenging problem behaviors that are not challenging or unsafe (e.g., verbal complaints, groaning or non-dangerous gestures), and second, reinforcing the occurrence of the precursor behaviors with all the identified reinforcers (

Fahmie & Iwata, 2011;

Heath & Smith, 2019;

Warner et al., 2020). For example, in addition to providing just attention, school staff may also provide access to tangibles and remove demands. The purpose of reinforcing precursor behaviors is to minimize the escalation to behaviors to forms that present challenges or safety concerns for both students and staff.

1.1.6. Invite Students to Work

Inviting students to work, like providing choices, occurs when teachers ask students if they would like to work and then defer to the student’s answer. This component is supported by the concept of invitational learning (

Tomlinson, 2002). Invitations can take many forms and respecting the student’s response serves to acknowledge them while communicating unspoken messages such as “I have respect for who you are and who you can become. I want to know you. I have time for you. I try to see things through your eyes. This classroom is ours, not mine” (

Tomlinson, 2002, p. 11).

As a treatment package, the Universal Protocol is made up of several evidence-based components and is currently used in public and private schools, clinics, homes, and residential settings (see ftfbc.com). However, empirical research on the Universal Protocol as a separate, stand-alone training package has not been previously researched. The purpose of this study is to experimentally examine the effects of the Universal Protocol on teacher and student behaviors using an evidence-based training procedure, Behavior Skills Training (BST).

1.2. Behavior Skills Training

Behavior Skills Training (BST) is an evidence-based protocol for training human service personnel (

Parsons et al., 2013). Prior to implementing BST, a skill is selected for training, for example, reliable data collection using partial interval recording. The implementation of BST consists of the following components (

Parsons et al., 2013): First, trainers describe the target skill by defining the exact behaviors needed to perform the skill and the rationale for why the skill is important (e.g., “Proper data collection is important to help make decisions about client progress. To do it accurately, you will need to mark whether a behavior occurred or did not occur during each one-minute interval”). Second, the trainer provides a written description of the target skill (e.g., a checklist with each step of the data collection procedure). Third, the trainer models the skill for the trainee (e.g., the trainer collects data according to the procedure while the trainee watches). Fourth, the trainee performs the skill, and the trainer provides feedback (e.g., the trainee collects data for a short period of time and the data are reviewed by both the trainer and trainee for accuracy and demonstration of the correct data collection procedure). This practice (trainee) and feedback (trainer) cycle is repeated until the trainee can demonstrate the skill and achieves a predetermined mastery criterion (e.g., the trainee collects data with 95% accuracy over four 30 min sessions).

BST has been identified as a successful methodology used to train staff to manage problem behaviors by assessing behaviors, teaching replacement skills, and implementing behavior plans.

Samudre et al. (

2023) used BST to teach fifty preservice teachers to assess problem behaviors by collecting data on antecedent conditions, problem behaviors, and consequences, and then formulate a hypothesis about the function of the problem behavior. The results indicated a statistically significant increase in correct responses in a posttest evaluation after the completion of BST.

Lerman et al. (

2015) taught five adults on the autism spectrum to implement mand training (i.e., making requests) that could serve as replacement behaviors for children who exhibited problem behaviors. The results indicated that behavioral skills training was effective for teaching the adult participants the procedures needed to teach children with autism. BST was also used to teach four female instructional staff to successfully implement behavior plans for children with autism and other developmental disabilities (

A. Hogan et al., 2014). The results indicated that each staff member’s implementation improved as a function of BST.

BST has also been demonstrated to be effective for training special education teachers to implement free operant preference assessments (

Li & Alber-Morgan, 2024); training parents to provide behavioral interventions (

Schaefer & Andzik, 2021); training staff to implement video-based interventions (

Erath et al., 2021); training staff to respond to child-initiated social participation behaviors (

Holt et al., 2024); and teaching staff to implement naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions (

Mrachko et al., 2022).

This study was designed to examine the effects of BST in teaching a special education teacher to implement the Universal Protocol package with a kindergarten student who was diagnosed with autism. The specific research questions are as follows:

What are the effects of Behavior Skills Training of the Universal Protocol on the accuracy of teacher implementation?

What are the effects of teacher delivery of a Universal Protocol treatment package on challenging behavior?

What is the teacher’s opinion of the Universal Protocol intervention?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A special education teacher and a student were the participants in this study. Emily, the teacher, had a master’s degree and five years of teaching experience. Her primary responsibilities included teaching students with moderate-to-intensive needs in a self-contained classroom targeting academic, social/emotional, functional, communication, and life skills.

Sarah, the student participant, was a six-year-old female kindergartener on the autism spectrum. Sarah communicated primarily through gestures, one-word utterances, and an augmentative communication device. Additionally, Sarah received special education services for physical therapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy.

This study was approved by The Ohio State University’s Institutional Review Board. Data collection began after the teacher participant provided signed informed consent and the student participant’s parents provided signed informed consent/permission for their child to participate in this study.

2.2. Setting

This intervention took place in a suburban public school district of a large midwestern city in the following school settings: transition, work, and reward. The transition setting is the drop-off/pick-up area and the hallways leading to Sarah’s classrooms. Observation time in the transition setting began at the drop-off/pick-up area outside the school and ended when Sarah entered one of her classrooms. The materials found in the transition setting included the student’s coat, backpack, and harness that she used when riding the bus. During the study, transition sessions averaged 5.4 min (range: 1.7 min to 20.7 min).

The work setting was a small classroom where Sarah was expected to complete academic work. The observation time in the work setting began when Sarah entered the small classroom and ended when Sarah exited the small classroom. This setting contained a table, two chairs, and a storage area for large toys. The curricular materials used in this study included puzzles, number cards, writing utensils, file folders with matching activities, and other instructional materials. During the study, work sessions averaged 10.0 min (range: 2.3 min to 20.0 min).

The reward setting was in the special education classroom, where Sarah had opportunities to engage in preferred activities. The observation time in the reward setting began when Sarah entered the classroom and ended when Sarah left the classroom to go to recess or when she was asked to begin working with a related service staff member. The classroom contained two chairs, a large table, and two dividers that were used to separate the play area from the rest of the classroom. Materials in this setting included markers, stickers, crayons, drawing paper, Play-Doh, small plastic people and animals, a dollhouse, and stuffed animals. During the study, reward sessions averaged 11.0 min (range: 1.4 min to 33.9 min).

During all sessions, the teacher, Emily, wore a GO PRO 10 camera affixed to a vest mount to video record all sessions.

2.3. Definition and Measurement of Dependent Variables

There were four dependent variables in this study. The percentage of Universal Protocol components was the dependent variable to assess teacher performance. For the student, the dependent variables were the rate of challenging behaviors, rate of precursor behaviors, and percentage of time spent engaged with academic tasks during the work setting. For each dependent variable, video recordings were reviewed using the descriptions in

Table 1.

2.3.1. Percentage of Universal Protocol Components Demonstrated by the Teacher

The teacher’s behavior was scored according to each component as either demonstrated, absent, or no opportunity to demonstrate. The percentage of components completed was calculated by dividing the number of components demonstrated by the total number of components for which there was opportunity to demonstrate and multiplying by 100.

2.3.2. Student Percentage of Intervals with Challenging Behaviors

Challenging behaviors included hitting, kicking, throwing objects, biting or attempting to bite, or pounding on a hard surface with a closed fist. These behaviors were recorded using a 1 s whole-interval method. Then, the percentage of occurrence was calculated by dividing the number of intervals in which the challenging behaviors occurred by the total number of intervals for the session and multiplying by 100.

2.3.3. Student Percentage of Intervals with Precursors Behaviors

Precursor behaviors included crying, dropping to the floor, loud vocalizations, waving at or pushing materials away, and turning away from the teacher. These behaviors were recorded using a 1 s whole-interval method. Then, the percentage of occurrence was calculated by dividing the number of intervals in which the precursor behaviors occurred by the total number of intervals for the session and multiplying by 100.

2.3.4. Percentage of Time Engaged in Work Tasks

The percentage of time engaged was the number of seconds that the student was engaged in academic tasks, such as number or letter puzzles. The seconds of engagement were divided by the total number of seconds in the session to determine the percentage of engagement time.

2.4. Experimental Design

A multiple-baseline across settings design was used to examine the effects of BST of the Universal Protocol on teacher performance and on student behaviors. Baseline data were collected until the data were stable in each setting. Then, the intervention was applied in a staggered format to the reward setting, then the work setting, and then the transition setting.

Table 1 shows the Universal Protocol skills that were targeted for each setting.

2.4.1. Baseline

During baseline, the student (Sarah) followed her daily schedule, and data were collected on the rate of challenging behaviors, rate of precursor behaviors, and percentage of time engaged in work tasks. Data were also collected on the percentage of Universal Protocol components the teacher (Emily) demonstrated. Upon arrival at school, Sarah transitioned from the transportation drop-off area into the work setting, where she completed various activities (e.g., puzzles, matching activities). When Sarah finished her assigned work, she engaged with preferred activities in the reward setting.

2.4.2. Intervention

This intervention was implemented in three phases: (1) parent interview, (2) initial experimenter observations in each setting, and (3) using BST to train the teacher.

Phase 1

The teacher and student’s parents participated in a virtual meeting in which the experimenter conducted a parent interview (

G. P. Hanley et al., 2014). The interview meeting lasted approximately one hour and was conducted to identify the student’s strengths, preferences and the environments and activities in which the problem behaviors rarely occurred. In addition, working definitions of the topography of the student’s challenging behaviors and the precursor behaviors were identified. Finally, the common triggers, activities, and environments that reliably produced problem behaviors were identified. The student’s challenging behaviors included crying, dropping to the floor, making vocalizations that were louder than typical voice volume, waving at or pushing materials away, and turning away from the teacher. In addition, during the transitions into school in which parents dropped her off, her mom often carried her into school to prevent elopement and avoid any other forms of non-cooperation while the student was walking into school.

The common triggers, activities, and environments that reliably produced problem behaviors were identified as being asked to complete work activities, being told “no,” and when preferred activities came to an end.

Phase 2

Two observations of the transition setting, work setting, and reward setting were conducted by the experimenter to determine the precise Universal Protocol skills to be taught to the teacher during the BST session for each setting. During these observations, several key features were noted. One, the teacher was inadvertently placing multiple demands in the form of requesting expressive communication responses from the student in the reward setting. Two, upon transitioning into school, the student entered the work setting and was immediately required to complete multiple tasks. The tasks contained both matching and identification requests as well as the expectation that the student engage with her device to communicate expressively. Finally, as previously noted, during the transition into school, the student was often carried by her mother or was provided minimal choices or opportunities to earn known reinforcers for completing the transition.

Phase 3

BST was used to teach the specific components of the Universal Protocol treatment package for each setting (see

Table 1). The reward setting was targeted first, and the experimenter met with the teacher during her plan period for approximately 30 min to explain the baseline observations and rationale for the implementation of each behavior. Next, the teacher was given a written explanation of the components to implement. Then, she engaged in role plays with the experimenter to practice each component. The role plays continued until the teacher could demonstrate each behavior in the Universal Protocol accurately twice. Finally, the teacher began the intervention on a daily basis with the student in the reward setting. The introduction of the behaviors using BST using the same procedure was repeated for the work setting and then the transition setting.

2.4.3. Interobserver Agreement

Two PhD students in applied behavior analysis were trained individually through video conferencing to collect IOA data. Training consisted of observing and scoring video examples of teacher and student behaviors and receiving feedback from the experimenter. IOA data were collected on 30% to 31% of the sessions across experimental conditions and settings. IOA for the teacher’s demonstration of the components of the Universal Protocol procedure was calculated using the interval-by-interval IOA method by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. IOA for the student’s frequency of challenging behaviors and precursor behaviors was calculated using the total count IOA method by dividing the smaller total frequency by the larger total frequency and multiplying by 100. For engaged time in work, IOA was calculated using the total count IOA method by dividing the smaller duration by the larger duration and multiplying by 100.

3. Results

This section presents the results of each dependent variable, social validity, and interobserver agreement.

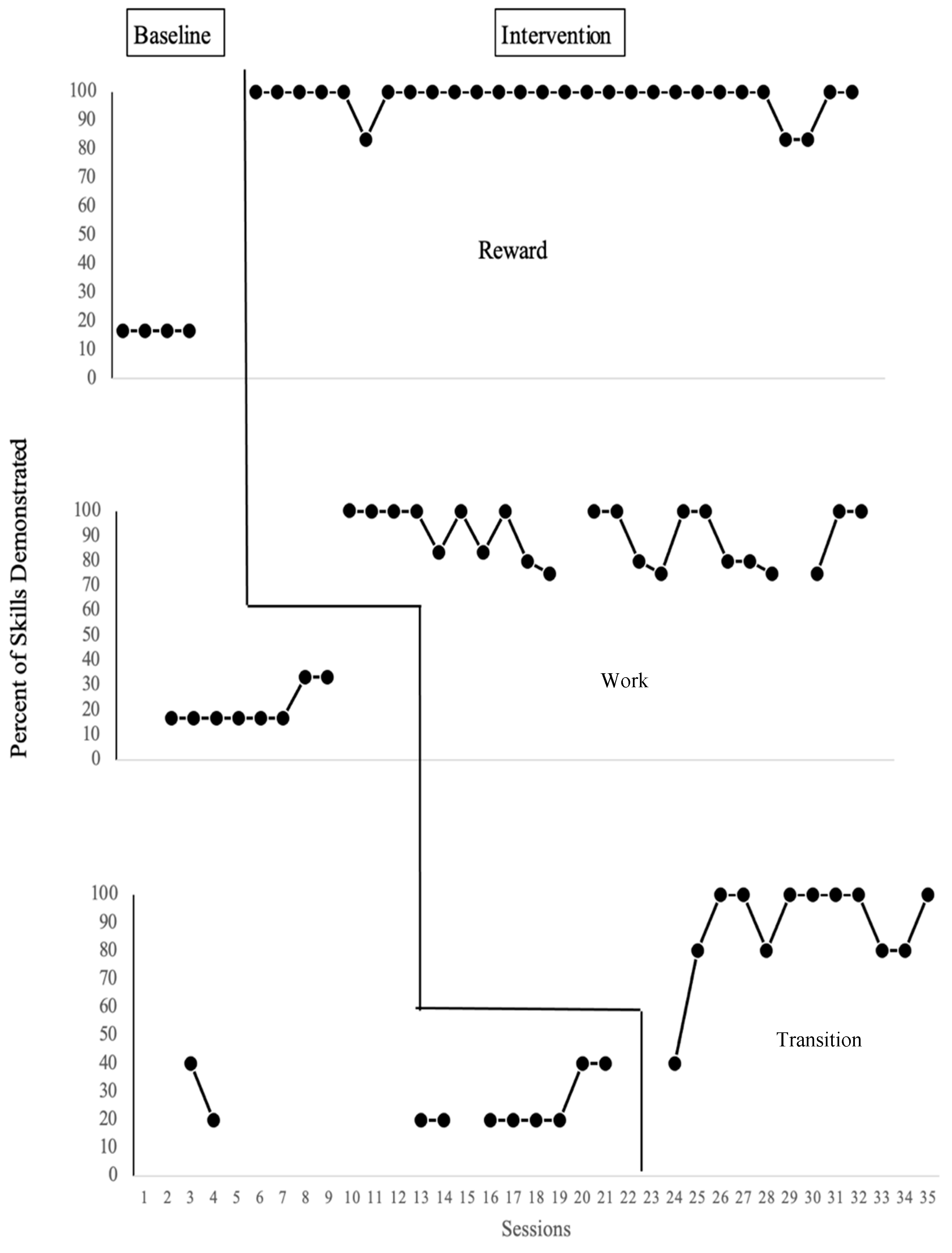

3.1. Universal Protocol Components Demonstrated by the Teacher

Figure 1 shows the mean percentage of Universal Protocol components completed by the teacher in each setting. During baseline, data were stable, ranging from 16% to 40%. After intervention, there was an immediate and substantial increase to 100% in the reward and work setting, and a more gradual increase for the transition setting. The data were most stable after intervention in the reward setting (80% to 100%) and most variable in the transition setting (ranging from 40% to 100%).

3.2. Percentage of Intervals with Student Precursor and Challenging Behaviors

Figure 2 shows the percentage of 1 s intervals in which the student engaged in challenging and precursor behaviors using a multiple-baseline across settings graph. For challenging behaviors, the average percentage of occurrence in baseline across all settings was 0.42% (range: 0.06% to 0.71%). After intervention, the average percentage of occurrence of challenging behaviors across all settings dropped to 0.06% (range: 0.02% to 0.10%). This represents an average 78.2% decrease in the percentage of intervals of challenging behaviors. For precursor behaviors, the average percentage of occurrence in baseline across all settings was 8.6% (range: 6.2% to 12.4%). After intervention, the average percentage of occurrence of precursor behaviors across settings dropped to 1.9% (range: 0.43% to 3.8%). This represents an average 80.3% decrease in the percentage of intervals of precursor behaviors.

3.3. Percentage of Time Engaged in Work Tasks

During the 19 intervention sessions in the work setting, the average percentage of time that the student engaged in academic tasks was 36.5% (range: 0% to 92%). In addition, the student chose to work for at least 25% of the session in 11 out of 19 sessions. This engagement represents the percentage of the session that the student chose to work when invited. She had the option to refuse work and return to preferred activities immediately. It should be noted that these data do not have a comparison in the work baseline sessions because the student was not invited to work or given the opportunity to refuse work. Work demands were placed and continued until the work was completed.

3.4. Social Validity

After the last day of data collection, the teacher completed a nine-item opinion questionnaire (

G. P. Hanley, 2022). The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first part presented the teacher with questions to answer using a Likert scale (0—Not Likely to 4—Very Likely) related to the ease of and future likelihood of implementation. In the second part, the teacher used a Likert scale (0—No Sessions to 5—Almost all Sessions) to rate the student’s behavior. Please see

Table 2 for the results.

After completing the questionnaire, the teacher was asked to identify the best part of the procedures; she indicated “seeing the success that the student had and how much happier she is at school”.

3.5. Interobserver Agreement

The mean interobserver agreement for the teacher’s percentage completion of Universal Protocol components during the reward setting was 91.7% (range: 66.7% to 100%). In the work setting, the mean percentage was 95.0% (range: 66.70% to 100%). Finally, during the transition setting, the mean percentage was 93.3% (range: 80.0% to 100%). The mean interobserver agreement for the rate per minute of student challenging behaviors across settings and conditions was 97.06% (range: 75% to 100%). The mean interobserver agreement for the rate of student precursor behaviors per minute across settings and conditions was 93.06% (range: 80.4% to 100%). The mean interobserver agreement for the percentage of student engagement in work tasks in the work intervention setting was 87.7% (range: 76.8% to 95.9%).

4. Discussion

This study supports and extends previous research on the effectiveness of BST. This study examined the effects of using BST to train a special education teacher to implement a Universal Protocol treatment package for a student with challenging behavior across three school settings: reward, work, and transition. These three settings were selected because the special education teacher indicated they were often the most challenging for the student due to the high number of demands presented. A multiple-baseline across settings design demonstrated a functional relation between the teacher implementing the Universal Protocol treatment package and decreased challenging behavior by the student. Additionally, social validity results indicated that the teacher found the Universal Protocol easy to learn, was pleased with the results, and would continue using the Universal Protocol in the future with additional students. Like the student’s behavioral data shared in the previous section, this is an encouraging outcome.

Prior to implementation of the BST, baseline responding in each setting was low and stable. After BST was introduced, there was an immediate and substantial increase in the percentage of teacher-demonstrated Universal Protocol components in each setting. While there was some variability in the work and transition settings, the mean percentage of components completed remained high in all conditions. This study supports previous research on the effectiveness of BST for training staff (e.g.,

Erath et al., 2021;

Holt et al., 2024;

Li & Alber-Morgan, 2024;

Mrachko et al., 2022;

Samudre et al., 2023) and extends the findings to a special education teacher implementing the Universal Protocol.

This study also demonstrates a sensitivity between teacher implementation of the Universal Protocol and student cooperation with academic tasks. During the baseline sessions in the work setting, challenging problem behaviors and precursor behaviors occurred in almost all sessions. During baseline, the student was not given the opportunity to choose whether to cooperate and complete the assigned work tasks. By adding the opportunity to choose during intervention, the student did choose to complete the activity even when she was not required to do so. Furthermore, in the work setting, in addition to providing the opportunity to choose, the teacher made the task less demanding by separating work tasks and instructions (e.g., asking the student to match pictures, and when completed, asking her to comment about the pictures using her device).

5. Limitations and Future Directions

This study had limitations related to the participants, training components, procedural integrity, and assessment of maintenance and generalization. Regarding the participants, this study was conducted with one dyad, a special education teacher and a student with challenging behaviors. Although experimental control was achieved and the results demonstrated a clear functional relation of the independent variable with the dependent variables, the results cannot be generalized beyond the participants in this study. Future research should extend this research by conducting systematic replications that examine the effects of BST on teacher implementation of the Universal Protocol across a range of school professionals (e.g., general and special education teachers, related service providers, and support staff) and a range of students from preschool to adult with a variety of instructional needs and types of challenging behaviors.

A second limitation is that the Universal Protocol treatment was trained and implemented as a multi-component package. Therefore, it is not possible to identify which components of the protocol are most critical for student success. Future research may design a component analysis of the Universal Protocol, which can be useful for teacher training and informing practice. For example, building rapport might be the most critical feature of the Universal Protocol to focus on during staff training.

A third limitation is that the experimenter’s procedural integrity of teacher training was not assessed. Consistent implementation of training procedures is an important consideration when examining the results. Future research should conduct a formal procedural integrity measure of the experimenter’s delivery of training. Despite this limitation, the experimenter’s training was effective for the teacher achieving a high level of treatment integrity (see

Figure 1).

A fourth limitation was that experimental control of the teacher’s implementation of the Universal Protocol on the student’s problem behavior was not demonstrated. Despite this, the large reduction in the student’s challenging and precursor behaviors was promising, and future research could attempt to establish a functional relationship between Universal Protocol implementation and student behavior(s).

Finally, due to time and logistical constraints, the experimenters in this study did not collect data on the maintenance and generalization of teacher behavior and student outcomes. Future research should examine the extent to which teachers and staff can transfer Universal Protocol skills to other learners, settings, and situations, as well as over time. Additionally, future research should examine the extent to which student participants’ challenging behavior decreases in other non-training settings with other adults.

6. Conclusions

This study evaluated the implementation of the Universal Protocol as a treatment package delivered in a school environment by a special education teacher. This is the first experimental research study to examine the effects of the Universal Protocol as a treatment package, which means that a considerable amount of further research will be needed to prove its overall effectiveness. The Universal Protocol shows promise as practice for teachers and staff to use in schools. The Universal Protocol has the potential to create school environments and relationships that minimize the need for more intensive, restrictive, and costly interventions for the school and student. Based on the findings of this study, teachers may find success with addressing challenging behaviors by offering students choices, reducing the number of demands, and providing a reinforcement-rich environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W.D.J.; methodology, R.W.D.J.; investigation, R.W.D.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W.D.J.; writing—review and editing, R.W.D.J., A.C.-S.; visualization, R.W.D.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research was approved by The Ohio State University’s Behavioral and Social Sciences Institutional Review Board (Protocol #2021B0392) on 12 January 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sheila R. Alber-Morgan for her support and guidance. Special thanks to Megan Donegan for her participation. Thanks to Ghazaleh Raei Dehaghi for completing a portion of the IOA data collection..

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amos, P. A. (2004). New considerations in the prevention of aversives, restraint, and seclusion: Incorporating the role of relationships into an ecological perspective. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 29(4), 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erath, T. G., Digennaro Reed, F. D., & Blackman, A. L. (2021). Training human service staff to implement behavioral skills training using a video-based intervention. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 54(3), 1251–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmie, T. A., & Iwata, B. A. (2011). Topographical and functional properties of precursors to severe problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(4), 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, T. W., Reinke, W. M., & Brooks, D. S. (2014). Managing classrooms and challenging behavior. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 22(2), 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gover, H. C., Fahmie, T. A., & McKeown, C. A. (2019). A review of environmental enrichment as treatment for problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(1), 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gover, H. C., Staubitz, J. E., & Juárez, A. P. (2022). Revisiting reinforcement: A focus on happy, relaxed, and engaged students. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 55(1), 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, G. H., & Ruppel, K. (2021). Increasing safety, dignity, and joy across the day: Universal protocols 498 [webinar]. FTF Behavioral Consulting. Available online: https://ftfbc.com/courses/increasing-safety-dignity-and-joy-across-the-day-universal-protocols/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Hanley, G. P. (2022). Practical functional assessment & skill based treatment workbook [powerpoint presentation]. FTFBC Website. Available online: https://ftfbc.com/courses/dr-gregory-hanley-presents-practical-functional-assessment-and-skill-based-treatment-10-ceus/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Hanley, G. P., Jin, C. S., Vanselow, N. R., & Hanratty, L. A. (2014). Producing meaningful improvements in problem behavior of children with autism via synthesized analyses and treatments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, H., & Smith, R. G. (2019). Precursor behavior and functional analysis: A brief review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(3), 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, A., Knez, N., & Kahng, S. (2014). Evaluating the use of behavioral skills training to improve school staffs’ implementation of behavior intervention plans. Journal of Behavioral Education, 24(2), 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, L., & Bigby, C. (2024). Supporting people with complex and challenging behaviour. In C. Bigby, & A. Hough (Eds.), Disability practice: Safeguarding quality service delivery (1st ed., pp. 161–182). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A. K., Drasgow, E., & Wolfe, K. (2024). Training teachers of children with moderate to significant support needs to contingently respond to child-initiated social participation behaviors during centers. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 49(2), 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, D. C., Hawkins, L., Hillman, C., Shireman, M., & Nissen, M. A. (2015). Adults with autism spectrum disorder as behavior technicians for young children with autism: Outcomes of a behavioral skills training program. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(2), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T., & Alber-Morgan, S. R. (2024). Training staff to implement free-operant preference assessment: Effects of remote behavioral skills training. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lory, C., Mason, R. A., Davis, J. L., Wang, D., Kim, S. Y., Gregori, E., & David, M. (2020). A meta-analysis of challenging behavior interventions for students with developmental disabilities in inclusive school settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(4), 1221–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, D. M., & Carr, E. G. (2005). Quality of rapport as a setting event for problem behavior: Assessment and intervention. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7(2), 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrachko, A. A., Kaczmarek, L. A., Kostewicz, D. E., & Vostal, B. (2022). Teaching therapeutic support staff to implement NDBI strategies for children with ASD using behavior skills training. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 42(4), 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nankervis, K., Ashman, A., Weekes, A., & Carroll, M. (2019). Interactions of residents who have intellectual disability and challenging behaviours. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 67(1), 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M. B., Rollyson, J. H., & Reid, D. H. (2013). Teaching practitioners to conduct behavioral skills training: A pyramidal approach for training multiple human service staff. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 6(2), 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, A., Austin, J. L., & Gover, H. C. (2023). A practitioner’s guide to emphasizing choice-making opportunities in behavioral services provided to individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 69(1), 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppar, A. L., Roberts, C. A., & Olson, A. J. (2017). Perceptions about expert teaching for students with severe disabilities among teachers identified as experts. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 42(2), 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppel, K. W., & Ingvarsson, E. T. (2025). Prevention and behavioral hygiene procedures. In J. Jessel, & P. Sturmey (Eds.), A practical guide to functional assessment and treatment for severe problem behavior (pp. 39–64). Elsevier, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Samudre, M. D., Allday, R. A., Jones, M., & Fisher, A. (2023). Behavioral skills training to teach pre-service elementary general educators to conduct descriptive assessments. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 68(3), 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, J. M., & Andzik, N. R. (2021). Evaluating behavioral skills training as an evidence-based practice when training parents to intervene with their children. Behavior Modification, 45(6), 887–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simó-Pinatella, D., Mumbardó-Adam, C., Alomar-Kurz, E., Sugai, G., & Simonsen, B. (2019). Prevalence of challenging behaviors exhibited by children with disabilities: Mapping the literature. Journal of Behavioral Education, 28(3), 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slane, M., & Lieberman-Betz, R. G. (2021). Using behavioral skills training to teach implementation of behavioral interventions to teachers and other professionals: A systematic review. Behavioral Interventions, 36(4), 984–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobeck, E. E., & Reister, M. (2020). Preventing challenging behavior: 10 behavior management strategies every teacher should know. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 65(1), 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoesz, B. M., Shooshtari, S., Montgomery, J., Martin, T., Heinrichs, D. J., & Douglas, J. (2014). Reduce, manage or cope: A review of strategies for training school staff to address challenging behaviours displayed by students with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16(3), 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T. J., Walker, M. W., Leboeuf, J. B., Simeonsson, R. J., & Karakul, E. (2022). Chronicity of challenging behaviors in persons with severe/profound intellectual disabilities who received active treatment during a 20-Year period. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(2), 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2002). Invitations to learn. Educational Leadership, 60(1), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, C. A., Hanley, G. P., Landa, R. K., Ruppel, K. W., Rajaraman, A., Ghaemmaghami, M., Slaton, J. D., & Gover, H. C. (2020). Toward accurate inferences of response class membership. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(1), 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westing, D. L. (2015). Evidence-based practices for improving challenging behaviors of students with severe disabilities (Document No. IC-14). University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability, and Reform Center. Available online: https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EBPs-for-improving-challenging-behavior-of-SWD.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).