Teachers Training Paraeducators to Implement Systematic Prompting Practices for Students with Significant Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the efficacy of teacher-implemented tiered training on paraeducator adherence to systematic prompting strategies (i.e., simultaneous prompting and least-to-most prompting) with students with significant disabilities? What are the contributions of the individual tiers of training, including group training (Tier 1) and one-to-one coaching (Tier 2)?

- When directed to use systematic prompting strategies in a new teaching situation for which they have received no coaching or feedback, to what degree do paraeducators generalize their adherence?

- How does paraeducator implementation quality change after receiving tiered training?

- What progress do students make on individualized goals after receiving instruction from paraeducators who have participated in tiered training?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Settings

2.2. Experimental Design and Procedures

2.2.1. Student Goal Selection, Teacher Training, and Task Analyses of Chained Skills (Pre-Baseline)

2.2.2. Written Directions (Baseline)

2.2.3. Group Training for Paraeducators

2.2.4. Maintenance

2.2.5. Individual Coaching

2.3. Dependent Measures and Recording

2.3.1. Classroom Observations

2.3.2. Observer Training and Reliability

2.4. Procedural Fidelity

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

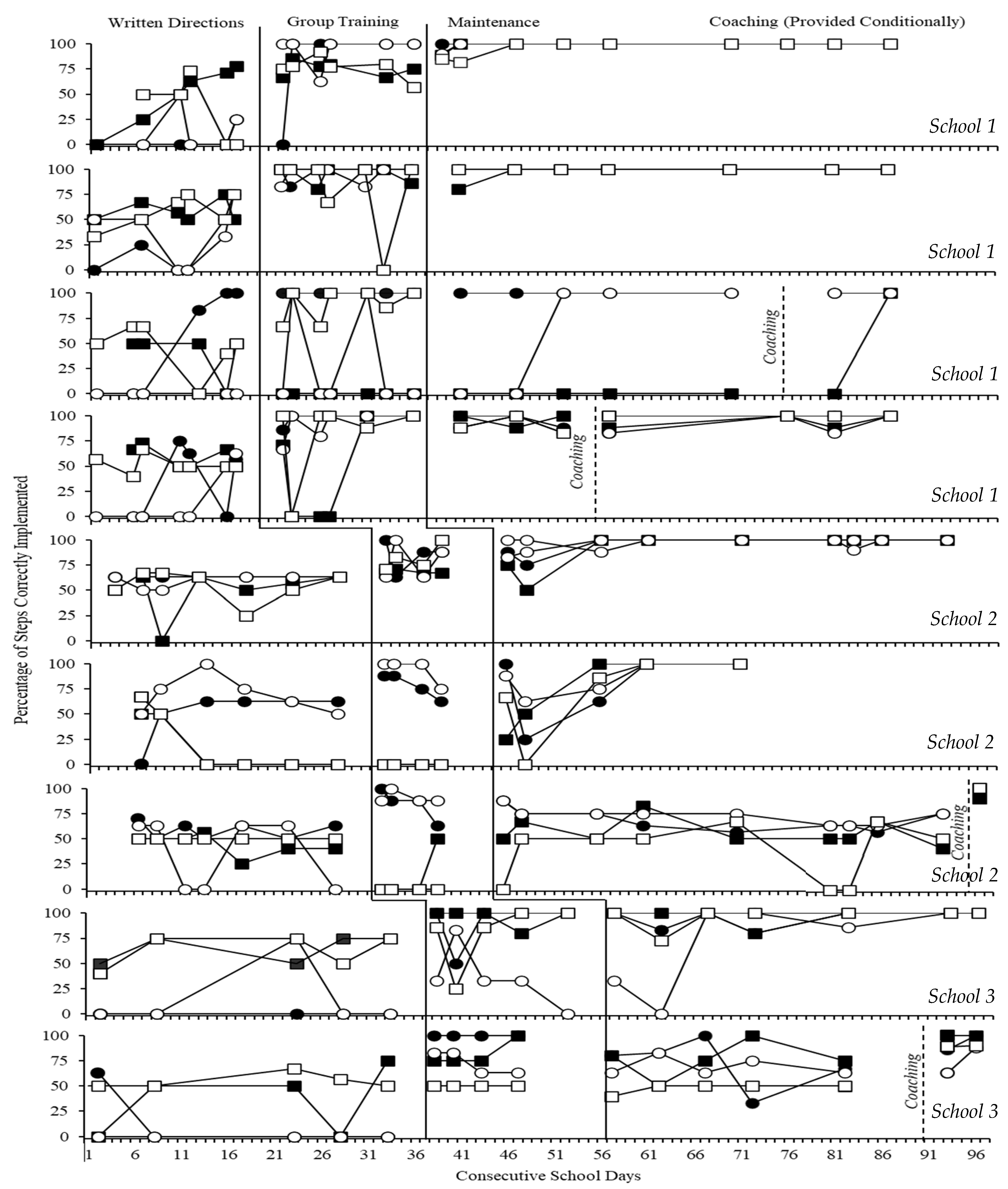

3.1. Paraeducator Implementation of Systematic Instructional Strategies

3.1.1. Adherence to Steps for Simultaneous Prompting

3.1.2. Adherence to Steps for Least-to-Most Prompting

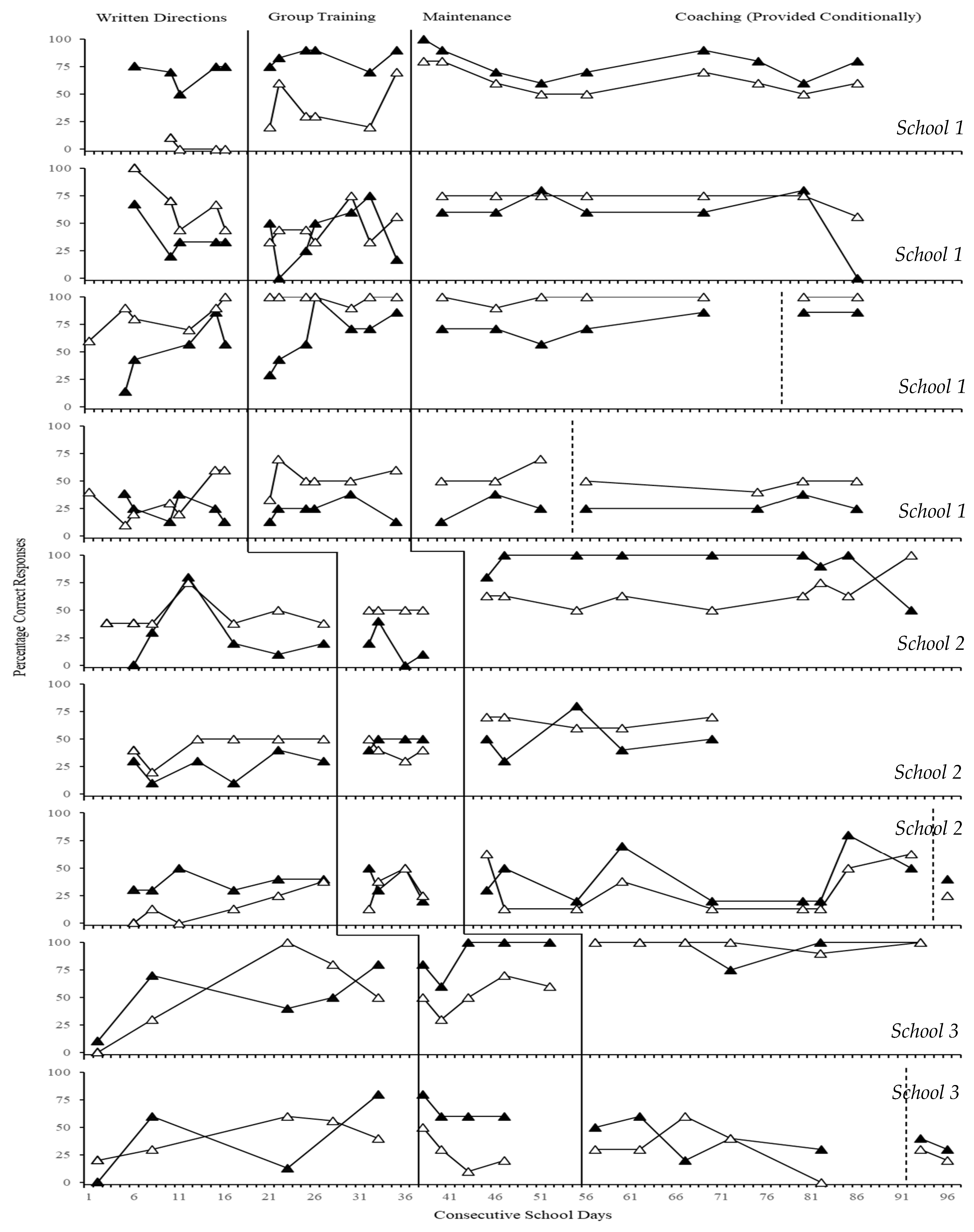

3.1.3. Implementation Quality

3.2. Student Progress on Individualized Goals

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions for Research

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andzik, N. R., & Cannella-Malone, H. I. (2019). Practitioner implementation of communication intervention with students with complex communication needs. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 124, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisht, B., LeClair, Z., Loeb, S., & Sun, M. (2021). Paraeducators: Growth, diversity and a dearth of professional supports (EdWorkingPaper No. 21-490). Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borosh, A. M., Newson, A., Mason, R. A., Richards, C. D., & Collins Crosley, H. (2023). Special education teacher-delivered training for paraeducators: A systematic and quality review. Teacher Education and Special Education, 46(3), 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, N. S., Collins, B. C., Ault, M. J., & Bausch, M. E. (2017). Using a constant time delay procedure to teach support personnel to use a simultaneous prompting procedure. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 32, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E. (2022). A tiered approach for training paraeducators to use evidence-based practices for students with significant disabilities. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 54(3), 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., & Anderson, E. J. (2021). Training paraprofessionals who work with students with intellectual and developmental disabilities: What does the research say? Psychology in the Schools, 58(4), 702–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., Barczak, M. A., Anderson, E. J., & Bordner-Williams, N. M. (2021a). Efficacy of tiered training on paraeducator implementation of systematic instructional practices for students with severe disabilities. Exceptional Children, 87(2), 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., Barczak, M. A., & Dueker, S. A. (2021b). A randomized evaluation of group training for paraprofessionals to implement systematic instruction strategies with students with severe disabilities. Teacher Education and Special Education, 44(3), 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., Cannella-Malone, H. I., Seaman, R. L., Andzik, N. R., Schaefer, J. M., Page, E. J., Barczak, M., & Dueker, S. (2017). Findings across practitioner training studies in special education: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Exceptional Children, 84, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., & Carter, E. W. (2013). A systematic review of paraprofessional-delivered educational practices to improve outcomes for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 38, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., & Carter, E. W. (2015). Effects of a professional development package to prepare special education paraprofessionals to implement evidence-based practice. The Journal of Special Education, 49, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., & Carter, E. W. (2016). Efficacy of teachers training paraprofessionals to implement peer support arrangements. Exceptional Children, 82, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., & Carter, E. W. (2017). A meta-analysis of educator training to improve implementation of interventions for students with disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 38, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E., O’Rourke, L., Sisco, L. G., & Pelsue, D. (2009). Knowledge, responsibilities, and training needs of paraprofessionals in elementary and secondary schools. Remedial and Special Education, 30, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y. C., Douglas, K. H., Walker, V. L., & Wells, R. L. (2019). Interactions of high school students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in inclusive classrooms. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 57(4), 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, S., Collins, B. C., Knight, V., & Spriggs, A. D. (2016). Embedded simultaneous prompting procedure to teach stem content to high school students with moderate disabilities in an inclusive setting. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill, T. R., & Levin, J. R. (Eds.). (2014). Single-case intervention research: Methodological and statistical advances. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, J. R., & Gast, D. L. (2024). Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. A., Schnitz, A. G., Wills, H. P., Rosenbloom, R., Kamps, D. M., & Bast, D. (2017). Impact of a teacher-as-coach model: Improving paraprofessionals fidelity of implementation of discrete trial training for students with moderate-to-severe developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 1696–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitzel, J., & Wolery, M. (2009a). Steps for implementation: Least-to-most prompts. National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute; The University of North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Neitzel, J., & Wolery, M. (2009b). Steps for implementation: Time delay. The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute; The University of North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, C. L. (2008). Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring fidelity of implementation and its relationship to outcomes in K–12 curriculum intervention research. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 33–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustejovsky, J. E., Chen, M., Hamilton, B., & Grekov, P. (2023). scdhlm: A web-based calculator for between-case standardized mean differences (Version 0.7.2) [Web application]. Available online: https://jepusto.shinyapps.io/scdhlm (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Pustejovsky, J. E., Hedges, L. V., & Shadish, W. R. (2014). Design-comparable effect sizes in multiple baseline designs: A general modeling framework. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 39(5), 368–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheeler, M. C., Morano, S., & Lee, D. L. (2018). Effects of immediate feedback using bug-in-ear with paraeducators working with students with autism. Teacher Education and Special Education, 41, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawbitz, K. N., & Brock, M. E. (2023). A systematic review of training educators to implement response prompting. Teacher Education and Special Education, 46(2), 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobeck, E. E., Douglas, S. N., Chopra, R., & Morano, S. (2021). Paraeducator supervision in pre-service teacher preparation programs: Results of a national survey. Psychology in the Schools, 58(4), 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization 1. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10(2), 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suter, J. C., & Giangreco, M. F. (2009). Numbers that count: Exploring special education and paraprofessional service delivery in inclusion-oriented schools. The Journal of Special Education, 43, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Individuals Education Improvement Act (IDEIA). (2004). Individuals with disabilities education act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/108th-congress/house-bill/1350/text (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Walker, V. L., Douglas, K. H., & Chung, Y. C. (2017). An evaluation of paraprofessionals’ skills and training needs in supporting students with severe disabilities. International Journal of Special Education, 32(3), 460–471. [Google Scholar]

- Wermer, L., Brock, M. E., & Seaman, R. L. (2017). Efficacy of a teacher coaching a paraprofessional to promote communication for a student with autism and complex communication needs. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disorders, 33, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| School # | Teachers | Paraeducators | Students | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Years Exper. | Highest Educat. | # | Gender | Years Exper. | Age | Grade | Disability | IQ Score | Adaptive Behavior Score | |

| 1 | Female | 4 | Master’s | 1 | Male | 3 | 13 | 7 | MD | NV a | 64 b |

| 2 | Female | 4 | 12 | 6 | ASD | NR | <70 c,e | ||||

| 3 | Female | 12 | 14 | 8 | MD | NV | NR | ||||

| 4 | Female | 3 | 15 | 8 | ASD | NR | 49 | ||||

| 2 | Female | 1 | Under-graduate | 1 | Female | NR | 9 | 3 | ID | 52 d | NR |

| 2 | Female | NR | 9 | 3 | MD | NV a | NR | ||||

| 3 | Male | <1 | 9 * | 3 * | MD * | NV a,* | NR * | ||||

| 3 | Female | 13 | Master’s | 1 | Female | 2 | 13 | 7 | ASD | NR | 54 c |

| 2 | Female | 4 | 14 | 8 | ASD | NR | 48 c | ||||

| School Number | Para Number | Primary Goal | Generalization Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Telling time to the half hour | Identifying simple fractions |

| 2 | Identifying first name in print | Stamping name onto written work | |

| 3 | Typing first name | Identifying community signs | |

| 4 | Identifying coins by name and value | Identifying community signs | |

| 2 | 1 | One-digit addition | Identifying coins by name and value |

| 2 | Identifying letters by their sound | Identifying numbers 1–10 | |

| 3 | Identifying letters by their name | Identifying coins by name and value | |

| 3 | 1 | Counting combinations of 1, 5, and 10-dollar bills | Two-digit addition |

| 2 | Counting manipulatives up to 10 | Reading high-frequency sight words |

| School Number | Paraeducator Number | Average Implementation Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Intervention | ||

| 1 | 1 | 2.24 (1.83–2.50) | 2.71 (2.60–3.00) |

| 2 | 2.20 (1.67–2.67) | 2.86 (2.50–3.00) | |

| 3 | 1.88 (1.00–2.50) | 2.41 (2.00–2.83) | |

| 4 | 2.31 (1.67–2.83) | 2.69 (2.50–3.00) | |

| 2 | 1 | 2.28 (2.00–2.50) | 2.00 (1.67–2.67) |

| 2 | 1.94 (1.67–2.33) | 2.50 (2.50–2.50) | |

| 3 | 1.89 (1.67–2.33) | 2.50 (2.50–2.50) | |

| 3 | 1 | 2.31 (2.00–2.50) | 2.80 (2.50–3.00) |

| 2 | 1.68 (1.00–2.60) | 2.20 (2.00–3.00) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brock, M.E.; Barczak, M.A.; Shawbitz, K.N.; Hurlburt, G. Teachers Training Paraeducators to Implement Systematic Prompting Practices for Students with Significant Disabilities. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040460

Brock ME, Barczak MA, Shawbitz KN, Hurlburt G. Teachers Training Paraeducators to Implement Systematic Prompting Practices for Students with Significant Disabilities. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040460

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrock, Matthew E., Mary A. Barczak, Kara N. Shawbitz, and Genevieve Hurlburt. 2025. "Teachers Training Paraeducators to Implement Systematic Prompting Practices for Students with Significant Disabilities" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040460

APA StyleBrock, M. E., Barczak, M. A., Shawbitz, K. N., & Hurlburt, G. (2025). Teachers Training Paraeducators to Implement Systematic Prompting Practices for Students with Significant Disabilities. Education Sciences, 15(4), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040460