Unveiling Potential: Fostering Students’ Self-Concepts in Science Education by Designing Inclusive Educational Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Scientific Literacy and Social Participation

1.2. Motivation for Science through Storytelling

1.3. Aim and Hypothesis

1.4. Overview of the Results

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Design

2.2. Material and Measures

2.2.1. Development of a Digital Learning Environment in Science Education

2.2.2. Instruments: Questionnaires on Self-Concept and on Accessibility

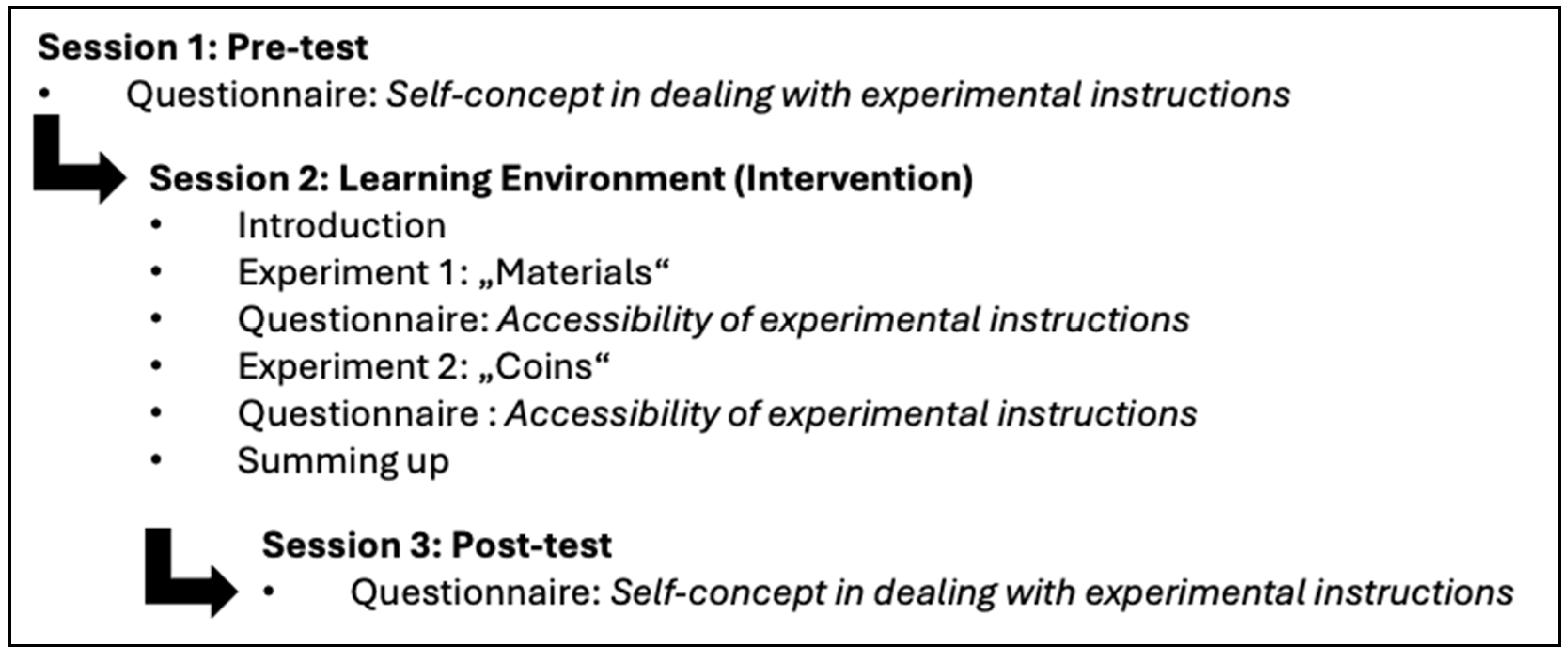

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

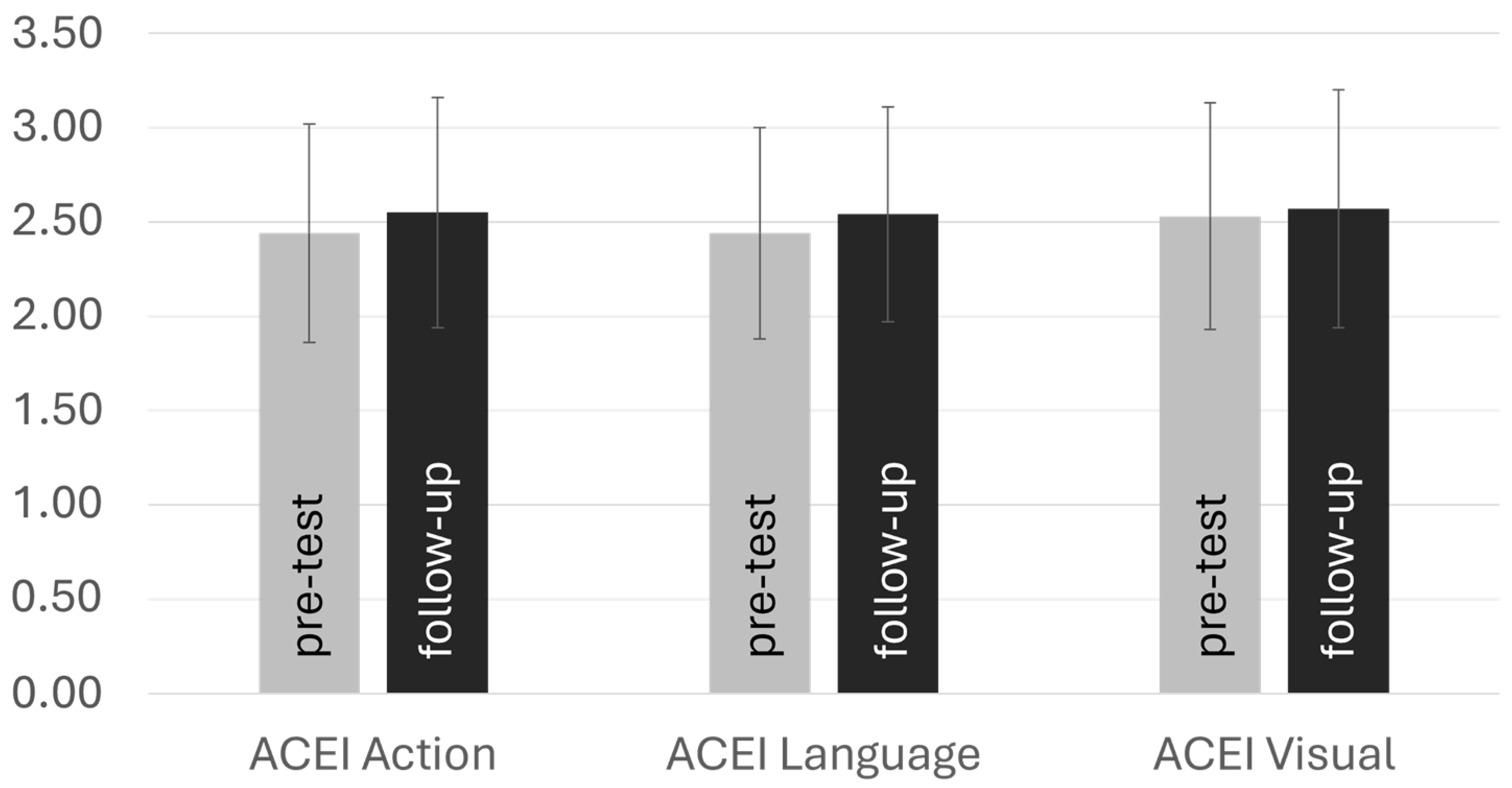

3.1. Perception of Accessibility of Experimental Instructions

3.1.1. Dimension: Action

3.1.2. Dimension: Language

3.1.3. Dimension: Visibility

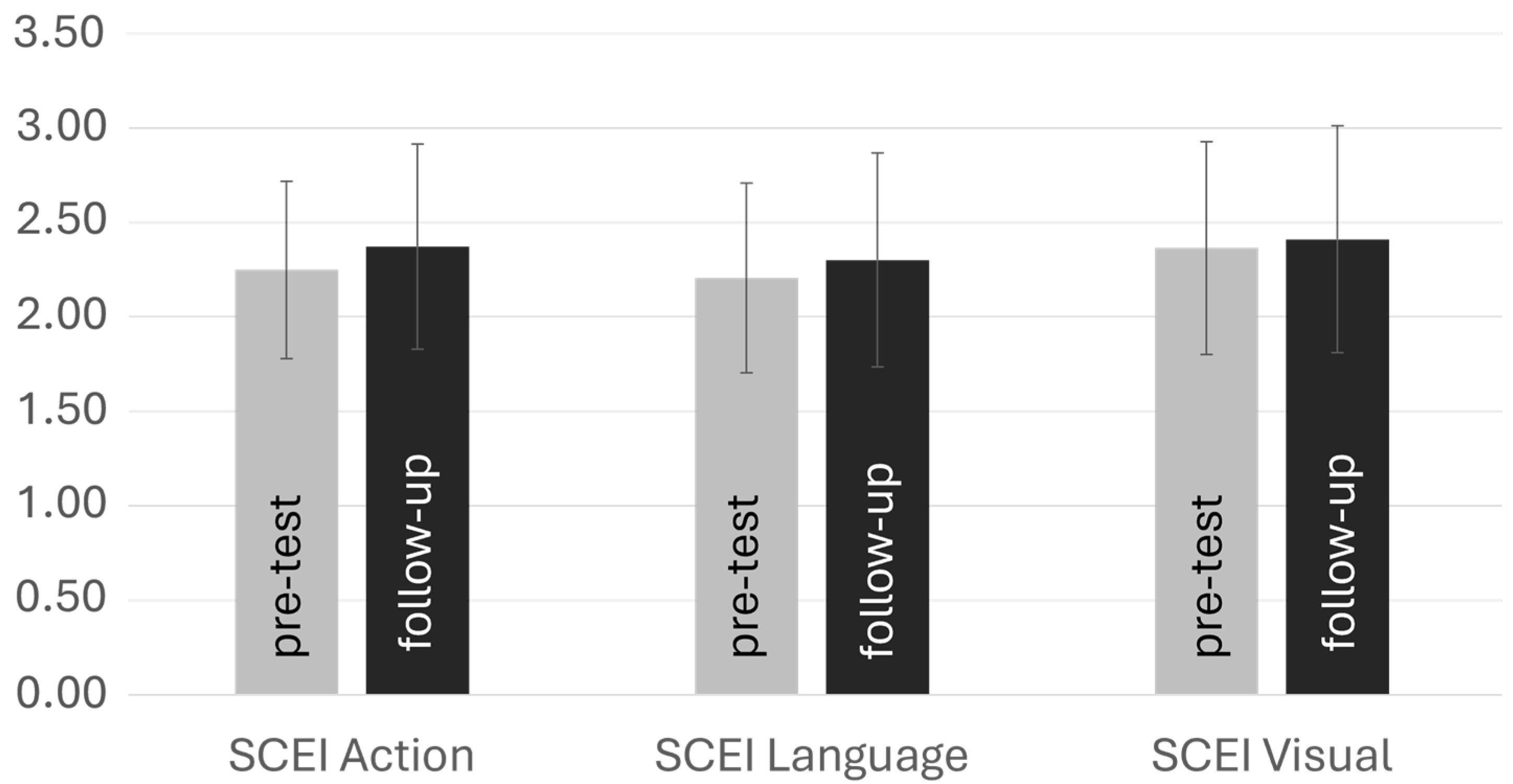

3.2. Development of the Ability Self-Concept in Engaging with Experimental Instructions

3.2.1. Dimension: Action

3.2.2. Dimension: Language

3.2.3. Dimension: Visibility

3.3. Influence of the Accessibility on the Development of the Self-Concept

3.4. Influences on the Self-Concept with Experimental Instructions

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Education in a Post-COVID World: Nine Ideas for Public Action. 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373717/PDF/373717eng.pdf.multi (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Miller, J.D. Scientific Literacy: A Conceptual and Empirical Review. Daedalus 1983, 112, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J. Science for citizenship. In Good Practice in Science Teaching: What Research Has to Say, 2nd ed.; Osborne, J., Dillon, J., Eds.; McGraw-Hill/Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2010; pp. 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, D.H.; Meyer, A. Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age. In Universal Design for Learning; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2. 2018. Available online: http://udlguidelines.cast.org (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Moore, S.L.; David, H. Rose, Anne Meyer, Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2007, 55, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinken-Rösner, L.; Rott, L.; Hundertmark, S.; Baumann, T.; Menthe, J.; Hoffmann, T.; Nehring, A.; Abels, S. Thinking Inclusive Science Education from Two Perspectives: Inclusive Pedagogy and Science Education. Res. Subj.-Matter Teach. Learn. 2020, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettle, M.; Mikelskis-Seifert, S.; Scharenberg, K.; Rollett, W. Erfassung der Barrierefreiheit von schulischen Experimentierumgebungen [Assessing the accessibility of school experiment environments. In Naturwissenschaftlicher Unterricht und Lehrerbildung im Umbruch? Science Teaching and Teacher Training in Transition? Habig, S., Ed.; University Duisburg-Essen: Duisburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Graichen, M.; Mikelskis-Seifert, S.; Oettle, M.; Scharenberg, K.; Rollett, W. (in preparation). Evaluating the Accessibility of Experimental Instructions in Inclusive Science Classrooms.

- Brotman, J.S.; Moore, F.M. Girls and Science: A Review of Four Themes in the Science Education Literature. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2008, 45, 971–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L. Promoting Girls’ Interest and Achievement in Physics Classes for Beginners. Learn. Instr. 2002, 12, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PISA 2015 Results; OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Ed.; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kerger, S.; Martin, R.; Brunner, M. How can we enhance girl’s interest in scientific topics? Br. Psychol. Soc. 2011, 81, 606–628. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, N.; Stout, J.G. Girls and Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics: STEMing the Tide and Broadening Participation in STEM Careers. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2014, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, E.; Mammes, I.; Münk, D. Career choice of women and men in STEM. Why gendered career choices are still an issue and how to address them. In Future Prospects of Technology Education, 4th ed.; de Vries, M.J., Fletcher, S., Kruse, S., Labudde, P., Lang, M., Mammes, I., Max, C., Münk, D., Nicholl, B., Strobel, J., et al., Eds.; Waxman: Münster, Germany, 2024; pp. 169–186. ISBN 978-3-8309-9781-8. [Google Scholar]

- BDA (Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Arbeitgeberverbände = Federation of German Employers’ Associations. The Economy Lacks Almost 286,000 Workers in the STEM Sector. Available online: https://arbeitgeber.de/en/the-economy-lacks-almost-286000-workers-in-the-stem-sector/#:~:text=Domestic%20STEM%20talent%20cannot%20meet,choice%20of%20training%20and%20career (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- World Economic Forum. What Can Employer Do to Combat STEM Talent Shortages? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/05/what-can-employers-do-to-combat-stem-talent-shortages/ (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Mahboudi, P. The Knowledge Gap: Canada Faces a Shortage in Digital and Stem Skills, 1st ed.; C.D. How Institute: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Craven, R.G. Reciprocal Effects of Self-Concept and Performance from a Multidimensional Perspective: Beyond Seductive Pleasure and Unidimensional Perspectives. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavelson, R.J.; Hubner, J.J.; Stanton, G.C. Self-Concept: Validation of Construct Interpretations. Rev. Educ. Res. 1976, 46, 407–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Martin, A.J. Academic Self-Concept and Academic Achievement: Relations and Causal Ordering: Academic Self-Concept. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 81, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.A.; Häusler, J.; Jurik, V.; Seidel, T. Self-Underestimating Students in Physics Instruction: Development over a School Year and Its Connection to Internal Learning Processes. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 43, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.M.; Klassen, R.M. Relations of Mathematics Self-Concept and Its Calibration with Mathematics Achievement: Cultural Differences among Fifteen-Year-Olds in 34 Countries. Learn. Instr. 2010, 20, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misrulloh, A.; Dewi, N.R. Influence of Science Digital Storytelling against Motivation of Learning and Critical Thinking Ability Learners. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1567, 042048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, R.; Yayon, M.; Katchevich, D.; Mamlok-Naaman, R.; Fortus, D.; Eilks, I.; Hofstein, A. Teachers’ Views on Implementing Storytelling as a Way to Motivate Inquiry Learning in High-School Chemistry Teaching. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2017, 18, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saritepeci, M. Students’ and Parents’ Opinions on the Use of Digital Storytelling in Science Education. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2021, 26, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromka, S.M.; Goodboy, A.K. Classroom Storytelling: Using Instructor Narratives to Increase Student Recall, Affect, and Attention. Commun. Educ. 2019, 68, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laçin-Şimşek, C. What Can Stories on History of Science Give to Students? Thoughts of Science Teachers Candidates. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, S.; Froese Klassen, C. Science Teaching with Historically Based Stories: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives. In International Handbook of Research in History, Philosophy and Science Teaching; Matthews, M.R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1503–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh-Spencer, H. Teaching with Stories: Ecology, Haraway, and Pedagogical Practice. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2019, 38, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, N. The Patterns of Comics: Visual Languages of Comics from Asia, Europe, and North America; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, T.F. Poon. Telling a Compelling Story: An Exploration of Cognitive Simplicity in Comic Book Design and Characterisation as Visual Communication for Political, Cultural and Social Influence. Wacana Seni. J. Arts Discourse 2022, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcanca, N. An Alternative Teaching Tool in Science Education: Educational Comics. Int. Online J. Educ. Teach. IOJET 2020, 7, 1550–1570. [Google Scholar]

- Jee, B.D.; Anggoro, F.K. Comic Cognition: Exploring the Potential Cognitive Impacts of Science Comics. J. Cogn. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 11, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, E.; Eryılmaz, A. Comics in Science Teaching: A Case of Speech Balloon Completing Activity for Heat Related Concepts. J. Inq. Based Act. JIBA 2019, 9, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- De Hosson, C.; Bordenave, L.; Daures, P.-L.; Décamp, N.; Hache, C.; Horoks, J.; Guediri, N.; Matalliotaki-Fouchaux, E. Communicating Science through the Comics & Science Workshops: The Sarabandes Research Project. J. Sci. Commun. 2018, 17, A03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Mayer, R.E., Fiorella, L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. The Past, Present, and Future of the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 36, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnotz, W.; Bannert, M. Construction and Interference in Learning from Multiple Representation. Learn. Instr. 2003, 13, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Nine Ways to Reduce Cognitive Load in Multimedia Learning. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 38, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclellan, E. How Might Teachers Enable Learner Self-Confidence? A Review Study. Educ. Rev. 2014, 66, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfer, L. Evaluation of learning in science. In Handbook of Formative and Summative Evaluation of Student Learning; Bloom, B., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1971; pp. 599–641. [Google Scholar]

- Mikelskis-Seifert, S.; Duit, R. Naturwissenschaftliches Arbeiten [Working in the Sciences]. PIKO-Brief 6 [Physics in Context Letter 6]. 2010. Available online: https://www.leibniz-ipn.de/de/das-ipn/abteilungen/didaktik-der-physik/piko (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Kihm, P.; Diener, J.; Peschel, M. Kinder forschen–Wege zur (gemeinsamen) Erkenntnis [Children do research-paths to (shared) knowledge]. In Fachlichkeit in Lernwerkstätten. Kind und Sache in Lernwerkstätten [Professionalism in Learning Workshops. Child and Object in Learning Workshops]; Peschel, M., Kelkel, M., Eds.; Verlag Julius Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2018; pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Transfer Effects in a Problem Solving Context. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1980, 32, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singley, M.K.; Anderson, J.R. The Transfer of Cognitive Skill; Cognitive science series; Harvard Univ. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, K.; Weis, M.; Klieme, E.; Köller, O. PISA 2018. Grundbildung im Internationalen Vergleich [Basic Education in International Comparison]; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, J.; Wirth, J.; Rumann, S.; Leutner, D. Strukturen fächerübergreifender und fachlicher Problemlösekompetenz. Analyse von Aufgabenprofilen. Projekt Problemlösen [Structures of interdisciplinary and subject-specific problem-solving skills. Analysis of task profiles. Problem solving project]. In Kompetenzmodellierung. Zwischenbilanz des DFG-Schwerpunktprogramms und Perspektiven des Forschungsansatzes [Competence modeling. Interim Results of the DFG Priority Program and Perspectives of the Research Approach]; Klieme, E., Leutner, D., Kenk, M., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe, F.; McElvany, N.; Trendtel, M. Reading Skills of Students in Different School Tracks: Systematic (Dis)Advantages Based on Item Formats in Large Scale Assessments. Z. Für Erzieh. 2015, 18, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabborang, C.R.; Balero, S.M. Exploring Factors Affecting Reading Comprehension Skills: A Quasi-Experimental Study on Academic Track Strands, Learning Modalities, and Gender. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 11, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, A.; Van Keer, H.; Merchie, E. The Profile of the Skilled Reader: An Investigation into the Role of Reading Enjoyment and Student Characteristics. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 99, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohm, T.; Carstensen, C.H.; Fischer, L.; Gnambs, T. The Achievement Gap in Reading Competence: The Effect of Measurement Non-Invariance across School Types. Large-Scale Assess. Educ. 2021, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Guo, D.; Chen, G.; Yang, J. Effects of Repetition Learning on Associative Recognition Over Time: Role of the Hippocampus and Prefrontal Cortex. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, M. Repetition and Transformation in Learning. In Transformative Learning Meets Bildung: An International Exchange; La Rosée, A., Fuhr, T., Taylor, E.W., Eds.; International issues in adult education; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA; Taipei, Taiwan, 2017; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, B.L.; Sefi-Cyr, H.; Lily, L.S.; Dahlberg, C.L. Repetition Is Important to Students and Their Understanding during Laboratory Courses That Include Research. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2021, 22, e00158-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintzman, D.L. Repetition and Memory. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976; Volume 10, pp. 47–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | Dimension | Number of Items | Reliability (Cronbach α) | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | ||||

| Accessibility | Action | 8 | 0.86 | 0.93 | The instructions explained exactly what I had to do. I did not need any further help with the instructions. |

| Language | 4 | 0.74 | 0.82 | I was able to understand the sentences in the instructions very well. The language of the instructions was just right for me. | |

| Visibility | 4 | 0.82 | 0.88 | The pictures in the instructions were sharp. The images in the instructions were clearly recognizable. | |

| Self-Concept | Action | 10 | 0.93 | 0.95 | I can easily carry out an experiment with instructions. When experimenting with instructions, I always know what I have to do next. |

| Language | 5 | 0.88 | 0.93 | I know all the words in an experimental instruction. I can easily read texts in an experimental instruction. | |

| Visibility | 4 | 0.87 | 0.91 | I can clearly see the pictures in an experimental instruction. I think the pictures in the instructions are large enough. | |

| n | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Language | Visibility | Action | Language | Visibility | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Gender | Girls | 147 | 2.44 | 0.57 | 2.41 | 0.64 | 2.53 | 0.62 | 2.54 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.64 | 2.56 | 0.64 |

| Boys | 146 | 2.47 | 0.53 | 2.49 | 0.51 | 2.60 | 0.51 | 2.59 | 0.51 | 2.64 | 0.53 | 2.63 | 0.57 | |

| School | Academic | 141 | 2.71 | 0.44 | 2.67 | 0.40 | 2.66 | 0.38 | 2.78 | 0.43 | 2.75 | 0.39 | 2.78 | 0.34 |

| Non-academic | 157 | 2.41 | 0.64 | 2.45 | 0.58 | 2.26 | 0.61 | 2.41 | 0.69 | 2.40 | 0.69 | 2.37 | 0.64 | |

| Grade | 5 | 134 | 2.50 | 0.56 | 2.49 | 0.56 | 2.64 | 0.57 | 2.63 | 0.57 | 2.64 | 0.57 | 2.67 | 0.63 |

| 6 | 159 | 2.42 | 0.54 | 2.42 | 0.59 | 2.50 | 0.56 | 2.51 | 0.54 | 2.52 | 0.61 | 2.54 | 0.58 | |

| n | Self-Concept 1 (Pre-Test) | Self-Concept 2 (Follow-Up) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Language | Visibility | Action | Language | Visibility | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Gender | Girls | 146 | 2.38 | 0.53 | 2.21 | 0.51 | 2.26 | 0.46 | 2.40 | 0.58 | 2.27 | 0.55 | 2.37 | 0.52 |

| Boys | 151 | 2.35 | 0.59 | 2.2 | 0.50 | 2.24 | 0.47 | 2.42 | 0.62 | 2.33 | 0.59 | 2.38 | 0.56 | |

| School | Academic | 140 | 2.40 | 0.43 | 2.36 | 0.39 | 2.41 | 0.56 | 2.53 | 0.40 | 2.48 | 0.40 | 2.48 | 0.57 |

| Non-acad. | 163 | 2.13 | 0.53 | 2.06 | 0.54 | 2.32 | 0.56 | 2.23 | 0.60 | 2.13 | 0.63 | 2.33 | 0.62 | |

| Grade | 5 | 135 | 2.27 | 0.45 | 2.24 | 0.44 | 2.43 | 0.56 | 2.43 | 0.52 | 2.34 | 0.54 | 2.49 | 0.59 |

| 6 | 162 | 2.23 | 0.48 | 2.18 | 0.54 | 2.31 | 0.56 | 2.32 | 0.55 | 2.27 | 0.59 | 2.34 | 0.60 | |

| Effects | Accessibility | Self-Concept | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Language | Visibility | Action | Language | Visibility | ||

| Main | Measurement | m/m/m | m/m/m | --/--/-- | --/w/w | w/w/w | w/--/-- |

| Gender | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| School track | large | med | med | med | med | weak | |

| Grade | -- | -- | weak | -- | -- | weak | |

| Interaction with measurement | Gender | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| School track | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Grade | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Accessibility | Delta Self-Concept | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Action | 260 | 2.52 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.51 |

| Language | 260 | 2.52 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 0.56 |

| Visibility | 260 | 2.58 | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.63 |

| 95% CI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | b | SE | beta | t | p | LL | UL | |

| Action | Intercept | 0.26 | 0.04 | 6.22 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.34 | |

| 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.27 | 4.58 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.15 | ||

| Language | Intercept | 0.23 | 0.4 | 5.07 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.31 | |

| 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.27 | 4.41 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.15 | ||

| Visibility | Intercept | 0.15 | 0.05 | 3.06 | 0.002 | 0.05 | 0.24 | |

| 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 2.86 | 0.005 | 0.34 | 0.06 | ||

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | SE | beta | t | p | LL | UL |

| Intercept | 1.74 | 0.15 | 11.42 | <0.001 | 1.44 | 2.03 | |

| Accessibility language | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 3.58 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.11 |

| Accessibility visibility | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 3.52 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.11 |

| Self-concept action S1 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 6.24 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.51 |

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | SE | beta | t | p | LL | UL |

| Intercept | 1.71 | 0.17 | 10.13 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 2.05 | |

| Accessibility language | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0.40 | 0.48 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.25 |

| Accessibility visibility | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 1.96 | 0.051 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| Self-concept action S1 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 3.31 | 0.001 | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| Self-concept language S1 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 1.81 | 0.071 | −0.01 | 0.27 |

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | SE | beta | t | p | LL | UL |

| Intercept | 1.82 | 0.15 | 12.08 | <0.001 | 1.53 | 2.12 | |

| Accessibility visibility | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.36 | 6.49 | <0.001 | 0.51 | 0.27 |

| Self-concept visibility S1 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 5.52 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 0.44 |

| SCEI 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Language | Visibility | ||

| SCEI 1 | Action | ** | * | |

| Language | -- | |||

| Visibility | ** | |||

| Accessibility | Action | |||

| Language | ** | ** | ||

| Visibility | ** | -- | ** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graichen, M.; Mikelskis-Seifert, S.; Hinderer, L.; Scharenberg, K.; Rollett, W. Unveiling Potential: Fostering Students’ Self-Concepts in Science Education by Designing Inclusive Educational Settings. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060632

Graichen M, Mikelskis-Seifert S, Hinderer L, Scharenberg K, Rollett W. Unveiling Potential: Fostering Students’ Self-Concepts in Science Education by Designing Inclusive Educational Settings. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(6):632. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060632

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraichen, Martina, Silke Mikelskis-Seifert, Linda Hinderer, Katja Scharenberg, and Wolfram Rollett. 2024. "Unveiling Potential: Fostering Students’ Self-Concepts in Science Education by Designing Inclusive Educational Settings" Education Sciences 14, no. 6: 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060632

APA StyleGraichen, M., Mikelskis-Seifert, S., Hinderer, L., Scharenberg, K., & Rollett, W. (2024). Unveiling Potential: Fostering Students’ Self-Concepts in Science Education by Designing Inclusive Educational Settings. Education Sciences, 14(6), 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060632