Abstract

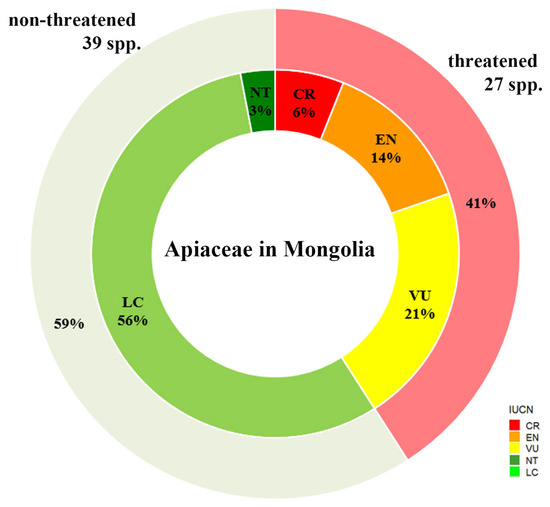

The family Apiaceae, distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere, is the largest family of angiosperms. However, little is known about the conservation status, diversity, and distribution of Apiaceae species in Mongolia. This study had two main aims: (1) to assess the national status of Apiaceae species under IUCN Red List Criterion B; (2) to evaluate the species diversity and richness of Apiaceae across Mongolia. We utilized ConR packages to assess the national Red List status of all known Mongolian Apiaceae species by analyzing their most comprehensive occurrence records. The results indicated that 27 species were classified as threatened, including 4 Critically Endangered (CR), 9 Endangered (EN), and 14 Vulnerable (VU) species. Meanwhile, 39 species were assessed as non-threatened, with 2 Near Threatened (NT) species and 37 species of Least Concern (LC). Furthermore, detailed distribution maps for 66 Apiaceae species in Mongolia were presented. We assessed the species diversity and Shannon and Simpson diversity indices of Apiaceae by analyzing all occurrence records using the iNext package. Overall, the Hill diversity estimates indicate that the sampling conducted in Mongolia adequately captured species occurrences. For species pattern analysis, we examined the species richness, weighted endemism, and the corrected weighted endemism index using Biodiverse v.4.1 software. Mongolia was portioned into 715 grid cells based on 0.5° × 0.5° grid sizes (equivalent to approximately 50 × 50 km2). There was a total of 3062 unique occurrences of all Apiaceae species across Mongolia. In the species richness analysis, we identified 10 grids that exhibited high species richness (18–29 species) and 36 grids with 11–17 species. For genus richness, we observed seven grids that exhibited a high genus richness of 16–22 genera. Furthermore, we analyzed species richness with a specific focus on threatened species, encompassing CR, EN, and VU species throughout Mongolia. A total of 92 grids contained at least one threatened species. There were six grids that had two to five threatened species, which were adequately covered by protected areas in western Mongolia. Overall, our results on species richness and conservation status will serve as important foundational research for future conservation and land management efforts in Mongolia.

1. Introduction

Biodiversity hotspot and gap analyses are standard approaches for identifying priority areas for species conservation. Hotspots are defined as either the most important sites in terms of species diversity or sites where the most threatened or endemic species occur [1]. In recent years, a number of publications have focused on species pattern diversity, using species occurrence records at both global and regional scales [2,3,4]. Additionally, several studies have focused on specific families [5,6] or genera [7,8,9].

Assessing the IUCN Red List status of a species is important for establishing conservation priorities [4,10]. Since 2011, approximately 640 species (representing 21% of the 3041 native taxa based on [11]) of vascular plants have been evaluated using regional red lists in Mongolia [6,12,13,14]. Among these, 390 and 250 species were classified as threatened (Critically Endangered, Endangered, and Vulnerable) and non-threatened (Near Threatened, Least Concern and Data Deficient), respectively. Most of the assessed species have been evaluated by committee members, such as botanists, in Mongolia [12,14]. However, owing to limited data capture and field survey efforts, representative sizes of the extent of occurrence (EOO) and area of occupancy (AOO) of most species remain lacking. For example, the EOO and AOO have been determined for only 5% of Red Listed species using GeoCAT [13] and ConR [6]. Overall, 79% of vascular plants in Mongolia have not been evaluated at the national level.

The family Apiaceae is the largest family of angiosperms, and it is widely distributed in the temperate zones of both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere [15]. It has considerable species diversity, primarily being concentrated in Central Asian countries [16,17,18,19,20]. This family comprises 466 genera and approximately 3800 species, which include many important vegetables and medicinal plants [21,22]. Mongolia is renowned for its diverse landscapes, ranging from the Gobi Desert to mountainous regions, where a variety of plant species have adapted to thrive in different environmental conditions [21]. The flora of Mongolia exhibits remarkable adaptability to the harsh climatic conditions of Mongolia, which are characterized by extreme temperatures, aridity, and high altitudes [22]. To date, a total of 3041 native vascular taxa, belonging to 653 genera and 111 families, have been identified in Mongolia [11].

Apiaceae is one of the largest families in the flora of Mongolia [11]. The first comprehensive checklist of Apiaceae was published by Grubov [23] and included 46 species and 26 genera in Mongolia. A taxonomic revision of Apiaceae with identification keys and regional distribution was provided by Urgamal [24]. Recently, Pimenov [18] updated and revised the Chinese Apiaceae, which included and discussed the majority of the Mongolian Apiaceae species. To date, a total of 66 native taxa belonging to 36 genera in the Apiaceae family have been recognized according to the latest checklist of native Mongolian vascular plants [11]. In addition, three non-native Apiaceae species are found in Mongolia: Anethum graveolens L., Eryngium planum L., and Pastinaca sativa L. [11]. Of all the Mongolian Apiaceae, eight species are categorized as subendemic to Mongolia because they co-occur in Russia and China [11]. To date, no Apiaceae species have been identified as endemic to Mongolia [6].

Apiaceae species have previously been assessed at the national level using the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Categories and Criteria [12,14]. In addition, the distribution maps of several species have been updated recently [25,26]. However, numerous important species, especially those of medicinal value, have not been evaluated using Red List Categories at the national level. Furthermore, the species diversity and richness of Mongolian Apiaceae have not been evaluated to date because of incomplete species occurrence data. Therefore, our study aimed to (1) analyze Apiaceae species richness using data from all known locations across Mongolia; (2) assess the national IUCN Red List status of all Mongolian Apiaceae species using Criterion B; and (3) determine the diversity of threatened Apiaceae species in Mongolian protected areas.

2. Results

2.1. Conservation Assessment and Distribution

The national IUCN Red List statuses of the 66 taxa were evaluated under Criterion B at the national level (Figure 1, Table A1). Among these, 27 taxa were classified as threatened, including 4 Critically Endangered (CR), 9 Endangered (EN), and 14 Vulnerable (VU) species. The remaining 39 species were assessed as non-threatened, comprising 2 Near-Threatened (NT) species and 37 species of Least Concern (LC).

Figure 1.

The national Red List statuses of Apiaceae species in Mongolia according to IUCN Criterion B.

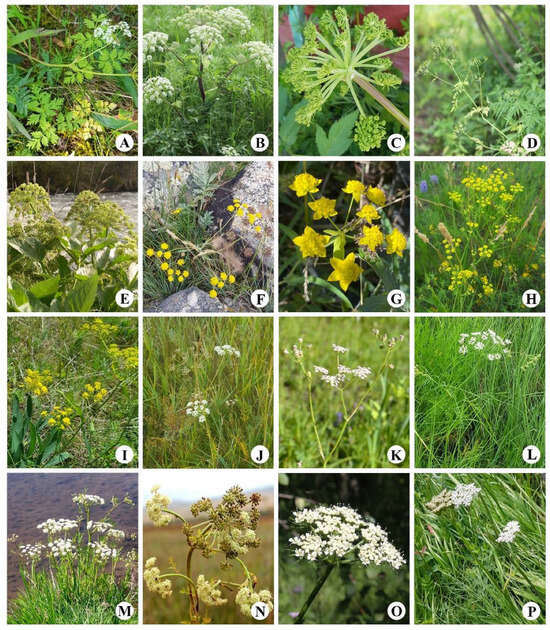

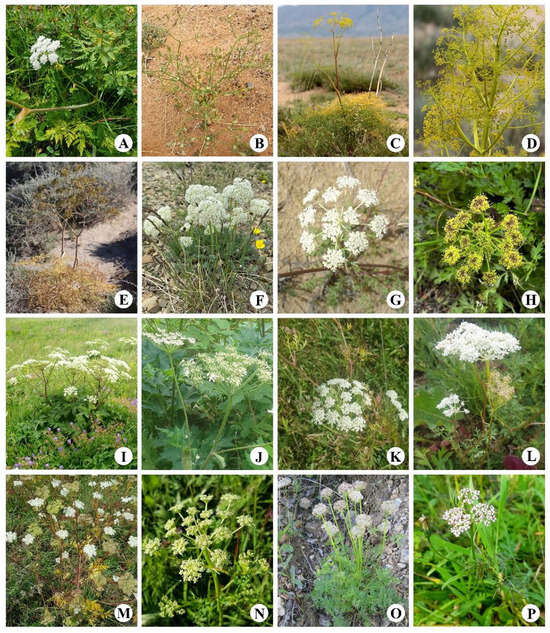

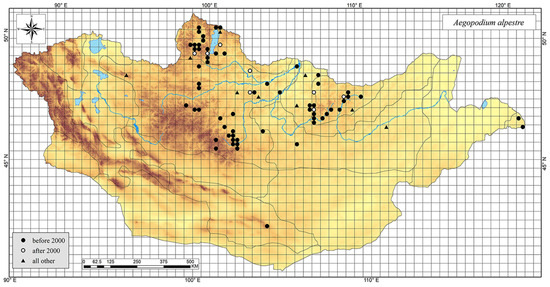

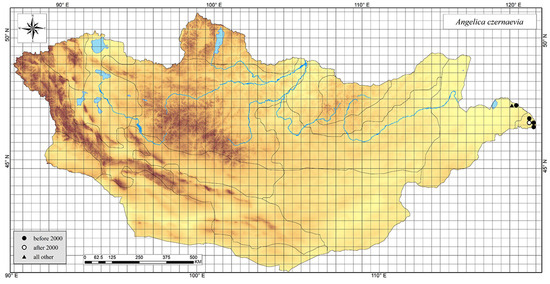

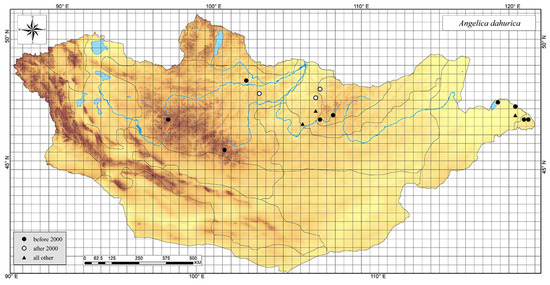

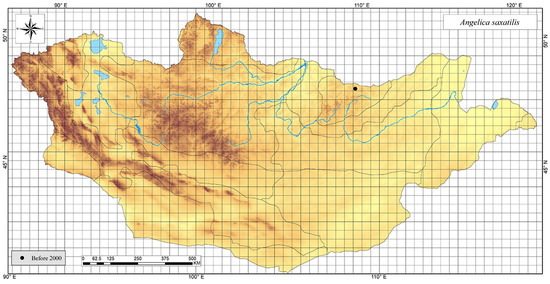

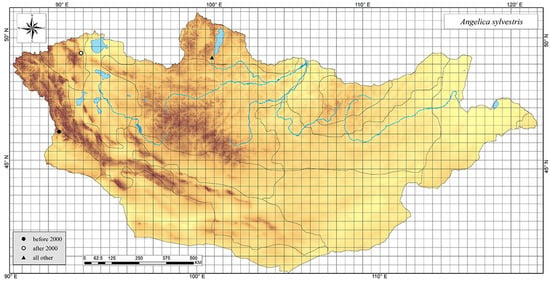

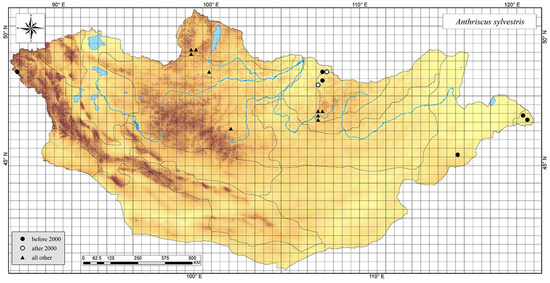

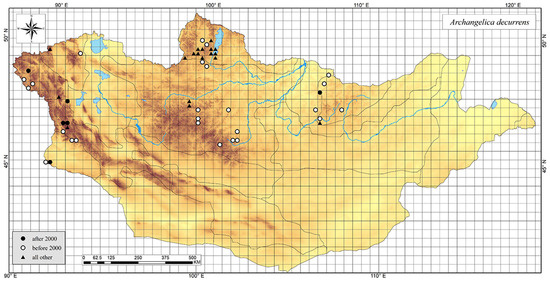

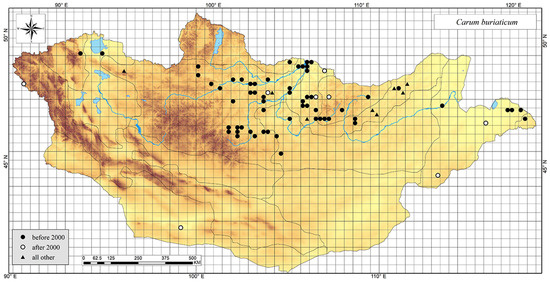

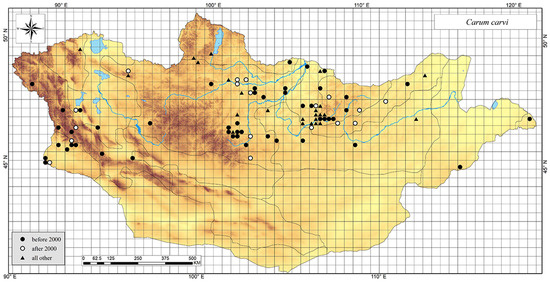

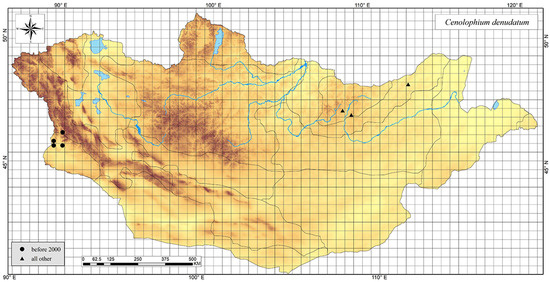

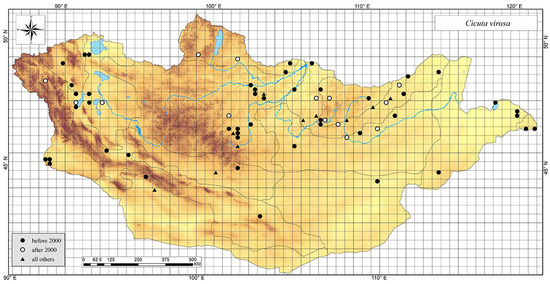

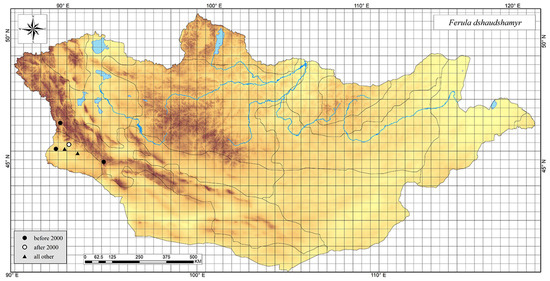

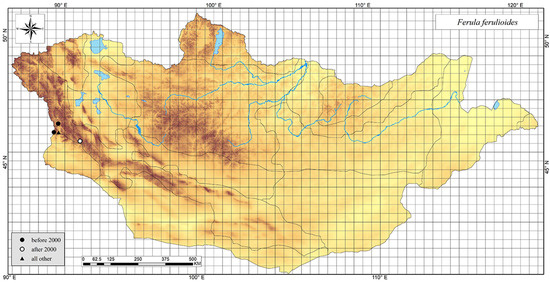

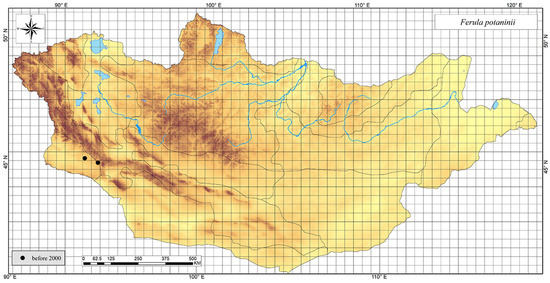

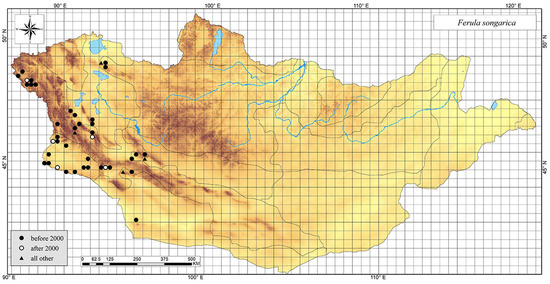

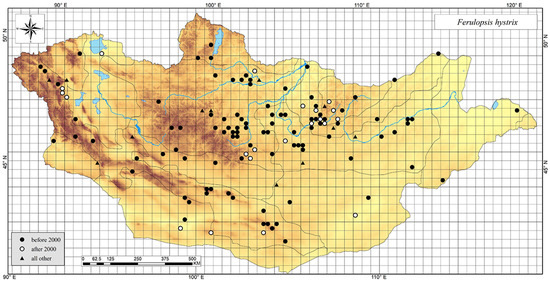

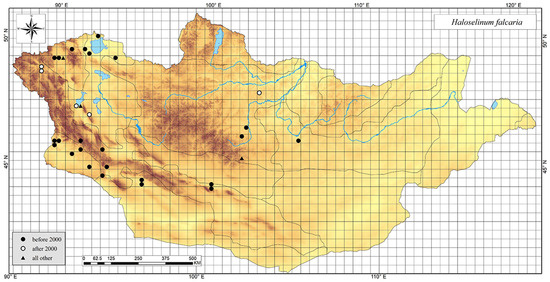

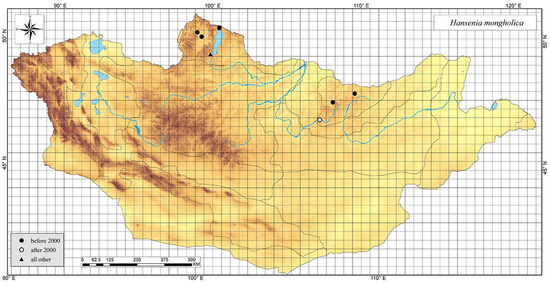

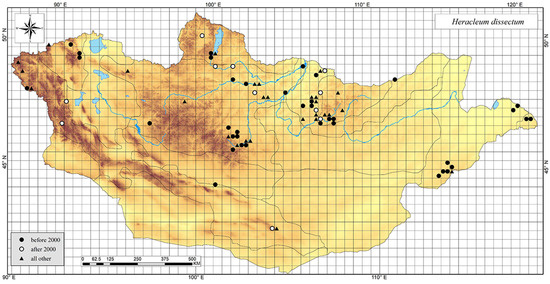

We obtained high-quality photographs of these species from our own field surveys and the iNaturalist platform (Appendix B, Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3). Approximately 90% of all species were adequately photographed in Mongolia. In addition, we generated distribution maps for 66 taxa based on all occurrences, as shown in the Appendix C (Figure A4, Figure A5, Figure A6, Figure A7, Figure A8, Figure A9, Figure A10, Figure A11, Figure A12, Figure A13, Figure A14, Figure A15, Figure A16, Figure A17, Figure A18, Figure A19, Figure A20, Figure A21, Figure A22, Figure A23, Figure A24, Figure A25, Figure A26, Figure A27, Figure A28, Figure A29, Figure A30, Figure A31, Figure A32, Figure A33, Figure A34, Figure A35, Figure A36, Figure A37, Figure A38, Figure A39, Figure A40, Figure A41, Figure A42, Figure A43, Figure A44, Figure A45, Figure A46, Figure A47, Figure A48, Figure A49, Figure A50, Figure A51, Figure A52, Figure A53, Figure A54, Figure A55, Figure A56, Figure A57, Figure A58, Figure A59, Figure A60, Figure A61, Figure A62, Figure A63, Figure A64, Figure A65, Figure A66, Figure A67, Figure A68, Figure A69 and Figure A70). Based on the distribution map results, the majority of the species were collected prior to 2000. Finally, we identified several new locations of Apiaceae species for the phytogeographical regions which are marked as plus (Appendix A).

2.2. Distribution Patterns of Species Richness

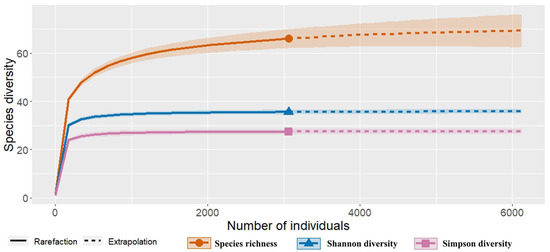

We assessed the species diversity and Shannon and Simpson diversity indices of Apiaceae based on all occurrence records. In general, the Hill diversity estimates indicated that the sampling conducted in Mongolia adequately covered species occurrence (Figure 2). According to the rarefaction curve, the numbers of both the species and individuals were sufficient, as indicated by the saturated lines of the Shannon (blue) and Simpson (pink) diversity indices (Figure 2). However, the species richness (orange line) exhibited a slight tendency to increase with the number of individuals.

Figure 2.

The species occurrences of the family Apiaceae in Mongolia. The shading surrounding the line corresponds to 95% confidence intervals.

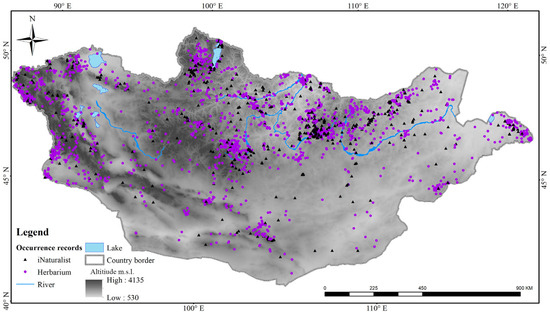

A total of 3062 unique records were obtained, including 2015 and 1047 records from herbaria and the iNaturalist platform, respectively (Figure 3). The majority of occurrences were in mountainous areas of Mongolia such as the Altai, Khangai, Khentii and Khuvsgul mountains. Most records were from mountain steppe, forest steppe, and steppe habitats.

Figure 3.

The species occurrences of Apiaceae in Mongolia.

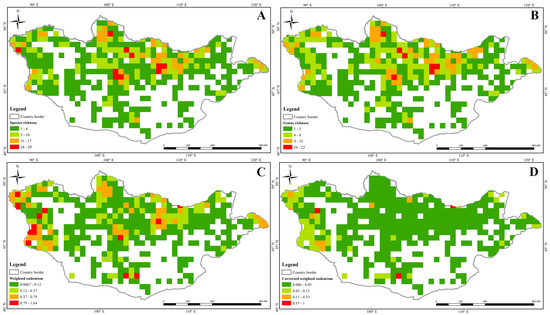

Of the 715 grid cells covering Mongolia, 408 contained at least one species record. We calculated the SR, WE, and CWE for all occurrences across Mongolia. Our data collection was highly comprehensive because of our exhaustive search of all available data sources. According to the SR parameter, all species were unevenly distributed throughout the country, except in the southern and western regions (Figure 4A). We identified 10 grid cells that exhibited a high level of species richness, each containing 18–29 Apiaceae species. In addition, we identified 36 grid cells with 11–17 species (Figure 4A). We also considered genus richness: seven grids had high genus richness, with 16–22 genera in each grid (Figure 4B). Twelve grid cells had high WE; these were distributed in the Mongolian Altai, Khentii, Khangai, and Gurvan Saikhan mountain ranges (Figure 4C). Only three cells featuinf a high CWE index were identified, and these were scattered throughout the Khentii, Jargalant Khairkhan, and Gurvan Saikhan mountain ranges (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Indicators of the species diversity of Apiaceae in Mongolia. (A) Species richness; (B) genus richness; (C) weighted endemism; (D) corrected weighted endemism.

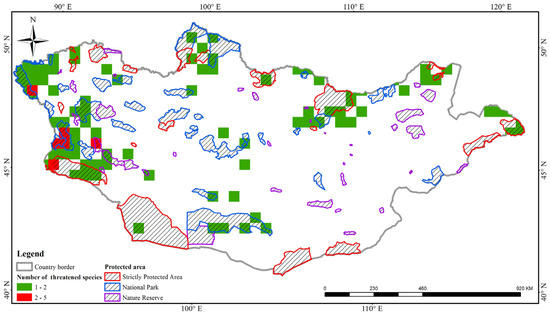

In addition, we examined the species diversity of threatened Apiaceae species overlapping with all protected areas in Mongolia. A total of 92 grid cells contained at least one threatened species. Among these, six grid cells had two to five threatened Apiaceae species that occurred in the Altai-Dzungarian mountain range of Mongolia (Figure 5). The majority of the threatened species richness was covered by formally protected areas or national parks (Figure 5). For example, the grid cells containing two to five threatened Apiaceae species were distributed within the Great Gobi B, Altai Tavan Bogd, and Bulgan-Gol Ikh Ongog national parks in western Mongolia (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Overlap between threatened species richness (comprising CR, EN, and VU species) and protected areas in Mongolia.

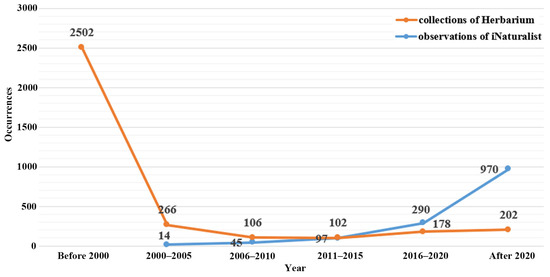

We compared the herbarium data and iNaturalist observations of Apiaceae, focusing on the collection period (Figure 6). The majority of herbarium specimens were collected prior to 2000, with relatively few collections being made since. However, the number of iNaturalist observations is increasing each year because of the number of citizen scientists uploading photo observations to the Flora of Mongolia project (https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/flora-of-mongolia, accessed on 12 March 2024).

Figure 6.

The number of occurrences of Apiaceae species in Mongolia collected from herbariums and the iNaturalist.

3. Discussion

The Red List serves as a valuable tool for conservation planning and decision making. It helps governments, NGOs, and other stakeholders identify areas and species in need of protection, as well as to develop conservation strategies and policies [27]. In addition, the Red List is a crucial tool for assessing the status of species worldwide, guiding conservation action by informing prioritization processes and promoting the conservation of biodiversity for future generations. Therefore, several previous publications have assessed the conservation status of vascular plants at the global level using Criterion B [4,9,28,29]. In this study, we evaluated the national conservation status of all Apiaceae species using the ConR package in accordance with IUCN Criterion B. An advantage of Criterion B is that can be used to assess the status of species with unknown population sizes or rates of decline.

In recent decades, a number of researchers have been conducting species pattern analyses on various plants groups in the world. This is because species richness analyses help to inform the future conservation and management of protected areas and land, respectively [3,4]. However, only a few studies have applied species richness analyses and conservation status assessments to vascular plants and fungi in Mongolia [30,31]. For example, Baasanmunkh et al. [30] studied the diversity of Orchidaceae, for which a number of high diversity grids are not covered by protected areas. In this study, we analyzed the species patterns of Apiaceae using three different indices. In general, our data collection was the most comprehensive because of our exhaustive search of all available data sources. Based on species pattern analysis, we identified four highly diverse hotspots in the central, western, and northern parts of Mongolia (Figure 4A). In addition, we performed species richness analyses solely for threatened species, such as CR, EN, and VU species, in accordance with our own recently developed assessments (Figure 4). Fortunately, the majority of the threatened species richness was covered by formally protected areas or national parks (Figure 4). For example, two to five threatened Apiaceae species were distributed within the Great Gobi B, Altai Tavan Bogd, and Bulgan-Gol Ikh Ongog national parks in western Mongolia (Figure 4). Our results on species richness and conservation status, along with those on Orchidaceae [30] and fungi [31], are important fundamental pieces of research for future conservation and land management efforts in Mongolia.

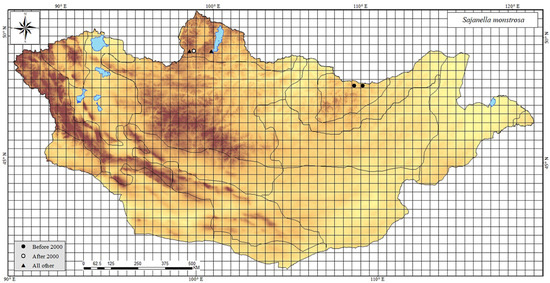

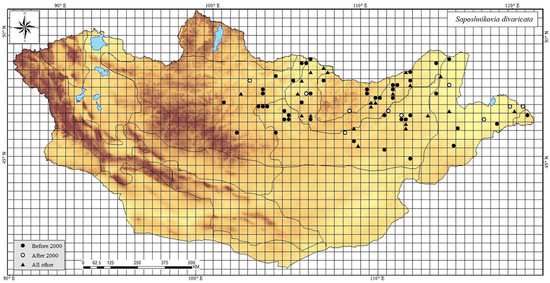

Interestingly, we found additional occurrence records for several threatened species that had previously been noted in only one or a few locations in Mongolia. For example, the nationally Endangered Sajanella monstrosa (Willd.) Soják was previously known only in the Khentei region of northern Mongolia; however, we discovered it in the Khuvsgul region in north-western Mongolia in 2020 [27]. Furthermore, several important medicinal Apiaceae species have been identified in Mongolia. For instance, Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk. (Apiaceae) is a widely recognized traditional medicinal plant [32], but its distribution is decreasing because of illegal collection. It should be noted that most records are from prior to 2000, with there being a minimal number of recent collections. This could be attributed to the potential extinction of numerous individuals in the wild due to climate change or overgrazing across Mongolia. If it is indeed the case that some occurrence records are now obsolete due to species becoming locally extirpated, we may have overestimated EOO and/or AOO for some species, resulting in species being assigned a lower threat status than they deserve in reality. Thus, the status of the Apiaceae species in Mongolia could be worse than is currently believed. Hopefully, this will become clearer as the number of citizen scientists increases.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

Occurrence data for each species were gathered from several sources: (1) our field data collected over 15 years; (2) available herbarium data from ALTB, E, GAT, GFW, HAL, INM, K, LE, MW, MEL, NS, NSK, OSBU, PL, UBA, UBU, and US [33]; (3) the Flora of Mongolia project on the iNaturalist platform (https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/flora-of-mongolia, accessed on 12 March 2024); (4) the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) platform and the Virtual Guide to Mongolia [34,35]. We collected data on approximately 4752 occurrences of Apiaceae in Mongolia. Among these, over 2000 occurrences are not available online, being stored in the UBA and UBU herbariums in Mongolia. We recorded 4752 occurrences of Apiaceae taxa based on all available data. We subsequently removed 1690 duplicate and non-georeferenced records. In total, 3062 occurrences were analyzed.

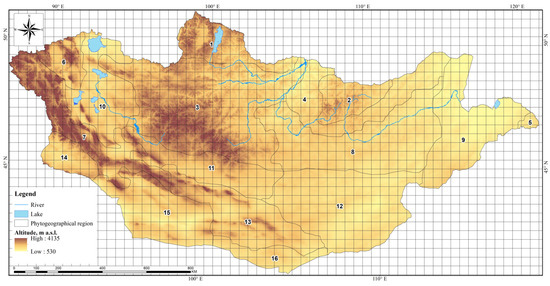

For the species distribution mapping, we used topographic maps depicting phytogeographical regions and an altitude range of approximately 520–4300 m a.s.l. (Figure A4) based on [25]. This distribution map was derived from [11,25], with modifications. Distribution points are represented by three different symbols, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mapping symbols used in the distribution maps.

4.2. Conservation Status Assessment

Taxa were assessed under Red List Criterion B in accordance with the IUCN national Red List guidelines [36]. Criterion B uses geographic range (EOO or AOO) and evidence of population decline, fragmentation, or fluctuations to assess extinction risk. The EOO and AOO were estimated using the ConR package [37] in R v.4.0.4 programming software [38]. The AOO was estimated based on a user-defined grid cell of 2 km2, as recommended by the IUCN [29]. We did not assess the three non-native Apiaceae species found in Mongolia.

4.3. Distribution Patterns of Species Richness

First, we analyzed Hill numbers (including q = 0, 1, and 2) using the iNEXT package [39]. For instance, the Hill number q = 0 corresponds to species richness, q = 1 reflects the effective number of species (which is the exponent of Shannon diversity), and q = 2 denotes the number of dominant species (inverse Simpson diversity; [40]). Second, we created a grid net for Mongolia with a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° grid size (equivalent to approximately 50 × 50 squares) using the FishNet tool in ArcGIS 10.3 [41]. Mongolia was partitioned into 715 grid cells. We estimated three diversity indices (species richness (SR), weighted endemism (WE), and corrected weighted endemism (CWE)) using Biodiverse v.4.1 software [42]. WE is estimated by considering the presence or absence of a species within a cell, whereas CWE is determined by calculating the proportion of endemic species within a cell in relation to the total endemic species richness of the cell [42]. Furthermore, we used geographic information system data regarding protected areas obtained from the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA; https://protectedplanet.net/, accessed on 12 March 2024) to determine the extent to which threatened species were covered by protected areas. We excluded natural monuments, a category of protected areas in Mongolia, because they are typically geographically restricted to small areas and primarily focus on preserving historical and cultural heritage.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the national Red List statuses of 66 taxa in Mongolia according to IUCN Criterion B, shedding light on the conservation statuses of these species. Our findings revealed that a significant portion of these taxa, totaling 27 and 39 species, are classified as threatened and non-threatened, respectively. Our efforts resulted in comprehensive distribution maps for all 66 taxa. Moreover, our study assessed species diversity and distribution across Mongolia, utilizing various diversity indices and occurrence records. Notably, we identified several high biodiversity hotspots, particularly in mountainous areas such as the Altai, Khangai, Khentii, and Khuvsgul mountains. Finally, we compared herbarium data and iNaturalist observations of Apiaceae, revealing interesting trends in collection periods and observation frequencies. While herbarium specimens were predominantly collected before 2000, the number of iNaturalist observations has been steadily increasing since then, indicating the growing contribution of citizen scientists to biodiversity research. Overall, our study provides valuable insights into the conservation status, distribution patterns, and biodiversity of Apiaceae species in Mongolia, laying a foundation for targeted conservation efforts and further research endeavors in the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.; methodology, S.B.; software, S.B. and Z.T.; formal analysis, S.B. and Z.T; investigation, S.B. and M.U.; resources, M.U., C.J. and B.O.; data curation, M.U. and B.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, S.B., M.U., S.-X.Y., M.G.W.C. and H.J.C.; supervision, S.B. and H.J.C.; project administration, H.J.C.; funding acquisition, H.J.C. and J.-W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Korea National Arboretum (Grant Number: KNA1-2-42, 22-2), Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant No. 2023R1A6C101B022), and the Foundational and Protective Field of Studies Support Project at Changwon National University in 2024.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the IUCN. The designation of geographical entities in this paper and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Annotated Checklist of the Apiaceae Family with Conservation Status and Regional Distribution

Table A1.

Annotated checklist of the Apiaceae family with conservation status and regional distribution.

Table A1.

Annotated checklist of the Apiaceae family with conservation status and regional distribution.

| No | Accepted Taxon Name | Number of Records | EOO km2 | AOO km2 | Threat Category and Criteria in This Study | Previous Threat Category with Reference | Phytogeographical Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aegopodium alpestre Ledeb. | 128 | 562,142 | 428 | LC | - | 1–5, 8+, 13 |

| 2 | Angelica czernaevia (Fisch and C.A.Mey.) Kitag. | 8 | 2894 | 32 | VU B1a+B2a | - | 5, 9 |

| 3 | Angelica dahurica (Hoffm.) Benth. and Hook.f. | 21 | 302,422 | 68 | LC | - | 2–5,9 |

| 4 | Angelica saxatilis Turcz. | 1 | 4 | CR B2a | - | 2 | |

| 5 | Angelica sylvestris L. | 5 | 153,400 | 16 | VU B2a | - | 1+, 6, 7 |

| 6 | Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) Hoffm. | 22 | 398,896 | 76 | LC | - | 1–5, 7, 9 |

| 7 | Archangelica decurrens Ledeb. | 69 | 587,817 | 244 | LC | - | 1–4, 6, 7, 14 |

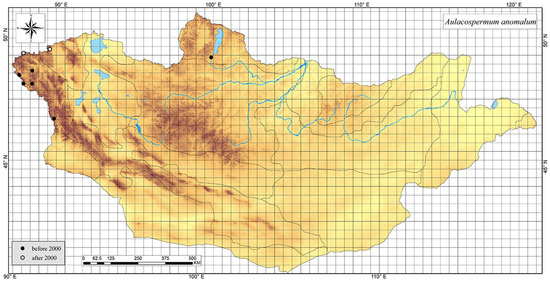

| 8 | Aulacospermum anomalum Ledeb. | 8 | 145,059 | 32 | VU B2a | EN [14] | 6, 7 |

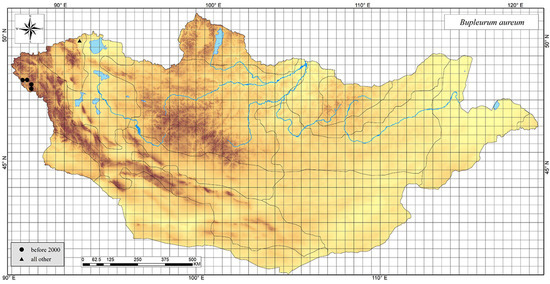

| 9 | Bupleurum aureum Fisch. ex Hoffm. | 7 | 10,118 | 20 | EN B2a | - | 7 |

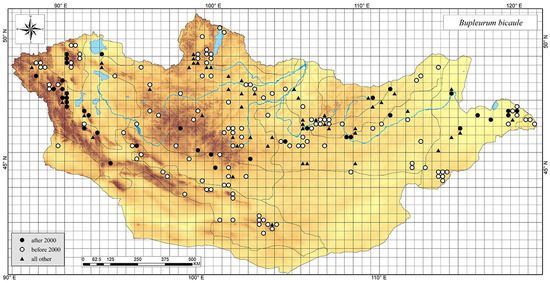

| 10 | Bupleurum bicaule Helm. | 294 | 1,401,721 | 1040 | LC | - | 1–13, 14+ |

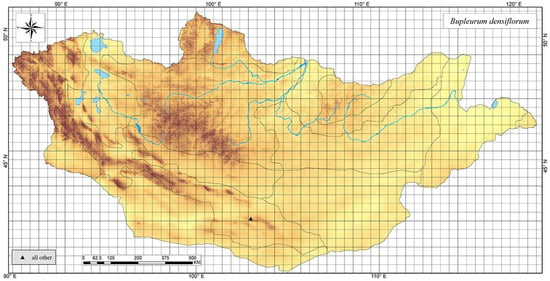

| 11 | Bupleurum densiflorum Rupr. | 1 | 4 | CR B2a | - | 7+, 13+, 14+ | |

| 12 | Bupleurum krylovianum Schischk. (SE) | 7 | 48,101 | 24 | VU B2a | - | 3, 7 |

| 13 | Bupleurum multinerve DC. | 54 | 518,858 | 196 | LC | - | 1–7, 9, 11 |

| 14 | Bupleurum scorzonerifolium Willd. | 213 | 1,096,567 | 664 | LC | - | 1–6, 8, 9, 12, 13 |

| 15 | Bupleurum sibiricum Vest. | 60 | 413,268 | 204 | LC | - | 2–4, 8, 9 |

| 16 | Carum buriaticum Turcz. | 107 | 1,115,103 | 376 | LC | - | 1–6, 8, 9 |

| 17 | Carum carvi L. | 151 | 972,274 | 464 | LC | - | 1–10, 14 |

| 18 | Cenolophium denudatum (Hornem.) Tutin. | 11 | 108,196 | 28 | VU B2a | NT [14] | 2+, 4+, 7, 10, 14 |

| 19 | Cicuta virosa L. | 83 | 1,183,666 | 296 | LC | - | 1–15 |

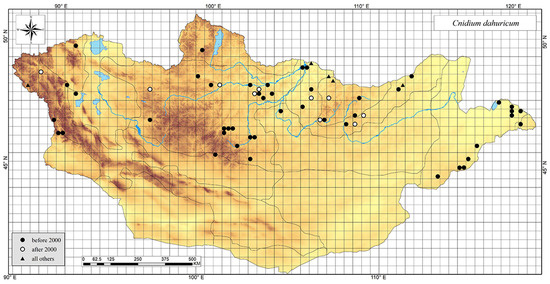

| 20 | Cnidium dauricum (Jacq.) Turcz. | 74 | 896,555 | 276 | LC | - | 1+, 2–10 |

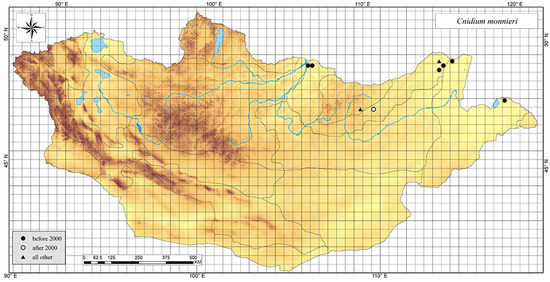

| 21 | Cnidium monnieri Cusson. | 9 | 137,823 | 36 | VU B2a | - | 2+, 4, 9 |

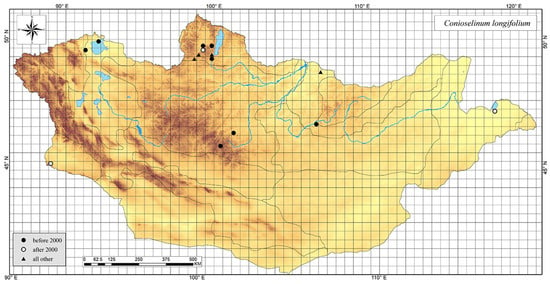

| 22 | Conioselinum longifolium Turcz. (SE) | 16 | 613,699 | 64 | LC | - | 1, 2, 4, 9, 10, 14+ |

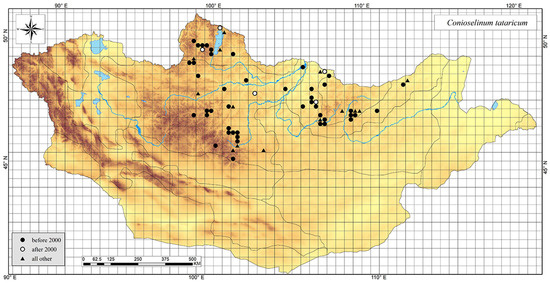

| 23 | Conioselinum tataricum Hoffm. | 96 | 362,294 | 344 | LC | - | 1–4 |

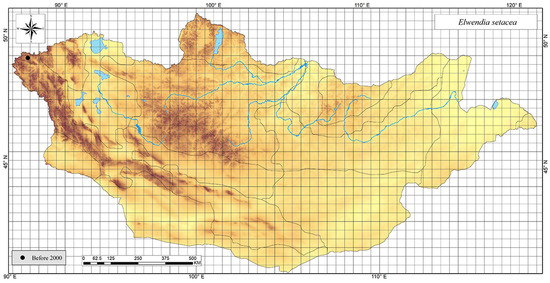

| 24 | Elwendia setacea (Schrenk) Pimenov and Kljuykov. | 1 | 4 | CR B2a | EN [14] | 7 | |

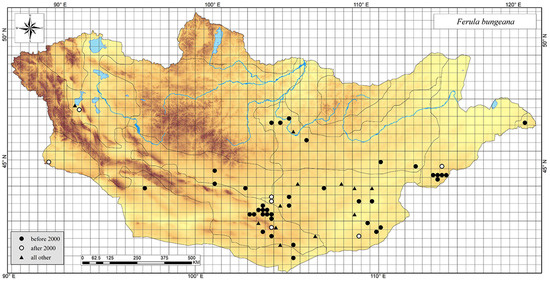

| 25 | Ferula bungeana Kitag. (SE) | 77 | 885,091 | 288 | LC | - | 8–16 |

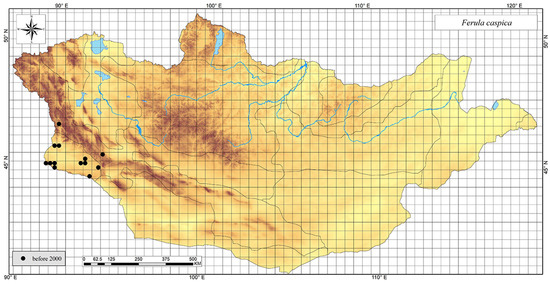

| 26 | Ferula caspica M.Bieb. | 17 | 33,037 | 64 | NT B1a+B2a | - | 7, 14 |

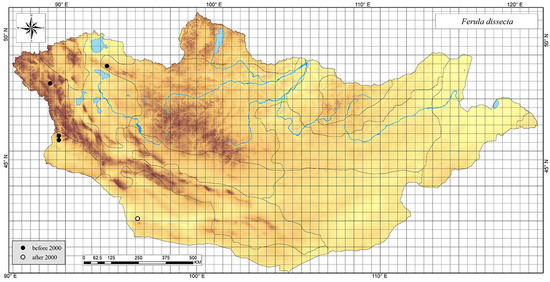

| 27 | Ferula dissecta Ledeb. | 5 | 134,334 | 20 | EN B2a | - | 3, 7, 14, 15+ |

| 28 | Ferula dshaudshamyr Korovin. | 7 | 13,241 | 24 | VU B1a+B2a | - | 7, 14 |

| 29 | Ferula ferulioides (Steud.) Korovin. | 11 | 4611 | 32 | EN B2a | EN [12] | 7 |

| 30 | Ferula potaninii Korovin. | 2 | 8 | EN B2a | - | 14 | |

| 31 | Ferula songarica Pall. ex Willd. | 53 | 257,441 | 204 | LC | - | 3, 7, 10, 14, 15+ |

| 32 | Ferulopsis hystrix (Bunge) Pimenov. (SE) | 165 | 1,393,906 | 616 | LC | - | 1+, 2–4, 6–15 |

| 33 | Haloselinum falcaria (Turcz.) Pimenov. (SE) | 35 | 528,427 | 136 | LC | - | 3, 6–8, 10, 11, 13–15 |

| 34 | Hansenia mongholica Turcz. (SE) | 9 | 286,325 | 36 | VU B2a | - | 1, 2 |

| 35 | Heracleum dissectum Ledeb. | 146 | 1,299,977 | 420 | LC | - | 1–7, 9, 13 |

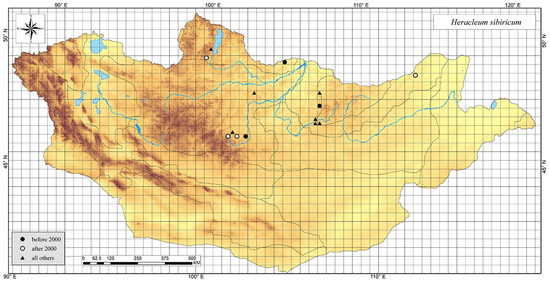

| 36 | Heracleum sibiricum L. | 24 | 316,357 | 64 | LC | - | 1–3, 4+ |

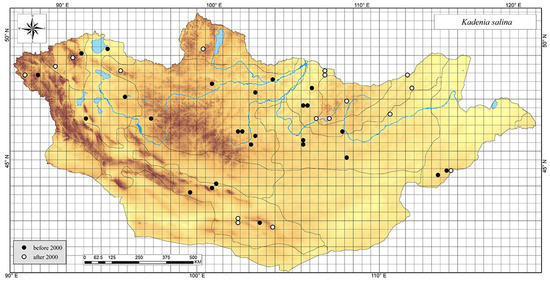

| 37 | Kadenia salina (Turcz.) Lavrova and V.N.Tikhom. | 44 | 1,010,857 | 176 | LC | - | 1+, 2–4,6+, 7–11, 13 |

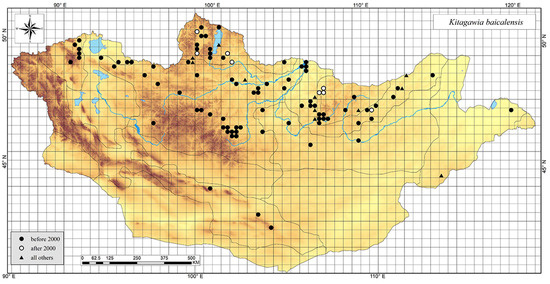

| 38 | Kitagawia baicalensis (Redow.) Pimenov. (SE) | 163 | 1,072,026 | 532 | LC | - | 1–4, 6, 8, 10, 13+ |

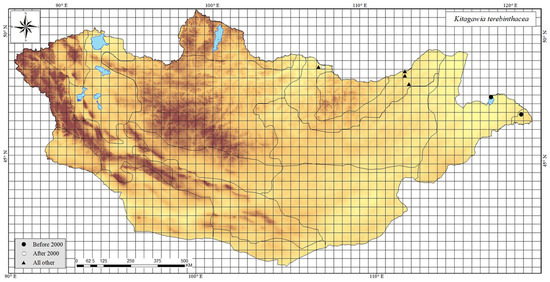

| 39 | Kitagawia terebinthacea (Fisch.) Pimenov. | 11 | 48,425 | 28 | VU B2a | VU [14] | 2, 4, 5, 9 |

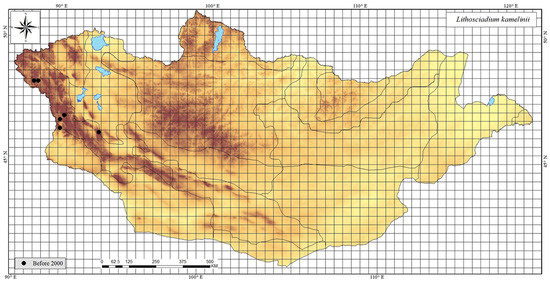

| 40 | Lithosciadium kamelinii (V.M.Vinogr.) Pimenov. (SE) | 7 | 19,856 | 28 | VU B1a+B2a | EN [14] | 7 |

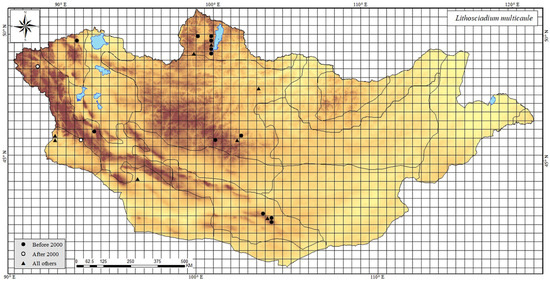

| 41 | Lithosciadium multicaule Turcz. (SE) | 33 | 596,884 | 96 | LC | - | 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 13 |

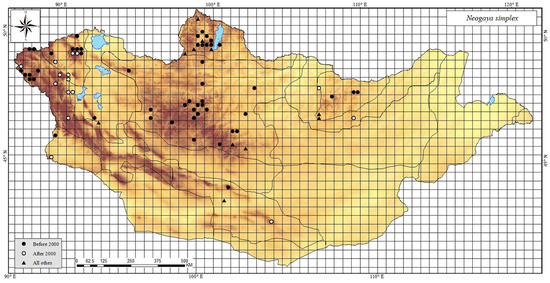

| 42 | Neogaya simplex Meisn. | 102 | 953,174 | 380 | LC | - | 1–4, 6, 7, 13, 14 |

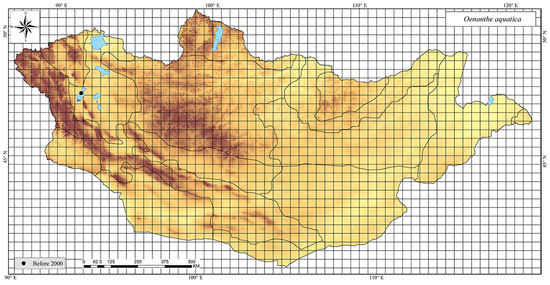

| 43 | Oenanthe aquatica (L.) Poir. | 1 | 4 | CR B2a | CR [14] | 10 | |

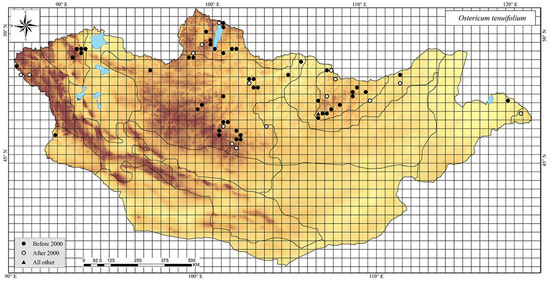

| 44 | Ostericum tenuifolium (Pall.) Y.C.Chu | 94 | 690,102 | 296 | LC | - | 1–10, 14+ |

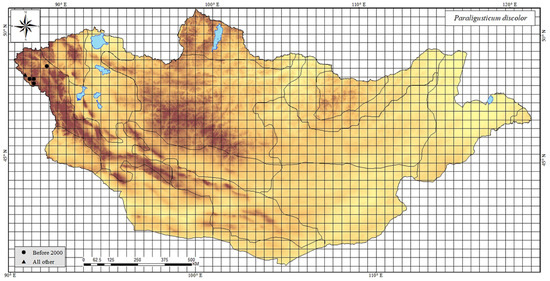

| 45 | Paraligusticum discolor (Ledeb.) V.N.Tikhom. | 7 | 2211 | 28 | EN B2a | - | 7 |

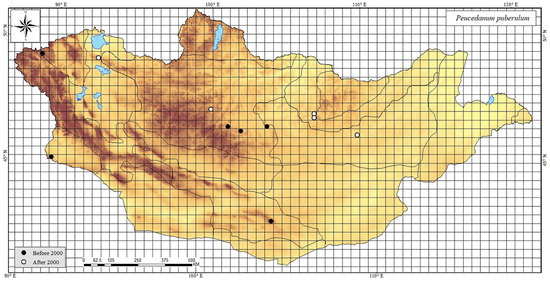

| 46 | Peucedanum puberulum Turcz. (SE) | 12 | 157,298 | 36 | VU B2a | - | 2, 3, 7+, 8, 13, 14+ |

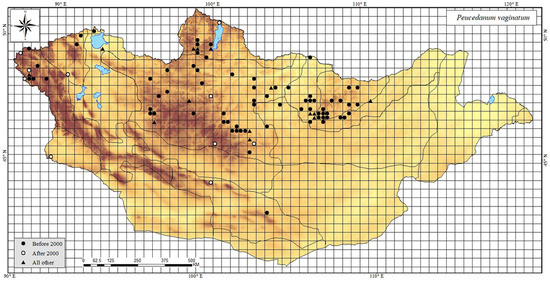

| 47 | Peucedanum vaginatum Ledeb. | 130 | 964,839 | 464 | LC | - | 1–4, 6–8, 10+, 13, 14+ |

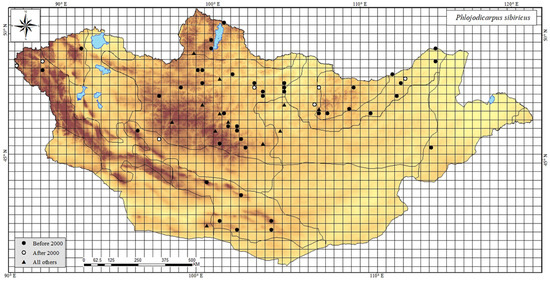

| 48 | Phlojodicarpus sibiricus Koso-Pol. | 74 | 1,201,846 | 256 | LC | - | 1–4, 6+, 7–9, 11+, 13 |

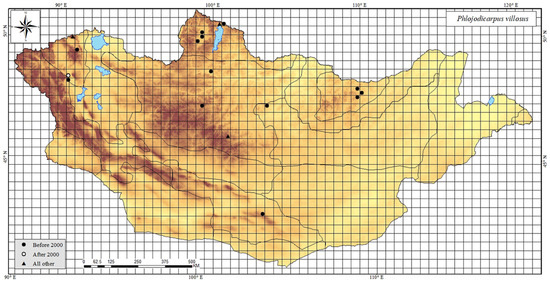

| 49 | Phlojodicarpus villosus Turcz. | 19 | 678,545 | 76 | LC | - | 1–3, 6, 7+, 13+ |

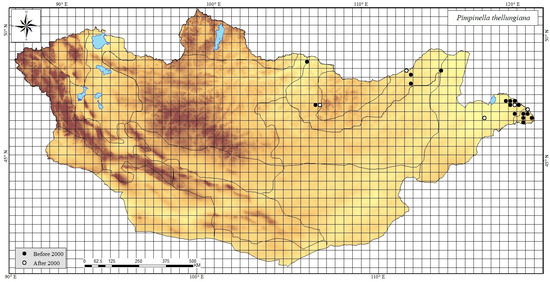

| 50 | Pimpinella thellungiana H.Wolff | 28 | 177,961 | 108 | NT B1a+B2a | - | 4, 5, 9 |

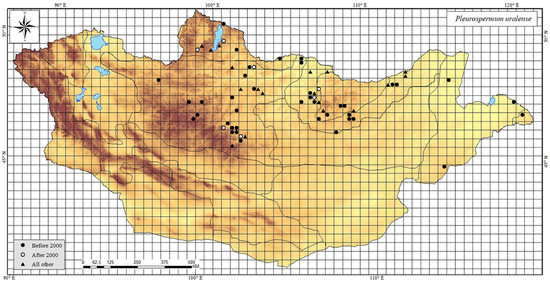

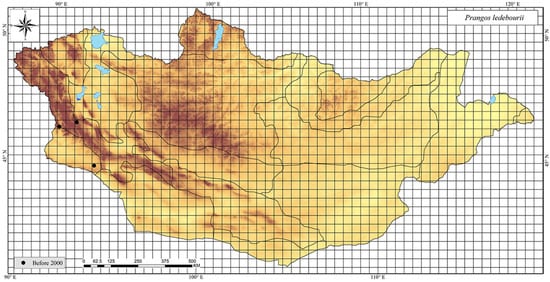

| 51 | Pleurospermum uralense Hoffm. | 106 | 639,543 | 312 | LC | - | 1–5, 8, 9 |

| 52 | Prangos ledebourii Herrnst and Heyn. | 3 | 6059 | 12 | EN B2a | - | 7, 14 |

| 53 | Sajanella monstrosa (Willd.) Soják. (SE) | 6 | 10,618 | 20 | EN B2a | EN [14] | 1+, 2 |

| 54 | Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk. | 129 | 462,209 | 392 | LC | VU [14] | 2–5, 8, 9 |

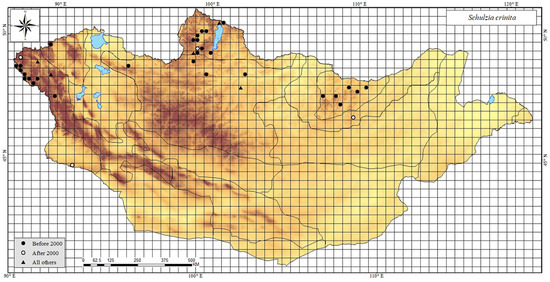

| 55 | Schulzia crinita (Pall.) Spreng. | 53 | 672,447 | 180 | LC | - | 1–4, 6, 7, 14+ |

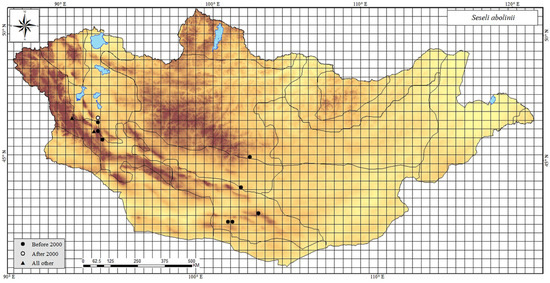

| 56 | Seseli abolinii (Korovin) Schischk. | 11 | 172,272 | 44 | VU B2a | - | 7, 10, 11, 13 |

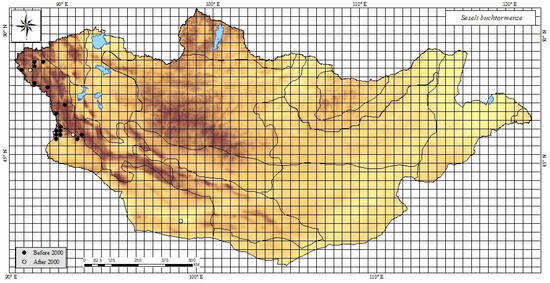

| 57 | Seseli buchtormense W.D.J.Koch | 26 | 107,933 | 104 | LC | - | 7, 14, 15+ |

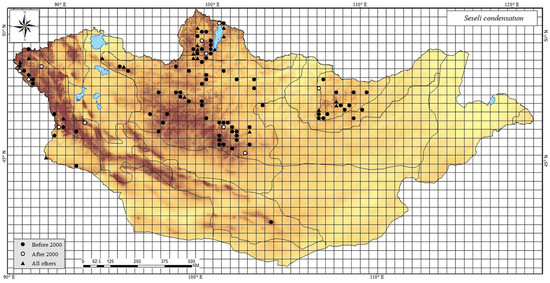

| 58 | Seseli condensatum Rchb.f. | 155 | 956,132 | 508 | LC | - | 1–3, 4+, 7–8, 13+, 14 |

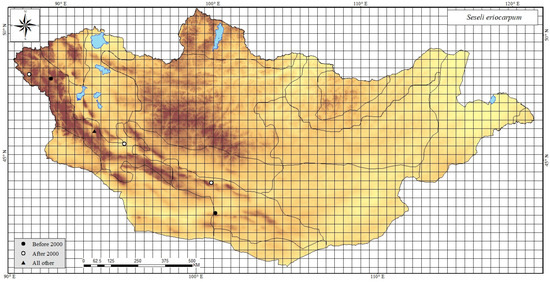

| 59 | Seseli eriocarpum B.Fedtsch. | 6 | 80,862 | 24 | VU B2a | - | 7, 13+ |

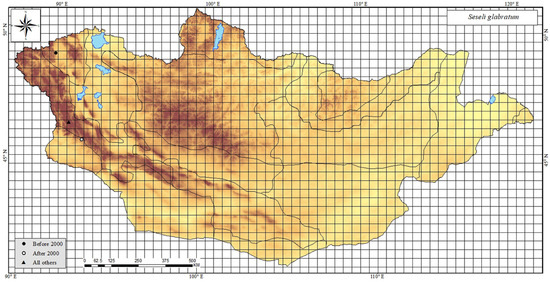

| 60 | Seseli glabratum Willd. | 3 | 8 | EN B2a | - | 6+, 7 | |

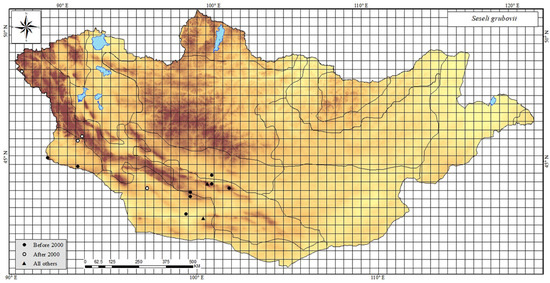

| 61 | Seseli grubovii V.M.Vinogr and Sanchir. (SE) | 18 | 233,295 | 68 | LC | - | 7, 13–15 |

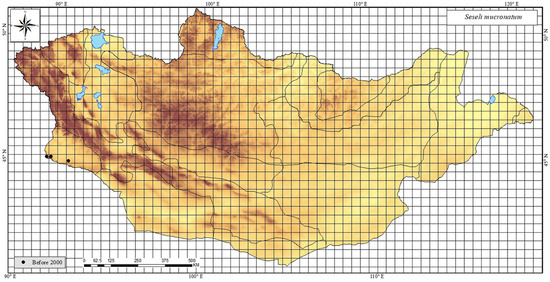

| 62 | Seseli mucronatum (Schrenk) Pimenov and Sdobnina | 6 | 453 | 24 | EN B1a+B2a | - | 14 |

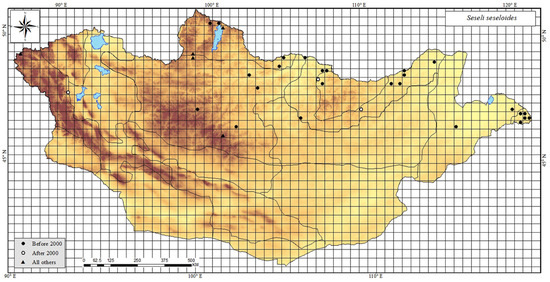

| 63 | Seseli seseloides (Fisch and C.A.Mey.) M.Hiroe. | 39 | 764,906 | 144 | LC | - | 1–5, 7, 9 |

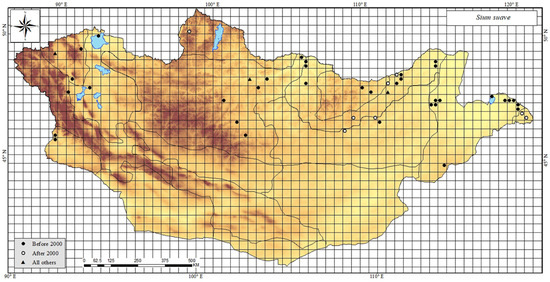

| 64 | Sium suave Walter. | 60 | 987,532 | 220 | LC | - | 1–10, 14 |

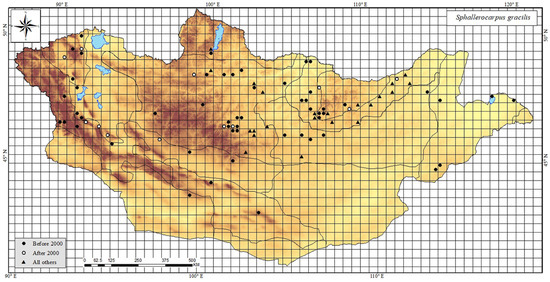

| 65 | Sphallerocarpus gracilis Koso-Pol. | 160 | 1,108,433 | 436 | LC | - | 1–4, 6–11, 13 |

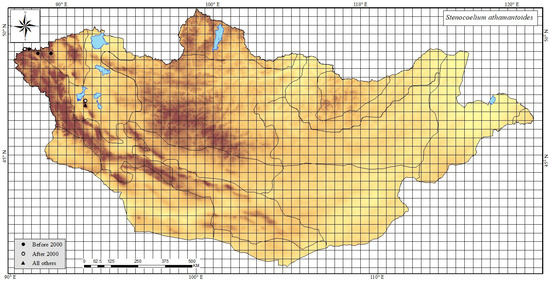

| 66 | Stenocoelium athamantoides Ledeb. | 8 | 13,316 | 28 | VU B1a+B2a | VU [14] | 6, 7 |

Note: Phytogeographical regions: 1—Khuvsgul (Khu), 2—Khentii (Khe), 3—Khangai (Kha), 4—Mongolian Dauria (MD), 5—Foothills of Great Khingan (FGKh), 6—Khovd (Kho), 7—Mongolian Altai (MA), 8—Middle Khalkh (MKh), 9—Eastern Mongolia (EM), 10—Depression of Great Lakes (DGL), 11—Valley of Lakes (VL), 12—Eastern Gobi (EG), 13—Gobi Altai (GA), 14—Dzungarian Gobi (DzG), 15—Trans-Altai Gobi (TAG), 16—Alashan Gobi (AG). IUCN categories: Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), Vulnerable (VU), Near Threatened (NT), and Least Consern (LC). Subendemic areas (SE). The new locations for each region are indicated via plus symbols.

Appendix B. The Wild Photos of Apiaceae in Mongolia

Figure A1.

Some species of Apiaceae in Mongolia. (A) Aegopodium alpestre. (B) Angelica dahurica. (C) Angelica sylvestris. (D) Anthriscus sylvestris. (E) Archangelica decurrens. (F) Bupleurum bicaule. (G) Bupleurum multinerve. (H) Bupleurum scorzonerifolium. (I) Bupleurum sibiricum. (J) Carum buriaticum. (K) Carum carvi. (L) Cenolophium denudatum. (M) Cicuta virosa. (N) Cnidium dahuricum. (O) Cnidium monnieri. (P) Conioselinum longifolium. Photos: (A,C,E–N,P by M.Urgamal), (B,D by B.Oyuntsetseg) and (O by Ch.Javzandolgor).

Figure A2.

Some species of Apiaceae in Mongolia. (A) Conioselinum tataricum. (B) Ferula bungeana. (C) Ferula dshaudshamyr. (D) Ferula ferulioides. (E) Ferula songarica. (F) Ferulopsis hystrix. (G) Haloselinum falcaria. (H) Hansenia mongholica. (I) Heracleum dissectum. (J) Heracleum sibiricum. (K) Kadenia salina. (L) Kitagawia baicalensis. (M) Kitagawia terebinthacea. (N) Lithosciadium multicaule. (O) Neogaya simplex. (P) Ostericum tenuifolium. Photos: (A,B,G,I–P by M.Urgamal), and (C–F,H by B.Oyuntsetseg).

Figure A3.

Some species of Apiaceae in Mongolia. (A) Paraligusticum discolor. (B) Peucedanum puberulum. (C) Peucedanum vaginatum. (D) Phlojodicarpus sibiricus. (E) Phlojodicarpus villosus. (F) Pleurospermum uralense. (G) Sajanella monstrosa. (H) Saposhnikovia divaricata. (I) Schulzia crinita. (J) Seseli buchtormense. (K) Seseli condensatum. (L) Seseli eriocarpum. (M) Seseli glabratum. (N) Seseli seseloides. (O) Sium suave. (P) Sphallerocarpus gracilis. Photos: (A,L,M by B.Oyuntsetseg), (B–D,F,H–K,N–P by M.Urgamal), (E by Ch.Javzandolgor) and (G by Sh.Baasanmunkh).

Appendix C. The Distribution Maps of Apiaceae Species in Mongolia

Figure A4.

Map of general phytogeographical regions of Mongolia (by Grubov 1982). (1—Khuvsgul, 2—Khentei, 3—Khangai, 4—Mongolian Dauria, 5—Foothills of Great Khyangan, 6—Khovd, 7—Mongolian Altai, 8—Middle Khalkh, 9—East Mongolia, 10—Depression of Great Lakes, 11—Valley of Lakes, 12—East Gobi, 13—Gobi Altai, 14—Dzungarian Gobi, 15—Transaltai, 16—Alashan Gobi).

Figure A5.

Distribution of Aegopodium alpestre in Mongolia.

Figure A6.

Distribution of Angelica czernaevia in Mongolia.

Figure A7.

Distribution of Angelica dahurica in Mongolia.

Figure A8.

Distribution of Angelica saxatilis in Mongolia.

Figure A9.

Distribution of Angelica sylvestris in Mongolia.

Figure A10.

Distribution of Anthriscus sylvestris in Mongolia.

Figure A11.

Distribution of Archangelica decurrens in Mongolia.

Figure A12.

Distribution of Aulacospermum anomalum in Mongolia.

Figure A13.

Distribution of Bupleurum aureum in Mongolia.

Figure A14.

Distribution of Bupleurum bicaule in Mongolia.

Figure A15.

Distribution of Bupleurum densiflorum in Mongolia.

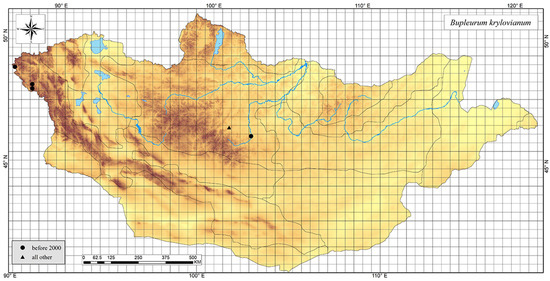

Figure A16.

Distribution of Bupleurum krylovianum in Mongolia.

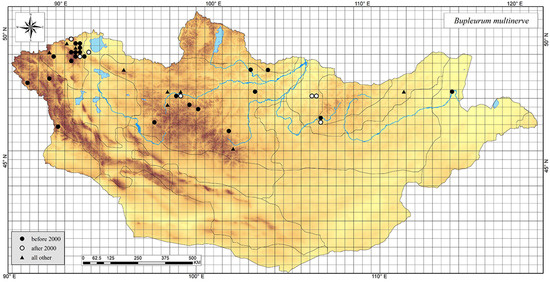

Figure A17.

Distribution of Bupleurum multinerve in Mongolia.

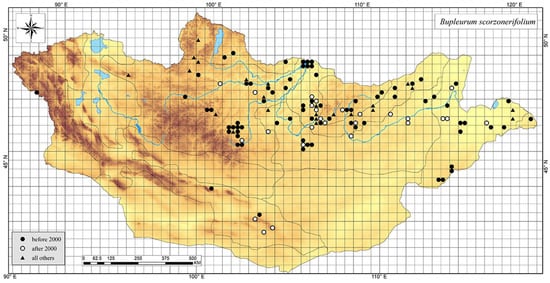

Figure A18.

Distribution of Bupleurum scorzonerifolium in Mongolia.

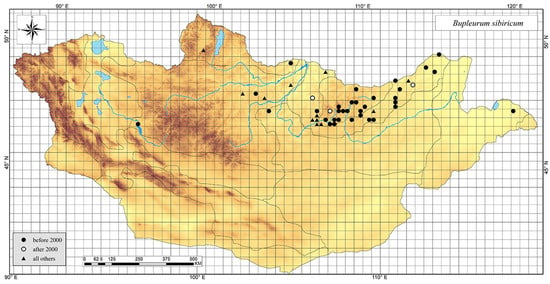

Figure A19.

Distribution of Bupleurum sibiricum in Mongolia.

Figure A20.

Distribution of Carum buriaticum in Mongolia.

Figure A21.

Distribution of Carum carvi in Mongolia.

Figure A22.

Distribution of Cenolophium denudatum in Mongolia.

Figure A23.

Distribution of Cicuta virosa in Mongolia.

Figure A24.

Distribution of Cnidium dahuricum in Mongolia.

Figure A25.

Distribution of Cnidium monnieri in Mongolia.

Figure A26.

Distribution of Conioselinum longifolium in Mongolia.

Figure A27.

Distribution of Conioselinum tataricum in Mongolia.

Figure A28.

Distribution of Elwendia setacea in Mongolia.

Figure A29.

Distribution of Ferula bungeana in Mongolia.

Figure A30.

Distribution of Ferula caspica in Mongolia.

Figure A31.

Distribution of Ferula dissecta in Mongolia.

Figure A32.

Distribution of Ferula dshaudshamyr in Mongolia.

Figure A33.

Distribution of Ferula ferulioides in Mongolia.

Figure A34.

Distribution of Ferula potaninii in Mongolia.

Figure A35.

Distribution of Ferula songarica in Mongolia.

Figure A36.

Distribution of Ferulopsis hystrix in Mongolia.

Figure A37.

Distribution of Haloselinum falcaria in Mongolia.

Figure A38.

Distribution of Hansenia mongholica in Mongolia.

Figure A39.

Distribution of Heracleum dissectum in Mongolia.

Figure A40.

Distribution of Heracleum sibiricum in Mongolia.

Figure A41.

Distribution of Kadenia salina in Mongolia.

Figure A42.

Distribution of Kitagawia baicalensis in Mongolia.

Figure A43.

Distribution of Kitagawia terebinthacea in Mongolia.

Figure A44.

Distribution of Lithosciadium kamelinii in Mongolia.

Figure A45.

Distribution of Lithosciadium multicaule in Mongolia.

Figure A46.

Distribution of Neogaya simplex in Mongolia.

Figure A47.

Distribution of Oenanthe aquatica in Mongolia.

Figure A48.

Distribution of Ostericum tenuifolium in Mongolia.

Figure A49.

Distribution of Paraligusticum discolor in Mongolia.

Figure A50.

Distribution of Peucedanum puberulum in Mongolia.

Figure A51.

Distribution of Peucedanum vaginatum in Mongolia.

Figure A52.

Distribution of Phlojodicarpus sibiricus in Mongolia.

Figure A53.

Distribution of Phlojodicarpus villosus in Mongolia.

Figure A54.

Distribution of Pimpinella thellungiana in Mongolia.

Figure A55.

Distribution of Pleurospermum uralense in Mongolia.

Figure A56.

Distribution of Prangos ledebourii in Mongolia.

Figure A57.

Distribution of Sajanella monstrosa in Mongolia.

Figure A58.

Distribution of Saposhnikovia divaricata in Mongolia.

Figure A59.

Distribution of Schulzia crinita in Mongolia.

Figure A60.

Distribution of Seseli abolinii in Mongolia.

Figure A61.

Distribution of Seseli buchtormense in Mongolia.

Figure A62.

Distribution of Seseli condensatum in Mongolia.

Figure A63.

Distribution of Seseli eriocarpum in Mongolia.

Figure A64.

Distribution of Seseli glabratum in Mongolia.

Figure A65.

Distribution of Seseli grubovii in Mongolia.

Figure A66.

Distribution of Seseli mucronatum in Mongolia.

Figure A67.

Distribution of Seseli seseloides in Mongolia.

Figure A68.

Distribution of Sium suave in Mongolia.

Figure A69.

Distribution of Sphallerocarpus gracilis in Mongolia.

Figure A70.

Distribution of Stenocoelium athamantoides in Mongolia.

References

- Myers, N.; Mittermeler, R.A.; Mittermeler, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Su, X.; Shrestha, N.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sandanov, D.; Wang, Z. Effects of contemporary environment and quaternary climate change on drylands plant diversity differ between growth forms. Ecography 2019, 42, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, J.; Naqinezhad, A.; Talebi, A.; Doostmohammadi, M.; Plutzar, C.; Rumpf, S.B.; Asgarpour, Z.; Schneeweiss, G.M. Hotspots of vascular plant endemism in a global biodiversity hotspot in southwest Asia suffer from significant conservation gaps. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 237, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erst, A.S.; Baasanmunkh, S.; Tsegmed, Z.; Oyundelger, K.; Sharples, M.T.; Oyuntsetseg, B.; Krivenko, D.A.; Gureyeva, I.I.; Romanets, R.R.; Kuznetsov, A.A.; et al. Hotspot and conservation gap analysis of endemic vascular plants in the Altai Mountain Country based on a new global conservation assessment. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 47, e02647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, A.; Azevedo, J.; Leme, E.; Neves, B.; da Costa, A.F.; Caceres, D.; Zizka, G. Biogeography and conservation status of the Pineapple family (Bromeliaceae). Divers. Distrib. 2020, 26, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baasanmunkh, S.; Oyuntsetseg, B.; Oyundari, C.; Oyundelger, K.; Urgamal, M.; Darikhand, D.; Soninkhishig, N.; Nyambayar, D.; Khaliunaa, K.; Tsegmed, Z.; et al. The vascular plant diversity of Dzungarian Gobi in Western Mongolia, with an annotated checklist. Phytotaxa 2021, 501, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevani, A.H.; Liede-Schumann, S.; Akhani, H. Diversity, distribution, endemism and conservation status of Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) in SW Asia and adjacent countries. Plant Syst. Evol. 2020, 306, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandanov, D.; Dugarova, A.; Brianskaia, E.; Selyutina, I.; Makunina, N.; Dudov, S.; Chepinoga, V.; Wang, Z. Diversity and distribution of Oxytropis DC. (Fabaceae) species in Asian Russia. Biodivers. Data J. 2022, 10, e78666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Species richness, endemism, and conservation of wild Rhododendron in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 41, e02375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khapugin, A.A.; Kuzmin, I.V.; Silaeva, T.B. Anthropogenic drivers leading to regional extinction of threatened plants: Insights from regional Red Data Books of Russia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 2765–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baasanmunkh, S.; Urgamal, M.; Oyuntsetseg, B.; Sukhorukov, A.P.; Tsegmed, Z.; Son, D.C.; Erst, A.; Oyundelger, K.; Kechaykin, A.A.; Norris, J.; et al. Flora of Mongolia: Annotated checklist of native vascular plants. PhytoKeys 2022, 192, 63–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyambayar, D.; Oyuntsetseg, B.; Tungalag, R. Mongolian Red List and Conservation Action Plans of Plants; Admon Printing: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2011; p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Oyuntsetseg, B.; Baasanmunkh, S.; Nyambayar, D.; Batkhuu, N.O.; Lee Ch, C.K.S.; Chung, G.Y.; Choi, H.J. The Conservation Status of 100 Rare Plants in Mongolia; Korea National Arboretum Pochein: Pocheon, Republic of Korea, 2018; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Urgamal, M.; Oyuntsetseg, B.; Tungalag, R.; Gundegmaa, V.; Oyundari, C.; Tserendulam, C.; Munkh-Erdene, T.; Solongo, S. Regional Red List Series, 2nd ed.; Mongolica: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2019; Volume 11, p. 230. [Google Scholar]

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet. Available online: www.plantsoftheworldonline.org (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Menglan, S.; Fading, P.; Zehui, P.; Watson, M.F.; Cannon, J.F.M.; Holmes-Smith, I.; Kljuykov, E.V.; Phillippe, L.R.; Pimenov, M.G. Apiaceae; Science Press: Beijing, China; Missouri Botanical Garden: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2005; Volume 14, pp. 1–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pimenov, M.G. Updated checklist of Chinese Umbelliferae: Nomenclature, synonymy, typification, distribution. Turczaninowia 2017, 20, 106–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, M.; Tojibaev, K.S.; Sennikov, A.N.; Khasanov, F.O.; Beshko, N.Y. Taxonomic and nomenclatural inventory of the Umbelliferae in Central Asia, described on the basis of collections of the National Herbarium of Uzbekistan. Plant Divers. Cent. Asia 2022, 1, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar, A.; Iranshahi, M. Biological activities of essential oils from the genus Ferula (Apiaceae). Asian Biomed. 2010, 4, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, G.M.; Pimenov, M.G.; Reduron, J.-P.; Kljuykov, E.V.; van Wyk, B.-E.; Ostroumova, T.A.; Henwood, M.J.; Tilney, P.M.; Spalik, K.; Watson, M.F.; et al. Apiaceae. In Flowering Plants. Eudicots; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 9–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gunin, P.D.; Vostokova, E.A.; Dorofeyuk, N.I.; Tarasov, P.E.; Black, C.C. Vegetation Dynamics of Mongolia; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 26, p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbig, H. The Vegetation of Mongolia; SPB Academic Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; p. 258. [Google Scholar]

- Grubov, V.I. Conspectus of Flora of People’s Republic of Mongolia. In Moscow, Leningrad: Series of Mongolian Commission of Academy of Sciences of USSR; Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1955; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Urgamal, M. Flora of Mongolia, 1st ed.; Bembi san Printing: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2009; Volume 10 (Apiaceae), 133p, ISBN 978-99929-78-14-7. [Google Scholar]

- Baasanmunkh, S.; Oyuntsetseg, B.; Tsegmed, Z.; Oyundelger, K.; Urgamal, M.; Gantuya, B.; Javzandolgor, C.; Nyambayar, N.; Kosachev, P.; Choi, H.J. Distribution of vascular plants in Mongolia−I Part. Mong. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 20, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baasanmunkh, S.; Oyuntsetseg, B.; Tsegmed, Z.; Urgamal, M.; Oyundelger, K.; Nyambayar, N.; Nyamgerel, N.; Erst, A.; Undruul, A.; Choi, H.J. Distribution of vascular plants in Mongolia–II Part. Mong. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 20, 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List—Categories and Criteria; Version 6.1. July 2006; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 11.

- Manawaduge, C.G.; Yakandawala, D.; Yakandawala, K. Does the IUCN Red-Listing ‘Criteria B’ do justice for smaller aquatic plants? a case study from Sri Lankan Aponogetons. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rønsted, N.; Walsh, S.K.; Clark, M.; Edmonds, M.; Flynn, T.; Heintzman, S.; Loomis, A.; Lorence, D.; Nagendra, U.; Nyberg, B.; et al. Extinction risk of the endemic vascular flora of Kauai, Hawaii, based on IUCN assessments. Conserv. Biol. 2022, 36, e13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baasanmunkh, S.; Oyuntsetseg, B.; Efimov, P.; Tsegmed, Z.; Vandandorj, S.; Oyundelger, K.; Urgamal, M.; Undruul, A.; Khaliunaa, K.; Namuulin, T. Orchids of Mongolia: Taxonomy, species richness and conservation status. Diversity 2021, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kherlenchimeg, N.; Burenbaatar, G.; Baasanmunkh, S.; Tsegmed, Z.; Urgamal, M.; Bau, T.; Han, S.-K.; Oh, S.-Y.; Choi, H.J. Improved understanding of the macrofungal diversity of Mongolia: Species richness, conservation status, and an annotated checklist. Mycobiology 2024, 52, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsukh, Z.; Toume, K.; Javzan, B.; Kazuma, K.; Cai, S.-Q.; Hayashi, S.; Atsumi, T.; Yoshitomi, T.; Uchiyama, N.; Maruyama, T.; et al. Characterization of metabolites in Saposhnikovia divaricata root from Mongolia. J. Nat. Med. 2021, 75, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiers, B. Index Herbariorum: A Global Directory of Public Herbaria and Associated Staff. New York Botanical Garden’s Virtual Herbarium. Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Rilke, S.; Najmi, U.; Schnittler, M. Contributions to “E-Taxonomy”—A Virtual Approach to the Flora of Mongolia (FloraGREIF). Feddes Repert. 2012, 123, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF.org. Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Available online: https://www.gbif.org (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, Version 3.1, 2nd ed.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2012.

- Dauby, G.; Stévart, T.; Droissart, V.; Cosiaux, A.; Deblauwe, V.; Simo-Droissart, M.; Sosef, M.S.M.; Lowry, P.P.; Schatz, G.E.; Gereau, R.E. ConR: An R package to assist large-scale multispecies preliminary conservation assessments using distribution Data. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 11292–11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna, Austria. 2016. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Hsieh, T.C.; Ma, K.H.; Chao, A. INEXT: An R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Ill Numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI ArcGIS Desktop 10.1; ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA, 2012.

- Laffan, S.W.; Lubarsky, E.; Rosauer, D.F. Biodiverse, a tool for the spatial analysis of biological and related diversity. Ecography 2010, 33, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffan, S.W.; Crisp, M.D. Assessing endemism at multiple spatial scales, with an example from the Australian vascular flora. J. Biogeogr. 2003, 30, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).