Abstract

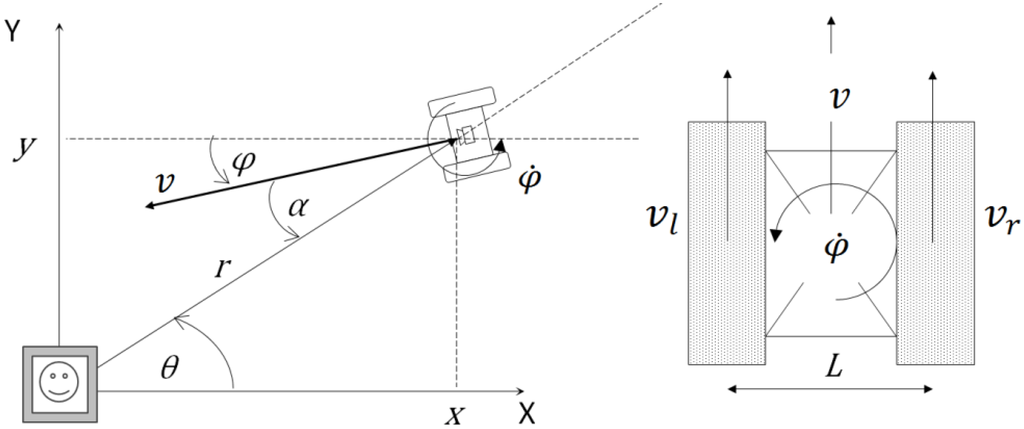

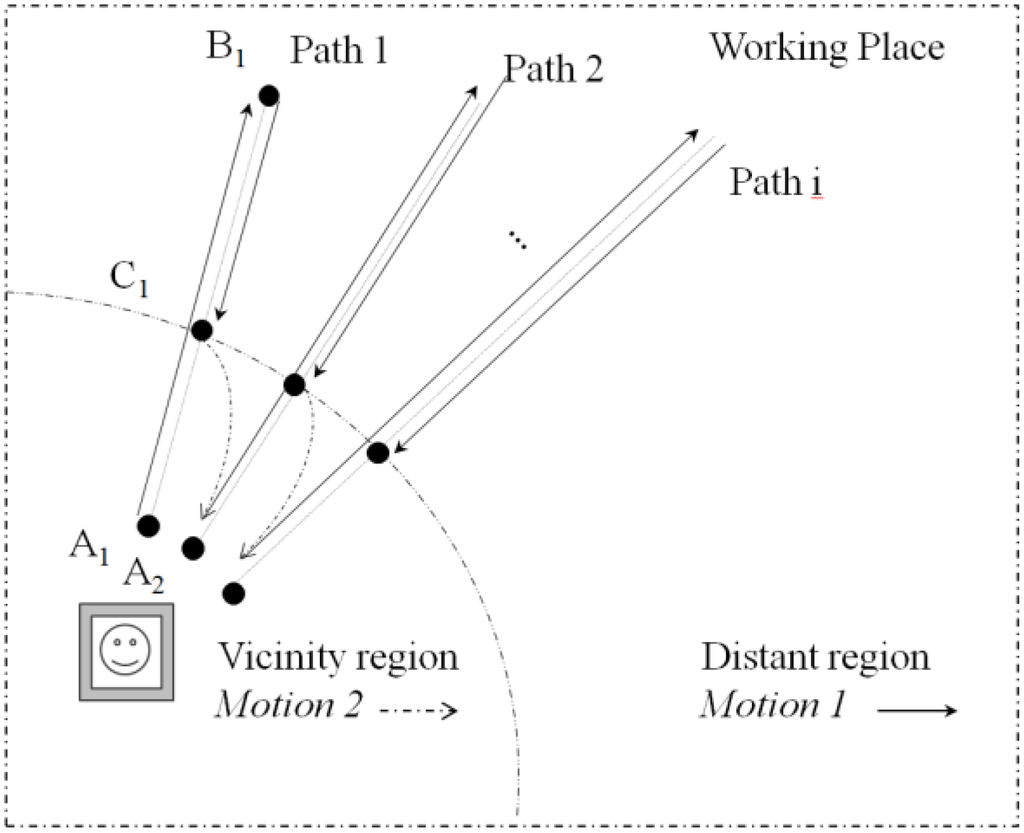

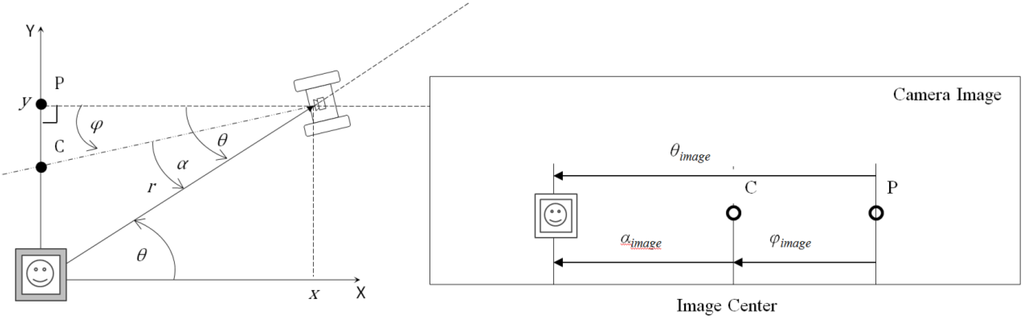

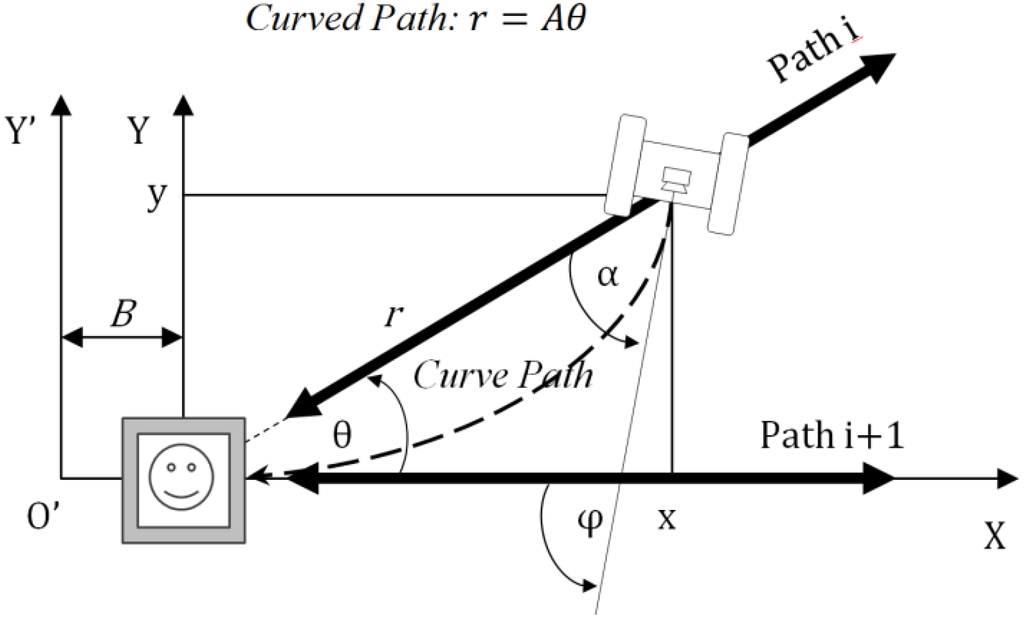

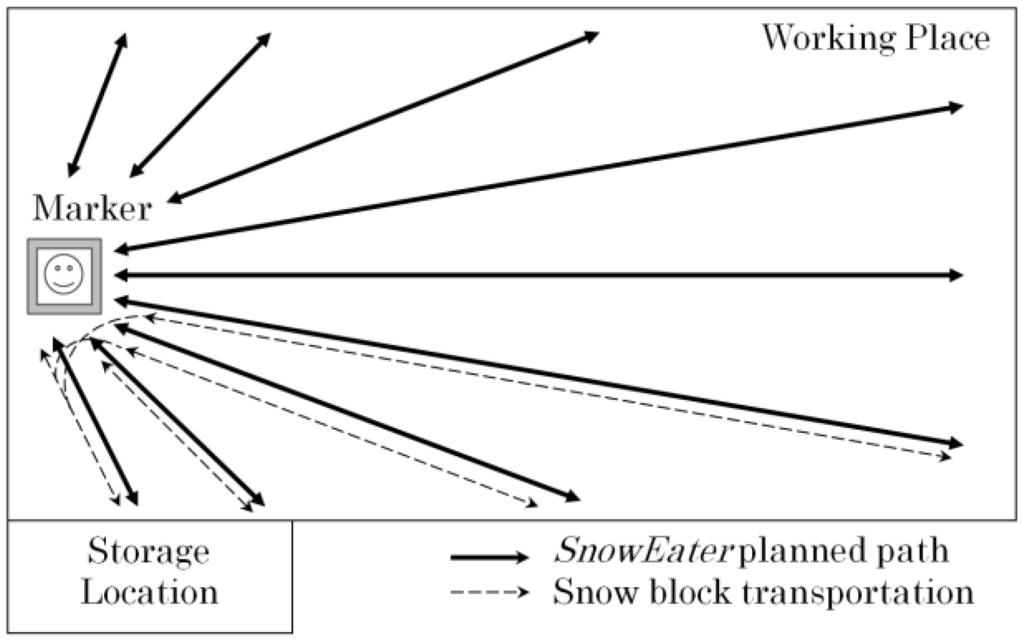

This paper reports on a navigation method for the snow-removal robot called SnowEater. The robot is designed to work autonomously within small areas (around 30 m2 or less) following line segment paths. The line segment paths are laid out so as much snow as possible can be cleared from an area. Navigation is accomplished by using an onboard low-resolution USB camera and a small marker located in the area to be cleared. Low-resolution cameras allow only limited localization and present significant errors. However, these errors can be overcome by using an efficient navigation algorithm to exploit the merits of these cameras. For stable robust autonomous snow removal using this limited information, the most reliable data are selected and the travel paths are controlled. The navigation paths are a set of radially arranged line segments emanating from a marker placed in the environment area to be cleared, in a place where it is not covered by snow. With this method, by using a low-resolution camera (640 × 480 pixels) and a small marker (100 × 100 mm), the robot covered the testing area following line segments. For a reference angle of 4.5° between line paths, the average results are: 4° for motion on hard floor and 4.8° for motion on compacted snow. The main contribution of this study is the design of a path-following control algorithm capable of absorbing the errors generated by a low-cost camera.

1. Introduction

Robot technology is focused on increasing the quality of life by the creation of new machines and methods. This paper reports on the development of a snow-removal robot called SnowEater. The concept for this robot is the creation of a safe, slow, small, light, low-powered and inexpensive autonomous snow-removal machine for home use. In essence, SnowEater can be compared with autonomous vacuum cleaner robots [1], but instead of working inside homes, it is designed to operate on house walkways, and around front doors or garages. A number of attempts to automate commercial snow-blower machines have being made [2,3], but such attempts have been delayed out of concerns over safety.

The basic SnowEater model is derived from the heavy snow-removal robot named Yukitaro [4], which was equipped with a high-resolution laser rangefinder for the navigation system. In contrast to the Yukitaro robot, which weights 400 kg, the SnowEater robot is planned to weigh 50 kg or less. In 2010, a snow-intake system was fitted to SnowEater [5] that enables snow removal using low auger and traveling speeds while following a line path. In 2012, a navigation system based on a low-cost camera was introduced [6]. The control system was designed using linear feedback to ensure paths were followed accurately. However, due to the reduced localization accuracy, the system did not prove to be reliable. Among the many challenges in the realization of autonomous snow-removal robots, is the navigation and localization issue, which currently remains unsolved.

An early work on autonomous motion on snow is presented in [7]; in which four cameras and a scan laser were used for simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM); and long routes in polar environments were successfully traversed. The mobility of several small tracked vehicles moving in natural and deep-snow environments is discussed in [8,9]. The terramechanics theory for motion on snow presented in [10] can be applied to improve the performance of robots moving on snow.

The basic motion models presented in [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] can be used for motion control. In addition, Gonzalez et al. [19] presented a model for off-road conditions. Also, the motion of a tracked mobile robot (TMR) on snow is notably affected by slip disturbance. In order to ensure the performance of path tracking or path following control against disturbances, robust controllers [20,21] and controllers based on advanced sensors [22] exist. However, advanced feedback compensation based on precise motion modeling is not necessary for this application because strict tracking is not required in our snow-removal robot.

One of the goals of this study is to develop a simple controller without the need for precise motion modeling. Another goal is to use a low-cost vision-based navigation system that does not require a large budget or an elaborate setup in the working environment. In contrast to other existing navigation strategies that use advanced sensors, we use only one low-cost USB camera and one marker for motion controlling.

This paper presents an effective method of utilizing a simple directional controller based on a camera-marker combination. In addition, a path-following method to enhance the reliability of navigation is proposed. Although the directional controller itself does not provide asymptotic stability of the path to follow, the simplicity of the system is a significant merit.

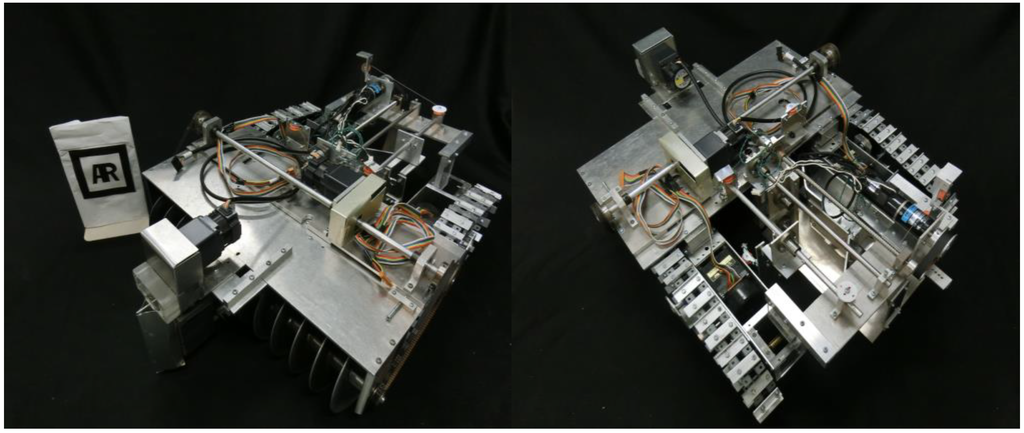

2. Task Overview and Prototype Robots

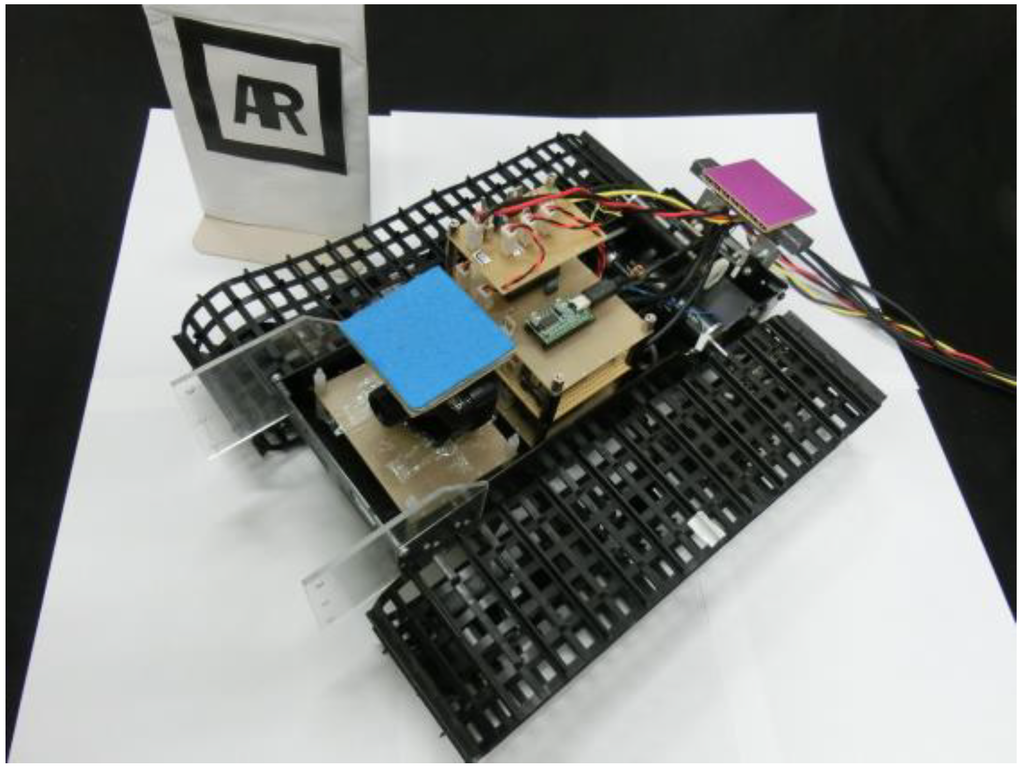

The SnowEater robot prototype was developed in our laboratory. The prototype is a tracked mobile robot (TMR). Its weight currently is 26 kg, and the size is 540 mm × 740 mm × 420 mm. The main body is made of aluminum and has a flat shape for stability on irregular terrain. The intake system consists of steel and aluminum conveying screws that collect and compact snow at a low rotation speed. Two 10 W DC motors are used for the tracks, and two 15 W DC motors are used for the screws.

The front screw collects snow when the robot is moving with slow linear motion. The two internal screws compact the snow into blocks for easy transportation. Once the snow is compacted, the blocks are dropped out from the rear of the robot. In addition, the intake system compacts the snow in front of the robot reducing the influence of the track sinkage. Since the robot requires a linear motion to collect snow [5], the path to follow consists of line segments that cover the working area. In our plan, another robot carries the snow blocks to a storage location. Figure 1 shows the prototype SnowEater robot, and Figure 2 shows the line arrangement of the path-following method.

Figure 1.

SnowEater robot prototype.

Figure 2.

Line paths that cover the snow-removal area.

4. Experimental Results

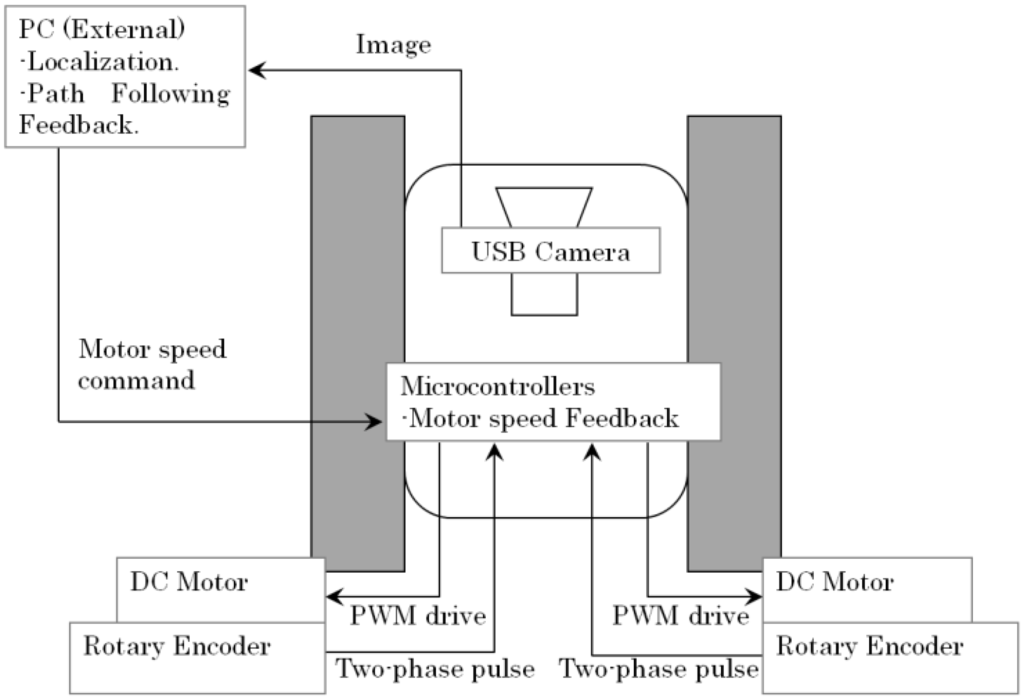

Experimental verification was carried out using the small version of the SnowEater robot. The track motors of the small version are Maxon RE25 20 W motors. Each track speed is PI feedback controlled by using 500 ppr rotary encoders (Copal, RE30E) with 10 ms of sampling period. The control signals are sent through a USB-serial connection between an external PC and the robot microcontrollers (dsPIC30F4012). The PC has an Intel Celeron CPU B830 (1.8 GHz) processor with 4 GB of RAM. The interface is made via Microsoft Visual Studio 2010. Figure 13 shows the system diagram. The track response to different robot angular velocity commands () can be seen in Appendix B.

Figure 13.

Control system diagram for the SnowEater robot.

4.1. Motion 2

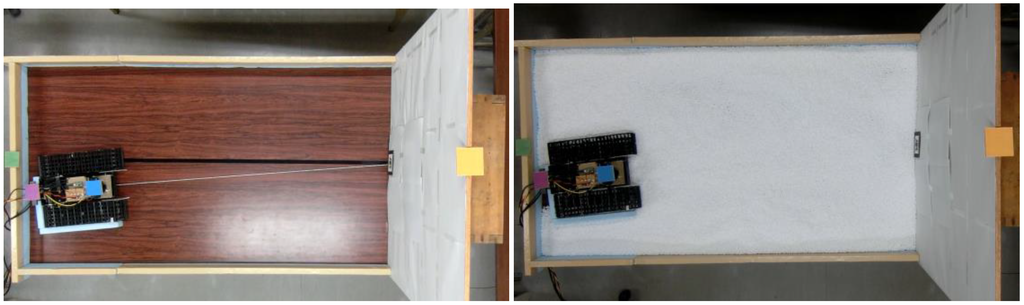

In this experiment, Motion 2 navigation is tested. The control objective is to move the robot to the target line. The experiment is carried out using two different conditions: (1) a hard floor, and (2) a slippery floor of 6 mm polystyrene beads. Figure 14 shows the experimental setups.

Figure 14.

Motion 2 experimental setup on a hard floor, and on a slippery floor of polystyrene beads.

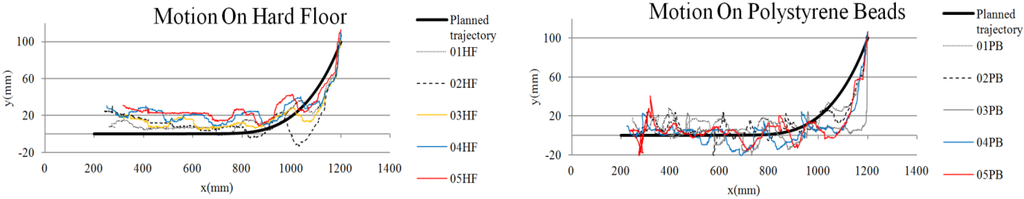

The robot position results are obtained using a high-resolution camera mounted on the top of the robot. The robot and marker locations are generated by processing the captured image. The initial position was xo = 1200 mm, yo = 100 mm. Figure 15 and Figure 16 show the experimental results.

Figure 15.

Robot position throughout the experiment.

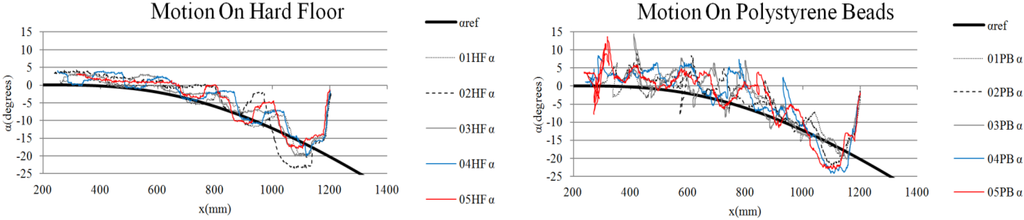

Figure 16.

experimental results when Motion 2 is executed.

Figure 15 shows a comparison of the Motion 2 experiment on a hard floor and on polystyrene beads repeated five times.

As Figure 16 shows, direction control for the angle is accomplished.

Because the feedback does not provide asymptotic stability of the path to follow, deviations occur in each experiment. If the final position is not accurate, tracking of the path generated by Motion 1 cannot be achieved. If the final error is outside the allowable range, a new curve using the Motion 2 control needs to be generated again. Due to the marker proximity, tracking of the new path is more accurate.

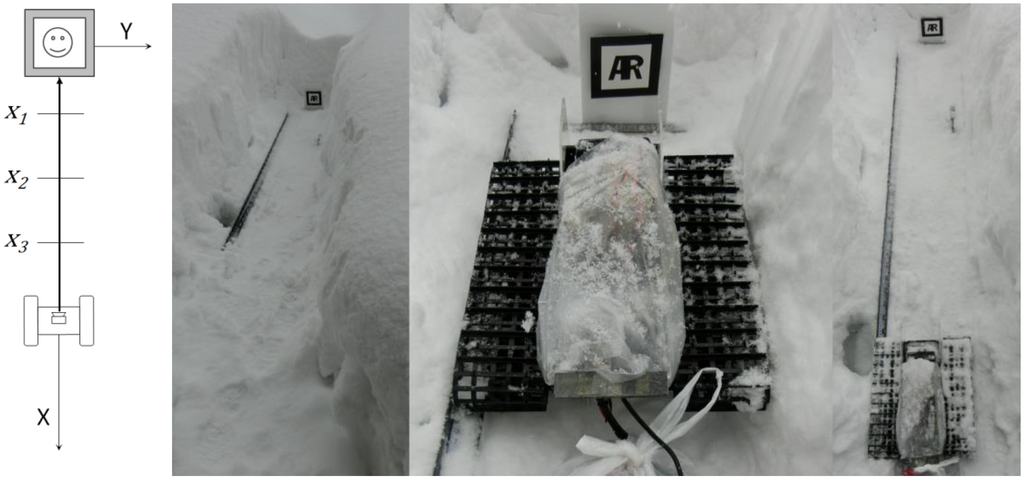

4.2. Motion 1 in Outdoor Conditions

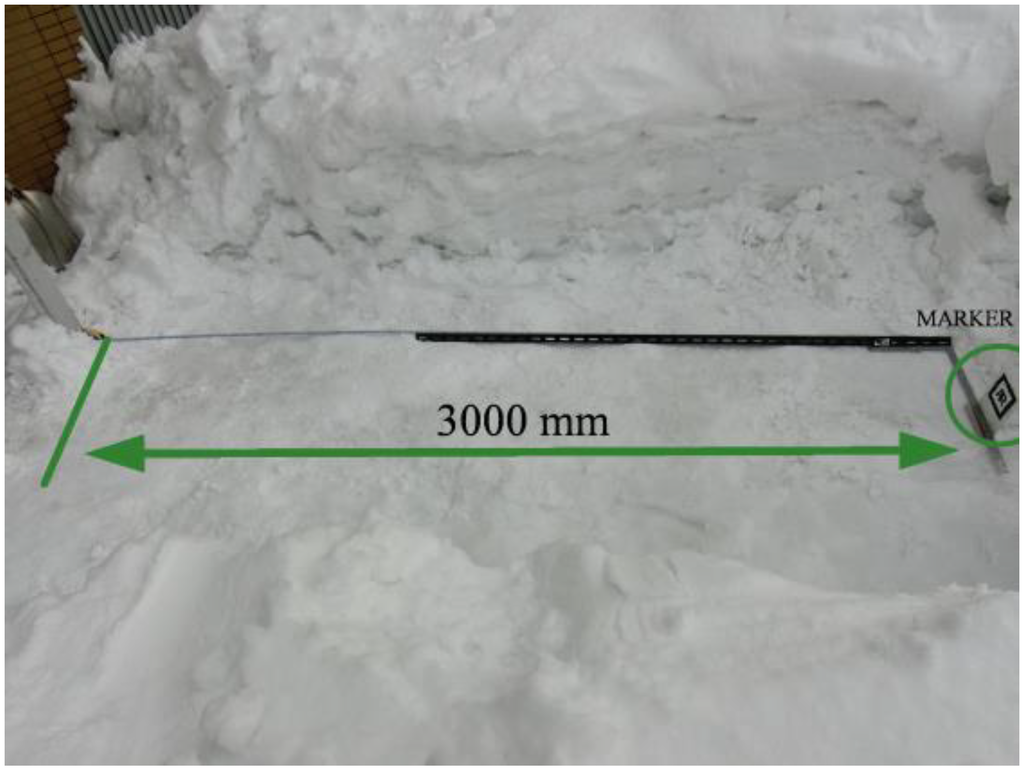

To confirm the applicability in snow environments of this path-following strategy, outdoor experiments were carried out. These experiments were conducted at different times of the day under different lighting conditions. Figure 17 shows the setup of the test area.

Figure 17.

Test area setup.

The test area measured 3000 mm × 1500 mm. The snow on the ground was lightly compacted, the terrain was irregular, and conditions were slippery. For the first experiment, the snow temperature was −1.0 °C and the air temperature is −2.4 °C with good lighting conditions. Figure 18 shows the experimental results for Motion 1 in outdoor conditions. In both experiments, the robot was oriented toward the marker and the path to follow was 3000 mm long. The color lines in the figures highlight the path followed.

Figure 18.

Motion 1 experimental results on snow in outdoor conditions.

As can be seen in Figure 18, the robot follows a straight-line path while using Motion 1.

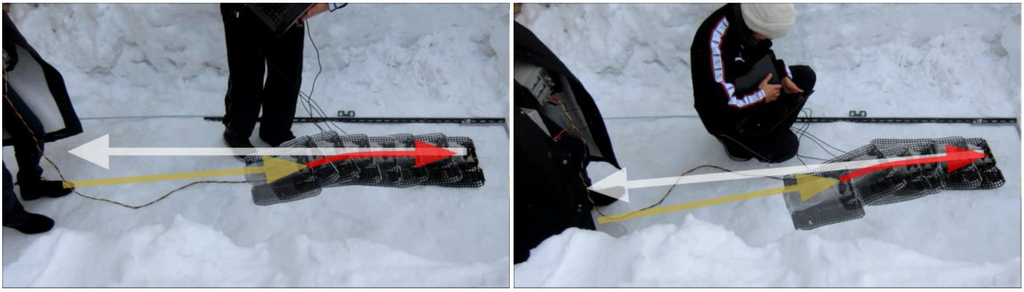

4.3. Motion 2 in Outdoor Conditions

Figure 19 shows the results for the Motion 2 experiment conducted under the same experimental conditions as for the Motion 1 experiment. The color lines highlight the previous path (brown), the path followed (red), and the next path (white).

In the left-hand photograph in Figure 19, the next path is in front of the marker. In the right-hand photograph, the next path has an angle with respect to the marker.

Figure 19.

Motion 2 on snow.

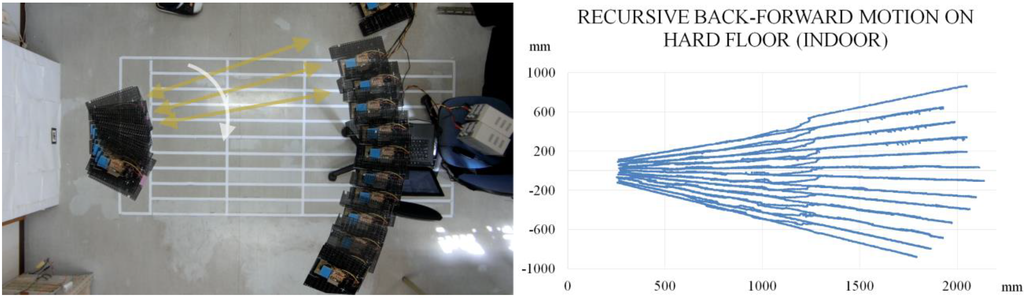

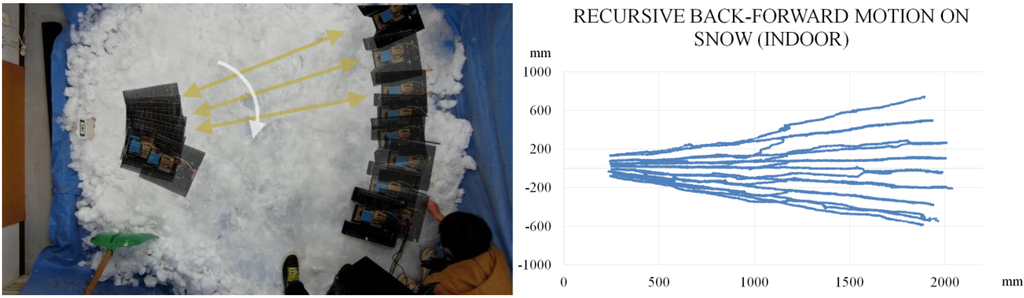

4.4. Recursive Back-Forward Motion

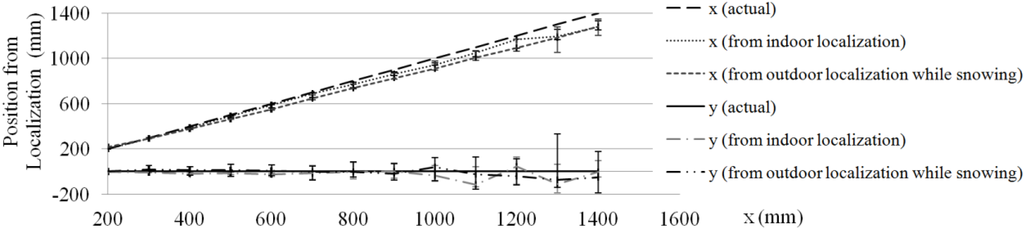

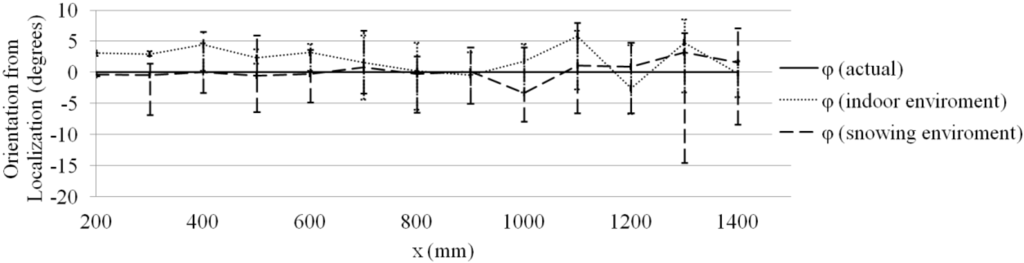

Figure 20 shows the results for the recursive back-forward motion in indoor conditions on a hard floor and on snow. The Motion 2 region is 1200 mm. The test travelled distance is 2000 mm.

Figure 20.

Recursive back-forward motion experimental results in indoor conditions.

Table 1.

Recursive back-forward motion experimental results in indoor conditions.

| On Hard Floor | On Snow | |

|---|---|---|

| Reference angle between paths | 4.5° | 4.5° |

| Mean angle between paths | 4.0° | 4.8° |

| Max. angle between paths | 4.6 ° | 6.9 ° |

| Min. angle between paths | 3 ° | 1.6 ° |

| Angle between paths deviation | 0.49° | 1.54° |

The robot covered the testing area using the recursive back-forward motion. For a reference angle of 4.5° between line paths, the average results are: 4° for motion on hard floor and 4.8° for motion on compacted snow. The number of paths in the experiment on snow is different because the test area on snow is smaller than the test area on hard floor. Although the motion performance on snow is reduced (compared to the motion on a hard floor), the robot returned to the marker and covered the area. Table 1 shows the results of Figure 20.

In snow removal and cleaning applications, full area coverage rather than strict path-following is required. Therefore, this method can be applied for such tasks.

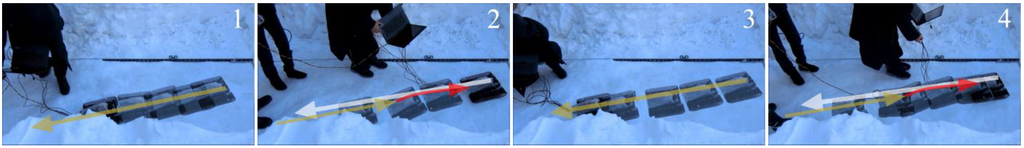

Figure 21 shows the recursive back-forward motion experiment on snow in outdoor conditions. The snow temperature was −1.0 °C and the air temperature was −1.3 °C.

Figure 21.

Recursive back-forward motion experimental results in outdoor conditions.

Figure 21 results confirm the applicability of the method under outdoor snow conditions. Due to poor lighting, the longest distance traveled was 1500 mm. For longer routes, a bigger marker is required and to improve the library performance in poor lighting conditions, the luminous markers shown in [31] can be used.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented a new approach for a snow-removal robot utilizing a path-following strategy based on a low-cost camera. Using only a simple direction controller, an area with radially arranged line segments was swept. The advantages of the proposed controller are its simplicity and reliability.

The required localization values, as measured by the camera, are the position and orientation of the robot. These values are measured in the marker vicinity in a stationary condition. During motion or in the marker distant region, only the position of the marker blob in the captured image is used.

With 100 mm × 100 mm square monochromatic marker, a low-cost USB camera (640 × 480 pixels), and the ARToolKit library, the robot followed the radially arranged line paths. For a reference angle of 4.5° between line paths, the average results are: 4° for motion on hard floor and 4.8° for motion on compacted snow. With good lighting conditions, 3000 mm long paths were traveled. We believe with this method our intended goal area can be covered.

Although the asymptotic stability of the path is not provided, our method presents a simple and convenient solution for SnowEater motion in small areas. The results showed that the robot can cover all the area using just one landmark. Finally, because the algorithm grants area coverage, it can be applied not only to snow-removal but also to other tasks such as cleaning.

In the future, the method will be evaluated by using the SnowEater prototype in outdoor snow environments. Also, the use of natural passive markers (e.g., houses and trees) will be considered.

Appendix A

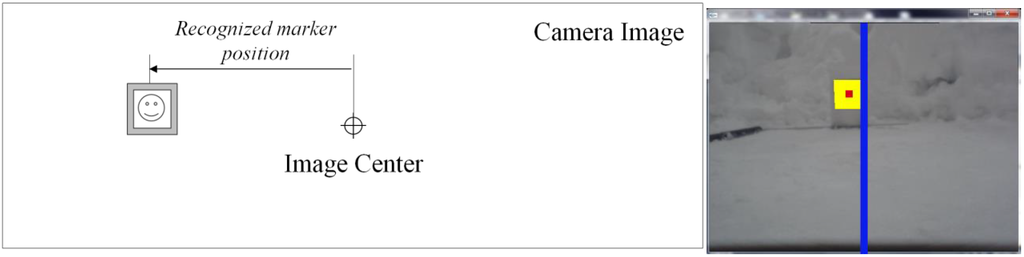

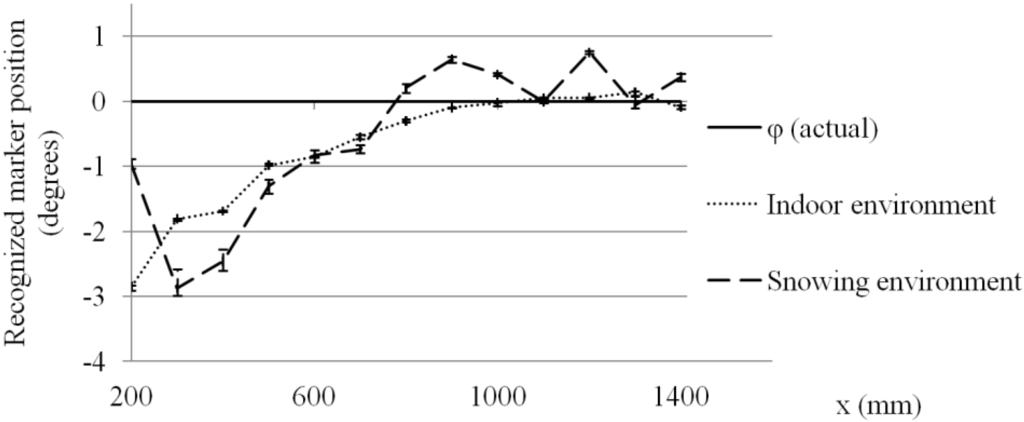

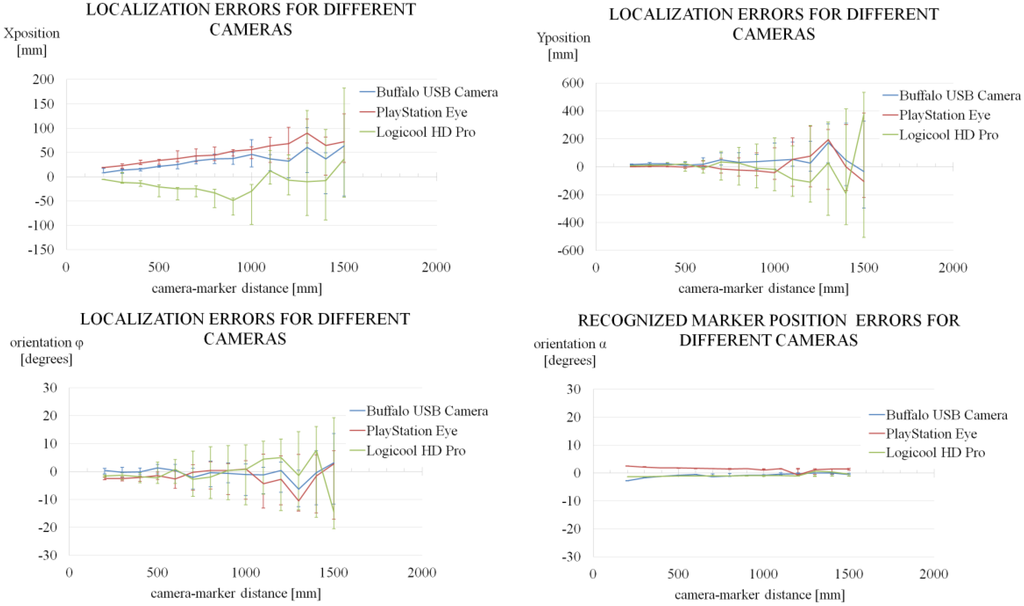

The camera, marker size and the pattern (inside the marker) selection was done after the following indoor experiments. In these experiments, three different parameters were considered: the camera, the marker size and the pattern inside the marker.

In the first experiment, three different cameras (Buffalo USB camera, SONY PlayStation Eye and Logicool HD Pro webcam) were tested. The cameras were set to 30 fps and 640 × 480 pixels. The marker size was 100 × 100 mm and the pattern inside the marker was the same. Figure A1 shows the results.

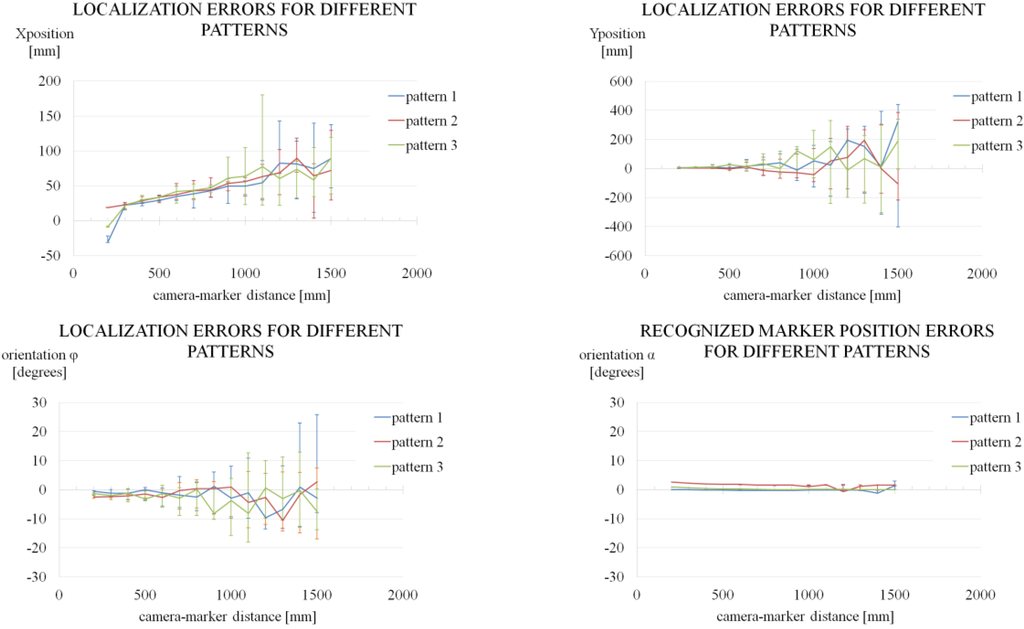

In the second experiment, the pattern inside the marker was changed. The camera was Sony PlayStation Eye set to 30 fps and 640 × 480 pixels. The size for each marker was 100 × 100 mm. Figure A2 shows these results.

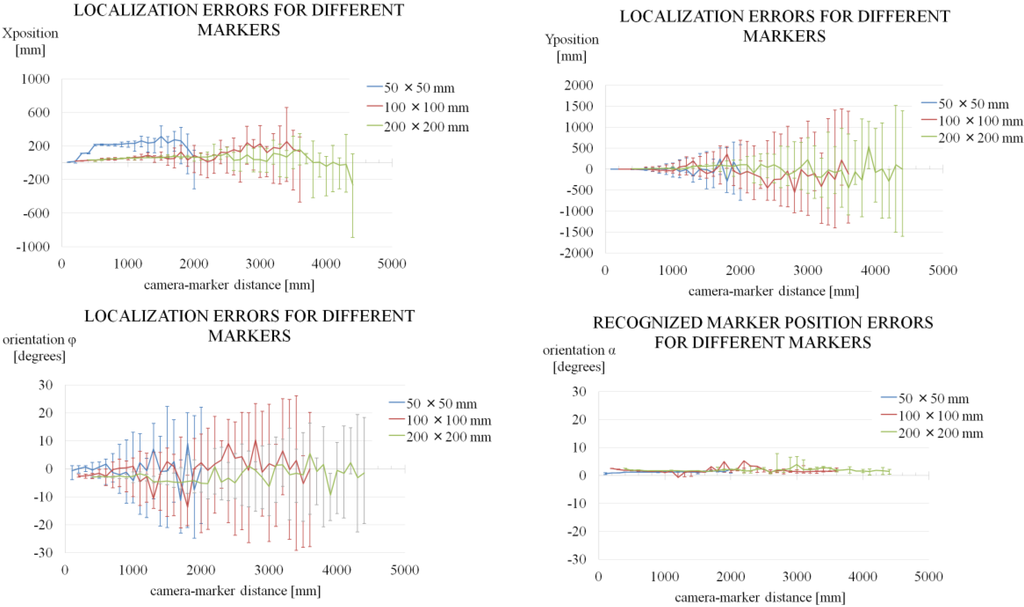

In the third experiment, the marker size was changed. The camera was Sony PlayStation Eye set to 30 fps and 640 × 480 pixels. The pattern inside each marker was the same. Figure A3 shows these results.

Figure A1.

Localization and recognized marker position errors for different cameras.

Figure A2.

Localization and recognized marker position errors for different patterns.

Figure A3.

Localization and recognized marker position errors for different marker size.

These are the conclusions from these experiments: The camera hardware has not direct influence in the localization results when set to the same resolution and frame rate. The pattern inside the marker has not relevant influence in the localization results. The marker size is the most relevant factor in the localization accuracy. A larger marker will have a large accurate region but this region is in the vicinity of the marker and proportional to the marker size.

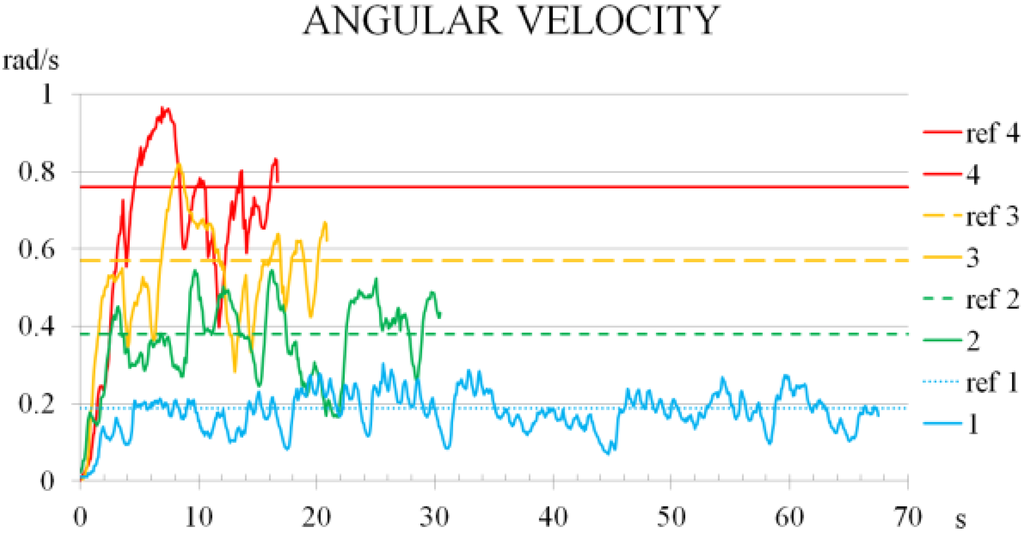

Appendix B

An experiment to check the track response to different robot angular velocity commands () was done. The floor was hard and dry. In the test, the robot rotated 2 revolutions (2π rad) for a given angular velocity, thus the test duration was shorter for higher rotation ratio. Figure B1 shows these results.

Figure B1.

Track response to different angular velocity commands.

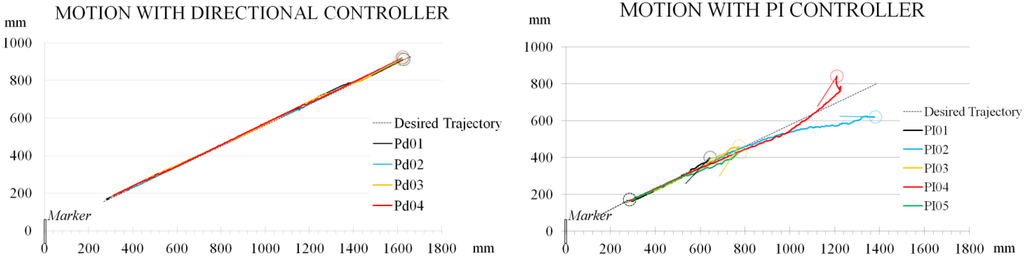

Appendix C

An experiment to compare our controller (using the recognized marker position signal) and the conventional path following linear feedback [12] with PI controller (using position/orientation signals from ARToolKit) was done. The control equation of the latter is:

where and represents the relative angle and distance from the target trajectory, respectively, and , are constant feedback gains.

The marker size was 100 × 100 mm and the camera in use is Sony PlayStation Eye. The floor was hard and dry. Figure C1 show the results.

Figure C1.

Direction controller (recognized marker position) vs. PI controller (inaccurate localization signals).

These results show the behavior of both controllers. In the PI01, PI03 and PI05 experiments the robot lost the marker from the camera vision range; hence the robot stopped.

The PI controller works only in the marker vicinity where the localization signals are accurate. Once the camera-marker distance increases the controller does not work properly due to the poor accuracy of the data. In contrast the direction controller remains stable even if the camera-marker distance increases.

Author Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Irobot home page. Available online: http://www.irobot.com/For-the-Home/Vacuum-Cleaning/Roomba (accessed on 14 November 2014).

- Sato, T.; Makino, T.; Naruse, K.; Yokoi, H.; Kakazu, Y. Development of the Autonomous Snowplow. In Proceedings of ANNIE 2003, St. Louis, MI, USA, 2–5 November 2003; pp. 877–882.

- Suzuki, S.; Kumagami, H.; Haniu, H.; Miyakoshi, K.; Tsunemoto, H. Experimental study on an Autonomous Snowplow with a Vision Sensor. Bull. Univ. Electro-Commun. 2003, 15, 2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Industrial Research Institute of Niigata Prefecture. “Yuki-Taro” the autonomous snowplow; Report on the Prototype Robot Exhibition EXPO 2005 AICHI; Industrial Research Institute of Niigata Prefecture: Niigata, Japan, March 2006; ( In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Mitobe, K.; Rivas, E.; Hasegawa, K.; Kasamatsu, R.; Nakajima, S.; Ono, H. Development of the Snow Dragging Mechanism for an Autonomous Snow Eater Robot. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration, Sendai, Japan, 22–23 December 2010; pp. 73–77.

- Rivas, E.; Mitobe, K. Development of a Navigation System for the SnowEater Robot. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration, Fukuoka, Japan, 16–18 December 2012; pp. 378–383.

- Moorehead, S.; Simmons, R.; Apostolopoulos, D.; Whittaker, W. Autonomous Navigation Field Results of a Planetary Analog Robot in America. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence, Robotics and Automation in Space, Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 1–3 June 1999.

- Lever, J.; Denton, D.; Phetteplace, G.; Wood, S.; Shoop, S. Mobility of a lightweight tracked robot over deep snow. J. Terramech. 2006, 43, 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, J.; shoop, S.; Bernhard, R. Design of lightweight robots for over-snow mobility. J. Terramech. 2009, 46, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.Y. Theory of Ground Vehicles, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Chapter 6, Steering of tracked vehicles; pp. 419–449. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, G.; Jenkin, M. Fundamental Problems. In Computational Principles of Mobile Robotics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, G.; Jenkin, M. Mobile Robot Hardware. In Computational Principles of Mobile Robotics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, G.; Jenkin, M. Visual Sensors and Algorithms. In Computational Principles of Mobile Robotics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, G.; Jenkin, M. Pose Maintenance and Localization. In Computational Principles of Mobile Robotics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Canudas, C.; Siciliano, B.; Bastin, G. Modelling and structural properties. In Theory of Robot Control, 1st ed.; Springer: London, 1997; p. 278. [Google Scholar]

- Canudas, C.; Siciliano, B.; Bastin, G. Nonlinear feedback control. In Theory of Robot Control, 1st ed.; Springer: London, 1997; pp. 331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, P.; Samson, C. Motion control of wheeled mobile robots. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Siciliano, K., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 799–826. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, G.; Chung, W. Wheeled Robots. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Siciliano, K., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, R.; Rodriguez, F.; Guzman, J. Modelling Tracked Robots in Planar Off-Road Conditions. In Autonomous Tracked Robots in Planar Off-Road Conditions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Normey-Rico, J.; Alcala, I.; Gomez-Ortega, J.; Camacho, E. Mobile robot path tracking using robust PID controller. Control Eng. Pract. 2001, 9, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.; Nunes, U. Path-following Control of Mobile Robots in Presence of Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2005, 21, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C.B.; Wang, D.W. GPS-Based Path Following Control for a Car-Like Wheeled Mobile Robot With Skidding and Slipping. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2008, 16, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARToolKit home page. Available online: http://www.hitl.washington.edu/artoolkit/ (accessed on 14 November 2014).

- Kato, H.; Bullinghurst, M. Marker tracking and HMD calibration for a video-based augmented reality conferencing system. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE and ACM International Workshop, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–21 October1999; pp. 85–94.

- Gonzalez, R.; Rodriguez, F.; Guzman, J.; Pradalier, C.; Siegward, S. Control of off-road mobile robots using visual odometry and slip compensation. Adv. Robot. 2013, 27, 893–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkhani, M.; Forsati, R.; Shahri, A.M.; Moayedikia, A. A novel efficient algorithm for mobile robot localization. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, S. An algorithm for robot motion detection by means of a stereoscopic vision system. Adv. Robot. 2013, 27, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Shiozawa, H.; Fukao, T.; Yokokohji, Y. Dense 3D Reconstruction Using a Rotational Stereo Camera and a Correspondence with Epipolar Transfer. J. Robot. Soc. Jpn. 2013, 31, 1019–1027. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. Visual Servoing Trajectory Tracking of Nonholonomic Mobile Robots Without Direct Position Measurement. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2014, 30, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiozawa, H.; Yoshida, T.; Fukao, T.; Yokokohji, Y. 3D Reconstruction using Airbone Velodyne Laser Scanner. J. Robot. Soc. Jpn. 2013, 31, 992–1000. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, M.; Shimonomura, K. Marker Based Camera Pose Estimation for Underwater Robots. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration, Fukuoka, Japan, 16–18 December 2012; pp. 629–634.

- Haddad, W.M.; Chellaboina, V. Stability Theory for Nonlinear Dynamical Systems. In Nonlinear Dynamical Systems and Control; Princenton University Press: New Jersey, USA, 2008; pp. 135–182. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).