Abstract

Highly pathogenic coronaviruses have caused significant outbreaks in humans and animals, posing a serious threat to public health. The rapid global spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has resulted in millions of infections and deaths. However, the mechanisms through which coronaviruses evade a host’s antiviral immune system are not well understood. Liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) is a recently discovered mechanism that can selectively isolate cellular components to regulate biological processes, including host antiviral innate immune signal transduction pathways. This review focuses on the mechanism of coronavirus-induced LLPS and strategies for utilizing LLPS to evade the host antiviral innate immune response, along with potential antiviral therapeutic drugs and methods. It aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding and novel insights for researchers studying LLPS induced by pandemic viruses.

1. Introduction

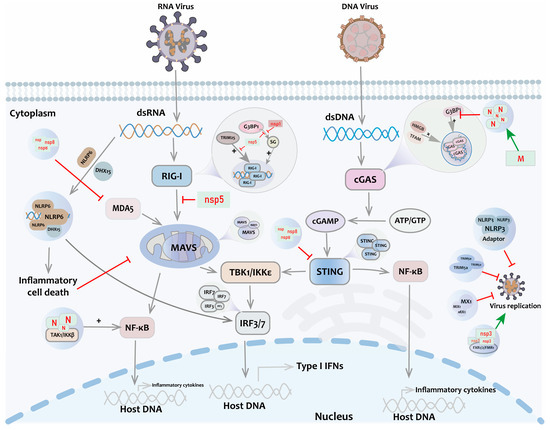

Cellular biological processes with complex regulatory mechanisms are often localized to specific regions, encompassing various membrane-bound organelles and non-membrane-bound organelles. These distinct regions play crucial roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis and facilitating various biological activities by segregating and compartmentalizing the cellular components [1]. Such regulation of cellular processes is fundamental to the understanding of cellular biology and has far-reaching implications in various fields of study. Unlike membranous organelles, membraneless organelles (MLOs) rely on liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) to assemble proteins and nucleic acids [2]. Examples of MLOs include Cajal and promyelocytic leukemia (PML) bodies in the nucleus and processing bodies (PBs) and stress granules (SGs) in the cytoplasm [3]. LLPS can selectively polymerize or segregate specific cytoplasmic components and plays an important role in regulating biological processes. The host’s natural immune system encodes several pathogen pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [4]. These receptors recognize the pathogenic molecular pattern of the pathogen, initiating the production of interferons and cytokines with antiviral and immunomodulatory functions through a complex intracellular signaling process. They serve as the first barrier against the invasion of pathogenic microorganisms [5].

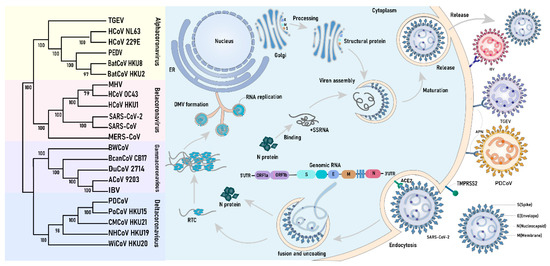

Coronaviruses (CoVs) form a highly diverse pathogenic virus family inducing human and animal diseases. Low-pathogenic human CoVs (HCoVs), such as HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1, cause the common cold. High-pathogenic HCoVs, such as SARS-CoV-1, MERV-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, can develop into severe, life-threatening respiratory pathologies and lung injuries [6]. In the past, they have caused major widespread outbreaks. Moreover, CoVs that infect livestock and poultry species are an important veterinary and economic concern. Recent studies have shown that CoV infection can modulate LLPS in host cells, influencing viral replication and immune evasion mechanisms [7,8]. Hence, this review focuses on the most recent advancements in basic and applied research in this field, with the goal of enhancing our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of coronaviruses and facilitating the development of effective antiviral strategies.

7. Summary and Outlook

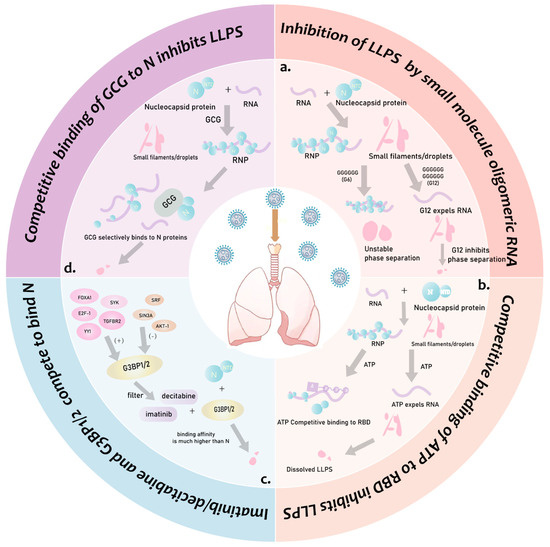

CoVs are the most important human and animal pathogens, and they seriously threaten public health safety. However, there are currently no specific drugs available for the treatment of CoVs. CoVs exhibit a high degree of complexity in their pathogenesis, and a large number of unanswered questions remain in current scientific research. Given the long lead time, high cost, and multiple scientific and technical challenges in the development of a single antiviral drug, the vaccination strategy remains the current optimal choice for the prevention and control of coronavirus infections due to its relatively mature development process and proven safety record. Despite this, drug therapy plays a crucial role among infected persons. The medication provides an individualized treatment plan that is tailored to the patient’s specific condition, physical differences, and age profile, which significantly improves the effectiveness of the treatment. The effectiveness of the vaccine may be challenging given the mutating nature of CoVs. However, drug therapy has demonstrated the potential to cope with different viral variants by flexibly adjusting the drug type and dose. Furthermore, the proposed therapeutic strategy based on the liquid–liquid phase separation mechanism of CoVs may have a broad spectrum of applicability, not only to the current virus but also to other viruses that possess the liquid–liquid phase separation mechanism. The proposed therapeutic strategy provides a new perspective for drug discovery and development, which is important for the future development of antiviral drugs.

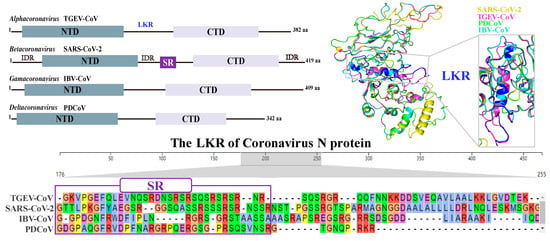

LLPS is still a new field for exploring viral replication and participation in the regulation of host biological processes. In recent years, studies have proven that the process of SARS-CoV-2-induced LLPS involves the interaction of N proteins and their Nsps with RNA, as well as the regulation of temperature, pH, salt concentration, and ATP. On the one hand, CoV-induced LLPS is beneficial to the aggregation of viral replication complexes, which can improve the efficiency of viral replication and assembly and promote virus proliferation in cells. On the other hand, CoV-induced LLPS can isolate host antiviral factors and then escape the host immune response, especially host innate immunity. Based on this understanding, a variety of potential drugs and therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 have been explored to inhibit the proliferation of SARS-CoV-2. However, there is some variability observed among different CoVs, and it remains unclear whether other CoVs exhibit the same mechanism to induce LLPS.

Although there have been some developments in our understanding of the mechanism and function of coronavirus-induced LLPS in recent years, it is worth noting that most studies are descriptive results from in vitro assays. Therefore, future studies will need more established tools to focus on a better mechanistic understanding in vivo. For example, the design of proteins specifically labeled with viral components for real-time observation in cells will provide a basis to further understand the process of LLPS initiation under natural coronavirus infection conditions and provide a basis for the design of intervention strategies.

The molecular mechanism through which coronaviruses evade the host’s antiviral innate immunity through LLPS is currently a research hotspot in virology. CoV N proteins are the most synthesized proteins in virus-infected host cells. They play a crucial role in viral replication and assembly and are extensively involved in regulating host cell biological processes [43]. Several CoV N proteins have been confirmed to inhibit the host innate immunity in cells. Due to the high degree of variability in CoVs, differences between viral strains may impact their ability to evade host immunity. This needs further investigation. Moreover, there is still limited understanding of the molecular mechanisms through which LLPS influences the host antiviral innate immune response. In the future, researchers can employ a variety of strategies to address the aforementioned issues. For example, high-throughput screening and gene editing technologies are being used to identify and validate the key factors involved in LLPS and their mechanisms of action. Researchers should conduct collaborative, interdisciplinary studies to integrate knowledge from biology, chemistry, physics, and other fields to fully understand the molecular mechanisms through which coronaviruses evade the immune system.

Author Contributions

L.J. and W.Z. conceived and designed this review. Y.W., L.Z. and X.W. (Xiaohan Wu) performed the data collection. Y.W. and L.Z. collected the data and wrote the manuscript equally. S.Y., X.W. (Xiaochun Wang), Q.S. and Y.L. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32102682), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2022M721391), and the Natural Science Foundation of Higher Education of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. 21KJB230006).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Y.G.; Zhang, H. Phase separation in membrane biology: The interplay between membrane-bound organelles and membraneless condensates. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: Organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeynaems, S.; Alberti, S.; Fawzi, N.L.; Mittag, T.; Polymenidou, M.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J.; Shorter, J.; Wolozin, B.; Van Den Bosch, L.; et al. Protein phase separation: A new phase in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, T.; Du, Y.; Xing, C.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, R.F. Toll-like receptor signaling and its role in cell-mediated immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 812774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesheh, M.M.; Hosseini, P.; Soltani, S.; Zandi, M. An overview on the seven pathogenic human coronaviruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etibor, T.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Amorim, M.J. Liquid biomolecular condensates and viral lifecycles: Review and perspectives. Viruses 2021, 13, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Yang, J.; Cristea, I.M. Liquid-liquid phase separation in innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2024, 45, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulswit, R.J.; de Haan, C.A.; Bosch, B.J. Coronavirus spike protein and tropism changes. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Peng, Y.; Huang, B.; Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Niu, P.; Meng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Genome composition and divergence of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) originating in china. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V.; Saxena, S.; Panda, P.S. Basic virology of SARS-CoV-2. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 40, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belouzard, S.; Millet, J.K.; Licitra, B.N.; Whittaker, G.R. Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses 2012, 4, 1011–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.R.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Lin, H. Cell entry of animal coronaviruses. Viruses 2021, 13, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Lan, H.Y. Signaling mechanisms of sars-cov-2 nucleocapsid protein in viral infection, cell death and inflammation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4704–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Dong, H.; Jiao, R.; Zhu, X.; Shi, H.; Chen, J.; Shi, D.; Liu, J.; Jing, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. The tgev membrane protein interacts with hsc70 to direct virus internalization through clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0012823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, B.A.; Chen, V.; Cochrane, A.W.; Parent, L.J.; Mouland, A.J. Liquid-liquid phase separation of nucleocapsid proteins during SARS-CoV-2 and HIV-1 replication. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 111968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of sars-cov-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Dellibovi-Ragheb, T.A.; Kerviel, A.; Pak, E.; Qiu, Q.; Fisher, M.; Takvorian, P.M.; Bleck, C.; Hsu, V.W.; Fehr, A.R.; et al. Β-coronaviruses use lysosomes for egress instead of the biosynthetic secretory pathway. Cell 2020, 183, 1520–1535.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdikari, T.M.; Murthy, A.C.; Ryan, V.H.; Watters, S.; Naik, M.T.; Fawzi, N.L. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation stimulated by RNA and partitions into phases of human ribonucleoproteins. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazewski, C.; Perez, R.E.; Fish, E.N.; Platanias, L.C. Type i interferon (ifn)-regulated activation of canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 606456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarante-Mendes, G.P.; Adjemian, S.; Branco, L.M.; Zanetti, L.C.; Weinlich, R.; Bortoluci, K.R. Pattern recognition receptors and the host cell death molecular machinery. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ma, L.; Yang, S.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Z.; Xie, W.; Jin, S.; et al. Phase-separated nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 suppresses cgas-DNA recognition by disrupting cgas-g3bp1 complex. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Xia, T.; Xing, J.Q.; Yin, L.H.; Li, X.W.; Pan, J.; Liu, J.Y.; Sun, L.M.; Wang, M.; Li, T.; et al. The stress granule protein g3bp1 promotes pre-condensation of cgas to allow rapid responses to DNA. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e53166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; McAtee, C.K.; Su, X. Phase separation in immune signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, L.; Shen, J.; Zhai, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Yi, M.; Deng, X.; Ruan, Z.; Fang, R.; Chen, Z.; et al. The sting phase-separator suppresses innate immune signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubrich, K.; Augsten, S.; Simon, B.; Masiewicz, P.; Perez, K.; Lethier, M.; Rittinger, K.; Gabel, F.; Cusack, S.; Hennig, J. Rna binding regulates trim25-mediated rig-i ubiquitylation. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Shen, W.; Hu, J.; Cai, S.; Zhang, C.; Jin, S.; Guan, X.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Cui, J. Molecular mechanisms and cellular functions of liquid-liquid phase separation during antiviral immune responses. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1162211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.; Fang, X.; Sun, W.; Ma, Z.; Dai, T.; Wang, S.; Zong, Z.; Huang, H.; Ru, H.; Lu, H.; et al. Deactylation by sirt1 enables liquid-liquid phase separation of irf3/irf7 in innate antiviral immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1193–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The nlrp3 inflammasome: An overview of mechanisms of activation and regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Li, R.; Negro, R.; Cheng, J.; Vora, S.M.; Fu, T.M.; Wang, A.; He, K.; Andreeva, L.; Gao, P.; et al. Phase separation drives RNA virus-induced activation of the nlrp6 inflammasome. Cell 2021, 184, 5759–5774.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, O.; Staeheli, P.; Schwemmle, M.; Kochs, G. Mx gtpases: Dynamin-like antiviral machines of innate immunity. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozawa, T.; Matsunaga, K.; Izumi, T.; Shigehisa, N.; Uekita, T.; Taoka, M.; Ichimura, T. Ubiquitination-coupled liquid phase separation regulates the accumulation of the trim family of ubiquitin ligases into cytoplasmic bodies. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ma, L.; Cai, S.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Jin, S.; Xie, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; et al. RNA-induced liquid phase separation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein facilitates nf-κb hyper-activation and inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Ea, C.K.; Fang, Y.; Chen, Z.J. Liquid phase separation of nemo induced by polyubiquitin chains activates nf-κb. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2415–2426.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huoh, Y.S.; Hur, S. Death domain fold proteins in immune signaling and transcriptional regulation. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 4082–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quek, R.T.; Hardy, K.S.; Walker, S.G.; Nguyen, D.T.; de Almeida Magalhães, T.; Salic, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S.M.; Silver, P.A.; Mitchison, T.J. Screen for modulation of nucleocapsid protein condensation identifies small molecules with anti-coronavirus activity. ACS Chem. Biol. 2023, 18, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Jian, T.; Yu, Q.; Zeng, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Llps of fxr proteins drives replication organelle clustering for β-coronaviral proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 223, e202309140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iserman, C.; Roden, C.A.; Boerneke, M.A.; Sealfon, R.S.G.; McLaughlin, G.A.; Jungreis, I.; Fritch, E.J.; Hou, Y.J.; Ekena, J.; Weidmann, C.A.; et al. Genomic rna elements drive phase separation of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid. Mol. Cell 2020, 80, 1078–1091.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, D.; Hassan, S.A.; Nguyen, A.; Chen, J.; Piszczek, G.; Schuck, P. A conserved oligomerization domain in the disordered linker of coronavirus nucleocapsid proteins. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubuk, J.; Alston, J.J.; Incicco, J.J.; Singh, S.; Stuchell-Brereton, M.D.; Ward, M.D.; Zimmerman, M.I.; Vithani, N.; Griffith, D.; Wagoner, J.A.; et al. The sars-cov-2 nucleocapsid protein is dynamic, disordered, and phase separates with RNA. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, C.; Xu, Q.; Yin, H. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation into stress granules through its n-terminal intrinsically disordered region. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, M.; Song, J. Ctd of SARS-CoV-2 n protein is a cryptic domain for binding atp and nucleic acid that interplay in modulating phase separation. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein and its role in viral structure, biological functions, and a potential target for drug or vaccine mitigation. Viruses 2021, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Runge, B.; Russell, R.W.; Movellan, K.T.; Calero, D.; Zeinalilathori, S.; Quinn, C.M.; Lu, M.; Calero, G.; Gronenborn, A.M.; et al. Atomic-resolution structure of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein n-terminal domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10543–10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Wang, S.; Zong, Z.; Pan, T.; Liu, S.; Mao, W.; Huang, H.; Yan, X.; Yang, B.; He, X.; et al. Trim28-mediated nucleocapsid protein sumoylation enhances SARS-CoV-2 virulence. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Ye, Q.; Singh, D.; Cao, Y.; Diedrich, J.K.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Villa, E.; Cleveland, D.W.; Corbett, K.D. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein forms mutually exclusive condensates with RNA and the membrane-associated m protein. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ling, X.; Zhang, C.; Zou, J.; Luo, B.; Luo, Y.; Jia, X.; Jia, G.; Zhang, M.; Hu, J.; et al. Modular characterization of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein domain functions in nucleocapsid-like assembly. Mol. Biomed. 2023, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlova, J.; Knizhnik, E.; Manuvera, V.; Severov, V.; Shirokov, D.; Grafskaia, E.; Bobrovsky, P.; Matyugina, E.; Khandazhinskaya, A.; Kozlovskaya, L.; et al. Nucleoside analogs and perylene derivatives modulate phase separation of SARS-CoV-2 n protein and genomic rna in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, M.; Li, T.; Song, J. Atp and nucleic acids competitively modulate llps of the SARS-CoV2 nucleocapsid protein. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brant, A.C.; Tian, W.; Majerciak, V.; Yang, W.; Zheng, Z.M. SARS-CoV-2: From its discovery to genome structure, transcription, and replication. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Ma, C.; Jiang, H.; Zuo, T.; Chen, R.; Ke, Y.; Cheng, H.; et al. Multiscale characterization reveals oligomerization dependent phase separation of primer-independent rna polymerase nsp8 from SARS-CoV-2. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Sun, C.; Zhang, S. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein: Its role in the viral life cycle, structure and functions, and use as a potential target in the development of vaccines and diagnostics. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lei, X.; Jiang, Z.; Humphries, F.; Parsi, K.M.; Mustone, N.J.; Ramos, I.; Mutetwa, T.; Fernandez-Sesma, A.; Maehr, R.; et al. Cellular nucleic acid-binding protein restricts SARS-CoV-2 by regulating interferon and disrupting RNA-protein condensates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2308355120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblete-Durán, N.; Prades-Pérez, Y.; Vera-Otarola, J.; Soto-Rifo, R.; Valiente-Echeverría, F. Who regulates whom? An overview of RNA granules and viral infections. Viruses 2016, 8, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Deng, J.; Han, L.; Zhuang, M.W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Nan, M.L.; Xiao, Y.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 nsp5 and n protein counteract the rig-i signaling pathway by suppressing the formation of stress granules. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolliver, S.M.; Kleer, M.; Bui-Marinos, M.P.; Ying, S.; Corcoran, J.A.; Khaperskyy, D.A. Nsp1 proteins of human coronaviruses hcov-oc43 and SARS-CoV2 inhibit stress granule formation. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1011041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yu, Y.; Sun, L.M.; Xing, J.Q.; Li, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Xue, W.; Xia, T.; et al. Gcg inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication by disrupting the liquid phase condensation of its nucleocapsid protein. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, R.; Tsuno, S.; Irokawa, H.; Sumitomo, K.; Han, T.; Sato, Y.; Nishizawa, S.; Takeda, K.; Kuge, S. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein-RNA interaction by guanosine oligomeric RNA. J. Biochem. 2023, 173, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Prasad, K.; AlAsmari, A.F.; Alharbi, M.; Rashid, S.; Kumar, V. Genomics-guided targeting of stress granule proteins g3bp1/2 to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 propagation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 190, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Mathieu, C.; Kolaitis, R.M.; Zhang, P.; Messing, J.; Yurtsever, U.; Yang, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Pan, Q.; et al. G3bp1 is a tunable switch that triggers phase separation to assemble stress granules. Cell 2020, 181, 325–345.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, H.; Jalin, J.; He, Z.; Wang, R.; Huang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Dai, B.; Li, D. Nucleocapsid proteins from human coronaviruses possess phase separation capabilities and promote fus pathological aggregation. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somasekharan, S.P.; Gleave, M. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein interacts with immunoregulators and stress granules and phase separates to form liquid droplets. FEBS Lett. 2021, 595, 2872–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).