Abstract

Despite the widespread agreement on the importance of dynamic capabilities to the success of mergers and acquisitions, little is known about how these capabilities may contribute to the business model’s innovation of an acquirer. The purpose of the paper is to clarify the role of dynamic capabilities in business model innovation of acquirer’s company in mergers and acquisitions of technology-advanced firms. Empirically, the author examined the role of dynamic capabilities in the transformation of operationalized components of the business model of the two acquirers (Samsung and Microsoft) by means of the acquisition of technology-advanced firms (Harman and LinkedIn) in 2016. Drawing on extensive qualitative data, the author developed a practice-driven model as a practical guide for scholars who have been studying dynamic capabilities and business models, as well as for those who are new to the field. The resulting model advances the discourse on dynamic capabilities. The presented conceptual model encourages practitioners to grasp an exact relationship between the micro-foundations of each perspective. Overall, the paper deepens the conversation at the nexus of dynamic capabilities and business model innovation in pursuing a new customer value proposition in the merger and acquisition processes and thereby exploiting a competitive advantage.

1. Introduction

A focal firm’s growth strategies and performance are greatly influenced by the integrative type of strategies: Collaborative (alliances, networks, joint ventures) or consolidative (mergers, acquisitions), to foster the innovation and to deliver new customer value propositions. In recent years, collaborative and consolidation strategies have received great attention in strategic management literature. What is the research gap in the existing literature on dynamic capabilities and business models? First, there are very few research papers that applied the dynamic capabilities framework as a tool of the business analysis of a reinvention of a business model’s components of an acquirer’s company in the M&A processes. Second, the reinvention of business models of acquirers is still an open area for research due to the following reasons. Researchers in strategic management argue that the performance outcome of a specific growth strategy is usually affected by the dynamic capabilities and business models (BM) [1,2,3]. According to Foss and Saebi, we do not yet know what the drivers of the business model innovation (BMI) are and under which circumstances BMI underpins competitive advantages [4]. The goal of this article is to understand the role of dynamic capabilities as drivers of business model innovation of acquirer’s company in mergers and acquisitions of technology-advanced firms. Capturing valuable insights from the dynamic capability’s framework [5], business model canvas [2], and BMI theory the author to integrate three theoretical perspectives in the cohesive conceptual model. The paper is organized as follows. At the beginning of the paper, the author explored the recent scientific discussion on the role of dynamic capabilities in the field of strategic management, building blocks of the BM of focal company and capabilities needed to its transformation in the context of M&A processes. Based on the literature review in depth, the author designed the research methodology and posed two research questions as follows. What triggers off dynamic capabilities, particularly in M&A of technology advanced firms? What is the role of dynamic capabilities as drivers of BMI in M&A of technology-advanced firms? To answer research questions, the author selected two inductive (illustrative) case studies of the most successful companies of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) industry and the more intriguing their M&A deals, namely, Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn at the end of 2016, Samsung’s acquisition of Harman International Industries in 2017. There are three main sources of information have been used in the research: Business study literature, news media, and company report. Two cases have been compiled in one cohesive research paper due to the similarities of triggers of the deployment of dynamic capabilities and cause the transformation of a business model and their business model innovation, namely, Samsung delay entry in connected cars business, Microsoft’s delay entry on mobile ecosystems. Two cases studies have also been compiled in one cohesive research paper due to similar roles of dynamic capabilities as drivers of BMI in M&A of technology-advanced firms, namely, to sense a new demand, capture new resources and partnerships, transform channels and customers’ relationship, and deliver a new customer value proposition to new users’ base, particularly by means of acquiring of new technologies, advanced an engineering team. Having used case study research findings, the author has developed a conceptual model for future research that integrates dynamic capabilities frameworks (sensing, seizing, and transforming) [5], nine building blocks of BM canvas [2], and strategic management framework (scope, resources, organization), to demonstrate the role of dynamic capabilities in BMI in the M&A process. At the end of the paper, the author discussed empirical findings, limitations, and future work.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dynamic Capabilities

Capabilities are generally defined as the capacity to undertake activities, and thus, capabilities are latent until called into use [6]. Dynamic capabilities refer to a subset of capabilities directed toward strategic change, both at the organizational and individual level [7]. The recent scientific discussion in the field of strategic management broadly favors the idea of dynamic capabilities in order to overcome the potential rigidities of an organizational capability building [8]. Teece et al. define dynamic capabilities as “the ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments”, which became a dominant research agenda on how to sustain advantages in a complex and volatile environment [9,10]. Later, for practical purposes of business analysis, Teece proposed a dynamic capabilities framework [11] as three categories of first order entrepreneurial capabilities: Sensing, identifying, and assessing new emerging opportunities; then, seizing necessary resources to address, grasp, and capitalize its opportunities, and transforming the organization’s tangible and intangible assets, renewing core competencies, and developing new customer value propositions. Thus, a corporation engages with the reconfiguration of resources and activities [12] to match the requirements of a changing environment. What is more, dynamic capabilities enable a corporation to direct its activities towards producing new goods or services that are likely to be in high demand [13]. Firms with dynamic capabilities have “entrepreneurial management and transformational leadership [14] (p. 8)”. Lessard et al. [15] also argue that dynamic capabilities (DCs) are based on both managerial cognition and leadership capabilities along with organizational routines. Adner and Helfat [16] introduced and defined dynamic managerial capabilities (DMC) as those “capabilities with which managers build, integrate, and reconfigure organizational resources and competences”. What is more, pursuing horizontal integration by M&A strategies to the extent of the range of products and/or service segments that a firm serves within its focal market, dynamically capable management teams need such managerial capabilities as sensing and shaping new demand, seizing new resources, and transforming the organization as well as reinventing and implementing new BMI [11]. Teece argues that dynamic capabilities can enable the firms to create and capture value by designing appropriate business models [17]. Value creation through M&A requires the simultaneous identification of target with similar dynamic capabilities on certain dimensions and different dynamic capabilities on other dimensions. Complementarity has been studied in terms of top management team complementarity [18], technological complementarity [19], strategic and market complementarity [20], or product complementarity [21]. However, the study in terms of complementarity of dynamic capabilities in M&A is still waiting for researchers. Teece argues [1] that business models “have considerable significance but are poorly understood - frequently mentioned but rarely analyzed” and establishes his goal ‘to explore their connections to business strategy, innovation management, and economic theory’.

2.2. The Business Model of Acquirer’s Company

Business models characterize the focal firm’s plan for its value creation and capture [22]. In recent years, the business models have received increasing attention from strategy researchers. Slightly adapted ideas on BM by Johnson et al. [23] and Osterwalder and Pigneur [2], Teece proposed three main components of the business model: Cost Model, Revenue Model, and Value proposition [24]. However, the reinvention of business models of acquirers still an open area for research due to the following reasons. Johnson at al. [23] gave excellent ideas on a reinvention of business models and their building blocks for focal companies, but still, a question remains, what capabilities are needed in the reinvention of business models in the M&A process? Pursuing scientific rigor and helping practitioners to re-invent their BMs, Amit and Zott [25] integrated dynamic capabilities with the business model design process, but what about re-invention of building blocks of business models in the M&A process? However, there is silence about what dynamic capabilities are needed for that. Recent research by Ingino et al. [26] on business model innovation for sustainability by exploring evolutionary and radical approaches through dynamic capabilities gave practical and theoretical insights into the business model, innovation, and sustainability literature. With respect to brilliant contributors to dynamic capabilities and BMs’ frameworks, there is still a gap in understanding about what and how dynamic capabilities leads to new cost structure and revenue streams and how dynamic capabilities foster new value proposition of the acquirer’s company in M&A process, and therefore lead to competitive sustainability. We have to understand how dynamic capabilities reinvent the building blocks of BM of the acquirer’s company.

2.3. Business Model Innovation

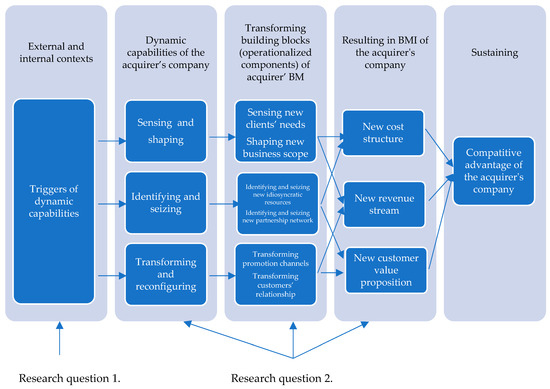

Researchers perceive the level of innovation of the BM differently. For example, Johnson et al. [23] believe that BMI is pointless unless it is new to the company and novel or game-changing to the industry and market in a certain way. On the other hand, Amit and Zott [25] suggest that BMI can also be only incremental in its characteristics, when a company finds a way to realize the economy of scale and affect the efficiency or boost the quality, for example. The BMI often implies reinforcing some of the components or complimenting the core business. Therefore, the new BM does not imply that the existing business model is threatened or should be changed dramatically [27]. Amit and Zott argue that focal company can innovate BM by redefining (a) content (adding new activities), (b) structure (linking activities differently), and (c) governance (changing parties that do the activities) [28]. There are few reviews on Business Model Innovation in M&A of technology advanced firms. Furthermore, a more comprehensive review and empirical research of the BMI in M&A of technology advanced firms’ deals are warranted. What exactly is meant by the reinvention of building blocks of BM? The reinvention of building blocks of business is meant the process of the transformation of the most important activities, capabilities, and resources of the company to reduce cost, to increase revenue stream, to deliver new customer value proposition, and thereby to sustain competitive advantages. How dynamic capabilities support a reinvention of building blocks of BM? There are three sets of dynamic capabilities which should be developed to transform and reinvent a business model of an acquirer to achieve competitive advantage. The first set of dynamic capabilities (sensing and shaping) is contributing to select new key activities and new customer segments, thereby contributing to an acquirer to shape emerging market demand and new technologies needed. The second set of dynamic capabilities (identifying and seizing) is supporting an acquirer’s company to obtain new key idiosyncratic resources and capabilities and to extend a partnership’s networks. The third set of dynamic capabilities (transforming and reconfiguring) is contributing an acquirer’s company to transform the mode of customer retention and sale force and thus, to deliver value to the customer and capture value for stakeholders. As a result of those transformations processes, the acquirer’s company results in new cost structure, new revenue stream, and new customer value proposition and can sustain a new competitive advantage. The conceptual model of the research is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model of current research (Source: developed by author).

3. Research Design and Methodology

Yin defines the case study research method as an empirical inquiry that investigates a phenomenon within its real-life context [29]. Some critics suggest that case study research is useful only as an exploratory tool or for establishing a hypothesis; some would claim that it is unscientific [30]. When it comes to the validity of qualitative case study research, the validity refers to the extent to which the qualitative research results: Accurately represent the collected data (internal validity) can be generalized or transferred to other contexts or settings (external validity) [30]. Having explored two case studies, the author has asked two research questions as follows: What triggers off dynamic capabilities, particularly, in M&A of technology advanced firms? What is the role of dynamic capabilities as drivers of BMI? The author answered the research questions by exploring two inductive (illustrative) cases studies that help an outsider understand the critical role of dynamic capabilities in the reinvention of a BM in M&A in technology advanced firms. While single-case studies can richly describe the existence of a phenomenon [31], multiple-case studies typically provide a stronger base for theory building [29]. Firstly, to answer research questions, the author did the contextual content analysis, which relied on an archival search that included financial statements, annual reports, internal documents, industry publications, and CEO statements to get at a micro-level understanding, which really boosts data and the better understanding of the micro-foundations of DC of acquirers and targets. The current paper relied on an extensive search of secondary data. The key to secondary data analysis is to apply theoretical knowledge and conceptual skills to utilize existing data to address the research questions. The major advantages associated with secondary analysis are the cost-effectiveness and convenience it provides [32]. A major disadvantage of using secondary data is that the secondary researcher did not participate in the data collection process and does not exactly know how it was conducted. However, the obvious benefits of using secondary data can be overshadowed by its limitations [33]. Original survey research rarely uses all of the data collected and this unused data can provide answers or different perspectives to other questions or issues [32]. In a time where vast amounts of data are being collected and archived by researchers all over the world, the practicality of utilizing existing data for research is becoming more prevalent [32,34].

The aim of the content analysis of inductive (illustrative) cases studies is to explicate the relationship between dynamic capability and reinvention of acquirer’s business model, and thus, sustaining competitive advantage. For this study, the author has chosen human scored systems and individual work count systems [35,36]. The unit of analysis is dynamic capabilities. To answer the first research question, then the author has chosen human scored systems and classified text into three specific classification categories, namely, sensing, seizing, and transforming dynamic capabilities. When it comes to the format of the presentation, the author adopted a conceptual frame developed by Teece [37]. The conceptual frame helped to unravel data in the text that the author has collected in search of similarities and complementarity of the micro-foundations of the dynamic capabilities of both companies. To answer second research questions, the author applied an individual work count system, the text has been allocated within nine building blocks of the BM of both companies (as semantically equivalent categories) and identified compatibilities and complementarity of companies’ business models. Then, the author has allocated operationalized components of the business model into each cluster of dynamic capabilities (sensing, seizing, and transforming) to demonstrate the role of dynamic capabilities as drivers of the innovation of business model of the acquirers’ companies. The second stage of research involves a demonstration of the development process of the new conceptual model of research by using literature research outcomes and secondary data content analysis findings. Therefore, the second stage of the research involves a demonstration of a conceptual model of research that bridges dynamic capabilities framework with a business model canvas and demonstrates the role of dynamic capabilities as drivers of business model innovation in M&A of technology advanced firms. The proposed conceptual practice-driven model can be as a practical guide for scholars who have been studying DCs, BMs, and BMI, as well as for those who are new to the field. The paper discusses and interprets the results of the research in the next subchapter. The paper discusses and interprets the results of the qualitative and explorative research in the next subchapters.

4. Case Analysis to Interpretation

4.1. Samsung’s Acquisition of Harman in November 2016

14.11.2016 Samsung announced the acquisition of Harman International Industries, an American automotive technology manufacturer, for $8 billion in cash. Therefore, Samsung’s foray into the automotive industry, starting with the biggest acquisition in the company’s entire history. According to new research released today by Gartner, connected car production is growing rapidly in both mature and emerging automobile markets. Harman’s acquisition by Samsung is one which involves combining business models and dynamic capabilities that would ultimately help to develop new customer value proposition and to provide their users the ‘ultimate professional experience’. Having explored the reinvention of building blocks of the BM of the acquirer, as well as to answer two research questions, the author applied two steps of research.

4.1.1. First Research Question: What Triggers off Dynamic Capabilities, Particularly in M&A of Technology Advanced Firms?

The author has identified two triggers of the dynamic capabilities in the M&A of technology-advanced firms. The first triggers are weak transformation capabilities of the acquirer’s company. Samsung was not always successful in transformation or reconfiguring resources. After losing more than 5 billion thanks to the self-inflaming Note 7 device, Samsung is trying something that can well outshine the Group reputation as a leading smartphone manufacturer. However, Samsung was the latest technology company to enter the fray by manufacturing electronic parts for the automotive industry. Additionally, what Samsung could do recently, with the help of Harman’s well-established market position, is to tap into the area of automotive connectivity faster than Apple, or any other rival, and bring real innovation to this lagging, but important, part of car technology.

Second triggers are similarities and complementarities of dynamic capabilities of an acquirer and target companies. Technologies of Samsung and Harman are mutually complementary, thereby providing them with a significant market edge. There were many similarities found among the dynamic capabilities of both companies. Both companies were successful to sense emerging market demand on to connected the car, to seize opportunities by developing new advanced products, platforms, and services, keeping leading positions and get competitive advantages. Thereby, the dynamic capabilities of the two companies are quite similar. To conclude, the success of Harman’s acquisition by Samsung is gouged by their strong similarities and complementarities. For the sake of visualization, the answers to the first research question are given in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Dynamic capabilities at Samsung to develop electric cars and its components before the acquisition of Harman.

Table 2.

Dynamic capabilities at Harman to develop connected car solution before the acquisition by Samsung.

4.1.2. Second Research Questions: What Is the Role of Dynamic Capabilities as Drivers of BMI?

Having analyzed both Samsung and Harman International Industries building blocks of business models, the research answered the second research questions. The dynamic capabilities of Samsung helped them to transform the building blocks of BM as follows. Thereby, Samsung sensed new customers’ segments for their business: Smart vehicles that offer sophisticated embedded electronics and new key activities that should be developed. Samsung seized new key (idiosyncratic) resources by Harman’s acquisition, as well as seizing Harman’s customers and to the key partners’ network. Hence, Samsung reconfigured new customers’ segments and marketing promotion channels. Thereby, Samsung results in the new customer value proposition, providing new offerings for their current and new customers. Samsung is an ideal partner for Harman and this transaction will provide tremendous benefits to our automotive customers and consumers around the world. To conclude, dynamic capabilities were real drivers of BM innovation of Samsung and underpinned to reduce cost, to generate the new revenue stream, to deliver a new value proposition, and thereby, to create a new sustained competitive advantage. Thereby, the answers to the second research question are given in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

The role of dynamic capabilities of Samsung as drivers of the business model innovation in the acquisition of Harman.

Table 4.

Bridging perspectives together: the reinvention of Samsung business model (BM) acquiring Harman and micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities underpinning a transformation of BM building blocks.

4.2. Microsoft’s Acquisition of LinkedIn in 2016

In December 2016, Microsoft completed the acquisition of LinkedIn.com, for which they paid more than $26 billion. LinkedIn’s more than 400 million professional users were the demographic Microsoft needed to help grow its Office products and services. LinkedIn’s users also offered opportunities for Microsoft to develop its cloud and customer relationship management initiatives [38]. The acquisition benefitted LinkedIn by providing the company with capital and opportunities to be incorporated into Microsoft’s Office products and service. LinkedIn’s acquisition by Microsoft is one which involves combining and aligning dynamic capabilities and business models and that would ultimately help to complement and to develop a new customer value proposition. In this respect, Microsoft would use LinkedIn’s technology and integrate it into its software to provide its users with the ‘ultimate professional experience’.

4.2.1. First Research Question: What Triggers off Dynamic Capabilities, Particularly, in M&A of Technology Advanced Firms?

The author has also found two triggers of the dynamic capabilities of the M&A of technology advanced firms. First triggers are weak transformation capabilities of both companies: Microsoft’s a delayed entry into mobile ecosystems and huge operating losses of LinkedIn. Second triggers are similarities and complementarities of dynamic capabilities of an acquirer and a target. Both companies were successful to sense emerging market demands, to seize opportunities by developing products and platforms, keeping leading positions. Thereby, the dynamic capabilities of sensing and seizing of two companies are quite similar. However, companies were not always successful in transformation or reshaping resources. One of Microsoft’s weaknesses is a low mobile presence. For instance, despite the Nokia acquisition and Surface tablet introduction, Microsoft continues behind iOS and Google mobile ecosystems. In contrast, LinkedIn provided a mobile-based assess to the professional users’ database. LinkedIn successfully runs a social network on mobile devices with a high mobile presence (60% of users). However, LinkedIn’s net losses have been sharply increased from $15.7 million in 2014 to $166 million in 2015. Therefore, Microsoft can provide resources for future LinkedIn development and at the same time can develop its own mobile ecosystem. The answers to the first research question are given in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Dynamic capabilities at Microsoft to develop mobile ecosystem before the acquisition of Linked In.

Table 6.

Dynamic capabilities at LinkedIn to develop social network before the acquisition by Microsoft.

4.2.2. Second Research Questions: What Is the Role of Dynamic Capabilities as Drivers of BMI?

Having analyzed companies’ in depth, the research answered the second research questions. Acquiring LinkedIn is a defensive play by Microsoft; it keeps LinkedIn out of the hands of Google, Amazon, Salesforce and other potential business-focused rivals. Joining their idiosyncratic resources and aligning their dynamic capabilities, Microsoft and LinkedIn complement customer value propositions of each other and help to sustain competitive advantage in a mobile ecosystem. Having explored DCs and BMs of Microsoft and LinkedIn, the author found that the acquisition enabled a series of strategic innovations to integrate Microsoft products with LinkedIn functionality and vice-versa. LinkedIn is an attractive platform for Microsoft to sell additional business services/apps such as Microsoft Dynamics products. Therefore, the second research question has been answered empirically, as shown in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

The role of dynamic capabilities of Microsoft as drivers of the business model innovation by acquiring LinkedIn.

Table 8.

Bridging perspectives together: the reinvention of Microsoft business model (BM) acquiring LinkedIn and micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities underpinning a transformation of BM building blocks.

There are three sets of dynamic capabilities to be developed to reinvent a business model of an acquirer to achieve a competitive advantage. The first set of sensing and shaping is contributing to select new key activities and new customer segments, thereby contributing to an acquirer to shape emerging market demands and new technologies. The second set of dynamic capabilities (seizing) is supporting an acquirer’s company to obtain new key idiosyncratic resources and to extend a partnership’s networks. The third set of dynamic capabilities (reconfiguration or transforming) is contributing an acquirer’s company to transform new customer relationships and promotion channels and thus, to deliver the new customer value proposition. That is what Microsoft did with LinkedIn at the end of 2016, as shown in Table 8.

Today Microsoft’s earnings provide fresh proof that the LinkedIn deal is paying off [39]. LinkedIn’s revenue growth in 2018 is now much higher than it was when Microsoft bought the company. Microsoft disclosed that LinkedIn’s revenue rose 37% annually for the second quarter in 2018 in a row and totaled $1.46 billion [39].

5. Findings and Discussion

Ambrosini et al. argue that evidence of regenerative dynamic capabilities was triggered by performance problems [40]. This paper addresses the latter issue in great depth. The author used contextual content analysis [41] to answer two research questions. The contextual analysis provided a comprehensive solution to the challenge of identifying and categorizing key textual data [42]. Content analysis transformed unstructured data into organized information to give the readers a competitive edge [42].

Having researched the first inductive case study, the paper explored the role of dynamic capabilities in the reinvention of the business model of merging company (Samsung) by means of acquisition of technologically advanced firm (Harman). Samsung is sensing a new customers’ demand and shaping a new key activity needed to satisfy this demand. Samsung is identifying, seizing, and acquiring strategically valuable resources. Acquiring the automotive electronics-maker Harman will make great strides into this growing market. Dynamic capabilities of Samsung and Harman are aligning and allowing them to improve existing products by sharing engineers’ experience, advanced technologies, and broad users’ base, and therefore, underpinning the reinvention of building blocks of the business model of Samsung.

Having examined the second inductive case study, the paper explored the role of dynamic capabilities in the M&A process of technology-advanced firms as drivers of the business model innovation of Microsoft. The first set of dynamic capabilities is sensing and shaping, which contribute to an acquirer to shape emerging market demand and new technologies. Concerning LinkedIn’s business model, the company has three customer segments. The first and probably biggest one is the number of internet users who visit their website and create a profile on it. The second segment is the recruiters that are looking for suitable and potential new employees and the third and last one is the advertiser. In comparison to LinkedIn, Microsoft’s customers consist of individual consumers, organizations, OEMs (original equipment manufacturers), business users, and application developers. Thereby, Microsoft sensed new customers’ segments and new key activities. The customer segments may not be identical, but some of them are quite similar and compatible. The most compatible segment for both companies is business users. LinkedIn responds to them by performing as a business-related platform in the social networking area, while Microsoft has a lot of potential customers for their products and cloud-based offerings in this segment. Furthermore, LinkedIn’s key activity mainly consists of mobile platform development. As a career-oriented network, its essential value is in the number of monthly active users. Therefore, a constantly improved mobile platform is necessary to increase the number of users over time and which keeps them engaged and active on the site.

The second set of dynamic capabilities (seizing) is supporting an acquirer’s company to obtain new key idiosyncratic resources and to extend a partnership’s networks. Compared to LinkedIn, Microsoft’s key activities are software development and marketing. Especially, the software is the company’s biggest business segment and consequently needs to be renewed and improved on a constant basis. Even though the companies’ key activities differ, they are still related to the same task of investing in technology development and can build another compatibility. Moreover, LinkedIn’s main costs are associated with keeping the platform online as their platform can be considered as their key resource. Therefore, the company also invests in R&D for the platform development to find ways to increase its production value to its customer segments. In comparison to this, marketing and sales is a rather small cost item.

The third set of dynamic capabilities (reconfiguration or transforming) is contributing to Microsoft’s business model innovation, especially the transformation of its marketing and sales promotion channels of its products and services and customer relationship management. There are important building blocks of business models of Microsoft that have been reinvented. In consequence, Microsoft can support and push LinkedIn’s marketing activities in order to help them make their platform even more successful and popular. This provides another huge compatibility for the business models of two companies, as LinkedIn and Microsoft are both constantly aiming to improve their product value to their customer segments.

What novel have we learned that goes beyond these existing frameworks of dynamic capabilities and business models? How do we need to change these frameworks based on insights from the cases? The author found that current research gave us substantially more insights into the role that dynamic capabilities can play in M&A deals and how dynamic capabilities relates to business model innovation of the acquirer’s company. The conceptual model integrates the great corporate strategies triangle: Strong market positions (scope); high-quality resources; and an efficient organization [43], as shown in Figure 1.

The conceptual model integrates dynamic capabilities, building blocks of business model canvas, and business model innovation integration in mergers and acquisitions of technology advanced firms that encourage practitioners to grasp an exact relationship between micro-foundations of each perspective. Thereby, the conceptual model makes dynamic capabilities more visible, tangible and to some extent measurable with the help of a business model canvas.

6. Conclusions, Limitation, and Future Work

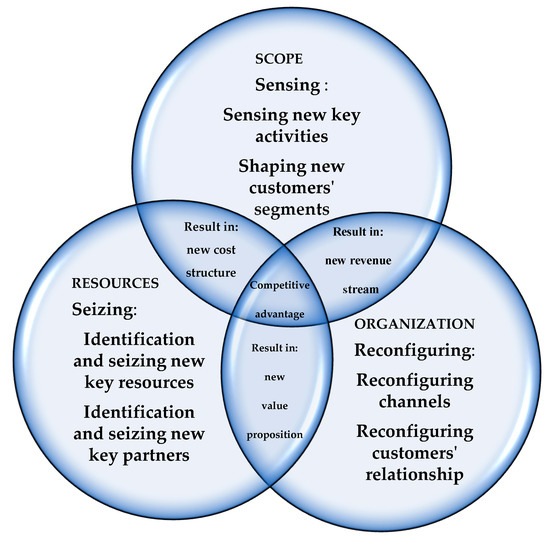

When some dynamic capabilities are missing, a company has the option to develop them internally or purchase them from outside. The current paper contributes to theory and practice by illustrating how this logic works in the M&A process of technologically advanced firms. The model demonstrates that the intersection of sensing and seizing capabilities can result in a new and more efficient cost structure; the intersection of sensing and transforming capabilities can result in the generation of a new revenue stream. The intersection of seizing and transforming capabilities can result in a new customer value proposition. Thereby, the dynamic capabilities are transforming and innovating the acquirer’s business model and underpinning the acquirer’s competitive advantage. The proposed conceptual model (Figure 2) extends its application to M&A deals of technologically advanced firms. Therefore, the primary theoretical contribution is the dynamic capabilities framework as a tool of the business analysis of a reinvention of a business model of an acquirer company in M&A processes. The paper contributes a fresh view of the importance of acquisition based dynamic capabilities and their role in changing the business model of a merging company. What is more, the paper has contributed to the interest of the Strategy Practice group of Strategic Management Society by answering questions that the group attempted to answer: What are the capabilities required to perform strategy work and what are the micro-foundations of the activities involved in the doing of strategy? Namely, the paper clarifies micro-foundations of acquisition based dynamic capabilities that underpin the reinvention of a business model in pursuing innovation.

Figure 2.

Integration of dynamic capabilities framework and a reinvention of business model’s components in the process of mergers & acquisitions: a conceptual model for a future research (Source: Developed by author).

When it comes to managerial contribution, the presented conceptual model for future research in Figure 2 encourages practitioners to grasp an exact relationship between micro-foundations of each perspective: Dynamic capabilities and the process of the reinvention of a business model. The conceptual model for future research given in Figure 2 can be applicable to the acquisition of smaller and less complex firms as well. The model integrates great corporate strategies triangle (scope-recourses-organization) and bridges the dynamic leadership capabilities framework (sensing customer needs-seizing resources-transforming organization) with components of the business model into an integrative framework for the systematic approach to M&A deals in global Information and Communication Technologies’ battles. The current research provided the application of the dynamic capabilities’ framework as a tool of the business analysis of the reinvention of a business model’s components of an acquirer’s company in the M&A processes.

There are several strong limitations to the research. Through the small data size and missing validation through a lack of robust analysis of primary data, the current paper serves more as an introduction to the research, then as the results. Thereby, the paper, being of an exploratory and interpretive in nature, raises several opportunities for future research, both in terms of theory development and findings validation. The conceptual model for future research discussed in Figure 2 could also be used to generate a number of hypotheses for further empirical testing using a broader sample and quantitative research methods.

What is more, because changing the BM is a central top-management task, there is potentially very fruitful link to the top management team (TMT) theory [27]. For example, what dynamic managerial capabilities are more needed in BMI in the M&A process: Managerial cognition capabilities, social capital, or human capital [44]? What is more important and what are less important dynamic managerial capabilities for decision-making processes in M&A deals (idea, justification, due diligence, and negotiation) and for the integration processes in M&A deals (acquisition integration, and synergy management) [45]? Thereby, the paper, being of an exploratory and interpretive in nature, raises several opportunities for future research, both in terms of theory development and findings validation. The study can also be extended in longitudinal and comparative ways.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The paper support from RISEBA University of Applied Sciences is gratefully acknowledged. Remaining flaws are my own responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy, and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation; Self-Published; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Alton, R.; Rising, C.; Waldeck, A. The Big Idea: The New M&A Playbook. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation: How Far Have We Come, and Where Should We Go? J. Manag. 2017, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management; Oxford University Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3–136. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, C.E.; Finkelstein, S.; Mitchell, M.; Peteraf, M.A.; Singh, H.; Teece, D.J.; Winter, S.G. Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, C.E.; Raubitschekb, R.S. Dynamic and integrative capabilities for profiting from innovation in digital platform-based ecosystems. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreyogg, G.; Kliesch-Eberl, M. How dynamic can organizational capabilities be? Towards a dual-process model of capability dynamization. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities, and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurship, and Dynamic Capabilities: A Review, Model and Research Agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro-foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheenan, N.T.; Foss, N.J. Using Porterian activity analysis to understand organizational capabilities. J. Gen. Manag. 2017, 42, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.; Leih, S. Uncertainty, Innovation, and Dynamic Capabilities. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 8–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, D.; Teece, D.J.; Leih, S. The dynamic capabilities of meta-multinationals. Glob. Strateg. J. 2016, 6, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R.; Helfat, C.E. Corporate effect and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: Enabling technologies, standards, and licensing models in the wireless world. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1367–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, H.A.; Miller, A.; Judge, W.Q. Diversification and top management team complementarity: Is performance improved by merging similar or dissimilar teams? Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makri, M.; Hitt, M.A.; Lane, P.J. Complementary technologies, knowledge relatedness, and invention outcomes in high technology mergers and acquisitions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 602–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Finkelstein, S. The effects of strategic and market complementarity on acquisition performance: Evidence from the U.S. commercial banking industry, 1989–2001. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 617–646. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zajac, E.J. Alliance or acquisition? A dyadic perspective on interfirm resource combinations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1291–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R. Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M.; Kagermann, H. Reinventing your business model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Business Model Design: A Dynamic Capability Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Dynamic Capabilities; Teece, D.J., Leigh, S., Eds.; Oxford Handbooks: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Inigo, E.A.; Albareda, L.; Ritala, P. Business model innovation for sustainability: Exploring evolutionary and radical approaches through dynamic capabilities. Ind. Innov. 2017, 24, 515–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Business models and business model innovation: Between wicked and paradigmatic problems. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Siggelkow, N. Persuasion with case studies. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. Using Secondary Data in Educational and Social Research; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M.P. Secondary Data Analysis: A Method of which the Time Has Come. Qual. Quant. Methods Libr. 2014, 3, 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, L.; Higgins, A.; Andrews, M.W.; Lalor, J.G. Classic grounded theory to analyze secondary data: Reality and reflections. Grounded Theory 2012, 11, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R. A Computerized content analysis in management research: A demonstration of advantages & limitations. J. Manag. 1994, 20, 903–931. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, S.D.; Schnurr, P.P.; Oxman, T.E. Content analysis: A comparison of manual and computerized systems. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 54, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities: A Guide for Managers. Ivey Bus. J 2011. Available online: http://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/dynamic-capabilities-a-guide-for-managers/ (accessed on 29 December 2018).

- Sapersen, J.; Gonzales, M. LinkedIn: Bridging the Global Employment Gap; Ivey Publishing: Western University, London, Canada, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jhosan, E. Microsoft’s Earnings Provide Fresh Proof that the LinkedIn Deal Is Paying off. 2018. The Street. Available online: https://www.thestreet.com/opinion/microsoft-earnings-show-linkedin-deal-is-paying-off-14657542 (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Ambrosini, V.; Bowman, C.; Collier, N. Dynamic capabilities: An exploration of how firms renew their resource base. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, S9–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- SAS® Contextual Analysis. Available online: https://www.sas.com/en_us/software/contextual-analysis.html (accessed on 22 July 2018).

- Collis, D.J.; Montgomery, C.A. Competing on Resources. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 1–13, from the July–August Issue. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. Managerial cognition capabilities and the micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haspeslagh, P.C.; Jemison, D.B. Managing Acquisitions: Creating Value through Corporate Renewal; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).