Abstract

This work presents an asymmetric p-i-p silicon diode structure (a-p-i-p) characterized using the Transient Current Technique (TCT) with a scanning pulsed laser system. The device, fabricated on n-type silicon (3–5 Ω·cm) with two identical p+-doped meandering line electrodes (one of which is obscured by a black resin layer), was tested in photovoltaic mode (zero bias) under laser excitation at 660 nm, 980 nm, and 1064 nm wavelengths. The transient photocurrent response was recorded as the laser spot was scanned across the device surface with 0.01 mm spatial resolution. A pronounced wavelength-dependent response was observed: the shortest wavelength (660 nm) produced the largest transient current signals, while longer wavelengths (980 nm, 1064 nm) yielded progressively weaker responses. This study introduces a fundamentally new design paradigm that enables the p-i-p diode to operate in photovoltaic mode.

1. Introduction

Microelectronic sensor technologies have become indispensable tools across a wide range of modern applications, from environmental and biomedical monitoring to industrial automation and space exploration. Their ability to convert physical, chemical, or biological stimuli into measurable electrical signals has driven the miniaturization and integration of sensing systems into wearable and portable devices. Advances in semiconductor processing, thin-film deposition, and microfabrication techniques have enabled the production of highly sensitive, low-power sensors with diverse functionalities, including pressure, temperature, humidity, and gas detection. These developments have further supported the evolution of the Internet of Things (IoT), where distributed networks of sensors provide continuous, real-time data for smart environments and healthcare systems [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

Among various microelectronic devices, semiconductor diodes remain central to sensor technology due to their controllable charge transport properties and compatibility with standard silicon processing. The ability to tailor diode geometries and doping profiles has led to novel functionalities extending beyond traditional rectification and photodetection. In particular, the exploration of nonconventional diode configurations offers new opportunities to manipulate carrier generation and collection under optical excitation. The present work investigates one such concept—a planar asymmetric p-i-p (a-p-i-p) silicon diode—designed to operate in photovoltaic mode under asymmetric optical access, thereby broadening the functional landscape of microelectronic photonic sensors.

The p–i–p diode is a semiconductor structure consisting of two p-type regions separated by an intrinsic or very lightly doped region [16,17]. Its designation mirrors that of the p–i–n diode, which conventionally refers to a vertical stack of layers where current flows perpendicular to the wafer surface [18,19]. In contrast, the device studied here is a lateral p–i–p configuration fabricated on n-type silicon, in which the conduction path lies parallel to the wafer surface between two identical p+ diffused electrodes.

There have been a number of practical applications of p-i-p structures. Sakata et al. utilize α-Si:H multilayer photoconductors with p-i-p structures in order to obtain high photosensitivity and small photoinduced changes [20]. Zhou et al. integrate p-i-p micro-heaters in silicon mirroring resonators and obtain possible utilization in monitoring optical power in the waveguide [21]. M. W. Geis et al. fabricate the structure of p-i-p phototransistors with an optical response of 50 AW−1 [22]. Zaitsev et al. fabricate a pressure–temperature sensor on the working surface of an anvil made of type IIa natural diamond. The sensing region of the sensor was a buried vertical three-layer p–i–p diode with the i-region containing compensated boron acceptors [23,24]. The p-i-p diode based on diamond was also used for radiation monitoring [25].

A distinguishing feature of the device presented in this paper is the asymmetric optical access: one p+ electrode is covered by a black resin layer, while the other remains exposed. Under illumination, the uncovered side generates a photocurrent, while the masked side is optically inactive. To the best of our knowledge, no prior demonstration of a monolithic p–i–p photovoltaic element with one occluded and one illuminated terminal has been reported.

The reported work challenges the prevailing orthodoxy that useful photovoltaic operation in silicon requires vertical p-i-n geometry. Conventional designs rely on rectifying junctions and unbiased illumination of both terminals, whereas the present device demonstrates for the first time that a monolithic lateral p-i-p diode—with one p+ terminal optically occluded and the other illuminated—can operate in self-powered mode and produce robust photocurrent signals. By establishing that optical masking can break this symmetry and yield a functional single-chip sensor, this study introduces a fundamentally new design paradigm. There are also reported devices which exploit structural asymmetry—specifically the non-centrosymmetric crystal structure of tellurene [26], which is fundamental for the bulk photovoltaic effect (BPVE), and the T-shape geometry with spatial confinement [27], which is essential for manipulating hot carrier dynamics—to achieve their unique and enhanced optoelectronic functions.

To evaluate the spectral and spatial response of this structure, the Transient Current Technique (TCT) with a scanning pulsed laser system was employed [28]. Measurements at 660, 980, and 1064 nm laser wavelengths provide insight into the absorption depth dependence, carrier collection characteristics, and active-area definition of the device. By operating in photovoltaic mode, the device demonstrates a capability for self-powered operation, an attractive feature for sensing applications where external bias and associated leakage currents are undesirable.

2. Materials and Methods

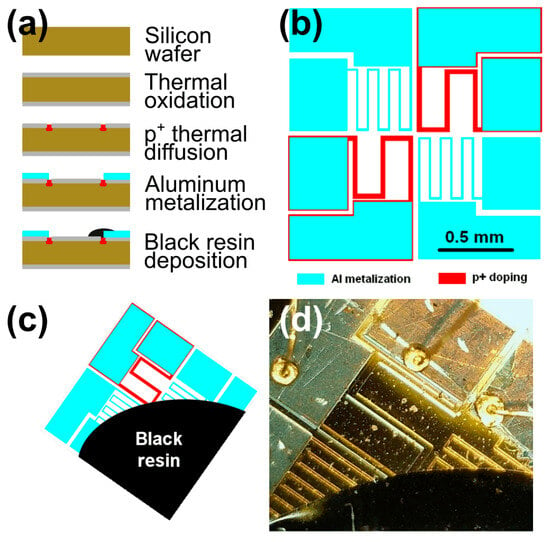

The device was fabricated on a silicon wafer, with a 3″ diameter, 380 μm thickness, n-type, and 3–5 Ωcm resistivity, corresponding to a moderately low doping concentration (on the order of ~1014 cm−3). The wafer went through thermal oxidation in order to grow a SiO2 insulating layer on the surface, Figure 1a. Thermal oxidation of the wafer was performed at 1150 °C for 70 min, resulting in a 0.6 μm thick oxide layer formed on both sides. The wafer was then coated with a 500 nm thick layer of photoresist (Micro-Chemicals, Ulm, Germany) deposited by spin coating. Photolithography was performed on a double-sided aligner (EVG, St. Florian am Inn, Austria) using a premade mask defining the p+ doping areas. Wet etching of the SiO2 layer was performed using an HF solution diluted with DI water to a concentration of 5%. After the optical lithography step, a thermal diffusion was performed, thus forming two p+ doping regions. Thermal diffusion was performed at 1100 °C for one hour using a boron p-type dopant. Finally, an aluminum layer was deposited by magnetron sputtering on top of the wafer to serve as a metallization for contacts. After one more optical lithography step, the wafer was diced, the chips were placed on TO-type housing, and the contacts were made by wire bonding, as seen in Figure 1a. The layout of the obtained structure is given in Figure 1b. One of the p+ regions was optically occluded by the black resin, which optically isolates the p+-doped region from visible and NIR light, as seen in Figure 1c. In addition, there are two metallic meanders made of sputtered aluminum. These are used to control and measure the temperature at the surface of the device, as seen in Figure 1b–d.

Figure 1.

The structure of the a-p-i-p diode-based light sensor. (a) Fabrication process and cross-section structure. (b) The a-p-i-p layout structure. (c) The layout with black resin deposited. (d) A micrograph of the finished a-p-i-p diode.

The concept of operation is to have both doped regions as p-types, so the device is electrically symmetric and does not rectify strongly—current can flow in either polarity, limited chiefly by carrier injection across the intrinsic slab. Asymmetric illumination provided by optically occluding one of the p+ regions renders photovoltaic-like behavior, a concept not utilized so far. In photovoltaic mode, the device is not externally biased so that photocarriers generated in the i-region are collected mainly by diffusion, not drift, yielding a small voltage and current when illuminated, akin to a solar cell. However, operating without external bias also means that the depletion region is narrower and the carrier collection relies on built-in electric fields and diffusion, potentially resulting in a slower response and lower magnitude signals compared to biased p-i-n structures. By demonstrating that useful transient signals can still be obtained in photovoltaic mode, it was shown that the device can be probed by TCT in order to have a clear picture of high- and low-generating regions.

3. Results

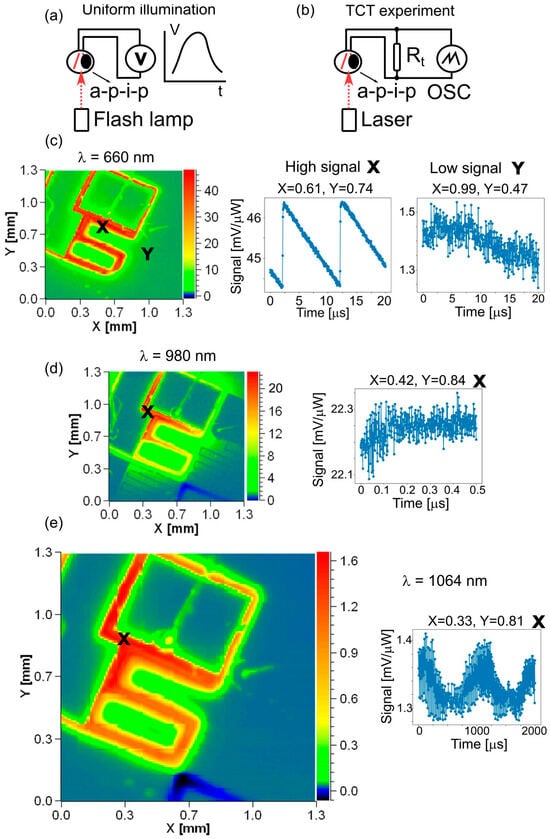

A short qualitative test was performed using a flash lamp to demonstrate that the device produces a photovoltaic signal under uniform illumination, as shown in Figure 2a. This confirms its potential usefulness for a range of applications and justifies further detailed investigation of its operation.

Figure 2.

Results of the TCT scan. (a) The a-p-i-p diode excitation by a uniform light source. (b) TCT set-up schematics. Rt = 1 MΩ. (c) Spatial response of the diode for 660 nm laser light and typical waveforms for the high signal region and low signal region. Rise time of 80 ns; relaxation time of 0.01 ms. Laser power, 3.1 μW. (d) Spatial response map obtained 980 nm laser. (e) 1064 nm laser. Units in the color scale are [mV/μW].

A scanning laser TCT system was used to characterize the spatial response of the device. The system consists of a laser source module, precision optics for beam focusing, motorized translation stages for scanning, and a high-speed data acquisition chain for capturing the transient signals [28]. The laser is delivered via an optical fiber to the focusing optics, which produces a small spot size on the device surface, 8–11 µm in diameter (FWHM). The device under test is mounted on an X–Y stage that can move in programmable increments with high precision (step size of 10 µm). By rastering the stage (or equivalently the laser beam position) in a grid pattern, we obtain a two-dimensional map of the device’s response. The output from the a-p-i-p diode was connected to the oscilloscope with 1 MΩ termination, as seen in Figure 2b.

Three different laser wavelengths were employed for excitation: 660 nm (red visible), 980 nm (NIR), and 1064 nm (NIR just below the silicon bandgap cutoff). These correspond to separate laser diodes or laser sources integrated into the TCT system. Table 1 summarizes the key laser and scanning parameters for the experiments.

Table 1.

Laser scanning TCT parameters and conditions.

The scanned response maps for the a-p-i-p diode device under different illumination wavelengths reveal clear differences in both the magnitude of the transient current and the spatial distribution of sensitivity. As the laser spot is scanned across the exposed sensor surface, a transient current is generated, which appears as warm colors (high signal) in the response maps shown in Figure 2c–e. The characteristic special map and the waveform recorded by the oscilloscope for the laser point light illumination at 660 nm wavelength are given in Figure 2c. The signal will rise sharply (80 ns) as the laser hits the surface and then decline steadily, due to collection and recombination (~0.01 ms). Figure 2c presents a 2D map of the device’s transient signal amplitude (integrated charge) when illuminated with the 660 nm (red) laser, together with the waveforms at two surface points, X and Y. These two points correspond to characteristic regions of high signal (X) and low signal (Y). The high signal shows periodic behavior related to the frequency of the driving laser. Moving from the region of high activity to the region of low activity, the qualitative periodic behavior of the signal stays the same, although the amplitude decreases. In the region of very low activity (Y), only noise is observed, with no characteristic periodic behavior. For the 660 nm laser excitation, the device shows the highest signal compared to the other wavelengths due to near-surface generation of electron–hole pairs. The areas corresponding to the resin-covered meander show no detectable signal and appear indistinguishable from the background noise, while the highest response originates from the p+-doped regions.

For the wavelengths of 980 nm and 1064 nm, silicon’s absorption is quite weak (absorption length on the order of 1 mm), as seen in Figure 2d,e. The output from the TCT scan was scaled depending on the power of the corresponding laser light used for the excitation, as seen in Table 1. The scaling factor for 980 nm was 3.1/4 = 0.775, while for 1064 nm, it was 3.1/100 = 0.031. Despite the low overall response, the highest signal again originates from the p+-doped region, while the intrinsic region produces almost no detectable signal. The waveforms exhibit no discernible periodic behavior, consistent with the low overall signal amplitude and the proximity to the noise floor. The apparent ~1 ms repetition visible in Figure 2e (waveform) does not correspond to any physical or instrumental parameter of the laser illumination. We interpret this feature as an irregular, non-periodic fluctuation—essentially a chaotic component of the transient response—with no identifiable physical meaning. The covered junction under 980 nm and 1064 nm is an interesting case: black resin is actually leaking at this wavelength, so there is a visible negative signal coming from the occluded meander. The overall pattern of the response is qualitatively similar from 980 nm to that of a 1064 nm wavelength. The overall signal is, however, stronger with 980 nm illumination.

4. Discussion

The asymmetric p-i-p silicon diode investigated in this study demonstrates that photovoltaic operation can be achieved in a geometry traditionally regarded as non-photovoltaic. The photovoltaic behavior was demonstrated qualitatively using a simple flash-lamp experiment and examined in greater detail through TCT scans. The experimental results obtained through the Transient Current Technique (TCT) using scanning laser excitation confirm that the asymmetry in optical access, rather than asymmetry in doping or metallization, can drive charge separation and extraction. The observed photocurrent transients under different wavelengths provide a clear indication that the internal field distribution and carrier collection efficiency are strongly influenced by the optical penetration depth and absorption profile of light within the silicon bulk.

The highest transient current amplitude at 660 nm can be attributed to the shallow absorption depth of this wavelength, which confines carrier generation near the illuminated p+ electrode. The resulting built-in potential gradient between the illuminated and obscured electrodes enables efficient charge separation and extraction, leading to pronounced transient signals. In contrast, longer wavelengths (980 nm and 1064 nm) penetrate deeper into the silicon, generating carriers farther from the active junction region. These carriers experience weaker internal fields and higher recombination probabilities, resulting in smaller transient responses. Such wavelength-dependent behavior supports the hypothesis that carrier dynamics in this asymmetric structure are governed by a combination of optical asymmetry and internal field gradients induced by unequal carrier injection and trapping at the two contacts.

From the perspective of previous studies, this finding represents a significant departure from the conventional understanding of silicon photodiodes, which typically rely on p–i–n architectures with vertically aligned junctions and metallization optimized for uniform illumination. Previous reports have emphasized that symmetric p-i-p structures are largely ineffective for photovoltaic operation due to the absence of a built-in electric field. The present work challenges that notion by demonstrating that optical asymmetry alone can induce directional photocurrent flow.

Specific effects, such as the Dember effect [29], may contribute to the signal recorded during TCT scans. While a Dember-type contribution may arise during TCT scans due to the highly localized laser excitation and resulting carrier-concentration gradients, this mechanism cannot operate under uniform illumination. In uniform light, no strong lateral gradients form, and the observed photovoltaic signal instead originates from the device’s inherent a-p-i-p structural asymmetry.

The implications of this study extend beyond the specific p-i-p configuration. It suggests that spatial control of light absorption and surface potential can be harnessed to design photonic and optoelectronic devices that do not rely on conventional junction asymmetry. This could lead to simplified device architectures suitable for integration in flexible or transparent electronics, where traditional doping gradients are difficult to implement. Additionally, the results highlight the potential of the TCT method not only for defect characterization but also for exploring non-equilibrium charge transport phenomena in novel device geometries.

Future research should focus on quantitative modeling of the internal electric field distribution and carrier transport under asymmetric optical excitation. Time-resolved and temperature-dependent measurements could help distinguish between diffusion- and drift-dominated regimes. Moreover, exploring other materials systems (e.g., poly-Si, amorphous Si, or hybrid perovskites) could test the universality of this design principle. Engineering the degree of optical asymmetry—through selective coatings, surface texturing, or wavelength-selective absorbers—may enable tailored spectral responses or self-powered operation under ambient light. Ultimately, the asymmetric p-i-p concept introduces a new paradigm in diode physics, offering a foundation for minimalist photovoltaic and photodetection technologies that operate without the need for conventional junction asymmetry or external bias.

5. Conclusions

The asymmetric p-i-p device, comprising two p+ meandered junctions on n-type silicon (one of which is light-exposed, the other covered), shows a clear wavelength-dependent response when scanned with 660 nm, 980 nm, and 1064 nm laser pulses. Operating in photovoltaic (zero-bias) mode, the device was able to generate measurable transient currents solely from the incident light, showcasing the feasibility of using such structures without external bias (beneficial for reducing dark current and simplifying deployment).

For the first time, it has been demonstrated that a p-i-p device can generate a photocurrent when fabricated in an optically asymmetric configuration. The device shows strong potential for a wide range of applications, including optical pyrometry, laser positioning, X-ray detection, optical communications, photodetection, and optical filtering. It may also find use in imaging systems, optoelectronic sensors, power monitoring of laser sources, and wavelength-selective detection in spectroscopy and environmental sensing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S., J.N.S., G.K. and B.H.; software, G.K., M.S. and B.H.; validation, M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S., J.N.S. and B.H.; resources, K.C., S.D.I. and M.R.R.; data curation, M.S. and B.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, G.K., B.H., J.N.S., K.C., S.D.I. and M.R.R.; visualization, M.S. and B.H.; project administration, M.S. and G.K.; funding acquisition, M.S. and G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been financially supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200026). This work was supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency, project No. PR-12777. The authors gratefully acknowledge partial financial support from the Bilateral project between the Republic of Serbia and the Republic of Slovenia (Contract No. 337-00-110/2023-05/14).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| p-i-p | p-type doped, intrinsic, p-type doped |

| a-p-i-p | Asymmetric p-i-p |

| TCT | Transient Current Technique |

References

- Singh, A.; Singh, S.; Yadav, B.C. In2O3 Nanocubes and ZnWO4 Nanorod-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Self-Powered Humidity Sensors. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2024, 398, 134721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossa, F.; Faga, Y.; Abdou, W.; Ezin, E.C.; Gouton, P. Wireless Sensor Network Deployment: Architecture, Objectives, and Methodologies. Sensors 2025, 25, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Synthesis of High Response Gold/Titanium Dioxide Humidity Sensor and Its Application in Human Respiration. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 30880–30887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, S.D.; Andjelković, M.S.; Duane, R.; Palma, A.J.; Sarajlić, M.; Stanković, S.; Ristić, G.S. Recharging Process of Commercial Floating-Gate MOS Transistor in Dosimetry Application. Microelectron. Reliab. 2021, 126, 114322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Duan, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Tai, H. Observing Mixed Chemical Reactions at the Positive Electrode in the High-Performance Self-Powered Electrochemical Humidity Sensor. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 34158–34170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, M.V.; Sarajlić, M.; Frantlović, M.; Smiljanić, M.M.; Randjelović, D.V.; Zobenica, K.C.; Radović, D.V. Aluminum-Based Self-Powered Hyper-Fast Miniaturized Sensor for Breath Humidity Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 321, 128635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, G.; Sun, J.; Cui, L.; Wang, M. Leakage Monitoring and Diagnosis of LNG Storage Tanks with Temperature Sensing Network Integration and Artificial Intelligence Algorithm. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 055113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, M.C.; Booker, P.; Church, I.; Jones, L.L.; Lipp, J.; Schneider, A.; Seller, P.; Wilson, M.D.; Chsherbakov, I.; Kolesnikova, I.; et al. Characterisation of the HEXITEC 4S X-Ray Spectroscopic Imaging Detector Incorporating through-Silicon via (TSV) Technology. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A: Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2022, 1025, 166083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsch, T.; Huegging, F.; Mackowiak, P.; Zoschke, K.; Rothermund, M.; Owtscharenko, N.; Pohl, D.-L.; Oppermann, H.; Wermes, N. 3D TSV Hybrid Pixel Detector Modules with ATLAS FE-I4 Readout Electronic Chip. J. Inst. 2022, 17, C01029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsenty, A.; Chelly, A. Anomalous Kink Effect in Low-Dimensional Gate-Recessed Fully Depleted SOI MOSFET at Low Temperature. NANO 2015, 10, 1550093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, X. An Analytical Model for Weak Avalanche Induced Kink Effect of PDSOI nMOSFETs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2023, 70, 3430–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennicard, D.; Struth, B.; Hirsemann, H.; Sarajlic, M.; Smoljanin, S.; Zuvic, M.; Lampert, M.O.; Fritzsch, T.; Rothermund, M.; Graafsma, H. A Germanium Hybrid Pixel Detector with 55μm Pixel Size and 65,000 Channels. J. Instrum. 2014, 9, P12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, P.; Defrance, N.; Lesecq, M.; Agboton, A.; Ouhachi, R.; Okada, E.; Gaquiere, C.; De Jaeger, J.-C.; Frayssinet, E.; Cordier, Y. On the Correlation between Kink Effect and Effective Mobility in InAlN/GaN HEMTs. In Proceedings of the 2014 9th European Microwave Integrated Circuit Conference, Rome, Italy, 6–7 October 2014; IEEE: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xiang, Y.; Ma, W.; Fu, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, G. Gold Particles Decorated Reduced Graphene Oxide for Low Level Mercury Vapor Detection with Rapid Response at Room Temperature. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 112995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarajlić, M.; Ramović, R. On the Relationship Between Effective Electron Mobility and Kink Effect for Short-Channel pd Soi Nmos Devices. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2008, 22, 2599–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.K. Complete Guide to Semiconductor Devices, 2nd ed.; IEEE Press: New York, NY, USA; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-471-20240-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jegannathan, G.; Seliuchenko, V.; Dries, T.V.D.; Lapauw, T.; Boulanger, S.; Ingelberts, H.; Kuijk, M. An Overview of CMOS Photodetectors Utilizing Current-Assistance for Swift and Efficient Photo-Carrier Detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, J. Fabrication and Characterization of Low-Temperature Poly-Silicon Lateral p-i-n Diode. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2010, 31, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vobecky, J.; Zahlava, V.; Hazdra, P. High-Power Silicon p-i-n Diode With the Radiation Enhanced Diffusion of Gold. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2014, 35, 375–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, I.; Hayashi, Y.; Yamanaka, M.; Satoh, M. Carrier Separation Effects in Hydrogenated Amorphous Silicon Photoconductors with Multilayer Structures. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 1985, 6, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J. Photoconductive Effect on P-i-p Micro-Heaters Integrated in Silicon Microring Resonators. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geis, M.W.; Spector, S.J.; Grein, M.E.; Yoon, J.U.; Lennon, D.M.; Lyszczarz, T.M. Silicon Waveguide Infrared Photodiodes with >35 GHz Bandwidth and Phototransistors with 50 AW-1 Response. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 5193–5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitsev, A.M.; Burchard, M.; Meijer, J.; Stephan, A.; Burchard, B.; Fahrner, W.R.; Maresch, W. Diamond Pressure and Temperature Sensors for High-Pressure High-Temperature Applications. Phys. Stat. Sol. (a) 2001, 185, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, R.; Denisenko, A.V.; Zaitsev, A.M.; Melnikov, A.A.; Werner, M.; Fahrner, W.R. High Sensitivity Thermal Sensors on Insulating Diamond. Thin Solid Films 1996, 290–291, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisenko, A.; Fahrner, W.R.; Strahle, U.; Henschel, H.; Job, R. Radiation Response of P-i-p Diodes on Diamond Substrates of Various Type: Electrical Properties of Semiconductor-Insulator Homojunctions. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1996, 43, 3081–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tan, C.; Peng, M.; Yu, Y.; Zhong, F.; Wang, P.; He, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, R.; et al. Giant Infrared Bulk Photovoltaic Effect in Tellurene for Broad-Spectrum Neuromodulation. Light. Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhong, F.; Leng, K.; Qiu, M.; Yu, K.; Wang, L.; Rogalski, A.; et al. Spatial Confined Hot Carrier Dynamics for beyond Unity Quantum Efficiency Detection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramberger, G. Advanced TCT Setups. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Workshop on Vertex Detectors—PoS(Vertex2014), Macha Lake, The Czech Republic, 15–19 September 2014; Sissa Medialab: Trieste, Italy, 2015; p. 032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, G.; Hilser, F.; Qiao, W.; Beck, M.; Gebs, R.; Bartels, A.; Huska, K.; Lemmer, U.; Bastian, G.; Johnston, M.; et al. Terahertz emission from lateral photo-Dember currents. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).