Hydration and Barrier Properties of Emulsions with the Addition of Keratin Hydrolysate

Abstract

:1. Introduction

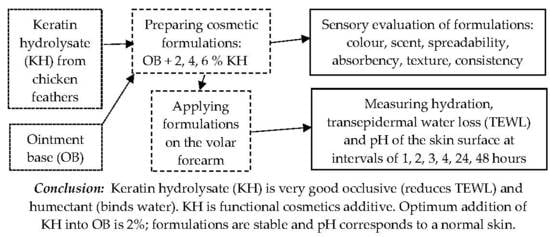

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Keratin Hydrolysate

2.2. Measuring of the Hydration and Barrier Properties of Formulations

2.3. Sensory Evaluation of Formulations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

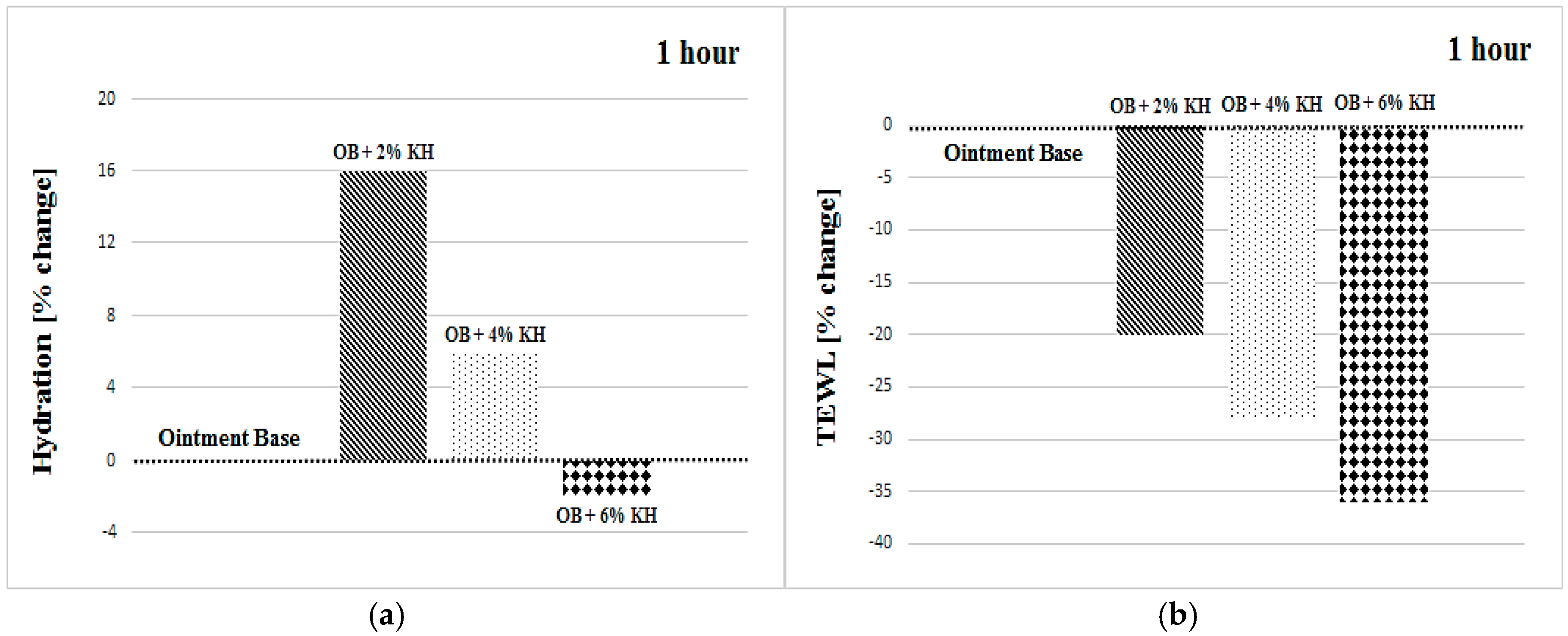

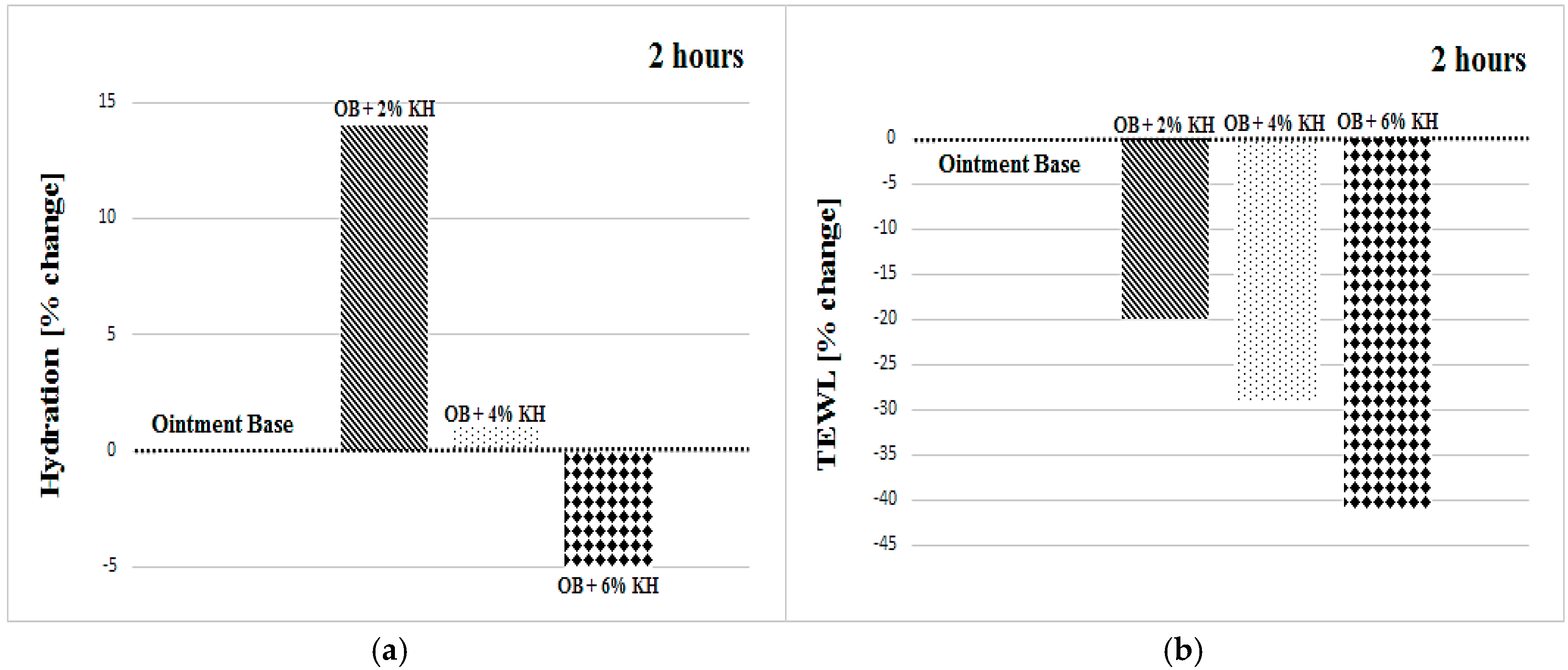

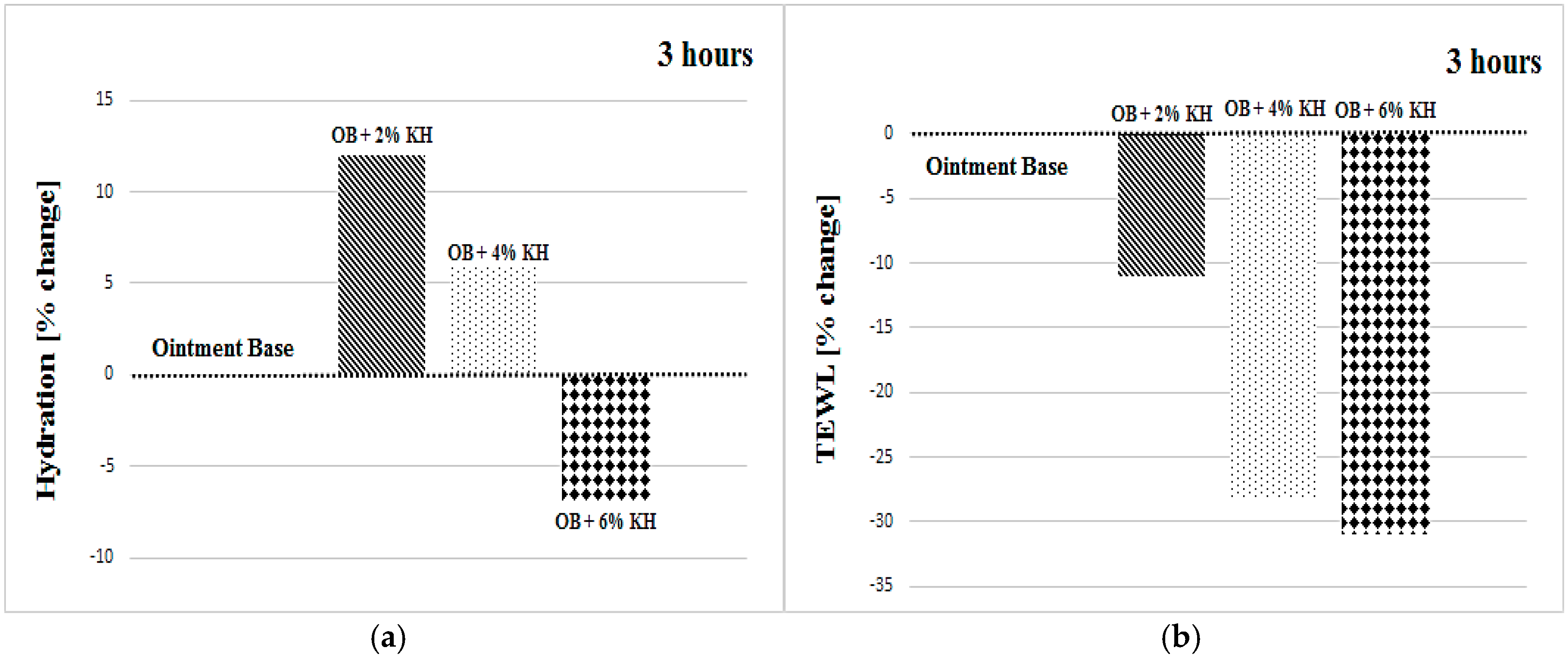

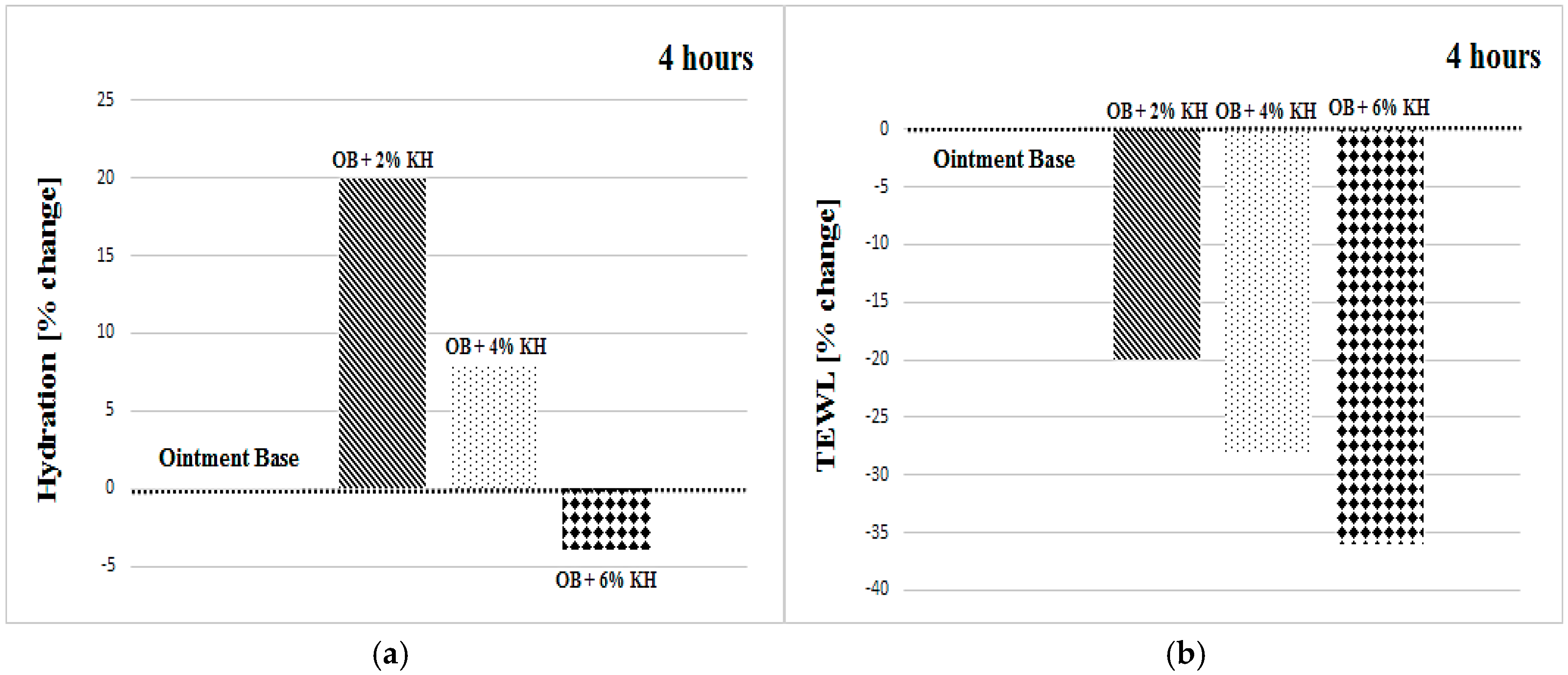

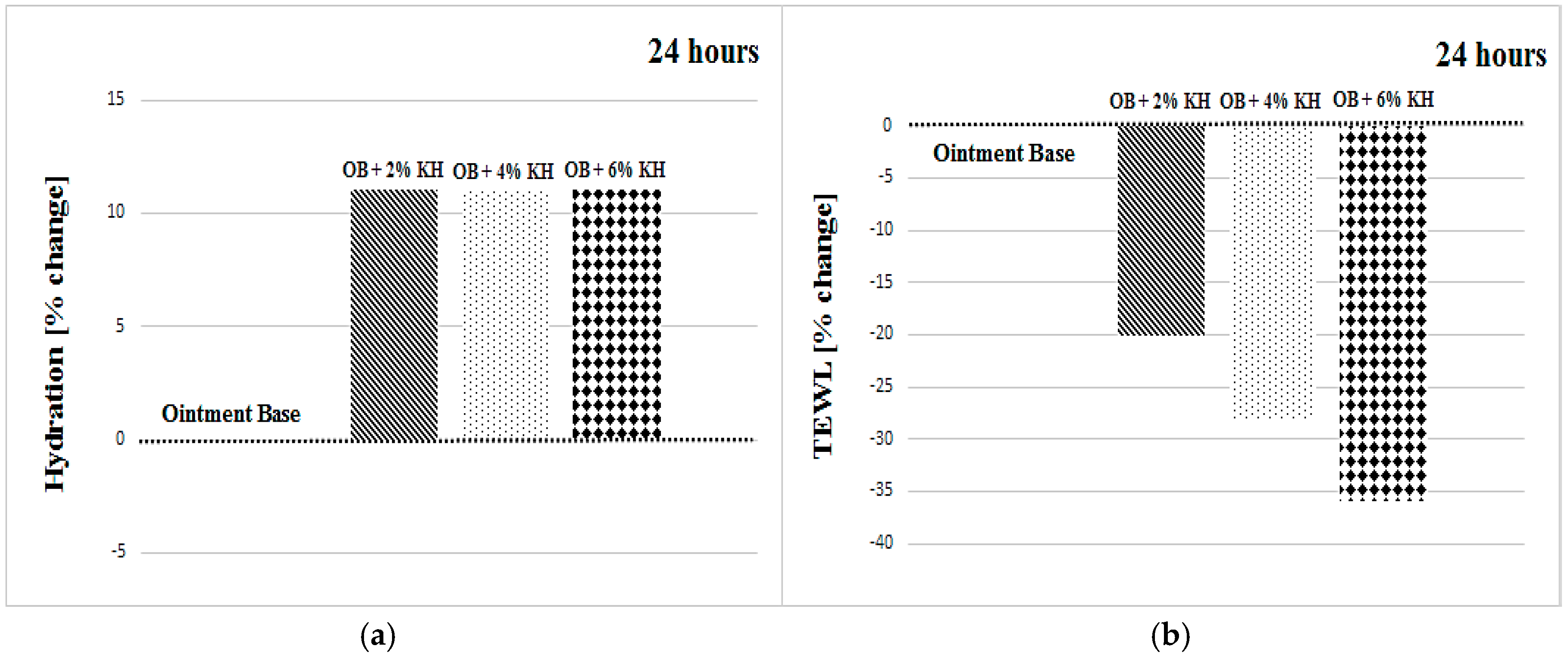

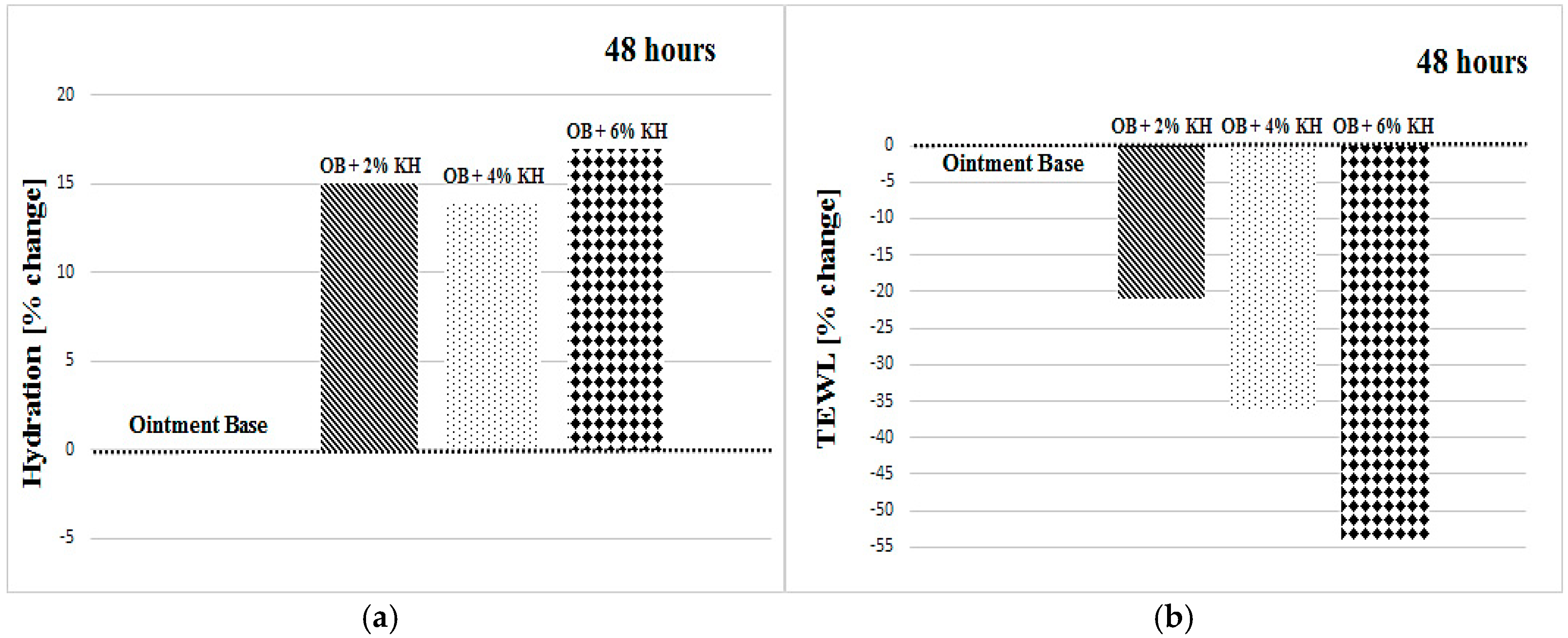

3.1. Hydration

3.2. Transepidermal Water Loss

3.3. pH of the Skin Surface

3.4. Organoleptic Assessments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Draelos, Z.D. Therapeutic moisturizers. Dermatol. Clin. 2000, 18, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier-Sévrain, S.; Bonté, F. Skin hydration: A review on its molecular mechanisms. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2007, 6, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, M.M.; Deem, D.E. Skin moisturizers. II. The effects of cosmetic ingredients on human stratum corneum. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1974, 25, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- International Nomenclature of Cosmetic Ingredients. Available online: http://library.essentialwholesale.com/inci-names-list/ (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Li, G.Y.; Fukunaga, S.; Takenouchi, K.; Nakamura, F. Comparative study of the physiological properties of collagen, gelatin and collagen hydrolysate as cosmetic materials. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2008, 27, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zague, V.; de Freitas, V.; da Costa Rosa, M. Collagen hydrolysate intake increases skin collagen expression and suppresses matrix metalloproteinase 2 activity. J. Med. Food 2011, 14, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.T.; Han, Z.W.; Yu, G.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Cui, R.Y.; Wang, C.B. Inhibitory effect of polypeptide from Chlamys farreri on ultraviolet A-induced oxidative damage on human skin fibroblasts in vitro. Pharmacol. Res. 2004, 49, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, H.; Li, B.; Zhao, X.; Chen, L. The effect of Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus) skin gelatin polypeptides on UV radiationinduced skin photoaging in ICR mice. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Hou, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B. Effects of collagen and collagen hydrolysate from jellyfish (Rhopilema esculentum) on mice skin photoaging induced by UV irradiation. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, H183–H188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, Y.; Shirai, K.; Sato, C. Collagen Incorporating Cosmetics. U.S. Patent 20020150598 A1, 17 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guoying, L.I.; Fukunaga, S.; Takenouchi, K.; Nakamura, F. Physicochemical properties of collagen isolated from calf limed splits. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 2003, 98, 224–229. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, A.W.; Suhimi, N.M.; Abdul Aziz, A.G.K.; Jahim, J.M. Process for production of hydrolysed collagen from agriculture resources: Potential for further development. J. Appl. Sci. 2014, 14, 1319–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, P.; Ling, T.C.; Covington, A.D.; Lyddiatt, A. Enzymatic hydrolysis of bovine hide and recovery of collagen hydrolysate in aqueous two-phase systems. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 89, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Fenske, N.A. Uses of vitamins A, C, and E and related compounds in dermatology: A review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1998, 39, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.L.; Combs, S.B.; Pinnell, S.R. Effects of ascorbic acid on proliferation and collagen synthesis in relation to the donor age of human dermal fibroblasts. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1994, 103, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katiyar, S.K.; Ahmad, N.; Mukhtar, H. Green tea and skin. Arch. Dermatol. 2000, 136, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokrejs, P.; Hrncirik, J.; Janacova, D.; Svoboda, P. Processing of keratin waste of meat industry. Asian J. Chem. 2012, 24, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar]

- Mokrejs, P.; Svoboda, P.; Hrncirik, J.; Janacova, D.; Vasek, V. Processing poultry feathers into keratin hydrolysate through alkaline-enzymatic hydrolysis. Waste Manag. Res. 2011, 29, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokrejs, P.; Krejci, O.; Svoboda, P. Producing keratin hydrolysates from sheep wool. Orient. J. Chem. 2011, 27, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Mokrejs, P.; Krejci, O.; Svoboda, P.; Vasek, V. Modeling technological conditions for breakdown of waste sheep wool. Rasayan J. Chem. 2011, 4, 728–735. [Google Scholar]

- Polaskova, J.; Pavlackova, J.; Vltavska, P. Moisturizing effect of topical cosmetic products applied to dry skin. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 64, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Polaskova, J.; Pavlackova, J.; Egner, P. Effect of vehicle on the performance of active moisturizing substances. Skin Res. Technol. 2015, 21, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.R.P.; Martelli, S.M.; Gandolfo, C. Influence of the glycerol concentration on some physical properties of feather keratin films. Food Hydrocoll. 2006, 20, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, S. Films based on human hair keratin as substrates for cell culture and tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6854–6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, T.; Okitsu, N.; Tachibana, A.; Yamauchi, K. Preparation and characterization of keratin–chitosan composite film. Biomaterials 2009, 23, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, T.; Okitsu, N.; Tachibana, A.; Yamauchi, K. Fabrication and characterization of chemically crosslinked keratin films. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2004, 24, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Shibayama, M.; Tanabe, T.; Yamauchi, K. Preparation and physicochemical properties of compression-molded keratin films. Biomaterials 2009, 25, 2265–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrejs, P.; Hutta, M.; Pavlackova, J.; Egner, P.; Benicek, L. The cosmetic and dermatological potential of keratin hydrolysate. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2017, 16, e21–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects; Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- ISO 6658. Sensory Analysis—Methodology—General Guidance; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8586. Sensory Analysis—General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Selected Assessors and Expert Sensory Assessors; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8587. Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Ranking; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, K.P.; Cua, A.B.; Maibach, K.I. Skin aging. Effect on transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, skin surface pH, and casual sebum content. Arch. Dermatol. 1991, 127, 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, A.; Schiavi, M.E.; Seidenari, S. Capacitance, transepidermal water loss and causal level of sebum in healthy subjects in relation to site, sex and age. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1995, 17, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Information and Operating Instructions for the Multi Probe Adapter MPA and Its Probe; Courage and Khazaka electronic GmbH: Köln, Germany, 2013.

| Time (h) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 24 | 48 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydration (% change vs. Ointment base) ± SD | ||||||

| OB + 2% KH | +16 ± 15 | +14 ± 16 | +12 ± 9 | +19 ± 14 | +11 ± 18 | +15 ± 9 |

| OB + 4% KH | +6 ± 19 | +1 ± 18 | +5 ± 10 | +7 ± 16 | +11 ± 9 | +14 ± 15 |

| OB + 6% KH | −3 ± 25 | −4 ± 14 | −7 ± 18 | −4 ± 17 | +11 ± 14 | +17 ± 14 |

| TEWL (% change vs. Ointment base) ± SD | ||||||

| OB + 2% KH | −20 ± 15 | −20 ± 22 | −11 ± 21 | −20 ± 21 | −23 ± 20 | −21 ± 17 |

| OB + 4% KH | −28 ± 12 | −29 ± 20 | −28 ± 20 | −28 ± 24 | −28 ± 20 | −36 ± 20 |

| OB + 6% KH | −36 ± 16 | −41 ± 21 | −31 ± 17 | −36 ± 17 | −36 ± 20 | −54 ± 17 |

| pH | ||||||

| Ointment base (OB) | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 0.6 |

| OB + 2% KH | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.6 |

| OB + 4% KH | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.5 |

| OB + 6% KH | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.6 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mokrejš, P.; Pavlačková, J.; Janáčová, D.; Huťťa, M. Hydration and Barrier Properties of Emulsions with the Addition of Keratin Hydrolysate. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5040064

Mokrejš P, Pavlačková J, Janáčová D, Huťťa M. Hydration and Barrier Properties of Emulsions with the Addition of Keratin Hydrolysate. Cosmetics. 2018; 5(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleMokrejš, Pavel, Jana Pavlačková, Dagmar Janáčová, and Matouš Huťťa. 2018. "Hydration and Barrier Properties of Emulsions with the Addition of Keratin Hydrolysate" Cosmetics 5, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5040064

APA StyleMokrejš, P., Pavlačková, J., Janáčová, D., & Huťťa, M. (2018). Hydration and Barrier Properties of Emulsions with the Addition of Keratin Hydrolysate. Cosmetics, 5(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5040064