Preparation and Properties of Plasma Etching-Resistant Y2O3 Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Films Deposition

2.2. Etching

2.3. Films Characterizations

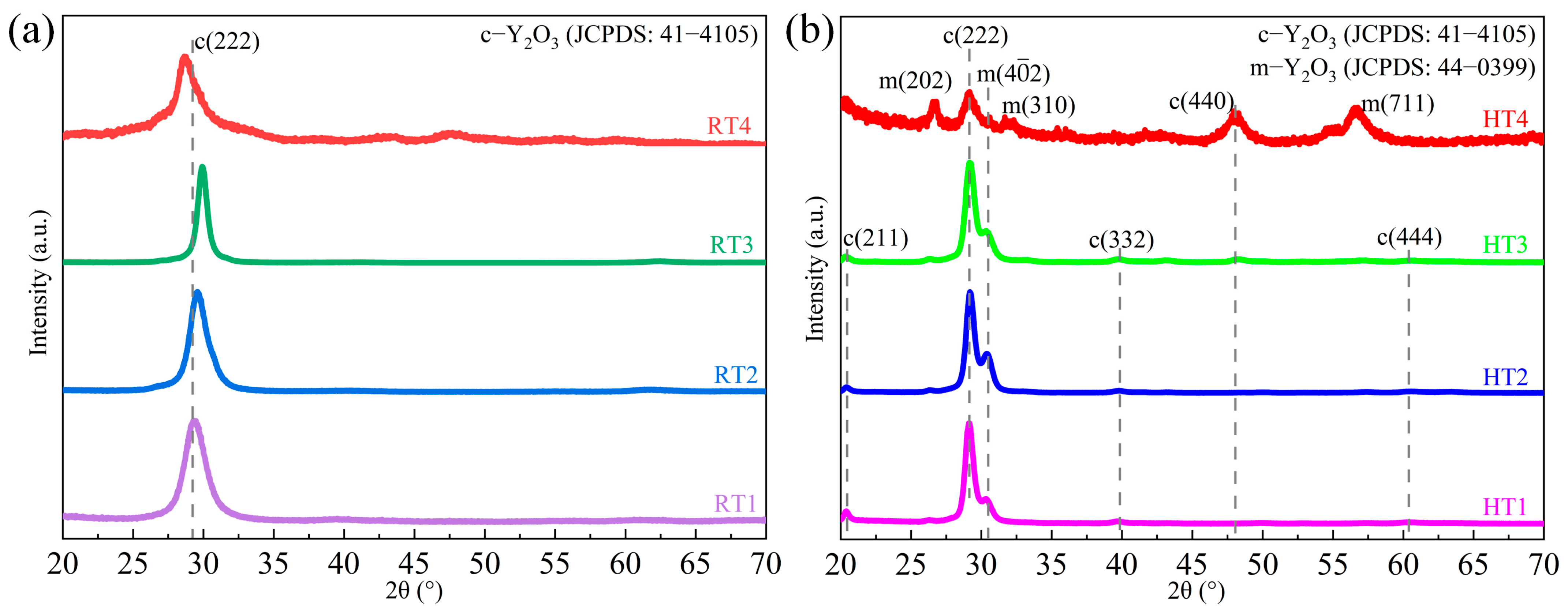

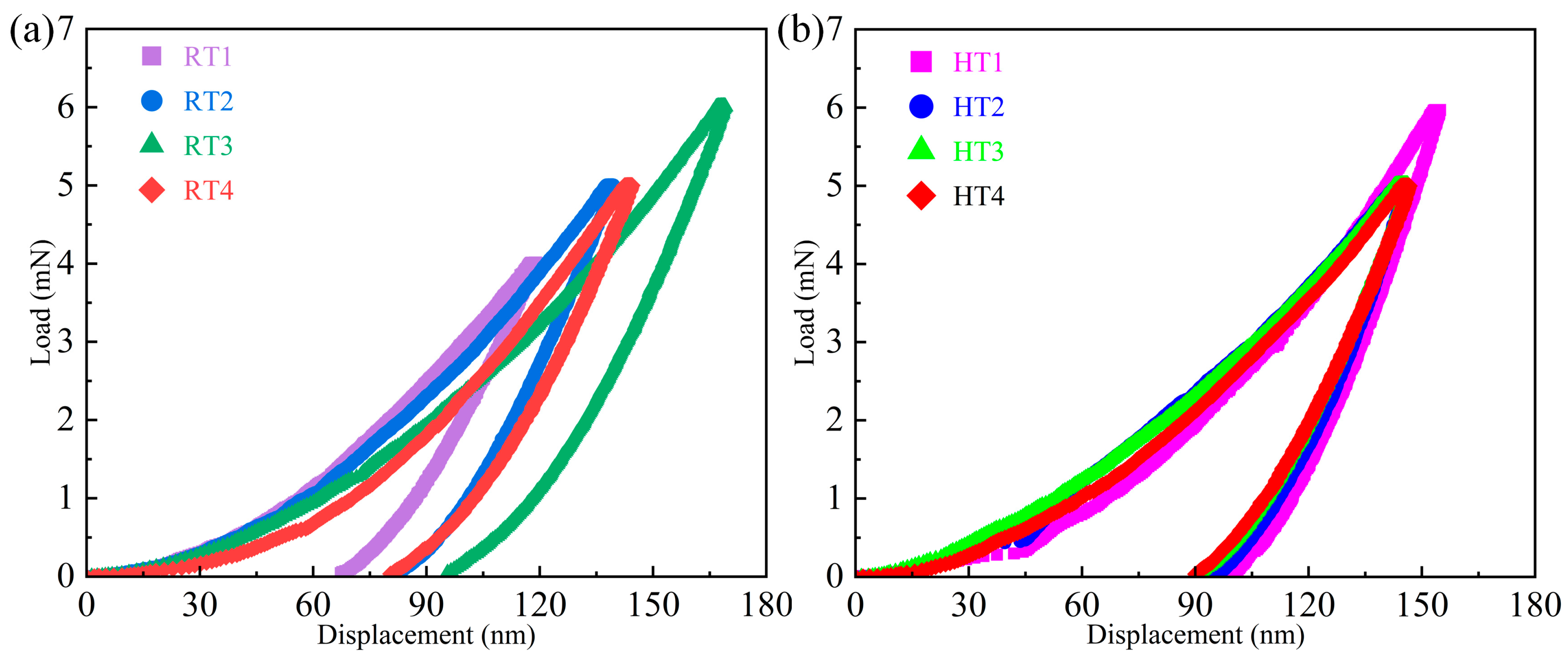

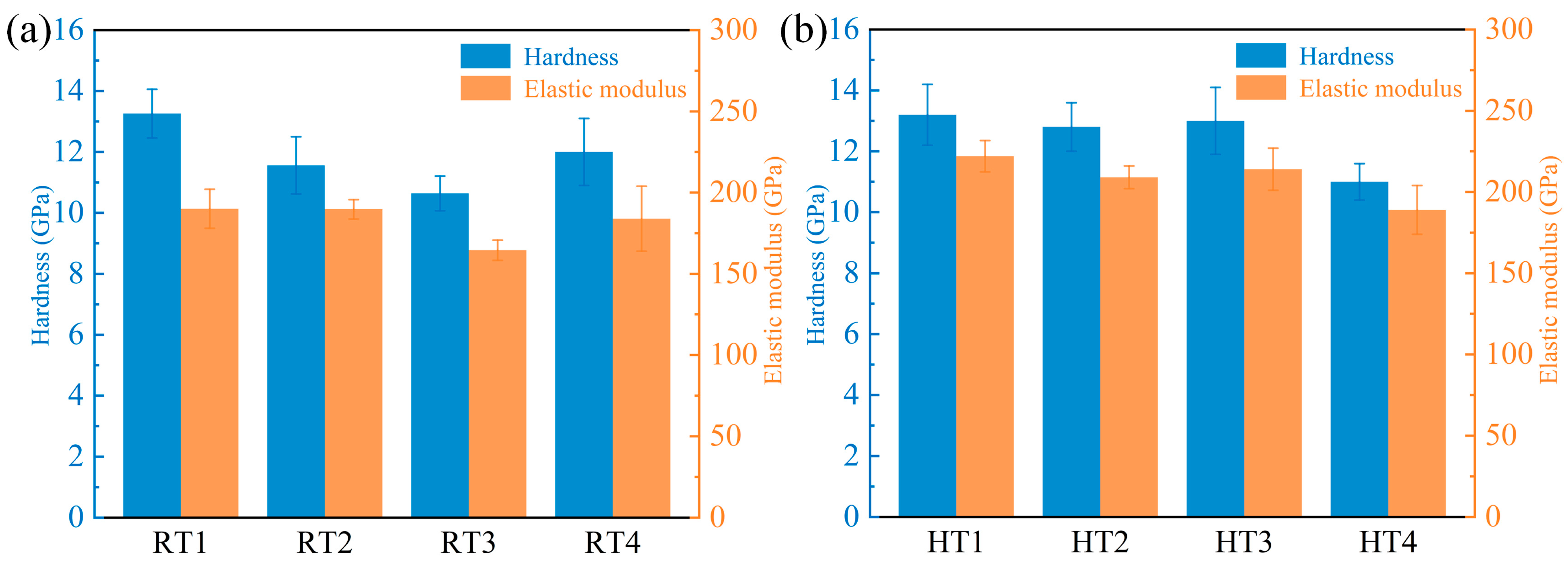

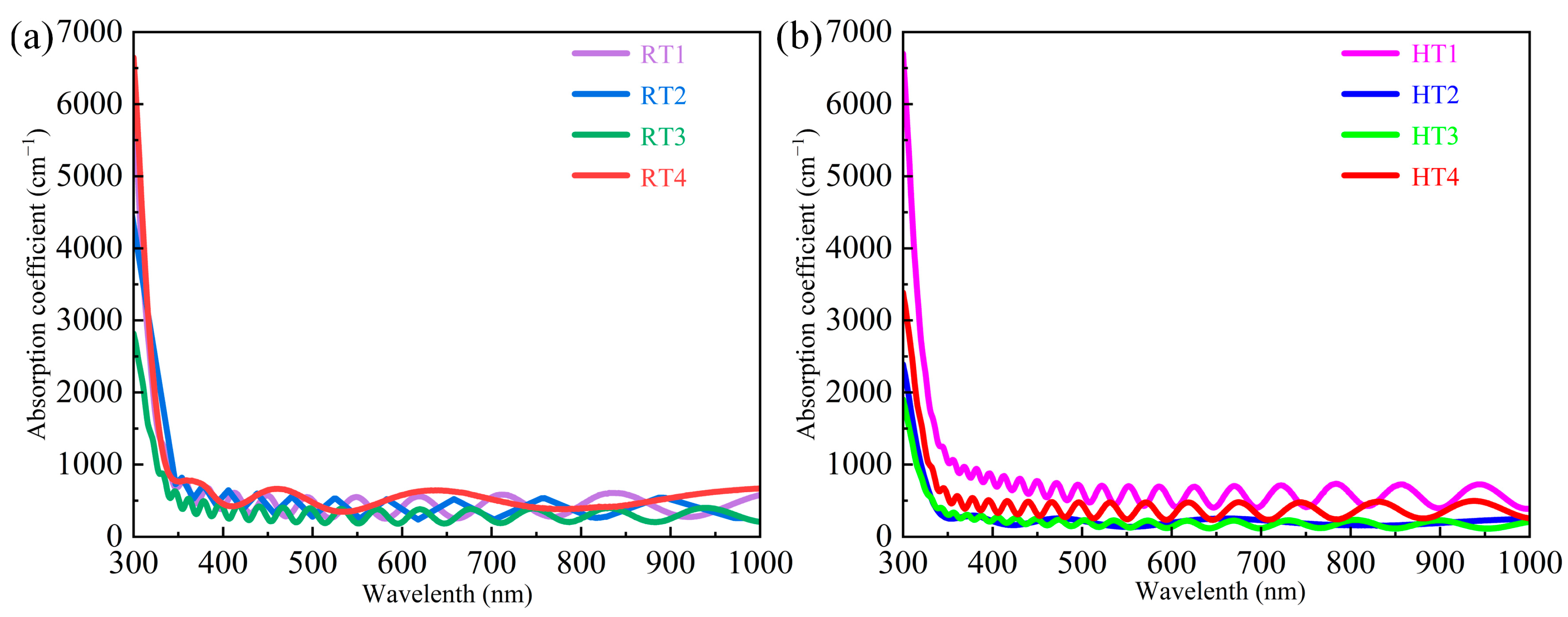

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Response Hysteresis Curve

3.2. Morphology and Microstructure

3.3. Mechanical Properties

3.4. Optical Properties

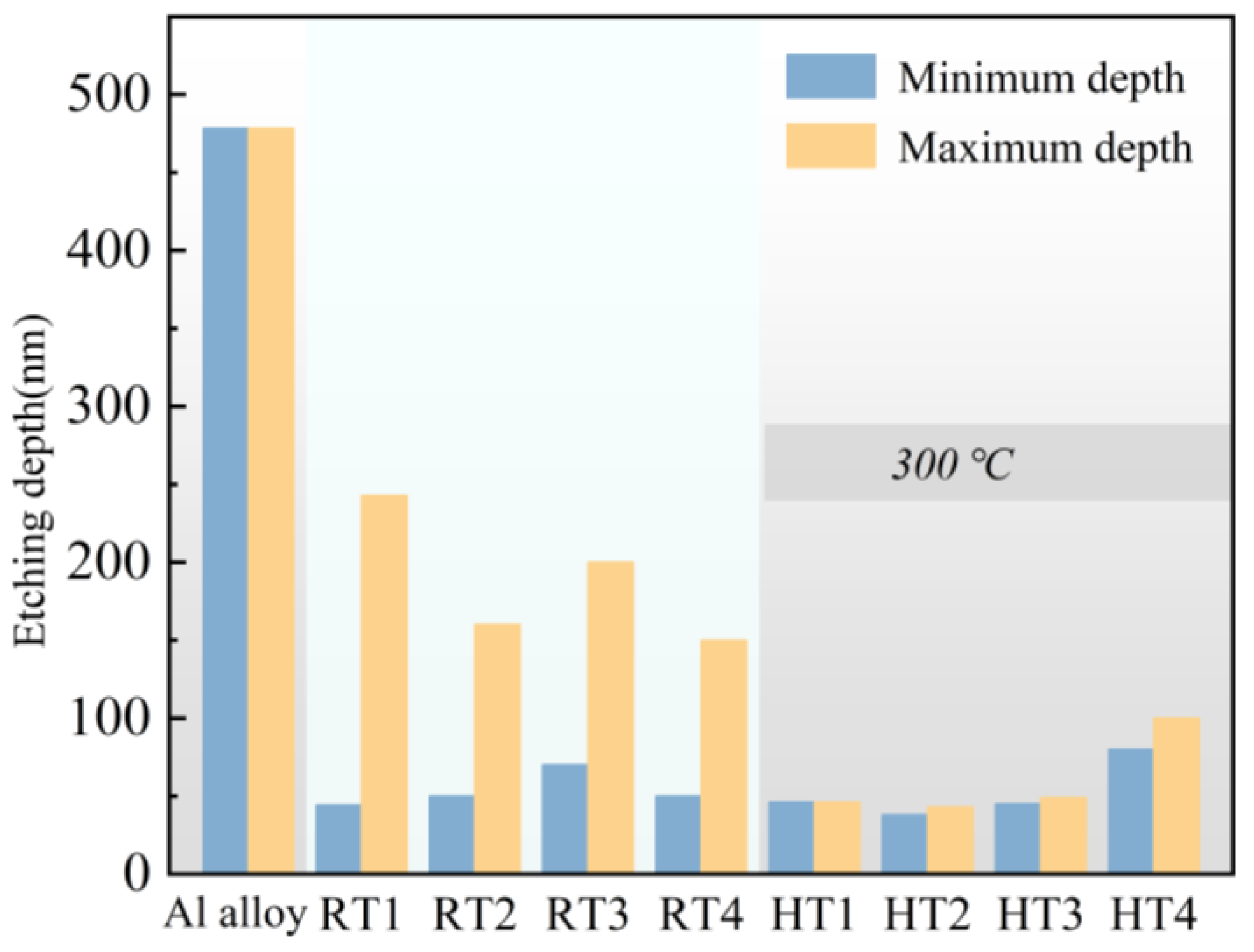

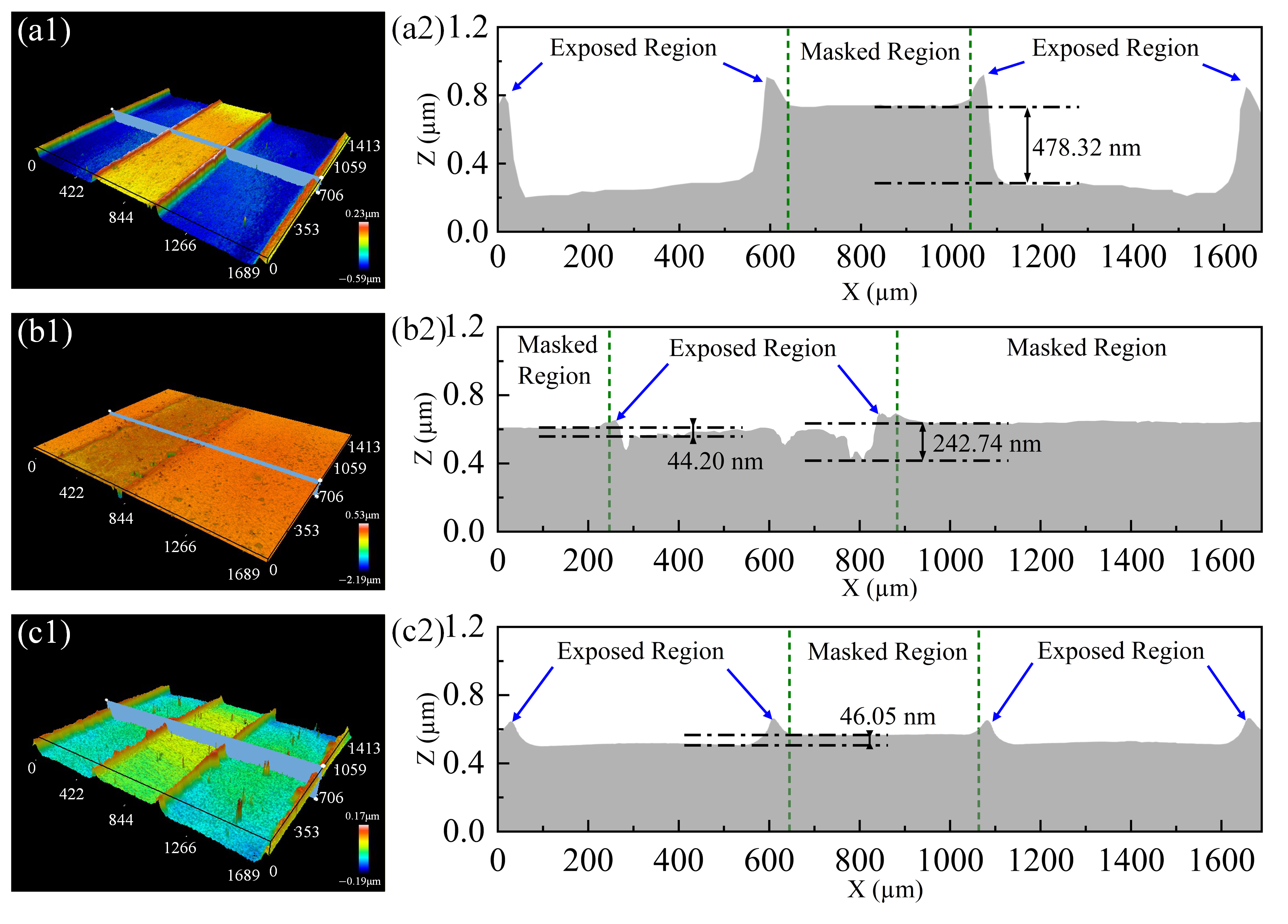

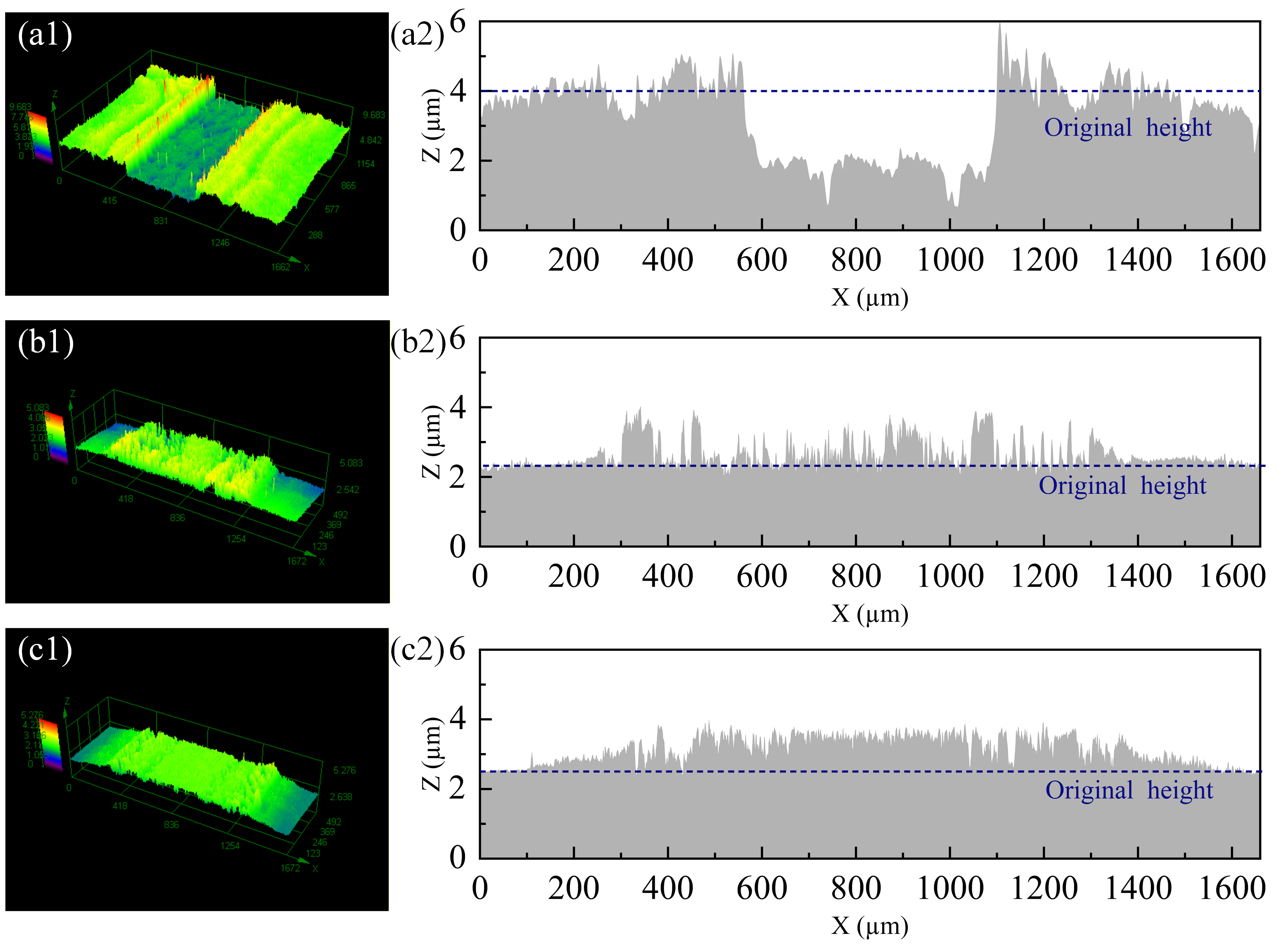

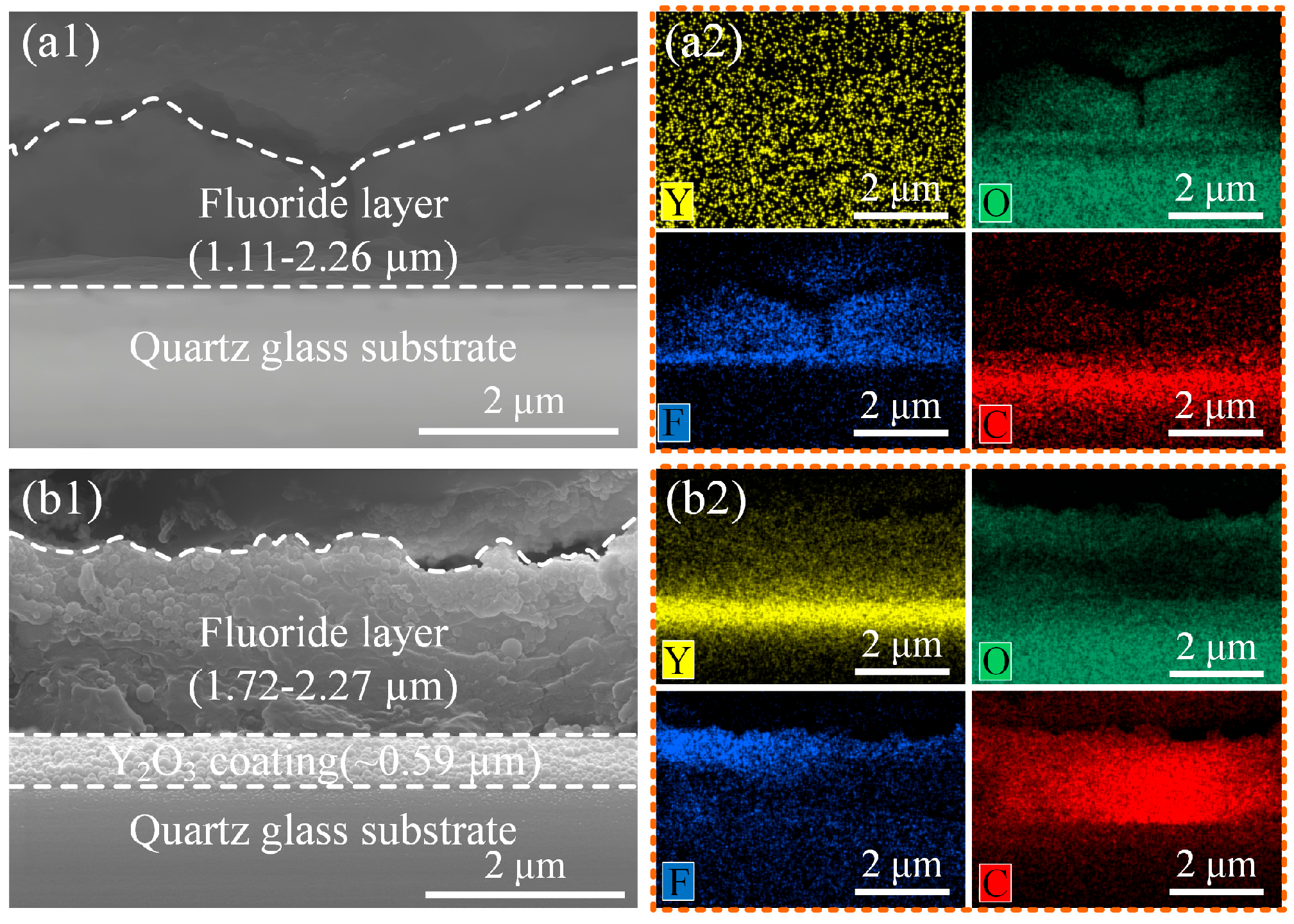

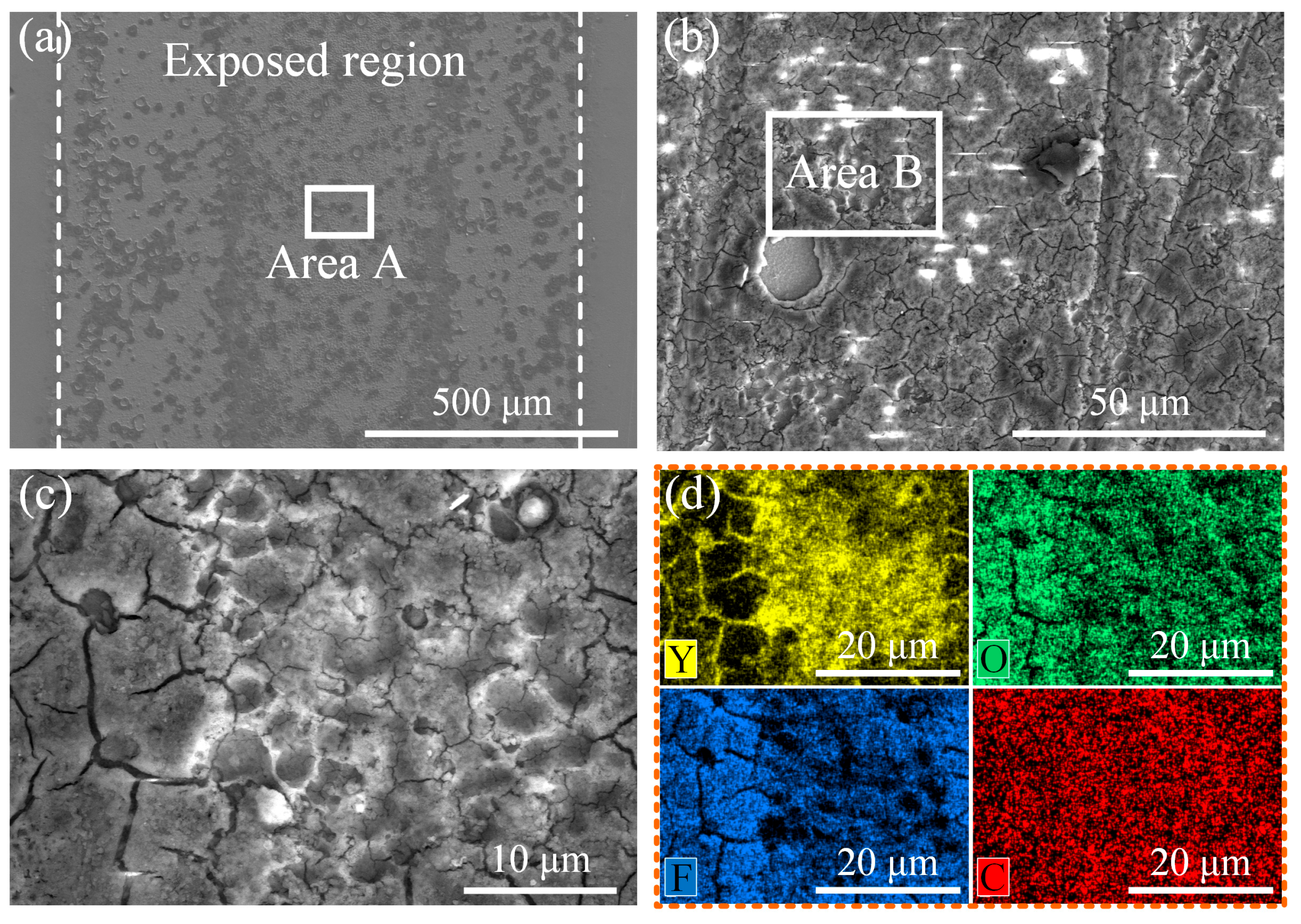

3.5. Plasma Etching Resistant

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choi, J.H.; Im, W.B.; Kim, H.-J. Plasma resistant glass (PRG) for reducing particulate contamination during plasma etching in semiconductor manufacturing: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, L. Etching: The art of semiconductor micromachining. Micromachines 2025, 16, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moothedath, A.; Ren, Z. Enhanced plasma etching using nonlinear parameter evolution. Micro Nano Eng. 2024, 25, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, T.; Nakayama, H.; Nagaike, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Shimada, M.; Okuyama, K. Particle reduction and control in plasma etching equipment. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2005, 18, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.-B.; Jang, H.-S.; Oh, Y.-S.; Lee, I.-H.; Lee, S.-M. Effects of HfO2 addition on the plasma resistance of Y2O3 thin films deposited by e-beam PVD. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 640, 158359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindelmann, M.; Stamminger, M.; Schön, N.; Rasinski, M.; Eichel, R.-A.; Hausen, F.; Bram, M.; Guillon, O. Erosion behavior of Y2O3 in fluorine-based etching plasmas: Orientation dependency and reaction layer formation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 104, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-Y.; Raju, K.; Lee, H.-K. Formation of YOF on Y2O3 through surface modification with NH4F and its plasma-resistance behavior. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 47513–47518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Huang, L.; Gong, C.; Yu, Y. Erosion resistance of Y2O3 ceramics in CF4 etching plasma: Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 669, 160509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.-C.; Zhao, L.; Luo, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, B.-P.; Yokota, H.; Ito, Y.; Li, J.-F. Plasma etching behavior of Y2O3 ceramics: Comparative study with Al2O3. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 366, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, J.; Kim, M.; Kwon, H.; Maeng, S.; Choi, E.; Chung, C.-W.; Yun, J.-Y. Investigation of contamination particles generation and surface chemical reactions on Al2O3, Y2O3, and YF3 coatings in F-based plasma. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 629, 157367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.J.; Park, Y.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, H.-N.; Ko, J.-W.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, H.-C. Physiochemical etching characteristics and surface analysis of Y2O3-MgO nanocomposite under different CF4/Ar/O2 plasma atmospheres. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 641, 158483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-Y.; Oh, Y.-S.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.-M. High erosion resistant Y2O3–carbon electroconductive composite under the fluorocarbon plasma. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-S.; Bae, K.-B.; Min, S.-R.; Oh, Y.-S.; Lee, I.-H.; Lee, S.-M. Remarkably enhanced plasma resistance of Y2O3- and Y-rich thin films through controllable reactive sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 685, 162050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, B.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Ji, L.; Wang, A.; Sun, C.; Li, H. Effect of O2/Ar ratio on the microstructure and tribological properties of Y2O3 films by multi-arc ion plating. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 43032–43043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Choi, E.; Lee, D.; Seo, J.; Back, T.-S.; So, J.; Yun, J.-Y.; Suh, S.-M. The effect of powder particle size on the corrosion behavior of atmospheric plasma spray-Y2O3 coating: Unraveling the corrosion mechanism by fluorine-based plasma. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 606, 154958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier-Kiener, V.; Korte-Kerzel, S. Advanced nanoindentation testing: Beyond the Oliver–Pharr method. MRS Bull. 2025, 50, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strijckmans, K.; Schelfhout, R.; Depla, D. Tutorial: Hysteresis during the reactive magnetron sputtering process. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 241101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emmerik, C.I.; Hendriks, W.A.P.M.; Stok, M.M.; de Goede, M.; Chang, L.; Dijkstra, M.; Segerink, F.B.; Post, D.; Keim, E.G.; Dikkers, M.J.; et al. Relative oxidation state of the target as guideline for depositing optical quality RF reactive magnetron sputtered Al2O3 layers. Opt. Mater. Express 2020, 10, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugurov, A.R.; Kuzminov, E.D.; Panin, A.V. The effect of substrate bias on the structure, mechanical and tribological properties of DC magnetron sputtered Ti-Al-Ta-Si-N coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 517, 132858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yan, K.; Gao, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, Q. Microstructure and mechanical properties of CuZr thin-film metallic glasses deposited by magnetron sputtering. Lubricants 2025, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCPDS 41-1105; Yttrium Oxide (Y2O3), Cubic. International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD): Newtown Square, PA, USA, 1999.

- Taghavi Pourian Azar, G.; Er, D.; Ürgen, M. The role of superimposing pulse bias voltage on DC bias on the macroparticle attachment and structure of TiAlN coatings produced with CA-PVD. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 350, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Alishahi, M.; Souček, P.; Buršíková, V.; Zábranský, L.; Gröner, L.; Burmeister, F.; Blug, B.; Daum, P.; Mikšová, R.; et al. Effect of substrate bias voltage on the composition, microstructure and mechanical properties of W-B-C coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 528, 146966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusli, N.A.; Muhammad, R.; Ghoshal, S.K.; Nur, H.; Nayan, N.; Jaafar, S.N. Bias voltage dependent structure and morphology evolution of magnetron sputtered YSZ thin film: A basic insight. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCPDS 44-0399; Yttrium Oxide (Y2O3), Monoclinic. International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD): Newtown Square, PA, USA, 1999.

- Lei, P.; Dai, B.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Han, J. Controllable phase formation and physical properties of yttrium oxide films governed by substrate heating and bias voltage. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 8921–8930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.H.; Ko, D.H.; Jeong, K.; Whangbo, S.W.; Whang, C.N.; Choi, S.C.; Cho, S.J. Structural transition of crystalline Y2O3 film on Si(111) with substrate temperature. Thin Solid Film. 1999, 349, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaboriaud, R.J.; Paumier, F.; Jublot, M.; Lacroix, B. Ion irradiation-induced phase transformation mechanisms in Y2O3 thin films. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2013, 311, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, T.; Jin, X.; Ma, W.; Li, H.; Fan, L.; Hong, Y.; Wang, S. In situ XPS analysis of surface transformations in activated Ti-Zr-V thin films by nitrogen venting. Vacuum 2025, 234, 114089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, D.P.; Baburin, A.S.; Lotkov, E.S.; Rodionov, I.A.; Baryshev, A.V. In-situ ellipsometric study of WO3–x dielectric permittivity during gasochromic colouration. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 82, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Liang, W.; Miao, Q.; Depla, D. The effect of energy and momentum transfer during magnetron sputter deposition of yttrium oxide thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, E.J.; Atuchin, V.V.; Kruchinin, V.N.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Ramana, C.V. Electronic structure and optical quality of nanocrystalline Y2O3 film surfaces and interfaces on silicon. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 13644–13651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, L. Impurity element analysis of aluminum hydride using PIXE, XPS and elemental analyzer technique. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2021, 488, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyss, O.; Breuer, U.; Zander, D. An in-depth investigation of the native oxide formed on Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys by XPS, XRR and ToF-SIMS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 687, 162258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, L.; Kim, K.H. Fabrication and properties of hard coatings by a hybrid PVD method. Lubricants 2025, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liang, D.; Dai, W.; Wang, Q.; Yan, J.; Wang, J. Mechanical properties and high-temperature steam oxidation of Cr/CrN multi-layers produced by high-power impulse magnetron sputtering. Coatings 2025, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zeng, J.; Chen, D.; Luo, F.; Wang, Q.; Dai, W.; Zhang, R. Comparison of corrosion behavior of a-C coatings deposited by cathode vacuum arc and filter cathode vacuum arc techniques. Coatings 2024, 14, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, T.S. The influence of Y2O3 ceramic rare-earth oxide nanoparticles on the bandgap energy and refractive index of polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 25408–25415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktorczyk, T.; Biegański, P.; Serafińczuk, J. Optical properties of nanocrystalline Y2O3 thin films grown on quartz substrates by electron beam deposition. Opt. Mater. 2016, 59, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatsepin, A.; Kuznetsova, Y.; Zatsepin, D.; Wong, C.-H.; Law, W.-C.; Tang, C.-Y.; Gavrilov, N. Exciton luminescence and optical properties of nanocrystalline cubic Y2O3 films prepared by reactive magnetron sputtering. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, M.; Gherendi, F.; Dobrin, D.; Perrière, J. From transparent to black amorphous zinc oxide thin films through oxygen deficiency control. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 225705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitanov, V.; Kolaklieva, L.; Kakanakov, R.; Cholakova, T.; Pashinski, C.; Kolchev, S.; Zlatareva, E.; Atanasova, G.; Tsanev, A.; Hingerl, K. Investigation of optical properties of complex Cr-Based hard coatings deposited through unbalanced magnetron sputtering intended for real industrial applications. Coatings 2024, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, T.A.; Alanazi, S.S.; El-Nasser, K.S.; Alshammari, A.H.; Ismael, A. Structure–property relationships in PVDF/SrTiO3/CNT nanocomposites for optoelectronic and solar cell applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Song, L.; You, L.; Zhao, L. Incorporation effect of Y2O3 on the structure and optical properties of HfO2 thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 271, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreethi, R.; Hwang, Y.-J.; Lee, H.-Y.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, K.-A. Stability and plasma etching behavior of yttrium-based coatings by air plasma spray process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 454, 129182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, H.; Lee, C. The importance of intimate inter-crystallite bonding for the plasma erosion resistance of vacuum kinetic sprayed Y2O3 coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 374, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-K.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Huang, S.-Y. Passivation effect on the surface characteristics and corrosion properties of yttrium oxide films undergoing SF6 plasma treatment. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 19824–19830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-B.; Kim, J.-T.; Oh, S.-G.; Yun, J.-Y. Contamination particles and plasma etching behavior of atmospheric plasma sprayed Y2O3 and YF3 coatings under NF3 Plasma. Coatings 2019, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kwon, H.; Park, H.; Lee, C. Correlation of plasma erosion resistance and the microstructure of YF3 coatings prepared by vacuum kinetic spray. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2020, 29, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control Voltage (V) | O2 (Sccm) | Temperature (°C) | Bias (V) | Time (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT1 | −300 | 0~5 | 25 | 0 | 60 |

| RT2 | −300 | 0~5 | 25 | −200 | 60 |

| RT3 | −300 | 0~5 | 25 | −400 | 60 |

| RT4 | −250 | 0~5 | 25 | −200 | 120 |

| HT1 | −300 | 0~5 | 300 | 0 | 60 |

| HT2 | −300 | 0~5 | 300 | 0 | 120 |

| HT3 | −300 | 0~5 | 300 | 0 | 180 |

| HT4 | −250 | 0~5 | 300 | 0 | 120 |

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Etching | Chemical Etching | |

| Ionization power (W) | 1500 | 1200 |

| Bias power (W) | 400 | 200 |

| Bias voltage (V) | −200 | −100 |

| Gas | Ar | Ar, CF4 |

| Gas flow rate (sccm) | 150 | 10, 50 |

| Chamber pressure (Pa) | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Etching time (min) | 40 | 60 |

| Elemental Content (at.%) | O/Y | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Y | O | ||

| RT1 | 42.45 | 57.55 | 1.36 |

| HT1 | 41.13 | 58.87 | 1.43 |

| RT1 | RT2 | RT3 | RT4 | HT1 | HT2 | HT3 | HT4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average transmittance (%) | 83.33 | 84.88 | 85.88 | 85.55 | 82.20 | 87.14 | 82.36 | 86.32 |

| Average absorption coefficient α (cm−1) | 426.17 | 374.98 | 299.16 | 511.15 | 581.23 | 197.74 | 177.90 | 368.59 |

| Optical band gap energy Eg (eV) | 3.94 | 3.56 | 3.84 | 3.91 | 3.89 | 3.90 | 3.88 | 3.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, K.; Gao, Z.; Dai, W.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q. Preparation and Properties of Plasma Etching-Resistant Y2O3 Films. Coatings 2025, 15, 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121397

Zhang R, Peng J, Zhang X, Guo K, Gao Z, Dai W, Wu Z, Xu Y, Wang Q. Preparation and Properties of Plasma Etching-Resistant Y2O3 Films. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121397

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Rui, Jiaxing Peng, Xiaobo Zhang, Kesheng Guo, Zecui Gao, Wei Dai, Zhengtao Wu, Yuxiang Xu, and Qimin Wang. 2025. "Preparation and Properties of Plasma Etching-Resistant Y2O3 Films" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121397

APA StyleZhang, R., Peng, J., Zhang, X., Guo, K., Gao, Z., Dai, W., Wu, Z., Xu, Y., & Wang, Q. (2025). Preparation and Properties of Plasma Etching-Resistant Y2O3 Films. Coatings, 15(12), 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121397