Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Phosphorylated Tau-217 Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease Using Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor (CNT-FET) Biosensor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

2.2. Fabrication of CNT-FET Device

2.3. Functionalization of CNT-FET Biosensors

2.4. Far-UV CD Spectra Measurements

2.5. Electrical and Sensing Measurements

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

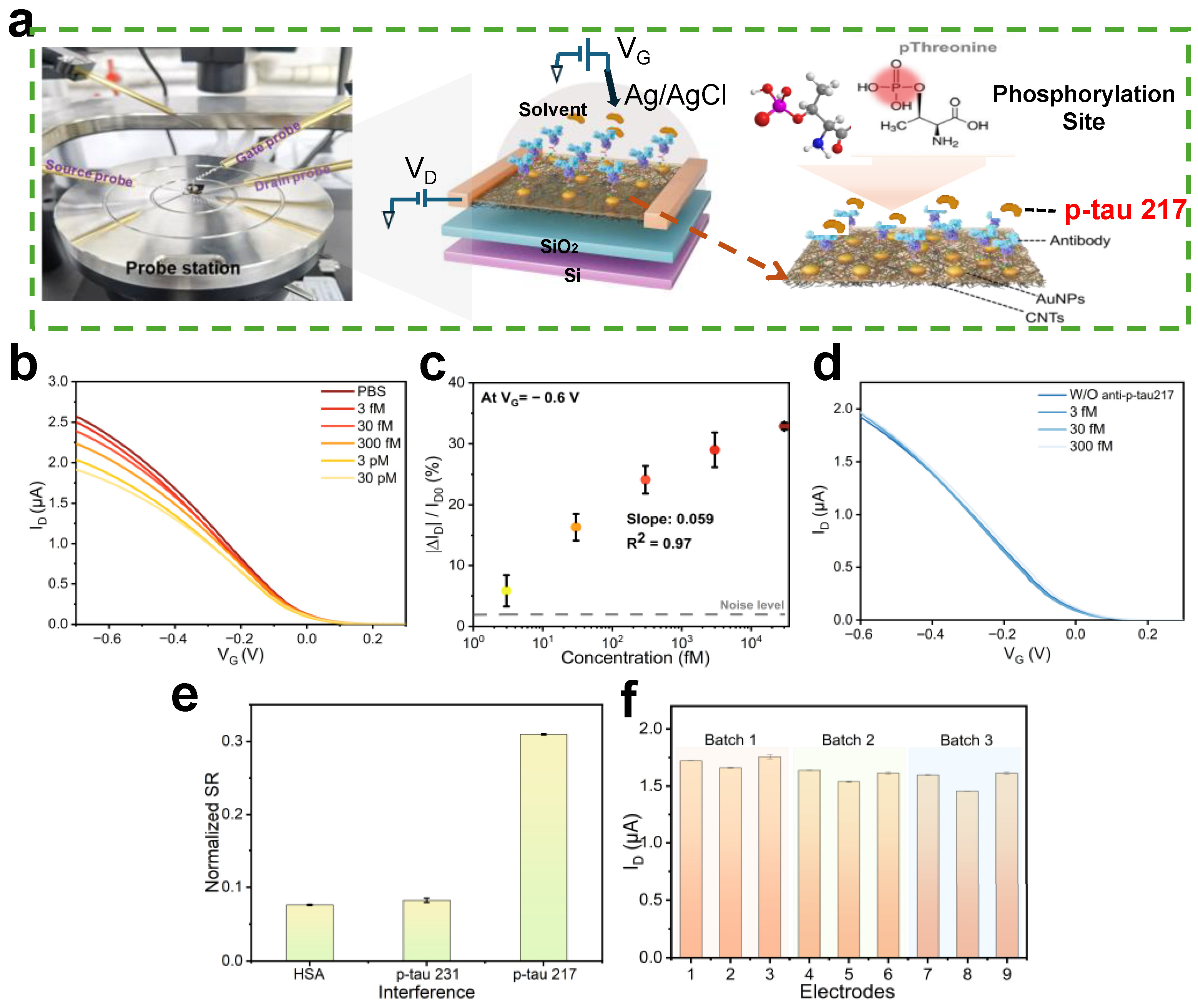

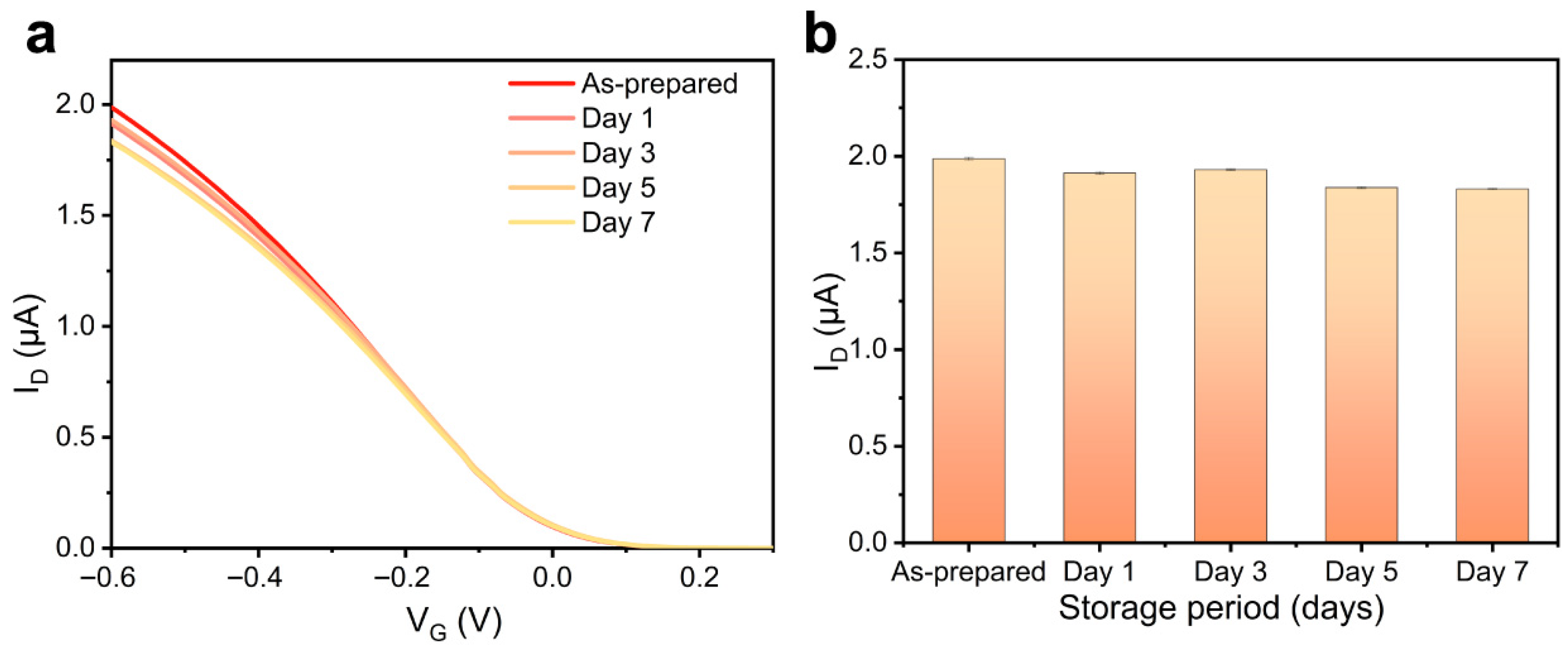

3.1. Characterization and Fabrication of CNT-FET Biosensors

3.2. Antibody Immobilization

3.3. Secondary Structural Stability Characterization of p-tau217 Peptides

3.4. Performance Verification of CNT-FET Immunosensor

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seshadri, S.; Wolf, P.A. Lifetime risk of stroke and dementia: Current concepts, and estimates from the Framingham Study. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 459–480. [CrossRef]

- Parnetti, L.; Chipi, E.; Salvadori, N.; D’Andrea, K.; Eusebi, P. Prevalence and risk of progression of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease stages: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, A. The Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Spectrum: Diagnosis and Management. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 103, 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teipel, S.; Gustafson, D.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Hansson, O.; Babiloni, C.; Wagner, M.; Riedel-Heller, S.; Kilimann, I.; Tang, Y. Alzheimer’s disease—Standard of diagnosis, treatment, care, and prevention. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, L.; Kay, G.; Kong Thoo Lin, P. Current and emerging therapeutic targets of alzheimer’s disease for the design of multi-target directed ligands. Medchemcomm 2019, 10, 2052–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Barve, K.; Kumar, M. Recent Advancements in Pathogenesis, Diagnostics and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D.S.K.; Tse, H.Y.J.; Wong, D.W.; Chan, C.Y.; Wan, W.L.; Chu, K.K.; Lau, S.W.; Lo, L.L.; Wong, T.Y.; So, Y.K.; et al. The Effects of Exergaming on the Depressive Symptoms of People With Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2025, 34, 1648–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, E.S.W.; Cheung, D.S.K.; Chiu, A.T.S.; Cheung, J.C.W.; Wong, D.W.C. A Drum-Based Serious Game for Physical and Cognitive Training in Older Adults: Development and Mixed Methods Usability Study. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, D.P.; Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Shadrin, A.A.; Bahrami, S.; Holland, D.; Rongve, A.; Børte, S.; Winsvold, B.S.; Drange, O.K.; et al. A genome-wide association study with 1,126,563 individuals identifies new risk loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1276–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, O.; Edelmayer, R.; Boxer, A.; Carrillo, M.; Mielke, M.; Rabinovici, G.; Salloway, S.; Sperling, R.; Zetterberg, H.; Teunissen, C. The Alzheimer’s Association appropriate use recommendations for blood biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 2669–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.J.; Ribaldi, F.; Lathuiliere, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Janelidze, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Scheffler, M.; Assal, F.; Garibotto, V.; Blennow, K.; et al. Head-to-head study of diagnostic accuracy of plasma and cerebrospinal fluid p-tau217 versus p-tau181 and p-tau231 in a memory clinic cohort. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 2053–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuzy, A.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Palmqvist, S.; Janelidze, S.; Dage, J.; Hansson, O. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 14, e14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhauria, M.; Mondal, R.; Deb, S.; Shome, G.; Chowdhury, D.; Sarkar, S.; Benito-León, J. Blood-Based Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease: Advancing Non-Invasive Diagnostics and Prognostics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélemy, N.R.; Horie, K.; Sato, C.; Bateman, R.J. Blood plasma phosphorylated-tau isoforms track CNS change in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20200861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikari, T.K.; Ashton, N.J.; Brinkmalm, G.; Brum, W.S.; Benedet, A.L.; Montoliu-Gaya, L.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Pascoal, T.A.; Suárez-Calvet, M.; Rosa-Neto, P.; et al. Blood phospho-tau in Alzheimer disease: Analysis, interpretation, and clinical utility. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelidze, S.; Stomrud, E.; Smith, R.; Palmqvist, S.; Mattsson, N.; Airey, D.C.; Proctor, N.K.; Chai, X.; Shcherbinin, S.; Sims, J.R.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid p-tau217 performs better than p-tau181 as a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélemy, N.R.; Li, Y.; Joseph-Mathurin, N.; Gordon, B.A.; Hassenstab, J.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Buckles, V.; Fagan, A.M.; Perrin, R.J.; Goate, A.M.; et al. A soluble phosphorylated tau signature links tau, amyloid and the evolution of stages of dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milà-Alomà, M.; Ashton, N.J.; Shekari, M.; Salvadó, G.; Ortiz-Romero, P.; Montoliu-Gaya, L.; Benedet, A.L.; Karikari, T.K.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Vanmechelen, E.; et al. Plasma p-tau231 and p-tau217 as state markers of amyloid-β pathology in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1797–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesseling, H.; Mair, W.; Kumar, M.; Schlaffner, C.N.; Tang, S.; Beerepoot, P.; Fatou, B.; Guise, A.J.; Cheng, L.; Takeda, S.; et al. Tau PTM Profiles Identify Patient Heterogeneity and Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2020, 183, 1699–1713.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarto, J.; Esteller-Gauxax, D.; Guillén, N.; Falgàs, N.; Borrego-Écija, S.; Massons, M.; Fernández-Villullas, G.; González, Y.; Tort-Merino, A.; Bosch, B.; et al. Accuracy and clinical applicability of plasma tau 181 and 217 for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis in a memory clinic cohort. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Calvet, M.; Karikari, T.K.; Ashton, N.J.; Lantero Rodríguez, J.; Milà-Alomà, M.; Gispert, J.D.; Salvadó, G.; Minguillon, C.; Fauria, K.; Shekari, M.; et al. Novel tau biomarkers phosphorylated at T181, T217 or T231 rise in the initial stages of the preclinical Alzheimer’s continuum when only subtle changes in Aβ pathology are detected. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossenkoppele, R.; van der Kant, R.; Hansson, O. Tau biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: Towards implementation in clinical practice and trials. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.; Janelidze, S.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Binette, A.; Strandberg, O.; Brum, W.; Karikari, T.; González-Ortiz, F.; Di Molfetta, G.; Meda, F.; et al. Differential roles of Aβ42/40, p-tau231 and p-tau217 for Alzheimer’s trial selection and disease monitoring. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Baiardi, S.; Ladogana, A.; Zenesini, C.; Bartoletti-Stella, A.; Poleggi, A.; Mammana, A.; Polischi, B.; Pocchiari, M.; Capellari, S.; et al. Comparison between plasma and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for the early diagnosis and association with survival in prion disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahim, P.; Zetterberg, H.; Simrén, J.; Ashton, N.J.; Norato, G.; Schöll, M.; Tegner, Y.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Blennow, K. Association of Plasma Biomarker Levels With Their CSF Concentration and the Number and Severity of Concussions in Professional Athletes. Neurology 2022, 99, e347–e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Ortiz, F.; Kac, P.; Brum, W.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Karikari, T. Plasma phospho-tau in Alzheimer’s disease: Towards diagnostic and therapeutic trial applications. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therriault, J.; Servaes, S.; Tissot, C.; Rahmouni, N.; Ashton, N.; Benedet, A.; Karikari, T.; Macedo, A.; Lussier, F.; Stevenson, J.; et al. Equivalence of plasma p-tau217 with cerebrospinal fluid in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 4967–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Poljak, A.; Valenzuela, M.; Mayeux, R.; Smythe, G.A.; Sachdev, P.S. Meta-analysis of plasma amyloid-β levels in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011, 26, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Park, S.; Park, C.B. Clinically accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease via multiplexed sensing of core biomarkers in human plasma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teunissen, C.; Kolster, R.; Triana-Baltzer, G.; Janelidze, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Kolb, H. Plasma p-tau immunoassays in clinical research for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 21, e14397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.; Wen, X.; Wang, Y.; Tan, R.; Li, H.; Tu, Y. Development of a P-tau217 Electrochemiluminescent Immunosensor Reinforced with Au-Cu Nanoparticles for Alzheimer’s Disease Precaution. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 4176–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.G.; Choi, S.H.; Cho, S. Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarker Detection Using Field Effect Transistor-Based Biosensor. Biosensors 2023, 13, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, D.; Lee, D.; Yoon, D.; Hwang, K. Multiplexed femtomolar detection of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in biofluids using a reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 167, 112505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciou, S.-H.; Hsieh, A.-H.; Lin, Y.-X.; Sei, J.-L.; Govindasamy, M.; Kuo, C.-F.; Huang, C.-H. Sensitive label-free detection of the biomarker phosphorylated tau-217 protein in Alzheimer’s disease using a graphene-based solution-gated field effect transistor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 228, 115174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalafi, M.; Dartora, W.J.; McIntire, L.B.J.; Butler, T.A.; Wartchow, K.M.; Hojjati, S.H.; Razlighi, Q.R.; Shirbandi, K.; Zhou, L.; Chen, K.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of phosphorylated tau217 in detecting Alzheimer’s disease pathology among cognitively impaired and unimpaired: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Yoo, G.; Chang, Y.; Kim, H.; Jose, J.; Kim, E.; Pyun, J.; Yoo, K. A carbon nanotube metal semiconductor field effect transistor-based biosensor for detection of amyloid-beta in human serum. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 50, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, M.; Dai, C.; Chen, R.; Yang, L.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, D.; et al. Ultrasensitive Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antibody by Graphene Field-Effect Transistors. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 7897–7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Han, L.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Song, W.; Xu, C.; Cai, X.; et al. Sensitivity-Enhancing Strategies of Graphene Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors for Biomarker Detection. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 2705–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.-A.; Yao, K.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Wong, D.S.; Wong, D.W.; Cheung, J.C. The Versatility of Biological Field-Effect Transistor-Based Biosensors (BioFETs) in Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Applications and Future Directions for Peritoneal Dialysis Monitoring. Biosensors 2025, 15, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzer, A.M.; Michael, Z.P.; Star, A. Carbon Nanotubes for the Label-Free Detection of Biomarkers. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 7448–7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, G.; Lau, C.; Wright, A.; Fuller, S.; Bishop, M.D.; Srimani, T.; Kanhaiya, P.; Ho, R.; Amer, A.; Stein, Y.; et al. Modern microprocessor built from complementary carbon nanotube transistors. Nature 2019, 572, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Xiao, M.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. Aptamer-Functionalized Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors for Alzheimer’s Disease Serum Biomarker Detection. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Li, H.; Zhao, W.; Song, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, L. Overcoming Debye screening effect in field-effect transistors for enhanced biomarker detection sensitivity. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 20864–20884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabsi, S.; Ahmed, A.; Dennis, J.; Khir, M.; Algamili, A. A Review of Carbon Nanotubes Field Effect-Based Biosensors. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 69509–69521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ni, W.; Jin, D.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, M.M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, G.J. Nanosensor-Driven Detection of Neuron-Derived Exosomal Aβ(42) with Graphene Electrolyte-Gated Transistor for Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 5719–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, X.; Wei, T.; Wang, K.; Zhao, Z.; Cao, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor Biosensor with an Enlarged Gate Area for Ultra-Sensitive Detection of a Lung Cancer Biomarker. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 27299–27306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, W.; Hu, Y.; Cui, Y. Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor-Based Chemical and Biological Sensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, M.M.; Ni, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.J. Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor Biosensor for Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Breast Cancer Exosomal miRNA21. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 15501–15507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xiao, M.; Wu, D.; Lin, Y.; Liu, L.; He, J.; Zhang, G.; Peng, L.-M.; Zhang, Z. Wafer-Scale Uniform Carbon Nanotube Transistors for Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Disease Biomarkers. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 8866–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xiao, M.; Xie, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, G.; Wei, N.; et al. Amplification-Free Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Down to Single Virus Level by Portable Carbon Nanotube Biosensors. Small 2023, 19, e2208198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Luo, F.; Qiu, B.; Lin, Z.; Chen, H. Electrochemiluminescence Biosensor for Hyaluronidase Based on the Adjustable Electrostatic Interaction between the Surface-Charge-Controllable Nanoparticles and Negatively Charged Electrode. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 2012–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, R.P.; de Souza, J.P.; Blankschtein, D.; Bazant, M.Z. Theory of Surface Forces in Multivalent Electrolytes. Langmuir 2019, 35, 11550–11565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, Y.; Rangadurai, A.K.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Kay, L.E. Mapping the per-residue surface electrostatic potential of CAPRIN1 along its phase-separation trajectory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2210492119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsström, B.; Axnäs, B.B.; Rockberg, J.; Danielsson, H.; Bohlin, A.; Uhlen, M. Dissecting antibodies with regards to linear and conformational epitopes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, L.; Qiao, X.; Qi, F.; Nishida, N.; Hoshino, T. Analysis of Binding Modes of Antigen-Antibody Complexes by Molecular Mechanics Calculation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 2396–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, G.; Li, T.; Zhu, T.; Xi, G. Identification of the linear immunodominant epitopes in the β subunit of β-conglycinin and preparation of epitope antibodies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shan, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, L. Prediction and characterization of the linear IgE epitopes for the major soybean allergen β-conglycinin using immunoinformatics tools. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 56, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, A.; Mejias-Gomez, O.; Pedersen, L.; Morth, P.; Kristensen, P.; Jenkins, T.; Goletz, S. Structural trends in antibody-antigen binding interfaces: A computational analysis of 1833 experimentally determined 3D structures. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 23, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.n.; Denzler, L.; Hood, O.; Martin, A. Do antibody CDR loops change conformation upon binding? mAbs 2024, 16, 2322533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limorenko, G.; Lashuel, H.A. Revisiting the grammar of Tau aggregation and pathology formation: How new insights from brain pathology are shaping how we study and target Tauopathies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 513–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Kant, R.; Bauer, J.; Karow-Zwick, A.; Kube, S.; Garidel, P.; Blech, M.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J. Adaption of human antibody λ and κ light chain architectures to CDR repertoires. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2019, 32, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Yao, K.; Li, J.; Wong, D.W.-C.; Cheung, J.C.-W. Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Phosphorylated Tau-217 Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease Using Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor (CNT-FET) Biosensor. Biosensors 2025, 15, 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120784

Wang J, Yao K, Li J, Wong DW-C, Cheung JC-W. Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Phosphorylated Tau-217 Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease Using Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor (CNT-FET) Biosensor. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):784. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120784

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiao, Keyu Yao, Jiahua Li, Duo Wai-Chi Wong, and James Chung-Wai Cheung. 2025. "Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Phosphorylated Tau-217 Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease Using Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor (CNT-FET) Biosensor" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120784

APA StyleWang, J., Yao, K., Li, J., Wong, D. W.-C., & Cheung, J. C.-W. (2025). Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Phosphorylated Tau-217 Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease Using Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor (CNT-FET) Biosensor. Biosensors, 15(12), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120784