Comparison of Mid and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy to Predict Creatinine, Urea and Albumin in Serum Samples as Biomarkers of Renal Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Samples Preparation

2.2. MIR Spectroscopy

2.3. NIR Spectroscopy

2.4. Spectra Pre-Processing and Processing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of Serum Samples Simulating Kidney Disease

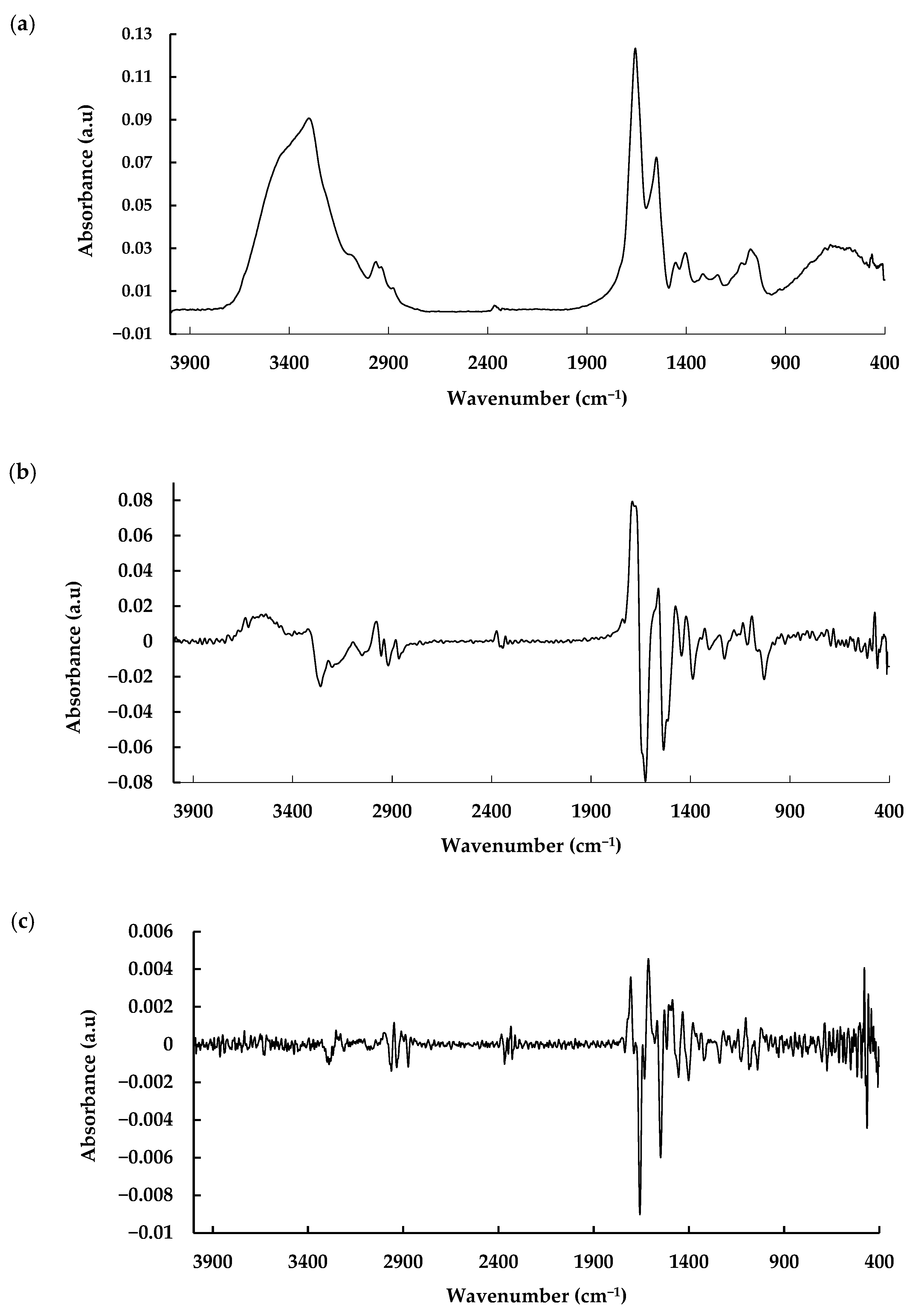

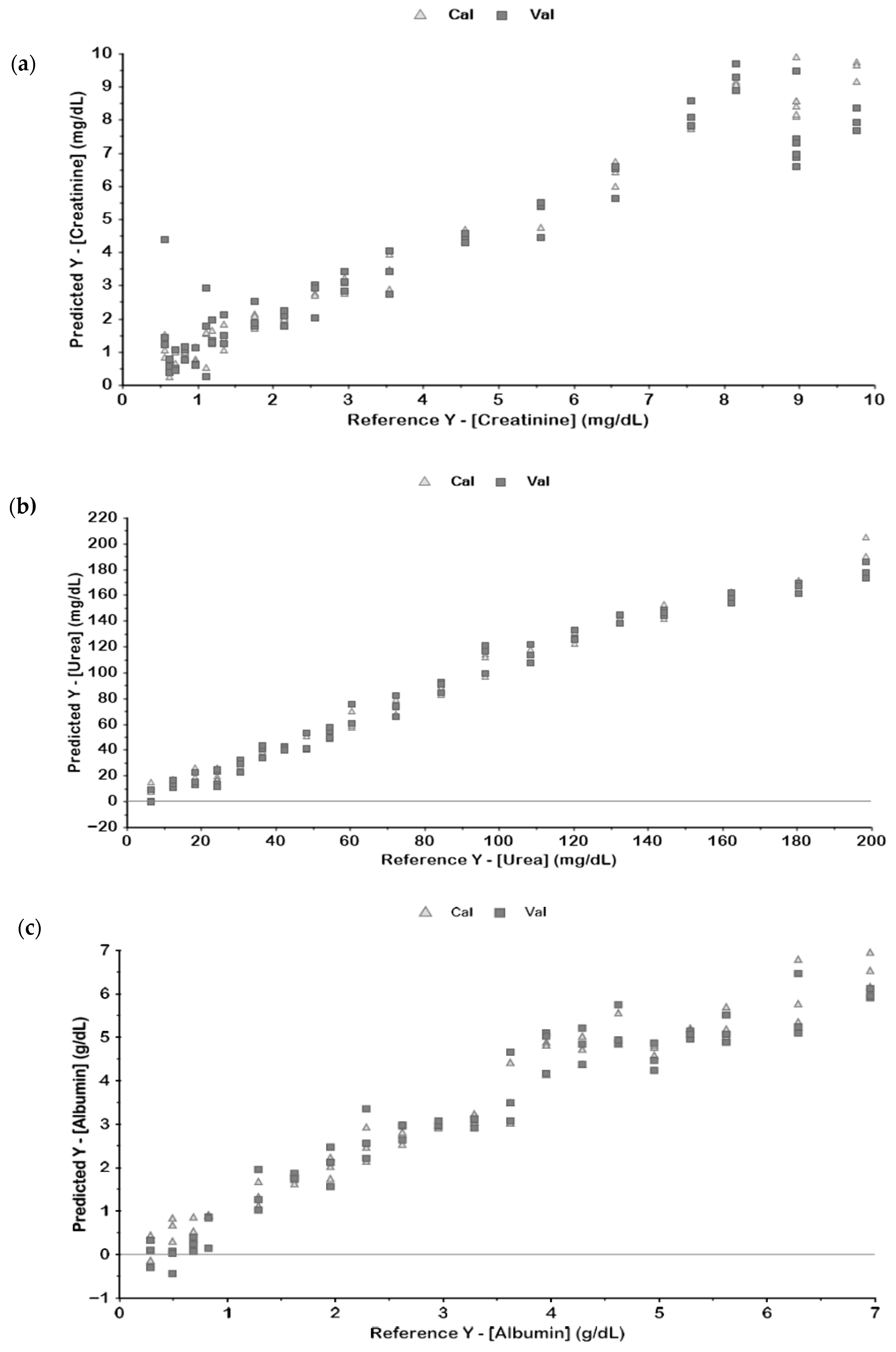

3.2. MIR Spectroscopic Analysis

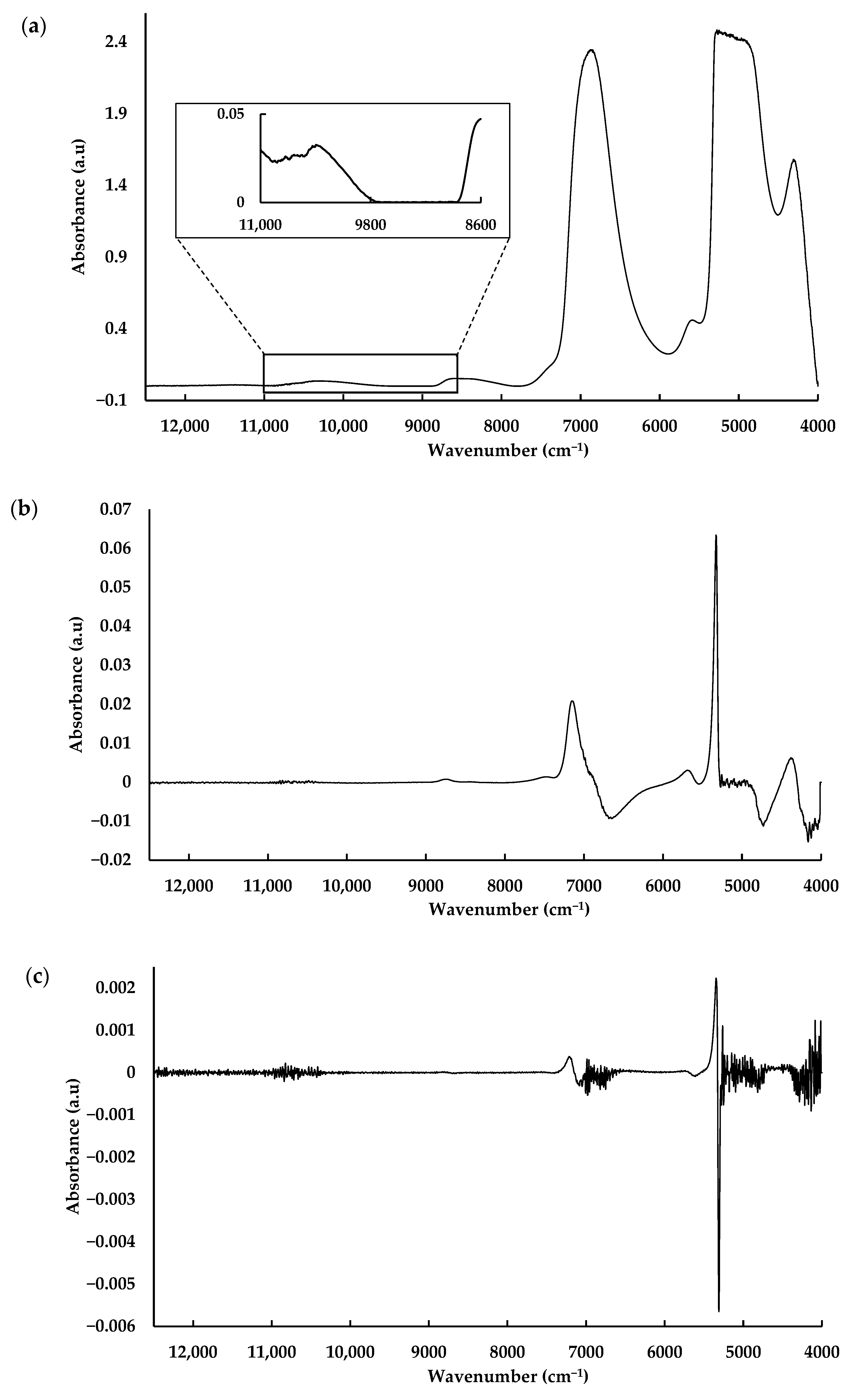

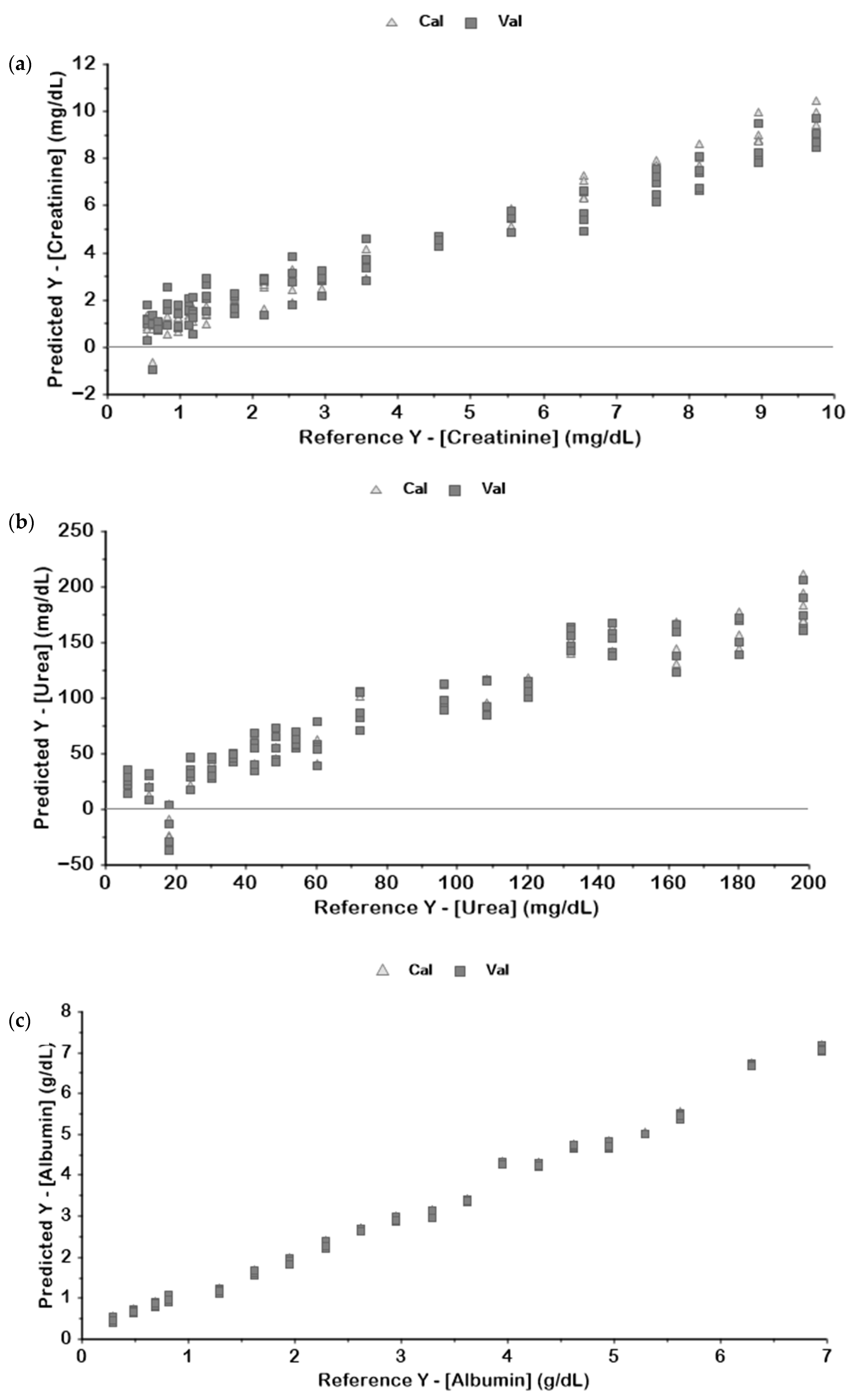

3.3. NIR Spectroscopic Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eckardt, K.U.; Coresh, J.; Devuyst, O.; Johnson, R.J.; Köttgen, A.; Levey, A.S.; Levin, A. Evolving importance of kidney disease: From subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet 2013, 382, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, X.; Jiang, J.; Yuan, C.; Xie, K.; Wang, K. Temporal trends in prevalence and disability of chronic kidney disease caused by specific etiologies: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J. Nephrol. 2024, 37, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckenmayer, A.; Siebler, N.; Haas, C.S. Pre-existing chronic kidney disease, aetiology of acute kidney injury and infection do not affect renal outcome and mortality. J. Nephrol. 2023, 37, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanone, G.T.; Júnior, M.S.d.C.; Bianchi, M.M.; Dias, C.C.; Macêdo, L.F.; Simões, N.S.; Passaglia, A.F.C.; Santos, G.T.d.; Leite, K.B.G. Manejo da Doença Renal Crônica: Importância do diagnóstico precoce e monitoramento contínuo. Lumen Virtus 2024, 15, 3184–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, V.A.; Tonelli, M.; Stanifer, J.W. The global burden of kidney disease and the sustainable development goals. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 96, 414–422D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Transforming Kidney Health and the Burden of CKD|AstraZeneca. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/articles/2023/transforming-kidney-health-burden-ckd.html (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Gounden, V.; Bhatt, H.; Jialal, I. Renal Function Tests. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507821/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Delrue, C.; De Bruyne, S.; Speeckaert, M.M. The Potential Use of Near- and Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy in Kidney Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Introduction to Near Infrared Spectroscopy—2014—Wiley Analytical Science. (n.d.). Available online: https://analyticalscience.wiley.com/content/article-do/introduction-near-infrared-spectroscopy (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Ozaki, Y.; Huck, C.W.; Beć, K.B. Near-IR Spectroscopy and Its Applications. In Molecular and Laser Spectroscopy: Advances and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, B.R.; Ramalhete, L.; Fonseca, L.P.; Calado, C.R.C. Fourier-transform mid-infrared (FT-MIR) spectroscopy in biomedicine. In Essential Techniques for Medical and Life Scientists: A Guide to Contemporary Methods and Current Applications with the Protocols: Part 2; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2020; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy—An Overview|ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/food-science/attenuated-total-reflectance-fourier-transform-infrared-spectroscopy (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Bonsante, F.; Ramful, D.; Binquet, C.; Samperiz, S.; Daniel, S.; Gouyon, J.B.; Iacobelli, S. Low Renal Oxygen Saturation at Near-Infrared Spectroscopy on the First Day of Life Is Associated with Developing Acute Kidney Injury in Very Preterm Infants. Neonatology 2019, 115, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorum, B.A.; Ozkan, H.; Cetinkaya, M.; Koksal, N. Regional oxygen saturation and acute kidney injury in premature infants. Pediatr. Int. 2021, 63, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.P.C.B.; Aguiar, E.M.G.; Cardoso-Sousa, L.; Caixeta, D.C.; Guedes, C.C.F.V.; Siqueira, W.L.; Maia, Y.C.P.; Cardoso, S.V.; Sabino-Silva, R. Differential Molecular Signature of Human Saliva Using ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis. Braz. Dent. J. 2019, 30, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangwanichgapong, K.; Klanrit, P.; Chatchawal, P.; Wongwattanakul, M.; Pongskul, C.; Chaichit, R.; Hormdee, D. Salivary attenuated total reflectance-fourier transform infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometric analysis: A potential point-of-care approach for chronic kidney disease screening. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2025, 52, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangwanichgapong, K.; Klanrit, P.; Chatchawal, P.; Wongwattanakul, M.; Pongskul, C.; Chaichit, R.; Hormdee, D. Identification of molecular biomarkers in human serum for chronic kidney disease using attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 334, 125941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Fan, H.; Shang, P.; Sun, Y.; Tian, W.; Ma, G. Detection of Acute Kidney Injury Induced by Gentamicin in a Rat Model by Aluminum-Foil-Assisted ATR-FT-IR Spectroscopy. Spectroscopy 2023, 38, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eGFR Equations for Adults—NIDDK. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/research-funding/research-programs/kidney-clinical-research-epidemiology/laboratory/glomerular-filtration-rate-equations/adults (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Explaining Your Kidney Test Results: A Tool for Clinical Use—NIDDK. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/professionals/advanced-search/explain-kidney-test-results (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Chronic Kidney Disease Tests & Diagnosis—NIDDK. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease/chronic-kidney-disease-ckd/tests-diagnosis (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Low-Ying, S.; Shaw, R.A.; Leroux, M.; Mantsch, H.H. Quantitation of glucose and urea in whole blood by mid-infrared spectroscopy of dry films. Vib. Spectrosc. 2002, 28, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, T.E.; Höskuldsson, A.T.; Bjerrum, P.J.; Verder, H.; Sørensen, L.; Bratholm, P.S.; Christensen, B.; Jensen, L.S.; Jensen, M.A.B. Simultaneous determination of glucose, triglycerides, urea, cholesterol, albumin and total protein in human plasma by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: Direct clinical biochemistry without reagents. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 47, 1306–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, R.; Kirchler, C.G.; Schirmeister, Z.L.; Roth, A.; Mäntele, W.; Huck, C.W. Hemodialysis monitoring using mid- and near-infrared spectroscopy with partial least squares regression. J. Biophotonics 2018, 11, e201700365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoşafçı, G.; Klein, O.; Oremek, G.; Mäntele, W. Clinical chemistry without reagents? An infrared spectroscopic technique for determination of clinically relevant constituents of body fluids. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M. Determination of Concentrations of Human Serum Albumin in Phosphate Buffer Solutions Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in the Region of 750-2500 nm. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224774435_Determination_of_concentrations_of_human_serum_albumin_in_phosphate_buffer_solutions_using_near-infrared_spectroscopy_in_the_region_of_750-2500_nm (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Shaw, R.A.; Kotowich, S.; Mantsch, H.H.; Leroux, M. Quantitation of protein, creatinine, and urea in urine by near-infrared spectroscopy. Clin. Biochem. 1996, 29, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzaniti, J.L.; Jeng, T.W.; McDowell, L.; Oosta, G.M. Preliminary investigation of near-infrared spectroscopic measurements of urea, creatinine, glucose, protein, and ketone in urine. Clin. Biochem. 2001, 34, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, I.; Ogawa, M.; Seino, K.; Nogawa, M.; Naito, H.; Yamakoshi, K.I.; Tanaka, S. Reagentless Estimation of Urea and Creatinine Concentrations Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy for Spot Urine Test of Urea-to-Creatinine Ratio. Adv. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 7, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.L.; Evans, R.D.R.; Unwin, R.J.; Norman, J.T.; Rich, P.R. Assessment of Measurement of Salivary Urea by ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy to Screen for CKD. Kidney360 2022, 3, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, Z.H.; Abookasis, D. Determination of creatinine level in patient blood samples by Fourier NIR spectroscopy and multivariate analysis in comparison with biochemical assay. J. Innov. Opt. Health Sci. 2019, 12, 1950015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, C.; Gao, Y.; Cao, H. Quantitative analysis of albumin and glucose based on near-infrared fibre-optic SPR sensing. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2025, 95, 104436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.W.; Pollard, A. Near-infrared spectroscopic determination of serum total proteins, albumin, globulins, and urea. Clin. Biochem. 1993, 26, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolite | Pre-Processing | Latent Variables | Calibration | Validation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |||

| Creatinine | Raw | 8 | 0.97 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 1.54 |

| BC | 9 | 0.98 | 0.41 | 0.78 | 1.50 | |

| BC + SNV | 10 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.99 | |

| BC + SNV + 1D | 5 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.90 | 0.99 | |

| BC + SNV + 2D | 6 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.84 | 1.31 | |

| Urea | Raw | 4 | 0.98 | 8.6 | 0.96 | 11.7 |

| BC | 3 | 0.98 | 8.4 | 0.97 | 10.3 | |

| BC + SNV | 2 | 0.96 | 10.8 | 0.96 | 11.6 | |

| BC + SNV + 1D | 3 | 0.99 | 6.6 | 0.98 | 9.1 | |

| BC + SNV + 2D | 2 | 0.96 | 11.8 | 0.94 | 14.0 | |

| Albumin | Raw | 4 | 0.95 | 0.43 | 0.93 | 0.53 |

| BC | 8 | 0.99 | 0.21 | 0.95 | 0.45 | |

| BC + SNV | 7 | 0.96 | 0.39 | 0.92 | 0.54 | |

| BC + SNV + 1D | 4 | 0.96 | 0.39 | 0.92 | 0.57 | |

| BC + SNV + 2D | 3 | 0.94 | 0.49 | 0.82 | 0.84 | |

| Metabolite | Pre-Processing | Latent Variables | Calibration | Validation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |||

| Creatinine | Raw | 10 | 0.97 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 2.63 |

| BC | 8 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.21 | 2.70 | |

| BC + SNV | 9 | 0.96 | 0.59 | 0.28 | 2.58 | |

| BC + SNV + 1D | 2 | 0.09 | 2.87 | 0.07 | 2.92 | |

| BC + SNV + 2D | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| BC + UVN | 10 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 2.58 | |

| 1D | 2 | 0.09 | 2.88 | 0.06 | 2.96 | |

| 2D | 2 | 0.11 | 2.84 | 0.06 | 2.95 | |

| Urea | Raw | 5 | 0.94 | 14.63 | 0.79 | 27.21 |

| BC | 5 | 0.93 | 15.10 | 0.69 | 32.77 | |

| BC + SNV | 5 | 0.95 | 13.14 | 0.7 | 32.38 | |

| BC + SNV + 1D | 1 | 0.64 | 35.14 | 0.23 | 52.20 | |

| BC + SNV + 2D | 1 | 0.55 | 39.29 | 0 | 60.41 | |

| BC + UVN | 5 | 0.96 | 12.32 | 0.71 | 31.86 | |

| 1D | 1 | 0.65 | 34.63 | 0.23 | 51.8 | |

| 2D | 1 | 0.55 | 39.25 | 0.02 | 58.60 | |

| Albumin | Raw | 2 | 0.99 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.23 |

| BC | 3 | 0.99 | 0.17 | 0.99 | 0.18 | |

| BC + SNV | 3 | 0.98 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.30 | |

| BC + SNV + 1D | 3 | 0.98 | 0.26 | 0.98 | 0.29 | |

| BC + SNV + 2D | 6 | 0.98 | 0.24 | 0.8 | 0.89 | |

| BC + UVN | 4 | 0.99 | 0.20 | 0.99 | 0.23 | |

| 1D | 3 | 0.98 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.27 | |

| 2D | 7 | 0.99 | 0.22 | 0.80 | 0.88 | |

| Metabolite | Spectral Sub-Region | Latent Variables | Calibration | Validation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |||

| Creatinine | Full Spectrum | 10 | 0.98 | 0.390 | 0.29 | 2.579 |

| 3rd Overtone | 7 | 0.98 | 0.377 | 0.67 | 1.745 | |

| 2nd Overtone | 1 | 0.04 | 2.944 | 0.02 | 3.010 | |

| 1st Overtone | 1 | 0.04 | 2.944 | 0 | 3.044 | |

| Combination Bands | 3 | 0.16 | 2.768 | 0.10 | 2.890 | |

| 11,000–8600 | 6 | 0.98 | 0.399 | 0.94 | 0.727 | |

| 7800–7050 | 1 | 0.01 | 2.989 | 0 | 3.140 | |

| 5800–5300 | 1 | 0.04 | 2.955 | 0.01 | 3.030 | |

| 4700–4400 | 1 | 0.02 | 2.977 | 0 | 3.032 | |

| Urea | Full Spectrum | 5 | 0.96 | 12.324 | 0.71 | 31.856 |

| 3rd Overtone | 5 | 0.99 | 6.769 | 0.73 | 30.809 | |

| 2nd Overtone | 3 | 0.51 | 40.803 | 0.41 | 45.911 | |

| 1st Overtone | 3 | 0.68 | 33.050 | 0.48 | 43.191 | |

| Combination Bands | 4 | 0.9 | 18.787 | 0.66 | 34.740 | |

| 11,000–8600 | 4 | 0.94 | 13.927 | 0.75 | 29.719 | |

| 7800–7050 | 3 | 0.54 | 39.824 | 0.44 | 44.019 | |

| 5800–5300 | 10 | 0.82 | 25.044 | 0.58 | 38.200 | |

| 4700–4400 | 4 | 0.92 | 16.359 | 0.90 | 19.038 | |

| Albumin | Full Spectrum | 4 | 0.99 | 0.200 | 0.99 | 0.229 |

| 3rd Overtone | 5 | 0.99 | 0.212 | 0.95 | 0.429 | |

| 2nd Overtone | 3 | 0.99 | 0.231 | 0.98 | 0.241 | |

| 1st Overtone | 2 | 0.98 | 0.266 | 0.98 | 0.276 | |

| Combination Bands | 4 | 0.98 | 0.247 | 0.98 | 0.290 | |

| 11,000–8600 | 6 | 0.99 | 0.192 | 0.97 | 0.334 | |

| 7800–7050 | 5 | 0.98 | 0.284 | 0.97 | 0.355 | |

| 5800–5300 | 5 | 0.99 | 0.184 | 0.99 | 0.211 | |

| 4700–4400 | 2 | 0.99 | 0.187 | 0.99 | 0.191 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano, D.; Zoio, P.; Fonseca, L.P.; Calado, C.R.C. Comparison of Mid and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy to Predict Creatinine, Urea and Albumin in Serum Samples as Biomarkers of Renal Function. Biosensors 2025, 15, 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120786

Serrano D, Zoio P, Fonseca LP, Calado CRC. Comparison of Mid and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy to Predict Creatinine, Urea and Albumin in Serum Samples as Biomarkers of Renal Function. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):786. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120786

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano, Diogo, Paulo Zoio, Luís P. Fonseca, and Cecília R. C. Calado. 2025. "Comparison of Mid and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy to Predict Creatinine, Urea and Albumin in Serum Samples as Biomarkers of Renal Function" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120786

APA StyleSerrano, D., Zoio, P., Fonseca, L. P., & Calado, C. R. C. (2025). Comparison of Mid and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy to Predict Creatinine, Urea and Albumin in Serum Samples as Biomarkers of Renal Function. Biosensors, 15(12), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120786