Wearable Electrochemical Biosensors for Monitoring and Management of Chronic Wounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Chronic Wounds and Implications for Biosensor Design

2.1. Definition of Chronic Wound

2.2. Pathophysiological Characteristics of Chronic Wound

2.3. Healing Impairment Factors and Sensing Targets

3. Recent Advances in Wearable Electrochemical Biosensors for Wound Management

3.1. Development Status of Functional Materials

3.2. Closed-Loop Theranostic Systems

3.3. Multi-Modal Sensing and AI-Enhanced Diagnostic Analytics

4. Electrochemical Biosensors for Wound Monitoring and Healing

4.1. Real-Time Wound Monitoring

4.2. Early Detection of Wound Infection

4.3. Smart Sensing-Actuating Platforms for Intelligent Wound Management

5. Challenges and Limitations

5.1. Technical Challenges

5.2. Clinical Translation

5.3. Power Management

6. Advancing Technical Solutions: Addressing Key Barriers in Wearable Wound Sensing Technology

6.1. Multimodal Sensing and Signal Enhancement

6.2. Self-Powered Sensing and Active Therapeutics

6.3. Intelligent Telemedicine for Dynamic Wound Management

7. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Su, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yimamumaimaiti, T.; Hu, D.; Zhu, J.J.; Zhang, J.R. A self-powered and drug-free diabetic wound healing patch breaking hyperglycemia and low H2O2 limitations and precisely sterilizing driven by electricity. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Lv, Y.; Niu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, H.; Fan, K.; Wang, X. Zinc Oxide-Enhanced Copper Sulfide Nanozymes Promote the Healing of Infected Wounds by Activating Immune and Inflammatory Responses. Small 2024, 21, 2406356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Su, Y.J.; Wang, J.Y.; Romanova, S.; DiMaio, D.J.; Xie, J.W.; Zhao, S.W. A Highly Efficacious Electrical Biofilm Treatment System for Combating Chronic Wound Bacterial Infections. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2208069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.H.; Xie, H.L.; Zhang, J.M.; Tang, C.; Tian, S.B.; Yuan, P.; Sun, C.L.; Cui, C.; Zhong, Q.; Xu, F.N.; et al. Hydrogel-Based Sequential Photodynamic Therapy Promotes Wound Healing by Targeting Wound Infection and Inflammation. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 12107–12117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Chen, P.; Liang, J.J.; Wu, Z.H.; Jin, H.Q.; Xu, T.P.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Ma, H.F.; Cong, W.T.; Wang, X.; et al. Inhibition of CK2α accelerates skin wound healing by promoting endothelial cell proliferation through the Hedgehog signaling pathway. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derichsweiler, C.; Herbertz, S.; Kruss, S. Optical Bionanosensors for Sepsis Diagnostics. Small 2025, 21, e2409042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhuvilakku, R.; Hong, Y. Portable Sensing Probe for Real-Time Quantification of Ammonia in Blood Samples. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 47242–47256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Xiu, W.J.; Ding, M.; Shan, J.Y.; Mou, Y.B. Photocatalytic Cu2WS4 Nanocrystals for Efficient Bacterial Killing and Biofilm Disruption. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 2735–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.P.; Wang, F.Y.; Zhang, X.X.; Shang, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.J. Living microecological hydrogels for wound healing. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, D.; Dankers, P.; Roche, E.; Wang, H. Engineering Active Materials for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2412651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Tao, J.; Zhang, A.; Chen, R.; Jiang, T.; Zhao, X. A Zn-MOF-GOx-based cascade nanoreactor promotes diabetic infected wound healing by NO release and microenvironment regulation. Acta Biomater. 2024, 182, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.L.; Shao, H.H.; Lu, X.Z.; Wang, W.J.; Zhang, J.R.; Song, R.B.; Zhu, J.J. A glucose/O2 fuel cell-based self-powered biosensor for probing a drug delivery model with self-diagnosis and self-evaluation. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 8482–8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.L.; Zhu, W.L.; Zhang, J.R.; Zhu, J.J. Miniaturized Microfluidic Electrochemical Biosensors Powered by Enzymatic Biofuel Cell. Biosensors 2023, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.B.; Xu, J.; Huang, K.J.; Guo, Y.T.; Wang, R.J. Precise and real-time detection of miRNA-141 realized on double-drive strategy triggered by sandwich-graphdiyne and energy conversion device. Sens. Actuators B 2023, 389, 133902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.B.; Li, Y.J.; Huang, K.J. Smartphone-Assisted Flexible Electrochemical Sensor Platform by a Homology DNA Nanomanager Tailored for Multiple Cancer Markers Field Inspection. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 13305–13312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, E.S.; Wang, C.; Gao, W. A soft bioaffinity sensor array for chronic wound monitoring. Matter 2021, 4, 2613–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Pei, D.; Yang, Y.; Xu, K.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; et al. Green Tea Derivative Driven Smart Hydrogels with Desired Functions for Chronic Diabetic Wound Treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009442. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.B.; Huang, K.J.; Hou, Y.Y.; Sun, X.X.; Li, J.Q. Real-Time Biosensor Platform Based on Novel Sandwich Graphdiyne for Ultrasensitive Detection of Tumor Marker. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 16980–16986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Wound Healing: Cellular Mechanisms and Pathological Outcomes. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Ishida, Y. Molecular Pathology of Wound Healing. Forensic Sci. Int. 2010, 203, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.H.; Chen, L.Q.; Liu, J.H.; Liu, Y.; Qu, L.L.; Zhu, C.Z.; Zhu, J.J.; Lin, Y.H.; Dong, X.C. Boron nitride nanosheets for biosensors and biomedicine. TrAC-Trend Anal. Chem. 2025, 191, 118379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, H.; Dong, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhou, J. Enzyme-Free Photoelectrochemical Biosensor Based on the CoSensitization Effect Coupled with Dual Cascade Toehold-Mediated Strand Displacement Amplification for the Sensitive Detection of MicroRNA-21. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 11633–11641. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.B.; Luo, X.Q.; Xing, Y.Q.; Huang, K.J. Visual self-powered platform for ultrasensitive heavy metal detection designed on graphdiyne/graphene heterojunction and DNAzyme-triggered DNA circuit strategy. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 150151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Bao, X.; Zhang, M.; Fang, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Liu, R.; Kim, S.H.; Baughman, R.H.; Ding, J. Recent Advances in Carbon Nanotube-Based Energy Harvesting Technologies. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2303035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Pyun, K.R.; Lee, M.T.; Lee, H.B.; Ko, S.H. Recent Advances in Sustainable Wearable Energy Devices with Nanoscale Materials and Macroscale Structures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 32, 2110535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Sun, Z.; Shao, Y.; Gao, L.; Huang, R.; Shao, Y.; Kaner, R.B.; Sun, J. Ultrafast rechargeable Zn micro-batteries endowing a wearable solar charging system with high overall efficiency. Energ. Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 1602–1611. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, L.J.; Zhu, Y.L.; Qin, X.Y.; Chai, S.L.; Liu, G.X.; Su, W.T.; Lv, Q.Z.; Li, D. Magnetic biohybrid microspheres for protein purification and chronic wound healing in diabetic mice. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 130671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.J.; Xu, R.; He, S.B.; Sun, R.; Wang, G.N.; Wei, S.Y.; Yan, X.Y.; Fan, K.L. Nanozyme-driven multifunctional dressings: Moving beyond enzyme-like catalysis in chronic wound treatment. Mil. Med. Res. 2025, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Song, Y.X.; Yao, H.Q.; Min, Q.H.; Zhang, J.R.; Zhu, J.J. Multistage Photoactivatable Zinc-Responsive Nanodevices for Monitoring and Regulating Dysfunctional Islet β-Cells. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 6607–6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Krieg, T.; Davidson, J.M. Inflammation in Wound Repair: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.S.; Madden, L.; Chew, S.Y.; Becker, D.L. Drug therapies and delivery mechanisms to treat perturbed skin wound healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 149–150, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.-K.; Chang, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, B.; Guevara, B.E.K.; Hsu, C.-K. Inflammation in Wound Healing and Pathological Scarring. Adv. Wound Care 2023, 12, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.-X.; Chen, Y.-B.; Li, J.-Y.; Shen, J.; Zeng, H.-Q. Silk Nonwoven Fabric-Based Dressing with Antibacterial and ROS-Scavenging Properties for Modulating Wound Microenvironment and Promoting Diabetic Wound Healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 25, 2405151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, H.; Xu, Y.; Kong, B.; Tan, Q. Chronic wounds: Pathological characteristics and their stem cell-based therapies. Eng. Regen. 2023, 4, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Hu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Du, L.; Hu, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Xie, X.; Cheng, P.; Liao, J.; Lu, L.; et al. MMP-9 responsive hydrogel promotes diabetic wound healing by suppressing ferroptosis of endothelial cells. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 43, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, D.; Huang, C.; Ding, X.; Wang, T.; Zhuo, M.; Wang, H.; Kai, S.; Cheng, N. Development of an aminoguanidine hybrid hydrogel composites with hydrogen and oxygen supplying performance to boost infected diabetic wound healing. J. Colloid Interface Sci 2025, 691, 137401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Zhu, H.F.; Che, J.Y.; Xu, Y.; Tan, Q.; Zhao, Y.J. Stem cell niche-inspired microcarriers with ADSCs encapsulation for diabetic wound treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 130671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokoena, D.; Dhilip Kumar, S.S.; Houreld, N.N.; Abrahamse, H. Role of photobiomodulation on the activation of the Smad pathway via TGF-β in wound healing. J. Photoch. Photobio. B 2018, 189, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.-P.; Wang, P.D.; Tsai, F.-C.; Deng, Y.-H.; Wang, J.R.; Williams, D.F.; Yu, S.-H.; Wei, H.-J.; Dubey, N.K. Adipose-derived Stem Cells Attenuates Diabetic Osteoarthritis via Inhibition of Glycation-mediated Inflammatory Cascade. Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 483–496. [Google Scholar]

- Herbstein, F.; Sapochnik, M.; Attorresi, A.; Pollak, C.; Senin, S.; Gonilski-Pacin, D.; Ciancio del Giudice, N.; Fiz, M.; Elguero, B.; Fuertes, M.; et al. The SASP factor IL-6 sustains cell-autonomous senescent cells via a cGAS-STING-NFκB intracrine senescent noncanonical pathway. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Singla, R.K.; Wang, C. Application of Biomaterials in Diabetic Wound Healing: The Recent Advances and Pathological Aspects. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ma, C.; Rong, X.; Zou, S.; Liu, X. Immunomodulatory ECM-like Microspheres for Accelerated Bone Regeneration in Diabetes Mellitus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 2377–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Bahojb Noruzi, E.; Chidar, E.; Jafari, M.; Davoodi, F.; Kashtiaray, A.; Ghafori Gorab, M.; Masoud Hashemi, S.; Javanshir, S.; Ahangari Cohan, R.; et al. Applications of carbon-based conductive nanomaterials in biosensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442, 136183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Cheng, N.; Luo, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, W.; Du, D. Recent advances in nanomaterials-based electrochemical (bio)sensors for pesticides detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 132, 116041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, H.-B.; Luo, J.-Q.; Wang, Q.-W.; Xu, B.; Hong, S.; Yu, Z.-Z. Highly Electrically Conductive Three-Dimensional Ti3C2Tx MXene/Reduced Graphene Oxide Hybrid Aerogels with Excellent Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Performances. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 11193–11202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallineni, S.S.K.; Behlow, H.; Dong, Y.; Bhattacharya, S.; Rao, A.M.; Podila, R. Facile and robust triboelectric nanogenerators assembled using off-the-shelf materials. Nano Energy 2017, 35, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Wang, H.; He, J.; Qi, K. Fluorine-free and breathable polyethylene terephthalate/polydimethylsiloxane (PET/PDMS) fibrous membranes with robust waterproof property. Compos. Commun. 2023, 40, 101589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercea, M.; Biliuta, G.; Avadanei, M.; Baron, R.I.; Butnaru, M.; Coseri, S. Self-healing hydrogels of oxidized pullulan and poly(vinyl alcohol). Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 206, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, N.; Poggi, G.; Chelazzi, D.; Giorgi, R.; Baglioni, P. Poly(vinyl alcohol)/poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) hydrogels for the cleaning of art. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 536, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Wang, F.T.; Han, Z.W.; Huang, K.J.; Wang, X.M.; Liu, Z.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Lu, Y.F. Construction of sandwiched self-powered biosensor based on smart nanostructure and capacitor: Toward multiple signal amplification for thrombin detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 304, 127418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifringer, L.; De Windt, L.; Bernhard, S.; Amos, G.; Clément, B.; Duru, J.; Tibbitt, M.W.; Tringides, C.M. Photopatterning of conductive hydrogels which exhibit tissue-like properties. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 10272–10284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjadi, J.U.; Aymon, B.F.G.; Carton, M.; Portela, C.M. Double-network-inspired mechanical metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 945–954. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, R.; Sun, T.L.; Saruwatari, Y.; Kurokawa, T.; King, D.R.; Gong, J.P. Creating Stiff, Tough, and Functional Hydrogel Composites with Low-Melting-Point Alloys. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706885. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, A.; Gong, S.; Cheng, W. Wearable Smart Bandage-Based Bio-Sensors. Biosensors 2023, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.H.; Wu, X.T.; Cao, S.T.; Zhao, Y.F.; Lin, Y.; Xu, Y.R.; Ning, X.H.; Kong, D.S. Stretchable and Skin-Attachable Electronic Device for Remotely Controlled Wearable Cancer Therapy. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Wang, L.; Han, F.; Bian, S.; Meng, F.; Qi, W.; Zhai, X.; Li, H.; Wu, J.; Pan, X.; et al. A highly stretchable smart dressing for wound infection monitoring and treatment. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 26, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, C.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Ning, N.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y. Highly Stretchable and Conductive Self-Healing Hydrogels for Temperature and Strain Sensing and Chronic Wound Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 40990–40999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, C.; Song, Y.; Liu, C.; An, H.; Yu, P.; Wang, H.; Xiang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yeung, K.W.K.; et al. A contractile-programmable sensor patch with antibacterial and immunomodulatory properties for infected wound management. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, P.Y.; Yang, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Yang, K.R.; Cheng, Y.H.; Yao, H.W.; Zhang, Z.T. Current Progress and Outlook of Nano-Based Hydrogel Dressings for Wound Healing. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, N.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Hua, R.; Wang, K. A pH-Resolved Colorimetric Biosensor for Simultaneous Multiple Target Detection. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 2159–2165. [Google Scholar]

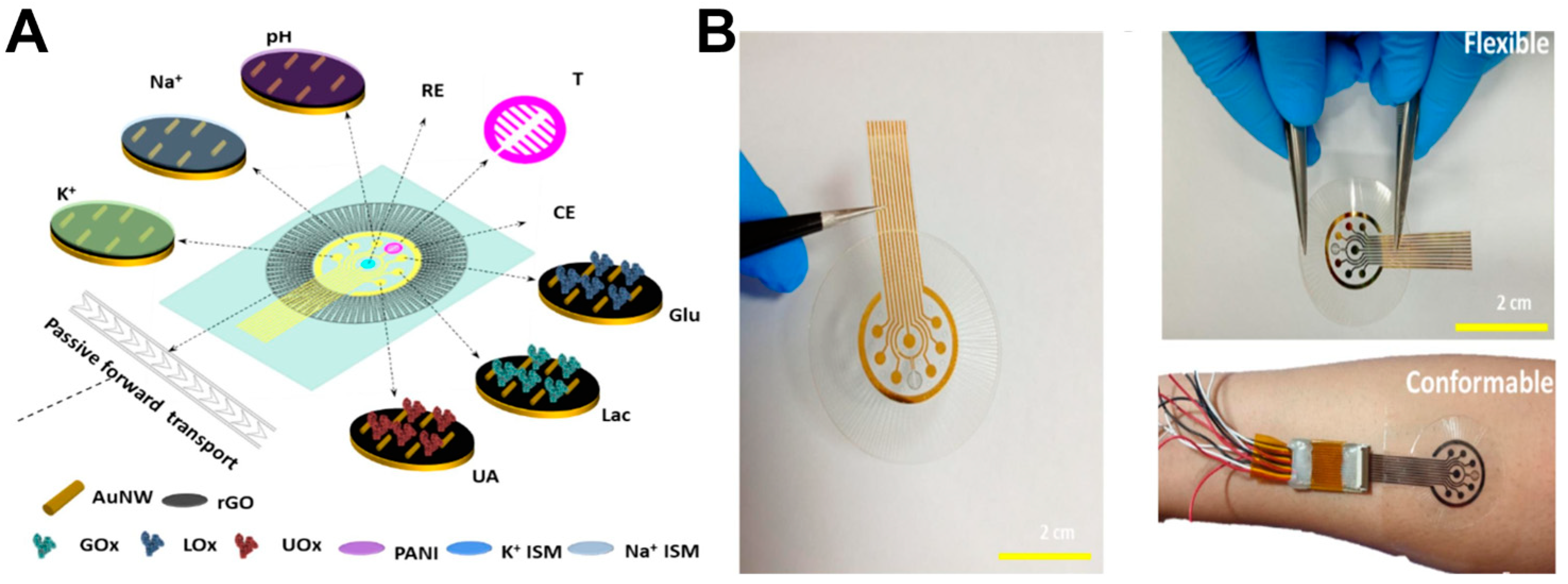

- Shirzaei Sani, E.; Xu, C.; Wang, C.; Song, Y.; Min, J.; Tu, J.; Solomon, S.A.; Li, J.; Banks, J.L.; Armstrong, D.G.; et al. A stretchable wireless wearable bioelectronic system for multiplexed monitoring and combination treatment of infected chronic wounds. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, A.; Gunda, V.; Thai, K.; Prasad, S. Inflammatory Stimuli Responsive Non-Faradaic, Ultrasensitive Combinatorial Electrochemical Urine Biosensor. Sensors 2022, 22, 7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.; Karim, W.; Gelman, J.; Raza, M. Ethical data acquisition for LLMs and AI algorithms in healthcare. Npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Río-Sancho, S.; Christen-Zaech, S.; Martinez, D.A.; Pünchera, J.; Guerrier, S.; Laubach, H.J. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography coupled with artificial intelligence algorithms as tool to investigate wound healing: A prospective, randomized, single-blinded pilot study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 39, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Duan, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Shi, T.; Xu, Y.; Peng, Q.; Hsieh, D.-J.; Chang, K.-C. Wound monitoring based on machine learning using a pro-healing acellular dermal matrix. Device 2025, 3, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhang, M. Liposozyme for wound healing and inflammation resolution. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 1083–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, S.; Ling, Q.; Wang, R.; Liu, T.; Yu, H.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, K.; Bian, L.; Liao, W. Nanozyme-Reinforced Hydrogel Spray as a Reactive Oxygen Species-Driven Oxygenator to Accelerate Diabetic Wound Healing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2504829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.L.; Demers, M.; Martinod, K.; Gallant, M.; Wang, Y.; Goldfine, A.B.; Kahn, C.R.; Wagner, D.D. Diabetes primes neutrophils to undergo NETosis, which impairs wound healing. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Lu, T.; Huang, C.; Zheng, D.; Gong, G.; Chu, X.; Wang, X.; Lai, H.; Ma, L.; Jiang, L.; et al. Bioinspired Sonodynamic Nano Spray Accelerates Infected Wound Healing via Targeting and Disturbing Bacterial Metabolism. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2315576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.S.; Sharifuzzaman, M.; Islam, Z.; Assaduzaman, M.; Lee, Y.; Kim, D.; Islam, M.R.; Kang, H.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.H.; et al. A flexible and multimodal biosensing patch integrated with microfluidics for chronic wound monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.S.; Browne, K.; Kirchner, N.; Koh, A. Adhesive-Free, Stretchable, and Permeable Multiplex Wound Care Platform. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLister, A.; McHugh, J.; Cundell, J.; Davis, J. New Developments in Smart Bandage Technologies for Wound Diagnostics. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 5732–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Khatib, M.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, C.; Omar, R.; Saliba, W.; Wu, W.; et al. Highly Efficient Self-Healing Multifunctional Dressing with Antibacterial Activity for Sutureless Wound Closure and Infected Wound Monitoring. Adv. Mater. 2021, 34, e2106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhong, G.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X. Self-Sterilizing Microneedle Sensing Patches for Machine Learning-Enabled Wound pH Visual Monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2315067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Luan, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, K.; Luo, Q.; Ye, S.; Wang, W.; Dan, R.; Shu, Z.; Huang, Y.; et al. Endoscopy Deliverable and Mushroom-Cap-Inspired Hyperboloid-Shaped Drug-Laden Bioadhesive Hydrogel for Stomach Perforation Repair. ACS Nano 2022, 17, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, K.; Ullah, A.; Rezai, P.; Hasan, A.; Amirfazli, A. Recent Advances in Biosensors for Real-Time Monitoring of pH, Temperature, and Oxygen in Chronic Wounds. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 22, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, F.; Serafini, M.; Gualandi, I.; Arcangeli, D.; Decataldo, F.; Possanzini, L.; Tessarolo, M.; Tonelli, D.; Fraboni, B.; Scavetta, E. Advanced Wound Dressing for Real-Time pH Monitoring. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2366–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galliani, M.; Diacci, C.; Berto, M.; Sensi, M.; Beni, V.; Berggren, M.; Borsari, M.; Simon, D.T.; Biscarini, F.; Bortolotti, C.A. Flexible Printed Organic Electrochemical Transistors for the Detection of Uric Acid in Artificial Wound Exudate. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2001218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Deng, S.; Song, C.; Fu, X.; Zhang, N.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhan, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, M.; et al. Pd@Au Nanoframe Hydrogels for Closed-Loop Wound Therapy. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 15069–15080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

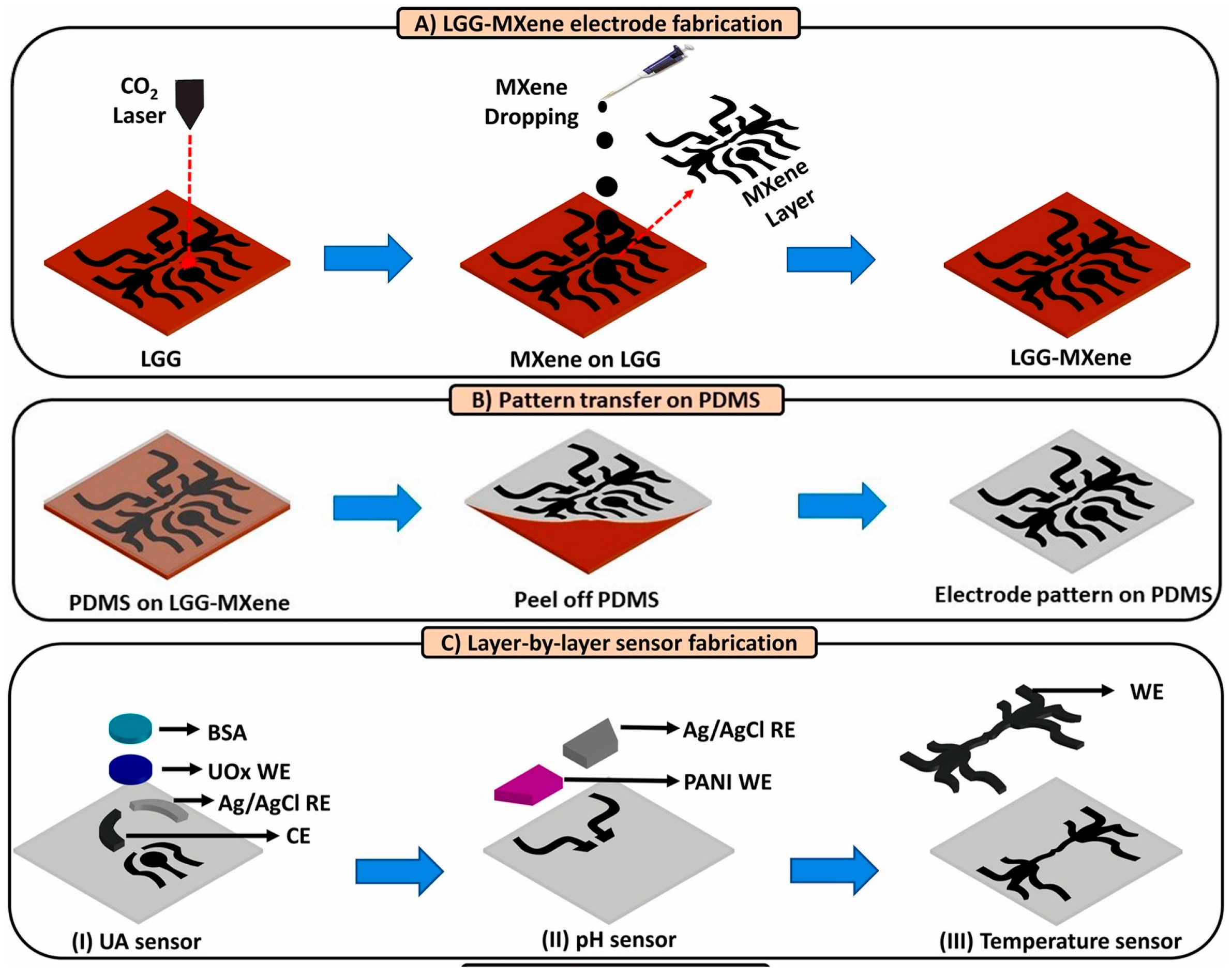

- Sharifuzzaman, M.; Chhetry, A.; Zahed, M.A.; Yoon, S.H.; Park, C.I.; Zhang, S.; Chandra Barman, S.; Sharma, S.; Yoon, H.; Park, J.Y. Smart bandage with integrated multifunctional sensors based on MXene-functionalized porous graphene scaffold for chronic wound care management. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 169, 112637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, J.; Yang, J.; Du, Z.; Zhao, W.; Guo, H.; Wen, C.; Li, Q.; Sui, X.; et al. A Multifunctional Pro-Healing Zwitterionic Hydrogel for Simultaneous Optical Monitoring of pH and Glucose in Diabetic Wound Treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 30, 1905493. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Deshpande, M.; Niu, Y.; Kachwala, I.; Flores-Bellver, M.; Megarity, H.; Nuse, T.; Babapoor-Farrokhran, S.; Ramada, M.; Sanchez, J.; et al. HIF-1α accumulation in response to transient hypoglycemia may worsen diabetic eye disease. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 111976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Chang, L.; Tang, G.; Ye, W.; Xu, Y.; Tulufu, N.; Dan, Z.; Qi, J.; Deng, L.; Li, C. Activation of the osteoblastic HIF-1α pathway partially alleviates the symptoms of STZ-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus via RegIIIγ. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1574–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Liang, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, G.; Yu, B.; Li, Y.; Xu, F.-J. Glucose-responsive hydrogel with adaptive insulin release to modulate hyperglycemic microenvironment and promote wound healing. Biomaterials 2025, 326, 123641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, W.; Xiong, Y.; Ahmad, W.; Dutta, D.; Mukerabigwi, J.F.; Theoneste, M.; Lu, T.; Ge, Z. Multifunctional Bacterial Cellulose Hydrogel Membranes with Antibacterial and Tissue-Regenerating Properties for Treatment of Infected Diabetic Wound. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 5320–5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tun, T.N.; Hong, S.-h.; Mercer-Chalmers, J.D.; Laabei, M.; Young, A.E.R.; Jenkins, A.T.A. Development of a prototype wound dressing technology which can detect and report colonization by pathogenic bacteria. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 30, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.; Hu, X.; Lee, C.-Y.; Zhang, A.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, X.; Wei, J.; et al. A wearable electrochemical fabric for cytokine monitoring. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 232, 115301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumar, A.; Narasimhan, M.; Li, Q.-Z.; Mahimainathan, L.; Hitto, I.; Fuda, F.; Batra, K.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, C.; Schoggins, J.; et al. In-Depth Evaluation of a Case of Presumed Myocarditis After the Second Dose of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine. Circulation 2021, 144, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Nguyen, D.T.; Yeo, T.; Lim, S.B.; Tan, W.X.; Madden, L.E.; Jin, L.; Long, J.Y.K.; Aloweni, F.A.B.; Liew, Y.J.A.; et al. A flexible multiplexed immunosensor for point-of-care in situ wound monitoring. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg9614. [Google Scholar]

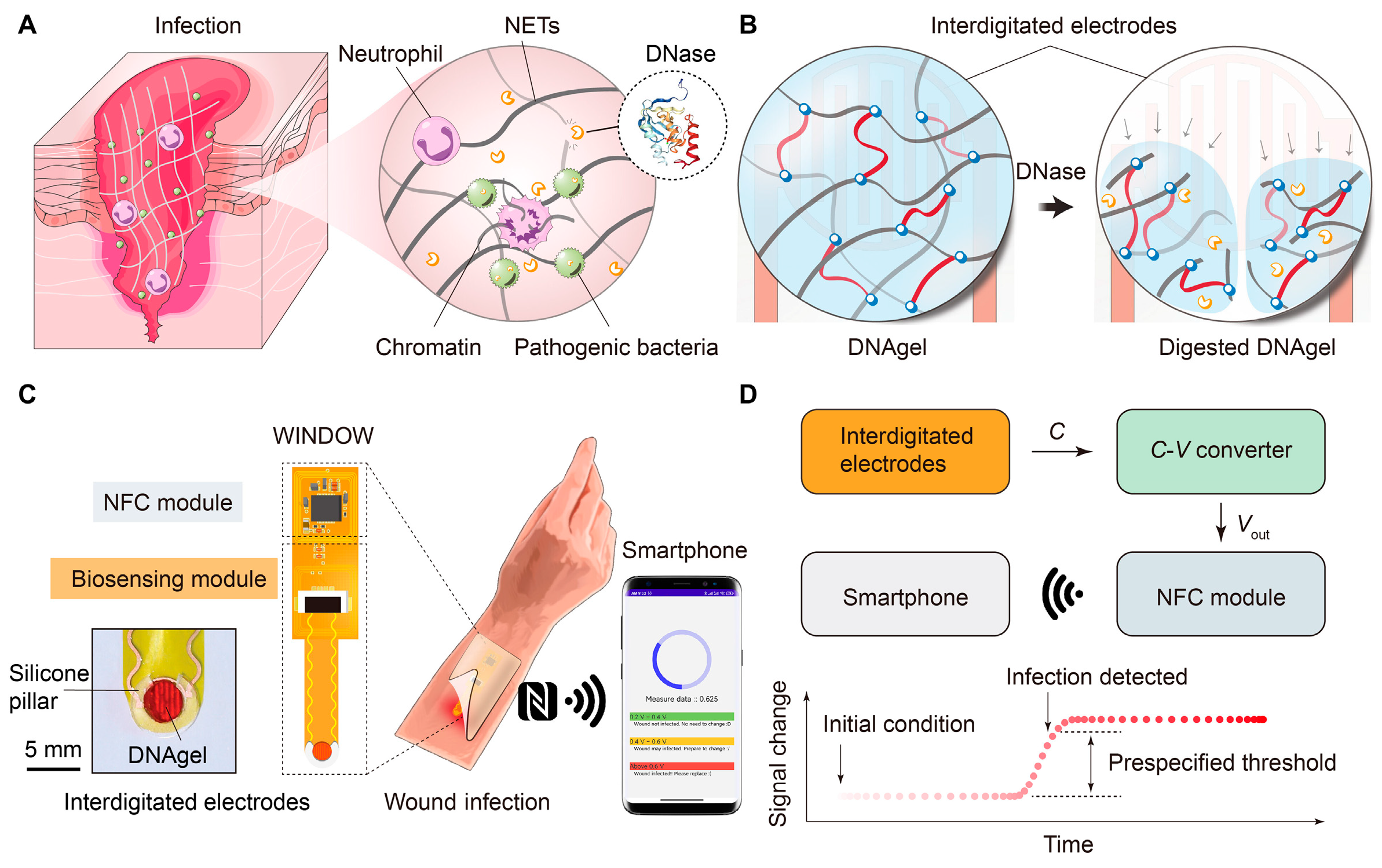

- Xiong, Z.; Achavananthadith, S.; Lian, S.; Madden, L.E.; Ong, Z.X.; Chua, W.; Kalidasan, V.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Singh, P.; et al. A wireless and battery-free wound infection sensor based on DNA hydrogel. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

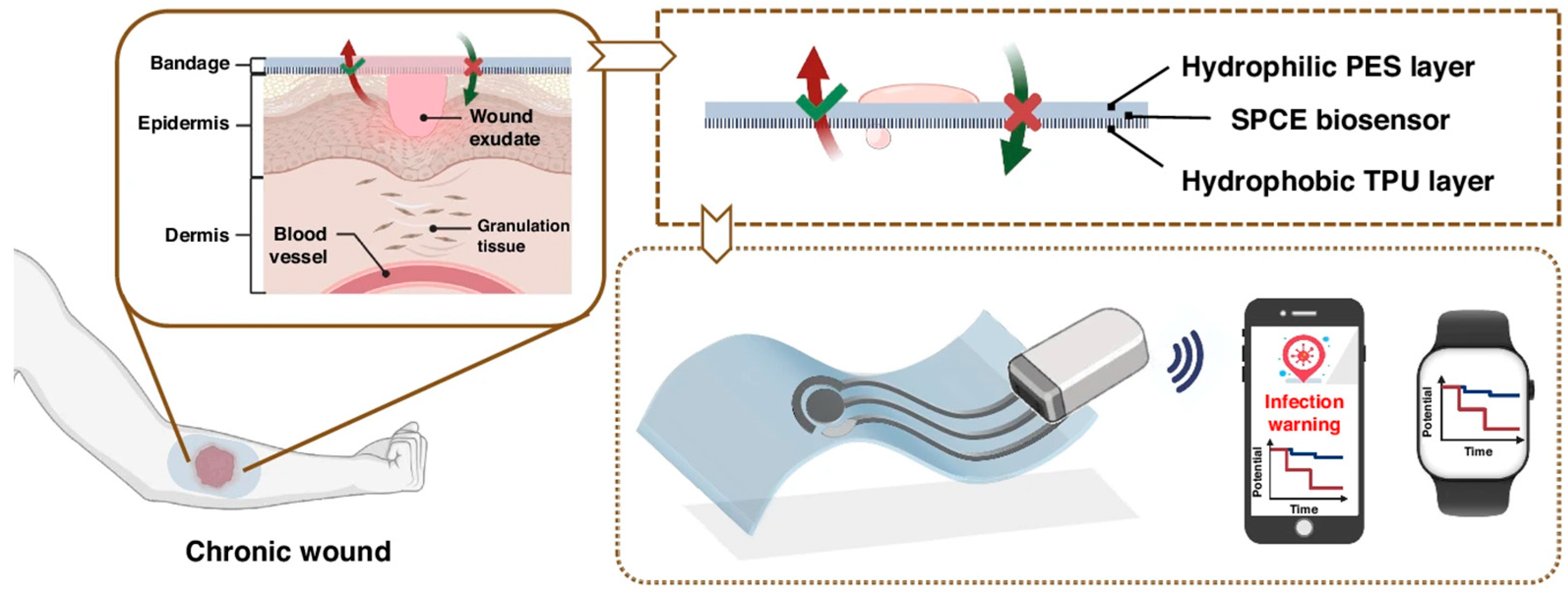

- Yu, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Seidi, F.; Deng, C. Antibacterial and biodegradable bandage with exudate absorption and smart monitoring for chronic wound management. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2025, 10, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yang, S.; Liu, C.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X. Integrated Wound Recognition in Bandages for Intelligent Treatment. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, e2000941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, H. Chronic wound management: A liquid diode-based smart bandage with ultrasensitive pH sensing ability. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ye, J.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, C.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X. An Integrated Janus Bioelectronic Bandage for Unidirectional Pumping and Monitoring of Wound Exudate. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 5156–5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jeong, J.W. Recent Advances in Skin-Mounted Electronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2025, 11, e2500316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Huang, S.; Guo, B. Chitosan-based self-healing hydrogel dressing for wound healing. Adv. Colloid. Interfac. 2024, 332, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.Y.; Chen, X.J.; Hong, Z.P.; Zhang, L.Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, J.W.; Rong, M.Z.; Zhang, M.Q. Repeatedly Intrinsic Self-Healing of Millimeter-Scale Wounds in Polymer through Rapid Volume Expansion Aided Host–Guest Interaction. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 22534–22542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Injectable Conductive Hydrogel with Self-Healing, Motion Monitoring, and Bacteria Theranostics for Bioelectronic Wound Dressing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2303876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Li, G.; Yan, D.; Liu, C.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X. Ultra-Small Wearable Flexible Biosensor for Continuous Sweat Analysis. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 3102–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, B.; Huang, J.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, G. A molecular imprinting photoelectrochemical sensor modified by polymer brushes and its detection for BSA. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, B.; Liu, X. Intramicellar sensor assays: Improving sensing sensitivity of sensor array for thiol biomarkers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 273, 117173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas Domínguez, R.A.; Águila Rosas, J.; Martínez Tolibia, S.E.; Lima, E.; Dutt, A. Opportunities in functionalized metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with open metal sites for optical biosensor application. Adv. Colloid. Interfac. 2025, 344, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Miao, J.; Zhang, C.; Cui, D. High-Sensitive Wearable Strain Sensors Based on the Carbon Nanotubes@Porous Soft Silicone Elastomer with Excellent Stretchability, Durability, and Biocompatibility. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 51373–51383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, M.A.; Naghib, S.M.; Rabiee, N. Smart biosensors with self-healing materials. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 8653–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Song, S. Ultra-stretchable, adhesive, fatigue resistance, and anti-freezing conductive hydrogel based on gelatin/guar gum and liquid metal for dual-sensory flexible sensor and all-in-one supercapacitors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantseva, E.; Bonaccorso, F.; Feng, X.; Cui, Y.; Gogotsi, Y. Energy storage: The future enabled by nanomaterials. Science 2019, 366, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Abidian, M. Organic Bioelectronics. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2404458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchordoquy, T.; Artzi, N.; Balyasnikova, I.V.; Barenholz, Y.; La-Beck, N.M.; Brenner, J.S.; Chan, W.C.W.; Decuzzi, P.; Exner, A.A.; Gabizon, A.; et al. Mechanisms and Barriers in Nanomedicine: Progress in the Field and Future Directions. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 13983–13999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Zarei, M.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.G. Wearable Standalone Sensing Systems for Smart Agriculture. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2414748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, G.; Mastronardi, V.M.; Todaro, M.T.; Blasi, L.; Antonaci, V.; Algieri, L.; Scaraggi, M.; De Vittorio, M. Sustainable electronic biomaterials for body-compliant devices: Challenges and perspectives for wearable bio-mechanical sensors and body energy harvesters. Nano Energy 2024, 123, 109336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoum, A.; Sadak, O.; Ramirez, I.A.; Iverson, N. Stimuli-bioresponsive hydrogels as new generation materials for implantable, wearable, and disposable biosensors for medical diagnostics: Principles, opportunities, and challenges. Adv. Colloid. Interfac. 2023, 317, 102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewpradub, K.; Veenuttranon, K.; Jantapaso, H.; Mittraparp-arthorn, P.; Jeerapan, I. A Fully-Printed Wearable Bandage-Based Electrochemical Sensor with pH Correction for Wound Infection Monitoring. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, Z.; Fu, S.-T.; Yang, C.-J.; Yin, Y.-Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, C.-Q.; Qiao, H.; Ji, D.-K. Mitochondria-Targeted Dual-Ion Perturbator Amplifies Cuproptosis for Enhanced Melanoma Immunotherapy and Accelerated Postoperative Wound Healing. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 37544–37560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Wei, J.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Liao, X. Highly sensitive electrochemical biosensor for MMP-2 detection using multi-stage amplification with PNA T7 RNA polymerase and split CRISPR/Cas12a. Microchem. J. 2025, 208, 112506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B.; Hu, Z.; Li, T.; Ma, X.; Jiang, C.; Zou, H.; Liu, S.; et al. Soft bioelectronics embedded with self-confined tetrahedral DNA circuit for high-fidelity chronic wound monitoring. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lillehoj, P.B. Embroidered electrochemical sensors on gauze for rapid quantification of wound biomarkers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 98, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Mei, Z.; Shen, Q.; Liao, K.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, L. Advances in cellulose-based self-powered ammonia sensors. Carbohyd. Polym. 2025, 351, 123074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, M.; Rafiee, Z.; Choi, S. Unlocking Wearable Microbial Fuel Cells for Advanced Wound Infection Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 36117–36130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Huang, H.; Sun, C.; Yu, J.; Wang, M.; Dong, T.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Cui, T.; Li, J. Flexible Accelerated-Wound-Healing Antibacterial Hydrogel-Nanofiber Scaffold for Intelligent Wearable Health Monitoring. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 16, 5438–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gascon-Y-Marin, I.; Mir, M.; Santiago, A.; Foncillas-Garcia, M.A.; Osorio, T.; Ruiz-Gomez, F.-J.; Solaeta, M.J.; Diez, V.; Suarez-Liceras, N.; Bibiano-Guillen, C.; et al. pb2687 digital-health and remote monitoring for patients receiving. HemaSphere 2023, 7, e77078d5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biological Markers | Detection Ranges | Reference Values for Health Status | Abnormal Threshold/Clinical Significance | Multi-Parameter Interlocking Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 25–40 °C (Sensor range) | 31.1–36.5 °C (Recovery of normal wound) | Below normal: ↓ 2.2 °C → Blood circulation disorder/Enzyme activity reduction/Lymphocyte decrease Above normal: ↑ 2.2 °C → Infection/Severe inflammation | Linked pH compensation for detecting errors |

| pH | 4.0–9.0 (CW-care) 5–10 (e-ECM) | 4.0–6.5 (Healthy skin/Acute wounds) | >7.0: Markers of chronic wound alkalization >10.0: Severe infection (such as alkaline-producing bacteria/MRSA biofilm) Pathological mechanism: Ischemia-reperfusion injury → Bacterial proliferation | Regulation of collagen synthesis/angiogenesis/pathogen inhibition |

| Uric acid (UA) | 0–150 μM (CW-care) | 220–750 μM (No infection status) | <200 μM: Indicator of bacterial infection | Different from the specific infection indicators of endogenous metabolism |

| Glucose | 0–40 mM (CW-care) 0–8 mM (e-ECM) | Diabetic wound fluctuations: 0–1.2 mM | Hyperglycemia: Inhibits HIF-1α → Promotes angiogenesis; Facilitates tissue necrosis; Bacterial proliferation | The core metabolic indicators for the prognosis of diabetic wounds |

| Lactic acid | 0–4 mM (CW-care) 0–30 mM (e-ECM) | - | Continuity: Oxygen deprivation metabolic markers; Association with inflammation severity | Concurrently assess tissue hypoxia with oxygen |

| Na+ | 133–146 mM | - | Imbalance: Disruption of interstitial fluid osmotic pressure → Delayed healing | Reflecting the homeostasis of the wound microenvironment |

| K+ | 3.2–5.7 mM | - | Imbalance: Abnormal cell membrane potential → Restoration of cell function | Reflect the metabolic state of cells |

| Dissolved oxygen | 0–3.35 mL/L (e-ECM) | - | Low oxygen: Vascularization/Collagen deposition ↓; Macrophage recruitment is blocked High oxygen: Guided oxygen therapy intervention | Linking with ROS to evaluate oxidative stress |

| ROS | - | - | Upregulation-Marker of infection and chronic inflammation; Strongly associated with impaired healing | Sensitive indicators preceding clinical infection |

| Microbial metabolites | - | - | Specific markers: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pyocyanin; Staphylococcus aureus: Phospholipase A2/α-hemolysin | Pathogen typing and targeted therapy basis |

| Application Domain | Sensing Principle | Fundamental Advantages | Inherent Limitations | Clinical Adaptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection Diagnosis | Specific biorecognition mechanisms (enzyme-substrate or antigen-antibody binding) | High pathogen targeting and molecular resolution capability | Bioprobe degradation and coexisting interferents | In vivo validation is needed to address complex matrix effects |

| Inflammation Monitoring | Immunoelectrochemical methods (labeled or label-free binding detection) | Multiplex compatibility and ultrasensitivity | Antibody instability and narrow dynamic range | Requires validation through in vivo inflammation models |

| Metabolite Analysis | Enzymatic catalysis or direct oxidation of electroactive species | Direct metabolic pathway mapping and real-time tracking | Enzyme denaturation and electroactive interference | Necessitates continuous in vivo monitoring |

| Wound Environment Tracking | Physicochemical signal conversion via electrical changes (potential/resistance/capacitance) | Wide linear range and continuous parameter monitoring | Sensor drift and mechanical stress sensitivity | Requires long-term in vivo stability verification |

| Therapeutic Feedback Control | Closed-loop sensing-actuation coupling triggering therapeutic delivery | Integrated diagnosis-therapy systems and adaptive intervention | System latency and limited drug payload capacity | Mandates in vivo therapeutic efficacy validation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zuo, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.-J. Wearable Electrochemical Biosensors for Monitoring and Management of Chronic Wounds. Biosensors 2025, 15, 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120785

Zuo L, Liu Y, Zhang J, Wang L, Zhu J-J. Wearable Electrochemical Biosensors for Monitoring and Management of Chronic Wounds. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120785

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuo, Lingxia, Yinbing Liu, Jianrong Zhang, Linlin Wang, and Jun-Jie Zhu. 2025. "Wearable Electrochemical Biosensors for Monitoring and Management of Chronic Wounds" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120785

APA StyleZuo, L., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Wang, L., & Zhu, J.-J. (2025). Wearable Electrochemical Biosensors for Monitoring and Management of Chronic Wounds. Biosensors, 15(12), 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120785