Effects of Disinfectant Solutions Against COVID-19 on Surface Roughness, Gloss, and Color of Removable Denture Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Materials

2.2. Disinfection Protocol

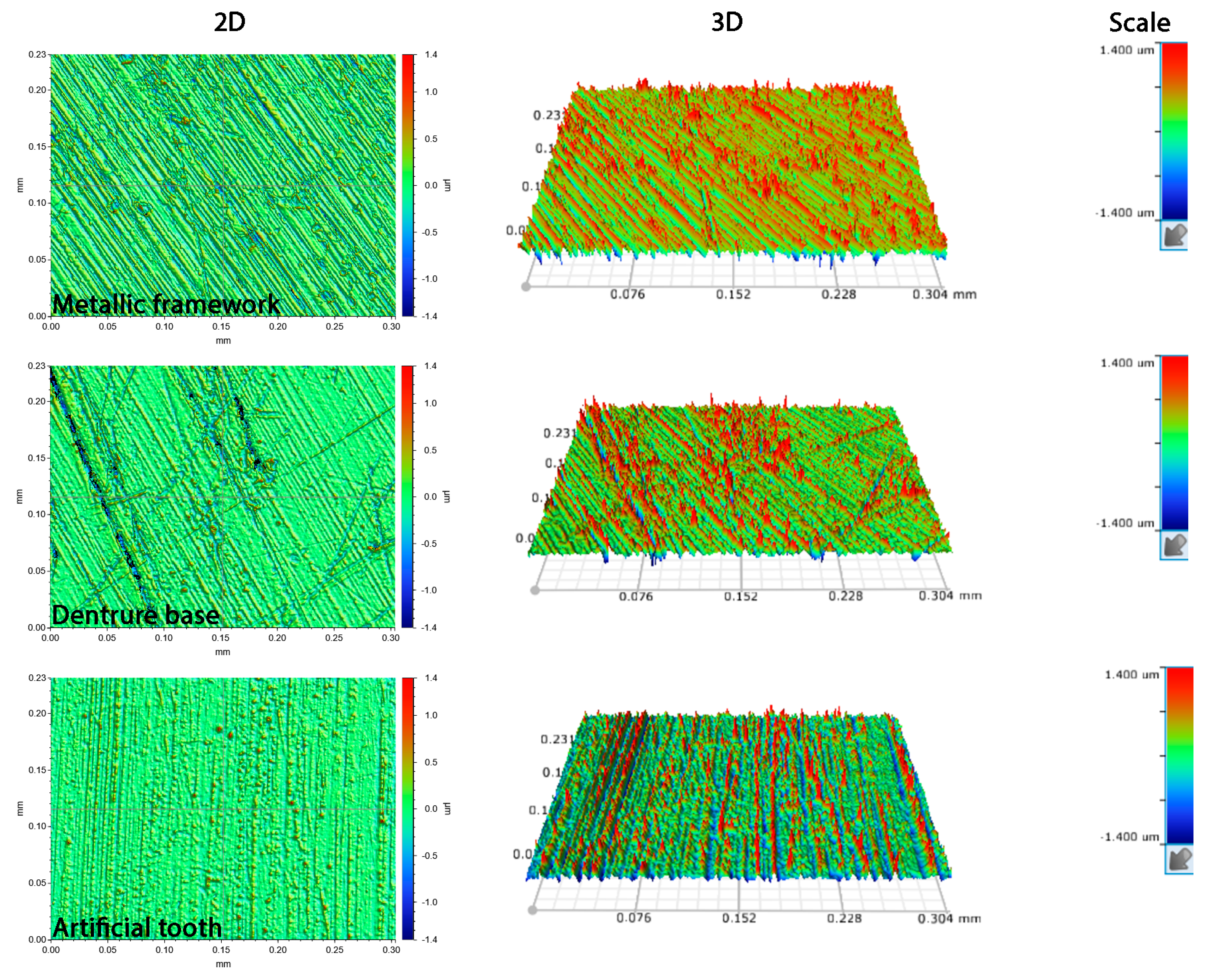

2.3. Surface Roughness Measurements

2.4. Gloss Measurements

2.5. Color Measurements

2.6. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Surface Roughness

3.2. Gloss

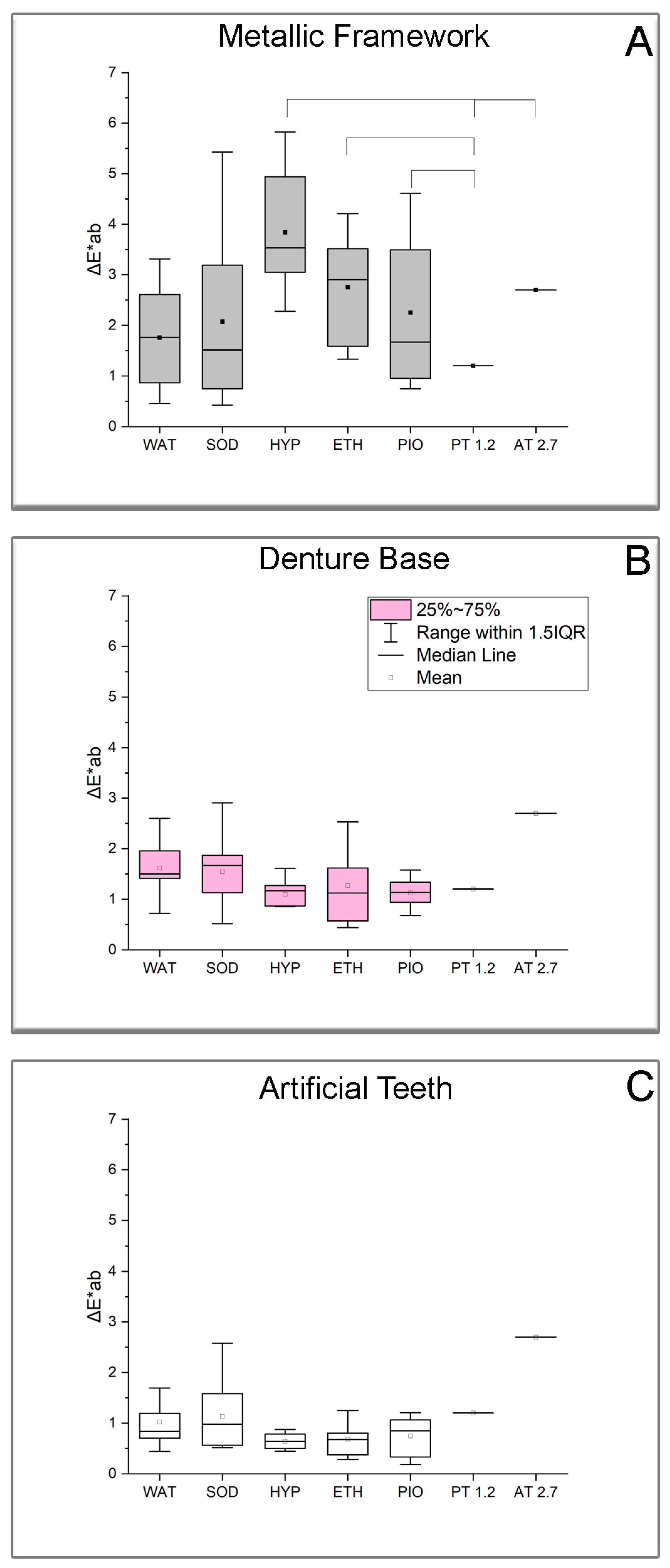

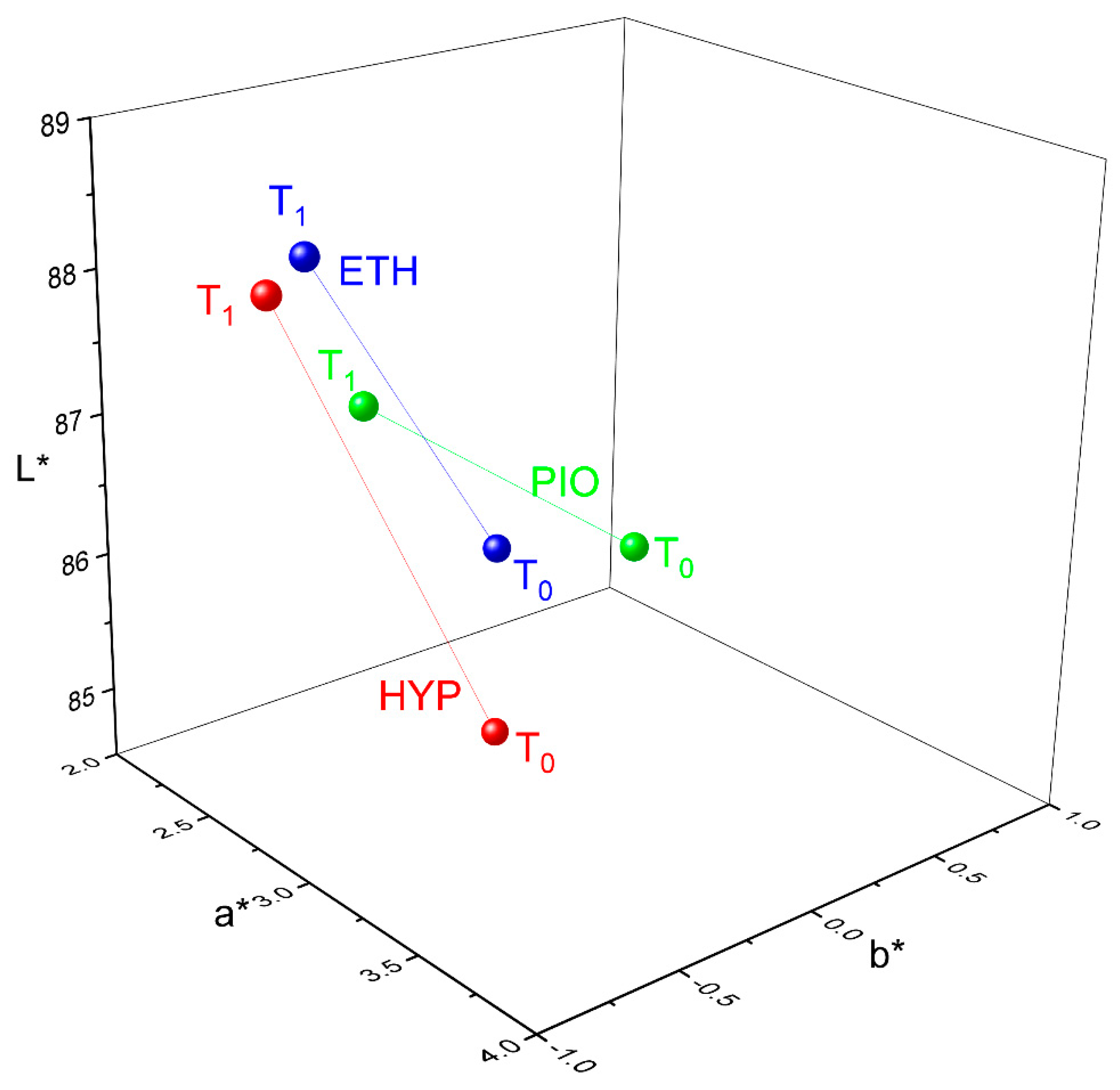

3.3. Color Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The roughness of the denture material tested was not affected by the tested disinfectants.

- The use of disinfectants had a positive effect on the gloss of all materials tested.

- All materials tested demonstrated substantial color stability after disinfections except the Co-Cr alloy with hydrogen peroxide, and from this standpoint, the use of H2O2 should be avoided.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Number of COVID-19 Deaths Reported to WHO (Cumulative Total); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, N.; Siddaiah, A.; Joseph, B. Tackling Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID 19) in Workplaces. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 24, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzrodt, C.L.; Maknojia, I.; McCarthy, R.D.P.; Oldfield, T.M.; Po, J.; Ta, K.T.L.; Stepp, H.E.; Clements, T.P. A Guide to COVID-19: A global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3633–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.; Domingo, J.L. Contamination of inert surfaces by SARS-CoV-2: Persistence, stability and infectivity. A review. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, A.M.; Miyoshi, P.R.; Gnoatto, N.; Paranhos, H.d.F.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Salvador, S.L. Cross-contamination in the dental laboratory through the polishing procedure of complete dentures. Braz. Dent. J. 2004, 15, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G.; Todt, D.; Pfaender, S.; Steinmann, E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fu, B. Effects of disinfectants on physical properties of denture base resins: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 131, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, A.C.; Matilde Fdos, S.; Rosa, F.C.; Kimpara, E.T.; Jorge, A.O.; Balducci, I.; Koga-Ito, C.Y. Disinfection protocols to prevent cross-contamination between dental offices and prosthetic laboratories. J. Infect. Public Health 2013, 6, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintze, S.D.; Forjanic, M.; Ohmiti, K.; Rousson, V. Surface deterioration of dental materials after simulated toothbrushing in relation to brushing time and load. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ereifej, N.S.; Oweis, Y.G.; Eliades, G. The effect of polishing technique on 3-D surface roughness and gloss of dental restorative resin composites. Oper. Dent. 2013, 38, E1–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunz, O.; Diekamp, M.; Bizhang, M.; Testrich, H.; Piwowarczyk, A. Surface roughness associated with bacterial adhesion on dental resin-based materials. Dent. Mater. J. 2024, 43, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, L.C.; da Silva-Neto, J.P.; Dantas, T.S.; Naves, L.Z.; das Neves, F.D.; da Mota, A.S. Bacterial Adhesion and Surface Roughness for Different Clinical Techniques for Acrylic Polymethyl Methacrylate. Int. J. Dent. 2016, 2016, 8685796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, C.M.; Lambrechts, P.; Quirynen, M. Comparison of surface roughness of oral hard materials to the threshold surface roughness for bacterial plaque retention: A review of the literature. Dent. Mater. 1997, 13, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda-Navarro, W.F.; Arana-Correa, B.E.; Borges, C.P.; Jorge, J.H.; Urban, V.M.; Campanha, N.H. Color stability of resins and nylon as denture base material in beverages. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyf, F.; Etikan, I. Evaluation of gloss changes of two denture acrylic resin materials in four different beverages. Dent. Mater. 2004, 20, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Johnson, G.H.; Gordon, G.E. Effects of chemical disinfectants on the surface characteristics and color of denture resins. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1997, 77, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipucci, D.N.; Davi, L.R.; Paranhos, H.F.; Bezzon, O.L.; Silva, R.F.; Pagnano, V.O. Effect of different cleansers on the surface of removable partial denture. Braz. Dent. J. 2011, 22, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranhos, H.d.F.; Peracini, A.; Pisani, M.X.; Oliveira, V.d.C.; de Souza, R.F.; Silva-Lovato, C.H. Color stability, surface roughness and flexural strength of an acrylic resin submitted to simulated overnight immersion in denture cleansers. Braz. Dent. J. 2013, 24, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, E.A.; Altintas, S.H.; Turgut, S. Effects of cigarette smoke and denture cleaners on the surface roughness and color stability of different denture teeth. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, G.L.L.; Curylofo, P.A.; Raile, P.N.; Macedo, A.P.; Paranhos, H.F.O.; Pagnano, V.O. Effect of Alkaline Peroxides on the Surface of Cobalt Chrome Alloy: An In Vitro Study. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, e337–e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curylofo, P.A.; Raile, P.N.; Vasconcellos, G.L.L.; Macedo, A.P.; Pagnano, V.O. Effect of Denture Cleansers on Cobalt-Chromium Alloy Surface: A Simulated Period of 5 Years’ Use. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitencourt, S.B.; Catanoze, I.A.; da Silva, E.V.F.; Dos Santos, P.H.; Dos Santos, D.M.; Turcio, K.H.L.; Guiotti, A.M. Effect of acidic beverages on surface roughness and color stability of artificial teeth and acrylic resin. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2020, 12, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHamdan, E.M.; Al-Saleh, S.; Nisar, S.S.; Alshiddi, I.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Alzahrani, K.M.; Naseem, M.; Vohra, F.; Abduljabbar, T. Efficacy of porphyrin derivative, Chlorhexidine and PDT in the surface disinfection and roughness of Cobalt chromium alloy removable partial dentures. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 36, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakis, G.S.; Kapczinski, M.P.; Fraga, S.; Mengatto, C.M. Effects of disinfection with a vinegar-hydrogen peroxide mixture on the surface composition and topography of a cobalt-chromium alloy. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 132, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timbo, I.C.G.; Oliveira, M.; Regis, R.R. Effect of sanitizing solutions on cobalt-chromium alloys for dental prostheses: A systematic review of in vitro studies. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 132, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, I.; Papavasiliou, G.; Kamposiora, P.; Zoidis, P. Effect of Staining Solutions on Color Stability, Gloss and Surface Roughness of Removable Partial Dental Prosthetic Polymers. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakmak, G.; Donmez, M.B.; Akay, C.; Atalay, S.; Silva de Paula, M.; Schimmel, M.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of simulated brushing and disinfection on the surface roughness and color stability of CAD-CAM denture base materials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 134, 105390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, L.O.; Campos, D.E.S.; da Nobrega Alves, D.; Carreiro, A.; de Castro, R.D.; Batista, A.U.D. Effects of long-term cinnamaldehyde immersion on the surface roughness and color of heat-polymerized denture base resin. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 521.e1–521.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, A.; Machado, A.L.; Vergani, C.E.; Giampaolo, E.T.; Pavarina, A.C.; Magnani, R. Effect of disinfectants on the hardness and roughness of reline acrylic resins. J. Prosthodont. 2006, 15, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, Ş.T.; Özkan, P. Evaluation of Different Beverages’ Effect on Microhardness and Surface Roughness of Different Artificial Teeth. Eur. Ann. Dent. Sci. 2021, 48, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzugullu, B.; Acar, O.; Cetinsahin, C.; Celik, C. Effect of different denture cleansers on surface roughness and microhardness of artificial denture teeth. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2016, 8, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davi, L.R.; Peracini, A.; de Queiroz Ribeiro, N.; Soares, R.B.; Da Silva, C.H.L.; de Freitas Oliveira Paranhos, H.; De Souza, R.F. Effect of the physical properties of acrylic resin of overnight immersion in sodium hypochlorite solution. Gerodontology 2010, 27, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.M.; Acosta, E.J.; Jacobina, M.; Pinto, L.d.R.; Porto, V.C. Effect of repeated immersion solution cycles on the color stability of denture tooth acrylic resins. J. Appl. Oral. Sci. 2011, 19, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskin, B.; Sipahi, C.; Akin, H. Effect of different chemical disinfectants on color stability of acrylic denture teeth. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 23, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, T.S.; Aguilar, F.G.; Garcia, L.d.F.; Pires-de-Souza, F.d.C. Colour stability of denture teeth submitted to different cleaning protocols and accelerated artificial aging. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2014, 22, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtulmus-Yilmaz, S.; Deniz, S.T. Evaluation of staining susceptibility of resin artificial teeth and stain removal efficacy of denture cleansers. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2014, 72, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, A.; Powers, J.M.; Kiat-Amnuay, S. Color stability of denture teeth and acrylic base resin subjected daily to various consumer cleansers. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2014, 26, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Polychronakis, N.C.; Polyzois, G.L.; Lagouvardos, P.E.; Papadopoulos, T.D. Effects of cleansing methods on 3-D surface roughness, gloss and color of a polyamide denture base material. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2015, 73, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qarni, F.D.; Goodacre, C.J.; Kattadiyil, M.T.; Baba, N.Z.; Paravina, R.D. Stainability of acrylic resin materials used in CAD-CAM and conventional complete dentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 123, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motayagheni, R.; Ebrahim Adhami, Z.; Taghizadeh Motlagh, S.M.; Mehrara, F.; Yasamineh, N. Color changes of three different brands of acrylic teeth in removable dentures in three different beverages: An in vitro study. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2020, 14, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, M.; Sadighpour, L.; Geramipanah, F.; Ehsani, A.; Shahabi, S. Color Stability of Different Denture Teeth Following Immersion in Staining Solutions. Front. Dent. 2022, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyzois, G.; Niarchou, A.; Ntala, P.; Pantopoulos, A.; Frangou, M. The effect of immersion cleansers on gloss, colour and sorption of acetal denture base material. Gerodontology 2013, 30, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, A.; Alexandrino, L.D.; Santos, V.R.D.; Kapczinski, M.P.; Fraga, S.; Silva, W.J.D.; Mengatto, C.M. Effect of a vinegar-hydrogen peroxide mixture on the surface properties of a cobalt-chromium alloy: A possible disinfectant for removable partial dentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polychronakis, N.; Mikeli, A.; Lagouvardos, P.; Polyzois, G. Effects of Disinfectants Used for COVID-19 Protection on the Color and Translucency of Acrylic Denture Teeth. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarb, G.; Bolender, C. Prosthodontic Treatment for Edentulous Patients: Complete Dentures and Implant-Supported Prostheses, 12th ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sadr, K.; Mahboob, F.; Rikhtegar, E. Frequency of Traumatic Ulcerations and Post-insertion Adjustment Recall Visits in Complete Denture Patients in an Iranian Faculty of Dentistry. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2011, 5, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Felton, D.; Cooper, L.; Duqum, I.; Minsley, G.; Guckes, A.; Haug, S.; Meredith, P.; Solie, C.; Avery, D.; Chandler, N.D.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the care and maintenance of complete dentures: A publication of the American College of Prosthodontists. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 20, S1–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswati, S.; Razdan, P.; Smita Aggarwal, M.; Bhowmick, D.; Priyadarshni, P. Traumatic Ulcerations Frequencies and Postinsertion Adjustment Appointments in Complete Denture Patients. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13, S1375–S1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Masood, M.; Mnatzaganian, G. Complete denture replacement: A 20-year retrospective study of adults receiving publicly funded dental care. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2022, 66, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D532-14; Standard Test Method for Specular Gloss. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5.

- ISO 2813; Paint and Varnishes-Measurements of Specular Gloss of Nonmetallic Paint Films at 20°, 60°, and 85. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO/TR 28642; Dentistry-Guidance on Color Measurement. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–18.

- Heintze, S.D.; Forjanic, M.; Rousson, V. Surface roughness and gloss of dental materials as a function of force and polishing time in vitro. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, J.; Fauxpoint, G.; Arntz, Y.; Pelletier, H.; Etienne, O. Surface roughness and morphology of three nanocomposites after two different polishing treatments by a multitechnique approach. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakaboura, A.; Fragouli, M.; Rahiotis, C.; Silikas, N. Evaluation of surface characteristics of dental composites using profilometry, scanning electron, atomic force microscopy and gloss-meter. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2007, 18, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelmawla, E.; Koura, M.; Maksoud, T.; Elewa, I.; Soliman, H. Roughness parameter. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2002, 123, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 25178-2:2021; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Areal. Part 2: Terms, Definitions and Surface Texture Parameters. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Park, J.B.; Jeon, Y.; Ko, Y. Effects of titanium brush on machined and sand-blasted/acid-etched titanium disc using confocal microscopy and contact profilometry. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.C.; Bahia, M.G.; Buono, V.T. Surface analysis of ProFile instruments by scanning electron microscopy and X-ray energy-dispersive spectroscopy: A preliminary study. Int. Endod. J. 2002, 35, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Polo, C.; Montero, J.; Gomez-Polo, M.; Martin Casado, A. Comparison of the CIELab and CIEDE 2000 Color Difference Formulas on Gingival Color Space. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disinfectant Solutions | Concentration (wt%) | pH | Immersion Regime | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distilled H2O | 6.8 | 15 min 1 | WAT | |

| Sodium Hypochlorite NaOCl | 0.1 | 7.5 | 15 × 1 min = 15 min | SOD |

| Hydrogen Peroxide H2O2 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 15 × 1 min = 15 min | HYP |

| Ethanol C2H6O | 78 | 6.8 | 15 × 0.5 min = 7.5 | ETH |

| Povidone iodine (C6H9I2NO) | 1 | 5.7 | 15 × 1 min = 15 min | PIO |

| Metallic Framework | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Sa (nm) | Sq (nm) | Sz (nm) | Sc (nm) | Sv (nm) | |||||

| T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | |

| WAT | 144 (14) | 152 (21) | 190 (19) | 197 (24) | 3256 (1850) | 2953 (860) | 188 (24) | 201 (35) | 25 (2) | 26 (2) |

| SOD | 132 (21) | 131 (20) | 175 (27) | 173 (20) | 3256 (1237) | 2652 (540) | 171 (39) | 171 (28) | 23 (2) | 24 (2) |

| HYP | 117 (17) | 118 (28) | 157 (19) | 161 (32) | 2760 (924) | 3508 (1388) | 142 (30) | 147 (38) | 22 (1) | 24 (4) |

| ETH | 128 (25) | 144 (21) | 174 (33) | 190 (22) | 3922 (1999) | 3095 (1227) | 166 (42) | 186 (38) | 24 (2) | 26 (1) |

| PIO | 127 (16) | 136 (22) | 167 (20) | 178 (28) | 2599 (443) | 2777 (399) | 166 (30) | 175 (32) | 22 (1) | 23 (2) |

| Denture Base | ||||||||||

| WAT | 112 (25) | 94 (3) | 158 (51) | 172 (41) | 4463 (1326) | 5083 (2062) | 167 (38) | 130 (47) | 22 (7) | 24 (8) |

| SOD | 113 (30) | 100 (33) | 185 (50) | 162 (35) | 5365 (2220) | 5468 (2048) | 160 (45) | 145 (49) | 26 (6) | 23 (6) |

| HYP | 106 (57) | 106 (37) | 184 (97) | 170 (62) | 6888 (5423) | 5486 (3928) | 153 (84) | 147 (55) | 25 (15) | 25 (8) |

| ETH | 118 (53) | 122 (44) | 185 (79) | 191 (60) | 6618 (3042) | 5908 (2089) | 169 (79) | 175 (68) | 26 (12) | 28 (9) |

| PIO | 121 (69) | 140 (97) | 192 (90) | 176 (45) | 7937 (3906) | 7132 (4523) | 174 (95) | 193 (133) | 23 (8) | 27 (7) |

| Artificial Teeth | ||||||||||

| WAT | 48 (28) | 73 (17) | 75 (43) | 116 (33) | 2322 (650) | 2882 (680) | 74 (42) | 109 (26) | 6 (3) | 9 (1) |

| SOD | 70 (11) | 79 (13) | 109 (20) | 120 (20) | 3086 (1211) | 3590 (1438) | 108 (22) | 122 (26) | 10 (1) | 11 (1) |

| HYP | 70 (10) | 77 (11) | 105 (16) | 118 (19) | 2383 (427) | 2325 (453) | 107 (17) | 118 (20) | 9 (1) | 11 (1) |

| ETH | 68 (18) | 72 (9) | 109 (30) | 106 (14) | 2483 (785) | 2582 (692) | 100 (29) | 106 (14) | 10 (2) | 11 (1) |

| PIO | 75 (10) | 80 (14) | 115 (14) | 118 (21) | 3137 (955) | 2608 (638) | 115 (19) | 122 (24) | 10 (1) | 12 (2) |

| Metallic Framework | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | T0 | T1 | p | ΔG |

| WAT | 230 (15) | 233 (14) | <0.001 | 2.6 [1.4–4.8] A |

| SOD | 297 [259–309] | 308 [301–327] | 0.002 | 14.1 [3.8–44.5] AB |

| HYP | 260 [239–287] | 306 [285–327] | 0.002 | 39.7 [28.0–67.8] B |

| ETH | 252 (44) | 296 (38) | <0.001 | 37.0 [29.9–62.5] B |

| PIO | 280 (41) | 307 (46) | 0.003 | 26.7 [4.9–43.2] AB |

| Denture Base | ||||

| WAT | 95 (12) | 103 (7) | 0.004 | 7.1 [2.3–11.4] A |

| SOD | 97 (6) | 105 (10) | 0.009 | 9.4 [1.1–13.7] A |

| HYP | 96 [79–104] | 103 [86–109] | 0.002 | 2.4 [0.7–9.2] A |

| ETH | 86 [82–101] | 89 [84–110] | 0.002 | 1.2 [0.5–5.4] A |

| PIO | 93 [78–99] | 97 [81–107] | 0.002 | 2.6 [1.0–6.9] A |

| Artificial Teeth | ||||

| WAT | 12 (2) | 26 (5) | <0.001 | 13.9 (4.8) AB |

| SOD | 10 (1) | 28 (5) | <0.001 | 17.9 (6.4) B |

| HYP | 10 (2) | 20 (3) | <0.001 | 10.0 (4.1) A |

| ETH | 12 (1) | 22 (4) | <0.001 | 9.8 (4.5) A |

| PIO | 11 (1) | 22 (5) | <0.001 | 10.8 (6.1) A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mikeli, A.; Polychronakis, N.; Barmpagadaki, X.; Polyzois, G.; Lagouvardos, P.; Zinelis, S. Effects of Disinfectant Solutions Against COVID-19 on Surface Roughness, Gloss, and Color of Removable Denture Materials. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120446

Mikeli A, Polychronakis N, Barmpagadaki X, Polyzois G, Lagouvardos P, Zinelis S. Effects of Disinfectant Solutions Against COVID-19 on Surface Roughness, Gloss, and Color of Removable Denture Materials. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(12):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120446

Chicago/Turabian StyleMikeli, Aikaterini, Nick Polychronakis, Xanthippi Barmpagadaki, Gregory Polyzois, Panagiotis Lagouvardos, and Spiros Zinelis. 2025. "Effects of Disinfectant Solutions Against COVID-19 on Surface Roughness, Gloss, and Color of Removable Denture Materials" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 12: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120446

APA StyleMikeli, A., Polychronakis, N., Barmpagadaki, X., Polyzois, G., Lagouvardos, P., & Zinelis, S. (2025). Effects of Disinfectant Solutions Against COVID-19 on Surface Roughness, Gloss, and Color of Removable Denture Materials. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(12), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120446