Flexural Strength and Hardness Analysis of 3D-Printed vs. Milled Resin Composites Indicated for Definitive Crowns

Abstract

1. Introduction

- There is no significant difference in the mechanical properties of the investigated materials between the 3D-printed and milled resin composites indicated for definitive crowns.

- The composition of the evaluated materials does not affect their mechanical properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Specimen Preparation

2.2.1. Milled Resin Composite Blocks

2.2.2. 3D-Printed Resin Composites

2.3. Evaluation of Filler Content

2.4. Evaluation of the Flexural Strength

2.5. Evaluation of the Hardness

2.5.1. Martens Hardness

2.5.2. Vickers Hardness

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Filler Content

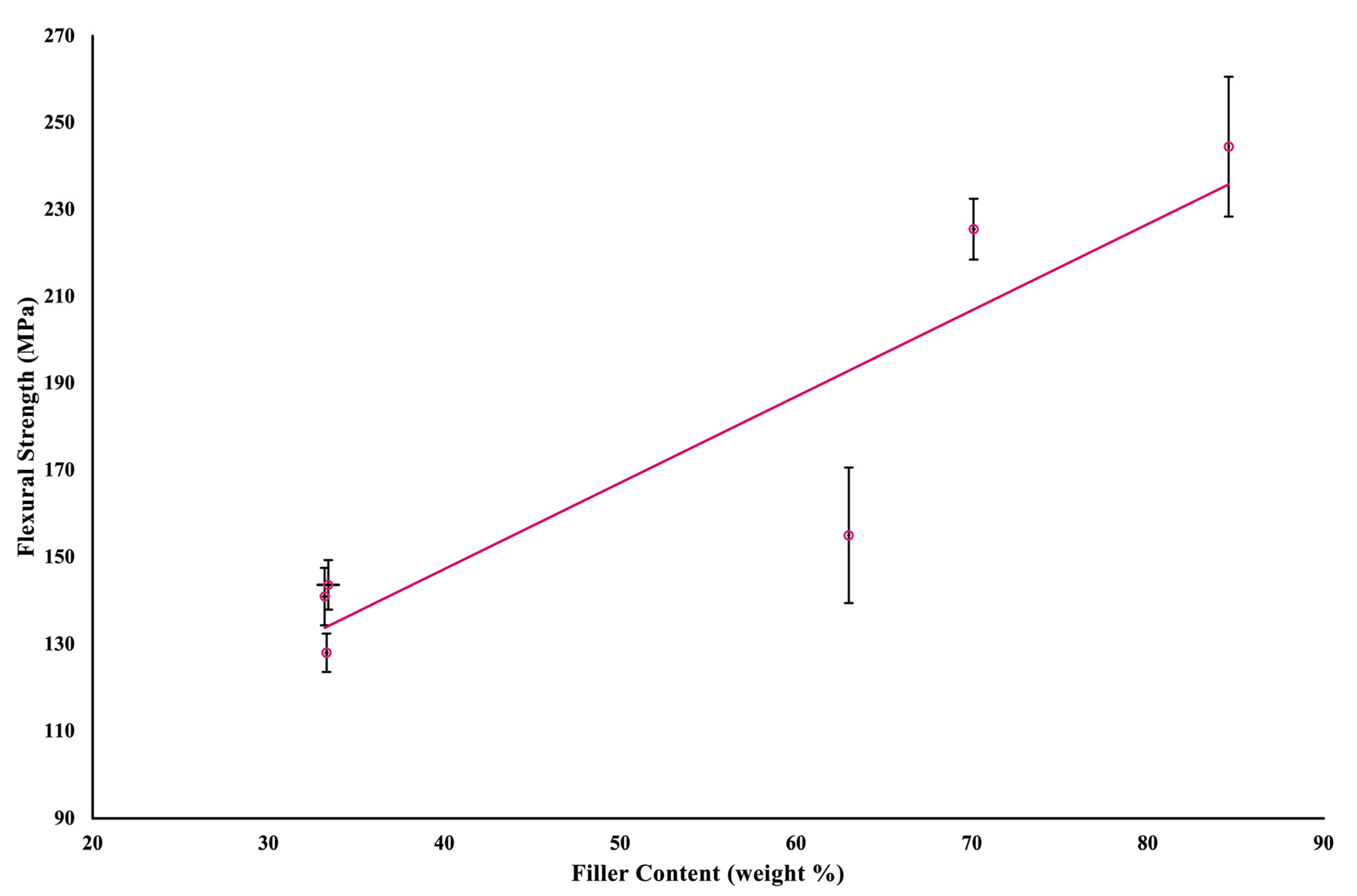

3.2. Flexural Strength and Modulus

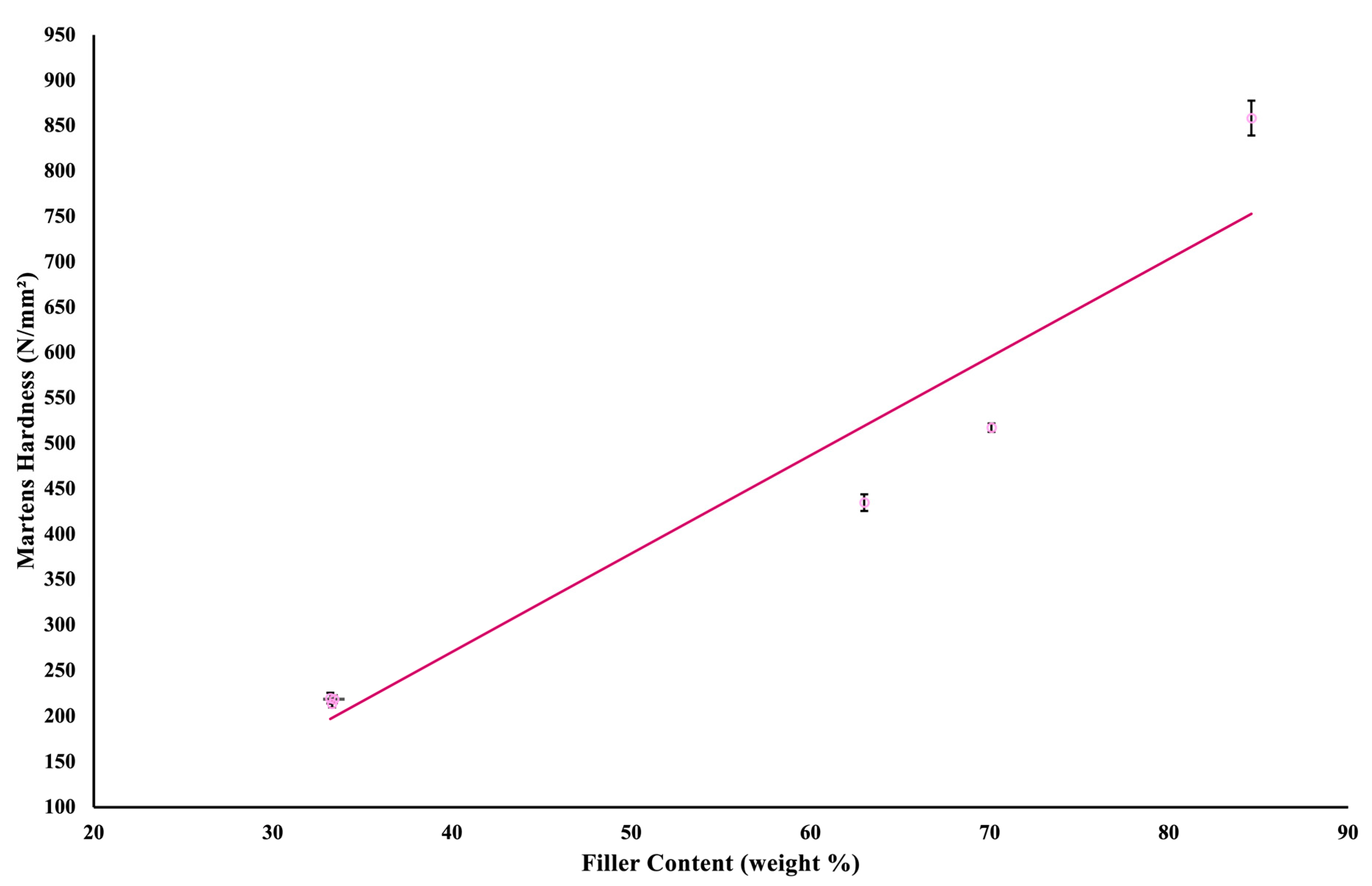

3.3. Martens Hardness and Indentation Modulus

3.4. Vickers Hardness

4. Discussion

4.1. Filler Content

4.2. Flexural Strength and Modulus

4.3. Hardness

4.3.1. Martens Hardness and Indentation Modulus

4.3.2. Vickers Hardness

4.4. Flexural Modulus vs. Indentation Modulus

4.5. Methodological Considerations and Future Research

4.6. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

- Filler content was strongly associated with flexural strength and Martens hardness of the tested materials.

- Milled composites exhibited superior mechanical properties due to their higher filler content compared with 3D-printed materials.

- All tested materials exceeded the ISO minimum requirements for flexural strength (100 MPa); however, the milled resin composites showed markedly higher stiffness and hardness.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beuer, F.; Schweiger, J.; Edelhoff, D. Digital dentistry: An overview of recent developments for CAD/CAM generated restorations. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Hotta, Y. CAD/CAM systems available for the fabrication of crown and bridge restorations. Aust. Dent. J. 2011, 56, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunchel, S.; Blay, A.; Kolerman, R.; Mijiritsky, E.; Shibli, J.A. 3D printing/additive manufacturing single titanium dental implants: A prospective multicenter study with 3 years of follow-up. Int. J. Dent. 2016, 2016, 8590971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstiel, S.F.; Land, M.F. Part II: Clinical procedures. In Contemporary Fixed Prosthodontics, 5th ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 209–235. [Google Scholar]

- Sailer, I.; Makarov, N.A.; Thoma, D.S.; Zwahlen, M.; Pjetursson, B.E. All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part I Single Crowns Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Hotta, Y.; Kunii, J.; Kuriyama, S.; Tamaki, Y. A review of dental CAD/CAM: Current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dent. Mater. J. 2009, 28, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawood, A.; Marti, B.M.; Sauret-Jackson, V.; Darwood, A. 3D printing in dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 2015, 219, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.; Osman, R.; Wismeijer, D. Effects of build direction on the mechanical properties of 3D-printed complete coverage interim dental restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanam, P.N.; Al-Maadeed, M.; Khanam, P.N. Silk as a reinforcement in polymer matrix composites. In Advances in Silk Science and Technology, 1st ed.; Basu, A., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi, R.L.; Powers, J.M. Restorative materials—Composites and polymers. In Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials, 13th ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 135–170. [Google Scholar]

- Shahdad, S.A.; McCabe, J.F.; Bull, S.; Rusby, S.; Wassell, R.W. Hardness measured with traditional vickers and martens hardness methods. Dent. Mater. 2007, 23, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Özcan, M.; Hallmann, L.; Ender, A.; Mehl, A.; Hämmerlet, C.H. The effect of zirconia sintering temperature on flexural strength, grain size, and contrast ratio. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhaffer, S.; Haider, J.; Satterthwaite, J.; Silikas, N. Effects of print orientation and artificial aging on the flexural strength and flexural modulus of 3D printed restorative resin materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 133, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhaffer, S.; Althagafi, R.; Haider, J.; Satterthwaite, J.; Silikas, N. Effects of printing orientation and artificial ageing on martens hardness and indentation modulus of 3D printed restorative resin materials. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 1172:1996; Textile-Glass-Reinforced Plastics—Prepregs, Moulding Compounds and laminates—Determination of the Textile-Glass and Mineral-Filler Content—Calcination Methods. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996.

- BS EN ISO 4049:2019; Dentistry—Polymer-Based Restorative Materials. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- BS EN ISO 14577-4:2016; Metallic Materials—Instrumented Indentation Test for Hardness and Materials Parameters—Part 4: Test Method for Metallic and Non-Metallic Coatings. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 6507-1:2023; Metallic Materials—Vickers Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Alamoush, R.A.; Silikas, N.; Salim, N.A.; Al-Nasrawi, S.; Satterthwaite, J.D. Effect of the composition of CAD/CAM composite blocks on mechanical properties. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4893143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolea, H.; Degeratu, S.; Deva, V.; Coles, E.; Draghici, E. Contributions on the study of the compressive strength of the light-cured composite resins. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2009, 35, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyasaka, T.; Okamura, H. Dimensional change measurements of conventional and flowable composite resins using a laser displacement sensor. Dent. Mater. J. 2009, 28, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebieluch, W.; Kowalewski, P.; Grygier, D.; Rutkowska-Gorczyca, M.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Jurczyszyn, K. Printable and machinable dental restorative composites for CAD/CAM application—Comparison of mechanical properties, fractographic, texture and fractal dimension analysis. Materials 2021, 14, 4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leprince, J.; Palin, W.M.; Mullier, T.; Devaux, J.; Vreven, J.; Leloup, G. Investigating filler morphology and mechanical properties of new low-shrinkage resin composite types. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, L.D.; Palin, W.M.; Leloup, G.; Leprince, J.G. Filler characteristics of modern dental resin composites and their influence on physico-mechanical properties. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfakhri, F.; Alkahtani, R.; Li, C.; Khaliq, J. Influence of filler characteristics on the performance of dental composites: A comprehensive review. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 27280–27294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebieluch, W.; Mikulewicz, M.; Kaczmarek, U. Resin composite materials for chairside CAD/CAM restorations: A comparison of selected mechanical properties. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 8828954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niem, T.; Youssef, N.; Wöstmann, B. Influence of accelerated ageing on the physical properties of CAD/CAM restorative materials. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 2415–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabo, A.; Xia, W.; Liaqat, S.; Khan, M.A.; Knowles, J.C.; Ashley, P.; Young, A.M. Conversion, shrinkage, water sorption, flexural strength and modulus of re-mineralizing dental composites. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Sayed, M.E.; Shetty, M.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Al Wadei, M.H.D.; Gupta, S.G.; Othman, A.A.A.; Alshehri, A.H.; Alqarni, H.; Mobarki, A.H.; et al. Physical and mechanical properties of 3D-printed provisional crowns and fixed dental prosthesis resins compared to CAD/CAM milled and conventional provisional resins: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Polymers 2022, 14, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşın, S.; Ismatullaev, A. Comparative evaluation of the effect of thermocycling on the mechanical properties of conventionally polymerized, CAD-CAM milled, and 3D-printed interim materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 173.e171–173.e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temizci, T.; Bozoğulları, H.N. Effect of thermocycling on the mechanical properties of permanent composite-based CAD-CAM restorative materials produced by additive and subtractive manufacturing techniques. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, N.A.-H.; Feilzer, A.J.; Kleverlaan, C.J.; Abou-Ayash, S.; Özcan, M. Effect of hydrothermal aging on the microhardness of high-and low-viscosity conventional and additively manufactured polymers. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 822.e821–822.e829. [Google Scholar]

- Ilie, N.; Hilton, T.J.; Heintze, S.D.; Hickel, R.; Watts, D.C.; Silikas, N.; Stansbury, J.W.; Cadenaro, M.; Ferracane, J.L. Academy of dental materials guidance—Resin composites: Part I—Mechanical properties. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues Junior, S.A.; Zanchi, C.H.; Carvalho, R.V.d.; Demarco, F.F. Flexural strength and modulus of elasticity of different types of resin-based composites. Braz. Oral Res. 2007, 21, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavi, A.; Origlia, C.; Germak, A.; Prato, A.; Genta, G. Indentation modulus, indentation work and creep of metals and alloys at the macro-scale level: Experimental insights into the use of a primary vickers hardness standard machine. Materials 2021, 14, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yan, C.; Shi, Y.; Kong, L.B.; Qi, H.J.; Zhou, K. 3D-printed anisotropic polymer materials for functional applications. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Özcan, M. Additive manufacturing technologies used for processing polymers: Current status and potential application in prosthetic dentistry. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Name | Composition | Inorganic Fillers | Manufacturer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-printed | Permanent Crown Resin (PCR) | Esterification products of 4,4’-isopropylidiphenol, ethoxylated and 2-methylprop-2enoic acid, ethoxylated bisphenol A dimethacrylate (Bis-EMA, methacrylate polymer) methyl benzoylformate, diphenyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide (TPO, photoinitiator) | Silanized dental glass | Formlabs (Somerville, MA, USA) |

| VarseoSmile Crown plus (VCP) | Esterification product of 4.4‘-isopropylidiphenol, ethoxylated and 2-methyl- prop-2enoic acid. methyl benzoylformate, diphenyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide (TPO, photoinitiator) | Silanized dental glass | BEGO GmbH & Co. KG (Bremen, Germany) | |

| Crowntec (CT) | BisEMA, trimethylbenzoyldiphenylphosphine oxide (TPO, photoinitiator) | Pyrogenic silica Silanized dental glass | Saremco Dental AG (Rebstein, Switzerland) | |

| Milled | Brilliant Crios (BC) | Cross-linked methacrylates (Bis-GMA, Bis-EMA, TEGDMA) | Barium glass and amorphous silica | COLTENE (Altstatten, Switzerland) |

| Shofu Block HC (HC) | UDMA, TEGDMA | Silica powder, microfumed silica, and zirconium silicate | Shofu (Kyoto, Japan) | |

| Grandio Blocs—HT (Gr) | 14% UDMA, DMA | Nanohybrid fillers | VOCO GmbH (Cuxhaven, Germany) |

| Material Name | 3D Printer/Techniques | Cleaning Solution in Form Wash | Post-Curing | Post-Curing Device |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Form 3B (Formlabs)/(SLA) | 99% isopropyl alcohol | 2 × 20 min at 60 °C | Form Cure (Formlabs, Somerville, MA, USA) |

| VCP | Asiga MAX/(DLP) | 96% ethanol | 2 × 1500 flashes | Otoflash (BEGO GmbH & Co. KG, Bremen, Germany) |

| CT | Asiga MAX/(DLP) | 99% isopropyl alcohol | 2 × 2000 flashes | Otoflash (BEGO GmbH & Co. KG, Bremen, Germany) |

| Material Name | Manufacturer Filler Weight % | Measured Filler Weight % Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| PCR | 30–50 | 33.4 (0.6) |

| VCP | 30–50 | 33.3 (0.05) |

| CT | 30–50 | 33.2 (0.09) |

| BC | 70 | 70.1 (0.05) [19] |

| HC | 61 | 63.0 (0.02) [19] |

| Gr | 86 | 84.6 (0.01) [19] |

| Parameter | Source of Variation | Sum of Squares | df | F | p Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS | Material | 240,013.479 | 5 | 396.567 | <0.001 | 0.948 |

| Storage | 3407.247 | 1 | 28.148 | <0.001 | 0.207 | |

| Storage | 3735.946 | 5 | 6.173 | <0.001 | 0.222 | |

| FM | Material | 1,158,706,936.666 | 5 | 1767.244 | <0.001 | 0.988 |

| Storage | 2,964,163.333 | 1 | 22.605 | <0.001 | 0.173 | |

| Storage | 1,569,736.667 | 5 | 2.394 | =0.042 | 0.100 |

| Material Name | Martens Hardness (N/mm2) Mean (SD) | Indentation Modulus (kN/mm2) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| PCR | 218.6 d (4.2) | 6.0 d (0.1) |

| VCP | 213.6 d (4) | 5.7 d (0.1) |

| CT | 219.7 d (5.9) | 5.8 d (0.2) |

| BC | 517.3 b (4.6) | 14.5 b (0.3) |

| HC | 434.7 c (9.2) | 10.9 c (0.6) |

| Gr | 858.4 a (19.2) | 22.7 a (0.9) |

| Material Name | Measured by Zwick (HV) Mean (SD) | Measured by Vickers (HV) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| PCR | 29.8 d (0.6) | 29.5 c (0.8) |

| VCP | 29.3 d (0.7) | 31.2 c (0.6) |

| CT | 30.3 d (0.8) | 30.3 c (1) |

| BC | 70.2 b (0.7) | 68.6 b (0.9) |

| HC | 62.1 c (1.7) | 67.2 b (3) |

| Gr | 119.5 a (2.3) | 119.1 a (3.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tayeb, H.K.; Silikas, N.; Alhaddad, A.J.; Satterthwaite, J. Flexural Strength and Hardness Analysis of 3D-Printed vs. Milled Resin Composites Indicated for Definitive Crowns. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120468

Tayeb HK, Silikas N, Alhaddad AJ, Satterthwaite J. Flexural Strength and Hardness Analysis of 3D-Printed vs. Milled Resin Composites Indicated for Definitive Crowns. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(12):468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120468

Chicago/Turabian StyleTayeb, Hunaida Khaled, Nick Silikas, Abdulrahman Jafar Alhaddad, and Julian Satterthwaite. 2025. "Flexural Strength and Hardness Analysis of 3D-Printed vs. Milled Resin Composites Indicated for Definitive Crowns" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 12: 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120468

APA StyleTayeb, H. K., Silikas, N., Alhaddad, A. J., & Satterthwaite, J. (2025). Flexural Strength and Hardness Analysis of 3D-Printed vs. Milled Resin Composites Indicated for Definitive Crowns. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(12), 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120468