The Psychological Effects of AI Learning Assistants in Immersive Virtual Reality Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Confluence of AI and VR in Education

1.2. Research Objectives

- •

- Identify and categorize the positive psychological effects, including cognitive, emotional, and motivational benefits.

- •

- Identify and categorize the negative psychological effects and challenges such as cognitive overload, anxiety, and over-reliance.

- •

- Explore the nuanced concept of student trust in an AI tutor and its relationship with learning outcomes.

- •

- Discuss the ethical and practical challenges of implementation, including the digital divide.

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. The Psychological Impact of Virtual Reality in Education

2.2. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Student Psychological Development

2.3. The Psychological Impact of VFTs and the Gap in AI-Enhanced Immersion

3. Analysis of Key Psychological Effects of the Combined AI-VR System

3.1. Cognitive and Attentional Effects

3.2. Emotional and Motivational Responses

3.3. Social and Behavioral Impacts

4. Design and Implementation of the Pilot Study

4.1. Initial Development Concept (ThirdEye X2)

4.2. Transition to Meta Quest 2 and Final Implementation

4.3. Implementation Features

- •

- Exploration and navigation: Users could move freely through an immersive 3D version of Athens using joystick navigation, similar to Google Maps, rather than being restricted to a single position.

- •

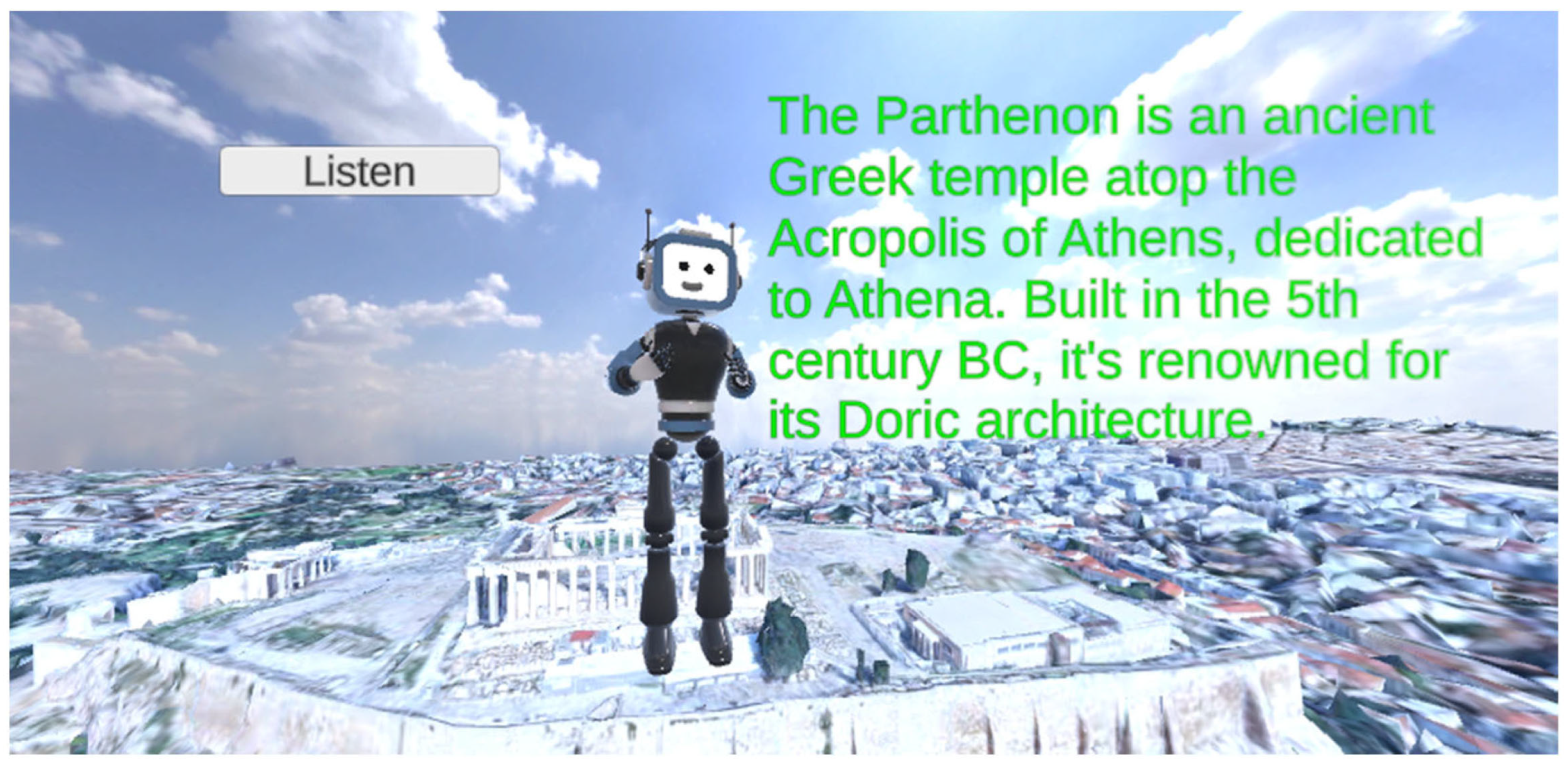

- Color-coded feedback: Pre-programmed responses appeared in green text, while dynamically generated ChatGPT responses were shown in red text, giving users clear transparency over the source of information (Figure 2).

4.4. Core Technologies Involved

- •

- Meta Quest 2: The VR headset chosen as the primary platform due to its strong developer ecosystem and compatibility with Unity.

- •

- Unity: The game engine used to build and integrate the application environment.

- •

- OpenAI API: Enabled communication with the gpt-3.5-turbo model to generate dynamic, AI-driven responses.

- •

- Oculus Voice SDK: Provided Speech-to-Text (STT) and Text-to-Speech (TTS) functionality for natural voice interaction.

- •

- Meta XR All-in-One SDK: Offered preconfigured “Building Blocks” that streamlined setup of core VR functions, such as camera configuration, hand tracking, and controller input.

- •

- Wit.ai: Served as the natural language processing layer, trained to identify user intents and extract relevant entities from voice commands.

- •

- Google Maps Platform with Cesium for Unity: Delivered high-fidelity 3D mapping, allowing accurate visualization of Athens landmarks within the VR environment.

4.5. Advanced Features Involved

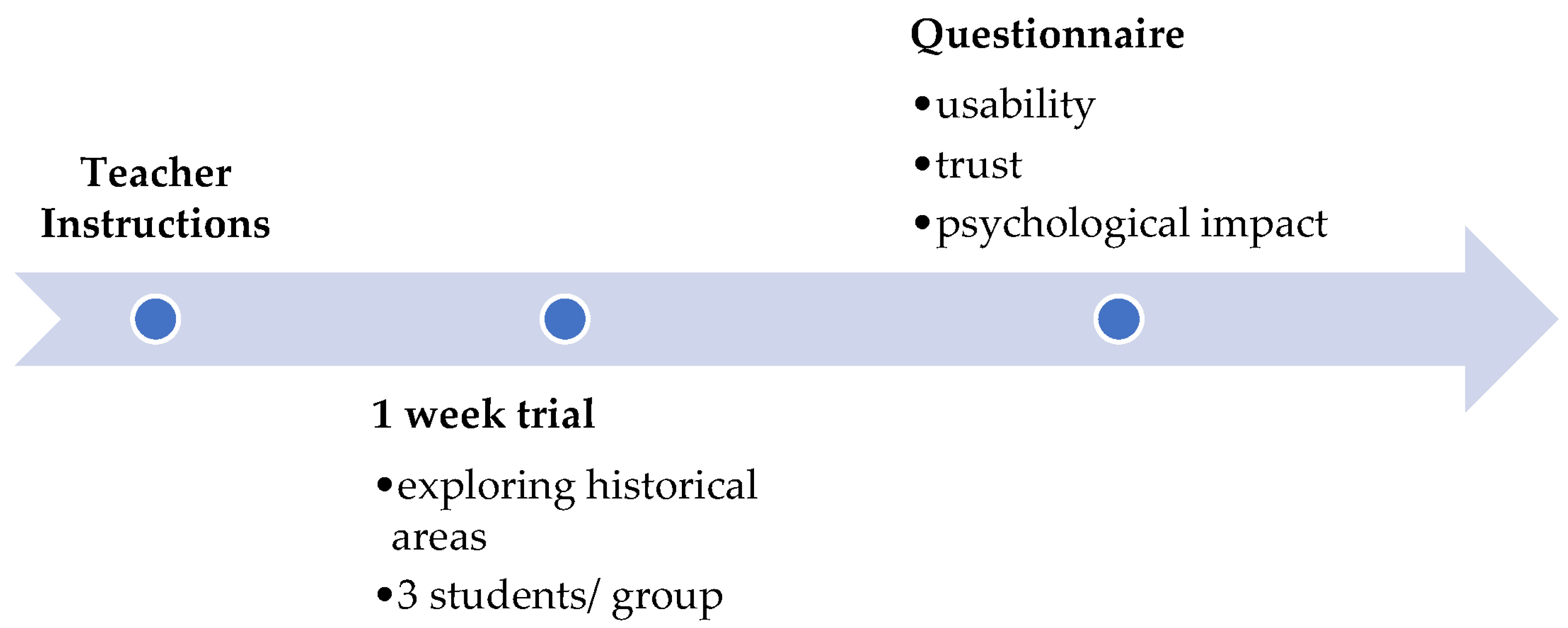

5. Case Study: A Proposed Study on AI-VR Learning for High School Students

5.1. Methodology Rationale and Demographics

Data Analysis and Instrumentation

5.2. Expected Key Psychological Findings

5.2.1. Role of the Educator and Social Influence

5.2.2. User Perception and Trust in AI

5.2.3. Functionality and Cognitive Load

5.2.4. Broader Psychological Impacts

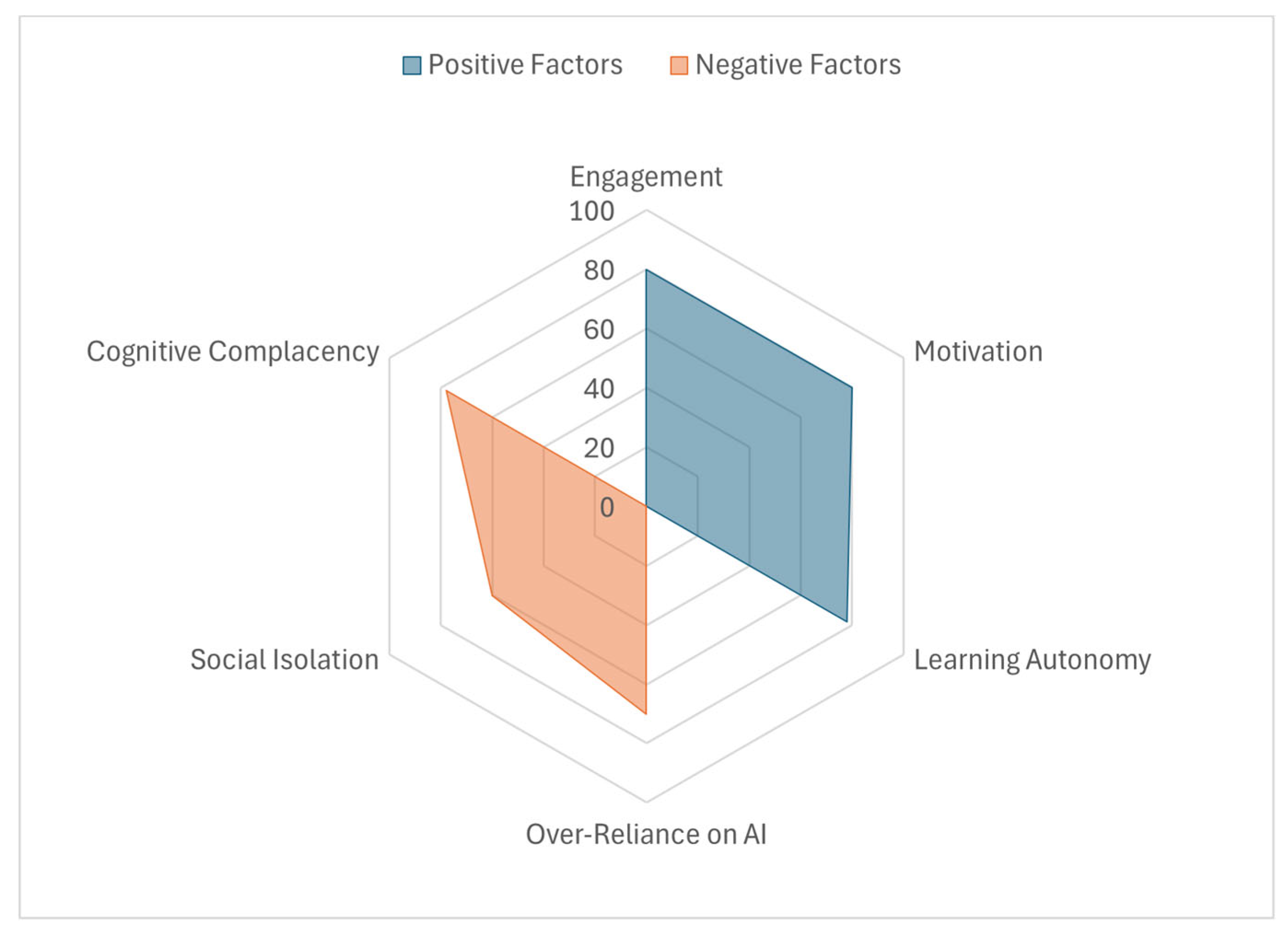

- Positive Impacts: The immersive nature of the VR environment combined with the AI assistant’s personalized feedback is expected to increase student engagement and motivation [46]. The ability to learn at their own pace and explore virtual concepts hands-on can foster a sense of self-efficacy and learning autonomy [30,33].

- Negative Impacts: If the system design does not adequately mitigate potential risks, it could lead to negative outcomes. A heavy reliance on the AI plugin for answers could diminish critical thinking and problem-solving skills [30]. Furthermore, a lack of collaborative features could increase the risk of social isolation, as it may reduce face-to-face interactions that are crucial for developing interpersonal skills in a classroom setting [41].

5.3. Case Study Findings

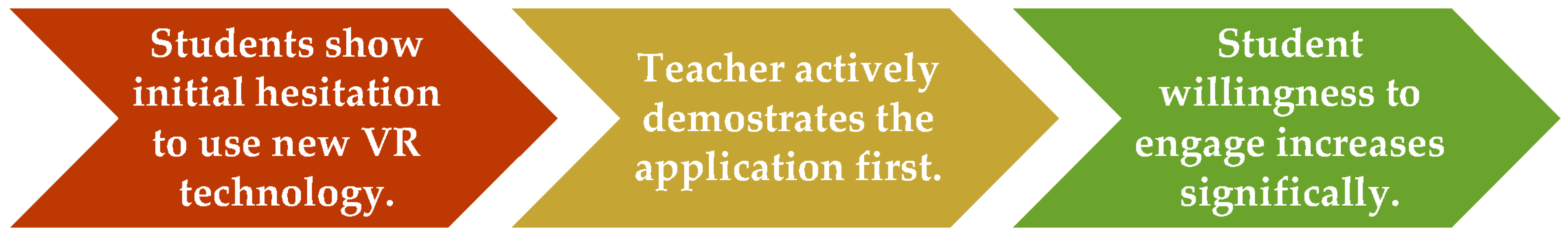

- F1: Role of the Educator and Social Influence

- Students were hesitant to use the VR headset until the teacher demonstrated or encouraged its use, reflecting the teacher’s role as a key social mediator in technology adoption.

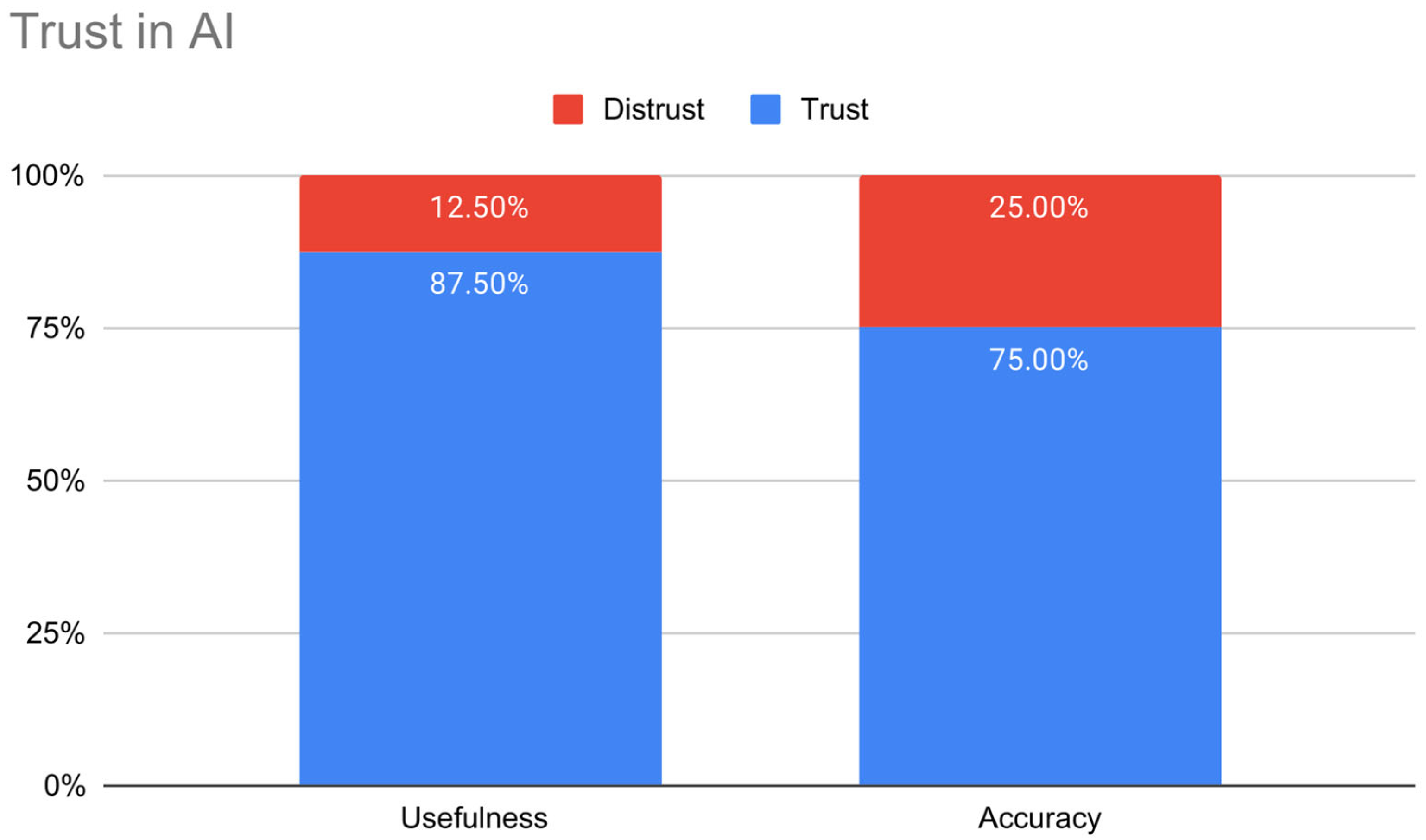

- F2: User Perception and Trust in AI

- Students perceived the AI assistant as a useful and convenient tool for quick access to information but will show lower trust in its accuracy compared to human teachers, especially for tasks requiring nuanced judgment.

- F3: Functionality and Cognitive Load

- Students with lower English proficiency experienced higher cognitive load and frustration when using voice commands, underscoring the need for multilingual support or alternative input methods to ensure inclusivity.

6. Ethical and Practical Implications

6.1. The Ethical Framework of AI-VR in Education

6.2. Overcoming Implementation Obstacles

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

7.1. Summary of Findings

7.2. Study Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

7.3. Recommendations for Design and Implementation

- •

- System Design: Developers should move beyond creating “AI-as-a-tutor” systems that simply provide answers. Instead, the focus should be on building “AI-in-the-loop” systems that require active student participation and human oversight. The system should encourage students to engage critically with the information, for example, by prompting them to justify their reasoning or cross-reference sources. This design approach can mitigate the psychological risk of over reliance and promote the development of critical thinking skills.

- •

- Educational Integration: Educators must be trained to act as “facilitators of technology” rather than passive observers. As evidenced by the pilot study, their role is crucial in overcoming the initial psychological barrier to adoption. Educators should guide students on how to use the AI-VR system critically, to value human interaction and collaborative learning, and to understand the limitations of this technology.

- •

- Ethical Safeguards: The psychological well-being of students is paramount. Robust ethical frameworks must be put in place to ensure data privacy, transparency in data usage, and mechanisms to address algorithmic bias. This will foster a sense of trust and security, which is a key psychological prerequisite for effective technology adoption.

- •

- Accessibility: To address the digital divide and its psychological consequences, institutions and policymakers must prioritize providing equitable access to hardware and training. Making these technologies widely available, rather than a luxury, will ensure that all students have the opportunity to benefit from an enhanced learning experience.

- •

- Multilingual Support: The pilot study revealed a critical need for language support beyond English. While full voice command functionality in every language may not be feasible, systems should provide multilingual subtitles for AI-generated responses and allow for voice command systems in native language. This would reduce cognitive load and frustration for non-native English speakers, making the system more inclusive and psychologically accessible.

7.4. Future Research

- ●

- Issue No 1: Longitudinal Studies

- ●

- The existing literature lacks long-term studies on the psychological outcomes of AI-VR interaction. Future research should investigate the long-term effects on student critical thinking, social skill development, and potential over-reliance on technology [31].

- ●

- Issue No 2: Embodiment and Trust

- ●

- ●

- Issue No 3: Cross-Cultural and Linguistic Nuances

- ●

- The pilot study’s finding that students with a low proficiency in English struggled with voice commands highlights the need for research into the psychological effects of such systems across diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. This would inform the development of more inclusive and accessible educational tools that account for global user needs [16].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| VFTs | Virtual Field Trips |

| VPS | Visual Positioning System |

References

- Lazou, C.; Tsinakos, A.; Kazanidis, I. Enhancing Multiliteracy Through Virtual Reality: An Inclusive Approach to Critical Immersive-Triggered Literacy. In Immersive Learning Research Network; Krüger, J.M., Schmidt, M., Mikropoulos, A., Koutromanos, G., Pedrosa, D., Beck, D., Mystakidis, S., Smith-Nunes, G., Peña-Rios, A., Richter, J., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 2598, pp. 198–215. ISBN 978-3-031-98079-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lazou, C.; Tsinakos, A. Critical Immersive-Triggered Literacy as a Key Component for Inclusive Digital Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazou, C.; Tsinakos, A.; Kazanidis, I. Critical Digital Skills Enhancement in Virtual Reality Environments. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), Orem, UT, USA, 10–13 July 2023; IEEE: Orem, UT, USA, 2023; pp. 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Long, L.; Tsinakos, A. The Use of Virtual Reality to Develop Presentation Skills in Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Select Commercial Technologies. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 2025, 36, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Digital Education Outlook 2021: Pushing the Frontiers with Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain and Robots; OECD Digital Education Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 978-92-64-64199-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pietro, L.; Sleeman, D.; Tsinakos, A. S-SALT: A Problem-Solver, Knowledge Acquisition Tool and Associate Knowledge Base Refinement Mechanism. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 1996, 10, 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Tsinakos, A.; Margaritis, K. Student Models: The Transit to Distance Education. Eur. J. Open Distance Learn. EURODL 2000, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Neelakantan, S. Successful AI Examples in Higher Education That Can Inspire Our Future. Available online: https://edtechmagazine.com/higher/article/2020/01/successful-ai-examples-higher-education-can-inspire-our-future (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Holmes, W.; Bialik, M.; Fadel, C. Artificial Intelligence in Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning; The Center for Curriculum Redesign: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-7942-9370-0. [Google Scholar]

- King, I. Maximizing Student Learning: The Transformative Potential of VR in Education. AI Tutor Platf. VR Labs 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lampropoulos, G. Combining Artificial Intelligence with Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Education: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, I. Immersive Virtual Field Trips and Elementary Students’ Perceptions. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.-H.; Tsai, C.-C. A Case Study of Immersive Virtual Field Trips in an Elementary Classroom: Students’ Learning Experience and Teacher-Student Interaction Behaviors. Comput. Educ. 2019, 140, 103600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, M.; Rodríguez, F.; Merchán, M.J.; Merchán, P.; Pérez, E. Comparative Analysis between Virtual Visits and Pedagogical Outings to Heritage Sites: An Application in the Teaching of History. Heritage 2024, 7, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rodrigo, A.; Morales, E.; Lakoud, M.; Riendeau, J.; Lemay, M.; Savaria, A.; Mathieu, S.; Feillou, I.; Routhier, F. Experiencing Accessibility of Historical Heritage Places with Individuals Living with Visible and Invisible Disabilities. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2024, 5, 1379139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teazi, N. Educational Use of VR Headsets. Bachelor’s Thesis, Democritus University of Thrace: Kavala, Greece, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Lee, S. Ethics, Equity, and the Augmented Classroom: A Comprehensive Overview of AI in Secondary Education; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, D. Virtual Reality in Adolescent Mental Health Management under the New Media Communication Environment. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Bearman, M.; Chung, J.; Fawns, T.; Buckingham Shum, S.; Matthews, K.E.; de Mello Heredia, J. Comparing Generative AI and Teacher Feedback: Student Perceptions of Usefulness and Trustworthiness. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2025, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L. The Effects of Virtual Reality Learning Environment on Student Cognitive and Linguistic Development. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2016, 25, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, J.; Li, B. The dual-edged sword: Cognitive load and performance in personalized VR learning environments. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Virtual Reality and Education (ICVRE), Bournemouth, UK, 24 July–26 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ryder, L.H. Effects of using mobile-based virtual reality on Chinese L2 students’ oral proficiency. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 34, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Xu, J.; Yu, J.; Chu, X. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality Therapy in the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Adolescents and Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1553290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temirova, R. Psychological and Cognitive Impacts of Virtual Reality in Education. J. Sci.-Innov. Res. Uzb. 2024, 2, 665–672. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, T. Teaching in a Digital Age: Guidelines for Designing, Teaching and Learning, 2nd ed.; Tony Bates Associates Ltd.: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/teachinginadigitalagev2/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ünal, E.; Çakır, H. Use of dynamic web technologies in collaborative problem-solving method at community colleges. In Student-Centered Virtual Learning Environments in Higher Education; Yilmaz, S., Ed.; IGI Global: Mumbai, India, 2019; pp. 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S.; Luxton-Reilly, A.; Wuensche, B.; Plimmer, B. A systematic review of virtual reality in education. Themes Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 10, 85–119. [Google Scholar]

- Long, L. AI Human Rights Impact Assessment for Educators (AIHRIAE); University of Waterloo: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://uwaterloo.ca/conflict-management-human-rights/ai-human-rights-impact-assessment-tools (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Wilczyńska, D.; Walczak-Kozłowska, T.; Alarcón, D.; Arenilla, M.J.; Jaenes, J.C.; Hejła, M.; Lipowski, M.; Nestorowicz, J.; Olszewski, H. The Role of Immersive Experience in Anxiety Reduction: Evidence from Virtual Reality Sessions. Brain Sci. 2024, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Bej, T. Psychological Impacts of AI Use on School Students: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Empirical Literature. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2024, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzar, M.; Mahmudulhassan; Muthoifin. University Students’ Trust in AI: Examining Reliance and Strategies for Critical Engagement. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. IJIM 2025, 19, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. A New Era of Cultural Heritage Field Trips: Enhancing Historic Preservation Interpretation through Virtual Reality, with a Case Study on Low Library Rotunda; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, G.B.; Klingenberg, S.; Mayer, R.E.; Makransky, G. The Virtual Field Trip: Investigating How to Optimize Immersive Virtual Learning in Climate Change Education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 2099–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofianto, O.; Erniwati, E.; Fitrisia, A.; Ningsih, T.Z.; Mulyani, F.F. Development of Online Local History Learning Media Based on Virtual Field Trips to Enhance the Use of Primary Source Evidence. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 12, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, Ü. We’ve All Traveled, We’ve All Learnt: Virtual Field Trips in Early Childhood Education. Anadolu Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Derg. 2023, 7, 883–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Dai, T.; Sedini, C.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Li, J.; Zhu, K.; Zhai, B.; Li, M.; et al. Virtual Reality in Heritage Education for Enhanced Learning Experience: A Mini-Review and Design Considerations. Front. Virtual Real. 2025, 6, 1560594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmote Chronos. Your Athens Guide. On line AR App. Available online: https://yourathensguide.gr/place/cosmote-chronos/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- ARcheos—Chat with the Greats of the Past! Available online: https://geosquadai.github.io/archeos/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Rong, Q.; Lian, Q.; Tang, T. Research on the Influence of AI and VR Technology for Students’ Concentration and Creativity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 767689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learns, W.; Future of AI and VR in Education: Scary Realities; Impacts. Medium 2024, Wiki Learns. Available online: https://medium.com/@wikilearns/future-of-ai-and-vr-in-education-scary-realities-impacts-c2316238d192 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- How VR and AI Are Bridging Gaps in Higher Education. Available online: https://www.ixrlabs.com/blog/how-vr-and-ai-are-bridging-gaps-in-higher-education/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Sophocleous, A. Θεωρίες Κινήτρων και Ενεργοποίηση του Aδιάφορου Μαθητή. Available online: https://www.pi.ac.cy/pi/files/epimorfosi/ergo/23_24/kinitra.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Pownall, I. Student Identity and Group Teaching as Factors Shaping Intention to Attend a Class. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2012, 10, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Extensions and improvements. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Wang, Q. Immersed in trust: The development and fragility of user confidence in AI guides within high-fidelity VR. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 415–430. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, R.E.; McWhorter, R.R.; Stone, K.; Coyne, L. Adopting Virtual Reality for Education: Exploring Teachers’ Perspectives on Readiness, Opportunities, and Challenges. Int. J. Integr. Technol. Educ. 2023, 12, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsinakos, A.; Teazi, N.; Tsinakou, S. The Psychological Effects of AI Learning Assistants in Immersive Virtual Reality Environments. Information 2025, 16, 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121062

Tsinakos A, Teazi N, Tsinakou S. The Psychological Effects of AI Learning Assistants in Immersive Virtual Reality Environments. Information. 2025; 16(12):1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121062

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsinakos, Avgoustos, Nikoletta Teazi, and Styliani Tsinakou. 2025. "The Psychological Effects of AI Learning Assistants in Immersive Virtual Reality Environments" Information 16, no. 12: 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121062

APA StyleTsinakos, A., Teazi, N., & Tsinakou, S. (2025). The Psychological Effects of AI Learning Assistants in Immersive Virtual Reality Environments. Information, 16(12), 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121062