AVD-YOLO: Active Vision-Driven Multi-Scale Feature Extraction for Enhanced Road Anomaly Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

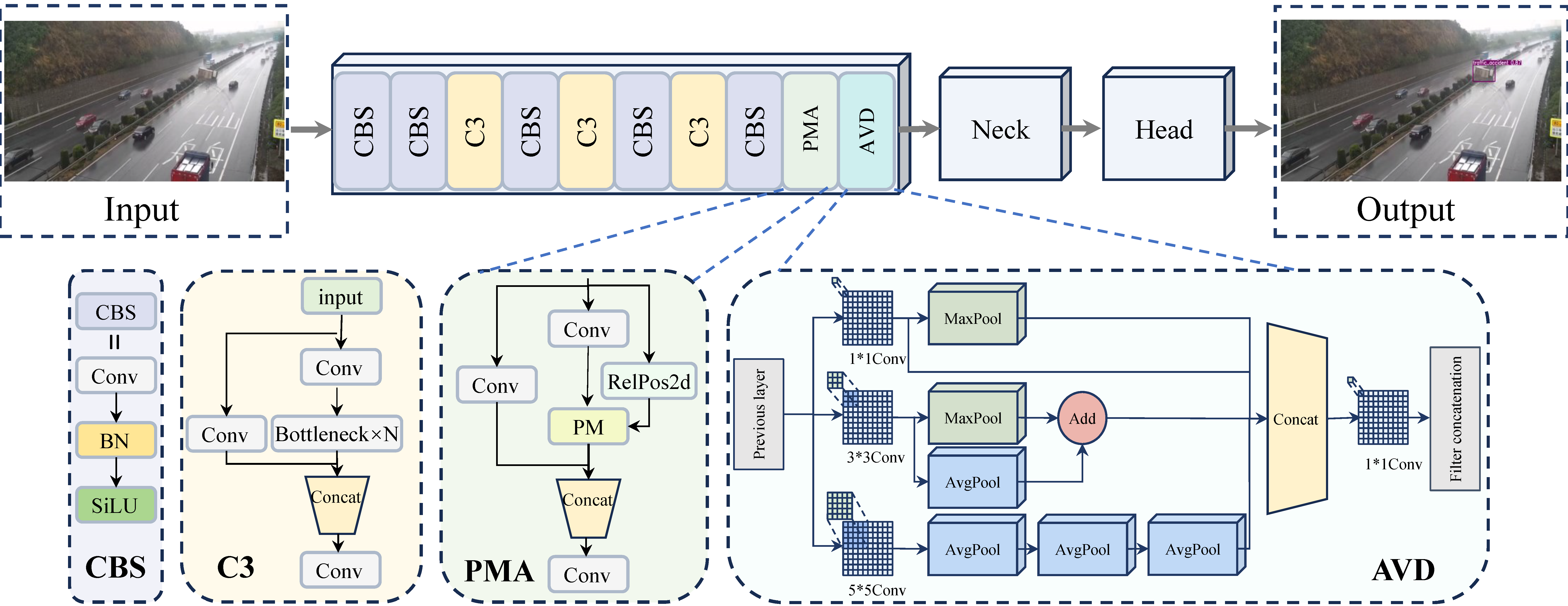

- Road environment complexities, including variations in light, weather, changing road conditions, and insignificant features of abnormal objects, often reduce target-background contrast, making accurate model perception and localization difficult. To overcome these limitations, a Position-Modulated Attention (PMA) module is proposed to efficiently capture long-range dependencies for precise localization, enhance scene adaptation, and improve the detection of weak-feature targets.

- (2)

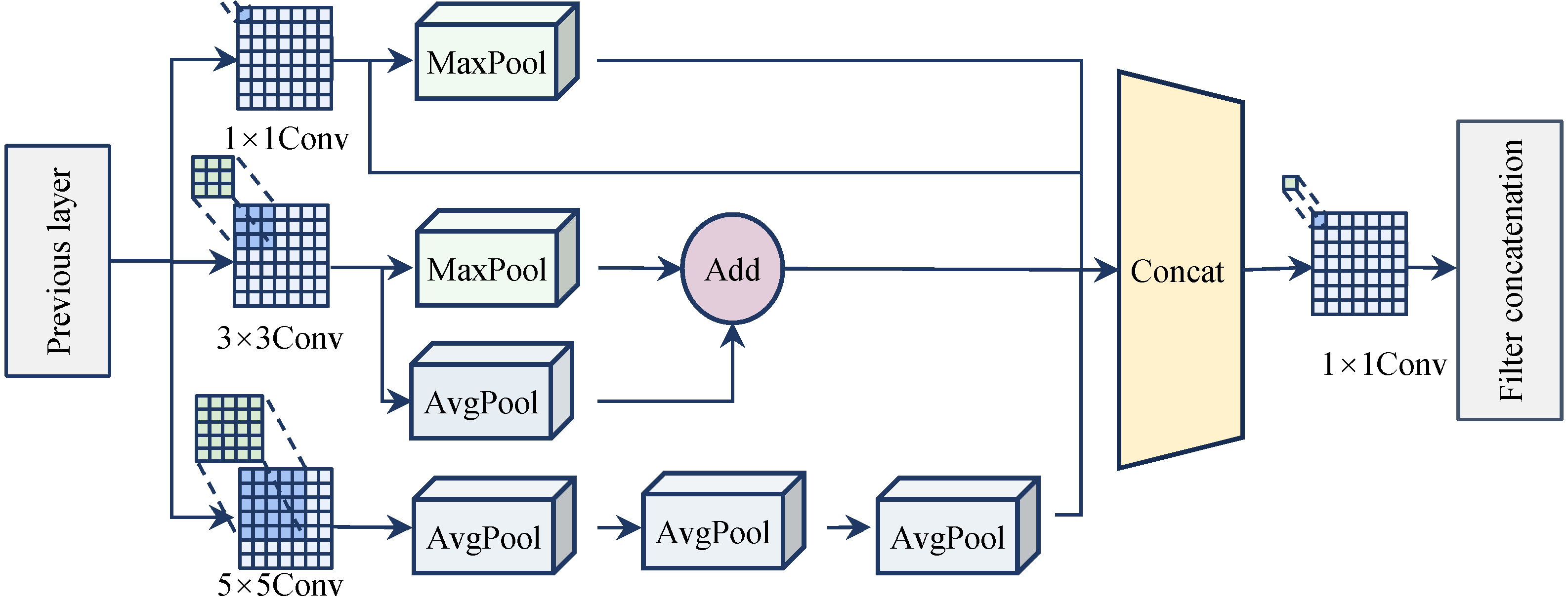

- In road anomaly detection, dynamic changes in the size of the target to be detected in the road scene due to the real-time view distance change caused by movement often lead to missed detections or reduced localization accuracy. An Active Vision Driven Multi-scale Feature Extraction (AVD) module is proposed, which performs multi-scale feature extraction from multiple receptive fields by actively adjusting the viewing distance while conceptually maintaining a fixed target position, thereby alleviating the limitations inherent in single-scale methods.

- (3)

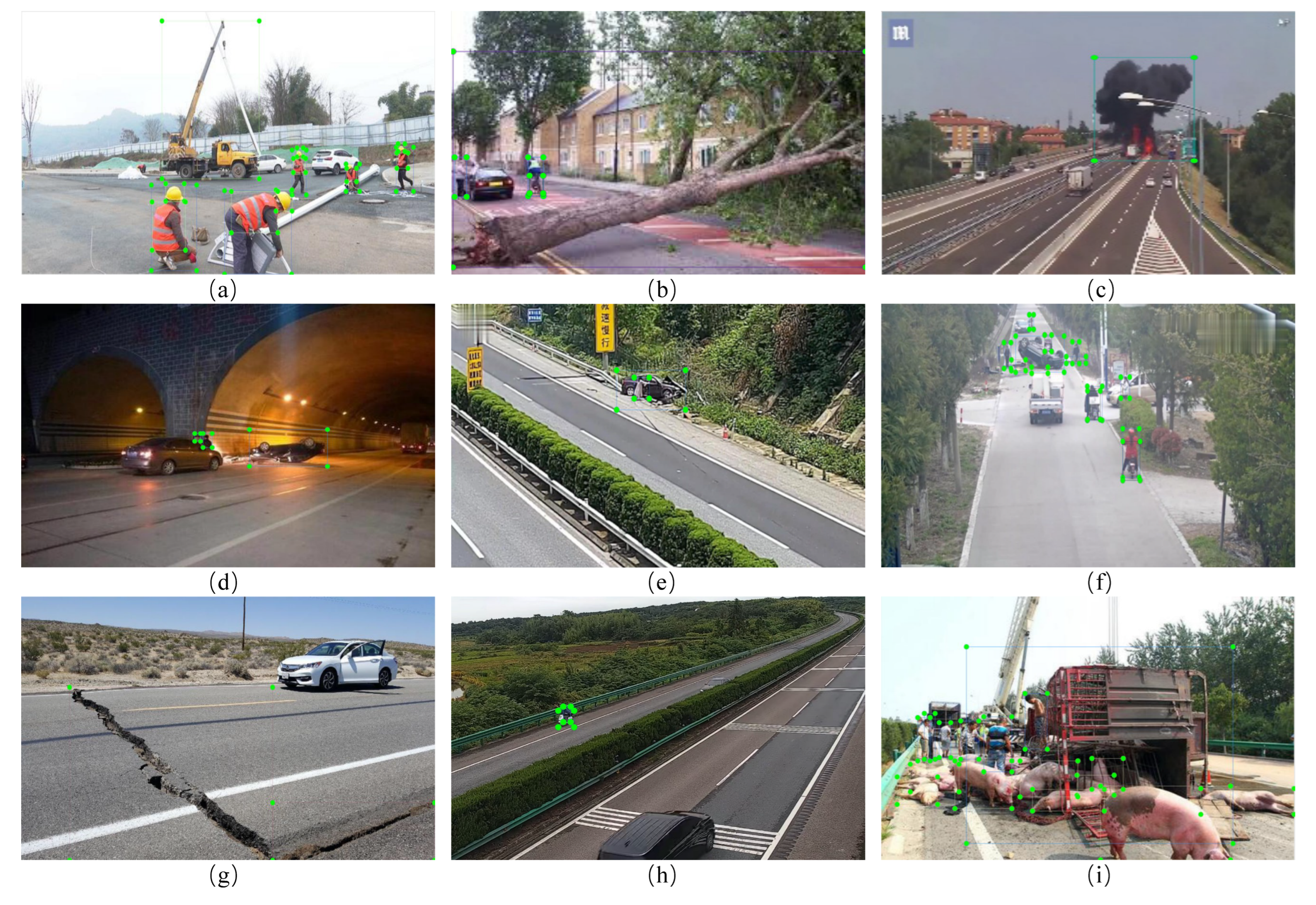

- Considering the difficulty of road data collection, the scarcity of public datasets, and the lack of clear anomaly classifications, MCRAD is constructed to define nine types of road anomalies and provide sufficient training data, thereby enabling robust detection within this defined scope.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. AVD-YOLO Backbone Network

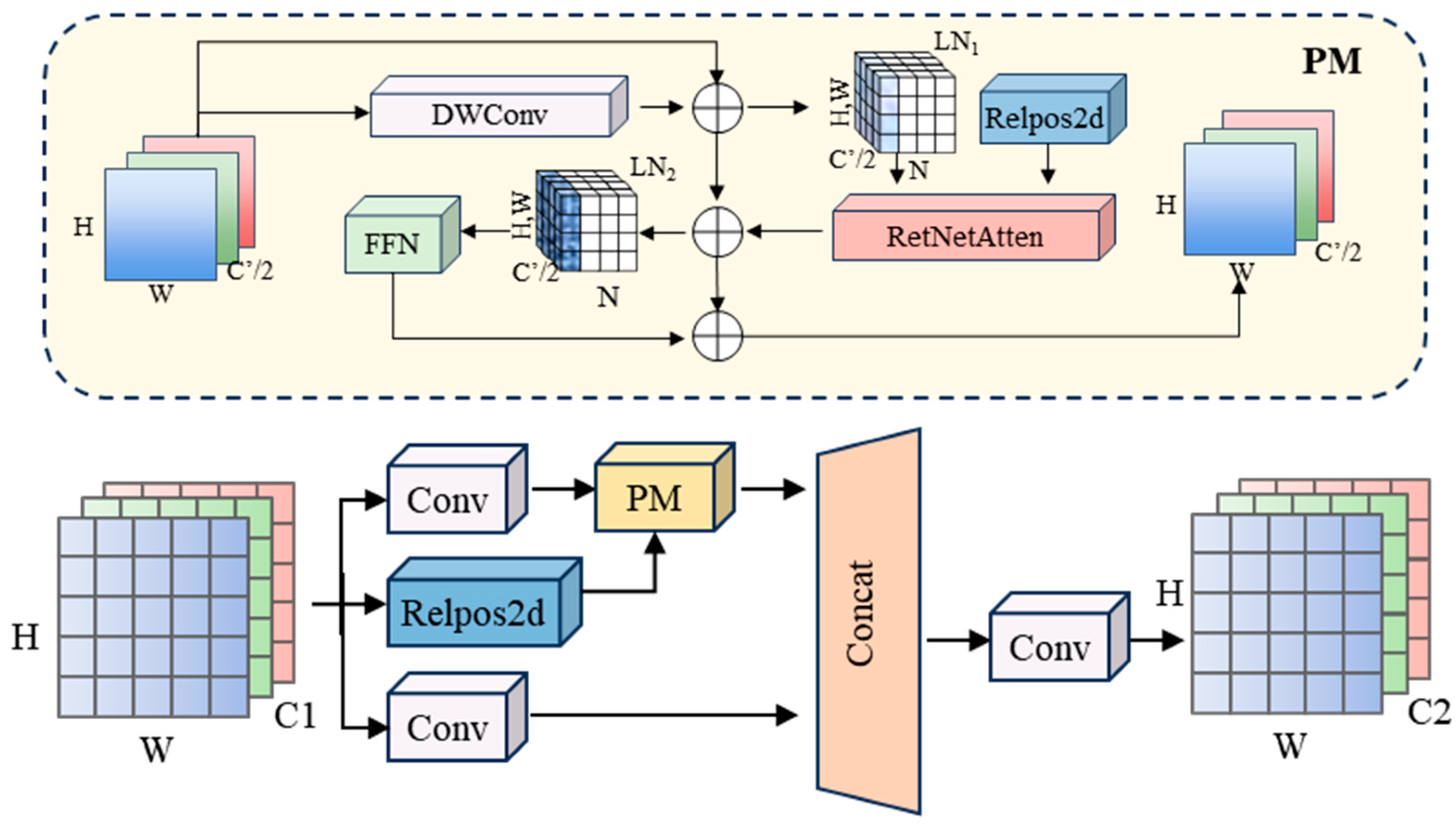

3.2. Position-Modulated Attention

3.3. Active Vision Driven Multi-Scale Feature Extraction

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Experimental Environment and Evaluating Indicator

4.3. Comparisons with Representative Methods

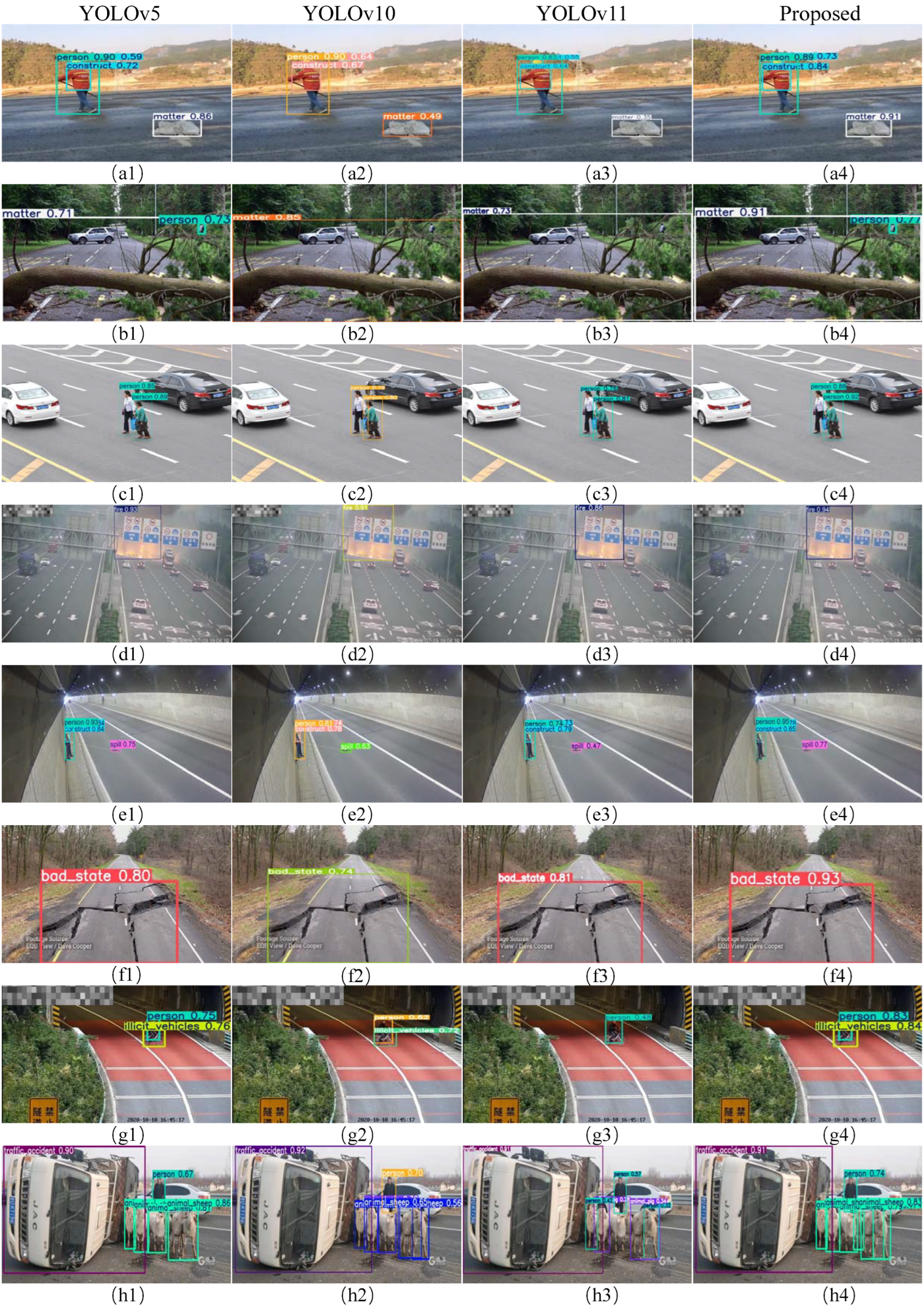

4.4. Comparison and Analysis of Visualization Results

4.5. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVD-YOLO | Active Vision Driven Multi-scale Feature Extraction for Enhanced Road Anomaly Detection |

| PMA | Position-Modulated Attention |

| AVD | Active Vision Driven Multi-scale Feature Extraction |

| DETR | DEtection TRansformer |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| MCRAD | Multi-Class Road Anomaly Dataset |

| RelPos2d | Two-Dimensional Relative Position Encoding |

| PM | Positional Modulator |

| LEPE | Local Enhancement Positional Encoding |

| DWConv | depthwise separable convolution |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

References

- Santhosh, K.K.; Dogra, D.P.; Roy, P.P. Anomaly detection in road traffic using visual surveillance: A survey. Acm. Com.-Puting Surv. (CSUR) 2020, 53, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Road Traffic Injuries. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Moraga, Á.; de Curtò, J.; de Zarzà, I.; Calafate, C.T. AI-Driven UAV and IoT Traffic Optimization: Large Language Models for Con-gestion and Emission Reduction in Smart Cities. Drones 2025, 9, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, W.; Xing, W. Dynamic Spatial-Temporal Perception Graph Convolutional Networks for Traffic Flow Forecasting. In Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision, Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV) Urumqi, China, 18–20 October 2024; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, J.; Gao, C.; Mu, M.; E, G.; Gu, C. Review of research on road traffic operation risk prevention and control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowthami, C.; Kavitha, S. Comprehensive approach to predictive analysis and anomaly detection for road crash fatalities. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 015022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Chang, X.; Xie, T.; Fujita, H.; Wu, J. Unsupervised anomaly detection based method of risk evaluation for road traffic accident. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Hsieh, S.Y.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Piran, J. A cooperative vehicle-road system for anomaly detection on vehicle tracks with augmented intelligence of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 35975–35988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, X.; He, S.; Song, H.; Zhao, Y.; Song, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, F.; et al. Review of pavement detection technology. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2017, 17, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. RAO-UNet: A residual attention and octave UNet for road crac k detection via balance loss. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 16, tdac026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Fan, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, L.; Fan, R. Computer vision for road imaging and pothole detection: A state-of-the-art review of systems and algorithms. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2022, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G. Ultralytics YOLOv5 (Version 7.0); GitHub: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5s (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO (Version 8.0.0). 2023. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/zh/models/yolov8/ (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2025, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO11 (Version 11.0.0); GitHub: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Srinivasan, A.; Srikanth, A.; Indrajit, H.; Narasimhan, V. A novel approach for road accident detection using DETR algorithm. In Intelligent Data Science Technologies and Applications, Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Intelligent Data Science Technologies and Applications (IDSTA 2020), Valencia, Spain, 19–22 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.W.; Yang, D.; Feng, T.W.; Fu, J.J. MDFD2-DETR: A Real-Time Complex Road Object Detection Model Based on Multi-Domain Feature Decomposition and De-Redundancy. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 10, 4343–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, W.; Gu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T. Application of combining YOLO models and 3D GPR images in road detection and maintenance. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Luo, W. PDNet: Improved YOLOv5 nondeformable disease detection network for asphalt pavement. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 5133543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuvo, M.M.R.; Dey, A.; Rahman, M.O. A YOLO-Based Framework for Road Sign Detection and Recognition in the Context of Bangladesh. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Computing, Applications and Systems (COMPAS 2024), Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Computing, Applications and Systems (COMPAS), Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 25–26 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, X. YOLO-RDD: A road defect detection algorithm based on YOLO. In Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design. International Conference, Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), Tianjin, China, 8–10 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1695–1703. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing System 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.N.; Guan, J.; Wu, W.; Yu, Z.; Yan, R. 2d-tpe: Two-dimensional positional encoding enhances table understanding for large language models. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 2450–2463. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, F.; Liu, J.; Liu, G. Depth-wise separable convolutions and multi-level pooling for an efficient spatial CNN-based steganalysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 15, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, K.; Nakka, K.; Fua, P.; Salzmann, M. Detecting the unexpected via image resynthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 2152–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, D.; Maeda, H.; Ghosh, S.K.; Toshniwal, D.; Sekimoto, Y. RDD2020: An annotated image dataset for automatic road damage detection using deep learning. Data Brief. 2021, 36, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohankumar, C.E.; Manikandan, A. Decentralized traffic management with Federated Edge AI: A reinforced transnet model for real-time vehicle object detection and collaborative route optimization. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Style | Sample Size | Definition and Typical Scenarios |

|---|---|---|

| Construct | 572 | Temporary construction zones including warning signs, and workers in safety gear (reflective vests, helmets) |

| Matter | 484 | Foreign objects on road surface such as fallen trees, rocks, and other obstacles that pose collision risks |

| Person | 1081 | pedestrians in unauthorized road areas where their presence poses safety risks |

| Fire | 1173 | Fire-related incidents including vehicle combustion, roadside fires, and smoke that affect visibility |

| Spill | 1471 | Scattered items and materials on road surface including plastic bags, tires, packaging materials, and other dispersed objects that affect driving safety |

| Bad state | 1140 | Road infrastructure damage such as potholes, cracks, and collapsed sections |

| Illicit vehicles | 1283 | Non-motorized and unauthorized vehicles in dangerous or restricted road areas, particularly tricycles and bicycles |

| Animal | 4349 | Animals on roadway, particularly those frequently appearing on highways including pigs, cattle, sheep, horses, dogs, and other livestock or domestic animals that create collision hazards |

| Traffic accident | 2655 | Vehicle collision incidents including crashes and overturned vehicles |

| Total | 14,208 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| epochs | 200 |

| batch size | 4 |

| imgsz | 640 × 640 |

| weight decay | 0.0005 |

| learning rate | 0.01 |

| momentum | 0.937 |

| weight decay | 0.0005 |

| warmup epochs | 3.0 |

| Methods | P/% | R/% | mAP@0.5/% | F1/% | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yolov5 [14] | 93.4% | 93.6% | 96.6% | 93.4% | 117.08 |

| Yolov8 [15] | 91.8% | 88.6% | 93.5% | 90.2% | 90.61 |

| Yolov10 [16] | 93.4% | 90.6% | 95.8% | 92.0% | 62.25 |

| RT-DETR [18] | 90.6% | 91.1% | 92.9% | 90.8% | 46.32 |

| Yolo11 [17] | 90.1% | 87.8% | 93.3% | 88.9% | 78.68 |

| Proposed | 96.2% | 96.5% | 98.2% | 96.3% | 54.14 |

| Methods | PMA | AVD | P/% | R/% | mAP50/% | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yolov5 | 93.4% | 93.6% | 96.6% | 93.4% | ||

| A | √ | 95.4% | 96.4% | 97.9% | 95.9% | |

| B | √ | 94.8% | 94.8% | 97.5% | 94.8% | |

| C | √ | √ | 96.2% | 96.5% | 98.2% | 96.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, M.; Zhu, Z.; Tu, R.; Lv, A.; Yu, Z. AVD-YOLO: Active Vision-Driven Multi-Scale Feature Extraction for Enhanced Road Anomaly Detection. Information 2025, 16, 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121064

Jin M, Zhu Z, Tu R, Lv A, Yu Z. AVD-YOLO: Active Vision-Driven Multi-Scale Feature Extraction for Enhanced Road Anomaly Detection. Information. 2025; 16(12):1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121064

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Minhong, Zhongjie Zhu, Renwei Tu, Ang Lv, and Zhijing Yu. 2025. "AVD-YOLO: Active Vision-Driven Multi-Scale Feature Extraction for Enhanced Road Anomaly Detection" Information 16, no. 12: 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121064

APA StyleJin, M., Zhu, Z., Tu, R., Lv, A., & Yu, Z. (2025). AVD-YOLO: Active Vision-Driven Multi-Scale Feature Extraction for Enhanced Road Anomaly Detection. Information, 16(12), 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121064