Abstract

Recent global conflicts have amplified long-standing patterns of religion-related bias and discrimination in the U.S. The continuing war on Gaza has led to bias, hostility, and violence against both Muslims and Jews in the U.S. We present an overview of results from a new 1308-person national survey data collection gathered through NORC’s AmeriSpeak Panel with oversamples of Jews and Muslims. Our findings reveal important reversals, asymmetries, polarities, and solidarities in perceptions and experiences of bias among Jews and Muslims and experiences of and responses to the war among religious groups. Jews were the most likely group to report experiences of religious bias and hostility in the U.S. and the most likely to register fear about future bias, followed by Muslims, a reversal of patterns from earlier research. Jews were the most likely religious group to report experiencing an increase in religious bias or hostility after October 7, 2023. Americans reported warm feelings towards Jews, Muslims, Israelis, and Palestinians but cool feelings towards the Israeli government and Hamas, suggesting that across most religious groups, Americans demonstrate more sympathy towards religious identities when compared to national identities and political entities.

1. Introduction

Recent global conflicts and religion-related conflicts, in particular, have increased and amplified long-standing patterns of religion-related bias and discrimination in the U.S. The Israel–Palestine conflict has been a source of political and religious tension in the U.S. for decades, but the Israeli government’s ongoing decimation of Gaza and its people following the Hamas-led terrorist attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 is correlated with increased bias, hostility, and violence against both U.S. Muslims and Jews. From assaults on Muslim-Americans, such as the murder of 6-year-old Wadee Al Fayoumi in Illinois (Yan et al. 2023), to attacks on Jewish-Americans, such as the fire-bombing of a pro-Israeli rally in Colorado (Garcia et al. 2025), religion-related hostility targeted towards American Muslims and American Jews has erupted into violence on the streets.

Religion in the U.S. has played a significant role in responses to the war. There has been some evidence of religious tribalism (Silver 2025). Conflict within religious groups has also grown, such as between Evangelical and Mainline Protestant Christians (Doucet 2023). Some have joined in protests for Palestine or Israel, while others have remained on the sidelines. Furthermore, with increased real-time information on hostilities in the Middle East through social media, many have reported heightened stress and negative impact on their mental health. And there has been real debate about whether religion is even a central factor in the conflict (Walters 2024).

Despite these disturbing developments, we have little systematic information on the status of religious bias and hostility towards Jews and Muslims in the U.S. since 7 October 2023. Furthermore, we know less about how different U.S. religious groups are responding to the war, how the war impacted them, and the extent of religious bias and hostility towards Jews and Muslims in the midst of the war. Here we present an initial overview of results from the 2024 Boniuk Institute Religion and Social Issues Survey with oversamples of Jewish and Muslim Americans on the status of religious bias and hostility towards these groups in light of October 7 and the ensuing war on Gaza and its response. We examine religious differences across several measures of affect, experiences and perceptions of religious bias and hostility, and attitudes toward and responses to the war in Gaza.

1.1. Religious Bias and Hostility in the U.S.

There is both statistical and anecdotal evidence that the United States’ changing religious landscape is producing an increase in religion-related crime and violence. In analyzing the 2004 National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), Wilson (2014) found that 10 percent of reported criminal victimizations with a bias or hate motivation were directed towards the victim’s religion. Her analysis revealed that this percentage had increased to 25 percent in 2011 and 28 percent in 2012. Between 2015 and 2019, in 10 percent of violent hate crimes and 48 percent of property hate crimes, victims perceived that the offender was motivated by the victim’s religion (Kena and Thompson 2021). Official statistics show how religion-related hate crimes have increased over the past fifteen years (FBI 2024; Government Accountability Office 2019; Statista Research Department 2024), and independent research has demonstrated the prevalence of religious bias and hostility, particularly towards Muslims and Jews living in the U.S. (Scheitle et al. 2023; Scheitle and Ecklund 2020).

Researchers have examined religion-related attitudes in several ways, which provide different angles on the public’s bias or favorability towards different religious groups. From 2014–2023, Pew examined Americans’ attitudes towards religious groups using feeling thermometers and favorability ratings, finding that the public maintained relatively warm or positive attitudes toward Jews, Catholics and mainline Protestants, but cooler or more negative feelings toward Mormons, Muslims and atheists (Masci 2019; Mitchell 2017; Tevington 2023; Wormald 2014).

Scholars have also examined experiences of religion-related bias and hostility and individuals’ fear of encountering bias in the future. In a 2019 study, Ecklund, Scheitle, and colleagues found that past experiences of religious discrimination increase fear of future victimization, and that Jewish and Muslim adults report the highest levels of fear of future religious victimization (Scheitle et al. 2023). They attribute this heightened fear among Jews and Muslims to “distal sources of fear” related to memory of the Holocaust or anti-Muslim hate crimes following 9/11. The problem is that the ability of social scientists and policy makers to examine religion-related bias crime is hamstrung by the quality of available data. Consider Wilson’s (2014) NCVS, which contains a series of questions asking whether a crime victim believes that she was victimized due to her religion, race, or gender, as well as a series of other characteristics. For most of these perceived bias-crime types, the NCVS also asks for the demographics of the victim. This means that it is possible to know, for example, whether a person who is claiming victimization due to race is white, black, or some other race. When it comes to religion, however, the NCVS does not ask for the religious affiliation or identity of the victim.

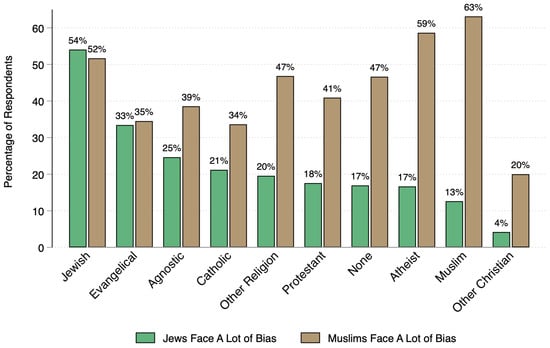

There have also been changes in the levels of bias and discrimination towards Jews and Muslims in the U.S. over the past several years. A 2024 study found that 40% of Americans said that Jews face a lot of discrimination, up from 20% in 2021, and 44% said that Muslims face a lot of discrimination, which was up only 5 percentage points from 2021 (Alper et al. 2024). The study also found asymmetry in Jews’ and Muslims’ perceptions against their own groups. Over half of Jews (57%) and two-thirds (67%) of Muslims said that there is a lot of discrimination towards Muslims in the U.S., but only 17% of Muslims, compared to 72% of Jews, say that there is a lot of discrimination towards Jews in the U.S. Perceptions of discrimination against Jews and Muslims have declined since 2024; 34% say that there is a lot of discrimination against Muslims and 30% say that there is a lot of discrimination against Jews (Pew Research Center 2025b).

1.2. Religious Dimensions of the Gaza War’s Impact in the U.S.

Religion-related conflicts (both global and national) often stir religion-related tensions and bias in the U.S. The impact of the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Centers on increased discrimination towards Muslims in the U.S. is well-documented (Byers and Jones 2007; Peek 2011). Although focusing on France, Olsson’s (2024) study similarly shows how terror attacks—defined as sudden, large-scale events—affect the activation and expression of implicit bias toward Arab Muslims. Furthermore, when tensions between Israel and Palestine escalate, there are often increases in antisemitic hate crimes in the U.S. (LaFreniere Tamez et al. 2024).

Religious divisions over the Gaza war in the U.S. illustrate Burawoy’s (2025) framework showing how “settler colonialism” creates zero-sum conflict dynamics where deeply held religious beliefs become so “historically entrenched” and “psychologically immoveable” that they function as weaponized tools in domestic political discourse rather than sources of moral guidance. These positions fuel escalating religious bias toward Jewish and Muslim Americans, with each community’s suffering used to justify further polarization.

Global religion-related conflicts also have an impact on people’s mental health. Following 9/11 and the anti-Islamic backlash, some U.S. Muslims reported “feeling less safe” in the U.S. and exhibiting PTSD symptoms (Abu-Ras and Suarez 2009; Scheitle et al. 2023). These events are likely to trigger higher frequencies of microaggressions in the U.S. that are associated with lower quality of life, poorer mental health and greater emotional problems (Douds and Hout 2020). In response to global religion-related conflicts, many respond with advocacy and activism. Following 9/11, American Muslims were more likely to become politically aware and engaged (Ayers and Hofstetter 2008), and Muslim Arab-Americans were especially likely to protest the anti-Muslim backlash following 9/11 (Santoro and Azab 2015). Here we ask how Americans see the relationship between the Israel–Palestine conflict and perceptions of feelings towards and discrimination against Muslims and Jews. We use a new survey-based data collection to answer these questions.

2. Data

Data comes from the 2024 Boniuk Institute Religion and Social Issues Survey fielded with funding from the Boniuk Institute for the Study and Advancement of Religious Tolerance at Rice University. Survey responses were collected from 1 July to 24 July 2024, with the purpose of measuring the public’s attitude toward current issues around science, politics and religion. In this paper, we are interested in individuals’ perspectives on the experiences of Jewish and Muslim people in the U.S. and the Israel–Palestine Conflict. The target population was sampled from NORC’s AmeriSpeak Panel, a large probability-based panel designed to be representative of the U.S. household population. Samples drawn from probability-based panels have been utilized in several top studies (e.g., Pedulla and Thébaud 2015), recognizing the more accurate estimates from these samples than those from random-digit dialing or non-probability online samples (Chang and Krosnick 2009). Currently, the AmeriSpeak panel has 54,001 members residing in 43,000 households.

A stratified sample of 4592 individuals from the general population aged 18 years or older was selected with oversamples of the Jewish and Muslim populations. These groups were selected based on the purpose of the survey and contemporary global events, such as the Israel–Palestine conflict. The survey was conducted in English and online, either through the password-protected AmeriSpeak Mobile App, web portal or by following the link contained in the e-mail invitation. A total of 1308 individuals responded (including 512 religious or cultural Jews and 81 Muslims), with a completion rate of 28.5% based on the American Association for Public Opinion Research guideline RR5, which considers only completed surveys (AAPOR 2023; Callegaro and DiSogra 2008).1 All results have been weighted to be nationally representative and account for the probability of selection and non-responses. The analysis conducted in this paper is not meant to be exhaustive. In some way, we refer to essential contours of the data that will be important for future analyses to build upon. Regardless, we hope readers gain insights from this novel data and by comparing results to previous studies, how the landscape has changed regarding politics and religion in the U.S.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of the respondents in our sample. Percentages in the table are weighted to represent the general population. Due to oversampling, 24% of the sample is Jewish (n = 313), and 6.2% of the sample is Muslim (n = 81), though both Jews and Muslims represent about 1% of the U.S. population (Pew Research Center 2025a).2 All Christian groups together represent around 60% of the sample, and nones, atheists and agnostics are around 27% of the sample. Just less than 40% of the respondents reside in the Southern United States and almost a quarter in the Western United States. Thirty-eight percent of the sample has a high school degree or less while only 15% of respondents have a postgraduate degree. A third of respondents never attend religious services and just less than a quarter attend almost weekly or more. Respondents are relatively equally split across income levels with 30% earning $100,000 or more per year.

Table 1.

Demographics.

3.2. Affect Towards Religious Groups

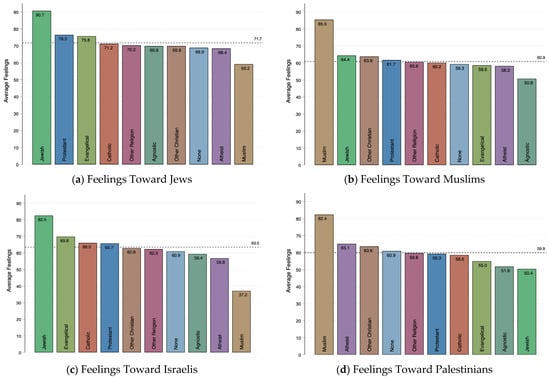

Figure 1 displays respondents’ averaged feelings toward Jews, Muslims, Israelis, Palestinians, the Israeli government, and Hamas (full results in online appendices).3 Overall, on a 100 point scale where values above 50 are warm and below 50 are cold, Americans tend to have warm feelings toward Jews (71), Muslims (60), Israelis (63) and Palestinians (59), and cold feelings toward Hamas (30) and the Israeli government (45). To examine these feelings across different religious groups in the U.S., we first look at which groups are the recipients of the warmest and coolest feelings towards the groups directly involved in or associated with the war. Nearly all religious groups are warmest towards Jews and coolest towards Hamas. Muslims, in contrast, are warmest towards Muslims (85) and coolest towards the Israeli government (23).

Figure 1.

Average Feelings Toward Identity Groups. Data comes from the 2024 Boniuk Institute Religion and Social Issues Survey. The figure displays the average feelings toward certain identity groups—(a) Jews, (b) Muslims, (c) Israelis, (d) Palestinians, (e) the Israeli government, and (f) Hamas—by religious tradition, weighted to represent the general population. The dashed line and corresponding value represent the weighted average feelings toward specific identity groups from the entire sample. Feelings are on a scale of 0 (cold) to 100 (warm). (Data in Table S1).

Next, we examine which religious groups are warmest or coolest towards the groups involved or associated with the war. As expected, Jews are the warmest of all religious groups to Jews (91), Israelis (83), and the Israeli government (56) and coolest of all religious groups to Palestinians (50), and Hamas (10). Notably, a large minority of Jewish Americans are cool towards the Israeli government. Muslims are warmest of all religious groups towards Muslims (85), Palestinians (82), and Hamas (42) and coolest of all religious groups to Jews (59), Israelis (37), and the Israeli government (23). The one deviation from this pattern of opposing affect is with regard to how Jews feel about Muslims. Jews are relatively warm towards Muslims (64), more so than they are towards Evangelicals (59) and Atheists (58), and agnostics are coolest towards Muslims (51). This suggests within the U.S. that there is some asymmetry in feelings about groups perceived to be associated with the war. Namely, U.S Jews hold favorable feelings towards Muslims in general, despite cooler feelings towards Palestinians specifically.

Interestingly, there was also asymmetry in the response patterns to these items, indicating differential ambivalence. Jewish respondents were most likely not to register their feelings about Hamas. Of the 301 respondents who skipped this question, 30% are Jews, 14% are Evangelicals and 11% are Nones. All other religious traditions compromise less than 10% of the skipped respondents. Compare this to the characteristics of the 123 respondents who skipped the feeling thermometer for the Israeli Government—18% are Nones, 15% Evangelicals and 13% Muslims. These findings suggest that a sizeable percentage of Evangelicals and Nones were reticent to register their feelings about Hamas or the Israeli Government, and a sizeable percentage of Muslims are reticent to register their feelings about the Israeli Government. Most significantly, that Jewish respondents were twice as likely not to register their feelings about Hamas points to some underlying tensions and complexities of how U.S. Jews are experiencing the war (Alper 2024).

3.3. Experiences of Bias

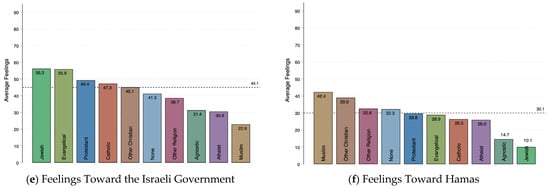

Figure 2 presents the percentage of each religious group who have ever experienced religious bias or hostility, have experienced an increase in religious bias or hostility since October 2023, or are concerned about experiencing religious bias or hostility in the future (full results in online appendices). We found that nearly 75% of Jewish respondents and 56% of Muslim respondents have ever experienced religious bias or hostility. This suggests a reversal of patterns from before the war. In a 2019 survey, 68% of Jews and 81% of Muslims said that they experienced interpersonal hostility from others due to their religion in the past year, and Muslims were four times more likely than Jews to have ever experienced institutional religious discrimination (Scheitle and Ecklund 2020). We also found that nearly a quarter of Jews (23%), and 16% of Muslims reported an increase in religious bias or hostility since October 7th.

Figure 2.

Experiences of Religious Bias. Data comes from the 2024 Boniuk Institute Religion and Social Issues Survey. (a) The weighted percentage of those who have experienced an increase in religious bias or hostility in the 9 months preceding June 2024, i.e., since October 2023. (b) The percentage of respondents who have ever experienced religious bias or hostility since they were 16 years old. (c) The percentage of those who are somewhat or very concerned about future religious bias or hostility. All figures are shown by religious tradition and weighted to represent the general population. The dashed line and corresponding value represent the weighted percentage of the entire sample. (Data in Table S2).

This heightened concern and experience of religious bias among Jews and Muslims is also apparent when we asked about their fear of future religious bias or hostility. We found that 75% of Jews and 56% of Muslims are concerned about experiencing religious bias or hostility in the future. This is also a reversal of previous research on fear of future religious bias. Scheitle et al. (2023) found in a 2019 study that Muslims reported the most fear of future victimization, followed by Jewish respondents. Our findings suggest that this ordering has reversed, where fear of future religious hostility is more prominent among Jews when compared to Muslims.

Comparing the experience of Muslims and Jews to other groups also puts these patterns in stark relief. Only respondents from other non-Christian religions report similar levels of past experience of religious bias or hostility (56%). For all other groups, between 10 and 32% report past religious bias. Between 1 and 8% of all other groups report an increase in religious bias since October 7th, and 8–38% report fear of future religious bias.

3.4. Impact of and Response to the War

We next look at how different religious groups have responded to and experienced the war. Table 2 shows the percent by religious tradition who have experienced a negative impact on their mental health due to the war and have sought counseling for this negative impact. We also report percent by religious tradition who see religion as the most or a very important factor in the war. And finally, we report percent by religious tradition who think it is very important to take a side in the war, and who have participated in a pro-Palestine or pro-Israel protest.

Table 2.

Responses to the Israel–Palestine Conflict.

Overall, 20% of the U.S. say that the war has had a negative impact on their mental health and 7% have sought counseling as a result. Breaking this down by religious tradition, Muslim (63%) and Jewish (56%) respondents were most likely to say that the war had a negative impact on their mental health. Individuals who are Protestants but not Evangelicals (12%) and individuals who have no religion (nones) (15%) were least likely to say the war has had a negative impact on their mental health. Across religious traditions, we find a statistically significant percentage of only Evangelical (15%) and Jewish (6%) respondents who sought counseling for this negative impact, but this is likely due to sub-sample size constraints—only respondents who indicated that the war had a negative impact were asked whether they had sought counseling. Overall, the war has had the greatest negative impact on Muslim and Jewish Americans’ mental health, and a small percentage of any religious group sought counseling in response to the negative impact on mental health.

Over half of Americans (57%) say that religion is a very important factor in the war, but just 11% say that it is very important to take a side. Interestingly, atheists are most likely to say that religion is the most or a very important factor in the war (78%), followed by Jewish respondents (64%) and non-evangelical Protestants (65%). Only 42% of Muslims see religion as the most or a very important factor in the war, the lowest percentage along with Nones (43%). In terms of the importance of taking a side in the war, similar percentages of Jews (41%) and Muslims (42%) say that it is very important to take a side, far greater percentages than all the other groups. Importantly, however, less than half of Jews and Muslims say that it is very important to take a side.

Finally, very few Americans have participated in protests—3% have protested for the Palestinian cause and 1% for the Israeli cause. Surprisingly, atheists were most likely to participate in pro-Palestinian protest (13%) along with Muslims (11%), suggesting a degree of solidarity between Atheists and Muslims previously unrecognized. Jews were most likely to participate in pro-Israel protests, followed by Evangelicals (2%), as might be expected given long-standing support of Israel among Evangelicals.

3.5. Perceptions of Bias

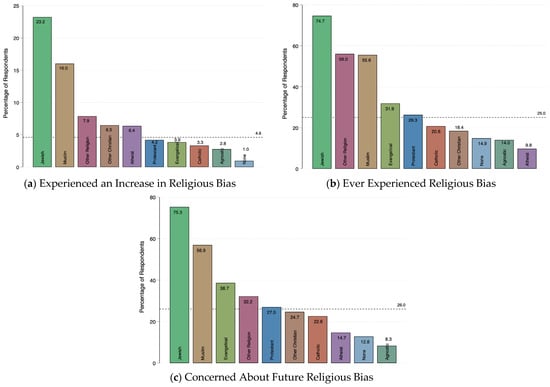

Finally, we examine the perception of bias towards Jews and Muslims in the U.S. Figure 3 shows these percentages across religious traditions (full results in online appendices). Overall, a greater percentage of the public thinks that Muslims face a lot of bias (40%) compared to Jews (21%). Jews are most likely to say that Jews in the U.S. face a lot of bias, (54%), followed by 33% of Evangelicals who say that Jews in the U.S. face a lot of bias, and 25% of Agnostics. Looking at perception of bias towards Muslims, 63% of Muslims and 59% of atheists think that Muslims face a lot of bias in the U.S. Four other groups perceive a lot of bias against Muslims above the national average (39%)— Jews (51%), religious nones (47%), members of other religions (47%), and non-Evangelical Protestants (41%). Muslims and Atheists report the highest percentages of perceiving a lot of bias towards Muslims, and Jews and Evangelicals report the highest percentages of perceiving a lot of bias towards Jews in the U.S. Interestingly, similar percentages of Jews and Evangelicals perceive both a lot of bias towards Jews and a lot of bias towards Muslims, whereas other groups are more asymmetrical in their perceptions.

Figure 3.

Perception of Bias Against Jews and Muslims in the U.S. Data comes from the 2024 Boniuk Institute Religion and Social Issues Survey. The figure displays the weighted percentage of respondents from each religious group who perceive that Jews/Muslims face a lot of bias in the U.S. (Data in Table S3).

4. Discussion

In this study we have explored how people relate the experiences of Jewish and Muslim people in the U.S. to the Israel–Palestine Conflict. We used a new national survey data collection gathered through NORC’s AmeriSpeak Panel at University of Chicago, with oversamples of Jewish and Muslim Americans. We replicated questions from other studies and explored as yet unanswered questions about the impact of and responses to the war in Gaza. Our findings reveal important reversals, asymmetries, polarities, and solidarities in perceptions and experiences of bias by Jewish and Muslim Americans as well as, among U.S. religious groups, experiences of and responses to the war.

Jews were the most likely group to report experiences of religious bias and hostility in the U.S. and the most likely to register fear about future bias, followed by Muslims. This is a reversal of patterns from earlier research (Scheitle et al. 2023; Scheitle and Ecklund 2020). We also found that Jewish respondents were the most likely among religious groups to report experiencing an increase in religious bias or hostility. This is consistent with earlier reports by Pew (Alper et al. 2024), although our data measures more directly individual’s experience of religious bias or hostility rather than their perception of the group’s experience. Other studies which asked about religious discrimination in different contexts have found that Muslims reported higher levels around this time (Ikramullah 2024), suggesting that how religious bias, hostility, and discrimination is measured has important consequences for estimates of relative prevalence. Timing also matters. Our study was fielded in July of 2024, and these others were fielded at the beginning of 2024, nearly six months prior. It is possible that the escalation of the war following the first failed ceasefire in May 2024 may have led to a shift in the experiences of Jewish Americans.

Other asymmetries were present as well. Nearly all groups reported the warmest feelings towards Jews in our study, consistent with other recent analysis of favorability towards Jews and Muslims (Telhami 2024). This overall greater favorability extended to Israelis, compared to Palestinians, and to the Israeli government compared to Hamas. Yet, importantly, we found that Americans are overall rather cool towards the Israeli government and Hamas, pointing to a widespread distinction between religious groups, national identities, and the political entities that seek to represent these to some extent. Only Muslim respondents registered cool or unfavorable average feelings towards Israelis. Our results suggest that across most religious groups, Americans demonstrate more sympathy towards religious identities compared to national identities and political entities.

There were other important asymmetries and polarized responses to the war and those associated with the war. Both U.S. Jews and Muslims held warmer feelings towards their own groups than toward the other, as would be expected, but Jewish respondents held the second warmest feelings towards Muslims. This is in contrast to our finding that Jewish respondents held the coldest feelings toward Palestinians. This asymmetry suggests that shared religious, as opposed to non-religious, identity with Muslims may elicit affective affinity, as some have found in ethnographic studies (Emmerich 2025), whereas ethno-political identities, e.g., Jewish and Palestinian, is linked to antipathy, as others have found (Gidley et al. 2025).

This asymmetry is also reflected in perceptions of bias towards Jews and Muslims in the U.S. Jews perceive a lot of bias towards both Jews and Muslims in the U.S., whereas Muslims mostly see a lot of bias towards their own group. This asymmetry is consistent, though slightly lower than other estimates earlier in 2024 (Alper et al. 2024), suggesting a decline in perceptions of bias towards Jews and Muslims which has been documented more recently (Pew Research Center 2025b). Interestingly, among both Jewish and Evangelical respondents, similar percentages perceived a lot of bias towards both Jews and Muslims, whereas all other religious groups demonstrated much greater sympathy for Muslims compared to Jews. The higher percentage of perceiving bias towards Jews among Jews and Evangelicals is as expected, but that these two groups are equally aware of anti-Muslim bias suggests these two groups may not perceive anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish bias in the U.S. as a zero-sum game. Further research is needed to explore these findings and their meaning for religious polarization in the U.S.

An important aspect of our study examined the impact of the war on peoples’ mental health, finding a greater negative impact on Jewish and Muslim Americans. This negative impact is exacerbated by the low percentage of respondents who sought out therapy for the negative mental health consequences caused by the war, which was lower for Muslims compared to Jews. Although we were not able to fully explore the causes of this disparity, or the extent to which Muslim or Jewish respondents relied on their religious communities rather than professional therapists to address mental health issues, our findings illustrate the burden such international conflicts place on religious individuals here in the U.S.

The public and pundits debate the extent to which the Israel–Palestine conflict is a religious conflict, or whether it is primarily about land, politics, or other issues. Our study provides a unique window into this question by posing the question of religious conflict directly. We were surprised to see that a great majority of atheists see the war in Gaza and Israel as being largely about religion. Although there is significant research dispelling the stereotype of atheists as being hostile to religion (Ecklund and Johnson 2021), these findings suggest that there still may be the perception among atheists in the general public that religion leads to conflict. Further research could explore how atheists understand the link between religion and global conflict and the extent to which different religious groups see other factors as important to the Israel–Palestine conflict.

Another strength of our study is the multiple ways we explored solidarity and polarization in relation to the war in Gaza and Israel. A surprisingly low percentage of Americans saw it as important to take a side, just slightly more than 1 in 10. Our research was conducted in July of 2024, as the Israeli military was expanding its operations in Gaza and protests were widespread. Since then, the war has expanded with Israeli attacks on other nations and regions and the destruction and decimation of Gaza and its people has amplified. We might expect that the percentage of those feeling that it is very important to take a side would be higher now.

An interesting finding regarding demonstrated solidarity was the participation of atheists in pro-Palestinian protests. This shows a somewhat surprising and conflicted expression of solidarity with American Muslims. Atheists were most likely to see religion as an important part of the war, while less than half of Muslims did. Though our study found solidarity in the Palestinian cause, we found very different understandings of the role of religion in this cause.

There are some limitations to our study. First, we fielded our survey in July of 2024 and much has happened in the war and in the U.S. since then. Such changes have most certainly continued to shape anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish bias as well as experiences of and responses to the war. Hence, findings in this paper are specific to contemporary events leading up to the date of the survey. Future research could improve upon this study by examining protest participation in the past year, experiences of and fear of anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish bias, and attitudes towards and the impact of the war, given its dramatic escalation and expansion. Additionally, although we oversampled for both Jewish and Muslim respondents, research with a larger subsample of Muslim respondents would enable a more robust analysis.

One further area of research is in comparison to European contexts, where the relationship between global conflicts, national politics, and attitudes towards Jews and Muslims differ. Like in the U.S., Jews, when compared to Muslims, are generally seen more favorably by the general population in Europe (Wike et al. 2019), and like the U.S., Jews in Europe are concerned about potential links between anti-Zionism and anti-Jewish bias (Mayer and Tiberj 2022; DellaPergola 2020). However, some work suggests that attitudes towards Jews and Muslims in Europe are more strongly shaped by security concerns, class conflict, and national differences in the relationship between religion and the state. These factors may mean that attitudes towards Jews and Israel/Israelis and towards Muslims/Hamas/Palestinians may be more linked than in the U.S. (Gidley et al. 2025).

5. Conclusions

Global religion-related conflicts have implications for religious groups in the U.S. They shape perceptions and experiences of religious bias, and they potentially increase religion-related polarization and hostility. The Israel–Palestine conflict has been one of the most consequential for religious conflict in the U.S., and the recent war in Gaza has amplified tensions, discrimination, and victimization. Our study sheds light on these developments and highlights the ways religious groups are experiencing and responding to the war and to its impact on Jewish and Muslim Americans. We provided here important contemporary systematic information on the status of religious bias and hostility in the U.S., specifically toward Jews and Muslims. By examining religious differences across measures of affect, we find that Americans generally feel warm toward religious identities and groups (Jews, Muslims, Israelis, and Palestinians) but cool toward associated political entities (Israeli government and Hamas). We also find a reversal in past patterns in that Jews are the most likely group to report experiences of bias, hostility, and fear for the future, followed by Muslims. Our findings also indicate that similar percentages of Jews and Evangelicals perceive both a lot of bias towards Jews and Muslims, whereas other groups are more asymmetrical in their perceptions, with most perceiving Muslims to face a lot of bias. Lastly, we find that both Jewish and Muslim Americans experienced a significant negative impact on their mental health due to the conflict.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rel16121552/s1, Table S1: Data for Figure 1—Average Feelings toward Certain Groups; Table S2: Data for Figure 2—Experiences of Religious Bias or Hostility; Table S3: Data for Figure 3—Perception of Bias towards Jews and Muslims.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.H.E. and K.G.; methodology, E.H.E., K.G. and E.v.d.M.; formal analysis, E.H.E., K.G. and E.v.d.M.; data curation, E.H.E., K.G. and E.v.d.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.H.E., and K.G.; writing—review and editing, E.H.E., K.G. and E.v.d.M.; visualization, E.H.E., K.G. and E.v.d.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Boniuk Institute for the Study and Advancement of Religious Tolerance at Rice University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset presented in this article is not readily available because the data are part of ongoing studies. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NCVS | National Crime Victimization Survey |

Notes

| 1 | The RR5 rate of 28.5% falls within the current typical range of 20–30% for online surveys. Our response rates according to the RR3 standards, which considers partial interviews, is 22.3%. This RR3 rate is above the 10% to 20% range for individual client surveys based on the AmeriSpeak Panel (de-pending on specific study parameters such as target population, survey length, time in the field, and salience of subject). The response rates consider panel recruitment rate, panel retention rate, and survey participation rate. |

| 2 | The weighted percentage of Muslims in our sample is larger than the true population percentage of 1% because the Muslim subsample size was too small for NORC’s raking method of generating weights, and thus the general population estimate of Muslims is due weighting based on their other demographics, not based on religion. |

| 3 | These and all following analyses include probability weights to match the general population. |

References

- AAPOR. 2023. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys (No. 10). Available online: https://aapor.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Standards-Definitions-10th-edition.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Abu-Ras, Wahiba M., and Zulema E. Suarez. 2009. Muslim men and women’s perception of discrimination, hate crimes, and PTSD symptoms post 9/11. Traumatology 15: 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, Becka A. 2024. How U.S. Jews are experiencing the Israel-Hamas war. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/04/02/how-us-jews-are-experiencing-the-israel-hamas-war/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Alper, Becka A., Laura Silver, and Besheer Mohamed. 2024. Rising Numbers of Americans Say Jews and Muslims Face a Lot of Discrimination. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/2024/04/02/rising-numbers-of-americans-say-jews-and-muslims-face-a-lot-of-discrimination/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Ayers, John W., and C. Richard Hofstetter. 2008. American Muslim Political Participation Following 9/11: Religious Belief, Political Resources, Social Structures, and Political Awareness. Politics and Religion 1: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawoy, Michael. 2025. Why and how should sociologists speak out on Palestine? The Sociological Review 73: 249–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, Bryan D., and James A. Jones. 2007. The Impact of the Terrorist Attacks of 9/11 on Anti-Islamic Hate Crime. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice 5: 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, Mario, and Charles DiSogra. 2008. Computing Response Metrics for Online Panels. Public Opinion Quarterly 72: 1008–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Linchiat, and Jon A. Krosnick. 2009. National Surveys Via Rdd Telephone Interviewing Versus the Internet. Public Opinion Quarterly 73: 641–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 2020. Jewish Perceptions of Antisemitism in the European Union, 2018: A New Structural Look. Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism—ACTA 40: 20202001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, Isabeau. 2023. ‘It’s impossible to celebrate’: Gaza war opens fissures among US Christians. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/24/us-christians-diverge-sharply-gaza-war (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Douds, Kiara, and Michael Hout. 2020. Microaggressions in the United States. Sociological Science 7: 528–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard, and David R. Johnson. 2021. Varieties of Atheism in Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerich, Arndt. 2025. Jewish-Muslim Friendship Networks: A Study of Intergenerational Boundary Work in Postwar Germany. Comparative Studies in Society and History 67: 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FBI. 2024. Hate Crime in the United States Incident Analysis. FBI Crime Data Explorer. Available online: https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/hate-crime (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Garcia, Evan, Patrick Wingrove, and Rich McKay. 2025. Colorado fire-bomb suspect planned attack for a year, prosecutors say. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/us/colorado-attack-suspect-charged-with-assault-use-explosives-2025-06-02/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Gidley, Ben, Samuel Sami Everett, Elodie Druez, Alyaa Ebbiary, Arndt Emmerich, Dekel Peretz, and Daniella Shaw. 2025. Off and on stage interactions: Muslim-Jewish encounter in urban Europe. Ethnicities 25: 235–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Accountability Office. 2019. Religious-Based Hate Crimes: DOJ Needs to Improve Support to Colleges Given Increasing Reports on Campuses. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-6 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ikramullah, Erum. 2024. American Muslims, Especially Students, Most Likely to Experience Religious Discrimination. ISPU. Available online: https://ispu.org/ceasefire-poll-3/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Kena, Grace, and Alexandra Thompson. 2021. Hate Crime Victimization, 2005–2019 (No. 300954; NCJ). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/hcv0519_1.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- LaFreniere Tamez, Hope D., Natalie Anastasio, and Arie Perliger. 2024. Explaining the Rise of Antisemitism in the United States. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masci, David. 2019. In U.S., familiarity with religious groups is associated with warmer feelings toward them. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/10/31/in-u-s-familiarity-with-religious-groups-is-associated-with-warmer-feelings-toward-them/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Mayer, Nonna, and Vincent Tiberj. 2022. Jews and Muslims in Sarcelles. In Jews and Muslims in Europe. Between Discourse and Experience. Edited by Ben Gidley and Samuel Sami Everett. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Travis. 2017. Americans Express Increasingly Warm Feelings Toward Religious Groups. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/02/15/americans-express-increasingly-warm-feelings-toward-religious-groups/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Olsson, Filip. 2024. Implicit Terror: A Natural Experiment on How Terror Attacks Affect Implicit Bias. Sociological Science 11: 379–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedulla, David S., and Sarah Thébaud. 2015. Can We Finish the Revolution? Gender, Work-Family Ideals, and Institutional Constraint. American Sociological Review 80: 116–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, Lori A. 2011. Behind the Backlash: Muslim Americans After 9/11. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2025a. Religious Landscape Study. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religious-landscape-study/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Pew Research Center. 2025b. How Much Discrimination Do Americans Say Groups Face in the U.S.? Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2025/05/20/how-much-discrimination-do-americans-say-groups-face-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Santoro, Wayne A., and Marian Azab. 2015. Arab American Protest in the Terror Decade: Macro- and Micro-Level Response to Post-9/11 Repression. Social Problems 62: 219–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheitle, Christopher P., and Elaine Howard Ecklund. 2020. Individuals’ Experiences with Religious Hostility, Discrimination, and Violence: Findings from a New National Survey. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 6: 237802312096781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheitle, Christopher P., Bianca Mabute-Louie, Jauhara Ferguson, Emily Hawkins, and Elaine HowardEcklund. 2023. Fear of Religious Hate Crime Victimization and the Residual Effects of Anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. Social Forces 101: 2059–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, Laura. 2025. How Americans view Israel and the Israel-Hamas war at the start of Trump’s second term. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/04/08/how-americans-view-israel-and-the-israel-hamas-war-at-the-start-of-trumps-second-term/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Statista Research Department. 2024. Religions most commonly targeted by hate crimes U.S. 2023. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/737660/number-of-religious-hate-crimes-in-the-us-by-religion/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Telhami, Shibley. 2024. Prejudice toward Muslims is highest among all religious and ethnic groups. Brookings. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/prejudice-towards-muslims-is-highest-among-all-religious-and-ethnic-groups/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Tevington, Patricia. 2023. Americans Feel More Positive Than Negative About Jews, Mainline Protestants, Catholics. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2023/03/15/americans-feel-more-positive-than-negative-about-jews-mainline-protestants-catholics/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Walters, James. 2024. Understanding the contested religious histories behind the Gaza War—Religion and Global Society. Religion and Global Society—Understanding Religion and Its Relevance in World Affairs. Available online: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/religionglobalsociety/2024/01/understanding-the-contested-religious-histories-behind-the-gaza-war/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Wike, Richard, Jacob Poushter, Laura Silver, Kat Devlin, Janell Fetterolf, Alexandra Castillo, and Christine Huang. 2019. Minority groups. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/10/14/minority-groups/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Wilson, Meagan Meuchel. 2014. Hate Crime Victimization, 2004-2012—Statistical Tables. Journal of Current Issues in Crime, Law & Law Enforcement 8: 217. [Google Scholar]

- Wormald, Benjamin. 2014. How Americans Feel About Religious Groups. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2014/07/16/how-americans-feel-about-religious-groups/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Yan, Holly, Brad Parks, Lauren Mascarenhas, and Virginia Langmaid. 2023. A 6-year-old Palestinian-American was stabbed 26 times for being Muslim, police say. His mom couldn’t go to his funeral because she was stabbed, too. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2023/10/16/us/chicago-muslim-boy-stabbing-investigation (accessed on 16 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).