Abstract

Iridoschisis is a rare condition defined as a separation of the anterior iris stroma from the posterior stroma and muscle layers. In this paper, we review current data about the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical characteristics and differential diagnoses of this condition and discuss the specificity of surgical treatment of concomitant ocular diseases in iridoschisis patients. Iridoschisis may pose a challenge for both an ophthalmologist in an outpatient setting and an ophthalmic surgeon. Glaucoma, primarily angle-closure glaucoma, is the most often described condition concomitant to iridoschisis. Other ocular abnormalities found relatively often in iridoschisis patients include cataract, lens subluxation and corneal abnormalities. Special attention has been paid to potential complications of cataract surgery and prevention thereof. Beside addressing the practical aspects, we point to discrepancies and suggest topics for further investigation.

1. Introduction

Iridoschisis is a rare condition which may pose a challenge for both an ophthalmologist in an outpatient setting and an ophthalmic surgeon. The aim of this paper was to review current data about the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical characteristics and differential diagnoses of iridoschisis, and to discuss the specificity of surgical treatment of concomitant ocular diseases in patients with this condition. Moreover, conditions that may coexist with iridoschisis and require ophthalmologists’ consideration have been reviewed extensively. Special attention has been paid to potential complications of cataract surgery and prevention thereof in iridoschisis patients. Finally, the data about the occurrence, characteristics and treatment of glaucoma in patients with iridoschisis have been summarized, and possible directions for future research have been outlined.

2. Method of Literature Search

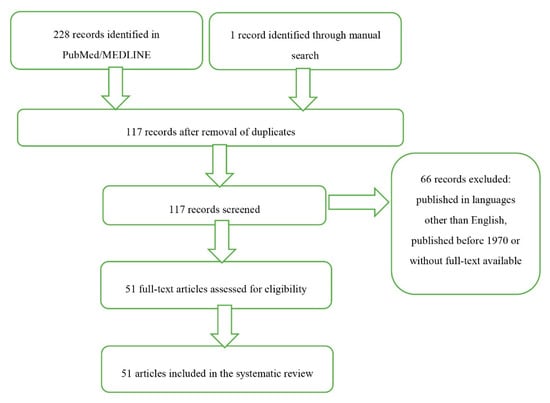

An extensive search of PubMed and MEDLINE databases has been carried out for the articles published before 1 September 2020 and containing the term “iridoschisis”. A total of 111 and 117 potentially eligible articles were identified in the two databases, respectively. Additionally, one record was identified through a manual search. The list of identified records contained 28 papers published during the last ten year, among them 22 that were eventually included in this review. While no time criterion has been applied, some papers published before 1970 were not considered, whereas other older articles were included because of their historical value. We decided to focus on the most recent data. The search was limited mostly to articles published in English, but also two French papers were included in the review for their informative value (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart documenting the selection of articles for the review.

3. Definition

Iridoschisis is a rare condition defined as a separation of the anterior iris stroma from the posterior stroma and muscle layers. In iridoschisis patients, the iris strands float in the aqueous humor and create a “shredded wheat” appearance [1]. The term iridoschisis (iris splitting) was first introduced in 1945 by Lowenstein and Foster, who reported a deep, parallel split between the anterior and posterior stromal layers of the iris [2]. However, the condition was first described as early as in 1922 by Schmitt who reported on the detachment of the anterior iris layer [3].

4. Epidemiology and Inheritance

Only about 150 cases of iridoschisis have been reported to this date, with a slight predominance of female patients over males [4].

The question whether iridoschisis is a hereditary condition or not still raises controversies. Genetic background of this condition was first postulated by Danias et al. who reported on a mother with glaucoma and iridoschisis and her asymptomatic daughter without glaucoma, but with less extensive changes in the iris documented by high-frequency ultrasound imaging [5]. Further, Mansour described a family history of iridoschisis, anterior chamber shallowing and presenile cataract. The authors mentioned above speculated that iridoschisis might be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, but these reports are scarce [4]. However, some researchers suggested that iridoschisis is not inherited but occurs sporadically, secondary to trauma, glaucoma or syphilis [2,6,7,8,9]. Other authors considered iridoschisis age-related atrophy, given that the condition is found predominantly in persons between 60 and 70 years of age [10]. As reviewed by Mansour, the mean and median ages of 131 patients with iridoschisis were 57 years and 62 years, respectively. Associated ocular findings including glaucoma, narrow angle, presenile cataract, eye trauma, cornea guttata or iris-corneal touch were found in 41%, 27%, 13%, 10%, 5% and 5% of patients, respectively [4]. However, it needs to be stressed that iridoschisis has also been reported in youths [11,12].

5. Pathophysiology

A number of theories exist regarding the pathogenesis of iridoschisis, but the exact underlying mechanism of this condition is yet to be explained.

Histopathological studies of the iris from iridoschisis patients documented tissue fibrosis and atrophy that lead to the formation of gaps between the anterior and posterior stromal layers [13].

Lowenstein and Foster suggested that iridoschisis is a consequence of either senile changes or blunt trauma or develops secondarily to glaucoma. They speculated that blunt trauma forced aqueous humor into the iris tissue destroying stroma with concomitant pigment dispersion [2,6]. Fluoroiridographic studies showed that in the affected sectors, blood flow in the vessels of the inner pupillary margin to the outer iris is normal, which implies that ischemia is unlikely a contributing factor [14]. However, some authors postulated that enhanced sclerosis of the irideal blood vessels might predispose anterior and posterior stromal layers to tear apart during dilation and constriction of the iris sphincter. Others suggested that the pathological changes observed in iridoschisis might be a consequence of an obliterative process [13]. In Bojer’s opinion, iridoschisis can be a form of essential iris atrophy in the elderly [15]. According to another hypothesis, prolonged treatment of glaucoma with miotic agents may evoke a mechanical shearing effect, which leads to tearing of the irideal stroma and resultant iridoschisis [16]. However, the latter theory is not necessarily correct, given that the miotics were used quite commonly in the past, which was not reflected by an increase in the prevalence of iridoschisis.

6. Clinical Characteristics and Diagnostic Imaging

While iridoschisis may be unilateral at its early stages, it occurs bilaterally in most cases [11] and may have a progressive character [17].

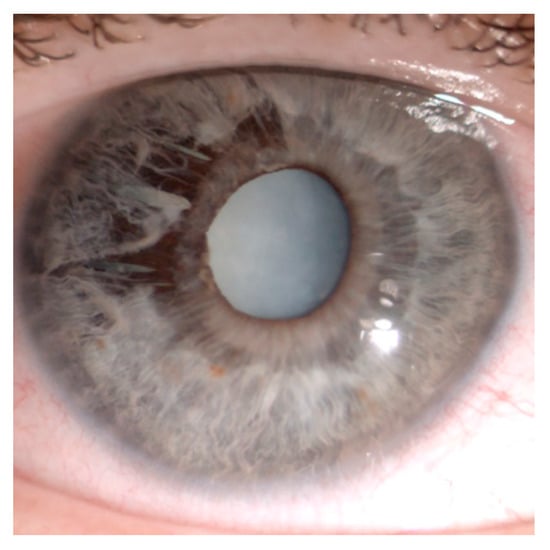

The condition is most often found in the inferior irideal quadrants, but also other parts of the iris may be affected, and sometimes the pathological process is spread across the whole iris [1,4,18,19]. According to Mansour, the most common location of the pathological process in the group of 131 patients with iridoschisis were inferior irideal quadrants (37%), followed by the inferonasal (18%), superior (9%) and inferotemporal quadrants (7%); 29% of the patients presented with diffuse iridoschisis [4]. The anterior iris stroma splits from the posterior stroma and muscle layers, and the loose ends wave in the aqueous humor of the anterior chamber, giving the iris a “shredded” appearance. (Figure 2) The posterior layer of the iris usually remains intact with the retained function of the sphincter and dilator fibers [13].

Figure 2.

“Shredded” appearance of the iris: Superotemporal iridoschisis and mature cataract. Adapted from “Iris-claw lens implantation in a patient with iridoschisis” by Pieklarz B, Grochowski E, Dmuchowska DA, Saeed E, Sidorczuk P, Mariak Z. Am J Case Rep, 2020; 21: e925234.

Corneal changes are uncommon and, if present, the degenerated corneal endothelial cells are mostly localized above the area of iridoschisis [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Visual deterioration is usually caused by glaucoma, cataract or corneal decompensation secondary to iridocorneal touch [26].

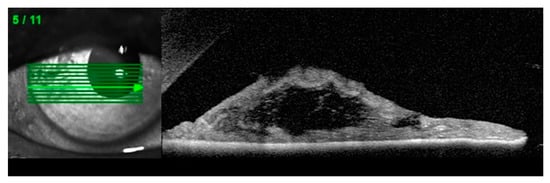

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) and Scheimpflug imaging are complementary diagnostic options in patients with suspected iridoschisis. (Figure 3) [10,27,28]

Figure 3.

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT): Disorganization of the iris stroma corresponding to iridoschisis (own source).

An unquestioned advantage of AS-OCT and UBM over Sheimpflug imaging stems from the fact that the former two are suitable for direct visualization of the angle, ciliary body and sulcus [29]. While the abovementioned imaging methods are not essential to establish the diagnosis of iridoschisis, they may add to gonioscopy in the assessment of the iridocorneal angle. Furthermore, according to some authors, UBM should be carried out in patients in whom iridoschisis is associated with angle-closure glaucoma (ACG), to differentiate between the pupillary block and plateau iris configuration [28].

7. Glaucoma and Other Associated Ocular Pathologies

Iridoschisis may coexist with an array of other ocular pathologies, and in most of the cases, it is unclear whether it occurs as a cause or effect or just by coincidence.

Glaucoma, primarily angle-closure glaucoma, is found in more than two-thirds of patients with iridoschisis [1]. A coexistence of iridoschisis with chronic open-angle glaucoma or angle recession glaucoma has been reported as well [9,19,30]. Auffarth et al. presented the case of bilateral iridoschisis coexisting with pseudoexfoliation syndrome [31]. According to one published report, iridoschisis may also coexist with capsular delamination (true exfoliation) [32]. Salmon and Murray examined 12 patients with iridoschisis and coexistent primary angle-closure glaucoma. The authors concluded that iridoschisis is an unusual manifestation of iris stromal atrophy, and results from an intermittent or acute increase in intraocular pressure [19]. However, Romano et al. analyzed six cases of iridoschisis associated with ACG and found that the former preceded the angle closure episode or at least was not its consequence [7]. Nevertheless, the results of the studies mentioned above highlight the importance of excluding primary ACG in patients presenting with iridoschisis [9].

Some published evidence suggests that iridoschisis may coexist with presenile cataract and mature cataract [1,12,33,34,35].

While rarely, iridoschisis may also be found concomitantly to lens subluxation [7,19,33,36,37,38]. Agrawal et al. reported the case of unilateral iridoschisis coexisting with ipsilateral lens subluxation. According to those authors, mechanical factors, such as lens displacement, may contribute to iridoschisis by pushing the iris forward [36]. Mutoh et al. presented the case of lens displacement into the vitreous cavity associated with ipsilateral iridoschisis. In that report, iridoschisis was associated with periocular eczema [38]. A coexistence of iridoschisis with periocular eczema has also been mentioned by other authors [36]. However, Adler and Weinberg reported on a patient with bilateral lens subluxation and unilateral iridoschisis, which puts into question the mechanical etiologic theory mentioned above [37]. Thus, we still do not have enough evidence to state whether the contact of the iris with a subluxated lens might contribute to iridoschisis or if iridoschisis is associated with zonular abnormalities that eventually result in lens subluxation.

A rare combination of iridoschisis with keratoconus has been reported as well [39,40]. The research on potential common mechanisms of these two entities suggested possible genetic predisposition. Since the posterior layers of the cornea and the iris stroma share a common embryological origin, the coexistence of keratoconus with iridoschisis may point to inter-related pathogenesis [39]. Petrovic and Kymionis reported on a patient with bilateral keratoconus who developed massive iridoschisis involving the visual axis after four penetrating keratoplasties. The patient was successfully treated with Nd:YAG punctures to obtain an iris-graft detachment [40]. Another group reported on iridoschisis in conjunction with keratoconus and compulsive eye rubbing. The authors of that report hypothesized that chronic eye rubbing might affect the iris through mechanical trauma and intraocular pressure spikes, which eventually contributed to the development of iridoschisis. Moreover, it is well known that keratoconus is strongly associated with habitual eye rubbing [41].

Corneal abnormalities secondary to iridoschisis are uncommon. Iridoschisis may be a cause of focal corneal endothelial cell loss which can be detected in specular microscopy [42]. To the best of our knowledge, there are only a few published cases of localized bullous keratopathy secondary to iridoschisis. Free floating of iris fibers was shown to result in iridocorneal touch and subsequent local endothelial decompensation [20,22,23,24,25]. Total endothelial decompensation has been reported as well [21]. In one of the cases mentioned above, iridoschisis coexisting with bullous keratopathy was found in degenerative myopic eyes. While the presence of these two conditions in a single patient might be a coincidence, the authors of that case report did not exclude the involvement of hereditary factors [22]. In another published case report, iridoschisis and bullous keratopathy were associated with nanophthalmos and microcornea [24]. However, some other authors described iridocorneal touch due to iridoschisis without resultant corneal changes [5,7,27,28].

We found one published report on Marfan syndrome concomitant to iridoschisis [7]. Coexistence of iridoschisis with congenital syphilis with or without concomitant interstitial keratitis has been reported as well. According to some authors, the pathogenesis of iridoschisis secondary to syphilis might involve immunological factors [8,9].

The authors of another interesting published case report described a patient with simultaneous bilateral nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) associated with acute ACG secondary to iridoschisis. According to the authors, elevated intraocular pressure might be the main precipitating factor for the development of NAION in their patient [26]. Iridoschisis can also coexist with plateau iris configuration [28,43]. We also found one case report on juvenile iridoschisis with incomplete plateau iris configuration and without evidence of glaucoma [27]. Swaminathan et al. reported on a patient in whom assault with an alkaline substance resulted in bilateral chemical keratoconjunctival, trabecular and lenticular damage; additionally, the patient presented with unilateral iridoschisis [44].

8. Differential Diagnoses

The diagnosis of iridoschisis is based on slit lamp examination that shows the characteristic appearance of the iris. The differential diagnoses of iridoschisis include two other principal stromal anomalies of the iris, iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome and Axenfeld–Rieger syndrome (ARS).

ICE syndrome is a group of disorders associated with the presence of abnormal corneal endothelium, accompanied by iris atrophy of various degree, secondary ACG, corneal edema and pupillary anomalies. Three clinical variants of the ICE syndrome have been described to this date: Chandler syndrome, essential iris atrophy and Cogan-Reese syndrome.

ARS is associated with anterior segment dysgenesis and systemic abnormalities. The ocular findings are typically present at birth, but progressive changes in the iris and angle defects may also be detected later in childhood. The variants of this condition include Axenfeld anomaly (prominent, anteriorly displaced Schwalbe line, with associated iridocorneal adhesions), Rieger anomaly (manifestations specific for Axenfeld anomaly plus central irideal changes) and Rieger syndrome (all ocular findings typical for Rieger anomaly plus nonocular features) [45,46].

Principal differences between the entities mentioned above and iridoschisis are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differential diagnoses of iridoschisis. Principal characteristics and distinguishing features of iridoschisis, iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome and Axenfeld–Rieger syndrome (ARS) [4,11,43,45,46].

9. Glaucoma Characteristics and Treatment in Patients with Iridoschisis

Angle-closure glaucoma or angle narrowing resulting in an acute angle closure associated with iridoschisis are usually treated with peripheral laser iridotomy to relieve the pupillary block [5,19,20,26,28,47,48]. However, some authors suggested that goniosynechialysis combined with cataract removal is superior to laser peripheral iridotomy in patients with iridoschisis complicated with closed-angle glaucoma triggered by peripheral anterior synechiae [47]. In turn, Porteous et al. described the uneventful treatment of two patients with acute angle-closure glaucoma and concomitant iridoschisis with lens extraction and IOL implantation. Postoperative IOPs in those two patients remained within normal limits without topical medication, and the angles were open on gonioscopy [35]. Finally, Shima et al. suggested that UBM should be performed whenever angle-closure glaucoma coexists with iridoschisis to differentiate between the pupillary block and plateau iris configuration, and postulated that combined trabeculotomy and cataract surgery could be a useful treatment option in persons in whom glaucoma occurs concomitantly to iridoschisis associated with plateau iris configuration [28].

Moreover, the applicability of other antiglaucoma procedures, such as trabeculectomy [9,19], implant surgery (Molteno tube) [19] or iridectomy and cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation as primary surgical treatment [19,23] has been reported in the literature.

Clinical characteristics, presentation and treatment of glaucoma concomitant to iridoschisis are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and anti-glaucoma treatment in patients with iridoschisis and concomitant glaucoma. Reports on iridoschisis without concomitant glaucoma or with insufficient information are not included. Some data are missing due to insufficient information provided in the source papers.

10. Phacoemulsification in Patients with Iridoschisis

Management of iridoschisis during cataract surgery or other anterior chamber procedures may be challenging. Snyder et al. highlighted potential risks and complications during and after the cataract surgery. First, the iris fibrils may be aspirated by the phaco probe or irrigation-aspiration probe. Second, the exposure of pigment epithelium of the iris may predispose to symptomatic photic phenomena. Third, the sphincter muscle can be damaged [49]. Lastly, according to some authors, the phacoemulsification procedure can be more challenging because of poorly dilating pupils [23,47,49,50].

According to some authors, the intraoperative circumstances during cataract procedure in a person with iridoschisis may resemble those in a patient with the floppy iris syndrome [47]. The surgery can be performed without pupil expander devices [18]. However, additional precautionary measures may be undertaken to increase the safety of the procedure. One approach is to use a dispersive viscoelastic, e.g., 3% sodium hyaluronate, to hold the iris fibrils in place [18,51]. However, it should be remembered that the viscoelastic is gradually removed with the phaco probe or aspiration-irrigation probe, and thus needs to be reinjected periodically.

Our own experiences suggest that patients with small pupils may require additional maneuvers. In such patients, the pupil can be gently stretched with two spatulas. During chopping and removal of the affected quadrant, a chopper can help move the pupil margin sideways, and an irrigation needle may play the same function during the irrigation-aspiration stage. Whichever method is used, all manipulations should be careful and limited solely to the pupillary center, and minimum required fluidic parameters need to be maintained.

Another approach is the use of iris hooks (retractors) or pupil expanders, such as Malyugin ring, Greather pupil expander or the Perfect Pupil Iris Extension System [23,31,48,52,53]. Other techniques reported in the literature involve the excision of floating iris fibers with a vitreous cutter or Vannas scissors [10,50,54]. Recently, a novel approach to the free fibril management has been proposed by Snyder et al. They applied a microcautery causing collagen contraction, shrinking the cords back to the iris surface, without the removal of any structural components [49].

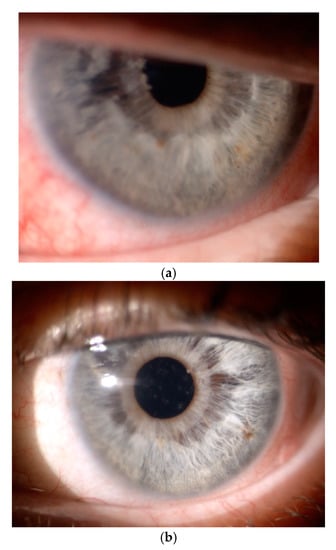

The course and outcomes of cataract surgeries in patients with iridoschisis can be negatively affected by concomitant zonulopathy with lens subluxation or luxation and bullous keratopathy [36,37,38]. In persons with iridoschisis, aphakia should be treated by implantation of scleral fixated lenses, rather than iris-claw lenses [33] (Figure 4) and all additional risks should be listed in the informed consent form.

Figure 4.

Postoperative findings in a patient with bilateral iridoschisis, associated lens subluxation, mature cataract and secondary glaucoma treated in our department. (a) Right eye following vitrectomy with lensectomy and intrascleral sutureless intraocular lens fixation (Yamane technique) on the first postoperative day. (b) Left eye following vitrectomy with lensectomy and iris-claw lens.

11. Corneal Decompensation Treatment in Patients with Iridoschisis

We found two published reports documenting the use of endothelial keratoplasty in the treatment of corneal decompensation in patients with iridoschisis [23,25]. Minezaki et al. reported on a patient with bullous keratopathy secondary to iridoschisis treated by non-Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (nDSAEK). The nDSAEK was carried out four days after phacoemulsification and iridectomy. Postoperative best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in the patient improved to 6/6 [23]. In turn, Greenwald et al. performed bilateral cataract extraction and superficial iridectomy followed by Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), achieving postoperative improvement of BCVA in both eyes to 6/6 [25].

Another treatment modality described in the literature is penetrating keratoplasty (PK) combined with cataract extraction [9,19,20,21].

Other authors described amniotic membrane transplantation as a treatment to relieve pain caused by bullous keratopathy in a patient with iridoschisis. The patient also presented with nanophthalmos, microcornea, shallowing of the anterior chamber and anterior and posterior scleral thickening. In that case, PK was considered a high-risk procedure because of the potential risk of a synechial angle closure [24].

Wesseley and Freeman suggested that iridectomy might be considered a prophylactic approach to remove disrupted iris fibers, as the latter may play a role in the development of corneal changes in selected patients [42].

12. Discussion

The prevalence of iridoschisis is difficult to estimate. It is probably underreported as no dedicated registry for this condition exists.

As shown in this review, some questions regarding iridoschisis are yet to be explained. It is still unclear whether this condition is hereditary or sporadic. Further, more consistent information about the pathophysiology of iridoschisis is required to develop an effective treatment to prevent or slow down the progression of this condition. Moreover, questions arise regarding the surgical approach to cataract in patients with concomitant iridoschisis. While a plethora of various methods have been used to manage iris fibrils and small pupil, we still lack information about the most suitable artificial lens type and material. Similarly, little is known about a preferable lens fixation method in cases with deficient capsular support and published reports on such treatment of aphakia in iridoschisis patients are scarce.

13. Conclusions

Iridoschisis is plausibly a multifactorial disease that requires particular attention from ophthalmologists and ophthalmic surgeons.

A patient diagnosed with iridoschisis should also be screened for potential glaucoma, corneal and lens abnormalities. If not yet present, one of these conditions may subsequently develop, and hence iridoschisis patients should be followed-up on a regular basis.

Ophthalmic surgeons may expect problems during and after cataract surgery in a patient with iridoschisis. Therefore, an informed consent form, listing all additional potential complications, should be signed by each patient. The perioperative risks can be mitigated with an array of methods.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gogaki, E.; Tsolaki, F.; Tiganita, S.; Skatharoudi, C.; Balatsoukas, D. Iridoschisis: Case report and review of the literature. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2011, 5, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lowenstein, A.; Foster, J. Iridoschisis with multiple rupture of stromal threads. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1945, 29, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A. Detachment of the anterior half of the iris plane. Klin Monatsbl Angenheilkd. 1922, 68, 214–215. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, A.M. A family with iridoschisis, narrow anterior chamber angle, and presenile cataract. Ophthalmic Paediatr. Genet. 1986, 7, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danias, J.; Aslanides, I.M.; Eichenbaum, J.W.; Silverman, R.H.; Reinstein, D.Z.; Coleman, D.J. Iridoschisis: High frequency ultrasound imaging. Evidence for a genetic defect? Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 80, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Loewenstein, A.; Foster, J.; Sledge, S.K. A further case of iridoschisis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1948, 32, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, A.; Treister, G.; Barishak, R.; Stein, R. Iridoschisis and angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmologica 1972, 164, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Carro, G.; Vilanova, M.; Antuña, M.G.; Cárcaba, V.; Junceda-Moreno, J. Iridoschisis associated to congenital syphilis: Serological confirmation at the 80’s. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2009, 84, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, A.J.; Hykin, P.G.; Benjamin, L. Interstitial keratitis and iridoschisis in congenital syphilis. J. Clin. Neuroophthalmol. 1992, 12, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Qian, Y.; Lu, P. Iridoschisis: A case report and literature review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesudovs, K.; Schoneveld, P.G. Iridoschisis. Clin. Exp. Optom. 1999, 82, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Aaberg, T.; Nelson, M. Iridoschisis and cataract in a juvenile patient with periocular eczema. JCRS Online Case Rep. 2017, 5, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, E.C.; Klein, B.A. Iridoschisis: A clinical and histopathologic study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1958, 46, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevalini, A.; Menchini, U.; Bandello, F.; Scialdone, A.; Brancarto, R. Aspects fluoroiridographiques de L ‘Iridoschisis. J. Fr. Ophthalmol. 1988, 11, 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bøjer, J. Iridoschisis: Essential iris atrophy. Acta Ophthalmol. 1953, 31, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, T.D.; Thomas, R.P. Iridoschisis: A case report. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1966, 62, 966–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agard, E.; Malcles, A.; El Chehab, H.; Ract-Madoux, G.; Swalduz, B.; Aptel, F.; Denis, P.; Dot, C. Iridoschisis, a special form of iris atrophy. J. Fr. Ophthalmol. 2013, 36, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Lee, J.; Hyon, J.; Kim, M.; Wee, W. A case of cataract surgery without pupillary device in the eye with iridoschisis. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 22, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, J.F.; Murray, A.D. The association of iridoschisis and primary angle-closure glaucoma. Eye 1992, 6, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.C.; Spaeth, G.L.; Krachmer, J.H.; Laibson, P.R. Iridoschisis associated with glaucoma and bullous keratopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1983, 95, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Batterbury, M.; Hiscott, P. Bullous keratopathy and corneal decompensation secondary to iridoschisis: A clinicopathological report. Cornea 2005, 24, 867–869. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.B.; Hu, Y.X.; Feng, X. Corneal endothelial decompensation secondary to iridoschisis in degenerative myopic eyes: A case report. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 5, 116–118. [Google Scholar]

- Minezaki, T.; Hattori, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Kumakura, S.; Goto, H. Non-Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty for bullous keratopathy secondary to iridoschisis. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2013, 7, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, N.J.; McDonnell, P.; Shah, P. Iridoschisis associated with nanophthalmos and bullous keratopathy. Int. Ophthalmol. 2013, 33, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, M.F.; Niles, P.I.; Johnson, A.T.; Vislisel, J.M.; Greiner, M.A. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty for corneal decompensation due to iridoschisis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2018, 9, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, A.; Reis, A.S.C.; Abucham, J.Z.; Suzuki, R.; Malta, R.F.S.; Monteiro, M.L.R. Bilateral nonarteritic anterior ischemic neuropathy following acute angle-closure glaucoma in a patient with iridoschisis: Case report. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2011, 74, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paniagua, L.; Bande, M.F. Rodríguez-Ares MT, Piñeiro A. A presentation of iridoschisis with plateau iris: An imaging study. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2015, 98, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, C.; Otori, Y.; Miki, A.; Tano, J. A case of iridoschisis associated with plateau iris configuration. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 51, 390–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Liu, T.; Liu, J. Applications of Scheimpflug Imaging in Glaucoma Management: Current and Potential Applications. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, J.F. The association of iridoschisis and angle-recession glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1992, 114, 766–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffarth, G.U.; Reuland, A.J.; Heger, T.; Völcker, H.E. Cataract surgery in eyes with iridoschisis using the Perfect Pupil iris extension system. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2005, 31, 1877–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.S.; Kang, E.Y.; Wu, W.C. Capsular delamination of the crystalline lens and iridoschisis. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 55, 343–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieklarz, B.; Grochowski, E.; Dmuchowska, D.A.; Saeed, E.; Sidorczuk, P.; Mariak, Z. Iris-claw lens implantation in a patient with iridoschisis. Am. J. Case Rep. 2020, 21, e925234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohn, D.L.; Garrett, E.E. Iridoschisis and keratoconus; report of case in a twenty-year-old man. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1954, 52, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porteous, A.; Low, S.; Younis, S.; Bloom, P. Lens extraction and intraocular lens implant to manage iridoschisis. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2014, 3, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Agrawal, J.; Agrawal, T.P. Iridoschisis associated with lens subluxation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2001, 27, 2044–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.A.; Weinberg, R.S. Iridoschisis and bilateral lens subluxation associated with periocular eczema. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2004, 30, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutoh, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Chikuda, M. A case of iridoschisis associated with lens displacement into the vitreous cavity. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2010, 4, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eiferman, R.A.; Law, M.; Lane, L. Iridoschisis and keratoconus. Cornea 1994, 13, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, A.; Kymionis, G. Massive iridoschisis after penetrating keratoplasty successfully managed with nd:Yag punctures: A case report. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, I.H.; Salmon, J.F. Iridoschisis and keratoconus in a patient with severe allergic eye disease and compulsive eye rubbing: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2016, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weseley, A.C.; Freeman, W.R. Iridoschisis and the corneal endothelium. Ann. Ophthalmol. 1983, 5, 955–964. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, K.O.; Demetriades, A.M. Juvenile iridoschisis and incomplete plateau iris configuration. J Glaucoma. 2011, 24, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, S.S.; Cavuoto, K.M.; Chang, T.C. Iridoschisis in Angle-Closure Glaucoma Associated with Alkali Burn. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, e172313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchetti, M.; Marenco, M.; Macchi, I.; Ambrosio, O.; Rama, P. Diagnosis and Management of Iridocorneal Endothelial Syndrome. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, M.B. Axenfeld-Rieger and Iridocorneal Endothelial syndromes: Two spectra of Disease with Striking Similarities and Differences. J. Glaucoma 2001, 10 (Suppl. S1), S36–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Z.; Qin, Y.; Li, G.; Shi, K. Goniosynechialysis combined with cataract extraction for iridoschisis: A case report. Medicine 2017, 96, e8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyeneche, H.G.; Osorio, J.T.; Malo, L.M. Iridoschisis in Latin America: A case report and literature review. Pan-Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 17, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, M.E.; Malyugin, B.; Marek, S.L. Novel approaches to phacoemulsification in iridoschisis. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 54, e221–e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczynski, M.; Kucharczyk, M. Phacoemulsification with Malyugin ring in an eye with iridoschisis, narrow pupil, anterior and posterior synechiae: Case report. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 23, 909–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenberg, I.; Seabra, F.P. Avoiding iris trauma from phacoemulsification in eyes with iridoschisis. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2004, 30, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanera, A.P.A.; Jorge, M.D. Pupil Management during Phacoemulsification in Patients with Iridoschisis. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2001, 26, 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.T.; Liu, C.S.C. Flexible iris hooks for phacoemulsification in patients with iridoschisis. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2000, 26, 1277–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, V.C.; Ghanem, E.A.; Ghanem, R.C. Iridectomy of the anterior iris stroma using the vitreocutter during phacoemulsification in patients with iridoschisis. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2003, 29, 2057–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).