The Third Month’s Development Predicts the Side and Oblique Sit and Walking

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Ethics Statement

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Quantitative Assessment in the Third Month of Life

2.2.2. The Qualitative Assessment at the Third Month of Life

2.2.3. Quantitative Assessment at the Age of 7–8 Months

2.2.4. Quantitative Assessment at the Age of 12 Months

3. Statistical Analysis

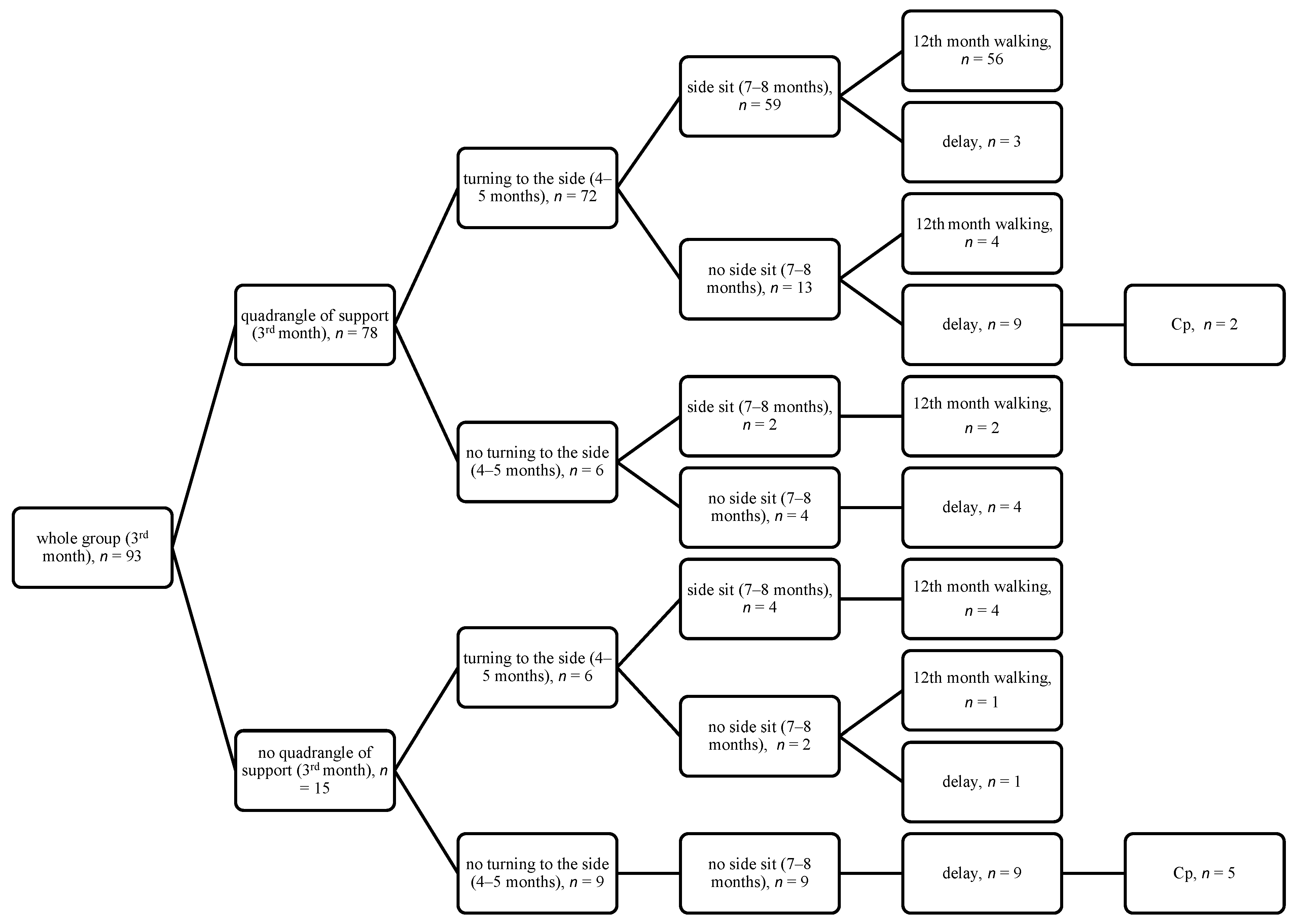

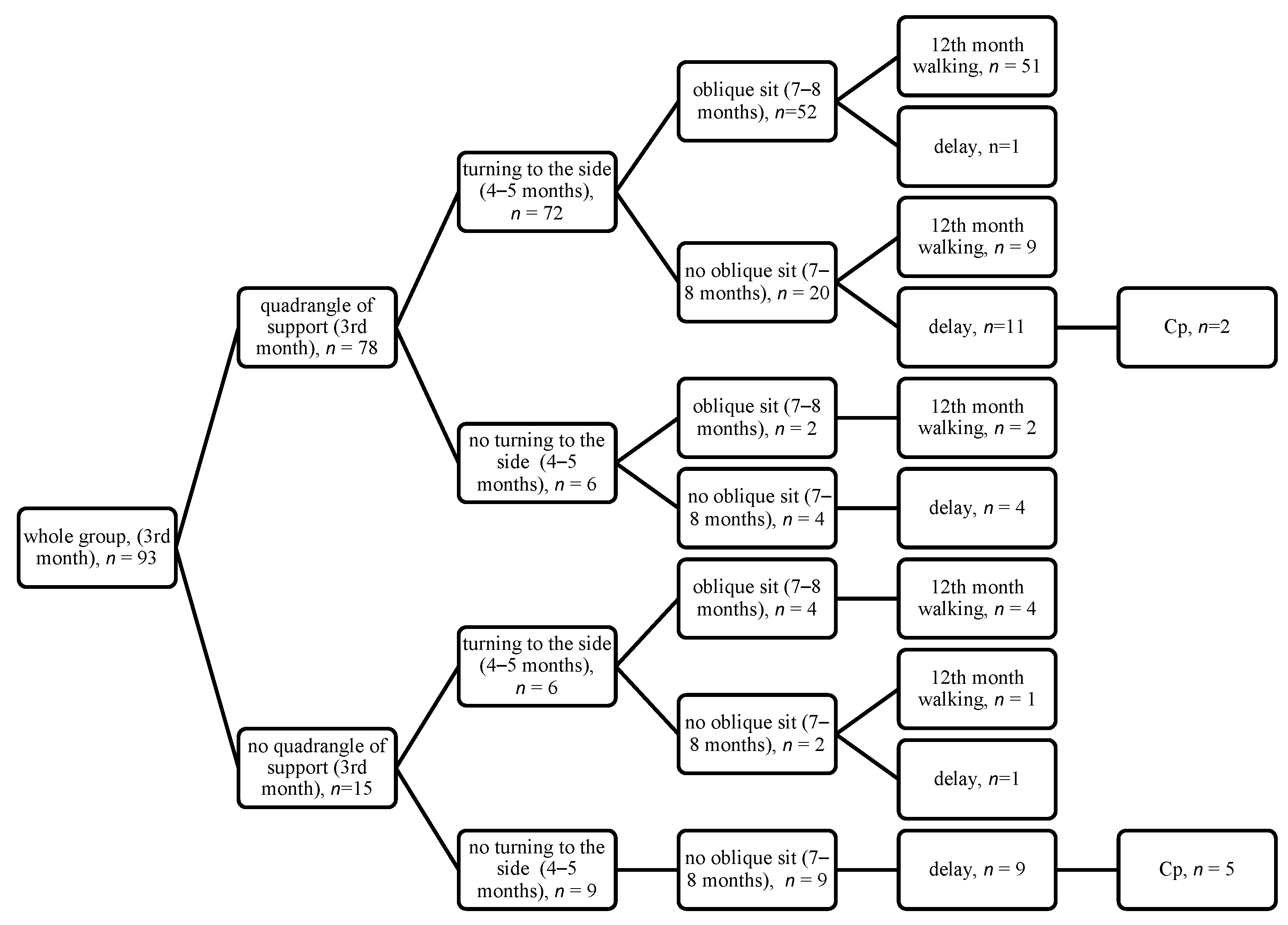

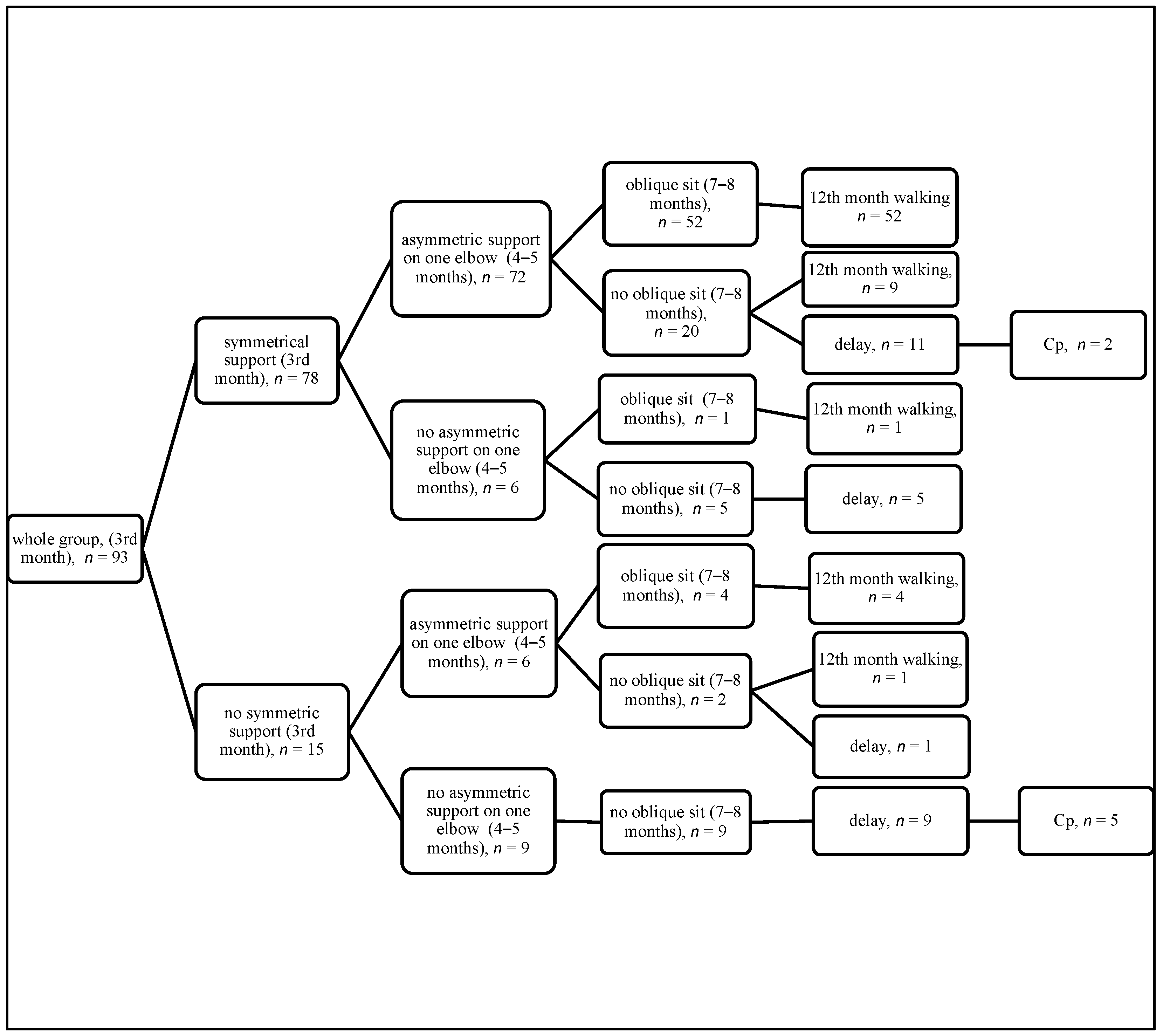

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bianco-Miotto, T.; Craig, J.M.; Gasser, Y.P.; Van Dijk, S.J.; Ozanne, S.E. Epigenetics and DOHaD: From basics to birth and beyond. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2017, 8, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltgen, A.C.; Valentini, N.C.; Marcelino, T.B.; Guimarães, L.S.P.; Da Silva, C.H.; Bernardi, J.R.; Goldani, M.Z. Different intrauterine environments and children motor development in the first 6 months of life: A prospective longitudinal cohort. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadders-Algra, M. Early human motor development: From variation to the ability to vary and adapt. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 90, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vojta, V.; Peters, A. The Vojta Principle; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewska, E.; Sobieska, M.; Moczko, J.; Kuklińska, A.; Laudańska-Krzemińska, I.; Osiński, W. Independent reaching of the sitting position depends on the motor performance in the 3rd month of life. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Novak, I.; Morgan, C.; Adde, L.; Blackman, J.; Boyd, R.N.; Brunstrom-Hernandez, J.; Cioni, G.; Damiano, D.; Darrah, J.; Eliasson, A.-C.; et al. Early, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, C.; Darrah, J.; Gordon, A.M.; Harbourne, R.; Spittle, A.; Johnson, R.; Fetters, L. Effectiveness of motor interventions in infants with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, C.; Romeo, D.M.; Chorna, O.; Novak, I.; Galea, C.; Del Secco, S.; Guzzetta, A. The Pooled Diagnostic Accuracy of Neuroimaging, General Movements, and Neurological Examination for Diagnosing Cerebral Palsy Early in High-Risk Infants: A Case Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcroft, C.; Dulson, P.; Dixon, J.; Embleton, N.; Basu, A.P. The predictive ability of the Lacey Assessment of Preterm Infants (LAPI), Cranial Ultrasound (cUS) and General Movements Assessment (GMA) for Cerebral Palsy (CP): A prospective, clinical, single center observational study. Early Hum. Dev. 2022, 170, 105589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soska, K.C.; Adolph, K.E. Postural position constrains multimodal object exploration in infants. Infancy 2014, 19, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piper, M.; Darrah, J. Motor Assessment of the Developing Infant Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS); Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eliks, M.; Sowińska, A.; Gajewska, E. The Polish Version of the Alberta Infant Motor Scale: Cultural Adaptation and Validation. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 949720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.J.; Wright, M.; Rosenbaum, P.; Avery, L.M. Gross motor function measure (GMFM-66 & GMFM-88) user’s manual. In Clinics in Developmental Medicine, 3rd ed.; Mac Keith Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewska, E.; Sobieska, M.; Samborski, W. Associations between Manual Abilities, Gross Motor Function, Epilepsy, and Mental Capacity in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Iran. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 8, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hadhud, M.; Gross, I.; Hurvitz, N.; Cahan, L.O.S.; Ergaz, Z.; Weiser, G.; Shlomai, N.O.; Friedman, S.E.; Hashavya, S. Serious Bacterial Infections in Preterm Infants: Should Their Age Be “Corrected”? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewska, E.; Moczko, J.; Naczk, M.; Naczk, A.; Sobieska, M. Impact of selected risk factors on motor performance in the third month of life and motor development in the ninth month. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flensborg-Madsen, T.; Mortensen, E.L. Predictors of motor developmental milestones during the first year of life. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2017, 176, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolph, K.E.; Hoch, J.E. The Importance of Motor Skills for Development. In Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop Series; Black, M.M., Singhal, A., Hillman, C.H., Eds.; S. Karger AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 95, pp. 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- de Lima-Alvarez, C.D.; Tudella, E.; van der Kamp, J.; Savelsbergh, G.J.P. Effects of postural manipulations on head movements from birth to 4 months of age. J. Mot. Behav. 2013, 45, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachwani, J.; Santamaria, V.; Saavedra, S.L.; Wood, S.; Porter, F.; Woollacott, M.H. Segmental trunk control acquisition and reaching in typically developing infants. Exp. Brain Research. Exp. Hirnforschung. Exp. Cereb. 2013, 228, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piper, M.C.; E Pinnell, L.; Darrah, J.; Maguire, T.; Byrne, P.J. Construction and validation of the Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS). Can. J. Public Health 1992, 83 (Suppl. S2), S46–S50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alhozyel, E.; Elbedour, L.; Balaum, R.; Meiri, G.; Michaelovski, A.; Dinstein, I.; Davidovitch, N.; Kerub, O.; Menashe, I. Association Between Early Developmental Milestones and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023, 51, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, A.A.; Kilgour, G.; Sandle, M.; Kidd, S.; Sheppard, A.; Swallow, S.; Stott, N.S.; Battin, M.; Korent, W.; Williams, S.A. Partnering Early to Provide for Infants At Risk of Cerebral Palsy (PĒPI ARC): Protocol for a feasibility study of a regional hub for early detection of cerebral palsy in Aotearoa New Zealand. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1344579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Whole group, n = 93 |

| Sex | boys, n = 50; girls, n = 43 |

| Born | at term, week 39 ± 1, n = 69; preterm, week 33 ± 3, n = 24 |

| Body mass | born at term 3470 ± 428/ preterm 2044 ± 730 |

| Delivery | Vaginally, n = 64; Cesarean section, n = 24; forceps, n = 4, vacuum, n = 2 |

| Apgar score at 5th minute | Good condition (8–10), n = 88; semi-severe condition (4–7), n = 4; severe condition (0–3), n = 1 |

| IVH | I°, n = 2; II°, n = 3; III°, n = 3; IV°, n = 1 |

| RDS | n = 9 |

| hypotrophy | n = 2 |

| hyperbilirubinemia | n = 2 |

| Elements of Quantitative Assessment | Side Sit OR and 95%CI; p > [z]  | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 | Oblique Sit OR and 95%CI  | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 | Final Assessment at 12 Months—Walking OR and 95%CI | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supine position 3rd month quadrangle of a support Prematurity Sex  | 20.2 (3.8–107.8); <0.001 0.3 (3.8–107.8); 0.102 1.0 (0.3–2.6); 0.923 | 13.43 0.0038 0.1180 | 9.1 (2.2–37.4); 0.002 0.5 (0.1–1.7); 0.281 1.0 (0.4–2.6); 0.921 | 11.47 0.0094 0.0939 | 31.8 (3.8–269.7); 0.001 0.9 (0.1–0.8); 0.032 0.8 (0.3–2.3); 0.711 | 19.74 0.0002 0.1791 |

| Supine position 4–5 months—turning to the side Prematurity Sex  | 29.2 (5.8–147.8); <0.001 0.7 (0.2–2.6); 0.582 1.2 (0.4–3.4); 0.799 | 26.09 <0.0001 0.2293 | 18.2 (3.7–88.4); <0.001 0.9 (0.3–2.8); 0.715 1.2 (0.4–1.2); 0.860 | 19.67 0.0002 0.16.11 | 46.5 (7.7–282.1); <0.001 0.3 (0.1–1.4); 0.127 1.0 (0.3–3.2); 0.972 | 31.13 <0.0001 0.2824 |

| Prone position 3rd month—symmetrical support on elbows Prematurity Sex  | 10.2 (2.7–38.1); 0.001 0.5 (0.1–1.7); 0.248 0.9 (0.3–2.5); 0.891 | 14.09 0.0028 0.1238 | 2.8 (0.9–8.9); 0.075 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.740 1.0 (1.4–2.5); 0.927 | 3.26 0.3537 0.0267 | 11.0 (2.7–45.1); 0.001 0.2 (0.1–1.1); 0.061 0.8 (0.3–2.3); 0.709 | 14.63 0.0022 0.1327 |

| Prone position 4–5 months—asymmetric support on one elbow Prematurity Sex  | 27.9 (5.6–138.2); <0.001 0.9 (0.3–3.2); 0.904 1.2 (0.4–3.5); 0.736 | 25.79 <0.0001 0.2266 | 18.0 (3.7–87.3); <0.001 1.1 (0.4–3.3); 0.866 1.2 (0.5–3.3); 0.665 | 19.67 0.0002 0.1610 | 36.3 (6.9–190.9); <0.001 0.4 (0.1–1.9); 0.271 1.1 (0.3–3.4); 0.898 | 29.62 <0.0001 0.2687 |

| Both 3rd month and 4–5 month features correct—supine position Prematurity Sex | 14.9 (4.2–52.2); <0.001 0.4 (0.1–1.7); 0.233 1.1 (0.4–3.3); 0.797 | 22.47 0.0001 0.1975 | 7.9 (2.5–24.8); <0.001 0.7 (0.2–2.1); 0.498 1.2 (0.5–3.0); 0.721 | 14.61 0.0022 0.1196 | 17.5 (4.4–68.5); <0.001 0.2 (0.4–1.0); 0.047 1.0 (0.3–3.0); 0.995 | 23.60 <0.0001 0.2141 |

| Both 3rd month and 4–5 month features correct—prone position Prematurity Sex | 14.8 (4.5–48.5); <0.001 0.6 (0.2–2.1); 0.390 1.1 (0.4–3.2); 0.845 | 24.41 <0.0001 0.2145 | 4.6 (1.6–12.8); 0.004 0.9 (0.3–2.5); 0.799 1.1 (0.4–2.8); 0.795 | 9.02 0.0290 0.0739 | 16.1 (4.6–56.1); <0.001 0.3 (0.1–1.2); 0.087 1.0 (0.3–2.9); 0.963 | 24.94 <0.0001 0.2263 |

| Elements of Qualitative Assessment— Supine Position | Side Sit OR and 95%CI; p > [z] | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 | Oblique Sit OR and 95%CI; p > [z] | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 | Final Assessment at 12 Months OR and 95%CI; p > [z] | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head symmetry Prematurity Sex | 5.8 (2.0–17.4); 0.002 0.6 (0.2–2.1); 0.471 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.931 | 10.63 0.0139 0.0935 | 4.8 (1.6–14.0); 0.004 0.8 (0.3–2.3); 0.693 1.0 (0.4–2.6); 0.934 | 8.80 0.0321 0.0721 | 3.2 (1.1–9.3); 0.038 0.4 (0.1–1.5); 0.204 0.9 (0.3–2.3); 0.792 | 5.20 0.1580 0.0471 |

| Shoulder in a balance between external and internal rotation—R Prematurity Sex | 8.4 (3.0–23.7); <0.001 0.6 (0.2–2.1); 0.458 1.2 (0.4–3.2); 0.770 | 17.94 0.0005 0.1577 | 5.8 (2.2–15.6); <0.001 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.706 1.2 (0.5–3.1); 0.683 | 13.46 0.0037 0.1102 | 5.2 (1.9–14.4); 0.002 0.4 (0.1–1.4); 0.165 1.0 (0.4–2.7); 0.988 | 11.40 0.0098 0.1034 |

| Shoulder in a balance between external and internal rotation—L Prematurity Sex | 13.2 (3.6–47.9); <0.001 0.5 (0.1–1.7); 0.250 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.888 | 18.91 0.0003 0.1662 | 5.2 (1.6–16.2); 0.005 0.8 (0.2–2.2); 0.607 1.0 (0.4–2.6); 0.943 | 8.74 0.0329 0.0716 | 14.6 (3.7–58.3); <0.001 0.2 (0.1–1.0); 0.056 0.8 (0.3–2.3); 0.698 | 19.56 0.0002 0.1775 |

| Wrist in an intermediate position—R Prematurity Sex | 8.9 (2.7–28.9); <0.001 0.5 (0.1–1.7); 0.270 0.9 (0.3–2.5); 0.859 | 15.05 0.0018 0.1323 | 5.03 (1.7–15.1); 0.004 0.7 (0.2–2.1); 0.552 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.970 | 9.01 0.0292 0.0737 | 9.9 (2.8–35.0); <0.001 0.2 (0.1–1.1); 0.062 0.8 (0.3–2.2); 0.661 | 16.06 0.0011 0.1457 |

| Wrist in an intermediate position—L Prematurity Sex | 25.3 (2.8–231.3); 0.004 0.6 (0.2–2.1); 0.430 1.0 (0.4–2.8); 0.946 | 13.43 0.0038 0.1180 | 16.2 (1.8–142.4); 0.012 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.691 1.1 (0.4–2.8); 0.833 | 10.08 0.0179 0.0826 | 44.2 (4.0–492.3); 0.002 0.3 (0.1–1.3); 0.096 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.883 | 17.41 0.0006 0.1580 |

| Palm in an intermediate position—R Prematurity Sex | 7.2 (1.3–40.4); 0.025 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.688 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.994 | 5.70 0.1270 0.0501 | 2.5 (0.5–12.0); 0.255 1.0 (0.4–2.7); 0.933 1.1 (0.4–2.5); 0.886 | 1.35 0.7184 0.0110 | 9.5 (1.6–56.7); 0.014 0.4 (0.1–1.6); 0.210 0.9 (0.3–2.4); 0.832 | 7.96 0.0469 0.0722 |

| Palm in an intermediate position—L Prematurity Sex | 25.3 (2.8–231.3); 0.004 0.6 (0.2–2.1); 0.430 1.0 (0.4–2.8); 0.946 | 13.43 0.0038 0.1180 | 16.2 (1.8–142.4); 0.012 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.691 1.1 (0.4–2.8); 0.833 | 10.08 0.0179 0.0826 | 44.2 (4.0–492.3); 0.002 0.3 (0.1–1.3); 0.096 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.883 | 17.41 0.0006 0.1580 |

| Thumb outside—R Prematurity Sex | 7.2 (1.3–40.4); 0.025 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.688 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.994 | 5.70 0.1270 0.0501 | 2.5 (0.5–12.0); 0.255 1.0 (0.4–2.7); 0.933 1.1 (0.4–2.5); 0.886 | 1.35 0.7184 0.0110 | 9.5 (1.6–56.7); 0.014 0.4 (0.1–1.6); 0.210 0.9 (0.3–2.4); 0.832 | 7.96 0.0469 0.0722 |

| Thumb outside—L Prematurity Sex | 25.3 (2.8–231.3); 0.004 0.6 (0.2–2.1); 0.430 1.0 (0.4–2.8); 0.946 | 13.43 0.0038 0.1180 | 16.2 (1.8–142.4); 0.012 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.691 1.1 (0.4–2.8); 0.833 | 10.08 0.0179 0.0826 | 44.2 (4.0–492.3); 0.002 0.3 (0.1–1.3); 0.096 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.883 | 17.41 0.0006 0.1580 |

| Spine in segmental extension Prematurity Sex | 7.2 (1.3–40.4); 0.025 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.688 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.994 | 5.70 0.1270 0.0501 | 2.5 (0.5–12.0); 0.255 1.0 (0.4–2.7); 0.933 1.1 (0.4–2.5); 0.886 | 1.35 0.7184 0.0110 | 9.5 (1.6–56.7); 0.014 0.4 (0.1–1.6); 0.210 0.9 (0.3–2.4); 0.832 | 7.96 0.0469 0.0722 |

| Pelvis extended Prematurity Sex | 18.0 (4.6–70.4); <0.001 0.3 (0.1–1.3); 0.117 0.9 (0.3–2.7); 0.913 | 23.56 <0.0001 0.2070 | 4.4 (1.5–13.0); 0.007 0.7 (0.2–2.1); 0.521 1.0 (0.4–2.6); 0.923 | 7.76 0.0512 0.0636 | 14.2 (3.6–56.0); <0.001 0.2 (0.0–0.9); 0.035 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.750 | 19.87 0.0002 0.1803 |

| Lower limb situated in moderate external rotation and lower limb bent at the right angle at hip and knee joints—R Prematurity Sex | 13.2 (2.3–75.9); 0.004 0.6 (0.2–1.9); 0.355 0.9 (0.4–2.5); 0.901 | 10.70 0.0135 0.0940 | 8.2 (1.5–44.4); 0.015 0.8 (0.2.–2.0); 0.614 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.959 | 7.38 0.0608 0.0604 | 24.1 (3.3–175.6); 0.002 0.2 (0.0–1.2); 0.075 0.8 (0.3–2.3); 0.726 | 14.96 0.0018 0.1358 |

| Lower limb situated in moderate external rotation and lower limb bent at the right angle at hip and knee joints—L Prematurity Sex | 13.5 (2.6–70.7); 0.002 0.7 (02–2.3); 0.586 1.0 (0.4–2.8); 0.932 | 12.46 0.0060 0.1095 | 4.9 (1.2–20.8); 0.030 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.910 1.1 (0.4–2.7); 0.840 | 5.26 0.1540 0.0430 | 19.1 (3.3–110.7); 0.001 0.4 (0.1–1.4); 0.151 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.902 | 15.80 0.0012 0.1434 |

| Foot in an intermediate position—R Prematurity Sex | 8.1 (1.9–34.2); 0.005 0.5 (0.1–1.8); 0.300 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.935 | 9.15 0.0274 0.0804 | 4.8 (1.2–18.9); 0.025 0.7 (0.2–2.2); 0.573 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.927 | 5.54 0.1362 0.0454 | 15.3 (2.8–85.1); 0.002 0.2 90.0–1.0); 0.057 0.8 (0.3–2.3); 0.751 | 13.91 0.0030 0.1262 |

| Foot in an intermediate position—L Prematurity Sex | 9.1 (1.9–44.0); 0.006 0.6 (0.2–1.9); 0.352 1.1 (0.4–2.9); 0.843 | 8.75 0.0329 0.0769 | 3.2 (0.8–13.2); 0.106 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.766 1.1 (0.5–2.7); 0.800 | 2.73 0.4351 0.0224 | 16.7 (2.7–103.9); 0.003 0.2 (0.0–1.1); 0.074 1.0 (0.4–2.7); 0.991 | 12.99 0.0047 0.1178 |

| Elements of Qualitative Assessment— Prone Position | Side Sit OR and 95%CI; p > [z] | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 | Oblique Sit OR and 95%CI; p > [z] | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 | Final Assessment at 12 Months OR and 95%CI; p > [z] | LR chi2 (3) Prob > chi2 Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated head rotation Prematurity Sex | 5.8 (2.1–16.2); 0.001 0.6 (0.2–1.9); 0.378 1.0 (0.4–2.8); 0.938 | 12.09 0.0071 0.1063 | 7.0 (2.5–19.8); <0.001 0.6 (0.2–2.0); 0.461 1.1 (0.4–3.0); 0.789 | 15.38 0.0015 0.1260 | 4.8 (1.7–13.7); 0.003 0.4 (0.1–1.3); 0.121 0.9 (0.3–2.5); 0.858 | 10.03 0.0183 0.0910 |

| Arm in front—R Prematurity Sex | 8.4 (2.7–25.6); <0.001 0.6 (0.2–2.0); 0.380 1.2 (0.4–3.2); 0.743 | 15.51 0.0014 0.1363 | 3.6 (1.3–10.1); 0.013 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.750 1.2 (0.5–2.9); 0.728 | 6.40 0.0937 0.0524 | 8.9 (2.8–28.8); <0.001 0.3 (0.1–1.2); 0.094 1.0 (0.4–3.0); 0.921 | 16.22 0.0010 0.1472 |

| Arm in front—L Prematurity Sex | 5.2 (1.8–14.6); 0.002 0.7 (0.2–2.1); 0.484 1.0 (0.4–2.6); 0.981 | 10.08 0.0179 0.0886 | 3.1 (1.2–8.4); 0.024 0.9 (0.3–2.4); 0.791 1.1 (0.4–2.6); 0.888 | 5.2 0.1565 0.0427 | 4.0 (1.4–11.5); 0.010 0.4 (0.1–1.4); 0.169 0.9 (0.3–2.3); 0.808 | 7.71 0.0525 0.0699 |

| Palm loosely open—R Prematurity Sex | 23.5 (2.6–207.5); 0.005 0.8 (0.2–2.6); 0.722 1.3 (0.5–3.4); 0.640 | 13.15 0.0043 0.1156 | 16.11 (1.8–140.2); 0.012 1.0 (0.3–2.8); 0.969 1.3 (0.5–3.2); 0.589 | 10.15 0.0174 0.0831 | 31.5 (3.3–297.4); 0.003 0.4 (0.1–1.6); 0.210 1.2 (0.4–3.2); 0.772 | 15.93 0.0012 0.1445 |

| Palm loosely open—L Prematurity Sex | 7.0 (1.2–39.3); 0.026 0.9 (03–2.8); 0.911 1.1 (0.4–2.9); 0.797 | 5.63 0.1312 0.0495 | 2.5 (0.5–12.2); 0.244 1.1 (0.0.4–2.9); 0.886 1.1 (0.5–2.7); 0.790 | 1.40 0.7047 0.0115 | 8.2 (1.4–46.8); 0.018 0.6 (0.2–1.8); 0.342 1.0 (0.4–2.7); 0.943 | 7.26 0.0640 0.0659 |

| Thumb outside—R Prematurity Sex | 25.3 (2.8–231.3); 0.004 0.6 (0.2–2.1); 0.430 1.0 (0.4–2.8); 0.946 | 13.43 0.0038 0.1180 | 16.2 (1.8–142.4); 0.012 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.691 1.1 (0.4–2.8); 0.833 | 10.08 0.0179 0.0826 | 44.2 (4.0–492.3); 0.002 0.3 (0.1–1.3); 0.096 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.883 | 17.41 0.0006 0.1580 |

| Thumb outside—L Prematurity Sex | 7.2 (1.3–40.4); 0.025 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.688 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.994 | 5.70 0.1270 0.0501 | 2.5 (0.5–12.2); 0.244 1.1 (0.0.4–2.9); 0.886 1.1 (0.5–2.7); 0.790 | 1.35 0.7184 0.0110 | 9.5 (1.6–56.7); 0.014 0.5 (0.1–1.6); 0.210 0.9 (0.3–2.4); 0.832 | 7.96 0.0469 0.0722 |

| Spine in segmental extension Prematurity Sex | 5.9 (2.2–16.1); 0.001 0.6 (0.2–2.0); 0.427 1.0 (0.4–2.8); 0.909 | 12.86 0.0050 0.1130 | 5.2 (2.0–13.9); 0.001 0.8 (0.2–2.2); 0.610 1.1 (0.4–2.9); 0.791 | 12.05 0.0072 0.0987 | 3.8 (1.4–10.3); 0.009 0.4 (0.1–1.4); 0.166 0.9 (0.4–2.5); 0.900 | 7.82 0.0498 0.0710 |

| Scapula situated in the medial position—R Prematurity Sex | 5.1 (1.7–15.4); 0.004 0.7 (0.2–2.1); 0.506 1.1 (0.4–2.9); 0.847 | 8.72 0.0332 0.0767 | 3.2 (1.1–9.2); 0.033 0.8 (0.3–2.5); 0.802 1.1 (0.5–2.8); 0.776 | 4.71 0.1941 0.0386 | 5.1 (1.6–15.8); 0.005 0.4 (0.1–1.4); 0.151 1.0 (0.4–2.6); 0.983 | 9.00 0.0293 0.0816 |

| Scapula situated in the medial position—L Prematurity Sex | 3.3 (1.2–9.1); 0.021 0.8 (0.3–2.40; 0.676 1.0 (0.4–2.6); 0.935 | 5.34 0.1488 0.0469 | 2.7 (1.0–7.3); 0.048 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.907 1.1 (0.4–2.7); 0.827 | 3.98 0.2633 0.0326 | 2.4 (0.9–6.8); 0.094 0.5 (0.2–1.6); 0.261 0.9 (0.4–2.4); 0.884 | 3.64 0.3029 0.0330 |

| Pelvis in an intermediate position Prematurity Sex | 13.3 (3.8–46.2); <0.001 0.4 (0.1–1.5); 0.160 0.9 (0.3–2.5); 0.809 | 20.86 0.0001 0.1833 | 5.0 (1.7–14.5); 0.003 0.7 (02–2.1); 0.498 1.0 (0.4–2.50); 0.993 | 9.35 0.0250 0.0766 | 10.7 (3.1–37.6); <0.001 0.2 (0.1–1.0); 0.047 0.8 (0.3–2.2); 0.662 | 17.54 0.0005 0.1592 |

| Lower limbs situated loosely—R Prematurity Sex | 14.7 (2.9–73.8); 0.001 0.4 (0.1–1.6); 0.204 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.920 | 13.91 0.0030 0.1222 | 8.1 (1.8–36.1); 0.006 0.6 (0.2–2.0); 0.437 1.0 (0.4–2.6); 0.938 | 9.19 0.0268 0.0753 | 40.6 (4.3–381.4); 0.001 0.1 (0.0–1.0); 0.044 0.8 (0.3–2.3); 0.729 | 20.25 0.0002 0.1838 |

| Lower limbs situated loosely—L Prematurity Sex | 8.3 (2.1–31.8); 0.002 0.6 (0.2–2.1); 0.447 1.0 (0.4–2.8); 0.929 | 10.70 0.0135 0.0940 | 3.4 (1.0–11.9); 0.050 0.9 (0.3–2.5); 0.816 1.1 (0.4–2.6); 0.839 | 4.02 0.2589 0.0330 | 12.6 (2.9–55.6); 0.001 0.3 (0.1–1.3); 0.098 0.9 (0.3–2.6); 0.893 | 14.70 0.0021 0.1334 |

| Foot in an intermediate position—R Prematurity Sex | 7.9 (1.3–46.7); 0.023 0.7 (0.2–2.1); 0.512 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.954 | 5.98 0.1124 0.0526 | 5.2 (0.9–29.6); 0.064 0.9 (0.3–2.4); 0.778 1.0 (0.4–2.5); 0.919 | 3.92 0.2707 0.0321 | 12.2 (1.8–82.2); 0.010 0.4 (0.1–1.4); 0.129 0.9 (0.3–2.3); 0.794 | 8.91 0.0306 0.0808 |

| Foot in an intermediate position—L Prematurity Sex | 7.3 (1.3–41.2); 0.025 0.8 (0.3–2.4); 0.718 1.1 (0.4–2.8); 0.832 | 5.75 0.1245 0.0505 | 2.5 (0.5–12.3); 0.248 1.0 (0.4–2.7); 0.978 1.1 (0.5–2.7); 0.808 | 1.38 0.7093 0.0113 | 9.5 (1.6–56.9); 0.014 0.5 (0.1–1.6); 0.225 1.0 (0.4–2.7); 0.970 | 7.96 0.0469 0.0722 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gajewska, E.; Surowińska, J.; Michalak, M.; Gajewski, J.; Chałupka, A.; Naczk, M.; Naczk, A.; Sobieska, M. The Third Month’s Development Predicts the Side and Oblique Sit and Walking. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8492. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238492

Gajewska E, Surowińska J, Michalak M, Gajewski J, Chałupka A, Naczk M, Naczk A, Sobieska M. The Third Month’s Development Predicts the Side and Oblique Sit and Walking. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8492. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238492

Chicago/Turabian StyleGajewska, Ewa, Joanna Surowińska, Michał Michalak, Jędrzej Gajewski, Anna Chałupka, Mariusz Naczk, Alicja Naczk, and Magdalena Sobieska. 2025. "The Third Month’s Development Predicts the Side and Oblique Sit and Walking" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8492. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238492

APA StyleGajewska, E., Surowińska, J., Michalak, M., Gajewski, J., Chałupka, A., Naczk, M., Naczk, A., & Sobieska, M. (2025). The Third Month’s Development Predicts the Side and Oblique Sit and Walking. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8492. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238492