Physiology and Molecular Mechanisms of the “Third Fluid Space”

Abstract

1. Crystalloid Fluid in Intensive Care

2. Distribution of Infused Fluid

3. History of the “Third Fluid Space”

4. Guyton’s Studies of Pif

5. Wiig’s Microneedles

6. Biomechanics of the Interstitial Space

7. Two Patterns for Pif and Volume Changes

7.1. Hydrostatic Mechanism: Elevated Capillary Hydrostatic Pressure Pushes Fluid from the Vascular Compartment into the Interstitial Space (Monophasic Pressure Change)

7.2. Inflammatory Mechanism: Acute Negative Interstitial Pressure Pulls Fluid into Interstitial Space; Increasing Volume Causes a Rise in Pif (Biphasic Pressure Change)

8. Pharmacological and Physiological Modulation of Pif

9. What the Physiology Tells the Clinician

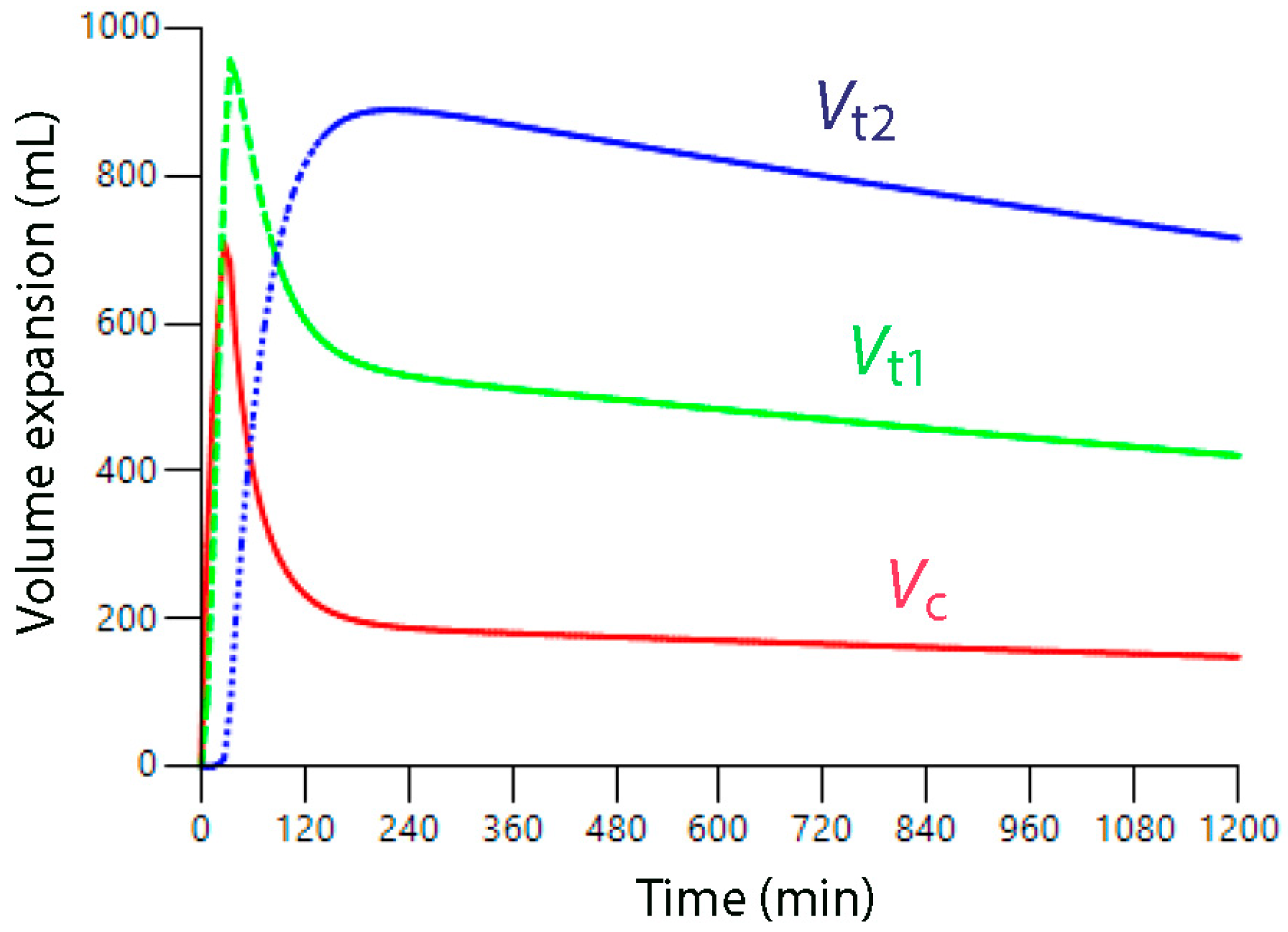

10. What Volume Kinetics Adds

11. Questioning the Role of the Glycocalyx

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arushi Bhattacharjee, S.; Kumar, A.; Khanna, P.; Chumber, S.; Kashyap, L.; Maitra, S. Association between cumulative fluid balance to estimated colloid oncotic pressure ratio and postoperative outcome in surgical patients requiring intensive management. Surgery 2025, 185, 109525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; de Louw, E.; Niemi, M.; Nelson, R.; Mark, R.G.; Celi, L.A.; Mukamal, K.J.; Danziger, J. Association between fluid balance and survival in critically ill patients. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 277, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, A.; Vincent, J.L. A positive fluid balance is an independent prognostic factor in patients with sepsis. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Marik, P.; Witters, I.; Cordemans, C.; Kirkpatrick, A.W.; Roberts, D.; Regenmortel, N. Fluid overload, de-resuscitation, and outcomes in critically ill or injured patients: A systematic review with suggestions for clinical practice. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2014, 46, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbrain, M.L.; Van Regenmortel, N.; Owczuk, R. It is time to consider the four D’s of fluid management. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2015, 47, s1–s5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Van Regenmortel, N.; Saugel, B.; De Tavernier, B.; Van Gaal, P.J.; Joannes-Boyau, O.; Teboul, J.L.; Rice, T.W.; Mythen, M.; Monnet, X. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: It is time to consider the four D’s and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann. Intensive Care 2018, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R.G. Volume kinetic analysis in living humans; background history and answers to 15 questions in physiology and medicine. Fluids 2025, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.G. Capillary filtration of plasma is accelerated during general anesthesia: A secondary volume kinetic analysis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 65, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, R.A.; Power, G.G. Effects of hypotonic, isotonic and hypertonic fluids on thoracic duct lymph flow. Am. J. Physiol. 1983, 245, R785–R791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shires, T.; Williams, J.; Brown, F. Acute changes in extracellular fluids associated with major surgical procedures. Ann. Surg. 1961, 154, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shires, T.; Brown, F.T.; Conizaro, P.C.; Summerville, N. Distributional changes in the extracellular fluid during acute hemorrhagic shock. Surg. Forum 1960, 11, 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R.G.; Dull, R.O. A slow-exchange interstitial fluid compartment in volunteers and anesthetized patients; kinetic analysis and physiological background. Anesth. Analg. 2024, 139, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.G. Sequential recruitment of body fluid spaces for increasing volumes of crystalloid fluid. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1439035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benias, P.C.; Wells, R.G.; Sackey-Aboagye, B.; Klavan, H.; Reidy, J.; Buonocore, D.; Miranda, M.; Kornacki, S.; Wayne, M.; Carr-Locke, D.L.; et al. Structure and distribution of an unrecognized interstitium in human tissues. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenaj, O.; Allison, D.H.R.; Imam, R.; Zeck, B.; Drohan, L.M.; Chiriboga, L.; Llewellyn, J.; Liu, C.Z.; Park, Y.N.; Wells, R.G.; et al. Evidence for continuity of interstitial spaces across tissue and organ boundaries in humans. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dull, R.O.; Hahn, R.G.; Dull, G.E. Anesthesia-induced lymphatic dysfunction. Anesthesiology 2024, 141, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondareff, W. Submicroscopic morphology of connective tissue ground substance with particular regard to fibrillogenesis and aging. Gerontologia 1957, 1, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haljamäe, H. Anatomy of the interstitial tissue. Lymphology 1978, 11, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guyton, A.C. A concept of negative interstitial pressure based on pressures in implanted perforated capsules. Circ. Res. 1963, 12, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyton, A.C.; Scheel, K.; Murphree, D. Interstitial fluid pressure III: Its effect on resistance to tissue fluid mobility. Circ. Res. 1966, 19, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.L.; Dumargne, H.; Hahn, R.G.; Hammed, A.; Lac, R.; Guilpin, A.; Slek, C.; Gerome, M.; Allaouchiche, B.; Louzier, V.; et al. Volume kinetics in a translational porcine model of stabilized sepsis with fluid accumulation. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, A.C.; Granger, H.J.; Taylor, A.E. Interstitial fluid pressure. Physiol. Rev. 1971, 51, 527–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, R.A.; Guyton, A.C.; Taylor, A.E. Reevaluation of the needle method for measuring interstitial fluid pressure. Am. J. Physiol. 1975, 229, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyton, A.C. Interstitial fluid pressure II. Pressure volume curves of the interstitial space. Circ. Res. 1965, 16, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, H.; Reed, R.; Aukland, K. Micropuncture measurements of interstitial fluid pressure in the rat subcutis and skeletal muscle: Comparison to wick-in-needle technique. Microvasc. Res. 1981, 21, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiig, H.; Reed, R.K.; Aukland, K. Measurement of interstitial fluid pressure in dogs; evaluation of methods. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1987, 253, H283–H290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, H.; Reed, R.K. Volume-pressure relationship (compliance) of interstitium in dog skin and muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1987, 253, H291–H298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, R.K.; Rubin, K. Transcapillary exchange: Role and importance of the interstitial fluid pressure and the extracellular matrix. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T.; Wiig, H.; Reed, R.K. Acute post burn edema: Role of strongly negative interstitial fluid pressure. Am. J. Physiol. 1988, 255, H1069–H1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T.; Onarheim, H.; Wiig, H.; Reed, R.K. Mechanisms behind increased dermal imbibition pressure in acute burn edema. Am. J. Physiol. 1989, 256, H940–H948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, D.; Passi, A.; de Luca, G.; Miserochi, G. Proteoglycan involvement during the development of lesional pulmonary edema. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 274, L203–L211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, D.; Passi, A.; Moriondo, A. The role of proteoglycans pulmonary edema development. Intensive Care Med. 2008, 34, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, A.; Berg, A.; Nedrebo, T.; Reed, R.K.; Rubin, K. Platelet-derived growth factor BB-mediated normalization of dermal interstitial fluid pressure after mast cell degranulation depends on b3 but not b1 integrins. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedrebo, T.; Karlsen, T.V.; Salvesen, G.S.; Reed, R.K. A novel function of insulin in rat dermis. J. Physiol. 2004, 59, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.; Ekwall, A.K.; Rubin, K.; Stjernschantz, J.; Reed, R.K. Effect of PGE1, PGI2 and PGF2a analogs on collagen gel compaction in vitro and interstitial pressure in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 1988, 274, H663–H671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodt, S.A.; Reed, R.K.; Ljungstrom, M.; Gustafasson, T.O.; Rubin, K. The anti-inflammatory agent a-trinositol exerts its edema-preventing effects through modulation of beta1 integrin function. Circ. Res. 1994, 75, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; McDermott, B.J. D-myo inositol 1,2,6, triphosphate (alpha-trinositol, pp56): Selective antagonist at neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y-receptor or selective inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol cell signaling? Gen. Pharm. 1998, 31, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlen, K.; Berg, A.; Stiger, F.; Tengholm, A.; Siegbahn, A.; Gylfe, E.; Reed, R.K.; Rubin, K. Cell interactions with collagen matrices In Vivo and In Vitro depend on phosphatidyl 3-kinase and free cytoplasmic calcium. Cell Adhes. Commun. 1998, 5, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuchel, R.; Berg, A.; Tallquist, M.; Ahlén, K.; Reed, R.K.; Rubin, K.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; Heldin, C.H.; Soriano, P. Platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor regulates interstitial fluid homeostasis through phosphotidyinositol-3′kinase signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 11410–11415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedrebo, T.; Reed, R.K.; Berg, A. Effect of a-trinositol on interstitial fluid pressure, edema generation and albumin extravasation after ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat hindlimb. Shock 2003, 20, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, U.N. Can glucose-insulin-potassium regimen suppress inflammatory bowel disease? Med. Hypothesis 2001, 57, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.F.; Kahn, C.R. The insulin signaling system. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilherme, A.; Czech, M.P. Stimulation of IRS-1-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt/protein kinase B but not glucose transport by beta-1-integrin signaling in rat adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 33119–33122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, O.S.; Liden, A.; Nedrebo, T.; Rubin, K.; Reed, R.K. Integrin avb3 acts downstream of insulin in normalization of interstitial fluid pressure in sepsis and in cell-mediated collagen gel contraction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 295, H555–H560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artursson, G.; Mellander, S. Acute changes in capillary filtration and diffusion in experimental burn injury. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1964, 62, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dull, R.O.; Hahn, R.G. Hypovolemia with peripheral edema: What is wrong? Crit. Care 2003, 27, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R.G. Accelerated lymph flow from infusion of crystalloid fluid during general anesthesia. BMC Anesth. 2024, 24, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkinson, B.R.; Border, J.R.; Heyden, W.C.; Schenk, W.G. Interstitial fluid pressure changes during hemorrhage with and without hypotension. Surgery 1963, 64, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McHale, N.G.; Roddie, I.C. The effect of intravenous adrenaline and noradrenaline infusion of peripheral lymph flow in sheep. J. Physiol. 1983, 341, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeown, J.G.; McHale, N.G.; Thornbury, K.D. Effect of electrical stimulation of the sympathetic chain on peripheral lymph flow in the anaesthetized sheep. J. Physiol. 1987, 393, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.G.; Li, Y.; Dull, R.O. Vasoactive drugs and the distribution of crystalloid fluid during acute sepsis. J. Intens. Med. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukland, K.; Reed, R.K. Interstitial-lymphatic mechanisms in the control of extracellular fluid volume. Physiol. Rev. 1993, 73, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, A.C.; Hall, J.E. Textbook of Medical Physiology, 9th ed.; Philadelphia, W.B., Ed.; Saunders Company: Englewood, CO, USA, 1996; p. 195, 311. [Google Scholar]

- Prather, J.W.; Taylor, A.E.; Guyton, A.C. Effect of blood volume, mean circulatory pressure, and stress relaxation on cardiac output. Am. J. Physiol. 1969, 216, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.G.; Nennesmo, I.; Rajs, J.; Sundelin, B.; Wroblevski, R.; Zhang, W. Morphological and X-ray microanalytical changes in mammalian tissue after overhydration with irrigating fluids. Eur. Urol. 1996, 29, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R.G.; Olsson, J.; Sótonyi, P.; Rajs, J. Rupture of the myocardial histoskeleton and its relation to sudden death after infusion of glycine 1.5% in the mouse. APMIS 2000, 108, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinbaum, S.; Tarbell, J.M.; Damiano, E.R. The structure and function of the endothelial glycocalyx layer. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 9, 121–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerci, P.; Ergin, B.; Uz, Z.; Ince, Y.; Westphal, M.; Heger, M.; Ince, C. Glycocalyx degradation is independent of vascular barrier permeability increase in nontraumatic hemorrhagic shock in rats. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 129, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergin, B.; Guerci, P.; Uz, Z.; Westphal, M.; Ince, Y.; Hilty, M.; Ince, C. Hemodilution causes glycocalyx shedding without affecting vascular endothelial barrier permeability in rats. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2020, 5, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R.G.; Zdolsek, M.; Krizhanovskii, C.; Ntika, S.; Zdolsek, J. Elevated plasma concentrations of syndecan-1 do not correlate with the capillary leakage of 20% albumin. Anesth. Analg. 2021, 132, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Qi, B.; Peng, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y.; Sun, T.; Ning, F.; Hao, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, T. Heparan sulfate acts in synergy with tight junctions through STAT3 signaling to maintain the endothelial barrier and prevent lung injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 147, 113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannaway, M.; Yang, X.; Meegan, J.E.; Coleman, D.C.; Yuan, S.Y. Thrombin-cleaved syndecan-3/-4 ectodomain fragments mediate endothelial barrier dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dull, R.O.; Hahn, R.G. The glycocalyx as a permeability barrier; basic science and clinical evidence. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, S.S.; Drewes, R.C.; Hedrick, M.S. Control of blood volume following hypovolemic challenge in vertebrate: Transcapillary versus lymphatic mechanisms. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2021, 254, 110878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levick, J.R.; Michel, C.C. Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling Principle. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, R.H.; Lenz, J.F.; Zhang, X.; Adamson, G.N.; Weinbaum, S.; Curry, F.E. Oncotic pressures opposing filtration across non-fenestrated rat microvessels. J. Physiol. 2004, 557, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajimura, M.; Wiig, H.; Reed, K.; Michel, C.C. Interstitial fluid pressure surrounding rat mesenteric venules during changes in fluid filtration. Exp. Physiol. 2001, 86, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiig, H. Pathophysiology of tissue fluid accumulation in inflammation. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 2945–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yi, S.; Zhu, Y.; Hahn, R.G. Volume kinetics of Ringer’s lactate solution in acute inflammatory disease. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 121, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.G. Maldistribution of fluid in preeclampsia; a retrospective kinetic analysis. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2024, 57, 103963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R.G.; Dull, R.O. Interstitial washdown and vascular albumin refill during fluid infusion: Novel kinetic analysis from three clinical trials. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2021, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dull, R.O.; Hahn, R.G. Physiology and Molecular Mechanisms of the “Third Fluid Space”. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8491. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238491

Dull RO, Hahn RG. Physiology and Molecular Mechanisms of the “Third Fluid Space”. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8491. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238491

Chicago/Turabian StyleDull, Randal O., and Robert G. Hahn. 2025. "Physiology and Molecular Mechanisms of the “Third Fluid Space”" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8491. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238491

APA StyleDull, R. O., & Hahn, R. G. (2025). Physiology and Molecular Mechanisms of the “Third Fluid Space”. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8491. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238491