Thoracoscopy-Guided vs. Ultrasound-Guided Paravertebral Block in Thoracoscopic Surgery: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Randomization and Blinding

2.4. Interventions

2.5. Anesthesia Protocol and Surgical Procedure

2.6. Postoperative Analgesia Protocol

2.7. Outcomes

2.8. Sample Size Calculation

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

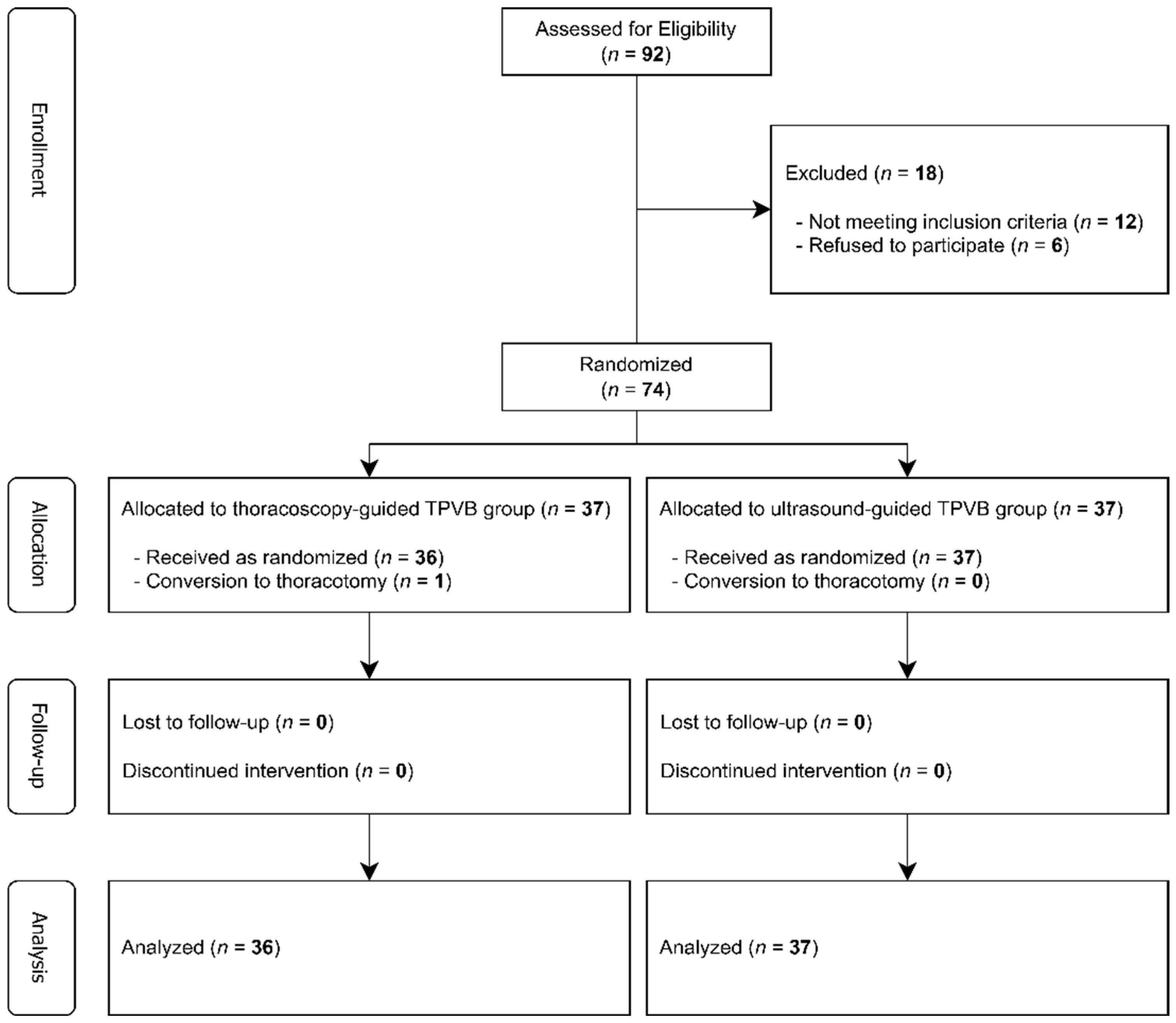

3.1. Participant Flow

3.2. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.3. Surgical and Anesthetic Characteristics

3.4. Pain Outcomes

3.5. Block Procedure Characteristics and Complications

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Batchelor, T.J.P.; Rasburn, N.J.; Abdelnour-Berchtold, E.; Brunelli, A.; Cerfolio, R.J.; Gonzalez, M.; Ljungqvist, O.; Petersen, R.H.; Popescu, W.M.; Slinger, P.D.; et al. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: Recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 55, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbershagen, H.J.; Aduckathil, S.; van Wijck, A.J.; Peelen, L.M.; Kalkman, C.J.; Meissner, W. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: A prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology 2013, 118, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Jen, T.T.H.; Hamilton, D.L. Regional analgesia for acute pain relief after open thoracotomy and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. BJA Educ. 2023, 23, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ercole, F.; Arora, H.; Kumar, P.A. Paravertebral Block for Thoracic Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2018, 32, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkad, B.; Heinke, T.L.; Sheriffdeen, R.; Khatib, D.; Brodt, J.L.; Meng, M.L.; Grant, M.C.; Kachulis, B.; Popescu, W.M.; Wu, C.L.; et al. Practice Advisory for Preoperative and Intraoperative Pain Management of Thoracic Surgical Patients: Part 1. Anesth. Analg. 2023, 137, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Ye, Z.; Wang, F.; Sun, G.F.; Ji, C. Comparative analysis of the analgesic effects of intercostal nerve block, ultrasound-guided paravertebral nerve block, and epidural block following single-port thoracoscopic lung surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 19, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, J.; You, J.; Chen, Y.; Song, C. Comparison of erector spinae plane block with paravertebral block for thoracoscopic surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 18, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaans, L.N.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.W.; Susa, D.; de Loos, E.R.; Mourisse, J.M.J.; Bouwman, R.A.; Verhagen, A.; van den Broek, F.J.C.; Meijer, P.; Kuut, M.; et al. Intercostal or Paravertebral Block vs Thoracic Epidural in Lung Surgery: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial. JAMA Surg. 2025, 160, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F.; Cao, X. The Impact of Different Regional Anesthesia Techniques on the Incidence of Chronic Post-surgical Pain in Patients Undergoing Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery: A Network Meta-analysis. Pain Ther. 2024, 13, 1335–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feray, S.; Lubach, J.; Joshi, G.P.; Bonnet, F.; Van de Velde, M. PROSPECT guidelines for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: A systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia 2022, 77, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Xu, X.; Tian, H.; He, J. Effect of Single-Injection Thoracic Paravertebral Block via the Intrathoracic Approach for Analgesia After Single-Port Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lung Wedge Resection: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Ther. 2021, 10, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Fang, S.; Wang, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhan, T.; Wu, M. Patient-Controlled Paravertebral Block for Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery: A Randomized Trial. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 106, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shu, L.; Lin, C.; Yang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Cui, X.; Lin, X.; et al. Comparison Between Intraoperative Two-Space Injection Thoracic Paravertebral Block and Wound Infiltration as a Component of Multimodal Analgesia for Postoperative Pain Management After Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lobectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2015, 29, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xie, Y.X.; Zhang, M.; Du, J.H.; He, J.X.; Hu, L.H. Comparison of Thoracoscopy-Guided Thoracic Paravertebral Block and Ultrasound-Guided Thoracic Paravertebral Block in Postoperative Analgesia of Thoracoscopic Lung Cancer Radical Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Ther. 2024, 13, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenesseau, J.; Fourdrain, A.; Pastene, B.; Charvet, A.; Rivory, A.; Baumstarck, K.; Bouabdallah, I.; Trousse, D.; Boulate, D.; Brioude, G.; et al. Effectiveness of Surgeon-Performed Paravertebral Block Analgesia for Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2023, 158, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.Z.; Wang, B.; Dai, T. The efficacy of thoracic paravertebral block for thoracoscopic surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2018, 97, e13771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y.; Niu, Z. Effects of ultrasound-guided paravertebral block on MMP-9 and postoperative pain in patients undergoing VATS lobectomy: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krediet, A.C.; Moayeri, N.; van Geffen, G.J.; Bruhn, J.; Renes, S.; Bigeleisen, P.E.; Groen, G.J. Different Approaches to Ultrasound-guided Thoracic Paravertebral Block: An Illustrated Review. Anesthesiology 2015, 123, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myles, P.S.; Myles, D.B.; Galagher, W.; Boyd, D.; Chew, C.; MacDonald, N.; Dennis, A. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: The minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017, 118, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naja, Z.M.; El-Rajab, M.; Al-Tannir, M.A.; Ziade, F.M.; Tayara, K.; Younes, F.; Lönnqvist, P.A. Thoracic paravertebral block: Influence of the number of injections. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2006, 31, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A. The ratio of confidence interval above the minimal clinically important difference. Anaesthesia, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wu, C.; Wu, C.; Yu, H.; Chen, C.; He, H.; Wu, M. Paravertebral vs Epidural Anesthesia for Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery: A Randomized Trial. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2023, 116, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.K.; Kang, M.K.; Woon, H.; Hwang, Y.H. The feasibility of thoracoscopic-guided intercostal nerve block during uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy of the lung. J. Minim. Access Surg. 2022, 18, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Ashken, T.; West, S.; Macfarlane, A.J.R.; El-Boghdadly, K.; Albrecht, E.; Chin, K.J.; Fox, B.; Gupta, A.; Haskins, S.; et al. Core outcome set for peripheral regional anesthesia research: A systematic review and Delphi study. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2022, 47, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogatzki-Zahn, E.M.; Liedgens, H.; Hummelshoj, L.; Meissner, W.; Weinmann, C.; Treede, R.D.; Vincent, K.; Zahn, P.; Kaiser, U. Developing consensus on core outcome domains for assessing effectiveness in perioperative pain management: Results of the PROMPT/IMI-PainCare Delphi Meeting. Pain 2021, 162, 2717–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazy, M.A.; Awad, G.; Abdellatif, A.; Saleh, M.E.; Sanad, M. Ultrasound versus thoracoscopic-guided paravertebral block during thoracotomy. Asian Cardiovasc. Thorac. Ann. 2021, 29, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, X.K.; Zhou, H.; Cong, Z.Z.; Wu, W.J.; Qiang, Y.; Shen, Y. Paravertebral block with modified catheter under surgeon’s direct vision after video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 4115–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiperm, C.; Tanavalee, C.; Kampitak, W.; Amarase, C.; Ngarmukos, S.; Tanavalee, A. Intraoperative Surgeon-Performed versus Conventional Anesthesiologist-Performed Continuous Adductor Canal Block in Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Knee Surg. 2024, 37, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawa, A.; El-Boghdadly, K. Regional anesthesia by nonanesthesiologists. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2018, 31, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, L.T.; Pekas, D.R.; Mahoney, W.A.; Stack Hankey, M.; Adrados, M.; Moskal, J.T. Intraoperative Surgeon-Administered Adductor Canal Block Is a Safe Alternative to Preoperative Anesthesiologist-Administered Adductor Canal Block in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2024, 39, S120–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.M.; Bharde, S.; Sikandar, S. The mechanisms and management of persistent postsurgical pain. Front. Pain Res. 2023, 4, 1154597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalanathan, K.; Knight, T.; Rasburn, N.; Joshi, N.; Molyneux, M. Early Versus Late Paravertebral Block for Analgesia in Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lung Resection. A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2019, 33, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledowski, T. Objective monitoring of nociception: A review of current commercial solutions. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, e312–e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| T-TPVB (n = 36) | U-TPVB (n = 37) | ASD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.8 ± 8.4 | 63.7 ± 7.9 | 0.135 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.3 ± 2.2 | 23.7 ± 1.9 | 0.195 |

| Male sex | 25 (69.4%) | 22 (59.5%) | 0.209 |

| Smoking history | 16 (44.4%) | 15 (40.5%) | |

| Hypertension | 10 (27.8%) | 13 (35.1%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (19.4%) | 6 (16.2%) | 0.079 |

| ASA classification | 0.159 | ||

| I–II | 23 (63.9%) | 25 (67.6%) | |

| III | 13 (36.1%) | 12 (32.4%) |

| T-TPVB (n = 36) | U-TPVB (n = 37) | ASD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery duration, min | 165.0 ± 11.2 | 170.6 ± 10.6 | 0.514 |

| Anesthesia duration, min | 191.4 ± 9.5 | 196.5 ± 10.9 | 0.499 |

| Laterality | 0.135 | ||

| Right | 22 (61.1%) | 25 (67.6%) | |

| Left | 14 (38.9%) | 12 (32.4%) | |

| Procedure | 0.018 | ||

| Lobectomy | 25 (69.4%) | 26 (70.3%) | |

| Segmentectomy | 11 (30.6%) | 11 (29.7%) | |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 125.6 ± 34.6 | 120.6 ± 34.0 | 0.146 |

| Utility incision length, cm | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 0.392 |

| Chest tube number | 0.102 | ||

| 1 | 32 (88.9%) | 34 (91.9%) | |

| ≥2 | 4 (11.1%) | 3 (8.1%) | |

| Chest tube duration | 0.112 | ||

| <24 h | 28 (77.8%) | 27 (73.0%) | |

| ≥24 h | 8 (22.2%) | 10 (27.0%) | |

| Remifentanil consumption, µg/kg/min | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.283 |

| T-TPVB (n = 36) | U-TPVB (n = 37) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 h | VAS-R | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.8) | 0.233 |

| VAS-D | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 0.2 (−0.4 to 0.8) | 0.514 | |

| Fentanyl, µg | 18.6 ± 5.9 | 16.9 ± 5.4 | 1.7 (−1.0 to 4.3) | 0.213 | |

| 1–6 h | VAS-R | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.7) | 0.284 |

| VAS-D | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.7) | 0.342 | |

| Fentanyl, µg | 17.9 ± 6.0 | 16.3 ± 5.8 | 1.5 (−1.2 to 4.3) | 0.271 | |

| 6–24 h | VAS-R | 3.6 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 0.9 | −0.0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | 0.877 |

| VAS-D | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.7) | 0.801 | |

| Fentanyl, µg | 27.6 ± 4.6 | 28.6 ± 6.9 | −1.0 (−3.7 to 1.8) | 0.484 | |

| 24–48 h | VAS-R | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.3) | 0.502 |

| VAS-D | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 0.5 (−0.1 to 1.2) | 0.124 | |

| Fentanyl, µg | 35.1 ± 5.9 | 34.3 ± 4.8 | 0.7 (−1.8 to 3.2) | 0.554 | |

| Cumulative fentanyl, µg | 99.1 ± 11.5 | 96.1 ± 13.2 | 3.0 (−2.8 to 8.8) | 0.310 |

| T-TPVB (n = 36) | U-TPVB (n = 37) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block failure | 2 (5.6%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0.981 |

| Procedural time, s | 280.9 ± 23.4 | 503.6 ± 26.4 | <0.001 |

| Dermatome spread, median [IQR] | 7 [6, 7] | 7 [6, 8] | 0.263 |

| Total spinal anesthesia | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.99 |

| Neurological complications | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.99 |

| Vascular injury | 2 (5.6%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0.981 |

| Pneumothorax | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.7%) | >0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, S.B.; Hyun, K.; Choi, H. Thoracoscopy-Guided vs. Ultrasound-Guided Paravertebral Block in Thoracoscopic Surgery: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8493. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238493

Hong SB, Hyun K, Choi H. Thoracoscopy-Guided vs. Ultrasound-Guided Paravertebral Block in Thoracoscopic Surgery: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8493. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238493

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Seok Beom, Kwanyong Hyun, and Hoon Choi. 2025. "Thoracoscopy-Guided vs. Ultrasound-Guided Paravertebral Block in Thoracoscopic Surgery: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Trial" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8493. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238493

APA StyleHong, S. B., Hyun, K., & Choi, H. (2025). Thoracoscopy-Guided vs. Ultrasound-Guided Paravertebral Block in Thoracoscopic Surgery: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8493. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238493