Abstract

Identification of predictors of long COVID-19 is essential for managing healthcare plans of patients. This systematic literature review and meta-analysis aimed to identify risk factors not associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, but rather potentially predictive of the development of long COVID-19. MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases, as well as medRxiv and bioRxiv preprint servers were screened through 15 September 2022. Peer-reviewed studies or preprints evaluating potential pre-SARS-CoV-2 infection risk factors for the development of long-lasting symptoms were included. The methodological quality was assessed using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPSs) tool. Random-effects meta-analyses with calculation of odds ratio (OR) were performed in those risk factors where a homogenous long COVID-19 definition was used. From 1978 studies identified, 37 peer-reviewed studies and one preprint were included. Eighteen articles evaluated age, sixteen articles evaluated sex, and twelve evaluated medical comorbidities as risk factors of long COVID-19. Overall, single studies reported that old age seems to be associated with long COVID-19 symptoms (n = 18); however, the meta-analysis did not reveal an association between old age and long COVID-19 (n = 3; OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.03, p = 0.17). Similarly, single studies revealed that female sex was associated with long COVID-19 symptoms (n = 16); which was confirmed in the meta-analysis (n = 7; OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.86, p = 0.01). Finally, medical comorbidities such as pulmonary disease (n = 4), diabetes (n = 1), obesity (n = 6), and organ transplantation (n = 1) were also identified as potential risk factors for long COVID-19. The risk of bias of most studies (71%, n = 27/38) was moderate or high. In conclusion, pooled evidence did not support an association between advancing age and long COVID-19 but supported that female sex is a risk factor for long COVID-19. Long COVID-19 was also associated with some previous medical comorbidities.

1. Introduction

Long COVID-19 is a term used for defining the persistence of signs and symptoms in people who recovered from an acute Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection [1]. Long COVID-19 is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as: “post-COVID-19 condition, occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset, with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis [2].” Several meta-analyses investigating the prevalence of post-COVID-19 symptoms have been published, concluding that around 30–50% of subjects who recover from a SARS-CoV-2 infection develop persistent symptoms lasting up to one year [3,4]. A recent meta-analysis concluded that two years after the initial spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), up to 42% of infected patients experienced long COVID-19 symptoms [5].

Different narrative reviews have mentioned prognostic aspects, but no comprehensive synthesis has been provided so far [6,7,8,9]. Identification of potential risk factors associated with post-COVID-19 syndrome is important since identifying individuals at higher risk can guide management healthcare plans for these patients and reorganize healthcare accordingly. Iqbal et al. tried to pool data, but these authors were only able to pool prevalence data of post-COVID-19 symptomatology, but not risk factors [10]. All these narrative reviews have suggested that female sex, old age, higher number of comorbidities, higher viral load, and greater number of COVID-19 onset symptoms can be potential risk factors for long COVID-19 [6,7,8,9,10]. However, no systematic search or assessment of methodological quality was conducted in these reviews [6,7,8,9,10]. Two meta-analyses have recently focused on risk factors of long COVID-19. Maglietta et al. identified that female sex was a risk factor for long COVID-19 symptoms, whereas a more severe condition at the acute phase was associated just with long COVID-19 respiratory symptoms [11]. Thompson et al. found that old age, female sex, white ethnicity, poor pre-pandemic health, obesity, and asthma can predict long COVID-19 symptoms [12]. However, this analysis included just studies from the United Kingdom, and used the definition of long COVID-19 proposed by the National Institute for Health Care and Excellence (NICE) [13].

Accordingly, current evidence on risk factors associated with post-COVID-19 condition is heterogeneous. Risk factors can be classified as pre-infection (e.g., age, sex, previous comorbidities, and previous health status) and infection-associated (e.g., disease severity, symptoms at onset, viral load, hospitalization stay, and intensive care unit admission) factors. The current systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to identify factors not directly associated with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (i.e., pre-infection factors) such as age, sex, and previous medical comorbidities, which may predict the development of long COVID-19 symptomatology.

2. Methods

This systematic literature review and meta-analysis aiming to identify the association of age, sex, and comorbidities as predictive factors for development of long COVID-19 was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement of 2020 [14]. We also followed specific criteria recommended by Riley et al. to systematic reviews and the meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies [15]. The review study was prospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) database (https://osf.io/79pdg).

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

Two different authors performed an electronic search for articles published up to 15 September 2022 MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases, as well as on preprint servers medRxiv and bioRxiv, using the following search terms: “long COVID-19” OR “post-acute COVID” OR “post-COVID-19 condition” OR “long hauler” AND “age” OR “sex” OR “medical comorbidities” OR “transplant” OR “obesity” OR “diabetes” OR “hypertension” OR “pulmonary disease” OR “asthma” OR “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease”. The search was focused on the medical comorbidities likely associated with a more severe COVID-19 condition. Combinations of these search terms using Boolean operators are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Database formulas during literature search.

The Population, Intervention, Comparison. and Outcome (PICO) principle was used to describe the inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Population: Adults (>18 years) infected by SARS-CoV-2 and diagnosed with real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay. Subjects could have been hospitalized or not by SARS-CoV-2 acute infection.

Intervention: Not applicable.

Comparison: People infected by SARS-CoV-2 who did not develop long COVID-19 symptoms.

Outcome: Collection of long COVID-19 symptoms developed after an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection by personal, telephone, or electronic interview. We defined post-COVID-19 condition according to Soriano et al. [2], where “post-COVID-19 condition occurs in individuals with positive history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from onset of COVID-19, with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by alternative diagnosis.” We considered any long COVID-19 symptom appearing after the infection, e.g., fatigue, dyspnea, pain, brain fog, memory loss, skin rashes, palpitations, cough, and sleep problems. Results should be reported as odds ratio (OR), hazards ratio (HR), or mean incidence of the symptoms.

2.2. Screening Process, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

This review included observational cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies whether presence of risk factors for development of symptoms appearing after an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection were investigated in COVID-19 survivors, either hospitalized or non-hospitalized. The current review was limited to human studies and English language papers. Editorials, opinion, and correspondence articles were excluded.

Two authors screened title and abstract of publications obtained from database search and removed duplicates. Full text of eligible articles was retrieved and analyzed. The following data were extracted from each study: authors, country, design, sample size, age range, assessment of symptoms, long COVID-19 symptoms, and effect (measure) of risk factor studied. Discrepancies between reviewers in any part of the screening and data extraction process were resolved by a third author.

2.3. Risk of Bias

The Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPSs) tool was used to determine the risk of bias (RoB) of the studies [16]. The QUIPS consists of six domains such as study participation, study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, adjustment for other prognostic factors, and statistical analysis. RoB was initially evaluated by two authors. If there is disagreement, a third researcher arbitrated a consensus decision. Risk of bias was scored as low, moderate, or high as follows: 1 if all domains are classified as having low RoB, or just one as moderate RoB, the paper was classified as low RoB (green); 2 if one or more domains are classified as having high RoB; or ≥3 if all domains have moderate RoB, the paper was classified as high RoB (red). All papers in between were classified as having moderate RoB (yellow) [17].

2.4. Data Synthesis

We conducted a qualitative synthesis of data for those risk factors where the heterogeneity of results did not permit to perform a meta-analysis. We only included articles in the meta-analysis that followed the Soriano et al. definition of post-COVID-19 condition [2], hence meta-analysis was possible for age and sex.

To synthesize the association between age and sex with post-COVID-19 condition, random-effects meta-analyses were performed using MetaXL software ( https://www.epigear.com/index_files/metaxl.html) to estimate weighted mean differences (for age) and pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for sex and age above 60 years (old adults). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Given the heterogeneity expected, a random-effects model was employed. Measures of heterogeneity such as the I square statistics and Cochran’s Q test statistic and p-value are also reported. When each age group was reported using median and interquartile range values, the method described by Wan was used for transformation in mean and standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

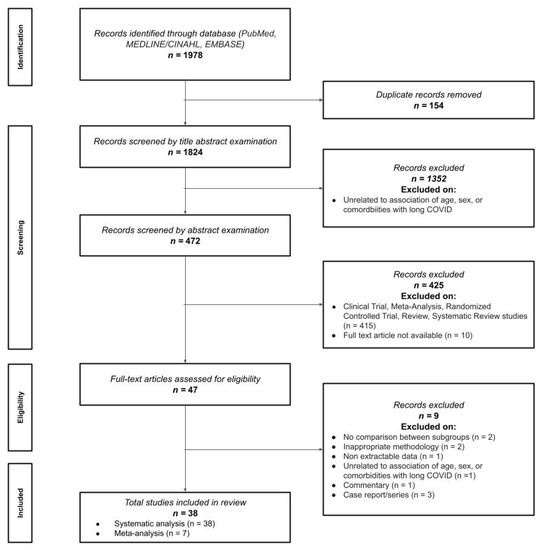

The electronic search allowed to initially identify 1978 titles for screening. After removing duplicates (n = 154) and papers not directly related to risk factors (n = 1352), 472 studies remained for abstract examination. Four hundred and twenty-five (n = 425) were excluded after reading the abstract, thus leading to a total of 47 text articles for eligibility (Figure 1). Nine articles were excluded because there were no comparisons between subgroups (n = 2) [18,19], inappropriate methodology (n = 2) [12,20], data not extractable (n = 1) [21], unrelated to association of risk factors (n = 1) [22], and type of literature commentary, case reports, and case series (n = 3) [23,24,25]. A total number of 37 peer-reviewed studies and one pre-print study were finally included [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. All papers could be included in qualitative analysis, whereas seven of these could also be pooled in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

3.2. Age and Post-COVID-19 Condition

A total of 18 articles, including 819,884 COVID-19 survivors analyzed age as a risk factor for developing long COVID-19 symptoms (Table 2) [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Four articles used percentages [27,33,34,38], five used means [26,31,40,41,43], seven OR [28,29,30,32,36,37,39], one adjusted OR (aOR) [35], and one adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) [42]. Eight articles included population samples aged ≥50 years old [27,28,32,35,37,38,40,41], eight individuals aged between 40 and 49 years [26,29,31,33,34,39,42,43], and one a population between 18 and 64 years [27]. Two studies included children aged 10–12 years [30,36], but data from these age groups were not considered in the main analyses.

Table 2.

Studies investigating the effect of age in long COVID-19 symptomatology [10,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

Overall, most articles observed that old age was associated with long COVID-19 symptoms [26,28,29,31,33,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,43]. Contrastingly, Peghin et al. did not find an association between age and long COVID-19 symptoms [32]. Subramanian et al. stated that adults aged >70 years displayed lower risk of developing long COVID-19 symptoms than those aged 30–39 years [42].

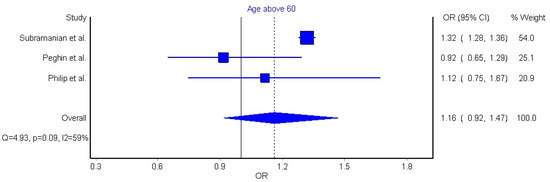

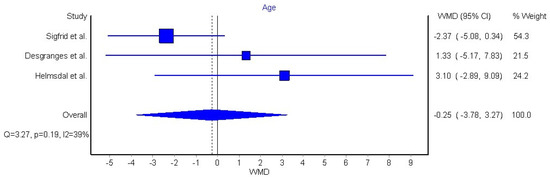

Three articles (n = 30,371 patients) were included in the meta-analysis based on their similar study design, study outcomes, and long COVID-19 definition [32,42,44]. We grouped individuals aged over 60 years old, since this age group is considered to be at higher risk of severe COVID-19. The meta-analysis did not reveal a significant association between old age and long COVID-19 symptomatology (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.03, Q = 3.54, p = 0.17, I2: 44%, Figure 2). Another three articles reporting data as mean (with their standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) were also pooled [42,45,46]. We pooled these data through a random effects model, resulting in a non-significant weighted mean difference (WMD) of −0.25 (95% CI −3.78 to 3.27, Q = 3.27, p = 0.19, I2: 39%, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Pooled analysis of odds ratio (OR) for the association between age older than 60 years and the presence of long COVID-19 symptoms [32,42,44].

Figure 3.

Pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) for the association between age as continuous variable and the presence of long COVID-19 symptoms [43,45,46].

3.3. Sex and Post-COVID-19 Condition

A total of 16 articles [32,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] including 504,044 COVID-19 survivors were used in the analysis of sex as a risk factor for developing long COVID-19 symptomatology (Table 3). Data were presented as OR, aOR, HR, aHR, and percentage. Seven articles used OR [32,47,48,49,50,51,52], two used aOR [45,53], another two used both OR and aOR [46,54], while three articles used percentage [43,44,55], one article used both percentage and OR [56], and one article used both HR and aHR [42].

Table 3.

Studies investigating the effect of sex in long COVID-19 symptomatology [32,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55].

Fourteen articles observed that female sex (n = 276,953) was associated with higher risk of long COVID-19 [32,42,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56], whilst two articles (n = 475) reported that female sex was not associated with higher risk of long COVID-19 [43,44].

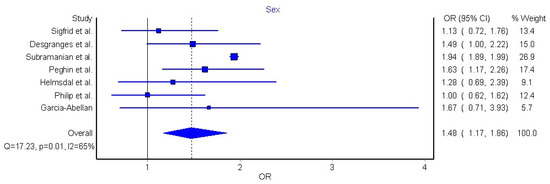

Seven articles (n = 386,234 COVID-19 patients who recovered from acute SARS-CoV-2 infection) were included in the meta-analysis due to their similarities in study design, definition of long COVID-19, as well as similarities in data presentation [32,42,43,44,45,46,50]. The meta-analysis revealed that female sex was significantly associated with nearly 50% higher risk (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.86, Q = 17.2, p = 0.01, I2: 65%, Figure 4) of long COVID-19 symptomatology.

Figure 4.

Pooled analysis of odds ratio (OR) for the association between sex and the presence of long COVID-19 [32,42,43,44,45,46,50].

3.4. Medical Comorbidities and Post-COVID-19 Condition

A total of 12 articles with 677,045 COVID-19 survivors were analyzed for association between long COVID-19 and comorbidities (Table 4) [29,39,44,52,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Four comorbidities were included: pulmonary disease (n = 4), diabetes (n = 1), obesity (n = 6), and organ transplantation (n = 1). Data were presented as means, medians, percentages, odds ratio (OR), and incident rate ratio (IRR). One study used mean [61], one used both median and percentage [59], three used percentage only [44], five used OR [29,39,52,55,60], and two used both OR and IRR [57,59].

Table 4.

Studies investigating the effect of previous medical comorbidities in long COVID-19 symptomatology [29,39,44,52,53,56,58,59,60,61,62,63].

Three articles on pulmonary disease revealed an association between asthma and longer symptom duration among patients recovering from COVID-19 [29,44,60]. However, both asthma and chronic pulmonary disease were not associated with long COVID-19 in one study [52]. For diabetes, no difference was found in the number of long COVID-19 symptoms among diabetic and non-diabetic patients [57]. For obesity, all six articles noted that this metabolic disease was associated with worse health due to increased number of long COVID-19 symptoms [39,59], longer persistence of symptoms [56,63], more presence of pathological pulmonary limitations [61], and metabolic abnormalities [58]. Meanwhile, one study on kidney transplant patients revealed that patients have higher susceptibility to developing long COVID-19 symptoms, although this did not affect mortality rate [62].

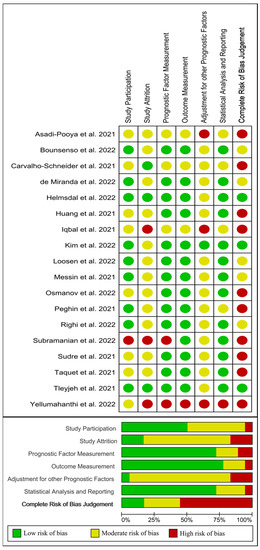

3.5. Risk of Bias

From out of 18 papers evaluating age as risk factor [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], three [35,41,43] were classified as low risk of bias (green), five [26,37,38,39,40] as moderate risk of bias (yellow), and the remaining ten [27,28,29,31,32,33,34,36,42,51] as high risk of bias (red). Figure 5 visually graphs that the most frequent risk of bias was adjustment for other prognostic factor (i.e., if important potential confounding factors were appropriately accounted for), which was properly performed in just one study [41].

Figure 5.

Plot of the risk of bias of those studies investigating age as a risk factor of long COVID-19 [10,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

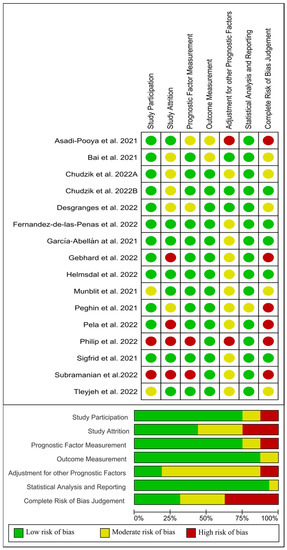

On the other hand, from 16 papers evaluating sex as a risk factor [32,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56], four studies [45,50,53,55] were classified as low risk of bias (green), five [46,49,52,54,56] as moderate risk of bias (yellow), and the remaining seven [32,42,43,44,47,48,51] as high risk of bias (red). Figure 6 visually graphs that the most frequent risk of bias in this group of studies were adjustment for other prognostic factors and study attrition (i.e., the representativeness of the participants with follow-up data with respect to those originally enrolled in the study, selection bias).

Figure 6.

Plot of the risk of bias of those studies investigating sex as a risk factor of long COVID-19 [1,32,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56].

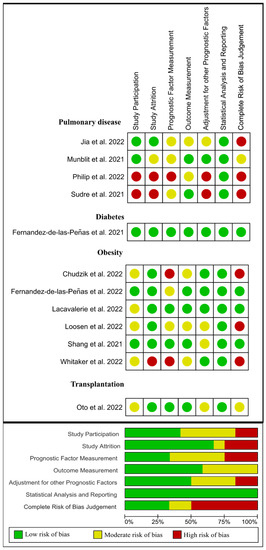

Lastly, from 12 papers evaluating previous medical comorbidities as a risk factor [29,39,44,52,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63], four [57,58,59,61] were classified as low risk of bias (green), two [52,62] as moderate risk of bias (yellow), and the remaining six [29,39,44,56,60,63] as high risk of bias (red). Figure 7 visually graphs that the most frequent risk of bias in this group of studies was concerned prognostic factor measurement (i.e., if the prognostic factors were measured in a similar way for all the participants).

Figure 7.

Plot of the risk of bias of those studies investigating medical comorbidities as a risk factor of long COVID-19 [4,29,39,44,52,53,56,58,60,61,62,63].

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis explored the association of long COVID-19 with risk factors not directly related to an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (i.e., pre-infection factors), including age, sex, or previous comorbidities. The results support that female sex may be a predictor of long COVID-19 while old age was reported to be associated with long COVID-19 in single studies; however, the pooled evidence was not significant. Finally, prior medical comorbidities can also be potential predictors of long COVID-19 symptoms. These results should be considered with caution because most studies exhibited moderate to high risk of bias.

4.1. Old Age and Long COVID-19

Old age is an important risk factor of poor outcomes in COVID-19 hospitalization [64]; however, the impact of age on long COVID-19 is controversial. Old age is associated with higher risk of long COVID-19 symptomatology in single studies and in two previous reviews [10,12], but not in the meta-analysis by Maglietta et al. [11]. Results from our qualitative analysis suggest that older adults can develop more long COVID-19 symptoms than younger adults; however, this assumption was not supported when pooling data into a meta-analysis. We conducted two meta-analyses, the first one categorizing those adults older than 60 years (Figure 2), and a second one considering age as a continuous variable (Figure 3); neither analysis revealed an association between old age and risk of developing long COVID-19. Nevertheless, the number of studies pooled in our analyses of age was notably limited (n = 3). Our data are consistent with the meta-analysis of Maglietta et al. [11] but disagree with Thompson et al. [12]. Several differences can explain the discrepancy with Thompson et al. [12]. It is possible that the use of a different definition of long COVID-19 by these authors [12] can lead to inconclusive comparisons of results. In addition, Thompson et al. [12] did not pool data of age and long COVID-19 into a meta-analysis, but only calculated regression of proportions of subjects at each age group developing long COVID-19 symptoms. The significance of old age as a risk factor for long COVID-19 development requires further investigation. In fact, just three out of eighteen papers (16%) analyzing age as prognostic factor showed low risk of bias. The most significant bias of these studies was the proper control of other cofounding factors observed in older people, i.e., higher presence of medical comorbidities, or longer hospitalization stay, which can also be associated with long COVID-19.

4.2. Female Sex and Long COVID-19

Sex is another important risk factor which has been studied in relation to COVID-19 and long COVID-19. Evidence supports that men and women exhibit the same probability of being infected by SARS-CoV-2; however, males are at a higher risk of worse outcomes and death than females during the acute phase of infection [65]. Results from our systematic review and meta-analysis support that female sex may be associated with higher risk of developing long COVID-19 (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.86). Our results are similar to those previously observed by Maglietta et al. [11], who also reported that female sex was associated with long COVID-19 symptoms (OR1.52, 95% CI 1.27–1.82), and with results (OR1.60, 95% CI 1.23–2.07) previously reported by Thompson et al. [12]. Based on available data, females are more vulnerable to develop long COVID-19 than males. Hence, considering sex differences in diagnosis, prevention and treatment are necessary, and fundamental steps towards precision medicine in COVID-19 [66]. Biological (i.e., hormones and immune responses), and sociocultural (i.e., sanitary-related behaviors, psychological stress, and inactivity) aspects play a significant role in creating sex-differences in long COVID-19 symptoms [48], although mechanisms behind increased risk of long COVID-19 in females remain unknown and warrant investigation.

4.3. Medical Comorbidities and Long COVID-19

Such as with old age, the presence of prior medical comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, obesity, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cardiovascular disease) is known to induce a more severe COVID-19 disease progression [67,68]. A potential reason is that such comorbidities can contribute to degradation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Since the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses this receptor as entry pathway in host cells, higher degradation of ACE2 could lead to a long-lasting inflammatory cytokine storm, oxidative stress, and hemostasis activation, which are all hallmarks of severe/critical COVID-19 illness [69]. Nevertheless, this hypothesis is not yet supported by the literature.

The current qualitative analysis suggests that prior comorbidities may contribute the risk of developing long COVID-19. Among different comorbidities, obesity seems to be associated; however, this assumption should be considered with caution at this stage, since potential cofounding factors, particularly those related to hospitalization (obese patients have more severe COVID-19 disease and higher hospitalization rates than non-obese patients), were not properly controlled in these studies. Moreover, the association of long COVID-19 with other medical comorbidities such as diabetes or transplants was only investigated in one prior study.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis should be considered according to potential strengths and limitations. Among the strengths, we conducted a systematic search of all the currently available evidence on factor not related to an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection but associated with higher risk of developing long COVID-19. This led to identification of thirty-eight studies. Second, this is the first time that several medical comorbidities have been systematically investigated as risk factors of long COVID-19.

One of the limitations is the lack of a consistent definition of long COVID-19 in available literatures. We included all identified studies within the qualitative analysis, but only those using the definition by Soriano et al. [2] of long COVID-19 were included in the meta-analyses. This assumption led to a small number of studies in the meta-analyses. Future studies using a more consistent definition of long COVID-19 are needed for improved quantification of the results. Another limitation is the lack of differentiation of risk factors between hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Similarly, no study investigating risk factors considered the SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Therefore, studies identifying long COVID-19 risk factors not directly associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection differentiating between hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients, and among different SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern are now needed. Finally, it should be considered that this systematic review and meta-analysis only investigated risk factors not associated with an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Other potential SARS-CoV-2-associated factors, such as severity of disease during the acute phase of infection or the number of COVID-19-associated onset symptoms have also been preliminarily identified as risk factors associated with long COVID-19 symptoms, particularly with respiratory symptoms [11]. Similarly, it is possible that some long COVID-19 symptoms can also be related to hospitalization factors which were also not investigated in this review.

5. Conclusions

The current review demonstrates that female sex and previous medical comorbidities may be predisposing factors for the development of long COVID-19 symptomatology. The current literature does not conclusively confirm that old age would significantly influence long COVID-19 risk. These results should be considered with caution due to moderate to high risk of bias in most published studies. These findings highlight the need for further research with improved control of confounding factors and use of a consistent and validated definition of long COVID-19.

Author Contributions

All the authors cited in the manuscript had substantial contributions to the concept and design, the execution of the work, or the analysis and interpretation of data; drafting or revising the manuscript and have read and approved the final version of the paper. K.I.N.: conceptualization, visualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, writing—review and editing. M.H.S.d.O.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. P.J.P.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. J.V.V.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. I.M.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. A.T.V.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. F.C.P.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. A.P.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. N.G.: writing—review and editing. D.K.: writing—review and editing. M.M.L.G.: writing—review and editing. J.L.: writing—review and editing. G.L.: writing—review and editing. B.M.H.: writing—review and editing. C.F.-d.-l.-P.: conceptualization, visualization, validation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was supported by a grant associated to the Fondo Europeo De Desarrollo Regional—Recursos REACT-UE del Programa Operativo de Madrid 2014–2020, en la línea de actuación de proyectos de I+D+i en materia de respuesta a COVID-19 (LONG COVID-19-EXP-CM). The sponsor had no role in the design, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, draft, review, or approval of the manuscript or its content. The authors were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, and the sponsor did not participate in this decision.

Data Availability Statement

All data derived from the study are included in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C. Long COVID: Current Definition. Infection 2022, 50, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. A Clinical Case Definition of Post-COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Zheng, B.; Daines, L.; Sheikh, A. Long-Term Sequelae of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of One-Year Follow-Up Studies on Post-COVID Symptoms. Pathogens 2022, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Florencio, L.L.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Navarro-Santana, M. Prevalence of Post-COVID-19 Symptoms in Hospitalized and Non-Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 92, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Haupert, S.R.; Zimmermann, L.; Shi, X.; Fritsche, L.G.; Mukherjee, B. Global Prevalence of Post COVID-19 Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, S.J. Long COVID or Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: Putative Pathophysiology, Risk Factors, and Treatments. Infect. Dis. 2021, 53, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crook, H.; Raza, S.; Nowell, J.; Young, M.; Edison, P. Long Covid-Mechanisms, Risk Factors, and Management. BMJ 2021, 374, n1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarialiabad, H.; Taghrir, M.H.; Abdollahi, A.; Ghahramani, N.; Kumar, M.; Paydar, S.; Razani, B.; Mwangi, J.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Malekmakan, L.; et al. Long COVID, a Comprehensive Systematic Scoping Review. Infection 2021, 49, 1163–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, F.M.; Lam, K.; Sounderajah, V.; Clarke, J.M.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A. Characteristics and Predictors of Acute and Chronic Post-COVID Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 36, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglietta, G.; Diodati, F.; Puntoni, M.; Lazzarelli, S.; Marcomini, B.; Patrizi, L.; Caminiti, C. Prognostic Factors for Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E.J.; Williams, D.M.; Walker, A.J.; Mitchell, R.E.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Yang, T.C.; Huggins, C.F.; Kwong, A.S.F.; Silverwood, R.J.; Di Gessa, G.; et al. Long COVID Burden and Risk Factors in 10 UK Longitudinal Studies and Electronic Health Records. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overview|COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19|Guidance|NICE. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, R.D.; Moons, K.G.M.; Snell, K.I.E.; Ensor, J.; Hooft, L.; Altman, D.G.; Hayden, J.; Collins, G.S.; Debray, T.P.A. A Guide to Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prognostic Factor Studies. BMJ 2019, 364, k4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.A.; van der Windt, D.A.; Cartwright, J.L.; Côté, P.; Bombardier, C. Assessing Bias in Studies of Prognostic Factors. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooten, W.J.A.; Tseli, E.; Äng, B.O.; Boersma, K.; Stålnacke, B.-M.; Gerdle, B.; Enthoven, P. Elaborating on the Assessment of the Risk of Bias in Prognostic Studies in Pain Rehabilitation Using QUIPS-Aspects of Interrater Agreement. Diagn. Progn. Res. 2019, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosato, M.; Carfì, A.; Martis, I.; Pais, C.; Ciciarello, F.; Rota, E.; Tritto, M.; Salerno, A.; Zazzara, M.B.; Martone, A.M.; et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Persistence of COVID-19 Symptoms in Older Adults: A Single-Center Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1840–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanichkachorn, G.; Newcomb, R.; Cowl, C.T.; Murad, M.H.; Breeher, L.; Miller, S.; Trenary, M.; Neveau, D.; Higgins, S. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome (Long Haul Syndrome): Description of a Multidisciplinary Clinic at Mayo Clinic and Characteristics of the Initial Patient Cohort. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat Larijani, M.; Ashrafian, F.; Bagheri Amiri, F.; Banifazl, M.; Bavand, A.; Karami, A.; Asgari Shokooh, F.; Ramezani, A. Characterization of Long COVID-19 Manifestations and Its Associated Factors: A Prospective Cohort Study from Iran. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 169, 105618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Burdens of Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 by Severity of Acute Infection, Demographics and Health Status. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocsovszky, Z.; Otohal, J.; Berényi, B.; Juhász, V.; Skoda, R.; Bokor, L.; Dohy, Z.; Szabó, L.; Nagy, G.; Becker, D.; et al. The Associations of Long-COVID Symptoms, Clinical Characteristics and Affective Psychological Constructs in a Non-Hospitalized Cohort. Physiol. Int. 2022, 109, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhadedy, M.A.; Marie, Y.; Halawa, A. COVID-19 in Renal Transplant Recipients: Case Series and a Brief Review of Current Evidence. NEF 2021, 145, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qui, L.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, G.; Chen, Z.; Ming, C.; Lu, X.; Gong, N. Long-Term Clinical and Immunological Impact of Severe COVID-19 on a Living Kidney Transplant Recipient—A Case Report. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoori, S.; Rossi, R.E.; Citterio, D.; Mazzaferro, V. COVID-19 in Long-Term Liver Transplant Patients: Preliminary Experience from an Italian Transplant Centre in Lombardy. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol 2020, 5, 532–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Munblit, D.; Pazukhina, E.; Ricchiuto, A.; Sinatti, D.; Zona, M.; De Matteis, A.; D’Ilario, F.; Gentili, C.; Lanni, R.; et al. Post-COVID Condition in Adults and Children Living in the Same Household in Italy: A Prospective Cohort Study Using the ISARIC Global Follow-Up Protocol. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yellumahanthi, D.K.; Barnett, B.; Barnett, S.; Yellumahanthi, S. COVID-19 Infection: Its Lingering Symptoms in Adults. Cureus 2022, 14, e24736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-Month Consequences of COVID-19 in Patients Discharged from Hospital: A Cohort Study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.S.; Penfold, R.S.; Bowyer, R.C.; Pujol, J.C.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Canas, L.S.; et al. Attributes and Predictors of Long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Nemati, H.; Shahisavandi, M.; Akbari, A.; Emami, A.; Lotfi, M.; Rostamihosseinkhani, M.; Barzegar, Z.; Kabiri, M.; Zeraatpisheh, Z.; et al. Long COVID in Children and Adolescents. World J. Pediatr. 2021, 17, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Dercon, Q.; Luciano, S.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Harrison, P.J. Incidence, Co-Occurrence, and Evolution of Long-COVID Features: A 6-Month Retrospective Cohort Study of 273,618 Survivors of COVID-19. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peghin, M.; Palese, A.; Venturini, M.; De Martino, M.; Gerussi, V.; Graziano, E.; Bontempo, G.; Marrella, F.; Tommasini, A.; Fabris, M.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Symptoms 6 Months after Acute Infection among Hospitalized and Non-Hospitalized Patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho-Schneider, C.; Laurent, E.; Lemaignen, A.; Beaufils, E.; Bourbao-Tournois, C.; Laribi, S.; Flament, T.; Ferreira-Maldent, N.; Bruyère, F.; Stefic, K.; et al. Follow-up of Adults with Noncritical COVID-19 Two Months after Symptom Onset. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, A.; Iqbal, K.; Arshad Ali, S.; Azim, D.; Farid, E.; Baig, M.D.; Bin Arif, T.; Raza, M. The COVID-19 Sequelae: A Cross-Sectional Evaluation of Post-Recovery Symptoms and the Need for Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Survivors. Cureus 2021, 13, e13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleyjeh, I.M.; Saddik, B.; AlSwaidan, N.; AlAnazi, A.; Ramakrishnan, R.K.; Alhazmi, D.; Aloufi, A.; AlSumait, F.; Berbari, E.; Halwani, R. Prevalence and Predictors of Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome (PACS) after Hospital Discharge: A Cohort Study with 4 Months Median Follow-Up. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmanov, I.M.; Spiridonova, E.; Bobkova, P.; Gamirova, A.; Shikhaleva, A.; Andreeva, M.; Blyuss, O.; El-Taravi, Y.; DunnGalvin, A.; Comberiati, P.; et al. Risk Factors for Post-COVID-19 Condition in Previously Hospitalised Children Using the ISARIC Global Follow-up Protocol: A Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 59, 2101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, E.; Mirandola, M.; Mazzaferri, F.; Dossi, G.; Razzaboni, E.; Zaffagnini, A.; Ivaldi, F.; Visentin, A.; Lambertenghi, L.; Arena, C.; et al. Determinants of Persistence of Symptoms and Impact on Physical and Mental Wellbeing in Long COVID: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Infect. 2022, 84, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Miranda, D.A.P.; Gomes, S.V.C.; Filgueiras, P.S.; Corsini, C.A.; Almeida, N.B.F.; Silva, R.A.; Medeiros, M.I.V.A.R.C.; Vilela, R.V.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Grenfell, R.F.Q. Long COVID-19 Syndrome: A 14-Months Longitudinal Study during the Two First Epidemic Peaks in Southeast Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loosen, S.H.; Jensen, B.-E.O.; Tanislav, C.; Luedde, T.; Roderburg, C.; Kostev, K. Obesity and Lipid Metabolism Disorders Determine the Risk for Development of Long COVID Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study from 50,402 COVID-19 Patients. Infection 2022, 50, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messin, L.; Puyraveau, M.; Benabdallah, Y.; Lepiller, Q.; Gendrin, V.; Zayet, S.; Klopfenstein, T.; Toko, L.; Pierron, A.; Royer, P.-Y. COVEVOL: Natural Evolution at 6 Months of COVID-19. Viruses 2021, 13, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Chang, H.-H.; Kwon, K.T.; Hwang, S.; Bae, S. One Year Follow-Up of COVID-19 Related Symptoms and Patient Quality of Life: A Prospective Cohort Study. Yonsei Med. J. 2022, 63, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Hughes, S.; Myles, P.; Williams, T.; Gokhale, K.M.; Taverner, T.; Chandan, J.S.; Brown, K.; Simms-Williams, N.; et al. Symptoms and Risk Factors for Long COVID in Non-Hospitalized Adults. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmsdal, G.; Hanusson, K.D.; Kristiansen, M.F.; Foldbo, B.M.; Danielsen, M.E.; Steig, B.Á.; Gaini, S.; Strøm, M.; Weihe, P.; Petersen, M.S. Long COVID in the Long Run—23-Month Follow-up Study of Persistent Symptoms. Open Forum. Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, K.E.J.; Buttery, S.; Williams, P.; Vijayakumar, B.; Tonkin, J.; Cumella, A.; Renwick, L.; Ogden, L.; Quint, J.K.; Johnston, S.L.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on People with Asthma: A Mixed Methods Analysis from a UK Wide Survey. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2022, 9, e001056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigfrid, L.; Drake, T.M.; Pauley, E.; Jesudason, E.C.; Olliaro, P.; Lim, W.S.; Gillesen, A.; Berry, C.; Lowe, D.J.; McPeake, J.; et al. Long Covid in Adults Discharged from UK Hospitals after Covid-19: A Prospective, Multicentre Cohort Study Using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 8, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgranges, F.; Tadini, E.; Munting, A.; Regina, J.; Filippidis, P.; Viala, B.; Karachalias, E.; Suttels, V.; Haefliger, D.; Kampouri, E.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome in Outpatients: A Cohort Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1943–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelà, G.; Goldoni, M.; Solinas, E.; Cavalli, C.; Tagliaferri, S.; Ranzieri, S.; Frizzelli, A.; Marchi, L.; Mori, P.A.; Majori, M.; et al. Sex-Related Differences in Long-COVID-19 Syndrome. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhard, C.E.; Sütsch, C.; Bengs, S.; Todorov, A.; Deforth, M.; Buehler, K.P.; Meisel, A.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Brugger, S.D.; et al. Understanding the Impact of Sociocultural Gender on Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19: A Bayesian Approach. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleyjeh, I.M.; Saddik, B.; Ramakrishnan, R.K.; AlSwaidan, N.; AlAnazi, A.; Alhazmi, D.; Aloufi, A.; AlSumait, F.; Berbari, E.F.; Halwani, R. Long Term Predictors of Breathlessness, Exercise Intolerance, Chronic Fatigue and Well-Being in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Cohort Study with 4 Months Median Follow-Up. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 15, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Abellán, J.; Padilla, S.; Fernández-González, M.; García, J.A.; Agulló, V.; Andreo, M.; Ruiz, S.; Galiana, A.; Gutiérrez, F.; Masiá, M. Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Is Associated with Long-Term Clinical Outcome in Patients with COVID-19: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 41, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Akbari, A.; Emami, A.; Lotfi, M.; Rostamihosseinkhani, M.; Nemati, H.; Barzegar, Z.; Kabiri, M.; Zeraatpisheh, Z.; Farjoud-Kouhanjani, M.; et al. Risk Factors Associated with Long COVID Syndrome: A Retrospective Study. Iran J. Med. Sci. 2021, 46, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munblit, D.; Bobkova, P.; Spiridonova, E.; Shikhaleva, A.; Gamirova, A.; Blyuss, O.; Nekliudov, N.; Bugaeva, P.; Andreeva, M.; DunnGalvin, A.; et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Persistent Symptoms in Adults Previously Hospitalized for COVID-19. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Martín-Guerrero, J.D.; Pellicer-Valero, Ó.J.; Navarro-Pardo, E.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Arias-Navalón, J.A.; Cigarán-Méndez, M.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Female Sex Is a Risk Factor Associated with Long-Term Post-COVID Related-Symptoms but Not with COVID-19 Symptoms: The LONG-COVID-EXP-CM Multicenter Study. JCM 2022, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, F.; Tomasoni, D.; Falcinella, C.; Barbanotti, D.; Castoldi, R.; Mulè, G.; Augello, M.; Mondatore, D.; Allegrini, M.; Cona, A.; et al. Female Gender Is Associated with Long COVID Syndrome: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, e9–e611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudzik, M.; Lewek, J.; Kapusta, J.; Banach, M.; Jankowski, P.; Bielecka-Dabrowa, A. Predictors of Long COVID in Patients without Comorbidities: Data from the Polish Long-COVID Cardiovascular (PoLoCOV-CVD) Study. JCM 2022, 11, 4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudzik, M.; Babicki, M.; Kapusta, J.; Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż.; Kołat, D.; Jankowski, P.; Mastalerz-Migas, A. Long-COVID Clinical Features and Risk Factors: A Retrospective Analysis of Patients from the STOP-COVID Registry of the PoLoCOV Study. Viruses 2022, 14, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Guijarro, C.; Torres-Macho, J.; Velasco-Arribas, M.; Plaza-Canteli, S.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Arias-Navalón, J.A. Diabetes and the Risk of Long-Term Post-COVID Symptoms. Diabetes 2021, 70, 2917–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhou, F.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S. Long-term Effects of Obesity on COVID-19 Patients Discharged from Hospital. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2021, 9, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Torres-Macho, J.; Elvira-Martínez, C.M.; Molina-Trigueros, L.J.; Sebastián-Viana, T.; Hernández-Barrera, V. Obesity Is Associated with a Greater Number of Long-term Post-COVID Symptoms and Poor Sleep Quality: A Multicentre Case-control Study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Cao, S.; Lee, A.S.; Manohar, M.; Sindher, S.B.; Ahuja, N.; Artandi, M.; Blish, C.A.; Blomkalns, A.L.; Chang, I.; et al. Anti-Nucleocapsid Antibody Levels and Pulmonary Comorbid Conditions Are Linked to Post–COVID-19 Syndrome. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e156713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacavalerie, M.R.; Pierre-Francois, S.; Agossou, M.; Inamo, J.; Cabie, A.; Barnay, J.L.; Neviere, R. Obese Patients with Long COVID-19 Display Abnormal Hyperventilatory Response and Impaired Gas Exchange at Peak Exercise. Future Cardiol. 2022, 18, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oto, O.A.; Ozturk, S.; Arici, M.; Velioğlu, A.; Dursun, B.; Guller, N.; Şahin, İ.; Eser, Z.E.; Paydaş, S.; Trabulus, S.; et al. Middle-Term Outcomes in Renal Transplant Recipients with COVID-19: A National, Multicenter, Controlled Study. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitaker, M.; Elliott, J.; Chadeau-Hyam, M.; Riley, S.; Darzi, A.; Cooke, G.; Ward, H.; Elliott, P. Persistent COVID-19 Symptoms in a Community Study of 606,434 People in England. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ashcroft, T.; Chung, A.; Dighero, I.; Dozier, M.; Horne, M.; McSwiggan, E.; Shamsuddin, A.; Nair, H. Risk Factors for Poor Outcomes in Hospitalised COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 10001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, A.K.; Mathew, R.; Aggarwal, P.; Nayer, J.; Bhoi, S.; Satapathy, S.; Ekka, M. Clinical Determinants of Severe COVID-19 Disease—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2021, 13, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Bairey Merz, N.; Barnes, P.J.; Brinton, R.D.; Carrero, J.-J.; DeMeo, D.L.; De Vries, G.J.; Epperson, C.N.; Govindan, R.; Klein, S.L.; et al. Sex and Gender: Modifiers of Health, Disease, and Medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abumweis, S.; Alrefai, W.; Alzoughool, F. Association of Obesity with COVID-19 Diseases Severity and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Studies. Obes. Med. 2022, 33, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Peng, Y.; Wu, X.; Pang, B.; Yang, F.; Zheng, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J. Comorbidities and Complications of COVID-19 Associated with Disease Severity, Progression, and Mortality in China with Centralized Isolation and Hospitalization: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 923485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yuan, X.; Gao, F.; Zhao, B.; Ding, L.; Huan, M.; Liu, C.; Jiang, L. High Number and Specific Comorbidities Could Impact the Immune Response in COVID-19 Patients. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 899930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).