Recent Progress in Fermentation of Asteraceae Botanicals: Sustainable Approaches to Functional Cosmetic Ingredients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Flavonoid Profile of Selected Species from the Asteraceae Family

3.1. Dandelion (T. officinale)—Flavonoids and Their Glycoside Forms

3.2. Milk Thistle (S. marianum)—Flavonoids and Their Glycoside Forms

3.3. Common Chamomile (M. chamomilla)—Flavonoids and Their Glycoside Forms

3.4. C. officinalis—Flavonoids and Their Glycoside Forms

3.5. A. montana—Flavonoids and Their Glycoside Forms

4. Biosynthesis and Biological Activity of Secondary Metabolites of Selected Plants from the Asteraceae Family

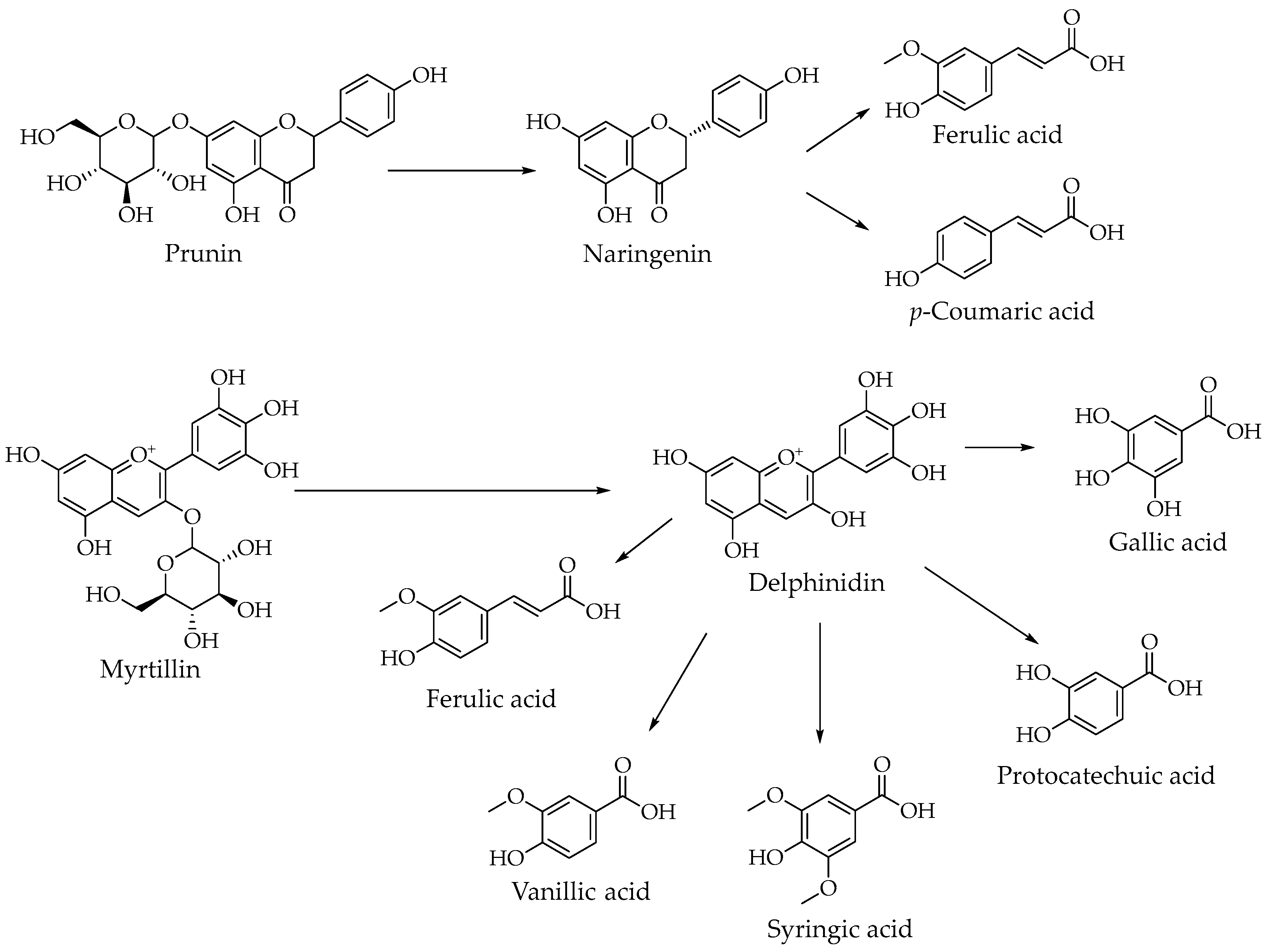

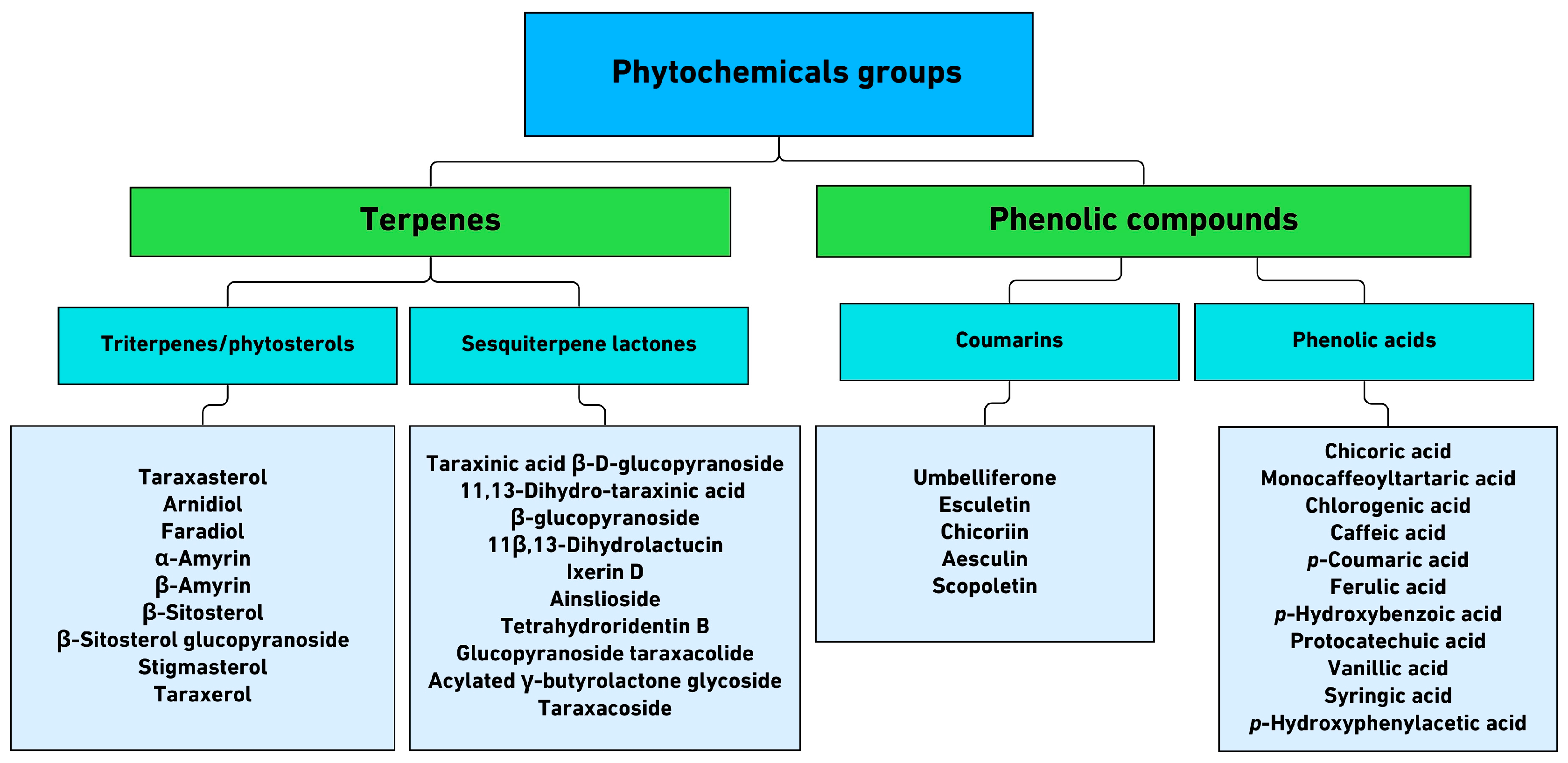

4.1. Dandelion: Biosynthesis, Chemical Composition and Pharmacological Significance

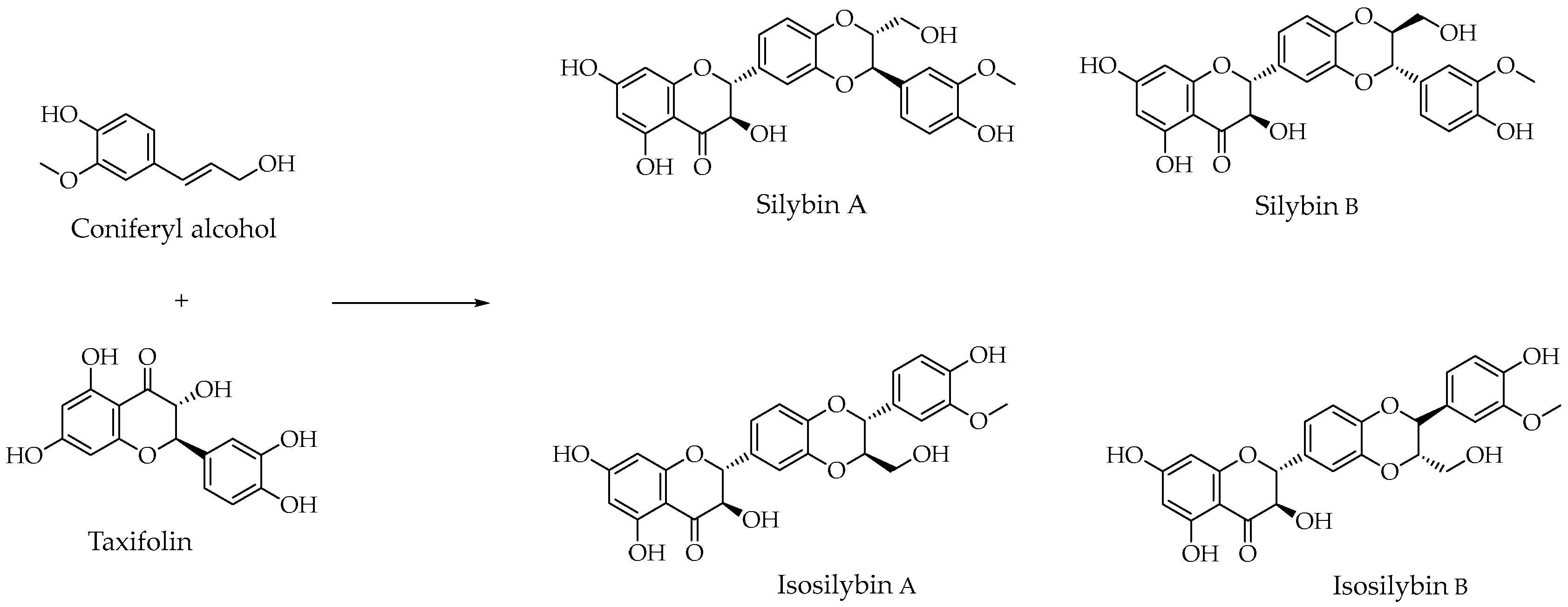

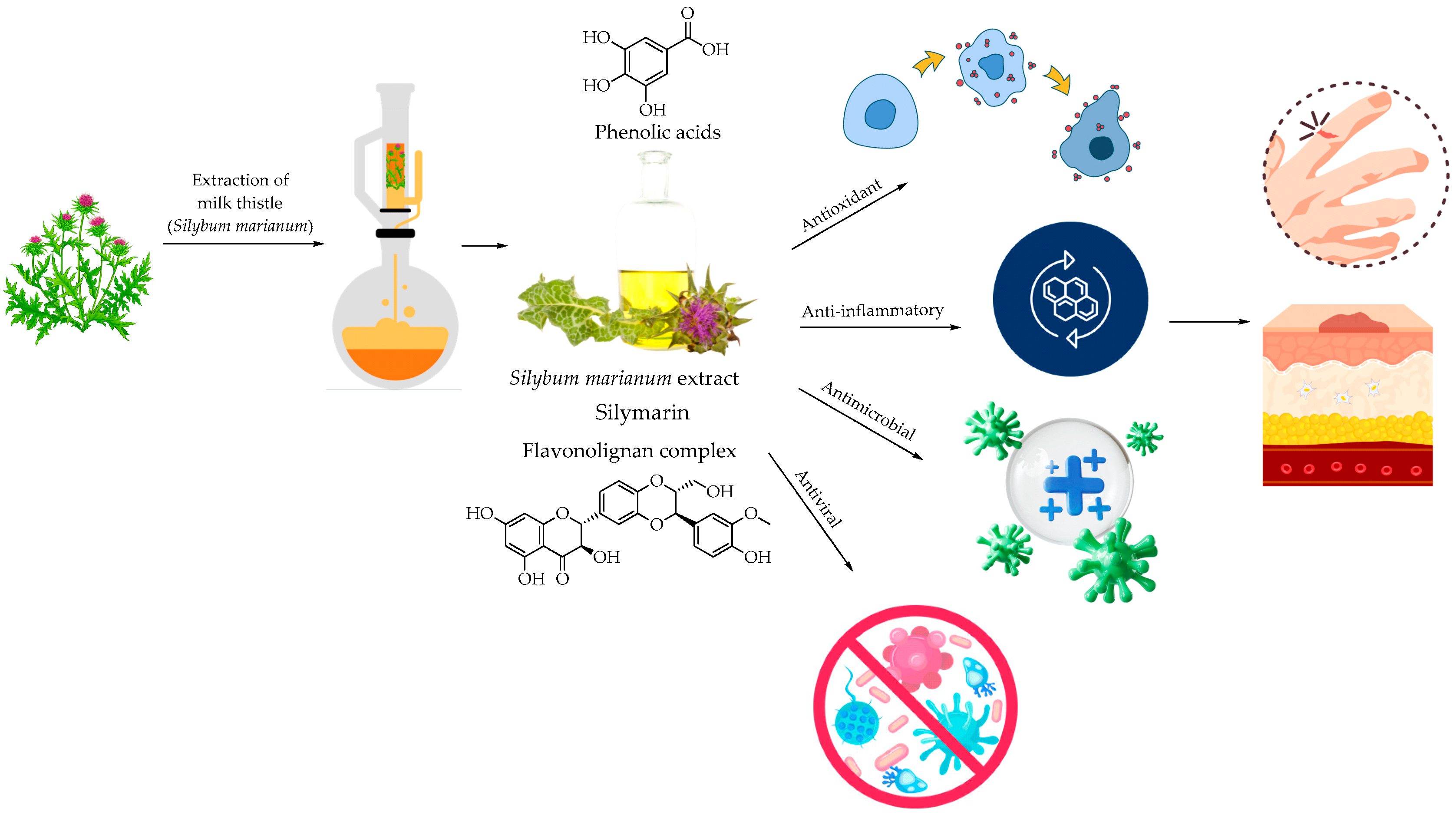

4.2. Milk Thistle: Biosynthesis, Chemistry of Silymarin, and Its Role in Medicine

4.3. Common Chamomile: Biosynthesis, Chemical Composition and Pharmacological Properties

4.4. C. officinalis: Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis Pathways, Phytochemical Composition and Pharmacological Activity

4.5. Mountain Arnica: Biosynthetic Pathways and Pharmacological Activity

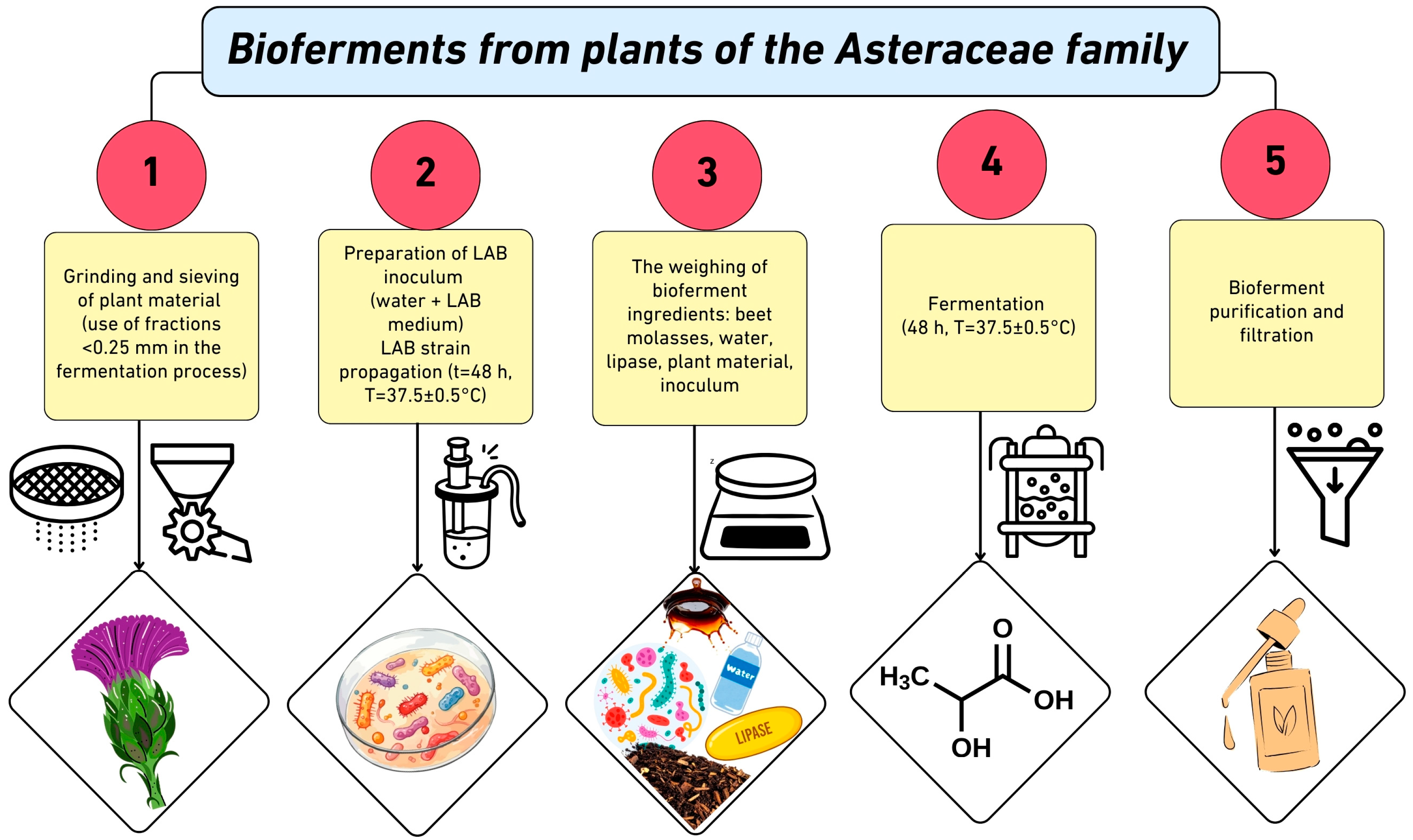

5. Biotechnological Transformation of Plant Raw Materials from the Asteraceae Family into Cosmetic Bioferments

5.1. Dandelion (T. officinale)

5.2. Fermentation of Asteraceae Plant Materials: Beyond T. officinale

5.3. Comparison of Cosmetics Containing Extracts from Plants of the Asteraceae Family and Other Botanical Raw Materials

6. Oxidative Stress, Antioxidants, and Methods for Assessing Their Activity

7. Environmental Impact of the Cosmetics Industry and Sustainable Solutions Under the European Green Deal

7.1. Biodegradability of Cosmetics—Definition, Significance, and Assessment Methods

7.2. Biodegradability, Microplastics and Technological Barriers in the Production of Natural Cosmetics

8. Conclusions

8.1. Summary and Implications

8.2. Evidence Gaps

8.3. Future Research Priorities

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majchrzak, W.; Motyl, I.; Śmigielski, K. Biological and Cosmetical Importance of Fermented Raw Materials: An Overview. Molecules 2022, 27, 4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżostan, M.; Wawrzyńczak, A.; Nowak, I. Use of Waste from the Food Industry and Applications of the Fermentation Process to Create Sustainable Cosmetic Products: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowska-Sieprawska, A.; Kiełbasa, A.; Rafińska, K.; Ligor, M.; Buszewski, B. Modern Methods of Pre-Treatment of Plant Material for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Kou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, H.; Chen, X.; Mao, S. Strategies and Industrial Perspectives to Improve Oral Absorption of Biological Macromolecules. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2018, 15, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, P.W. The Nature of the Epidermal Barrier: Biochemical Aspects. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1996, 18, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.; Manco, M.; Oresajo, C.; Baalbaki, N. Epidermal Barrier. In Cosmetic Dermatology; Draelos, Z.D., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-1-119-67683-6. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.-J. Fermented Foods and Food Microorganisms: Antioxidant Benefits and Biotechnological Advancements. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essmat, R.A.; Altalla, N.; Amen, R.A. Fermentation-Derived Compounds and Their Impact on Skin Health and Dermatology: A Review. Innov. Med. Omics 2024, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Hu, Y.; Wu, M.; Guo, M.; Wang, H. Biologically Active Components and Skincare Benefits of Rice Fermentation Products: A Review. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemlewska, A.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z.; Bujak, T.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Wójciak, M.; Sowa, I. Effect of Fermentation Time on the Content of Bioactive Compounds with Cosmetic and Dermatological Properties in Kombucha Yerba Mate Extracts. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemlewska, A.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Nowak, A.; Muzykiewicz-Szymańska, A.; Wójciak, M.; Sowa, I.; Szczepanek, D.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z. Enhancing the Cosmetic Potential of Aloe Vera Gel by Kombucha-Mediated Fermentation: Phytochemical Analysis and Evaluation of Antioxidant, Anti-Aging and Moisturizing Properties. Molecules 2025, 30, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek-Szczykutowicz, M.; Błońska-Sikora, E.M.; Kulik-Siarek, K.; Zhussupova, A.; Wrzosek, M. Bioferments and Biosurfactants as New Products with Potential Use in the Cosmetic Industry. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rivero, C.; López-Gómez, J.P. Unlocking the Potential of Fermentation in Cosmetics: A Review. Fermentation 2023, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Morya, S. Herbs of Asteraceae Family: Nutritional Profile, Bioactive Compounds, and Potentials in Therapeutics. In Harvesting Food from Weeds; Gupta, P., Chhikara, N., Panghal, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 21–78. ISBN 978-1-119-79197-3. [Google Scholar]

- Vijverberg, K.; Welten, M.; Kraaij, M.; van Heuven, B.J.; Smets, E.; Gravendeel, B. Sepal Identity of the Pappus and Floral Organ Development in the Common Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale; Asteraceae). Plants 2021, 10, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, J.; Abd Rani, N.Z.; Husain, K. A Review on the Potential Use of Medicinal Plants from Asteraceae and Lamiaceae Plant Family in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, A.; Olas, B. The Plants of the Asteraceae Family as Agents in the Protection of Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugier, P.; Kołos, A.; Wołkowycki, D.; Sugier, D.; Plak, A.; Sozinov, O. Evaluation of Species Inter-Relations and Soil Conditions in Arnica montana L. Habitats: A Step towards Active Protection of Endangered and High-Valued Medicinal Plant Species in NE Poland. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2018, 87, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, A.; Bononi, M.; Tateo, F.; Cocucci, M. Yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.) Growth at Different Altitudes in Central Italian Alps: Biomass Yield, Oil Content and Quality. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2005, 11, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdavoudi, H.; Ghorbanian, D.; Zarekia, S.; Soleiman, J.M.; Ghonchepur, M.; Sweeney, E.M.; Mastinu, A. Ecological Niche Modelling and Potential Distribution of Artemisia Sieberi in the Iranian Steppe Vegetation. Land 2022, 11, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Ullah, R.; Ali, K.; Jones, D.A.; Khan, M.E.H. Invasive Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn.) Causes Habitat Homogenization and Affects the Spatial Distribution of Vegetation in the Semi-Arid Regions of Northern Pakistan. Agriculture 2022, 12, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, A.S.; Fokina, A.D.; Milentyeva, I.S.; Asyakina, L.K.; Proskuryakova, L.A.; Prosekov, A.Y. The Biological Active Substances of Taraxacum officinale and Arctium Lappa from the Siberian Federal District. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwil, M.; Skoczylas, M.S. Biologically Active Compounds of Plant Origin in Medicine, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Lublinie: Lublin, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-7259-332-0. [Google Scholar]

- Žlabur, J.Š.; Žutić, I.; Radman, S.; Pleša, M.; Brnčić, M.; Barba, F.J.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Domínguez, R.; et al. Effect of Different Green Extraction Methods and Solvents on Bioactive Components of Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) Flowers. Molecules 2020, 25, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, F.M.; Pignone, D.; Laratta, B. The Mediterranean Species Calendula officinalis and Foeniculum Vulgare as Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds. Molecules 2024, 29, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekmine, S.; Benslama, O.; Ola, M.S.; Touzout, N.; Moussa, H.; Tahraoui, H.; Hafsa, H.; Zhang, J.; Amrane, A. Preliminary Data on Silybum marianum Metabolites: Comprehensive Characterization, Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Antimicrobial Activities, LC-MS/MS Profiling, and Predicted ADMET Analysis. Metabolites 2025, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.-C.; Lyu, H.-Y.; Wang, F.; Xiao, P.-G. Evaluating Potentials of Species Rich Taxonomic Groups in Cosmeticsand Dermatology: Clustering and Dispersion of Skin Efficacy of Asteraceae and Ranunculales Plants on the Species Phylogenetic Tree. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2023, 24, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Dong, M.; Liu, J.; Guo, N.; Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Y. Fermentation: Improvement of Pharmacological Effects and Applications of Botanical Drugs. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1430238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Song, M.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; An, X.; Qi, J. The Effects of Solid-State Fermentation on the Content, Composition and In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Flavonoids from Dandelion. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.R.; Macedo, J.A.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Macedo, G.A. Improving the Chemopreventive Potential of Orange Juice by Enzymatic Biotransformation. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Xie, K.; Liao, X.; Tan, J. Factors Affecting the Stability of Anthocyanins and Strategies for Improving Their Stability: A Review. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles Dorni, A.I.; Amalraj, A.; Gopi, S.; Varma, K.; Anjana, S.N. Novel Cosmeceuticals from Plants—An Industry Guided Review. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2017, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Kim, M. Antioxidant and Anti-Wrinkle Effects of Marigold Extract Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Sci. Preserv. 2025, 32, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Xu, X.; Guo, Z.; Meng, X.; Qian, G.; Li, H. Preparation of Safflower Fermentation Solution and Study on Its Biological Activity. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1472992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, E.; Grygorcewicz, B.; Spietelun, M.; Olszewska, P.; Bobkowska, A.; Ryglewicz, J.; Nowak, A.; Muzykiewicz-Szymańska, A.; Kucharski, Ł.; Pełech, R. Potential Role of Bioactive Compounds: In Vitro Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Fermented Milk Thistle. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhani, G.B.B.; Di Filippo, L.D.; De Paula, G.A.; Mantovanelli, V.R.; Da Fonseca, P.P.; Tashiro, F.M.; Monteiro, D.C.; Fonseca-Santos, B.; Duarte, J.L.; Chorilli, M. High-Tech Sustainable Beauty: Exploring Nanotechnology for the Development of Cosmetics Using Plant and Animal By-Products. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picken, C.A.R.; Buensoz, O.; Price, P.D.; Fidge, C.; Points, L.; Shaver, M.P. Sustainable Formulation Polymers for Home, Beauty and Personal Care: Challenges and Opportunities. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12926–12940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammala, A. Biodegradable Polymers as Encapsulation Materials for Cosmetics and Personal Care Markets. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 35, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecino, X.; Cruz, J.M.; Moldes, A.B.; Rodrigues, L.R. Biosurfactants in Cosmetic Formulations: Trends and Challenges. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacarias, C.H.; Paludetti, M.F.; De Oliveira, A.Á.S.; Federico, L.B. An Integrated Approach to Address the Biodegradability of Cosmetic Formulations as Part of a Corporate Sustainability Strategy. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2025, 47, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Rocchetti, G.; Chadha, S.; Zengin, G.; Bungau, S.; Kumar, A.; Mehta, V.; Uddin, M.S.; Khullar, G.; Setia, D.; et al. Phytochemicals from Plant Foods as Potential Source of Antiviral Agents: An Overview. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójciak, K.; Materska, M.; Pełka, A.; Michalska, A.; Małecka-Massalska, T.; Kačániová, M.; Čmiková, N.; Słowiński, M. Effect of the Addition of Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) on the Protein Profile, Antiradical Activity, and Microbiological Status of Raw-Ripening Pork Sausage. Molecules 2024, 29, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Zhang, Y. Dandelion (Taraxacum Genus): A Review of Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Effects. Molecules 2023, 28, 5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasa, M.-V.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Olariu, L.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S.; Lepadatu, A.-C.; Anghel, L.; Rosoiu, N. Bioactive Compounds from Vegetal Organs of Taraxacum Species (Dandelion) with Biomedical Applications: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathna, S.; Rupasinghe, H. Flavonoid Bioavailability and Attempts for Bioavailability Enhancement. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3367–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceddu, R.; Dinolfo, L.; Carrubba, A.; Sarno, M.; Di Miceli, G. Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum L.) as a Novel Multipurpose Crop for Agriculture in Marginal Environments: A Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L.; Capasso, R.; Milic, N.; Capasso, F. Milk Thistle in Liver Diseases: Past, Present, Future. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, S.; Imenshahidi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Karimi, G. Effects of Plant Extracts and Bioactive Compounds on Attenuation of Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzbowska, J.; Bowszys, T.; Sternik, P. Effect of a nitrogen fertilization rate on the yield and yield structure of milk thistle (Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn.). Ecol. Chem. Eng. A 2012, 19, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valková, V.; Ďúranová, H.; Bilčíková, J.; Habán, M. Milk thistle (Silybum marianum): A valuable medicinal plant with several therapeutic purposes. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2020, 9, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Barros, L.; Carvalho, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Infusions of Artichoke and Milk Thistle Represent a Good Source of Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horablaga, A.; Şibu, A.; Megyesi, C.I.; Gligor, D.; Bujancă, G.S.; Velciov, A.B.; Morariu, F.E.; Hădărugă, D.I.; Mişcă, C.D.; Hădărugă, N.G. Estimation of the Controlled Release of Antioxidants from β-Cyclodextrin/Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) or Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum L.), Asteraceae, Hydrophilic Extract Complexes through the Fast and Cheap Spectrophotometric Technique. Plants 2023, 12, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouet, S.; Leclerc, E.A.; Garros, L.; Tungmunnithum, D.; Kabra, A.; Abbasi, B.H.; Lainé, É.; Hano, C. A Green Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Optimization of the Natural Antioxidant and Anti-Aging Flavonolignans from Milk Thistle Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. Fruits for Cosmetic Applications. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, P.; Kong, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, W.; Ma, L.; Jiang, S.; Ren, W.; et al. A Review of the Botany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Synthetic Biology and Comprehensive Utilization of Silybum marianum. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1417655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, R.; Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A.; Kumari, A.; Rathore, S.; Kumar, R.; Singh, S. A Comprehensive Review on Biology, Genetic Improvement, Agro and Process Technology of German Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). Plants 2021, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mihyaoui, A.; Esteves Da Silva, J.C.G.; Charfi, S.; Candela Castillo, M.E.; Lamarti, A.; Arnao, M.B. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.): A Review of Ethnomedicinal Use, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Uses. Life 2022, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.-H.; Bae, W.-Y.; Eom, S.-J.; Kim, K.-T.; Paik, H.-D. Improved Antioxidative and Cytotoxic Activities of Chamomile (Matricaria Chamomilla) Florets Fermented by Lactobacillus Plantarum KCCM 11613P. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2017, 18, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.; Otto, L.-G. Matricaria recutita L.: True Chamomile. In Medicinal, Aromatic and Stimulant Plants; Handbook of Plant Breeding; Novak, J., Blüthner, W.-D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12, pp. 313–331. ISBN 978-3-030-38791-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, T.K. Matricaria chamomilla. In Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 397–431. ISBN 978-94-007-7394-3. [Google Scholar]

- Catani, M.V.; Rinaldi, F.; Tullio, V.; Gasperi, V.; Savini, I. Comparative Analysis of Phenolic Composition of Six Commercially Available Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) Extracts: Potential Biological Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, K.; Dong, L.; Ye, J.; Xu, F. Classification, Distribution, Biosynthesis, and Regulation of Secondary Metabolites in Matricaria chamomilla. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Bijak, M.; Saluk, J.; Ponczek, M.B.; Zbikowska, H.M.; Nowak, P.; Tsirigotis-Maniecka, M.; Pawlaczyk, I. Radical Scavenging and Antioxidant Effects of Matricaria chamomilla Polyphenolic–Polysaccharide Conjugates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.K. Calendula officinalis. In Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 213–244. ISBN 978-94-007-7394-3. [Google Scholar]

- Boztaş, G.; Bayram, E. Effects of Different Seeding Rates on Growth Performance, Yield, and Quality of Calendula officinalis L. in Mediterranean Conditions. Turk. J. Field Crops 2025, 30, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, T. Modern Methods of Standardization of Biologically Active Compounds of Medicinal Plant Raw Materials Calendulae Flos: Chemical Technologies, Analytical Indicators. SSP Mod. Pharm. Med. 2025, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Choubey, A.; Gupta, N.; Rajput, D.; Shukla, M.K. Boon Plant Calendula officinalis Linn. (CO): An Investigation, Ethnopharmacological, Phytoconstituent Review. Curr. Funct. Foods 2025, 3, e26668629298407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahane, K.; Kshirsagar, M.; Tambe, S.; Jain, D.; Rout, S.; Ferreira, M.K.M.; Mali, S.; Amin, P.; Srivastav, P.P.; Cruz, J.; et al. An Updated Review on the Multifaceted Therapeutic Potential of Calendula officinalis L. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwlayan, V.D.; Kumar, A.; Verma, M.; Garg, V.K.; Gupta, S. Therapeutic Potential of Calendula officinalis. Pharm. Pharmacol. Int. J. 2018, 6, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.J. Arnica montana L.: Doesn’t Origin Matter? Plants 2023, 12, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N.; Burgess, E.; Rodríguez Guitián, M.; Romero Franco, R.; López Mosquera, E.; Smallfield, B.; Joyce, N.; Littlejohn, R. Sesquiterpene Lactones in Arnica montana: Helenalin and Dihydrohelenalin chemotypes in Spain. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimel, K.; Godlewska, S.; Krauze-Baranowska, M.; Pobłocka-Olech, L. HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS Analysis of Arnica TM Constituents. Acta Pol. Pharm. Drug Res. 2019, 76, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merfort, I.; Wendisch, D. Flavonolglucuronide Aus Den Blüten von Arnica montana. Planta Med. 1988, 54, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, M.; Abrahamse, H.; George, B.P. Flavonoids: Antioxidant Powerhouses and Their Role in Nanomedicine. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriplani, P.; Guarve, K.; Baghael, U.S. Arnica montana L.—A Plant of Healing: Review. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 925–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugier, P.; Sugier, D.; Miazga-Karska, M.; Nurzyńska, A.; Król, B.; Sęczyk, Ł.; Kowalski, R. Effect of Different Arnica montana L. Plant Parts on the Essential Oil Composition, Antimicrobial Activity, and Synergistic Interactions with Antibiotics. Molecules 2025, 30, 3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharska, E.; Wachura, D.; Elchiev, I.; Bilewicz, P.; Gąsiorowski, M.; Pełech, R. Co-Fermentation of Dandelion Leaves (Taraxaci folium) as a Strategy for Increasing the Antioxidant Activity of Fermented Cosmetic Raw Materials—Current Progress and Prospects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, D.P.; Bipasha, A.S.; Thakur, J. The Therapeutic Value of Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale): A Full Review of Pharmacological Characteristics and Bioactive Component. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2025, 7, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailović, V.; Srećković, N.; Popović-Djordjević, J.B. Silybin and Silymarin: Phytochemistry, Bioactivity, and Pharmacology. In Handbook of Dietary Flavonoids; Xiao, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–45. ISBN 978-3-030-94753-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Z.; Luo, S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, W.; Lan, T.; He, R. Determination of Flavonolignan Compositional Ratios in Silybum marianum (Milk. Thistle) Extracts Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Molecules 2024, 29, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, Z.; Hanifian, H.; Nateghpour, M.; Hasanpour, G.; Raeisi, A.; Shabani, M.; Farivar, L.; Khezri, A.; Dehdast, S.A.; Shahsavari, S. Antimalarial Potential of Matricaria chamomilla-Derived MgO Nanoparticles against Plasmodium Falciparum Strains: An Experimental Study. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025, 25, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paut, A.; Guć, L.; Vrankić, M.; Crnčević, D.; Šenjug, P.; Pajić, D.; Odžak, R.; Šprung, M.; Nakić, K.; Marciuš, M.; et al. Plant-Mediated Synthesis of Magnetite Nanoparticles with Matricaria chamomilla Aqueous Extract. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Švehlíková, V.; Bennett, R.N.; Mellon, F.A.; Needs, P.W.; Piacente, S.; Kroon, P.A.; Bao, Y. Isolation, Identification and Stability of Acylated Derivatives of Apigenin 7-O-Glucoside from Chamomile (Chamomilla recutita [L.] Rauschert). Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2323–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, A.; Kirsipuu, K. Total Flavonoid Content in Varieties of Calendula officinalis L. Originating from Different Countries and Cultivated in Estonia. Nat. Prod. Product. Res. 2011, 25, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, N.; Rayamajhi, A.; Karki, D.; Pokhrel, T.; Adhikari, A. Arnica montana L.: Traditional Uses, Bioactive Chemical Constituents, and Pharmacological Activities. In Medicinal Plants of the Asteraceae Family; Devkota, H.P., Aftab, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 61–75. ISBN 978-981-19607-9-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X.; Shi, W.; Shen, T.; Cheng, X.; Wan, Q.; Fan, M.; Hu, D. Research Updates and Advances on Flavonoids Derived from Dandelion and Their Antioxidant Activities. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miean, K.H.; Mohamed, S. Flavonoid (Myricetin, Quercetin, Kaempferol, Luteolin, and Apigenin) Content of Edible Tropical Plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3106–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Luo, Y.; Yang, J.; Cheng, C. Botanical Flavonoids: Efficacy, Absorption, Metabolism and Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology for Improving Bioavailability. Molecules 2025, 30, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Shen, J.; Xu, H.; Li, K. Integrative Analysis of the Metabolome and Transcriptome Reveals the Mechanism of Polyphenol Biosynthesis in Taraxacum mongolicum. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1418585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esatbeyoglu, T.; Obermair, B.; Dorn, T.; Siems, K.; Rimbach, G.; Birringer, M. Sesquiterpene Lactone Composition and Cellular Nrf2 Induction of Taraxacum officinale Leaves and Roots and Taraxinic Acid β-d-Glucopyranosyl Ester. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savych, A.; Bilyk, O.; Vaschuk, V.; Humeniuk, I. Analysis of Inulin and Fructans in Taraxacum officinale L. Roots as the Main Inulin-Containing Component of Antidiabetic Herbal Mixture. Pharmacia 2021, 68, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Vielma, F.; Quiñones San Martin, M.; Muñoz-Carrasco, N.; Berrocal-Navarrete, F.; González, D.R.; Zúñiga-Hernández, J. The Role of Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in Liver Health and Hepatoprotective Properties. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, A.; Arif, A.; Zubair, A.; Kiran, S.; Shahid, M.N.; Hossain, B. Exploring the Phytochemistry and Therapeutic Potential of Indigenously Grown Taraxacum officinale Leaves. J. Chem. 2025, 2025, 4385247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surai, P.F. Silymarin as a Natural Antioxidant: An Overview of the Current Evidence and Perspectives. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 204–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrba, J.; Papoušková, B.; Kosina, P.; Lněničková, K.; Valentová, K.; Ulrichová, J. Identification of Human Sulfotransferases Active towards Silymarin Flavonolignans and Taxifolin. Metabolites 2020, 10, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Huang, S.-M.; Yen, G.-C. Silymarin: A Novel Antioxidant with Antiglycation and Antiinflammatory Properties In Vitro and In Vivo. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selc, M.; Babelova, A. Looking beyond Silybin: The Importance of Other Silymarin Flavonolignans. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1637393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijak, M. Silybin, a Major Bioactive Component of Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum L. Gaernt.)—Chemistry, Bioavailability, and Metabolism. Molecules 2017, 22, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selc, M.; Macova, R.; Babelova, A. Nanoparticle-Boosted Silymarin: Are We Overlooking Taxifolin and Other Key Components? Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1628672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wianowska, D.; Winiewski, M. Simplified Procedure of Silymarin Extraction from Silybum marianum L. Gaertner. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015, 53, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.Y.-W.; Liu, Y. Molecular Structure and Stereochemistry of Silybin A, Silybin B, Isosilybin A, and Isosilybin B, Isolated from Silybum m arianum (Milk Thistle). J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1171–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedermann, D.; Vavříková, E.; Cvak, L.; Křen, V. Chemistry of Silybin. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1138–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liang, L.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Zeng, J.; He, M.; Wei, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. A Comprehensive Exploration of Hydrogel Applications in Multi-Stage Skin Wound Healing. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 3745–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaei, T. The Treatment of Melasma by Silymarin Cream. BMC Dermatol. 2012, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boira, C.; Chapuis, E.; Scandolera, A.; Reynaud, R. Silymarin Alleviates Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Induced by UV and Air Pollution in Human Epidermis and Activates β-Endorphin Release through Cannabinoid Receptor Type 2. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorjay, K.; Arif, T.; Adil, M. Silymarin: An Interesting Modality in Dermatological Therapeutics. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2018, 84, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sapagh, S.; Allam, N.G.; El-Sayed, M.N.E.-D.; El-Hefnawy, A.A.; Korbecka-Glinka, G.; Shala, A.Y. Effects of Silybum marianum L. Seed Extracts on Multi Drug Resistant (MDR) Bacteria. Molecules 2023, 29, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, E.; Sarıtaş, S.; Duman, H.; Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Karav, S.; Witkowska, A.M. Polyphenols: Secondary Metabolites with a Biological Impression. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

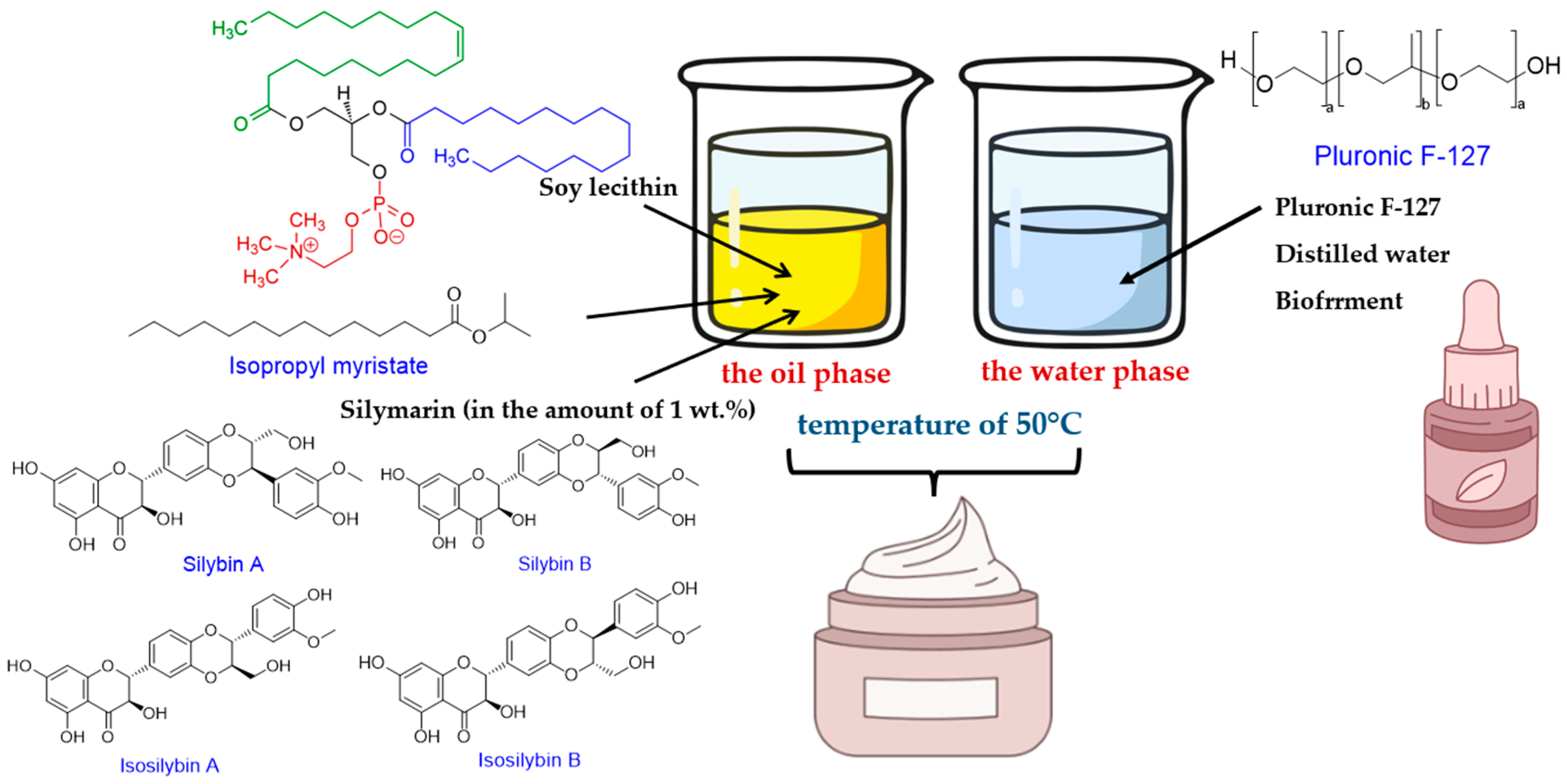

- Kucharska, E.; Sarpong, R.; Bobkowska, A.; Ryglewicz, J.; Nowak, A.; Kucharski, Ł.; Muzykiewicz-Szymańska, A.; Duchnik, W.; Pełech, R. Use of Silybum marianum Extract and Bio-Ferment for Biodegradable Cosmetic Formulations to Enhance Antioxidant Potential and Effect of the Type of Vehicle on the Percutaneous Absorption and Skin Retention of Silybin and Taxifolin. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligęza, M.; Wyglądacz, D.; Tobiasz, A.; Jaworecka, K.; Reich, A. Natural Cold Pressed Oils as Cosmetic Products. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Rev. 2016, 4, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A.; Ayub, H.; Sehrish, A.; Ambreen, S.; Khan, F.A.; Itrat, N.; Nazir, A.; Shoukat, A.; Shoukat, A.; Ejaz, A.; et al. Essential Components from Plant Source Oils: A Review on Extraction, Detection, Identification, and Quantification. Molecules 2023, 28, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutterodt, H.; Slavin, M.; Whent, M.; Turner, E.; Yu, L. Fatty Acid Composition, Oxidative Stability, Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Properties of Selected Cold-Pressed Grape Seed Oils and Flours. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudláčková, B.; Misák, P.; Pluháčková, H. Silymarin and Fatty Acid Profiles of Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum L.) Genotypes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2025, 80, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małajowicz, J.; Makouei, S.; Bryś, J. Analysis of the Physicochemical and Health-Promoting Properties of Milk Thistle Seeds Oil. Technol. Prog. Food Process. 2025, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saa, A. Effect of Silymarin as Natural Antioxidants and Antimicrobial Activity. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 95, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Ren, M.; Bao, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, N.; Sun, S.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; et al. From Medical Herb to Functional Food: Development of a Fermented Milk Containing Silybin and Protein from Milk Thistle. Foods 2023, 12, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makouie, S.; Bryś, J.; Małajowicz, J.; Koczoń, P.; Siol, M.; Palani, B.K.; Bryś, A.; Obranović, M.; Mikolčević, S.; Gruczyńska-Sękowska, E. A Comprehensive Review of Silymarin Extraction and Liposomal Encapsulation Techniques for Potential Applications in Food. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, D.V.; Ibáñez, E.; Reglero, G.; Fornari, T. Effect of Cosolvents (Ethyl Lactate, Ethyl Acetate and Ethanol) on the Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Caffeine from Green Tea. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 107, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Erşatır, M.; Poyraz, S.; Amangeldinova, M.; Kudrina, N.O.; Terletskaya, N.V. Green Extraction of Plant Materials Using Supercritical CO2: Insights into Methods, Analysis, and Bioactivity. Plants 2024, 13, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogorzelska-Nowicka, E.; Hanula, M.; Pogorzelski, G. Extraction of Polyphenols and Essential Oils from Herbs with Green Extraction Methods—An Insightful Review. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmy, J.; Greenfield, S.; Shindo, S.; Kawai, T.; Cervantes, J.; Hong, B.-Y. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Chamomile from Randomized Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Pharm. Biol. 2025, 63, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeedi, M.; Khanavi, M.; Shahsavari, K.; Manayi, A. Matricaria chamomilla: An Updated Review on Biological Activities of the Plant and Constituents. Res. J. Pharmacogn. 2024, 11, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, L.; Sözbilir, N.B. Effects of Matricaria chamomilla L. on Lipid Peroxidation, Antioxidant Enzyme Systems, and Key Liver Enzymes in CCl4 -Treated Rats. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2012, 94, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Niu, F.-J.; Li, K.-W.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.-Z.; Gao, L.-N. Chamomile: A Review of Its Traditional Uses, Chemical Constituents, Pharmacological Activities and Quality Control Studies. Molecules 2022, 28, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažeković, B.; Čičin-Mašansker, I.J.; Kindl, M.; Mahovlić, L.; Vladimir-Knežević, S. Chemometrically-Supported Quality Assessment of Chamomile Tea. Acta Pharm. 2025, 75, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šamec, D.; Karalija, E.; Šola, I.; Vujčić Bok, V.; Salopek-Sondi, B. The Role of Polyphenols in Abiotic Stress Response: The Influence of Molecular Structure. Plants 2021, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.-L.; Austin, M.B.; Stewart, C.; Noel, J.P. Structure and Function of Enzymes Involved in the Biosynthesis of Phenylpropanoids. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 46, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.-J.; Kwon, M.; Ro, D.-K.; Kim, S.-U. Enantioselective Microbial Synthesis of the Indigenous Natural Product (−)-α-Bisabolol by a Sesquiterpene Synthase from Chamomile (Matricaria recutita). Biochem. J. 2014, 463, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubova, D.; Salmon, M.; Su, H.; Tansley, C.; Kaithakottil, G.; Linsmith, G.; Schudoma, C.; Swarbreck, D.; O’Connell, M.; Patron, N. Biosynthesis and Bioactivity of Anti-Inflammatory Triterpenoids in Calendula officinalis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykłowska-Baranek, K.; Kamińska, M.; Pączkowski, C.; Pietrosiuk, A.; Szakiel, A. Metabolic Modifications in Terpenoid and Steroid Pathways Triggered by Methyl Jasmonate in Taxus × Media Hairy Roots. Plants 2022, 11, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Kashchenko, N.I.; Chirikova, N.K.; Akobirshoeva, A.; Zilfikarov, I.N.; Vennos, C. Isorhamnetin and Quercetin Derivatives as Anti-Acetylcholinesterase Principles of Marigold (Calendula officinalis) Flowers and Preparations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, V.L.; Gulyás-Fekete, G.; Nagy, V.; Zubay, P.; Szabó, K.; Sándor, V.; Agócs, A.; Deli, J. Carotenoid Composition of Calendula officinalis Flowers with Identification of the Configuration of 5,8-Epoxy-Carotenoids. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 1092–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Ferreira, M.S.; Sousa-Lobo, J.M.; Cruz, M.T.; Almeida, I.F. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Calendula officinalis L. Flower Extract. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragueto Escher, G.; do Carmo Cardoso Borges, L.; Sousa Santos, J.; Mendanha Cruz, T.; Boscacci Marques, M.; do Carmo, M.A.V.; Azevedo, L.; Furtado, M.M.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Wen, M.; et al. From the Field to the Pot: Phytochemical and Functional Analyses of Calendula officinalis L. Flower for Incorporation in an Organic Yogurt. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrl, J.; Piqué-Borràs, M.-R.; Jaklin, M.; Werner, M.; Werz, O.; Josef, H.; Hölz, H.; Ammendola, A.; Künstle, G. Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Arnica Montana Planta Tota versus Flower Extracts: Analytical, In Vitro and In Vivo Mouse Paw Oedema Model Studies. Plants 2023, 12, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, B.; Kosińska-Cagnazzo, A.; Schmitt, R.; Andlauer, W. Fermentation of Plant Material—Effect on Sugar Content and Stability of Bioactive Compounds. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2014, 64, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants: A Comprehensive Review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valanciene, E.; Jonuskiene, I.; Syrpas, M.; Augustiniene, E.; Matulis, P.; Simonavicius, A.; Malys, N. Advances and Prospects of Phenolic Acids Production, Biorefinery and Analysis. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.S. Natural Antioxidants: Sources, Compounds, Mechanisms of Action, and Potential Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011, 10, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.; Oliveira, H.; Fernandes, I.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Perez-Gregorio, R. Recent Advances in Extracting Phenolic Compounds from Food and Their Use in Disease Prevention and as Cosmetics. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1130–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováčik, J.; Dudáš, M.; Hedbavny, J.; Mártonfi, P. Dandelion Taraxacum linearisquameum Does Not Reflect Soil Metal Content in Urban Localities. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Mobasheri, L.; Rakhshandeh, H.; Rahimi, V.B.; Najafi, Z.; Askari, V.R. Edible Herbal Medicines as an Alternative to Common Medication for Sleep Disorders: A Review Article. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2024, 22, 1205–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, T.; Ávila-Gálvez, M.Á.; Mercier, S.; Vallejo, F.; Bred, A.; Fraisse, D.; Morand, C.; Pelvan, E.; Monfoulet, L.-E.; González-Sarrías, A. Impact of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation on (Poly) Phenolic Profile and In Vitro Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Herbal Infusions. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Shi, G.; Gu, J.; Du, J.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, S.; Jiang, J. Impact of Lactic Acid Bacterial Fermentation on the Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Capacities and Flavor Properties of Dandelion. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z.; Ziemlewska, A.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Mokrzyńska, A.; Wójciak, M.; Sowa, I. Apiaceae Bioferments Obtained by Fermentation with Kombucha as an Important Source of Active Substances for Skin Care. Molecules 2025, 30, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.; Banerjee, S.; Singh, A.; Kulhari, H.; Anand Saharan, V. From Traditional to Modern Medicine: The Role of Herbs and Phytoconstituents in Pharmaceuticals, Nutraceuticals, and Cosmetics. In Formulating Pharma-, Nutra-, and Cosmeceutical Products from Herbal Substances; Singh, A., Kulhari, H., Saharan, V.A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 3–73. ISBN 978-1-119-76947-7. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, E.; De Paepe, K.; Van De Wiele, T. Postbiotics and Their Health Modulatory Biomolecules. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, Y.; Rimbach, G.; Lüersen, K.; Vinderola, G.; Ipharraguerre, I.R. The Postbiotic Potential of Aspergillus oryzae—A Narrative Review. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1452725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Maalik, A.; Murtaza, G. Inhibitory Mechanism against Oxidative Stress of Caffeic Acid. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.; Aeri, V. Enhancement of Lutein Content in Calendula officinalis Linn. By Solid-State Fermentation with Lactobacillus Species. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 4794–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budan, A.; Bellenot, D.; Freuze, I.; Gillmann, L.; Chicoteau, P.; Richomme, P.; Guilet, D. Potential of Extracts from Saponaria officinalis and Calendula officinalis to Modulate in Vitro Rumen Fermentation with Respect to Their Content in Saponins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetanović, A.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Zeković, Z.; Savić, S.; Vulić, J.; Mašković, P.; Ćetković, G. Comparative Analysis of Antioxidant, Antimicrobiological and Cytotoxic Activities of Native and Fermented Chamomile Ligulate Flower Extracts. Planta 2015, 242, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetanović, A.; Zeković, Z.; Zengin, G.; Mašković, P.; Petronijević, M.; Radojković, M. Multidirectional Approaches on Autofermented Chamomile Ligulate Flowers: Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Cytotoxic and Enzyme Inhibitory Effects. South Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 120, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, V.; Borgonovo, G.; Giupponi, L.; Bassoli, A.; Pedrali, D.; Zuccolo, M.; Rodari, A.; Giorgi, A. Comparing Wild and Cultivated Arnica montana L. from the Italian Alps to Explore the Possibility of Sustainable Production Using Local Seeds. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, T.; Morita, T.; Konishi, M.; Imura, T.; Kitamoto, D. Characterization of New Glycolipid Biosurfactants, Tri-Acylated Mannosylerythritol Lipids, Produced by Pseudozyma Yeasts. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhai, L.; Liu, J.; Sun, G.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; et al. Screening and Research on Skin Barrier Damage Protective Efficacy of Different Mannosylerythritol Lipids. Molecules 2022, 27, 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, T.; Sansone, F.; Russo, P.; Picerno, P.; Aquino, R.P.; Gasparri, F.; Mencherini, T. A Water-Soluble Microencapsulated Milk Thistle Extract as Active Ingredient for Dermal Formulations. Molecules 2019, 24, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, A.; Akhtar, N. Anti-Aging Potential of a Cream Containing Milk Thistle Extract: Formulation and in Vivo Evaluation. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 1509–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbossa, W.A.C.; Maia Campos, P.M.B.G. Euterpe Oleracea, Matricaria chamomilla, and Camellia sinensis as Promising Ingredients for Development of Skin Care Formulations. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 83, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, P.; Gliszczyńska-Świgło, A.; Szymusiak, H. Protective Effect of Commercial Acerola, Willow, and Rose Extracts against Oxidation of Cosmetic Emulsions Containing Wheat Germ Oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2014, 116, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.; Boyer, I.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; et al. Amended Safety Assessment of Chamomilla recutita-Derived Ingredients as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2018, 37, 51S–79S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, S.; Reed, T.T.; Venditti, P.; Victor, V.M. Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1245049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, M.A.; Fasolin, L.H.; Picone, C.S.F.; Pastrana, L.M.; Cunha, R.L.; Vicente, A.A. Structural and Mechanical Properties of Organogels: Role of Oil and Gelator Molecular Structure. Food Res. Int. 2017, 96, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS Function in Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manful, C.F.; Fordjour, E.; Subramaniam, D.; Sey, A.A.; Abbey, L.; Thomas, R. Antioxidants and Reactive Oxygen Species: Shaping Human Health and Disease Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Jia, S.; Ding, Y.; Xia, S.; Giunta, S. Balanced Basal-Levels of ROS (Redox-Biology), and Very-Low-Levels of pro-Inflammatory Cytokines (Cold-Inflammaging), as Signaling Molecules Can Prevent or Slow-down Overt-Inflammaging, and the Aging-Associated Decline of Adaptive-Homeostasis. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 172, 112067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondet, V.; Brand-Williams, W.; Berset, C. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Antioxidant Activity Using the DPPH. Free Radical Method. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1997, 30, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissi, E.A.; Modak, B.; Torres, R.; Escobar, J.; Urzua, A. Total Antioxidant Potential of Resinous Exudates from Heliotrapium Species, and a Comparison of the ABTS and DPPH Methods. Free Radic. Res. 1999, 30, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.J.; Oldoni, T.L.C.; de Alencar, S.M.; Reis, A.; Loguercio, A.D.; Grande, R.H.M. Antioxidant Activity by DPPH Assay of Potential Solutions to Be Applied on Bleached Teeth. Braz. Dent. J. 2012, 23, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abideen, Z.; Qasim, M.; Rasheed, A.; Adnan, M.Y.; Gul, B.; Khan, M.A. Antioxidant activity and polyphenolic content of Phragmites karka under saline conditions. Pak. J. Bot. 2015, 47, 813–818. [Google Scholar]

- Vuolo, M.M.; Lima, V.S.; Maróstica Junior, M.R. Phenolic Compounds. In Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 33–50. ISBN 978-0-12-814774-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, N. Phenolic Acids: Natural Versatile Molecules with Promising Therapeutic Applications. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikiaris, N.; Nikolaidis, N.F.; Barmpalexis, P. Microplastics (MPs) in Cosmetics: A Review on Their Presence in Personal-Care, Cosmetic, and Cleaning Products (PCCPs) and Sustainable Alternatives from Biobased and Biodegradable Polymers. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, D. Sustainability in the Cosmetics Industry: Environmental Impacts, Statistics, and Solutions. In Current Approaches in Applied Statistics I; Tahtalı, Y., Demir, İ., Bayyurt, L., Eds.; Özgür Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2025; ISBN 9786255646941. [Google Scholar]

- Thormann, L.; Neuling, U.; Kaltschmitt, M. Opportunities and Challenges of the European Green Deal for the Chemical Industry: An Approach Measuring Circularity. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2023, 5, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, E.; Kovalevska, O. Sustainability in the European Union: Analyzing the Discourse of the European Green Deal. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couceiro, B.; Hameed, H.; Vieira, A.C.F.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Veiga, F.; Pires, P.C.; Ferreira, L.; Paiva-Santos, A.C. Promoting Health and Sustainability: Exploring Safer Alternatives in Cosmetics and Regulatory Perspectives. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 43, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohee, R.; Unmar, G.D.; Mudhoo, A.; Khadoo, P. Biodegradability of Biodegradable/Degradable Plastic Materials under Aerobic and Anaerobic Conditions. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, K.; González, M.; Kearns, P.; Sintes, J.R.; Rossi, F.; Sayre, P. Review of Achievements of the OECD Working Party on Manufactured Nanomaterials’ Testing and Assessment Programme. From Exploratory Testing to Test Guidelines. Regul. toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 74, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuschenbach, P.; Pagga, U.; Strotmann, U. A Critical Comparison of Respirometric Biodegradation Tests Based on OECD 301 and Related Test Methods. Water Res. 2003, 37, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.-F.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Long, W.-N.; Sun, G.-P.; Zeng, G.-Q.; Xu, M.-Y.; Luan, T.-G. A Comparative Study of Biodegradability of a Carcinogenic Aromatic Amine (4,4′-Diaminodiphenylmethane) with OECD 301 Test Methods. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 111, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmann, U.; Thouand, G.; Pagga, U.; Gartiser, S.; Heipieper, H.J. Toward the Future of OECD/ISO Biodegradability Testing-New Approaches and Developments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 2073–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.M.; Marto, J.M. A Sustainable Life Cycle for Cosmetics: From Design and Development to Post-Use Phase. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 35, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, O.; Băbeanu, N.E.; Popa, I.; Niță, S.; Dinu-Pârvu, C.E. Methods for Obtaining and Determination of Squalene from Natural Sources. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 367202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolaosho, T.L.; Rasaq, M.F.; Omotoye, E.V.; Araomo, O.V.; Adekoya, O.S.; Abolaji, O.Y.; Hungbo, J.J. Microplastics in Freshwater and Marine Ecosystems: Occurrence, Characterization, Sources, Distribution Dynamics, Fate, Transport Processes, Potential Mitigation Strategies, and Policy Interventions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Chen, C.; Ni, D.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Wang, L. Effects of Fermentation on Bioactivity and the Composition of Polyphenols Contained in Polyphenol-Rich Foods: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, S.; Mussatto, S.I.; Martínez-Avila, G.; Montañez-Saenz, J.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J.A. Bioactive Phenolic Compounds: Production and Extraction by Solid-State Fermentation. A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant | * Flavonoid Content (Total) | Main Flavonoids (Aglycones) | Glycosidic Forms of Flavonoids | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. officinale | 0.5–1.5% in leaves and flowers | Naringenin Delphinidin Quercetin Apigenin Luteolin | Prunin Myrtyllin Quercetin-3-rhamnoside Apigenin-7-O-glucoside Luteolin-7-O-glucoside | [76,77] |

| S. marianum | 0.1–0.3% flavonoids 2–3% flavonolignans | Quercetin Taxifolin Apigenin Luteolin | Rutin Isoquercitrin Apigenin-7-O-glucoside Luteolin-7-O-glucoside | [54,78,79] |

| M. chamomilla | 6–8% in baskets | Apigenin Luteolin Quercetin | Apigenin-7-O-glucoside luteolin glycosides | [80,81,82] |

| C. officinalis | 0.3–0.8% | Izorhamnetin Quercetin Apigenin (trace amounts) | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside Rutin, Isoquercitrin | [83] |

| A. montana | 0.4–0.6% | Quercetin Kaempferol Isorhamnetin Luteolin | Isoquercitrin Rutin Luteolin-7-O-glucoside | [84] |

| Number of Bioferment | Sugars: Beet Molasses/Cane Molasses | Water | Dandelion Leaf | * Inoculum: LAB/Yeast | Lipase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [g] | [g] | [g] | [mL] | [g] | |

| B-1 | 2.5/2.5 | 75 | 0.05 | 9/1 | 0.01 |

| B-2 | 2.5/2.5 | 75 | 2 | 9/1 | 0.01 |

| B-3 | 2.5/2.5 | 75 | 0.25 | 0.9/0.1 | 0.01 |

| B-4 | 2.5/2.5 | 75 | 0.25 | 22.5/2.5 | 0.01 |

| B-5 | 0.25/0.25 | 75 | 0.25 | 22.5/2.5 | 0.01 |

| B-6 | 7.5/7.5 | 75 | 0.25 | 22.5/2.5 | 0.01 |

| Step | Process Description | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| I. Raw Material Preparation | Washing, drying (50 °C, 20 h), grinding, sieving (60 mesh) | Obtained dandelion powder |

| II. Medium Preparation | Powder + distilled water (1:20 w/v), wetting (10 min), pasteurization (90 °C, 10 min), cooling (20 ± 5 °C) | Fermentation medium |

| III. Fermentation | LAB strains: L. plantarum, L. fermentum, L. rhamnosus, L. casei; inoculum 1 × 108 CFU/mL; addition 1% (v/v) | Temperature: 37 °C; time: 8 h |

| IV. Sterilization and Drying | Heating (90 °C, 10 min), drying (45 °C) | Obtained fermented plant material |

| V. Extraction | 1 g fermented material + water (1:100 w/v), ultrasound-assisted extraction (20 kHz, 30 min), centrifugation (4500× g, 10 min, 4 °C) | Obtained bioferment |

| LAB Strain | LA | Phenolic Acid | DPPH IC50 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mg/g] | [g/L] | [mg/g] | [mg/mL] | |

| L. plantarum | 32.53 ± 3.05 | 0.016 | 17.22 ± 1.39 chlorogenic acid | 0.088 |

| L. fermentum | 53.62 ± 1.00 | 0.027 | - | - |

| L. rhamnosus | 55.53 ± 6.13 | 0.028 | - | - |

| L. casei | 53.36 ± 1.71 | 0.027 | 0.77 ± 0.11 caffeic acid 14.90 ± 2.77 cichoric acid | 0.075 |

| Step | Process Description | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Material Preparation | Whole dandelion plant dried in air, ground, sieved (1 mm), sterilized | Substrate for SSF |

| Inoculum Preparation | Mixed inoculum of S. cerevisiae (CGMCC 2.1190) and L. plantarum (CGMCC 1.12934) | Ratio: 3:7 |

| Fermentation Conditions | Solid-State Fermentation (SSF) | Time: 52 h; Temp: 35 °C; Inoculum: 12%; Moisture: 52% |

| Post-Fermentation Extraction | 1 g fermented material + 35 mL 40% ethanol; water bath (70 °C, 30 min); centrifugation (5000 rpm, 15 min) | Supernatant lyophilized |

| Sample Processing | Lyophilized sample ground (zirconia ball mill, 30 Hz, 1.5 min); 100 mg powder extracted overnight at 4 °C in 1 mL 70% methanol | Filtration: 0.22 μm |

| B/E | AA | TPC | LAe | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mmol Tx/L] | [mg GA/L] | [%] | ||

| B-1/E-1 | 3.21 ± 0.01/1.53 ± 0.01 | 2546.69 ± 0.09/1144.88 ± 1.99 | 50 ± 1/0 | [35] |

| B-2/E-2 | 3.01 ± 0.0/1.32 ± 0.1 | 2439.52 ± 0.1/1112.11 ± 2.13 | 53 ± 1/0 | [35] |

| B-3/E-3 | 3.53 ± 0.01/1.99 ± 0.01 | 2599.43 ± 0.12/1764.01 ± 2.66 | 51 ± 1/0 | [35] |

| B-4/E-4 | 2.41 ± 0.01/1.06 ± 0.01 | 2306.82 ± 0.10/1432.77 ± 3.99 | 59 ± 1/0 | [35] |

| B-5/E-5 | 1.19 ± 0.2/0.91 ± 0.2 | 0.92 ± 0.05/0.61 ± 0.04 | 55 ± 1/0 | [108] |

| Target | Goal | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction in CO2 emissions | −55% compared to 1990 levels | 2030 |

| Material circularity rate in the EU | 24% (up from current 12.2%) | 2030 |

| Recycling of cosmetic packaging | 100% recyclable packaging | 2030 |

| Elimination of microplastics in rinse-off cosmetics | Complete elimination | 2027 |

| Elimination of microplastics in leave-on cosmetics | Complete elimination | 2029 |

| EU climate neutrality | Full climate neutrality | 2050 |

| OECD Test | Method Name | Key Parameter | Scope/Application | Regulatory Role | Sustainability & ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 301 | Ready Biodegradability Test | CO2 release, O2 consumption, DOC changes | Chemicals in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, detergents | Rapid evaluation under stringent conditions (REACH, EPA, GHS) | Supports sustainable design; Environmental safety assessment |

| 301A | DOC Die-Away Test | DOC decrease (%) | Water-soluble substances; rapid degradation assessment | REACH, OECD, EPA classification ’readily biodegradable’ | Helps select eco-friendly ingredients; Predicts accumulation in water/soil |

| 301B | CO2 Evolution Test | CO2 released by microorganisms (%) | Organic substances (cosmetics, detergents, pharmaceuticals) | REACH, OECD, EPA criterion ≥ 60% mineralization in 28 days | Supports eco-friendly formulations; Models impact on ecosystems |

| 301C | MITI Test (I) | Oxygen consumption (BOD) | Large-scale chemicals; mainly used in Japan | MITI requirements, OECD | Verifies biodegradability in industrial processes; Risk assessment for large emissions |

| 301D | Closed Bottle Test | Oxygen consumption (BOD) | Water-soluble substances; simple screening | OECD, REACH | Preliminary assessment of cosmetic ingredient biodegradability; Evaluates aquatic ecosystem effects |

| 301E | Modified OECD Screening Test | DOC decrease (%) | Soluble substances during design phase | OECD, REACH | Verification during product design; Assesses persistence in environment |

| 301F | Manometric Respirometry Test | O2 consumption (mg O2/g substance) | Soluble & partially insoluble substances; pressure measurement | OECD, REACH | Selection of low-persistence ingredients; Risk assessment for aerobic degradation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kucharska, E. Recent Progress in Fermentation of Asteraceae Botanicals: Sustainable Approaches to Functional Cosmetic Ingredients. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010283

Kucharska E. Recent Progress in Fermentation of Asteraceae Botanicals: Sustainable Approaches to Functional Cosmetic Ingredients. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010283

Chicago/Turabian StyleKucharska, Edyta. 2026. "Recent Progress in Fermentation of Asteraceae Botanicals: Sustainable Approaches to Functional Cosmetic Ingredients" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010283

APA StyleKucharska, E. (2026). Recent Progress in Fermentation of Asteraceae Botanicals: Sustainable Approaches to Functional Cosmetic Ingredients. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010283