Featured Application

This research falls within the scope of safety sciences, specifically contributing to the field of construction safety. The primary focus of this study is to enhance construction workplace safety through the evaluation of individual psychophysiological parameters. These parameters, when thoroughly examined, have the potential to benefit multiple stakeholders in the construction industry, both during and after the hiring and safety training stages. Findings from this study will provide valuable insights into how workplace stressors can impair workers’ near-miss detection capabilities and safety behavior within the construction enterprise.

Abstract

Despite the introduction of preventive safety measures, such as near-miss reporting, to mitigate accidents and minimize fatalities, construction workers are constantly exposed to stressful situations that negatively affect their safety behavior and reporting efficiency. Occupational stress is induced by various factors, with mental stress and auditory stress being common workplace stressors that impact workers on the job site. While previous studies have demonstrated the effect of stressor conditions on workers’ hazard recognition and safety performance, research gaps persist regarding the direct impact of workplace stressors on workers’ stress levels and near-miss recognition performance. This study investigates workers’ near-miss recognition ability through an eye-tracking experiment conducted in a controlled environment under mental and auditory stress conditions. The findings from this study reveal that workplace stressors triggered by mental and auditory stress can adversely affect worker stress levels, safety behavior, and cognitive processing toward near-miss recognition. Visual attention towards near-miss scenarios was reduced by 26% for mental stress conditions and by 46% for auditory stress conditions compared to baseline. The results may potentially open avenues for developing wearable stress prediction and safety intervention models using bio-sensing technology and personalized safety training programs tailored to individuals with low identification abilities.

1. Introduction

Construction workers are consistently exposed to workplace stress and risk-prone environments. Despite ongoing efforts to enhance construction safety, the construction industry remains one of the most perilous sectors globally [1]. Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicate that over 25,000 fatal injuries were reported between 2016 and 2020 [2]. Falls, caught-in/between, struck-by, and electrocution are identified as primary causes of fatalities in the construction sector [3]. Fatalities associated with the Fatal Four alone surpassed 6000 between 2016 and 2020 [3]. The most common causes of incidents recognized by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in the construction industry include falls, struck-by, caught-in/between, and electrocution hazards. Initiative programs like the Construction Focus Four program are pivotal tools that aim to improve hazard recognition to reduce injury and fatality rates [4]. The presence of safety programs and training assists in limiting accidents, injuries, and fatalities but the dynamic nature of the construction workplace is prone to a wide range of safety hazards that must be proactively identified and eliminated to establish a safer workplace for workers. However, the literature review suggests that construction workers tend to overlook significant safety hazards and fail to recognize 50% of work-related safety hazards in the United States construction sector [5]. Similar studies in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Israel reported failure to identify percentages of 33.5% and 57% for safety hazards [6,7,8]. Near-misses are incidents that can act as early warning signs for unidentified safety hazards that expose workers to an elevated risk of incidents and injuries, including life-threatening catastrophes. A near-miss is “an incident where no property was damaged and no personal injury sustained, but where, given a slight shift in time or position, damage and/or injury easily could have occurred” [9]. Therefore, construction near-miss recognition, a precursor to safety hazards, incidents, or injuries, is crucial for improving workplace safety.

A crucial identifier of workplace safety is a reduction in unsafe acts on the job site that are driven by an individual’s safety behavior. Safety behavior is defined as an individual’s actions to sustain and promote health and safety in the workplace [10]. Construction workers typically operate in high-risk and stressful environments for extended periods, impacting their safety behavior and decision-making. Some studies suggest that various workplace stressors in construction can induce stress, leading to accidents and injuries [11]. Similarly, related studies state that task stressors, such as time pressure and mental demands, can adversely affect workers’ cognitive processes and attention distribution [12].

While previous studies have explored the impact of stressors on workers’ safety behavior through hazard identification, the potential effect of workplace stressors, such as mental and auditory stress, on workers’ near-miss recognition performance is rarely investigated using psychophysiological parameters. Therefore, this study evaluates workers’ near-miss recognition performance using an eye-tracking experiment and psychophysiological parameters under different stressor conditions to bridge this gap. Results from this study will provide valuable insights into how workplace stressors can impair workers’ near-miss detection capabilities and safety behavior within the construction enterprise.

2. Related Works

2.1. Near-Miss Recognition and Eye-Tracking Studies in Construction Safety

In recent times, significant strides have been taken by regulating agencies to enhance safety in the construction workplace for all involved entities. Despite these concerted efforts to mitigate construction accidents, statistical data indicate that the construction industry continues to have the highest fatality rates compared to other sectors. In the United States, recent figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics [13] reveal that the number of fatalities exceeds 1000, with over 200,000 non-fatal incidents. Consequently, the construction industry remains a high-risk and accident-prone sector. The significance of near-misses in the construction industry is substantial regarding accident prevention. The likelihood of an accident or incident decreases as near-miss reporting increases, and addressing near-miss events helps reduce the frequency of incidents [14]. Various studies have characterized near-misses as events that had the potential to lead to more severe conditions but did not result in loss or injury [15,16]. OSHA classifies near-misses into two main categories on their “Near-Miss Incident Report Form”: Unsafe Act and Unsafe Condition [17]. Near-miss recognition, reporting, and resolving rely on construction workers’ ability to effectively identify, report, and intervene in a near-miss incident. Due to the reliability of construction workers for effective near-miss recognition, it is vital to study factors that can provide additional information on workers’ cognitive ability to recognize near-miss incidents.

In the field of cognitive sciences, recognition refers to an individual’s ability to distinguish the identity of an object from numerous others undergoing various identity-preserving changes [18]. The robust relationship between cognitive behavior and eye-tracking evidence establishes visual sensing through wearable eye-tracking technology as an effective tool in construction safety. The movement of individuals’ eyes can facilitate a more profound evaluation of their safety behavior and its impact on recognition performance and decision-making. Studies conducted in the past [7,19,20] have explored the relationship between social gazing and visual information processing abilities. The results from these studies provide strong evidence of a correlation between workers gazing behavior and personality. This connection between cognitive processes, eye movement, and personality traits showcases the potential of utilizing wearable eye-tracking technology to better assess safety behavior in the construction industry. Visual sensing through eye-tracking is used as a tool to evaluate workers’ safety behavior and their proficiency in identifying safety hazards on the job site. A study was conducted to examine workers’ visual attention toward safety hazards showed a significant correlation with their personality traits. Findings suggested that workers with low extroversion, high conscientiousness, and high openness scores demonstrated elevated identification performance towards safety hazards [21]. Additionally, the impact of site condition [22], mental state [23], and experience levels [24] have also been investigated to evaluate the correlation between safety behavior and recognition performance using eye-tracking.

Furthermore, in eye-tracking studies, fixation duration (FD), which is a fixation-derived matrix, can characterize individuals’ visual attention variation during visual search [25,26]. Fixation duration is measured in seconds which records the time and duration when eye movement ceases while gazing at the target area. Reduced fixation count that manifests longer fixation duration is prone to be an indicator of a knowledge-driven and less randomized search strategy, producing increased near-miss recognition proficiency to mitigate accidents and reduce property loss [27]. Similarly, during visual search activities, the worker’s adaptation level to the construction environment is crucial [28]. Time to first fixation (TFF) is another fixation-derived metric that can contribute to evaluating a worker’s adaptation level to external situations. Time to first fixation is quantified by the time it takes the observer to look at the area of interest for the first time. Therefore, a shorter time to first fixation results in higher adaptation levels [29].

2.2. Safety Behavior and Big 5 Personality Traits

Being a labor-intensive industry, workers’ safety is important to stakeholders. A crucial aspect of maintaining safety on a worksite is to promote safety behavior as an integral part of the safety culture. Workers practicing recommended safety behavior should comply with safety policies and procedures and safeguard themselves and others from risk-prone activities [30,31]. The majority of accidents and injuries are caused by failure to carry out recommended safety behavior [32]. Even after enforcing optimum safety behavior at a job site, individuals will always be at risk if they encounter unsafe conditions, or they face unsafe acts carried out by themselves or other workers on site. Although unsafe act is the most significant factor, personality is the driving indicator influencing individuals to practice unsafe acts. Personality is defined as “The dynamic organization within the individual of those psychological systems that determine his characteristics, behavior, and thoughts” [33]. In recent years, there have been efforts to conduct quantitative research to establish a relationship between Big Five personality traits and safety outcomes [34,35]. The Big Five personality trait model is one of the most practiced methods to evaluate an individual’s personality spectrum compared to other counterpart methods present in the psychology field of practice.

In 1992, Goldberg named the term “Big Five” personality traits through his study that provided a framework that analyzed personality based on personal characteristics. This framework included descriptive terms and adjectives that described human beings. Goldberg’s Big Five personality model included a set of 100 unipolar trait descriptive adjectives developed through a series of factor analysis studies that included Big Five factors indexed to a 20-item scale with high robustness and internal consistency [36]. In modern times, brief personality inventories have received traction among researchers over longer versions in academia due to time-dependent limitations. The lengthiness of the traditional model requires 10–15 min to complete the survey, which can induce an experimental bias due to a significant load on participants’ time and patience. The 40-item mini-marker inventory of adjectives [37] addressed the limitations of counterpart personality tests and maintained acceptable robustness and time constraints. All participants can complete this test in approximately 5 min with the ability to produce reasonable Big Five factors for small samples [21]. Big Five mini-marker personality model includes Extraversion (Bashful, Quiet, Shy, Withdrawn, Bold, Extraverted, Talkative, Energetic), Agreeableness (Cold, Harsh, Rude, Unsympathetic, Warm, Cooperative, Kind, Sympathetic), Conscientiousness (Careless, Disorganized, Inefficient, Sloppy, Systematic, Organized, Efficient, Practical), Neuroticism (Relaxed, Unenvious, Moody, Envious, Fretful, Jealous, Touchy, Temperamental), and Openness (Creative, Intellectual, Complex, Deep, Imaginative, Philosophical, Uncreative, Unintellectual) as personality classification traits.

2.3. Psychophysiological Parameters and Stress Measurement

The human body responds to any physical, mental, and environmental changes. Psychophysiological sciences are based on the premise that mental process influences the physiological changes in a human body while the body’s physiology influences emotions, feelings, and motivational behavior [38]. The presence of stress activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) through a biological reaction that triggers the human body to release hormones that initiate a fight-or-flight response, this fight-or-flight response is responsible for the activation of SNS [39]. Stress measurement can be conducted using subjective and objective tools, but the most common tool utilized is subjective assessment, which showcases deficiencies in the complex and dynamic nature of the construction industry. Real-time monitoring of the physiological parameters of construction workers can help track changes in psychophysiological responses under different stress conditions through wearable devices or remote biosensors [40]. Historically, workers-driven unsafe acts are one of the major reasons for accidents in the construction industry [41]. In recent years, studies that evaluate human behavior changes and their relationship with occupation accidents have utilized psychophysiological parameters as a bio-measurement factor through modern wearable technology. These bio-measurements include but are not limited to heart rate (HR), skin temperature (ST), heart rate variability (HRV), electrodermal activity (EDA), and electroencephalography (EEG), which are some of the physiological measurements that can indicate changes in human physiology because of changes in external stimuli. Among these, HR, HRV, and EDA are the most commonly utilized parameters that can be collected through non-invasive techniques to assess body response towards changes in stress levels [42,43].

HR is measured by contracts/beats per minute (bpm), which ranges between 60 (below which is bradycardia) and 100 (above which is tachycardia) in adults [44]. The presence of physiological stress influences the SNS, which is a part of the autonomic nervous system (ANS); HR being a cardiovascular measurement is affected due to external stress, making it an effective evaluation indicator [45]. According to a study conducted by [46], higher heart rates have negatively affected safety awareness and productivity. Near-miss recognition, driven by experience, training, and cognitive effort, induces stress that can lead to an increase in heart rate (HR). Monitoring this physiological parameter can provide a valid assessment of stress induction in individuals.

Including heart rate, electrodermal activity (EDA) has been used as a reliable physiological indicator to monitor workers’ internal reactions. Skin moisture levels tend to fluctuate when the human body is exposed to specific events that produce different levels of electrical signals. These variables inform the EDA signal can be used significantly to understand workers’ mental stress levels [47,48]. Considering unsafe acts are one of the reasons for near-misses in the construction industry, workers’ safety behavior and risk perception become a critical step in the safety decision-making process of near-miss recognition. Since physiological signals such as electrodermal activity (EDA) are affected by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which can fluctuate based on risk perception, these fluctuations in EDA signals can be indicative of perceived risk [49]. In several studies, researchers have used EDA as a physiological indicator of stress and emotional responses. EDA was used as an active indicator to evaluate construction workers’ perceived risk of daily construction activity on the site [50]. In another study, results indicate a strong relationship between the EDA signals of participants with self-reported arousal while reading emotional content aloud [51].

2.4. Role of Workplace Stressor on Workers’ Safety Behavior

In a construction workplace, workers are exposed to active and passive factors that can impact individuals’ productivity and safety behavior. Effective hazard mitigation and near-miss identification depend on active hazard recognition and a proactive decision-making process on the construction site. A large amount of internal cognitive resources is consumed by each individual on-site to handle and evaluate external information [52]. A large amount of cognitive load can be manifested in multiple dimensions in terms of mental effort, mental stress, workplace stress, workplace ability, and work performance as described by [53] in a general model. In the construction industry, workplace stress is described as a pattern of reaction caused by a misalignment between employee’s ability to cope with work-related demand stressors [54]. According to a survey by the Chartered Institute of Building [55], 62% of construction personnel at different levels have experienced stress. Workplace stress or work-related demand stressors include but are not limited to long working hours, working conditions, work overload, work pressure, and role ambiguity [56,57,58].

2.4.1. Mental Stress and Safety in Construction

The manifestation of mental fatigue due to mental stress is another aspect of work-related stress that can induce mental fatigue due to individuals’ cognitive abilities being overloaded, leading to lowered performance for safety hazard detection [23]. Workers’ ability to identify, perceive, and process potential risks is a vital skill for maintaining construction safety reduction, and this ability is a critical factor that can affect construction workers’ safety [28]. Previous literature indicated that workers tend to become hypervigilant under stressful situations while searching for potential safety information in the workplace [59]. Potentially, these workers may process safety information in an unstructured way, leading to a search for rapid solutions, ignoring the most viable solution quickly, and failing to consider all alternative measures [60,61]. Based on these findings, stressful working conditions may reduce safety awareness, leading to human errors in risk-related judgments such as hazard detection.

Accordingly, increased human errors contribute to unsafe behavior and reduce safety performance. Research indicates that workplace stress impairs cognitive functions like hazard recognition and risk perception, resulting in poor judgment and erratic decision-making [62]. Therefore, a reduction in attention can occur due to mental stressors on the worksite that can overrun the limited capacity of cognitive resources at the disposal [63]. Furthermore, this disruption can impact workers’ ability to isolate and focus on hazardous situations, making them inefficient in identifying, intervening, and reporting near-misses. As such, unexpected mental stress triggers increased mental demand in workers that can induce excess mental load and make the process of distinguishing important information from secondary information tremendously difficult, eventually leading to decreased situational awareness [64]. Construction workers are subjected to mental stressors due to the dynamic and demanding nature of the construction workplace, which can impact their attention and risk perception [65]. While there has been an effort to evaluate workers’ mental state and hazard recognition ability, and there has been limited empirical research examining the impact of mental stress on workers’ near-miss recognition performance, this study assesses its effect on fatal four near-misses. Understanding the relationship between mental stress and near-miss recognition is crucial for developing improved safety interventions and coping strategies in construction safety. This research aims to address this gap.

2.4.2. Noise and Effect of Auditory Stress on Workers’ Safety Behavior

In the dynamic nature of construction, construction noise is one of the pollutants that occurs most frequently and severely negatively affects workers’ productivity and health [66,67]. Construction noise-induced effects are commonly classified into two categories: auditory and non-auditory. Auditory effects from noise directly impact workers, exposing them to hearing damage like noise-induced hearing loss (HIHL), noise-induced tinnitus (NIT), and, on some occasions, permanent deafness with prolonged exposure and high frequency exceeding 85 dBA thresholds [67]. Non-auditory effects include behavior performance, workplace safety, cognitive processing, information processing impairment, stress, and emotional discomfort. In past research on noise in the construction industry, researchers have focused on hearing loss and its protection, which are the auditory effects of noise [68].

In addition to protective measures, workers’ safety behavior demands high cognitive ability that can be impacted by excessive noise exposure [69]. When the cognitive performance of construction workers is significantly affected by noise emissions, they are exposed to higher safety risks on the job site [70]. Several studies have affiliated increased noise levels with impaired behavioral and cognitive performance [71,72]. Cognitive performance refers to the ability of an individual to perform a series of cognitive processes, such as perception, judgment, retrieval, and decision-making [73]. Two of the most significant effects of noise stress on cognitive performance are disrupting attention and short-term memory [74]. Noise stress can divert the attention focus of an individual on the task at hand, which may lead to poor decision-making and flawed judgment. The study of noise effect on auditory stress and mental workload has been conducted to evaluate the capabilities of encoding and recalling information while performing a task [75]. A prior study argues that a decrease in cognitive resources for tasks is observed if noise increases mental workload [76]. Another study evaluated 27 participants’ hazard identification under different noise exposure conditions to suggest a negative relationship between hazard identification performance and noise exposure [77]. Additionally, research evaluating the effect of construction noise exposure on masonry work productivity using virtual reality also suggests that the mean productivity of participants decreased by 2.33% at high-intensity noise levels (100 dBA) [78].

However, the previous study suggests that noise can influence workers’ cognitive performance and mental workload by reducing their ability to perceive risk for hazard identification. There is a research gap in quantifying the impact of noise or auditory stress on the near-miss recognition performance of construction workers. This research focuses on filling that gap and improving safety through behavior assessment in the construction industry.

2.5. Point of Departure

This study explores workplace stressors’ impact on workers’ stress levels and near-miss recognition performance using psychophysiological responses and visual sensing. Workers are consistently exposed to workplace stressors on the job site that can affect their safety behavior, cognitive abilities, and hazard recognition performance. Previous studies have shown that eye movement and fixation-derived matrices are reliable indicators of workers’ safety performance when evaluated for variability in external factors [22,23,24]. Although previous studies in the field of construction safety have utilized job stressors and external loading factors to explore arousal and stress levels among construction workers, situational awareness, and visual attention to safety hazards [12,78], a limitation in previous studies related to visual sensing experiments is that the majority of research has focused on construction hazards and accidents as areas of interest for evaluating workers’ safety behavior. Little to no effort has been put into near-miss incidents as a viable interest area for empirical assessment of workers’ near-miss recognition.

Thus, the present study explores workers’ Fatal Four near-miss recognition ability under workplace stressor conditions, specifically mental and auditory stress. To achieve this objective, the following steps were conducted:

- Investigating the effect of workplace stressors (mental and auditory) on workers’ stress levels through psychophysiological responses.

- Exploring the influence of stress conditions on workers’ cognitive processing through visual attention and adaptation levels during near-miss recognition.

- Conducting correlation analysis of workers’ personality traits on their near-miss recognition performance under different stress conditions.

This study contributes to understanding workplace stressors’ impact on workers’ stress levels and their ability to recognize near-miss incidents, providing insights that can improve construction site safety.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Participants

A total of 44 healthy adult participants were recruited for this study. All participants were required to complete a demographic and medical history questionnaire. Through the pre-screening process, five participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Similarly, four participants were excluded due to non-satisfactory physiological and fixation data. The remaining 35 participants (30 males) completed the study, with 31 participants between 18 and 25 and four participants between the ages of 26 and 50; 23 participants had between 1 and 5 years of industry experience, and 2 had more than 5 years of experience. Eight participants reported exposure to past injuries out of 35. All procedures in this study were approved by the Louisiana State University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The sample size for this study was determined by prior research conducted in the field of wearable technology, safety behavior, and eye-tracking experiments. The studies that used wearable technologies to collect physiological data showcased a sample size between 2 and 11 [50,79].

Similarly, non-clinical experimental studies on visual attention and eye-tracking conducted in safety behavior by 28 to 30 participants would provide satisfactory results [21]. Additionally, a prior power analysis was conducted to estimate the sample size for the study design using G*power 3.1.9.4 [80]. With a conservative effect size of f = 0.25, alpha at 0.05, and power at 0.80, the projected total sample size needed with respective effect size is approximately N = 28.

3.2. Data Collection Tools

Experimental data collection was conducted using two wearable devices and one visual sensing device that have been previously used and validated. Before conducting data accusation for the experiment, a pilot study was conducted to assess the feasibility and dependency of using the devices listed below.

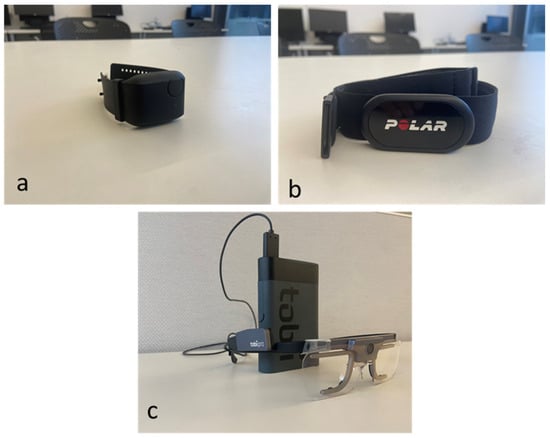

3.2.1. E4 Empathic Wristwatch

Monitoring individuals’ physiological parameters related to the sympathetic nervous system, such as electrodermal activity (EDA), has the potential to evaluate risk perception in near-miss events. In this study, the E4 Empathic Wristwatch is an off-the-shelf wristband type sensor manufactured by Empatica Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA (Figure 1a), which was used to collect EDA data of participants while performing near-miss recognition eye-tracking activity under different stress conditions. EDA electrodes under the snaps were on the wrist’s inside and aligned with the participant’s third (ring) finger. This wearable sensor records EDA data at a sampling rate of 4 Hz.

Figure 1.

Data collection instruments: (a) E4 Empathic Wristband(manufactured by Empatica Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA), (b) Polar H10 Heart Rate Monitor (manufactured by Polar Electro, Inc., Kempele, Finland), and (c) Tobii Pro Glasses 2 (manufactured by Tobii AB Company, Danderyd Municipality, Sweden).

3.2.2. Polar H10 Heart Rate Monitor

Although the E4 wristband sensor is equipped with heart rate data instrumentation, an independent heart rate sensor was selected for HR data collection to ensure the consistency of data processing. The Polar H10 heart rate sensor manufactured by Polar Electro, Inc., Kempele, Finland (Figure 1b) is a wearable heart rate device with a data collecting frequency of 1 Hz. To monitor heart rate, the polar H10 heart rate sensor has been one of the high-precision and accurate instruments used in qualitative studies [81]. This wearable sensor is positioned at the chest level right at the end of the sternum bone, making sure the sensors touch the skin of the chest to record the heart rate in real time.

3.2.3. Tobii Pro Glasses 2

For collecting eye-tracking data during the near-miss recognition experiment, we employed Tobii Glasses 2 (manufactured by Tobii AB Company, Danderyd Municipality, Sweden) to monitor participants’ visual behavior (see Figure 1c). This device has been previously utilized in construction safety research and is effective in quantifying visual sensing. Using wearable eye-tracking technology, we captured and analyzed two-dimensional eye-movement information related to participants’ attention allocation within areas of interest (AOIs). The device features a gaze sampling frequency of 100 Hz with a horizontal camera angle of 82° and a vertical angle of 52°.

3.3. Experiment Design

The study employed a within-subject experimental design to assess the impact of workload stressors and psychophysiological parameters on participants’ near-miss recognition performance. Participants were asked to identify four fatal near-misses from stimuli images under three different stressor conditions on two separate days. This facilitated the removal of carryover effects that may alter the results. Each participant completed a baseline trial (non-stress) first, followed by two stressor condition trials randomized to reduce order effect. The experiment was completed in 65 min, with the first visit taking 45 min and the second taking 20 min. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all the experimental procedures.

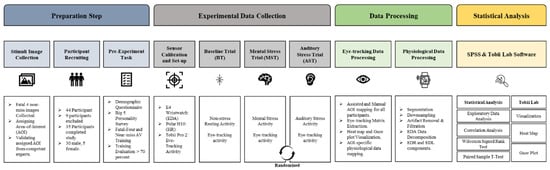

The entire study encompassed four steps:

Step 1: The experiment preparation process commenced with the collection of fatal four near-miss stimuli images from real construction sites and web sources. Stimuli images were carefully selected from a pool and processed to mark designated areas of interest (AOI). To ensure the assigned AOI’s accuracy, all images were validated by competent safety professionals and construction experts. Subsequently, 30 male and 5 female participants were recruited. Before the experiment, participants completed a pre-experiment task that included the completion of the demographic questionnaire, the mini-marker personality survey, and the near-miss and fatal four training video.

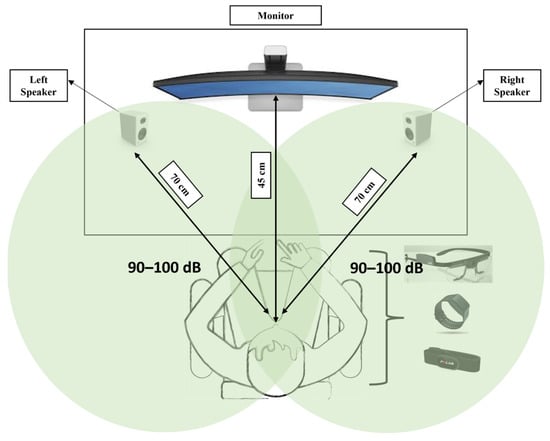

Step 2: The experimental data collection phase began with sensor setup and calibration, during which physiological data and visual sensing data were gathered using specific devices: the E4 wristband for Electrodermal Activity (EDA) data, the H-10 Polar for Heart Rate (HR) data, and the Tobii Pro Glasses 2 (manufactured by Tobii AB Company, Danderyd Municipality, Sweden) for eye tracking metrics. These wearable and visual sensors were connected to mobile devices for data acquisition: The E4 wristwatch was paired with an iPhone XR (128 GB) manufactured by Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA, the H-10 Polar was connected to an iPad Air 2 (128 GB) manufactured by Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA, and the Tobii Pro Glasses 2 were linked to a computer with a Windows operating system (MSI). Calibration for all devices was carefully performed before each experimental trial. After calibrating the sensors, participants were instructed to complete three experimental trials: the Baseline Trial (BT), the Mental Stress Trial (MST), and the Auditory Stress Trial (AST). In the Baseline Trial, participants watched a documentary titled “World Class Trains—The Venice Simplon Orient Express”. This documentary is considered emotionally neutral, and previous research has shown that it does not induce external stress on viewers [82,83,84,85]. Following the documentary, participants performed the near-miss eye-tracking activity. In the Mental Stress Trial, participants were tasked with transforming a four-digit number at their own pace [86]. The participants heard randomized four-digit numbers (e.g., 5341) and responded with the transformation of that number by adding one to each digit of the original number (i.e., 6452). The process continued until the prescribed time elapsed. The rate for this task was one digit per second, which was communicated to participants verbally via the experiment investigator. A series of four-digit numbers were provided to participants at a digit per second rate, and participants had to answer back with a transformed number by adding 1 to each digit at a similar rate. If participants responded incorrect transformed number, they were notified of their mistake. After completing the mental stress activity, participants proceeded to the eye-tracking task, which included different sets of stimuli images for near-miss identification. To induce sensory stress during the Auditory Stress Trial, participants were exposed to high-level construction noise (ranging from 90 to 100 dBA) exceeding 85 dBA. This noise was played from two speakers positioned 70 cm diagonally on either side of the monitor and was randomly sourced from YouTube. The construction noise used as a stressor in this study is a combination of construction equipment noise generated by various equipment (i.e., hammering, hammer drill, and concrete saw). Periodic assessments of noise levels were conducted using the Digital Sound Level Meter Extech 407730 manufactured by Extech Instruments, Burlington, MA, USA. All participants completed the baseline trial first before participating in the MST and AST trials. This allowed benchmarking of the near-miss recognition performance of each participant for stress-induced. Furthermore, MST and AST trials were randomized to remove the order effect.

Step 3: Eye-tracking data processing to extract the eye-tracking matrix for near-miss recognition performance was performed using Tobii Lab software lab version 1.138. Each participant’s physiological data (EDA and HR) underwent several processing stages, which are further detailed in the data-processing section.

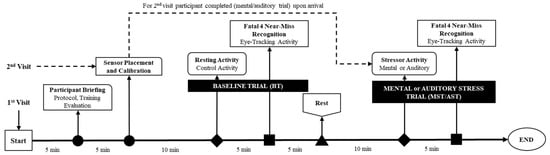

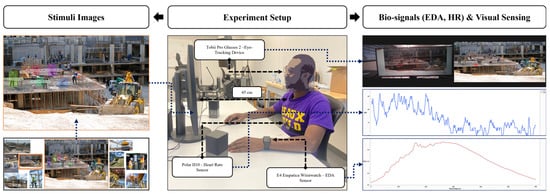

Step 4: Lastly, multiple statistical analyses and visualization techniques, including non-parametric Wilcoxon rank test, paired sampled t-tests, and correlation analysis, were conducted using the data collected from Step 2 and processed through Step 3. These analyses aimed to evaluate the impact of workplace stressors on participants’ psychophysiological parameters and eye-tracking matrices during near-miss recognition. Figure 2 showcases the experimental design of this study.

Figure 2.

Framework of experimental design.

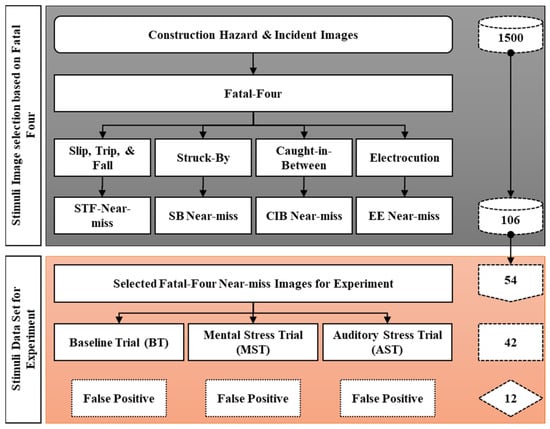

3.4. Stimuli Images, Area-of-Interest (AOI), and Eye-Tracking Activity

Over 1500 images from various construction sites, fabrication shops, and web scrapes were collected to build a robust dataset of fatal four near-misses. These images were carefully screened to meet the study’s requirements for fatal four near-miss recognition, resulting in a shortlist of 106 images with potential fatal four near-misses. AOIs within each image were manually predefined. Experienced safety managers and construction personnel vetted and rectified the assigned AOIs for potentially fatal four near-miss opportunities. A near-miss event is defined as an incident that has a high probability of causing an accident or property loss. Special care was taken to collect images showing four potentially fatal hazards near construction workers. The final dataset comprised 54 images, including 42 images with 48 well-balanced fatal four near-miss AOIs and 12 false positives with no near-misses. Figure 3 illustrates the hierarchical structure of the fatal four near-misses and the image dataset for each trial.

Figure 3.

Fatal four near-misses’ stimuli AOI selection process.

AOIs for this research are categorized in one of the following fatal four areas:

- Slip, Trip, and Fall (falls from the same level, falls from heights, falls from ladders, falls from an elevated scaffolding or other elevated platforms)

- Struck-By (struck-by heavy equipment, vehicles, flying debris, falling objects, machinery, PPE violation, standing under the suspended object, etc.)

- Caught-in-Between (such as being trapped under collapsing structures, equipment, material, caught between two mobilized objects, one stationary and one mobilized object, trench or excavation collapse, pinch point for lower and higher extremities)

- Electrocution (involving improper wiring, overloaded circuits, ungrounded equipment, contact with live circuits without PPE, contact with the energized source, improper use of tools or cords, etc.).

Researchers have examined the optimal size for areas of interest (AOIs) and recommended that AOIs be large enough to encompass all fixation points for the object of interest. They found that smaller AOI sizes are preferable in studies with overlapping fixation distributions, where objects are closely spaced. Conversely, larger AOIs are recommended when there is a greater distance between objects. They proposed an AOI margin of 0.5° of visual angle as optimal for fitting models with overlapping fixations. However, other studies on AOI sizes generally suggest a visual angle margin of 1–1.5° for all experiments [87].

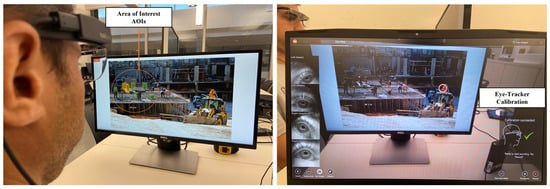

In this study, we employed two-dimensional near-miss scenario images as stimuli for an eye-tracking experiment to accurately assess workers’ recognition performance under stressor conditions. The experiments were conducted in a controlled environment. Experimenting on an actual site was limited due to challenges in data acquisition and the potential introduction of noise that could have compromised the results based on the trial study.

Participants were tasked with completing an eye-tracking activity as part of an experiment to evaluate their near-miss recognition performance. They observed construction site scenes (stimuli) on a monitor positioned 45 cm away and within their line of sight. The objective was to identify the fatal four near-misses in each scene. Each image was displayed for exactly 15 s, followed by a blank screen for an unspecified period. Participants also answered questions regarding their identification of near-misses in each image. This information was used to correlate their fixation data with their awareness and accuracy in identifying near-misses. This eye-tracking evaluation has been utilized in previous studies that investigate two-dimensional near-miss recognition ability [88]. Different stimuli images were used for each trial to remove the AOI familiarization and redundancy. Figure 4 shows participants performing near-miss recognition activity (left image) and the Tobii controller interface for calibration and real-time fixation assessment (right).

Figure 4.

Participant performing eye-tracking activity (Left) and Tobii controller interface for real-time fixation assessment and calibration (Right).

3.5. Experiment Procedure

In this study, participants were asked to complete a pre-experiment task before arriving for the experiment. During their first visit, they received a briefing about the experiment and its protocols. After the briefing, participants signed a consent form and confirmed the completion of the pre-experiment task. They then completed a training evaluation quiz to assess their knowledge of the “fatal four near-misses”, with a required passing rate of 70%. Those who did not meet this threshold had to complete the pre-experiment training before proceeding to the next stage. Once participants were acquainted with the experimental process, they were equipped with wearable biometric sensors and a visual sensing eye-tracker while seated in a relaxed position. After performing sensor calibration and ensuring the consistency of data collection devices, participants were positioned 45 cm from a monitor to begin the experimental trial (Figure 5). Each participant started with a Baseline Trial (BT), which included a non-stress resting activity followed by four fatal near-miss recognition eye-tracking tasks. Post the Baseline Trial, participants were requested to take a 5-min rest. After the rest period, they completed either a Mental Stress Trial (MST) or an Auditory Stress Trial (AST), followed by the near-miss recognition activity. The order of these stressor trials was randomized and counterbalanced to avoid order effects. During the second visit, participants were again subjected to sensor placement and calibration followed by which they completed either the MST or AST according to the pre-defined experimental sequence. The sensors were removed upon completion, and participants were free to leave. Figure 6 illustrates the experiment timeline and schematics [89].

Figure 5.

Experimental setup.

Figure 6.

Experimental procedures.

4. Data Processing and Analysis

4.1. Electrodermal Data Activity (EDA)

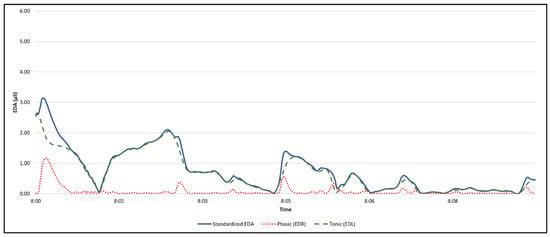

EDA is considered a reliable physiological indicator for detecting changes in sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity that result from active or passive stress conditions. EDA data measure changes in the electrical flow of skin conductance in response to sweat secretion. The decomposition of EDA data in its components can evaluate physiological responses to stress stimuli. EDA data can be split into two components: phasic (i.e., electrodermal response (EDR)) and tonic (i.e., electrodermal level (EDL)). The tonic component (EDL) includes the slow drift of skin conductance and often indicates SNS activity induced by long-term stressors. Meanwhile, phasic (EDR) is considered the fast-changing component of skin conductance, reflecting rapid SNS activity change due to external stressors.

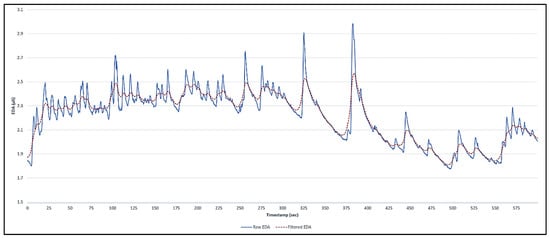

The raw EDA data collected using an E4 emphatic wristband were pre-processed using segmentation and down-sampling procedures. Raw data collected from participants were segmented based on the timestamp for the experiment’s stress loading and eye-tracking phase, and data segmentation was conducted for all three conditions (baseline, mental stress, and auditory stress). After segmentation, EDA data were down-sampled from 4 Hz to 1 Hz using Ledalab (V3.4.9), a MATLAB-based skin conductance data analyzer [90]. Down-sampling of EDA data was necessary to match the sampling frequency of heart rate, which was 1 Hz. Also, the down-sampling process prevents us from overestimating the significance of the statistical analysis. Artifact removal is a common practice while processing physiological data, as EDA data may contain artifacts and noise that can obscure the signals of interest. Therefore, this study applied a low-pass Butterworth filter to the raw EDA data for artifact removal and adaptive smoothening to remove unwanted noise. Ledalab, an open-source tool that provides an artifact removal function, was used to filtrate raw EDA data (Figure 7). For the decomposition of raw EDA data in its phasic (EDR) and tonic (EDL) components, a convex-optimization-based EDA model (cvxEDA) developed by [91] was applied (Figure 8). Before conducting decomposition, the EDA data of each participant were standardized using a z-score to omit individual variations.

Figure 7.

Example of raw EDA data filtration (baseline experiment trial for participant B24).

Figure 8.

Example of EDA data decomposition (EDR and EDL) (baseline experiment trial for participant B24).

4.2. Heart Rate (HR)

Heart rate is another bio-signal measurement used to evaluate physical and psychological activity changes. Compared to EDA activity, literature shows a less significant correlation between stress level and heart rate. These correlation constraints occur because changes in heart rate measurements are due to both sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, which are part of the autonomous nervous system. However, unlike the sympathetic system, which activates the flight or fight responses under stress, the parasympathetic system depicts the human body’s natural activity after exposure to stress. Although EDA is widely used as a physiological indicator to measure stress as the parasympathetic system less influences it, heart rate can also be a vital indicator of stress. Heart rate data for this study were collected using a Polar H10 heart rate sensor. Polar H10 is considered a reliable device by researchers as it is specifically designed to measure the cardiac output activity of the human body. Heart rate data were collected for each participant at a 1 Hz frequency using a chest strap device installed at the base of the sternum. Data were transferred to Polar Beat software version 3.2.0 in real time for further evaluation. Like EDA data, segmentation was conducted for heart rate data. Individual heart rate data were divided into stressor activity and eye-tracking activity for each experiment trial. About 210 individual data sets were provided for three experimental conditions, with two activities for each condition.

4.3. Eye-Tracking Matrix (ET)

To assess participants’ near-miss recognition performance, eye-tracking matrices were extracted for each of the four pre-defined fatal AOIs. Visual sensing data were processed using Tobii Pro Lab version 1.142.1, which offers a comprehensive platform for analyzing eye gaze data with visual and analytical tools. Fixation matrices for each participant were obtained from near-miss recognition activity recordings and mapped onto predefined AOIs using an I-VT fixation filter, with a gaze data classification threshold of 30°/s. This process was applied to all participants across the three experimental conditions. For analysis, eye-tracking matrices, heat maps, and gaze plots were used. The selection of eye-tracking matrices was based on the identification process and cognitive demands being investigated. This study chose two fixation-related matrices to evaluate recognition performance: fixation duration (FD) to measure visual attention and time to first fixation (TFF) to assess adaptation. Figure 9 provides an overview of the experiment’s data collection.

Figure 9.

Experiment data collection flow—near-miss stimuli AOIs, participant performing baseline experiment, and sensing data collected (Left to Right).

4.4. Data Analysis

The effects of workplace stressors (mental stress and auditory stress) on participants’ physiological indicators (EDR and HR) and near-miss recognition performance (fixation duration and time to first fixation) are explored in this section. Additionally, this study investigated the impact of low and high personality levels on participants’ near-miss recognition performance under different stress conditions. Processed EDR, HR, and eye-tracking data were further utilized for analysis.

A within-subject approach was used in which EDR and HR for each participant were decomposed and segmented for each experimental condition. Then, the average EDR and HR were used to conduct statistical analysis to evaluate the overall differences in physiological indicators of stress between baseline trials and workplace stressor trials (mental and auditory).

This study utilized fixation duration (FD) and time to first fixation (TFF) as the eye-tracking matrices to evaluate near-miss recognition performance based on participants’ visual attention and adaptation level. The total fixation duration and time to first fixation associated with each fatal four near-miss AOI were mapped for all participants, providing a data set with 490 data points for each experimental condition. Although participants conducted eye-tracking activity at their own pace, there was a limited window (15 s) to identify near-misses. Therefore, the actual duration for FD and TFF was used, omitting the need to standardize or normalize fixation data. Additionally, participants’ EDR and HR data were mapped for each designated near-miss AOI to investigate near-miss recognition performance under stress conditions.

Personality traits of individual participants were collected using the Big Five personality survey and were assessed for internal consistency using Cronbach alpha reliability analyses. Table 1 shows Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are greater than the widely suggested acceptable value (i.e., coefficient equal to or greater than 0.70). Furthermore, Kendall’s tau correlation analysis examined the relationship and correlation between personality traits, psychophysiological parameters, and eye-tracking matrices for near-miss recognition. Being a non-parametric method, this method is appropriate for non-normal data with less sensitivity to outliers compared to Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients.

Table 1.

Cronbach’s alpha reliability analysis for Big 5 personality traits.

In this study, to identify proper statistical methods for comparing psychophysiological and eye-tracking matrices across baseline versus stressor conditions, exploratory data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 28.0 software. To evaluate the parametric or non-parametric method to be adopted, Shapiro–Wilk’s normality test and the homogeneity of variances were conducted across all data sets. Results from the test indicate that EDR, FD, and TFF data were not normally distributed (p < 0.05 resulted from Shapiro–Wilk’s test), while the HR data provided a normal distribution (p > 0.05 resulted from Shapiro–Wilk’s test). Analysis results from parametric and non-parametric tests conducted on variables are presented in the sections below.

5. Experiment Results

5.1. Effect of Stressors’ Condition on Physiological Responses and Near-Miss Recognition Performance

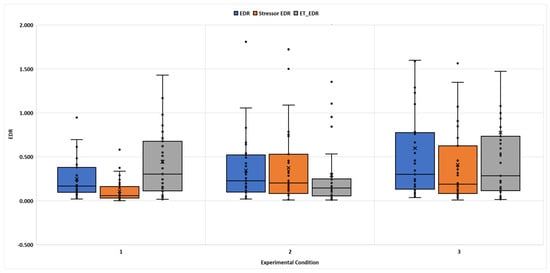

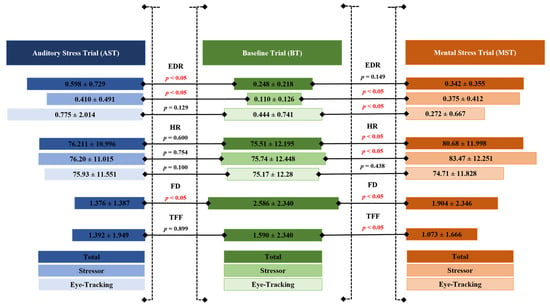

Participants showed variation in their physiological responses across different stress conditions. Each parameter was evaluated to assess the effect of stressors on an individual’s physiological state, including the total trial response (EDRT and HRT) and stressor task response (EDRS and HRS). Table 2 and Figure 10 demonstrate that there were statistically significant differences in participants’ arousal levels (EDRT) between baseline and auditory stress trials with (T-Statistics = −2.932; p-value = 0.003 < 0.05) and mean EDR for auditory stress trial being greater than baseline (mean = MST > BT, 0.598 > 0.248). In contrast, there was no statistically significant difference between baseline and mental stress trials for EDRT. Similarly, the arousal level difference for stressor-specific task response (EDRS) was statistically significant between baseline and mental stress trial (T-Statistics = −3.767; p-value = 0.000 < 0.05) and between baseline and auditory stress trial (T-Statistics = −3.464; p-value = 0.001 < 0.05).

Table 2.

Individual’s segmented EDR measurement across different stressor conditions.

Figure 10.

Box plot (EDR vs. stressor condition): 1—baseline (no stress), 2—mental stress, and 3—auditory stress.

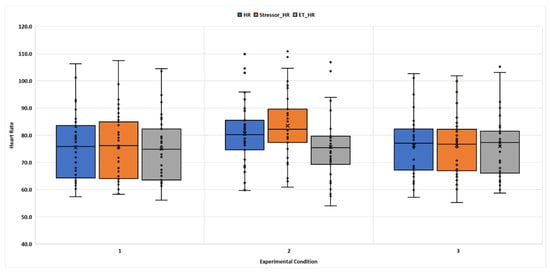

In addition, Table 3 and Figure 11 show a significant statistical difference in participants’ total trial heart rate (HRT) between baseline and mental stress condition (T-value = −3.991; p-value = 0.000 < 0.05) and for stressor task heart rate (HRS) between baseline and mental stress trial (T-value = −5.727; p-value = 0.000 < 0.05). Therefore, results indicate a significant effect of workplace stressors in participant physiological responses (EDR and HR), with mental and auditory stress manifesting stressor load on participants’ stress levels, with mental stress showing a considerably higher effect on individuals.

Table 3.

Individual’s segmented HR measurement across different stressor conditions.

Figure 11.

Box plot (HR vs. stressor condition): 1—baseline (no stress), 2—mental stress, and 3—auditory stress.

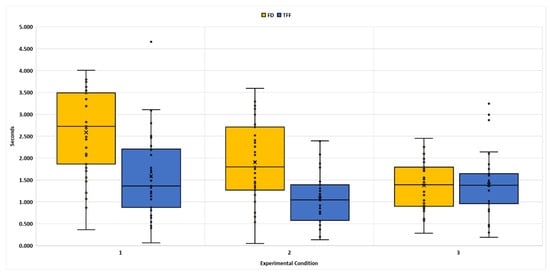

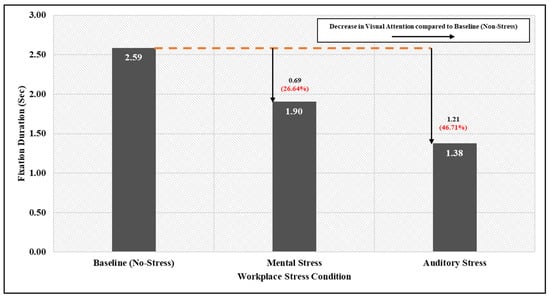

Like physiological responses, statistical analysis was conducted to evaluate whether there is any statistically significant difference in participants’ visual attention (fixation duration) and adaptation level (time to first fixation) for four near-miss AOIs across different stress conditions. Table 4 and Figure 12 indicate that visual attention that is quantified through fixation duration decreased from baseline to mental stress condition (FDBaseline = 2.586, FDMental Stress = 1.904) and from baseline to auditory stress condition (FDBaseline = 2.586, FDAuditory Stress = 1.387). Results from statistical analysis indicate statistically significant differences appear in the fixation duration between baseline and mental stress conditions (T-statistics = −4.061; p-value = 0.000 < 0.05) and between baseline and auditory stress conditions (T-statistics = −7.527; p-value = 0.000 < 0.05).

Table 4.

Variation in fixation duration and time to first fixation across different stressor conditions.

Figure 12.

Box plot (fixation duration and time to first fixation vs. stressor condition): 1—baseline (no stress), 2—mental stress, and 3—auditory stress.

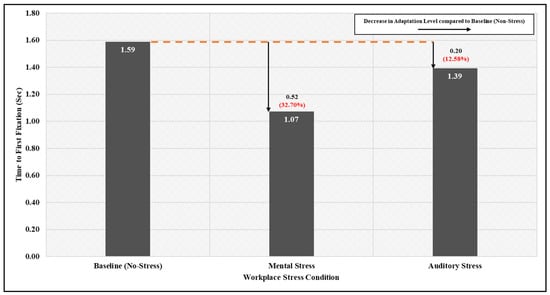

In the case of adaptability in recognizing near-misses, the time to first fixation decreased from baseline to mental stress condition (TFFBaseline = 1.590, TFFMental Stress = 1.073) and from baseline to auditory stress condition (TFFBaseline = 1.590, TFFAuditory Stress = 1.392). Results from the analysis demonstrated no statistically significant difference in time to first fixation between baseline and auditory stress condition (T-statistics = −0.127; p-value = 0.899 > 0.05). However, a statistically significant difference exists for time to first fixation between baseline and mental stress condition (T-statistics = −3.214; p-value = 0.001 < 0.05). These results suggest that workplace stressors (mental and auditory) had a negative effect on participants’ ability to recognize near-misses efficiently. Compared to stressor conditions, mental stress conditions have a larger effect on participants as they decrease visual attention and adaptability levels, showcasing a decreasing trend in fixation duration and time to first fixation. The auditory stress condition also reduced participants’ visual attention (fixation duration) in recognizing near-misses by approximately 47%, but no significant difference was observed in adaptation level (time to first fixation).

5.2. Changes in Physiological Responses During Near-Miss Recognition Tasks in Different Stress Conditions

To further examine the effect of stressor conditions on participants’ physiological responses during near-miss recognition eye-tracking tasks, the analysis considered changes in participants’ EDR and HR parameters across the recognized near-miss AOIs. Specifically, EDR and HR values for each participant were mapped across all fatal four AOIs using timestamp data from wearable sensors and eye-tracking devices. This process was conducted for each participant for each condition and then averaged among all participants for analysis. Table 5 showcases that there is a statistically significant difference in participant EDR between baseline and mental stress condition (T-statistics = −5.418; p-value = 0.000 < 0.05), but no significance between baseline and auditory stress condition (T-statistics = −1.519; p-value = 0.129 < 0.05). Whereas, in the case of HR, results demonstrate no statistically significant difference exists between baseline vs. mental and auditory stress conditions (T-statistics Baseline vs. Mental Stress = 0.776; p-value = 0.438 < 0.05, T-statistics Baseline vs. Auditory Stress = −1.651; p-value = 0.100 < 0.05).

Table 5.

Variation in participants’ EDR and HR measurement across different stressor conditions for AOI-specific eye-tracking activity.

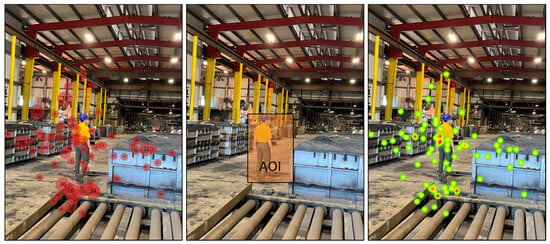

Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 show a gaze plot and heat map of participants under different stressor conditions (baseline, mental, and auditory). Based on the visualization of the heat map, the participant could fixate on near-miss AOI more accurately for baseline conditions (Figure 13). Similarly, the gaze plot shows a higher fixation concentration on and near AOI. This concentration of fixation on gaze plot and allocation of eye movement on heat map gradually reduced from mental (Figure 14) to auditory (Figure 15) stressor condition. Therefore, visualization analysis reinforces the statistical evaluation results that stressor condition negatively impacts participants’ near-miss recognition performance.

Figure 13.

Baseline (non-stress) condition eye-tracking visualization (Left to Right—Gaze Plot, Stimuli, and Heat Map) (Note: Far Left Image numbers represent the search track from lowest to high, far right image color represents fixation duration green being least and red being most).

Figure 14.

Mental stress condition eye-tracking visualization (Left to Right—Gaze Plot, Stimuli, and Heat Map) (Note: Far Left Image numbers represent the search track from lowest to high, far right image color represents fixation duration green being least and red being most).

Figure 15.

Auditory stress condition eye-tracking visualization (Left to Right—Gaze Plot, Stimuli, and Heat Map) (Note: Far Left Image numbers represent the search track from lowest to high, far right image color represents fixation duration green being least and red being most).

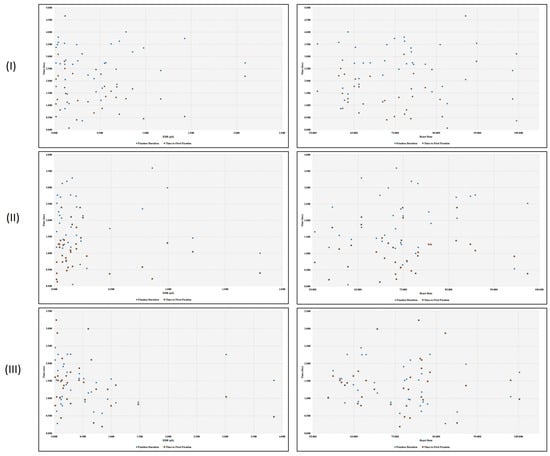

To investigate further the extent of the correlation between workplace stressor conditions and participants’ visual attention and adaptation level to near-miss AOIs, Figure 16 showcases a scatter plot for the baseline and two stressor conditions. As stress intensity changes from baseline to mental stress condition, participants’ fixation duration and time to first fixation are reduced. This can be observed by the increase in convergence and concentration within the scatter plot. A similar trend is observed between baseline and auditory stress condition, whereas for heart rate versus fixation duration and time to first fixation, although there was some convergence within the heart rate range of 65–85 in the scatterplot, there was no significant trend observed as the statistical analysis resulted in non-significant results. Therefore, it can be said that near-miss recognition performance under workplace stress conditions tends to decrease the attention and adaptation level of participants.

Figure 16.

Scatter plot between participants fixation duration, time to first fixation, EDR, and HR across all experiment conditions: (I) baseline (no stress), (II) mental stress, and (III) auditory stress.

5.3. Statistical Relationship and Correlation Analysis: Personality Traits Versus Psychophysiological Parameters and Near-Miss Recognition Performance

The results of Kendall’s tau correlation analysis of personality traits with psychophysiological responses and near-miss recognition performance (visual attention and adaptation level) are presented in Table 6. First, extraversion had a positive correlation only to EDR (correlation coefficient = 0.134, p-value = 0.047 < 0.05), specifically as the score for the extraversion trait in participants increased, their EDR response increased. In comparison, neuroticism showcased a negative correlation with heart rate (correlation coefficient = −0.177, p-value = 0.009 < 0.01). This correlation contradicts the previous finding, as individuals who score high on the neurotic scale tend to have higher heart rates as stress is induced. Second, near-miss recognition performance evaluation based on visual attention and adaptation level only correlated with conscientious and openness personality traits. Conscientiousness positively correlated with time to first fixation (correlation coefficient = 0.147, p-value = 0.030 < 0.05). In contrast, openness is negatively correlated with fixation duration (correlation coefficient = −0.158, p-value = 0.020 < 0.05) and positively correlated with time to first fixation (correlation coefficient = 0.138, p-value = 0.041 < 0.05). Thus, based on statistical correlation analysis, agreeableness is the only personality trait that did not show any relation with psychophysiological parameters and near-miss recognition performance.

Table 6.

Correlation analysis (personality traits vs. psychophysiological and eye-tracking parameters).

6. Discussions

6.1. Workplace Stress and Psychophysiology of Construction Workers

Construction enterprise is considered among the most stressful occupations. Workers in this industry are usually exposed to multiple workplace stressors on site every day, causing a reduction in their productivity [92]. Stress causes cognitive impairment by limiting the availability of decision-making resources at disposal. Therefore, these stressful situations may affect workers’ decision-making toward safety awareness and near-miss recognition. Mental and auditory stress are the two workplace stressors evaluated in this study responsible for altering and influencing participants’ risk-taking behavior [77,85]. Safety awareness and near-miss recognition are important to reduce risk-taking behavior and reduce unsafe acts. The inability to recognize near-misses or lack of understanding may lead to catastrophic accidents or injuries. To quantify the effect of workplace stressors (mental and auditory) on workers’ safety behavior, affecting their near-miss recognition performance, this study utilized psychophysiological parameters (EDR and HR) and eye-tracking matrices. Figure 17 shows a general overview of the results obtained in three experimental conditions.

Figure 17.

Brief overview of the findings.

As shown in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, participants’ psychophysiological responses (EDR and HR) varied under different stress conditions during the experiment trial. The workplace stressor of mental stress impacted participants with unregulated demand, causing an increase in EDR measure (EDRT and EDRS) as compared to baseline condition. Similarly, participants’ heart rates (HRT and HRS) showed increment during mental stress conditions. Such increment and variation in psychophysiological parameters are due to increased demand, a manifestation of induced stress due to workplace stress. As per the definition of stress from the American Institute of Stress, conditions or feelings when perceived demands exceed individual personal and emotional resources are an indication of stress [93].

In the case of auditory stress, a similar trend was observed in participants’ psychophysiological responses. Individuals’ EDR measure (EDRT and EDRS) increased during the auditory stress experiment as a noise stressor was induced, demanding higher cognitive resources. Additionally, as expected, there was an increase in participants’ heart rate measure as the noise was induced in the auditory stress trial since an increase in stress levels due to noise triggers SNS, which increases heart rate [94]. However, no statistical significance was observed regarding the effect of auditory stress on heart rate. Likewise, past research shows inconsistent results in this regard. Some research found an increase in heart rate when exposed to noise [95,96]. Some observed a decrease in heart rate [97,98], while others did not find any significant effect of noise exposure [99]. This inconsistency shows that the impact of noise on heart rate might depend on the type, level, and duration of noise exposure on the participant. This study observed an increasing trend for heart rate measures (HRT and HRS), indicating an increase in SNS activity caused by induced auditory stressors. Thus, increased psychophysiological parameters like HR and EDR from baseline to stressor conditions due to imposed workplace stressors result in increased cognitive demand during near-miss recognition showcased by reduction in FD from baseline to stressor conditions.

6.2. Near-Miss Recognition (Eye-Tracking) Under Stressor Conditions

This study used psychophysiological responses (EDR and HR) and eye-tracking matrices to evaluate the effect of stressor conditions on near-miss recognition performance. As shown in Figure 17, the workplace stressor of mental stress (MST) encountered by participants with excess demand for cognitive processing during an eye-tracking task manifests in the statistically significant difference in EDR measure compared to baseline condition (BT). For auditory stress condition (AST), although there was no statistically significant difference in EDR and HR measures for eye-tracking activity, higher psychophysiological measure demonstrates imposed stress due to stressor condition compared to baseline condition (BT). Similarly, the effect of stressor condition on participants’ near-miss recognition performance evaluated by visual attention (FD) and adaptation level (TFF) showcased a statistically significant difference when compared between baseline condition versus mental and auditory stress condition. As participants encountered stress conditions imposed by stressors, it led to human cognitive failure, resulting in irrational decision-making and reduced fixation duration for near-miss AOIs.

Overall, visual attention (fixation duration) for near-miss recognition was reduced for stressor conditions compared to baseline conditions that can be visualized in Figure 18. There was a 26.64% decrease in fixation duration for mental stress conditions compared to baseline, suggesting that mental stressors induced increased mental workload and decreased cognitive resources for participants, and this reduced their situational awareness to identify near-misses. Similarly, the fixation duration for the auditory stress condition was 46.71% lower than the baseline condition. Higher visual attention reduction during auditory stress suggests that participants’ cognitive recourse was drastically affected by noise stressors compared to mental stressors.

Figure 18.

Stressor condition vs. fixation duration.

In the case of near-miss recognition, participants’ performance based on adaptive level (time to first fixation) towards stressors was reduced during mental and auditory stressor conditions compared to baseline conditions. As provided in Figure 19, there was a 32.70% reduction in time to first fixation for mental stressor condition compared to baseline condition. Participants suffered a 12.58% reduction in time to first fixation for auditory stress condition compared to baseline condition. Time to first fixation is the time spent gazing at the stimuli before first fixation on an area of interest [100]. As the time to first fixation provides an evaluation of the adaptation level of the participants for the variation in stressor conditions, lower time to first fixation represents early recognition of target AOI. Based on the time of the first fixation of participants in this study, individuals could fixate on near-miss AOI better when they were under stress. However, their cognitive process to identify near-misses is reduced, measured by fixation duration. Therefore, stressor conditions diminished visual attention by reducing participants’ near-miss recognition performance and increasing the likelihood of unsafe acts.

Figure 19.

Stressor condition vs. time to first fixation.

6.3. Personality Correlation with Psychophysiological Parameters, and Eye-Tracking Matrices for Near-Miss Recognition

The correlation analysis demonstrates a relationship between extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness with psychophysiological responses and eye-tracking matrices during near-miss recognition. Previous correlation studies indicate a significant relationship exists between personality traits, emotional response, and behavioral states evaluated using physiological data from wearable sensors [101]. Therefore, assessing the correlation of personality traits and psychophysiological parameters during near-miss recognition provides valuable insight into workers’ behavior and cognitive processing. Based on Kendall tau correlation analysis, extraversion (p-value = 0.047 < 0.05) significantly correlated with EDR for all stressor conditions. Individuals with high extraversion personalities who are outgoing, bold, and adventurous reacted actively to stressor conditions, which increased their skin conductance and EDR value. Neuroticism personality trait is depicted as correlated with heart rate (HR) measures across all stressor conditions. A significant correlation (p-value = 0.009 < 0.01) with a negative relationship between neuroticism and heart rate exists during near-miss recognition activity. Individuals who score low on neuroticism traits tend to show calm and relaxed attributes, while individuals under stressor conditions show a significant increase in heart rate measurement due to the activation of the SNS response, triggering their flight or fight response. Conscientiousness and openness showed a correlation between personality traits versus visual attention and adaptation levels of stressor conditions during near-miss recognition. The positive correlation between conscientiousness and the time to first fixation (p-value = 0.03 < 0.05) indicates that more conscientious individuals are likely to fixate on near-miss incidents late compared to other individuals who are less conscientious. This observation is contrary to previous studies’ findings that people with low conscientious traits are usually prone to a higher risk of accidents [102]. This variation in conclusions can result from stressor conditions induced on participants in this study. Openness is the least studied trait concerning safety behavior and near-miss identification.

Moreover, openness showed a contradictory correlation between visual attention and adaptation levels for near-miss recognition performance. There was a significant correlation (p-value = 0.02 < 0.05) and a negative relationship between openness and visual attention (fixation duration). Individuals with high openness scores tend to be curious, intellectual, imaginative, and fixated on the lower duration of near-miss AOIs, whereas a significant correlation (p-value = 0.041 < 0.05) and positive relationship between openness and adaptation level (time to first fixation) during near-miss recognition activity was observed.

7. Conclusions

This research investigated the effect of workplace stressors on workers’ near-miss recognition performance. The results show that inducing mental stress through mental loading tasks and auditory stress through high-frequency noise sensory loading affected participants’ recognition performance and decision-making toward near-miss identification. Such stressors influenced participants’ cognitive process by increasing the requirement for limited cognitive resources and reducing their recognition performance. Participants’ visual attention measured by fixation duration showed statistically significant differences across all stressor conditions, including the significance that there was a reduction in mean fixation duration for mental (26.64%) and auditory (46.71%) stressor conditions compared to baseline (non-stressor) conditions. Meanwhile, adaptation level measurement by time to first fixation was statistically significant only for mental stress conditions, with a reduction of 32.70% compared to the baseline. Therefore, stressor conditions negatively influence participants’ visual attention towards fatal four near-miss incidents and positively affect their adaptability level towards near-miss target areas. Such results show how induced stress from workplace stressors can modulate workers’ recognition performance toward near-miss identification and affect their decision-making process.

The study further analyzed the effect of stressor conditions on near-miss recognition performance using two psychophysiological parameters (EDR–phasic component of EDA and heart rate) and eye-tracking fixation matrices. A combination of psychophysiological responses and fixation-derived matrices provides insights into how workplace stressors can negatively impact workers’ visual attention and decision-making during the near-miss identification process. The experiment presents how mental and auditory stress can influence individuals’ recognition ability and psychophysiological responses. Based on the results, mental stressors have a higher impact on workers’ cognitive processes, increasing their risk-taking behavior. Additionally, correlation analysis was conducted to examine the statistical relationship among personality traits, psychophysiological parameters, and eye-tracking matrices. First, extraversion and neuroticism are statistically correlated to psychophysiological indicators. Conscientiousness and openness are correlated to eye-tracking matrices.

This study contributes to the body of knowledge by providing empirical evidence that workplace stressors like mental and auditory stress can significantly influence workers’ near-miss recognition performance and decision-making process. Safety experts and workforce management can benefit from personality traits measurement as they correlate with response variables. The personality traits that have a positive relationship with psychophysiological response parameters can be used to reallocate workers who can be drastically affected by stress conditions, reducing their exposure to risky behavior.

In terms of practical contributions, this study enhances our understanding of the influence of workplace stressor conditions on workers’ near-miss recognition performance and decision-making process. Furthermore, the reliability of psychophysiological parameters using wearable technologies to detect the presence of stressor conditions on the job site can be used to alert workers for reinforced caution. This can supplement the development of a human-centric stress detection model. Additionally, personality traits having a negative statistical relationship with fixation-derived matrices can be used to create personalized safety training for workers with lower recognition ability.

Despite the findings presented in this study, some limitations remain to be acknowledged. First, using eye-tracking technology, the current study utilized static stimuli to measure near-miss recognition performance.

The stimuli used in this study comprised real-world images depicting fatal four near-miss incidents in construction. Future research could enhance the robustness of experimental evidence by incorporating dynamic near-miss videos and utilizing advanced eye-tracking technology. Additionally, virtual and augmented reality platforms may offer effective alternatives for experimentation. The participant sample in this study was adequate for eye-tracking non-clinical experiments and statistical analysis, comprising individuals from African American, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, and Caucasian ethnic backgrounds. Previous research indicates that Hispanic construction workers might be more susceptible to risk-taking behavior due to a perceived poor safety climate [103]. Future studies should include a more diverse sample and larger participant sizes to better generalize findings across a broader workforce. Moreover, this study exposed participants to a single range of noise levels for auditory stress conditions. Future research should explore various noise exposure ranges to examine their effects on worker recognition performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and C.W.; methodology, S.M. and C.W.; validation, S.M., C.W. and F.A.; formal analysis, S.M.; resources, C.W., F.A. and S.S.B.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, C.W., F.A. and S.S.B.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, C.W. and F.A.; project administration, C.W.; funding acquisition, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2222881.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Louisiana State University (protocol # IRBAM-22-0566 approved on 3 June 2022 and protocol # IRBAM-23-1403 approved on 20 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to sensitive information affiliated with participants’ personality was collected in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shashank Muley was employed by the company Performance Contractors Inc. and author Srikanth Sagar Bangaru was employed by the company Inncircles Technologies Inc.. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Choi, B.; Hwang, S.; Lee, S. What drives construction workers’ acceptance of wearable technologies in the workplace?: Indoor localization and wearable health devices for occupational safety and health. Autom. Constr. 2017, 84, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BLS. Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries. 2021. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/iif/fatal-injuries-tables.htm (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- CPWR. Construction Focus Four. 2022. Available online: https://www.cpwr.com/research/data-center/data-dashboards/construction-focus-four-dashboard/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- OSHA. Outreach Training Program. 2011. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/training/outreach/construction/focus-four (accessed on 15 May 2024).