RTIMS: Real-Time Indoor Monitoring Systems: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Approach

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Real-time system

- -

- Integrated systems containing all main elements: data acquisition, analytics engine, and visualization/dashboard interface

- -

- Systems designed for indoor applications

- -

- Complete systems including hardware, software, and servers

- Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Simulation, theoretical research, and algorithms

- -

- Systems for outdoor environments

- -

- Partial systems (not complete, cannot implement real-time monitoring, or addressing only a specific issue)

- -

- Studies that do not provide information about the components used

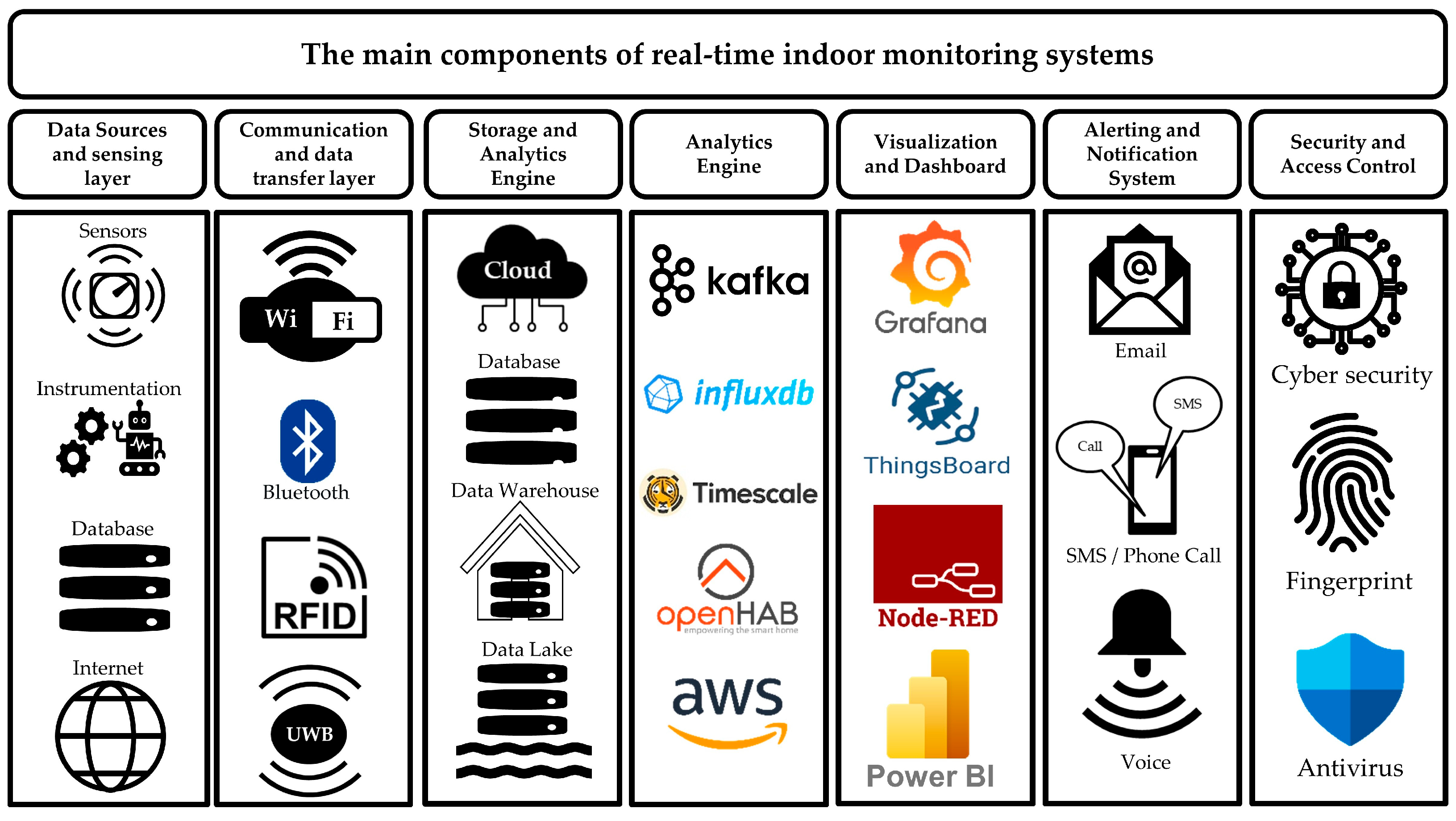

3. RTIMS Technologies

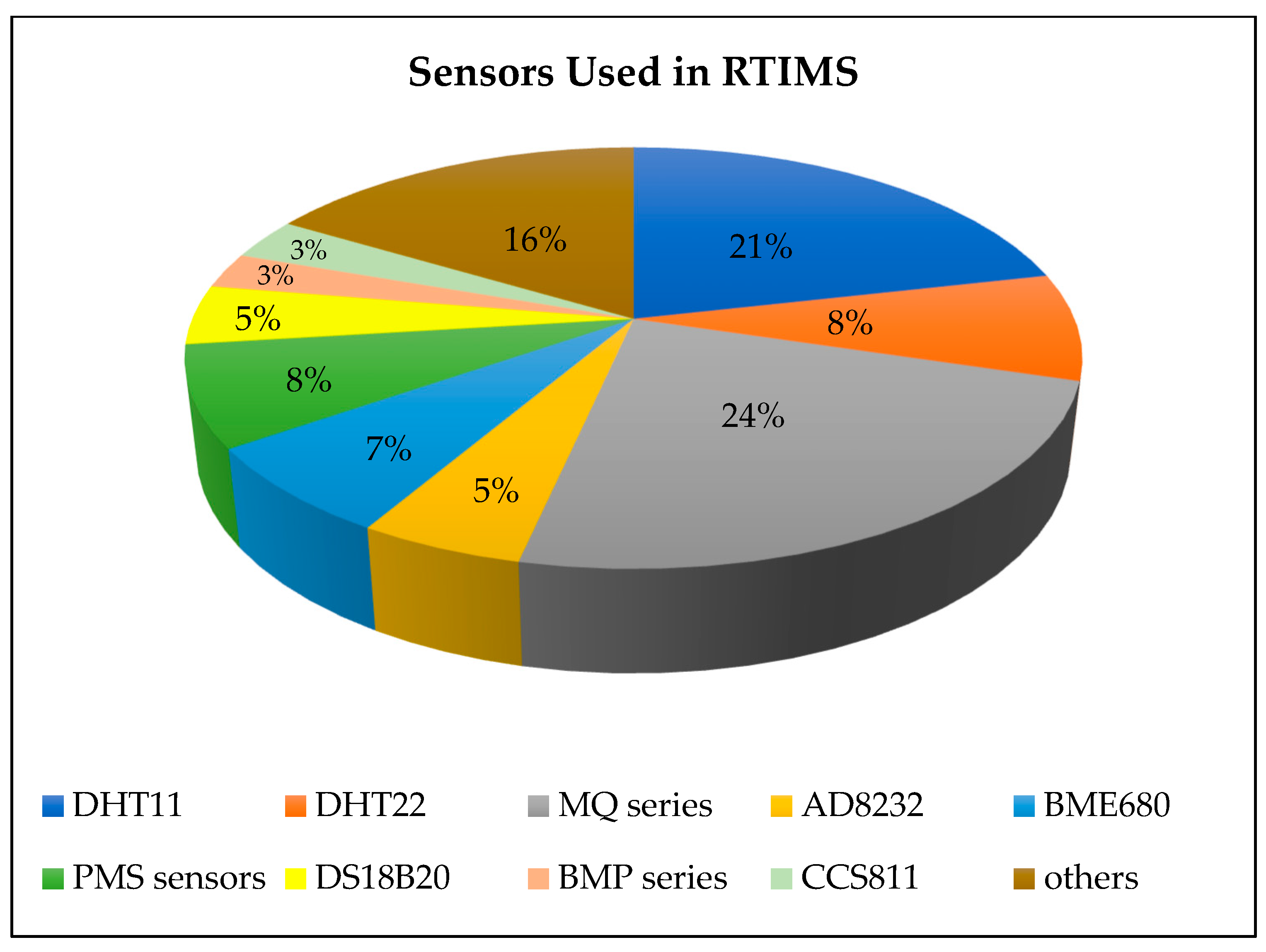

3.1. Data Sources

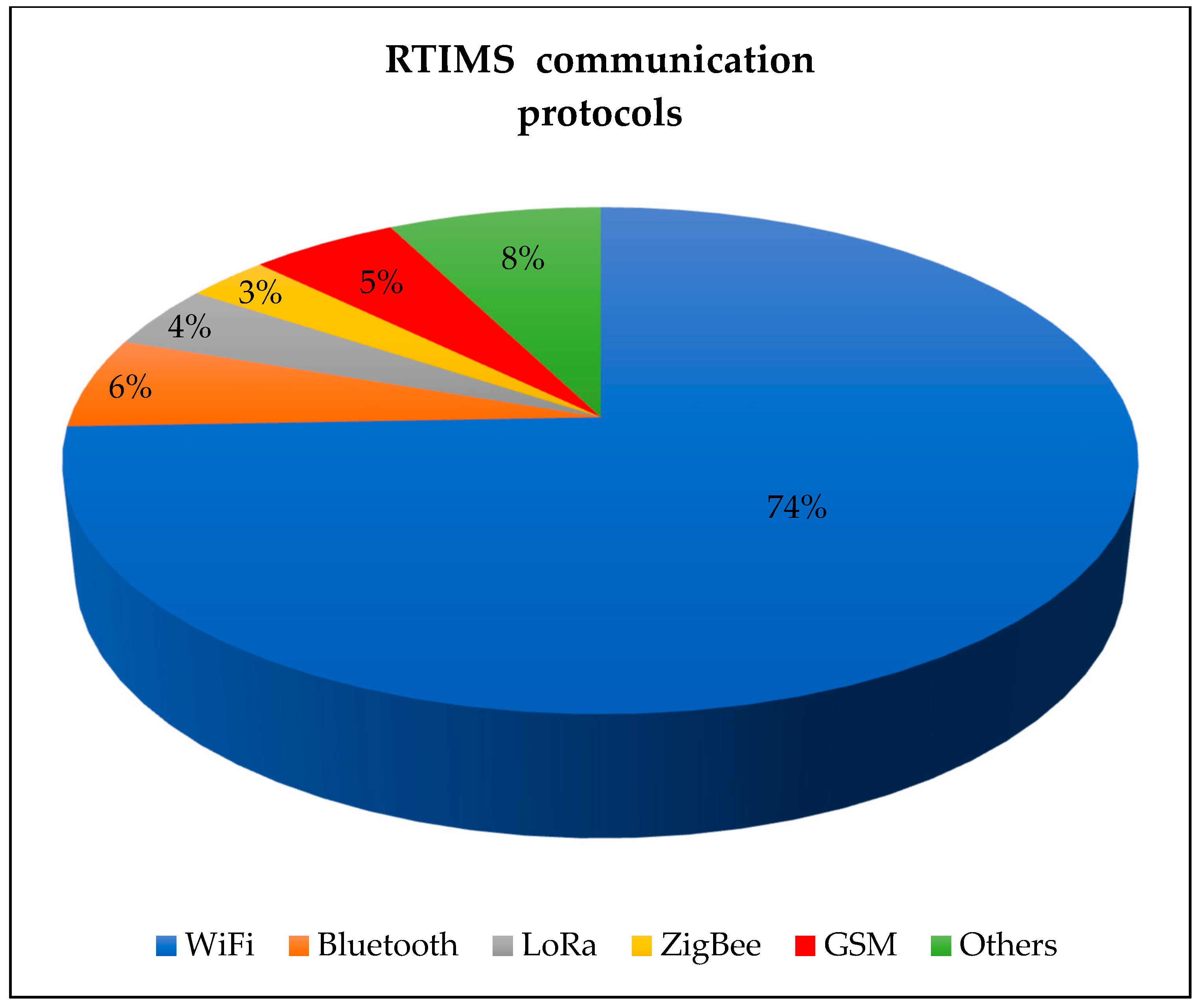

3.2. Communication and Data Transfer Layer

3.3. Storage and Time-Series Database

3.4. Analytics Engine

3.5. Visualization and Dashboard Interface

3.6. Alerting and Notification System

3.6.1. Alerting Strategy

- Events: Any occurrence or change in the normal state that is detected by the monitoring system. These do not necessarily indicate an emergency or require immediate attention. Examples include a door opening or closing, or a scheduled system test.

- Alerts: Notifications regarding specific events that may require attention, but are not necessarily emergencies. Examples include technical issues such as low battery warnings, maintenance reminders, or notifications of system tampering.

- Alarms: High-priority events indicating an emergency or immediate risk, such as fire, or gas leaks.

- High volume of alerts: Excessive alert generation can make it difficult to distinguish critical from non-critical notifications.

- Lack of prioritization: Without a system to prioritize alerts based on their severity, user may treat all alerts equally, leading to desensitization.

- Repetitive alerts: Constant exposure to similar alerts can condition users to ignore them, reducing their responsiveness to new notifications.

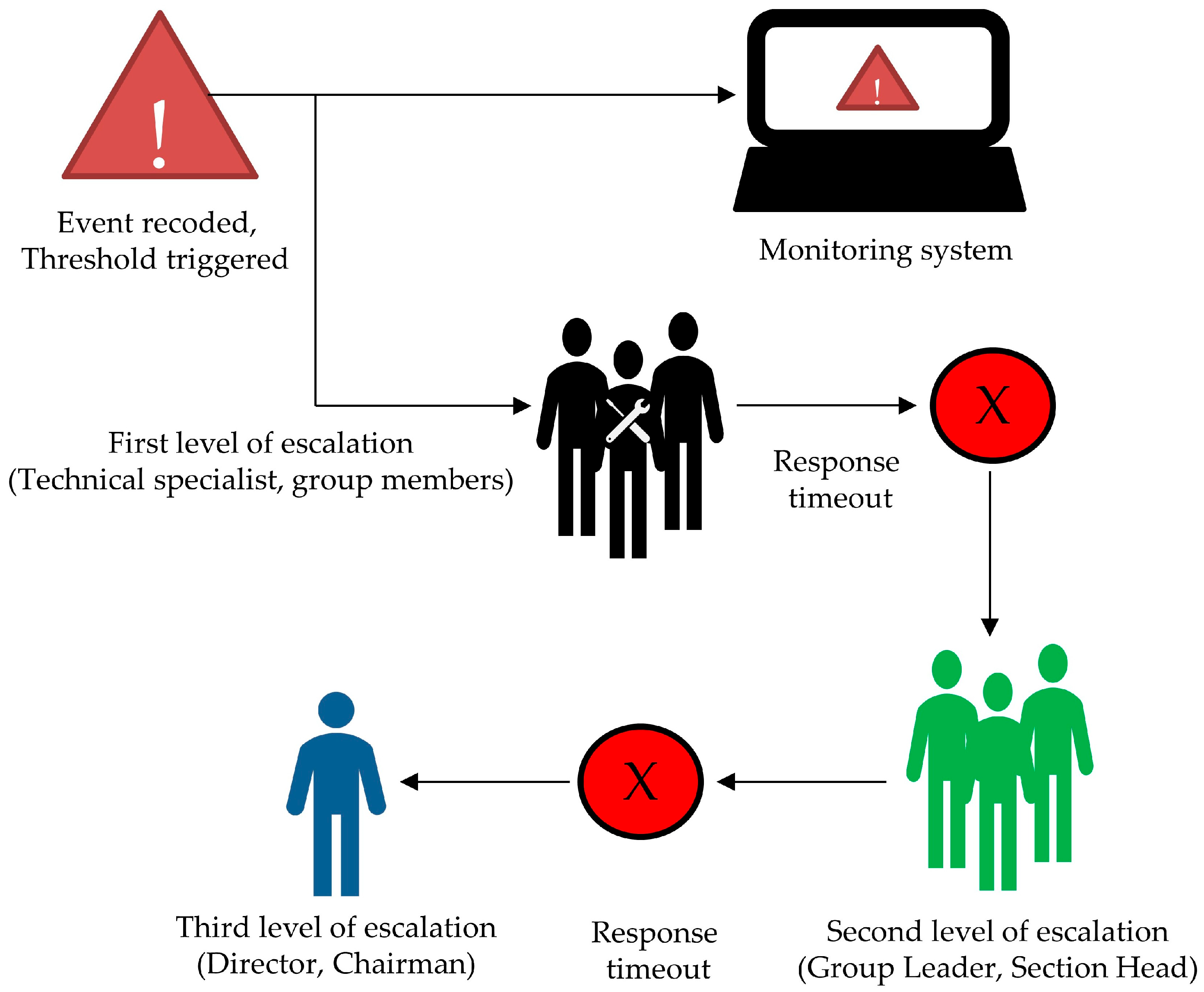

3.6.2. Escalation Policies

3.7. Security and Access Control

4. Benefits of Using RTIMS

4.1. Detecting Errors and Data Anomalies

4.2. Reliable Data Storage

4.3. Data Efficiency

4.4. Data Standardizations

4.5. RTIMS Drawbacks and Implementation Challenges

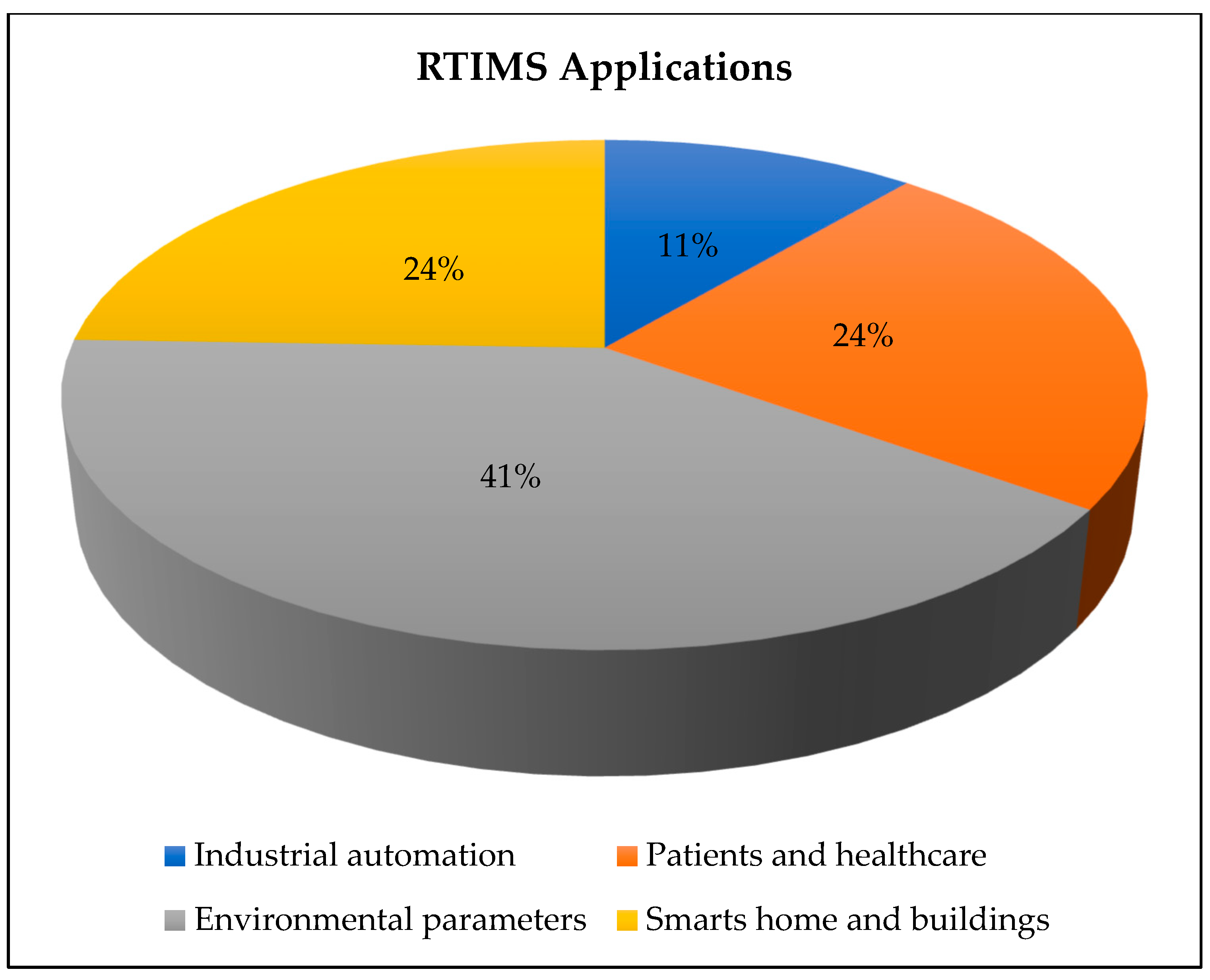

5. RTIMS Application

5.1. RTIMS for Patients and Healthcare

5.2. RTIMS for Industrial Automation

5.3. RTIMS for Environmental Parameters

5.4. RTIMS for Smart Home/Building Monitoring

6. RTIMS Tools Design Criteria

6.1. Scalability

6.2. Ease of Use and Customizability

6.3. Integration Capabilities

7. Results

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saini, J.; Dutta, M.; Marques, G. Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Systems Based on Internet of Things: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, J. Real Time Thermal Environment Monitoring and Interior Design of Intelligent Buildings Based on the Internet of Things. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witczak, D.; Szymoniak, S. Review of Monitoring and Control Systems Based on Internet of Things. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, N.; Rocha, A.D.; Barata, J. Data Management in Industry: Concepts, Systematic Review and Future Directions. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Intelligent Remote Monitoring and Manufacturing System of Production Line Based on Industrial Internet of Things. Comput. Commun. 2020, 150, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, H.; Nasehi, S.; Goudarzi, M. Evaluation of Distributed Stream Processing Frameworks for IoT Applications in Smart Cities. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, A. ESTemd: A Distributed Processing Framework for Environmental Monitoring Based on Apache Kafka Streaming Engine. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Big Data Research, Tokyo, Japan, 27–29 November 2020; pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, S.; Hasselbring, W. Scalable and Reliable Multi-Dimensional Aggregation of Sensor Data Streams. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019; pp. 3512–3517. [Google Scholar]

- Paganelli, A.I.; Mondéjar, A.G.; da Silva, A.C.; Silva-Calpa, G.; Teixeira, M.F.; Carvalho, F.; Raposo, A.; Endler, M. Real-Time Data Analysis in Health Monitoring Systems: A Comprehensive Systematic Literature Review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 127, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad El-Basioni, B.M. A Conceptual Modeling Approach of MQTT for IoT-Based Systems. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2024, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Carvalho, L.I.; Soares, J.; Sofia, R.C. A Performance Analysis of Internet of Things Networking Protocols: Evaluating MQTT, CoAP, OPC UA. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, O.; Gracia Pérez, D.; Brameret, P.-A.; Lacroix, V. Securing IIoT Communications Using OPC UA PubSub and Trusted Platform Modules. J. Syst. Archit. 2023, 134, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.K.; Pedersen, T.B.; Thomsen, C. Scalable Model-Based Management of Correlated Dimensional Time Series in ModelarDB+. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 37th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Chania, Greece, 19–22 April 2021; pp. 1380–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Compressing Time Series Data|TDengine. 2022. Available online: https://docs.tdengine.com/tdengine-reference/sql-manual/manage-data-compression/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- TigerData Documentation|TigerData Architecture for Real-Time Analytics. Available online: https://docs.tigerdata.com/about/latest/whitepaper/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Harby, A.A.; Zulkernine, F. Data Lakehouse: A Survey and Experimental Study. Inf. Syst. 2025, 127, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, A.; Chiavassa, P.; Fissore, V.I.; Servetti, A.; Raviola, E.; Ramírez-Espinosa, G.; Giusto, E.; Montrucchio, B.; Astolfi, A.; Fiori, F. Data Acquisition, Processing, and Aggregation in a Low-Cost IoT System for Indoor Environmental Quality Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamer, A.; Saint-Dizier, C.; Paris, N.; Chazard, E. Data Lake, Data Warehouse, Datamart, and Feature Store: Their Contributions to the Complete Data Reuse Pipeline. JMIR Med. Inform. 2024, 12, e54590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, O.; Pardede, E.; Tomy, S. Cleaning Big Data Streams: A Systematic Literature Review. Technologies 2023, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Li, C.; Fu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wu, T.; Li, G.-P.; Li, B. Machine Learning-Based Real-Time Monitoring System for Smart Connected Worker to Improve Energy Efficiency. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmmod, B.M.; Naser, M.A.; Al-Sudani, A.H.S.; Alsabah, M.; Mohammed, H.J.; Alaskar, H.; Almarshad, F.; Hussain, A.; Abdulhussain, S.H. Patient Monitoring System Based on Internet of Things: A Review and Related Challenges with Open Research Issues. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 132444–132479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A.; Brand, F.; Geppert, J.; Böl, G.-F. Digital Dashboards Visualizing Public Health Data: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 999958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafana: The Open and Composable Observability Platform. Available online: https://grafana.com/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- thingsboard ThingsBoard—Open-Source IoT (Internet of Things) Platform. Available online: https://thingsboard.io/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Power BI—Data Visualization|Microsoft Power Platform. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/power-platform/products/power-bi (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Kibana: Explore, Visualize, Discover Data. Available online: https://www.elastic.co/kibana (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Dash Enterprise|Data App Platform for Python. Available online: https://plotly.com/dash (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Business Intelligence and Analytics Software. Available online: https://www.tableau.com (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Welcome|Superset. Available online: https://superset.apache.org/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Mehrotra, A.; Musolesi, M. Intelligent Notification Systems: A Survey of the State of the Art and Research Challenges 2018. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.10171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, P.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; Clements, C.M.; Celi, L.A.; Herasevich, V.; Hong, Y. Effectiveness of Automated Alerting System Compared to Usual Care for the Management of Sepsis. Npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ultimate Guide to Alarm Management for Operators in the Sludge Management Industry. Available online: https://www.racoman.com/blog/the-ultimate-guide-to-alarm-management-for-operators-in-the-sludge-management-industry (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Gawande, S. Data Monitoring Concepts. iceDQ. 2024. Available online: https://icedq.com/data-monitoring/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- ANSI/TMA-AVS-01 2024 Alarm Validation Scoring Standard—The Monitoring Association. Available online: https://tma.us/standards/tma-avs-01-alarm-validation-standard/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Corporation, O. OnPage: Escalation Policy and Failover. OnPage. 2016. Available online: https://www.onpage.com/onpage-failover-redundancy/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Iqal, Z.M.; Selamat, A.; Krejcar, O. A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Access Control in IoT: Requirements, Technologies, and Evaluation Metrics. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 12636–12654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljahdali, A.O.; Habibullah, A.; Aljohani, H. Efficient and Secure Access Control for IoT-Based Environmental Monitoring. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2023, 13, 11807–11815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, R.; Fersi, G.; Jmaiel, M. Access Control in Internet of Things: A Survey. Comput. Secur. 2023, 135, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Rani, S.; Kumar, V. Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) Enabled Secure and Efficient Data Processing Framework for IoT Networks. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Inf. Secur. IJCNIS 2024, 16, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is Data Monitoring? Importance & Key Techniques|Acceldata. Available online: https://www.acceldata.io/article/what-is-data-monitoring (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Wieder, P.; Nolte, H. Toward Data Lakes as Central Building Blocks for Data Management and Analysis. Front. Big Data 2022, 5, 945720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, N.; Ilayperuma, T.; Jayasinghe, J.; Bukhsh, F.; Daneva, M. The Evolution of Data Storage Architectures: Examining the Secure Value of the Data Lakehouse. J. Data Inf. Manag. 2024, 6, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munbodh, R.; Roth, T.M.; Leonard, K.L.; Court, R.C.; Shukla, U.; Andrea, S.; Gray, M.; Leichtman, G.; Klein, E.E. Real-Time Analysis and Display of Quantitative Measures to Track and Improve Clinical Workflow. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2022, 23, e13610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, G.; Linhares, L.C.M.; Schwartz, K.J.; Burrough, E.R.; de Magalhães, E.S.; Crim, B.; Dubey, P.; Main, R.G.; Gauger, P.; Thurn, M.; et al. Data Standardization Implementation and Applications within and among Diagnostic Laboratories: Integrating and Monitoring Enteric Coronaviruses. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2021, 33, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, L.P.; Parker, C.B.; Cella, D.; Mroczek, D.K.; Lester, B.M. Approaches to Protocol Standardization and Data Harmonization in the ECHO-Wide Cohort Study. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 95, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghari, A.A.; Li, H.; Khan, A.A.; Shoulin, Y.; Karim, S.; Khani, M.A.K. Internet of Things (IoT) Applications Security Trends and Challenges. Discov. Internet Things 2024, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-deep, S.E.; Abohany, A.A.; Sallam, K.M.; El-Mageed, A.A.A. A Comprehensive Survey on Impact of Applying Various Technologies on the Internet of Medical Things. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.; Yan, W.K.; Ma, J.M.; Loh, K.M.; Yu, T.; Low, M.Y.H.; Yar, K.P.; Rehman, H.; Phua, T.C. IoT Devices Deployment Challenges and Studies in Building Management System. Front. Internet Things 2023, 2, 1254160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; Gao, F.; Xu, S.; Wu, X.; Ye, Z. Wearable Health Devices in Health Care: Narrative Systematic Review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e18907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulmalek, S.; Nasir, A.; Jabbar, W.A.; Almuhaya, M.A.M.; Bairagi, A.K.; Khan, M.A.-M.; Kee, S.-H. IoT-Based Healthcare-Monitoring System towards Improving Quality of Life: A Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, F.; Darvishpour, A. Mobile Health Applications in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review of the Reviews. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran MJIRI 2023, 37, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Hertog, E.; Mahdi, A.; Vanderslott, S. A Systematic Review on Patient and Public Attitudes toward Health Monitoring Technologies across Countries. Npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, S.; Alwin, J.; Lekha, J. IoT-Enabled Intelligent Health Care Screen System for Long-Time Screen Users. Eng. Proc. 2024, 82, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.I.; Silva, F.; Pinho, P.; Marques, P.; Abreu, C.; Milheiro, J.; Braga, B.; Queirós, G.; Almeida, R.; Carvalho, N.B. CoViS: A Contactless Health Monitoring System for the Nursing Home. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 20802–20821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Pantha, T.; Arafat, M.A. Design and Development of a Cost-Effective Portable IoT Enabled Multi-Channel Physiological Signal Monitoring System. Biomed. Eng. Adv. 2024, 7, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfandi, H.; Sitanggang, O.S.; Nasution, M.R.A.; Nguyen, H.; Jang, Y.M. Real-Time Patient Indoor Health Monitoring and Location Tracking with Optical Camera Communications on the Internet of Medical Things. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbamalar, T.M.; Devi, A.; Athul, V.G.; Dhinakaran, T. A Real-Time ECG Monitoring System Based on Internet of Things for Diagnosing Cardiac Disorders. In Proceedings of the 2025 3rd International Conference on Inventive Computing and Informatics (ICICI), Bengaluru, India, 4–6 June 2025; pp. 1629–1633. [Google Scholar]

- Yew, H.T.; Ng, M.F.; Ping, S.Z.; Chung, S.K.; Chekima, A.; Dargham, J.A. IoT Based Real-Time Remote Patient Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th IEEE International Colloquium on Signal Processing & Its Applications (CSPA), Langkawi, Malaysia, 28–29 February 2020; pp. 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, A.; Gupta, R.D.; Kabir, M.Z.; Dhar, S. Development of an IoT-Enabled Cost-Effective Asthma Patient Monitoring System: Integrating Health and Indoor Environment Data with Statistical Analysis and Data Visualization. Internet Things 2023, 24, 100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, S.D.; Babić, B.M. Toward the Future—Upgrading Existing Remote Monitoring Concepts to IIoT Concepts. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 11693–11700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guellil, I.; Saâdane, H.; Azouaou, F.; Gueni, B.; Nouvel, D. Arabic Natural Language Processing: An Overview. J. King Saud Univ.—Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 33, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Sun, W.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, W. Cloud–Edge Collaboration for Industrial Internet of Things: Scalable Neurocomputing and Rolling-Horizon Optimization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 19929–19943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Tomar, A.; Hazra, A. Machine Learning Techniques for Industrial Internet of Things: A Survey. In Industry 5.0: Key Technologies and Drivers; Sarkar, I., Hazra, A., Maurya, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 457–477. ISBN 978-3-031-87837-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Oh, D.; Jang, H.; Koo, C.; Hong, T.; Kim, J. Development of a Multi-Node Monitoring System for Analyzing Plant Growth and Indoor Environment Interactions: An Empirical Study on a Plant Factory. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Okby, M.F.R.; Roddelkopf, T.; Huang, J.; Bukhari, M.; Thurow, K. Scalable, Flexible, and Affordable Hybrid IoT-Based Ambient Monitoring Sensor Node with UWB-Based Localization. Sensors 2025, 25, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Lu, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Augmented Reality and Indoor Positioning Based Mobile Production Monitoring System to Support Workers with Human-in-the-Loop. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short-Range Localization via Bluetooth Using Machine Learning Techniques for Industrial Production Monitoring. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2224-2708/12/5/75 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Subhadra, H.; Vakiti, S.R. IoT-Based Coal Mine Safety Monitoring and Alerting System. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Social and Sustainable Innovations in Technology and Engineering (SASI-ITE), Tadepalligudem, India, 23–25 February 2024; pp. 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Pătrășcoiu, N.; Rus, C.; Negru, N. A Solution to Monitor Environmental Parameters in Industrial Areas. In Proceedings of the 2020 21th International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC), Košice, Slovakia, 27–29 October 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, A.H.; Alsabaan, M.; Ibrahem, M.I.; Saraya, M.S.; Elksasy, M.S.M.; Ali-Eldin, A.M.T.; Abdelsalam, M.M. Low-Cost IoT-Based Sensors Dashboard for Monitoring the State of Health of Mobile Harbor Cranes: Hardware and Software Description. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiryasaputra, R.; Huang, C.-Y.; Kristiani, E.; Liu, P.-Y.; Yeh, T.-K.; Yang, C.-T. Review of an Intelligent Indoor Environment Monitoring and Management System for COVID-19 Risk Mitigation. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1022055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Okby, M.F.R.; Roddelkopf, T.; Ewald, H.; Thurow, K. Testing and Integration of Commercial Hydrogen Sensor for Ambient Monitoring Application. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI), Timisoara, Romania, 23–26 May 2023; pp. 000811–000818. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Okby, M.F.R.; Neubert, S.; Roddelkopf, T.; Fleischer, H.; Thurow, K. Evaluating of IAQ-Index and TVOC As Measurements Parameters for IoT-Based Hazardous Gases Detection and Alarming Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 20th Jubilee World Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI), Poprad, Slovakia, 2–5 March 2022; pp. 000291–000298. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhao, L.; Yang, G. Multi-Points Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Based on Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 70479–70492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, A.D.I.A.; Alias, M.R.N.M.; Dzaki, D.R.M.; Din, N.M.; Deros, S.N.M.; Haron, M.H. Cloud-Based IoT Air Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2021 26th IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications (APCC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 11–13 October 2021; pp. 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Freeboard Technology—Home. Available online: https://data.freeboard.tech/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Kim, M.; Kim, T.; Park, S.; Lee, K. An Indoor Multi-Environment Sensor System Based on Intelligent Edge Computing. Electronics 2023, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Gazi, M.S.A. IoT-Cognizant Cloud-Assisted Energy Efficient Embedded System for Indoor Intelligent Lighting, Air Quality Monitoring, and Ventilation. Internet Things 2020, 11, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayat, Y.; El Moussati, A.; Mir, I. Revolutionizing Air Quality Monitoring: IoT-Enabled E-Noses and Low-Power Devices. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, D.; McCullagh, P.; Cleland, I.; Bond, R. Development of an Internet of Things Solution to Monitor and Analyse Indoor Air Quality. Internet Things 2021, 14, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, A.; Gonstał, D.; Maciejewska, M. A Multisensor Device Intended as an IoT Element for Indoor Environment Monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubert, S.; Roddelkopf, T.; Al-Okby, M.F.R.; Junginger, S.; Thurow, K. Flexible IoT Gas Sensor Node for Automated Life Science Environments Using Stationary and Mobile Robots. Sensors 2021, 21, 7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Puryear, N.; Abdelwahed, S.; Zohrabi, N. A Review of IoT-Based Smart City Development and Management. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1462–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, D.; Chen, Z.; Fierro, G.; Gori, V.; Johra, H.; Madsen, H.; Marszal-Pomianowska, A.; O’Neill, Z.; Pradhan, O.; Rovas, D.; et al. Data-Driven Smart Buildings: State-of-the-Art Review; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- Poyyamozhi, M.; Murugesan, B.; Rajamanickam, N.; Shorfuzzaman, M.; Aboelmagd, Y. IoT—A Promising Solution to Energy Management in Smart Buildings: A Systematic Review, Applications, Barriers, and Future Scope. Buildings 2024, 14, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharetha, S.; Soliman, A.M.; Hassanain, M.A.; Alshibani, A.; Ezz, M.S. Assessment of the Challenges Influencing the Adoption of Smart Building Technologies. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 9, 1334005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, N.A.; Abdel-Kader, R.F. Smart Cities after COVID-19: Building a Conceptual Framework through a Multidisciplinary Perspective. Sci. Afr. 2022, 17, e01374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, S.M.H.; Gao, X.; Meng, N.; Agee, P.R.; McCoy, A.P. A Cost-Effective, Scalable, and Portable IoT Data Infrastructure for Indoor Environment Sensing. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, F.I.; Saleh, N.L.; Hashim, F.; Sali, A.; Ali, A.M.; Noor, A.S.M. An IoT-Based Hygiene Monitoring System in the Restroom. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 119348–119361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaheed, S.; Nayak, P.; Rajput, P.S.; Snehit, T.U.; Kiran, Y.S.; Kumar, L. Building IoT-Assisted Indoor Air Quality Pollution Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 22–24 June 2022; pp. 484–489. [Google Scholar]

- Chouragadey, P.; Rathore, B.; Khare, G. Smart Home Automation with MQTT Using ESP32 and Node-RED. In Proceedings of the 2025 Fourth International Conference on Power, Control and Computing Technologies (ICPC2T), Raipur, India, 20–22 January 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, A.; Serôdio, C.; Briga-Sá, A.; Valente, A. Next-Generation Smart Homes: CO2 Monitoring with Matter Protocol to Support Indoor Air Quality. Internet Things 2025, 32, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosti, B.; Jankovic, A.; Goia, F.; Mathisen, H.M.; Cao, G. Design and Performance Analysis of a Low-Cost Monitoring System for Advanced Building Envelopes. Build. Environ. 2025, 269, 112344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, F.; Mirzabeigi, S. Digital Twin-Enabled Building Information Modeling–Internet of Things (BIM-IoT) Framework for Optimizing Indoor Thermal Comfort Using Machine Learning. Buildings 2025, 15, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekren, N.; Sensoy, M.; Akinci, T.C. Smart Buildings Using Web of Things with .NET Core: A Framework for Inter-Device Connectivity and Secure Data Transfer. Information 2025, 16, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, E.; Lopez-Novoa, U.; Sastoque-Pinilla, L.; López-de-Lacalle, L.N. Implementation of a Scalable Platform for Real-Time Monitoring of Machine Tools. Comput. Ind. 2024, 155, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizrakhmanov, R.; Bahrami, M.R.; Platunov, A. Prototype, Method, and Experiment for Evaluating Usability of Smart Home User Interfaces. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2025, 92, 103903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.A.M.; Zaina, L.A.M.; Sampaio, L.N.; Verdi, F.L. On the Evaluation of Usability Design Guidelines for Improving Network Monitoring Tools Interfaces. J. Syst. Softw. 2022, 187, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, S.; Zapata-Madrigal, G.D.; García-Sierra, R.; Cruz Salazar, L.A. Converging IoT Protocols for the Data Integration of Automation Systems in the Electrical Industry. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2022, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.; Villegas-Ch, W.; Govea, J. Modular Middleware for IoT: Scalability, Interoperability and Energy Efficiency in Smart Campus. Front. Commun. Netw. 2025, 6, 1672617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulmozhi, E.; Bhujel, A.; Deb, N.C.; Tamrakar, N.; Kang, M.Y.; Kook, J.; Kang, D.Y.; Seo, E.W.; Kim, H.T. Development and Validation of Low-Cost Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System for Swine Buildings. Sensors 2024, 24, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazen, M.; Nik-Bakht, M.; Moselhi, O. Monitoring Workers on Indoor Construction Sites Using Data Fusion of Real-Time Worker’s Location, Body Orientation, and Productivity State. Autom. Constr. 2024, 160, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafop, N.N.; Abidin, A.Z.; Mohamad, H. IoT-Based Monitoring System for Indoor Air Quality Using Thingsboard. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Applied Electronics and Engineering (ICAEE), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 27 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzaij Al-Okby, M.F.; Roddelkopf, T.; Thurow, K. Low-Cost IoT-Based Portable Sensor Node for Fire and Air Pollution Detection and Alarming. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium (SAS), Naples, Italy, 23–25 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Waworundeng, J.M.S.; Kalalo, M.A.T.; Lokollo, D.P.Y. A Prototype of Indoor Hazard Detection System Using Sensors and IoT. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent System (ICORIS), Manado, Indonesia, 27–28 October 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hapsari, A.A.; Junesco Vresdian, D.; Aldiansyah, M.; Dionova, B.W.; Windari, A.C. Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System with Node.Js and MQTT Application. In Proceedings of the 2020 1st International Conference on Information Technology, Advanced Mechanical and Electrical Engineering (ICITAMEE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 13–14 October 2020; pp. 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Shakunthala, B.S.; Ullas, H.S.; Suresh, M.; Veeraswamy, A. Novel Approach for Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Recent Advances in Science and Engineering Technology (ICRASET), B G NAGARA, India, 23–24 November 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jouda, M.; Wadi, M. IoT with LoRa Architecture for Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing Symposium (IDAP), Malatya, Turkiye, 21–22 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Soon, E.H.K.; Ruan, S.; He, H.; Moghaddassian, M.; Leon-Garcia, A. (POSTER) Cloud Monitoring and Prediction of Indoor LoRa-Based Air Quality Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th Conference on Cloud and Internet of Things (CIoT), Montreal, QC, Canada, 29–31 October 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Vanmathi, C.; Mangayarkarasi, R.; Subalakshmi, R.J. Real Time Weather Monitoring Using Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Information Technology and Engineering (ic-ETITE), Vellore, India, 24–25 February 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rucsandoiu, M.L.; Antonescu, A.M.; Enachescu, M. Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Platform. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Symposium on Signals, Circuits and Systems (ISSCS), Iasi, Romania, 15–16 July 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanasamy, K.; Saon, S.B.; Mahamad, A.K.; Othman, M.B. IoT-Based Air Quality Monitoring System with Air Filter. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Future Technologies for Smart Society (ICFTSS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–8 August 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ligostaev, N.Y.; Kozhemyak, O.A. Development of a Portable Indoor Air Analysis System. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Siberian Conference on Control and Communications (SIBCON), Tomsk, Russian Federation, 17–19 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, S.; Bawa, S.; Sharma, S. IoT Enabled Low-Cost Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System with Botanical Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO), Noida, India, 4–5 June 2020; pp. 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Foysal, F.M.; Sikder, S.; Talha, M.A.; Rimon, M.A.; Parvez, M.S.; Ahmad, S.; Mondal, S.; Hazari, M.R.; Hassan, M. IoT-Based Real-Time Monitoring System for Indoor Air Purification with Gas Leakage Alerts. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques (ICREST), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 11–12 January 2025; pp. 438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Haisiuc, A.C.; Hedes, I.-A.; Firan, D.-O.; Stangaciu, C.; Nimara, S. Bluetooth Sensor Module for Monitoring Indoor Ambient. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI), Timisoara, Romania, 23–26 May 2023; pp. 000449–000454. [Google Scholar]

- Gül, F.; Eroğlu, H. Low-Cost IoT Mesh Network for Real-Time Indoor Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 16–18 December 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, H.; Hazwan, M.N.; Saad, P.S.M.; Harun, Z. The Real-Time Monitoring of Air Quality Using IOT-Based Environment System. In Proceedings of the 2023 19th IEEE International Colloquium on Signal Processing & Its Applications (CSPA), Kedah, Malaysia, 3–4 March 2023; pp. 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Adochiei, F.-C.; Nicolescu, Ş.-T.; Adochiei, I.-R.; Seritan, G.-C.; Enache, B.-A.; Argatu, F.-C.; Costin, D. Electronic System for Real-Time Indoor Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on e-Health and Bioengineering (EHB), Iasi, Romania, 29–30 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fraiwan, L.; Rajab, A.M. Smart Indoor Environment Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 5th Middle East and Africa Conference on Biomedical Engineering (MECBME), Amman, Jordan, 27–29 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, U.; Pawar, A.; Varshney, G.; Yadav, Y.; Sharma, R. Satyajeet IoT Based Smart Monitoring of Environmental Parameters and Air Quality Index. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 8th Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON), Dehradun, India, 11–13 November 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis, I.; Sarri, E.; Tsakiridis, O.; Moutzouris, K.; Triantis, D.; Stavrakas, I. Integrated Open Source Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Platform. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM), Athens, Greece, 20–22 September 2024; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, C. Design of Indoor Environmental Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Symposium on Computer Technology and Information Science (ISCTIS), Xi’an, China, 12–14 July 2024; pp. 302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Guvvala, M.V.; Ch, D. ThingSpeak Based Air Pollution Monitoring System Using Raspberry Pi. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON), Ravet, IN, India, 25–27 August 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Prit, G.; Bharti, M. Smart Indoor Weather Monitoring Framework Using IoT Devices and Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICSC), Noida, India, 5–7 March 2020; pp. 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardo, E.; Polidori, G.; Serpelloni, M. Mobile Autonomous System for Measuring Pollutants in Indoor Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 & IoT (MetroInd4.0 & IoT), Firenze, Italy, 29–31 May 2024; pp. 518–523. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou, G.; Gioulekas, F. Noise Impact Analysis of School Environments Based on the Deployment of IoT Sensor Nodes. Signals 2025, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.; Serôdio, C.; Briga-Sá, A.; Valente, A. Implementation of an Internet of Things Architecture to Monitor Indoor Air Quality: A Case Study During Sleep Periods. Sensors 2025, 25, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietraru, R.N.; Olteanu, A.; Adochiei, I.-R.; Adochiei, F.-C. Reengineering Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Systems to Improve End-User Experience. Sensors 2024, 24, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietraru, R.N.; Nicolae, M.; Mocanu, Ș.; Merezeanu, D.-M. Easy-to-Use MOX-Based VOC Sensors for Efficient Indoor Air Quality Monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Okby, M.F.R.; Junginger, S.; Roddelkopf, T.; Huang, J.; Thurow, K. Ambient Monitoring Portable Sensor Node for Robot-Based Applications. Sensors 2024, 24, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Ulloa, G.; Andrango-Catota, A.; Abad-Alay, M.; Hornos, M.J.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, C. Development and Assessment of an Indoor Air Quality Control IoT-Based System. Electronics 2023, 12, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Al-Ahmed, S.A.; Shakir, M.Z.; Olszewska, J.I. LSTM-Based IoT-Enabled CO2 Steady-State Forecasting for Indoor Air Quality Monitoring. Electronics 2023, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Zepeda, M.J.; Santos-Ruiz, I.; Pérez-Pérez, E.-J.; Navarro-Díaz, A.; Delgado-Aguiñaga, J.-A. Internet-of-Things-Based CO2 Monitoring and Forecasting System for Indoor Air Quality Management. Math. Comput. Appl. 2025, 30, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Shahid, I.; Asif, Z.; Haghighat, F. Indoor Air Quality Assessment Through IoT Sensor Technology: A Montreal–Qatar Case Study. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, L.-M.; Tsai, H.-L.; Tsai, C.-Y. Design and Evaluation of Wireless DYU Air Box for Environment-Monitoring IoT System on Da-Yeh University Campus. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterline, L.M.; Putri, A.A.-Z.R.; Atmaja, P.S.; Dewi, A.L.; Prasetyo, A. Smart Air Monitoring with IoT-Based MQ-2, MQ-7, MQ-8, and MQ-135 Sensors Using NodeMCU ESP32. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 245, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, A.B.; Das, P.; Islam, A.; Fahim, S.M.; Rahman, M.F.; Hasan, E.; Nasim, M.F.T.; Islam, M.M. Real-Time Patient Monitoring System to Reduce Medical Error with the Help of Database System. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Electrical, Computer & Telecommunication Engineering (ICECTE), Rajshahi, Bangladesh, 29–31 December 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, R.; Bharadwaj, S.K.; Saif, S.; Biswas, S.; Bansal, M.; Jain, P.; Cenkeramaddi, L.R. SWAST KHOJ: An IoT-Driven Real-Time Health Monitoring System Prototype. Internet Things 2025, 34, 101796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huria, J.; Hassain, M.M.; Das, B.; Kader, M.A. IoT Based Smart Healthcare System for Real Time Monitoring and Diagnostics in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Innovations in Science, Engineering and Technology (ICISET), Chittagong, Bangladesh, 26–27 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mia, M.M.H.; Mahfuz, N.; Habib, M.R.; Hossain, R. An Internet of Things Application on Continuous Remote Patient Monitoring and Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Bio-Engineering for Smart Technologies (BioSMART), Paris, France, 8–10 December 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-López, Y.; Martínez-Cruz, A.; González, R.Á.; Gálvez, A.M.S. Implementation of an IoT System with a Security Scheme to Predict Indoor CO2 Levels and Mitigate COVID-19 Using Time Series Algorithms. Integration 2025, 103, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zidi, N.M.; Tawfik, M.; Al-Hejri, A.M.; Fathail, I.; Aldhaheri, T.A.; Al-Tashi, Q. Smart System for Real-Time Remote Patient Monitoring Based on Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Computational Methods in Science & Technology (ICCMST), Mohali, India, 17–18 December 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gandah, S.; Chiurazzi, M.; Domina, I.; Dei, N.N.; Spreafico, G.; Scotto di Luzio, F.; Tagliamonte, N.L.; Sanz, S.G.; Fico, G.; Pecchia, L.; et al. An Integrated Sensorized Platform for Environmental Monitoring in Healthcare. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2023, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, I.; Anthony, P.; Astuti, W.; Lie, Z.S.; Iwan Solihin, M. Inpatient Monitoring System: Temperature, Oxygen Saturation, Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, and Infusion Automation Based on ESP 32, IoT, and Mobile Application. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference of Computer and Informatics Engineering (IC2IE), Bali, Indonesia, 12–13 September 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, A.A.; Thomas, A.; Thomas, D.A.; Raji, S.S.; Anu, T.S. IoT-Based Real Time Patient Health and Medical IV Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2025 Emerging Technologies for Intelligent Systems (ETIS), Trivandrum, India, 7–9 February 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Anifah, L. Haryanto Smart Integrated Patient Monitoring System Based Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Information Technology, Information Systems and Electrical Engineering (ICITISEE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 13–14 December 2022; pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jamjoum, M.; Abdelsalam, E.; Siouf, S. Smart Portable Patient Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2022 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–24 February 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Shakir, M.; Arshad, A.; Tariq, M.O.; Sadiq, U.; Shabbir, U. Development of IoT Based Smart System and Data Acquisition for Patient Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 27–28 December 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Akhila, L.; Megha, B.S.; Nikhila, M.S.; Sreelakshmi, B.; Sreehari, K.N. IoT-Enabled Geriatric Health Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2021 Second International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC), Coimbatore, India, 4–6 August 2021; pp. 803–810. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, C.; Varsha, R.; Sakthipriya, V. SIPMS: IoT Based Smart ICU Patient Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Knowledge Discovery in Concurrent Engineering (ICECONF), Chennai, India, 5–7 January 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Farhan, S.; Das, P.; Shabab, S. IoT-Based Health Monitoring System for Real-Time Vital Signs and Hospital Room Conditions Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Quantum Photonics, Artificial Intelligence, and Networking (QPAIN), Rangpur, Bangladesh, 31 July 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ishtiaque, F.; Sadid, S.R.; Kabir, M.S.; Ahalam, S.O.; Wadud, M.S.I. IoT-Based Low-Cost Remote Patient Monitoring and Management System with Deep Learning-Based Arrhythmia and Pneumonia Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computing, Power and Communication Technologies (GUCON), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 24–26 September 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.T.; Shahrizal, R.S.M.; Nadzri, M.N.M.; Yahya, N.; Hisham, S.B. Remote Patient Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 5th International Symposium in Robotics and Manufacturing Automation (ROMA), Malacca, Malaysia, 6–8 August 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Bhadani, V. WanderWatch: LoRaWAN-Based Monitoring System for Wandering Risk Patients. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 17–20 February 2025; pp. 468–472. [Google Scholar]

- Bidilă, T.; Pietraru, R.N.; Ioniţă, A.D.; Olteanu, A. Monitor Indoor Air Quality to Assess the Risk of COVID-19 Transmission. In Proceedings of the 2021 23rd International Conference on Control Systems and Computer Science (CSCS), Bucharest, Romania, 26–28 May 2021; pp. 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, T.; Yu, X. The Vital Signs Monitoring System of The Elderly Based on Cloud Platform. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA), Chongqing, China, 17–19 December 2021; Volume 2, pp. 490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh, C.S.; Kumar, B. Integrated IoT Solution for Continuous Patient Vital Sign Monitoring and Alerting. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th International Conference on Inventive Material Science and Applications (ICIMA), Namakkal, India, 28–30 May 2025; pp. 861–864. [Google Scholar]

- Letchumanan, H.K.; Chew, C.C.; Tay, K.G. IoT-Based Portable Health Monitoring System for Elderly Patients. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Future Technologies for Smart Society (ICFTSS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–8 August 2024; pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, S.; Abinaya, N.; Preetha, K.S.; Velmurugan, T.; Nandakumar, S. An IoT-Driven COVID and Smart Health Check Monitoring System. Open Biomed. Eng. J. 2024, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeethalakshmi, K.; Preethi, U.; Pavithra, S.; Shanmuga Priya, V. Patient Health Monitoring System Using IoT. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 2228–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Mwangi, E.; Kihato, P.K. IoT Based Monitoring System for Epileptic Patients. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-H.; Li, P.-E.; Chen, L.-J.; Liu, Y.-L. Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System for Proactive Control of Respiratory Infectious Diseases: Poster Abstract. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 16–19 November 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 693–694. [Google Scholar]

- Baqer, N.S.; Mohammed, H.A.; Albahri, A.S. Development of a Real-Time Monitoring and Detection Indoor Air Quality System for Intensive Care Unit and Emergency Department. Signa Vitae 2023, 19, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Padwad, D.; Naidu, H.K.; Kokate, P.; Agrawal, P. Smart IoT System for Indoor Plants with Augmented Artificial Lighting. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering & Technology—Signal and Information Processing (ICETET—SIP), Nagpur, India, 28–29 April 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Arigela, A.; Banapuram, C.; Venu, N. Remote Based Home Automation with MQTT: ESP32 Nodes and Node-RED on Raspberry Pi. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Kirtipur, Nepal, 3–5 October 2024; pp. 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Szeidert, I.; Filip, I.; Bordeasu, D.; Vasar, C. Experimental Stand for Testing a Home Automation Solution. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI), Timisoara, Romania, 19–24 May 2025; pp. 000243–000248. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Gupta, H.; Kavitha, P.; Singla, M.K.; Alabdeli, H.; Sharma, B. Smart Living: The Role of IoT in Next Generation Home Automation System. In Proceedings of the 2025 3rd International Conference on Communication, Security, and Artificial Intelligence (ICCSAI), Greater Noida, India, 4–6 April 2025; Volume 3, pp. 2028–2034. [Google Scholar]

- Huamanchahua, D.; Soto-Valqui, L. Development and Implementation of a Home Automation-Type Real Estate Automation Control System-Oriented and Applied to the Elderly Using IoT. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 12th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, USA, 1–4 December 2021; pp. 0069–0073. [Google Scholar]

- Tayus, S.N.; Kamrul Alam Kakon, A.K.M.; Ullah, M. IoT Based Web Controlled Multiple Home Automation and Monitoring with Raspberry Pi. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 27–29 May 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cicceri, G.; Scaffidi, C.; Benomar, Z.; Distefano, S.; Puliafito, A.; Tricomi, G.; Merlino, G. Smart Healthy Intelligent Room: Headcount through Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP), Bologna, Italy, 14–17 September 2020; pp. 320–325. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, F.; Mangoud, M.A. IoT Air Monitoring and Reporting System for Residential Environments. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th IEEE Middle East and North Africa Communications Conference (MENACOMM), Byblos, Lebanon, 20–22 February 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Eliş, B.; Çar, E.; Kasap, N.; Sarı, A.İ.; Rovshenov, A. Development of IoT-Based Smart Home Automation System with Open-Sourced Components. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET), Sydney, Australia, 25–27 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Geck, C.C.; Alsaad, H.; Voelker, C.; Smarsly, K. Personalized Low-Cost Thermal Comfort Monitoring Using IoT Technologies. Indoor Environ. 2024, 1, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Leathey, L.-A.; Anghelita, P.; Constantin, A.-I.; Circiumaru, G.; Chihaia, R.-A. System for Indoor Comfort and Health Monitoring Tested in Office Building Environment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zuo, X.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, Q.; Yin, G. Design of Smart Home Environment Monitoring System Based on STM32. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Symposium on Computer Technology and Information Science (ISCTIS), Chengdu, China, 7–9 July 2023; pp. 823–827. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, N.; Zhou, B. Design and Implementation of Intelligent Home Environment Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA), Xi’an, China, 28–30 March 2025; pp. 1441–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Jian, Z. Stm32-Based Home Environment Monitoring And Model Prediction System. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Industrial IoT, Big Data and Supply Chain (IIoTBDSC), Wuhan, China, 20–22 September 2024; pp. 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chithra, V.; Tharun, D.; Surya, R.; Naveen, B.M.; Karthik, S.L.; Kumar, M.B. Grow Light And Plant Monitoring System For Indoor Gardening. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Power, Energy, Control and Transmission Systems (ICPECTS), Chennai, India, 8–9 October 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, G.; Pachauri, S.; Kumar, A.; Patel, D.; Kumar, A.; Pandey, A. Smart Home Automation with Smart Security System over the Cloud. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 6–8 July 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pietraru, R.N.; Crăciun, R.-A.; Merezeanu, D.-M. Rapid Deployment of Low-Cost Wireless Monitoring Solution for Smart Building. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference Automatics and Informatics (ICAI), Varna, Bulgaria, 10–12 October 2024; pp. 377–380. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, G.; Li, J. Mobile APP-Based Intelligent Monitoring System for the Home Environment. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Symposium on Robotics & Intelligent Manufacturing Technology (ISRIMT), Changzhou, China, 24–26 September 2021; pp. 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, T.; Pang, Z.; Yang, H. Design of Security Monitoring System Based on Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2024 36th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Xi’an, China, 25–27 May 2024; pp. 2661–2666. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, A.; Jesus, V.B.; Gonçalves, C.; Caetano, F.; Silveira, C. Monitoring Indoor Air Quality and Occupancy with an IoT System: Evaluation in a Classroom Environment. In Proceedings of the 2023 18th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Aveiro, Portugal, 20–23 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Chen, V.; Tian, K.; Bigos, I.; Jokic, K.; Haghani, S. HomeBud: A Smart IoT Watering System for Indoor Plants. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–14 January 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kureshi, R.R.; Thakker, D.; Mishra, B.K.; Ahmed, B. Use Case of Building an Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 7th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), New Orleans, LA, USA, 14 June 2021; pp. 747–752. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Maity, S.; Karmakar, R.; Verma, P.; Swayamsiddha, S. Indoor Plant Health Monitoring and Tracking System. In Proceedings of the 2022 OPJU International Technology Conference on Emerging Technologies for Sustainable Development (OTCON), Raigarh, India, 8–10 February 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rashdan, M.; Ahmad Almhaileej, H.Y.; Almutairi, S.A.; Eissa Ashkanani, F.K.; Alhashimi, A.H.; Yousef Madoh, R.H. IoT-Based Home Automation System for Smart Living. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Bio-engineering for Smart Technologies (BioSMART), Paris, France, 14–16 May 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Esfahani, S.; Rollins, P.; Specht, J.P.; Cole, M.; Gardner, J.W. Smart City Battery Operated IoT Based Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE SENSORS, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 25–28 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Alhalabi, D.; Alnakhlani, S.; Fteiha, B.; Zia, H. Enhancing Smart Home Automation: Secure AC Control and Environmental Monitoring with MQTT. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 27–28 December 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, M.; Lee, B. Development of a Portable Monitoring System for Indoor E-Cigarettes Emission. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE SENSORS, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 25–28 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Afroz, R.; Guo, X.; Cheng, C.-W.; Delorme, A.; Duruisseau-Kuntz, R.; Zhao, R. Investigation of Indoor Air Quality in University Residences Using Low-Cost Sensors. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 2023, 3, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Upadhyaya, P.; Chawla, P. Comparative Analysis of IoT-Based Controlled Environment and Uncontrolled Environment Plant Growth Monitoring System for Hydroponic Indoor Vertical Farm. Environ. Res. 2023, 222, 115313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Liu, Y.; Karlsson, M.; Gong, S. A Sensing System Based on Public Cloud to Monitor Indoor Environment of Historic Buildings. Sensors 2021, 21, 5266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfikar, W.B.; Mulyana, E.; Derani, V.A.; Irfan, M.; Alam, C.N. Rule-Based Approach for Air Quality Monitoring System with Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th International Conference on Computing, Engineering and Design (ICCED), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–8 November 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Xu, Z.; Sun, Q. Research and Design of Greenhouse Environment Monitoring System Based on NB-IoT. In Proceedings of the 2021 33rd Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Kunming, China, 22–24 May 2021; pp. 5641–5646. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, N.; Tarigan, S.G.; Mannan, K.A. A Low-Cost IoT System for Monitoring Air Quality in Indoor Working Places. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Information Technology, Information Systems and Electrical Engineering (ICITISEE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 13–14 December 2022; pp. 781–786. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan, S.; Janga, S.R.; Yuktha, S.; Darshini, R.; Monisha, R. Arduino-Based Air Quality Monitoring Robot with ML Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN), Salem, India, 3–4 May 2024; pp. 773–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzaij AI-Okby, M.F.; Neubert, S.; Roddelkopf, T.; Thurow, K. Integration and Testing of Novel MOX Gas Sensors for IoT-Based Indoor Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 21st International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Informatics (CINTI), Budapest, Hungary, 18–20 November 2021; pp. 000173–000180. [Google Scholar]

- Rakib, M.; Haq, S.; Hossain, M.I.; Rahman, T. IoT Based Air Pollution Monitoring & Prediction System. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Innovations in Science, Engineering and Technology (ICISET), Chittagong, Bangladesh, 26–27 February 2022; pp. 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Murdan, A.P.; Jeetun, M.U.-R. Post-Pandemic Air Quality Monitoring System Using Internet of Things (IoT). In Proceedings of the 2023 Third International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Energy (ICAIS), Coimbatore, India, 2–4 February 2023; pp. 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Manjula, B.; Chaitanya, T.; Karedla, P.; Pravallika, V.; Srujana, K. Enhancing Indoor Environment with Smart Ventilation. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN), Salem, India, 14–16 May 2025; pp. 1817–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Fonović, D.; Sirotić, Z.; Tanković, N.; Sovilj, S. Low-Power Wireless IoT System for Indoor Environment Real-Time Monitoring and Alerting. In Proceedings of the 2021 44th International Convention on Information, Communication and Electronic Technology (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 27 September 2021–1 October 2021; pp. 1654–1658. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aloia, M.; Longo, A.; Guadagno, G.; Pulpito, M.; Fornarelli, P.; Laera, P.N.; Manni, D.; Rizzi, M. Low Cost IoT Sensor System for Real-Time Remote Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 & IoT, Roma, Italy, 3–5 June 2020; pp. 576–580. [Google Scholar]

- Catedrilla, G.M.B.; Lerios, J.L.; Asor, J.R.; Cardona, M.V. Development of an Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 15th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management (HNICEM), Coron, Philippines, 19–23 November 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.N.; Islam, M.R.; Faisal, F.; Semantha, F.H.; Siddique, A.H.; Hasan, M. An IoT Based Environment Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems (ICISS), Thoothukudi, India, 3–5 December 2020; pp. 1119–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Fissore, V.I.; Arcamone, G.; Astolfi, A.; Barbaro, A.; Carullo, A.; Chiavassa, P.; Clerico, M.; Fantucci, S.; Fiori, F.; Gallione, D.; et al. Multi-Sensor Device for Traceable Monitoring of Indoor Environmental Quality. Sensors 2024, 24, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barot, V.; Kapadia, V.; Pandya, S. QoS Enabled IoT Based Low Cost Air Quality Monitoring System with Power Consumption Optimization. Cybern. Inf. Technol. 2020, 20, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-López, R.; Vázquez-Carmona, E.V.; Carlos Herrera-Lozada, J.; Miranda, K.; Sandoval-Gutierrez, J. A Proposed Embedded System for Indoor Noise Pollution Monitoring via IoT. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE ANDESCON, Barranquilla, Colombia, 16–19 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, P.H.V.; Hussain, S.M.; Reddy, R.S.; Vinay, R. Iot Based Indoor Environment Monitoring and Controlling with Plant Care. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 5th India Council International Subsections Conference (INDISCON), Chandigarh, India, 22–24 August 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Okby, M.F.R.; Bukhari, M.; Roddelkopf, T.; Thurow, K. Multi-Zone UWB-Based Tracking System for Indoor Environments. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 29th International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems (INES), Palermo, Italy, 11–13 June 2025; pp. 000165–000170. [Google Scholar]

- Nevliudov, I.; Yevsieiev, V.; Maksymova, S.; Demska, N.; Starodubcev, N.; Klymenko, O. Monitoring System Development for Equipment Upgrade for IIoT. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 5th International Conference on Modern Electrical and Energy System (MEES), Kremenchuk, Ukraine, 27–30 September 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaresan, K.; Dhanasekar, R.; Suraj, M.V.; Keshvanth, S.; Gokul Ram, M.; Solomon, A.S. IIOT Based Remote Monitoring and Control of Bottle Filling Process Using PLC and Node-Red. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Communication, Computing and Industry 6.0 (C216), Bangalore, India, 15–16 December 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho, A.P.; Wiratmoko, A.; Nugraha, D.; Markumningsih, S.; Sutiarso, L.; Falah, M.A.F.; Okayasu, T. Development of a Low-Cost Thermal Imaging System for Water Stress Monitoring in Indoor Farming. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amangeldy, B.; Imankulov, T.; Tasmurzayev, N.; Imanbek, B.; Dikhanbayeva, G.; Nurakhov, Y. IoT-Based Unsupervised Learning for Characterizing Laboratory Operational States to Improve Safety and Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Kang, S.; Cho, J.; Jeong, S.; Kim, S.; Sung, Y.; Lee, B.; Kim, G.-H. Implementation of Integrated Smart Construction Monitoring System Based on Point Cloud Data and IoT Technique. Sensors 2025, 25, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udrea, I.; Gheorghe, V.I.; Dogeanu, A.M. Optimizing Greenhouse Design with Miniature Models and IoT (Internet of Things) Technology—A Real-Time Monitoring Approach. Sensors 2024, 24, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Relational Databases | Data Warehouses | Data Lakes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Structured data only | Structured and semi-structured data | Structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data |

| Data Purpose | Operational data | Analytical and reporting data | Raw data and advanced analytics |

| Schema Approach | Schema on write | Schema on write | Schema on- read |

| Scalability | Moderate, vertical scaling | High, horizontal scaling | Very high distributed, and scalable storage |

| Performance | Fast for transactional queries | Optimized for analytical queries | Depending on query engine |

| Storage Cost | Moderate | High | Low |

| Data Volume | MB-GB | Hundreds of GB to many PB. | Hundreds of GB to Exabyte |

| Data Freshness | Real-time or near real-time | Batch, scheduled updates | Batch, streaming data |

| Integration Complexity | Simple | Moderate, requires (extract, transform, load)/(extract, load, transform) ETL/ELT pipelines | High, needs metadata management |

| Best Use Case | Operational monitoring (sensor data, logs) | Business performance analytics and reporting | Centralized raw data repository for advanced analytics and ML |

| Typical Tools/Examples | MySQL, SQL Server, PostgreSQL | Google BigQuery, Snowflake, Azure Synapse, Amazon Redshift | Azure Data Lake, Athena in Amazon S3, Apache Hadoop |

| Tool | Data Source Integration | Visualization Features | Type, Platform | Deployment Mode | Typical Applications | Scalability | Licensing | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grafana | SQL, NoSQL, InfluxDB, JSON APIs, Prometheus | Interactive dashboards, real-time metrics, alerting | Open-source dashboard | On site, Cloud | IoT monitoring, network telemetry, server performance | High | Open Source | [23] |

| ThingsBoard | MQTT, CoAP, HTTP | Customizable dashboards, device telemetry, alerts | IoT platform with dashboard | On site, Cloud | Industrial IoT, data monitoring | High | Open Source/Enterprise | [24] |

| Power BI | SQL, Excel, APIs, Azure, IoT Hub | Advanced charts, key performance indicator (KPIs), AI-driven insights | Business intelligence & analytics | On site, Cloud | Business analytics, IoT dashboards, energy monitoring | High | Commercial (subscription) | [25] |

| Kibana | Elasticsearch, Logstash, Beats | Real-time data visualization, log analytics | Analytics & dashboard | On site, Cloud | Log monitoring, anomaly detection, IoT | High | Open Source | [26] |

| Plotly Dash Enterprise | SQL databases, Excel, Parquet files, APIs | Interactive dashboards, real-time updates | Web-based visualization & dashboard | On site, Cloud | Data visualization, operations control | High | Commercial | [27] |

| Tableau | SQL, CSV, REST APIs | Rich interactive visuals, storyboards | Visualization & analytics | On site, Cloud | Operations dashboards, KPIs tracking | Medium–High | Commercial | [28] |

| Superset (Apache) | SQL databases, APIs | Charts, filters, dashboards | Dashboard | On site, Cloud | Analytics, real-time reporting | Medium | Apache License 2.0 | [29] |

| Data Sources, Sensors | Network, Communication Protocols | Data Storage | Analytical Engine, ML, AI | Visualizations | Notifications Channels | Applications | Reference No., Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGP30, SGP41, SHT41, PMSA003I, MaUWB_ESP32S3 | Wi-Fi, UWB | Microsoft SQL | Cloud | Python-based | Dashboard | Automation | [65], 2025 |

| MD0550, CM1107, DHT22, DS18B20, DRF300 | Wi-Fi, Zigbee | MariaDB | Apache Web Server | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Automation | [64], 2023 |

| PMS5003, MH-Z19C, BME280, LTR-559ALS-01, MICS6814 | Wi-Fi | MySQL, SD card | PHP server | PHP GUI | Dashboard, LCD display | Automation, Environmental | [101], 2024 |

| BLE beacons, accelerometer | Wi-Fi, Bluetooth | Cloud database | Cloud | Revit software, Building Information Modeling (BIM) | Dashboard | Automation | [102], 2024 |

| PowerScout 48 HD, Logitech C922 Pro HD, RealSense D435i, SVPRO Fisheye camera | Modbus Wireless | MongoDB | Web server | Web-based GUI | Dashboard | Automation | [20], 2021 |

| JY90X IMU, LiDAR, UWB, HoloLens2 | Wi-Fi, UWB | Cloud database | Web server | Web-based GUI | Dashboard | Automation | [66], 2024 |

| DHT11, CCS811, GP2Y | Wi-Fi | ThingsBoard platform | Thingsboard Rule Engine | Thingsboard dashboard | Dashboard, Telegram | Environmental | [103], 2024 |

| PMS5003, SHT31, S8 0053 | Zigbee, Modbus | Cloud database | Cloud | Web-based GUI, dashboard | Mobile app. | Environmental | [74], 2021 |

| SGP41, SGP30, SHT40, PMSA00I | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Microsoft SQL | Cloud | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard, Email, SMS | Environmental | [104], 2024 |

| DHT11, MQ2, KY-026, MPU-6050 | Wi-Fi | Cloud based | Blynk cloud based | Mobile app. | Mobile app., LEDs, Speaker | Environmental | [105], 2020 |

| DHT11, MQ135 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | MySQL | Cloud | Web-based Dashboard | Dashboard, Mobile app. | Environmental | [106], 2020 |

| MQ2, MQ9, PMS7003, | Wi-Fi | Web-based | Cloud, ML, AI | Web-based Dashboard | Dashboard | Environmental | [107], 2023 |

| BME680, CCS811 | Wi-Fi | InfluxDB | Amazon Cloud | Freeboard GUI | Dashboard | Environmental | [75], 2021 |

| SPS30, TGS2602, BME680, K30 | LoRa, Wi-Fi | Cloud database | Cloud | MATLAB, web-based Dashboard | Dashboard, Mobile App. | Environmental | [108], 2024 |

| DHT22, SGP30, PMSA003I, MQ9 | LoRa-MQTT | Cloud database | Cloud | Web-based Dashboard | Dashboard | Environmental | [109], 2024 |

| MQ5, DHT11, Water Level Sensor | Bluetooth | SQL database. | Cloud | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard, Mobile app. | Environmental | [110], 2020 |

| Si7006, CCS811, PMS7003 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | MySQL | Node-red | Grafana web-based | Dashboard | Environmental | [111], 2021 |

| DHT11, MQ2, MQ135, MQ4, MQ7 | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak, LCD | Dashboard, Email, SMS | Environmental | [112], 2024 |

| MH-Z19B, TGS2611, PMSDS011, BMP280, SHT30, DS18B20 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Microsoft SQL | Web server | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Environmental | [113], 2022 |

| MQ135, GP2Y1014 | Wi-Fi | Blynk cloud | Blynk cloud | Web-based Dashboard, Mobile app. | Dashboard, Mobile app. | Environmental | [114], 2020 |

| DHT22, PMS5003, MQ6, MQ9 | Wi-Fi | Blynk cloud | Blynk cloud | Web-based Blynk, LCD | Dashboard, mobile app. | Environmental | [115], 2025 |

| BMP180, MQ7, MQ4, HR202 | Bluetooth | Google Firebase Database | Android app. | Python | Mobile app. | Environmental | [116], 2023 |

| MQ135, DHT11 | Bluetooth | Cloud-based | Mobile app | Mobile app | Dashboard, mobile app, Email | Environmental | [117], 2024 |

| MQ135, DHT11, LM35, | Wi-Fi | Blynk cloud | Blynk cloud | Web-based Blynk, LCD | Dashboard, web, mobile app. | Environmental | [118], 2023 |

| DGS-CO968-034, DGS-H2S968-036, DGS-O3968-0424, DGS-NO2968-043, DGS-SO2968-038, RD200M, SPS30, SVM30 | Wi-Fi | Blynk cloud | Blynk cloud | Web-based Blynk, LCD | Dashboard, mobile app. | Environmental | [119], 2020 |

| DHT22, FC22-1, MQ7, SGP30 | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | ThingSpeak platform | Mobile app. | Mobile app. | Environmental | [120], 2020 |

| MQ5, DHT22 | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak | Visual, Email | Environmental | [121], 2021 |

| ENS160, PMS5003, ΒΜΕ280 | Wi-Fi | InfluxDB, SD | Cloud | Grafana web-based | Dashboard, LCD display | Environmental | [122], 2024 |

| DHT11, MQ5, MQ135 | ZigBee | Alibaba Cloud | Alibaba Cloud | WeChat app, OLED | Dashboard, buzzer, mobile app. | Environmental | [123], 2024 |

| DHT11, MQ135 | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak | Dashboard, mobile app. | Environmental | [124], 2023 |

| DHT11, MQ135, BMP180, MG-811 | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak, OLED | Dashboard, mobile app. | Environmental | [125],2020 |

| PMS5003, ENS160, SHTC3 | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak | Dashboard, Email | Environmental | [126], 2024 |

| SEN0232, DHT11, AHT10, | Wi-Fi, LoRa, MQTT | InfluxDB | Node-Red | Node-Red dashboard, Grafana web-based | Dashboard | Environmental | [127], 2025 |

| TGS2600, TGS2602, Cozir-Blink5000, PID-AH2, PMS5003, Grove Multichannel Gas Sensor V2, BH1750, MPL3115A2 | Wi-Fi, MQTT, GSM, Ethernet | microSD, Cloud-based | Cloud-based | Dashboard, mobile app | Dashboard, mobile app | Environmental | [81], 2024 |

| BME680, SGP30, MS5803-05BA | Wi-Fi, Bluetooth | Microsoft SQL | Cloud-based | Dashboard | Dashboard | Environmental, Automation | [82], 2021 |

| SCD30, SHT35, BME680, SGP30, BH1750, BMP388, SEN0376, SEN0321, SEN50135, C930, PMS5003, S-pH-01A, Air Korea | Wi-Fi, MQTT | InfluxDB, Cloud-based | Cloud-based | Grafana | Dashboard | Environmental | [77], 2023 |

| SN-GCJA5, SCD40, | Wi-Fi, MQTT | InfluxDB | Telegraf, InfluxDB Cloud-based | InfluxDB Dashboard | Dashboard | Environmental | [128], 2025 |

| SEN55 | Wi-Fi | ThingsBoard Cloud based | ThingsBoard platform | ThingsBoard Dashboard | Dashboard, mobile app | Environmental | [129], 2024 |

| AGS01DB, AGS10, AGS02MA, SGP30, SEN55, BME680, SGP40, CCS811, ENS160, iAQ-Core | Wi-Fi, MQTT | ThingsBoard Cloud based | ThingsBoard platform | ThingsBoard Dashboard | Dashboard | Environmental | [130], 2024 |

| BME680, ENS160, PGS1004, SGP41, MS5803-05BA | Wi-Fi | Microsoft SQL | Cloud | Web based Dashboard, GUI App. | Dashboard, LCD | Environmental, Automation | [131], 2024 |

| MQ7, MQ135, DHT11, | Wi-Fi | MySQL | Cloud | Web-based Dashboard, Mobile app | Dashboard, mobile app | Environmental | [132], 2023 |

| BME680, SCD30, | Wi-Fi, MQTT | InfluxDB | InfluxDB Cloud-based, Node-Red | Grafana | Dashboard | Environmental | [133], 2023 |

| SHT41, VEML7700, IMP34DT05, SFA30, MICS_VZ_89TE, SEN54, SCD30, 3SP_NO2_5F, 3SP_CO_1000 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | MySQL | Cloud | Web-based Dashboard | Dashboard | Environmental | [17], 2024 |

| MH-Z19D | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak | Dashboard, mobile app | Environmental | [134], 2025 |

| SCD30, SEN54, Grove Multichannel V2, SFA30 | Wi-Fi | MySQL, BlueHost cloud based | Web server | Web based Dashboard | Dashboard | Environmental | [135], 2025 |

| BME680, BH1750, SCD30, PMS7003T | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak | Dashboard | Environmental | [136], 2024 |

| DHT11, MQ135 | Wi-Fi, GSM | Cloud based | Cloud server | Web-based Dashboard, Mobile app | Dashboard, SMS, visual alarm | Environmental | [78], 2020 |

| BME680 | Wi-Fi | MySQL | Web server | Web-based GUI | Dashboard | Environmental | [80], 2021 |

| PM900M, MHZ19C, ZP07, ZE27-O3, ZE07-CO, MiCS- 2714, ZE08CH2O | Wi-Fi, LoRa, MQTT | Cloud based | Cloud server | Web-based Dashboard | Dashboard, mobile app. | Environmental | [79], 2024 |

| MQ2, MQ7, MQ8, MQ135, DHT11 | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak, LCD | Dashboard | Environmental | [137], 2024 |

| MAX30102 | Optical signals, OOK modulation | MariaDB | Nginx and Apache web based | web application | Dashboard | Healthcare | [56], 2024 |

| DHT22, AD8232 ECG, SpO2 | Wi-Fi, GSM | Cloud based | Cloud server | Google Data Studio dashboard, LCD | Dashboard, LCD, SMS | Healthcare | [138], 2022 |

| DS18B20, SpO2, ECG, Max30100 | Wi-Fi, ZigBee, Bluetooth | local server, cloud server | AI based risk level prediction | Local monitoring device, web application | Dashboard, mobile app. | Healthcare | [139], 2025 |

| DHT22, AD8232 ECG, | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Ubidots cloud | Cloud server | Ubidots cloud | Dashboard, Email | Healthcare | [140], 2024 |

| AD8232 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Cloud based | Web based dashboard, Android mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app. | Healthcare | [58], 2020 |

| AD8232, NEO 6M, ADXL345, DS18B20, MAX32664, TCRT1000 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Google cloud | Cloud based | ThingSpeak, Blynk Cloud | Dashboard, mobile app. | Healthcare | [141], 2021 |

| AD8232 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Ubidots cloud | Cloud server | Ubidots cloud | Dashboard | Healthcare | [57], 2025 |

| ECG, EMG, EEG, EOG. | Wi-Fi, MQTT | SQLite3 | Web browser | Web-based Dashboard | Dashboard | Healthcare | [55], 2024 |

| DHT22, SPS30, FLIR Lepton3.5, SGP30 | Wi-Fi | Public database | Cloud AI engine | Web-based Dashboard, Mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app. | Healthcare | [54], 2024 |

| MAX30100, DHT11, MPU6050, Tobii Eye Tracker 4C, FlexiForce A401, TSL256, HCSR501 | NA | Local centralized data store | AI based | Dashboard | Dashboard | Healthcare | [53], 2024 |

| MAX30100, MQ135, DS18B20, DHT11, GP2Y1010 | Wi-Fi | Google spreadsheet | ThingSpeak, Blynk, IFTTT | Web-based ThingSpeak, Blynk mobile app. | LCD, Dashboard, mobile app. Email, SMS | Healthcare | [59], 2023 |

| Senseair S8 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak | Mobile app., LED, Dashboard, Voice | Healthcare | [142], 2025 |

| CK-101, LM35, | Wi-Fi | Google Firebase, MySQL | Web server | Web-based dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app. | Healthcare | [143], 2021 |

| MP503, KY-037, BME280, PPD42NS, TSL2561 | Wi-Fi, MQTT, Kafka | Cloud based | Web server | Web-based dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., LCD | Healthcare | [144], 2023 |

| TCRT 5000 | Wi-Fi | Google Firebase | Google Firebase | Web-based dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app. | Healthcare | [145], 2024 |

| DS18B20, SpO2 | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | MATLAB, ThingSpeak web server | Web-based dashboard, mobile app. | Mobile app., Dashboard, Buzzer | Healthcare | [146], 2025 |

| XKC-Y25-T12V, MAX30102, OX-201, W1209, | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Web server | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Healthcare | [147], 2022 |

| MAX30105, GY-906, DHT11 | Wi-Fi | Cloud based | Web server | Hand-held, SPPMS web-based dashboard, BLYNK mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., LCD | Healthcare | [148], 2022 |

| MAX30100, DS18B20, SHT30 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Node-Red cloud based | Node-Red dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app. | Healthcare | [149], 2024 |

| AD8232, MQ135, LM35, | Wi-Fi | Google Sheets Cloud based | Google Cloud Server | Figma and Bravo Studio based dashboard | Dashboard, Email, mobile app. | Healthcare | [150], 2021 |

| AD8232, DHT11, MQ gas sensor, MAX30100, ADXL335, | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Web server | Local PC, LCD, web-based dashboard | LCD, Dashboard | Healthcare | [151], 2023 |

| MAX30100, DHT11, MQ7, MQ135, DS18B20, AD8232 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | MS Excel data logging | MATLAB, Web server | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Healthcare | [152], 2025 |

| MAX30100, LM35, AD8232 | Wi-Fi, GSM | Google Firebase, SQL database | Python-Django web framework | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Healthcare | [153], 2021 |

| MPU6050, DS18B20, SEN15219 | Wi-Fi | Google Firebase | Web server | Web-based dashboard mobile app., Display | Dashboard, mobile app. | Healthcare | [154], 2022 |

| NEO-6M | Wi-Fi, LoRa, MQTT | SQLite | Web server | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard, | Healthcare, Automation | [155], 2025 |

| HTU21S, CCS811 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | PostgresSQL | ThingsBoard platform | ThingsBoard Dashboard | Dashboard | Healthcare | [156], 2021 |

| MPU6050, APDS-9008 | GSM | OneNet cloud-based database | OneNet cloud platform | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Healthcare, Automation | [157], 2021 |

| MAX30102, SW-420 | Wi-Fi | NA | Web server | Web-based dashboard, LCD | Dashboard, LCD, LEDs, buzzers | Healthcare | [158], 2025 |

| MAX30100, MLX90614, MQ135 | Wi-Fi | Cloud based | Cloud based | Web-based dashboard mobile app., LCD Display | Dashboard, mobile app, LCD | Healthcare | [159], 2024 |

| LM35, DHT11, MQ2, SpO2 | Wi-Fi | Cloud based | Cloud based | Web-based dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., buzzer | Healthcare | [160], 2024 |

| LM35, MAX30100, AD8232 | Wi-Fi, GSM | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak, OLED Display | Dashboard, mobile app., SMS, Display | Healthcare | [161], 2023 |

| ADXL335, AD8232, EMG Myoware | Wi-Fi, UDP | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server, IFTTT | Web-based ThingSpeak, LCD Display, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., LCD, buzzer | Healthcare | [162], 2022 |

| TVOC, CO2, PM, T, RH | LAN, Wi-Fi, Si-Fox, NB-IoT | AWS Cloud based | Amazon EC2 cloud | Web-based dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., SMS | Healthcare | [163], 2020 |

| GP2Y1014AU0F, DHT11, MiCS4514, MQ131, MICS5524, MG811, MS1100 | Wi-Fi, GSM, MQTT | ThingSpeak cloud-based, SD card | Web server | Web-based ThingSpeak, LCD Display, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., SMS | Healthcare, Automation | [164], 2023 |

| DHT11, MQ135, Soil moisture | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Cloud based | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [165], 2023 |

| DHT11, MQ135, KY-018, | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Node-RED, PageKite | Web-based PageKite | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [166], 2024 |

| BME680, MQ137 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | InfluxDB | InfluxDB, Node-Red | Web-based dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., SMS | Smart home and building | [89], 2025 |

| ZPHS01B multi-channel gas sensor | Wi-Fi | Google Firebase | Web server | Python Web Portal | Dashboard | Smart home and building, Healthcare | [90], 2022 |

| DHT11, MQ135, KY-018, KY026 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Node-RED, PageKite | Web-based PageKite | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [91], 2025 |

| SHT31, RC522, SGP30 | Wi-Fi, RFID | Local database | Web server | Web-based dashboard, LCD | Dashboard, LCD, buzzer | Smart home and building | [167], 2025 |

| HCSR501 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Blynk cloud based | Blynk app. | Blynk mobile app. | Mobile app. | Smart home and building | [168], 2025 |

| LM35, DHT11, MQ2, MAX30105 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | IBM Cloud Bluemix, Node-Red | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [169], 2021 |

| DHT11, HC-SR04 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Cloud based | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard, buzzer | Smart home and building | [170], 2022 |

| MQ135, MQ7, DHT22, BMP180, PMS7003, | Wi-Fi | OpenStack | Cloud based | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [171], 2020 |

| MQ135, MQ2, MQ9, DHT11 | Wi-Fi | Google Sheets | Web server, IFTTT | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [172], 2025 |

| HCSR505, MQ5, DHT11, MH-Z14, | Wi-Fi | ThingSpeak cloud-based | Web server | Mobile app. | Mobile app. | Smart home and building | [173], 2024 |

| DHT11, GL5528, SW420, HC-SR501, MQ2 | Wi-Fi | MySQL, MariaDB | Web server | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [88], 2022 |

| MA5990–0, Si7021, TSic-206 | Wi-Fi | Cloud based | Web server | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [174], 2024 |

| KY005, DHT22, DS3231 | Wi-Fi | Google Firebase | Google Firebase | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [94], 2025 |

| SCD30, SFA30, PMS5003, MiCS-VZ-89TE, RD200P2, Netatmo | Wi-Fi, Bluetooth | Cloud based | Cloud based, Node-RED | Web-based dashboard | Dashboard | Smart home and building | [175], 2023 |

| DHT11, MQ-135 | Wi-Fi, MQTT | Cloud based | Cloud based | Mobile app., LCD Display | Mobile app., LCD, buzzer | Smart home and building | [176], 2023 |

| TGS4160, DHT11, BH1750 | Wi-Fi | OneNET cloud | OneNET cloud platform | OneNET view Dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., buzzer | Smart home and building | [177], 2025 |

| DHT11, MQ-135, GL5528, | Wi-Fi | Cloud based, MySQL | Cloud based, AI | Web-based dashboard, mobile app. | Dashboard, mobile app., buzzer | Smart home and building | [178], 2024 |