Are Ionospheric Disturbances Spatiotemporally Invariant Earthquake Precursors? A Multi-Decadal 100-Station Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation: Lithosphere–Atmosphere–Ionosphere Coupling

3. Data

Data Acquisition and Station Network

4. Preprocessing Pipeline

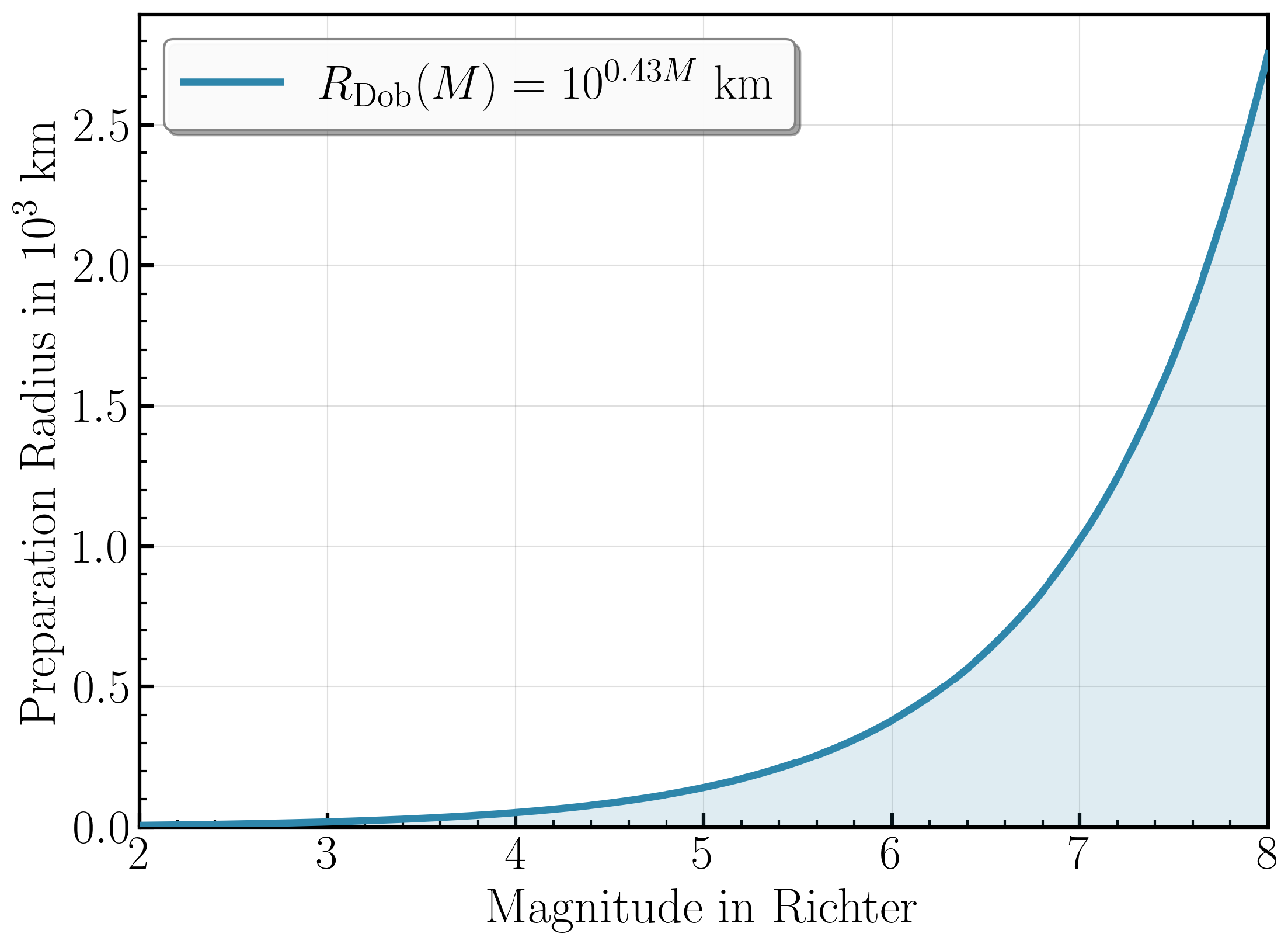

4.1. Spatial Filtering via Dobrovolsky Radius

4.2. Temporal Window Construction

4.3. Feature Extraction via Multi-Scale Statistical Aggregation

4.4. Quality Assurance and Temporal Integrity

5. Feature Selection and Data Leakage Mitigation

5.1. Exclusion of Spurious Spatiotemporal Features

5.2. Ensemble-Based Feature Ranking

6. Temporal Data Splitting and Distribution Balance

6.1. The Critical Importance of Temporal Validation

6.2. The Distribution Shift Problem

6.3. Stratified Temporal Splitting

7. Methodology

7.1. Model Selection and Hyperparameter Tuning

7.2. Evaluation Protocol

8. Experimental Results

Impact of Test Set Size on Model Performance

9. Conclusions and Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting | KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| AGW | Acoustic-Gravity Wave | Kp | Planetary K-index |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance | LAIC | Lithosphere-Atmosphere-Ionosphere Coupling |

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve | LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| B0 | B0 bottomside thickness parameter | M | Earthquake Magnitude |

| B1 | B1 topside thickness parameter | M(3000)F2 | Maximum usable frequency factor for 3000 km |

| CatBoost | Categorical Boosting | MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| Dst | Disturbance Storm Time index | MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| F1 | Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall | MD | Maximum usable frequency factor |

| F10.7 | Solar radio flux at 10.7 cm | MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| foE | Critical frequency of E layer | MUFD | Maximum Usable Frequency Distance |

| foEs | Critical frequency of sporadic E | Coefficient of Determination | |

| foF1 | Critical frequency of F1 layer | RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| foF2 | Critical frequency of F2 layer | ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| hE | Virtual height of E layer | scaleF2 | F2 layer scale height |

| hEs | Virtual height of sporadic E | SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| hF | Virtual height of F layer | TEC | Total Electron Content |

| hF2 | Virtual height of F2 layer | ULF | Ultra Low Frequency |

| hmE | Height of max. density in E layer | VLF | Very Low Frequency |

| hmF1 | Height of max. density in F1 layer | XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| hmF2 | Height of max. density in F2 |

Appendix A. Selected Features

- 1.

- B1_max_21d—B1 topside thickness parameter maximum (21-day window);

- 2.

- B1_max_30d—B1 topside thickness parameter maximum (30-day window);

- 3.

- B0_variance_second_half_7d—B0 bottomside thickness parameter variance (second half of 7-day window);

- 4.

- B1_max_14d—B1 topside thickness parameter maximum (14-day window);

- 5.

- B0_std_21d—B0 bottomside thickness parameter standard deviation (21-day window);

- 6.

- hmF2_anomaly_max_abs_3d—F2 layer height maximum absolute anomaly (3-day window);

- 7.

- foF2_variance_first_half_30d—F2 critical frequency variance (first half of 30-day window);

- 8.

- B0_trend_slope_1d—B0 bottomside thickness parameter linear trend slope (1-day window);

- 9.

- B1_variance_second_half_30d—B1 topside thickness parameter variance (second half of 30-day window);

- 10.

- TEC_anomaly_early_vs_late_30d—TEC anomaly temporal contrast (early vs. late 30-day window);

- 11.

- solar_F10_7_min—Minimum solar radio flux at 10.7 cm;

- 12.

- TEC_trend_slope_3d—Total Electron Content linear trend slope (3-day window);

- 13.

- hmE_min_1d—E layer height minimum (1-day window);

- 14.

- B1_q25_7d—B1 topside thickness parameter 25th percentile (7-day window);

- 15.

- solar_F10_7_max—Maximum solar radio flux at 10.7 cm;

- 16.

- TEC_trend_slope_1d—Total Electron Content linear trend slope (1-day window);

- 17.

- B1_n_anomalies_gt_2_3d—Count of B1 anomalies exceeding 2 (3-day window);

- 18.

- hmE_variance_second_half_1d—E layer height variance (second half of 1-day window);

- 19.

- solar_F10_7_mean—Mean solar radio flux at 10.7 cm;

- 20.

- B1_anomaly_max_abs_3d—B1 topside thickness parameter maximum absolute anomaly (3-day window);

- 21.

- B0_variance_first_half_14d—B0 bottomside thickness parameter variance (first half of 14-day window);

- 22.

- TEC_max_30d—Total Electron Content maximum (30-day window);

- 23.

- B1_n_anomalies_gt_2_14d—Count of B1 anomalies exceeding 2 (14-day window);

- 24.

- foF2_n_anomalies_gt_2_3d—Count of F2 critical frequency anomalies exceeding 2 (3-day window);

- 25.

- hmE_q75_14d—E layer height 75th percentile (14-day window).

References

- Pulinets, S.; Ouzounov, D. Lithosphere–Atmosphere–Ionosphere Coupling (LAIC) model—An unified concept for earthquake precursors validation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2010, 41, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Chen, Y.I.; Chuo, Y.J.; Chen, C.S. A statistical investigation of preearthquake ionospheric anomaly. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2006, 111, A05304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heki, K. Ionospheric electron enhancement preceding the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L17312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzounov, D.; Pulinets, S.; Hattori, K.; Taylor, P. (Eds.) Pre-Earthquake Processes: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Earthquake Prediction Studies; AGU Geophysical Monograph; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masci, F.; Thomas, J.; Villani, F.; Secan, J.; Rivera, N. On the onset of ionospheric precursors 40 min before strong earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2015, 120, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Love, J.; Johnston, M.; Yumoto, K. On the reported magnetic precursor of the 1993 Guam earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, 16301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.; Herrera, V.M.V. Earthquake Precursors: The Physics, Identification, and Application. Geosciences 2024, 14, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirage, C.S.N.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Hao, H.; Liu, W.; Ni, P. Structural damage identification based on autoencoder neural networks and deep learning. Eng. Struct. 2018, 172, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kurata, M.; Nakashima, M. Evaluating damage extent of fractured beams in steel moment-resisting frames using dynamic strain responses. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2015, 44, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Y.I.; Pulinets, S.; Tsai, Y.; Chuo, Y. Seismo-ionospheric signatures prior to M≥6.0 Taiwan earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2000, 27, 3113–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaohui, D.; Zhang, X. Ionospheric Disturbances Possibly Associated with Yangbi Ms6.4 and Maduo Ms7.4 Earthquakes in China from China Seismo Electromagnetic Satellite. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmeir, C.; Benítez, J. On the use of cross-validation for time series predictor evaluation. Inf. Sci. 2012, 191, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florios, K.; Contopoulos, I.; Tatsis, G.; Christofilakis, V.; Chronopoulos, S.; Repapis, C.; Tritakis, V. Possible earthquake forecasting in a narrow space-time-magnitude window. Earth Sci. Inform. 2021, 14, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritakis, V.; Contopoulos, I.; Mlynarczyk, J.; Chaniadakis, E.; Kubisz, J. Evaluation of the Quasi-Pre-Seismic Schumann Resonance Signals in the Greek Area During Five Years of Observations (2020–2025). Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, R.J.; Jackson, D.D.; Kagan, Y.Y.; Mulargia, F. Earthquakes Cannot Be Predicted. Science 1997, 275, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, M.; Aceves, R.; Park, S.; Geller, R.; Jackson, D.; Kagan, Y.; Mulargia, F. Cannot Earthquakes Be Predicted? Science 1997, 278, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Izutsu, J.; Schekotov, A.; Yang, S.S.; Solovieva, M.; Budilova, E. Lithosphere–Atmosphere–Ionosphere Coupling Effects Based on Multiparameter Precursor Observations for February–March 2021 Earthquakes (M 7) in the Offshore of Tohoku Area of Japan. Geosciences 2021, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.; Ouzounov, D.; Karelin, A.; Boyarchuk, K.; Pokhmelnykh, L. The physical nature of thermal anomalies observed before strong earthquakes. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2006, 31, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicerone, R.D.; Ebel, J.E.; Britton, J. A systematic compilation of earthquake precursors. Tectonophysics 2009, 476, 371–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Aplin, K.; Rycroft, M. Atmospheric electricity coupling between earthquake regions and the ionosphere. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2010, 72, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woith, H. Radon earthquake precursor: A short review. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2015, 224, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauksson, E. Radon content of groundwater as an earthquake precursor: Evaluation of worldwide data and physical basis. J. Geophys. Res. B 1981, 86, 9397–9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnan, S.; Akgül, T.; Seyis, C.; Saatçılar, R.; Baykut, S.; Ergintav, S.; Baş, M. Geochemical monitoring in the Marmara region (NW Turkey): A search for precursors of seismic activity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2008, 113, B03401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastefanou, C. Variation of radon flux along active fault zones in association with earthquake occurrence. Radiat. Meas. 2010, 45, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbein, J.; Borcherdt, R.; Dreger, D.; Fletcher, J.; Hardebeck, J.; Hellweg, M.; Ji, C.; Johnston, M.; Murray, J.; Nadeau, R.; et al. Preliminary Report on the 28 September 2004, M 6.0 Parkfield, California Earthquake. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2005, 76, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molchanov, O.; Hayakawa, M. Seismo Electromagnetics and Related Phenomena: History and Latest Results; TERRAPUB: Tokyo, Japan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hegai, V.; Kim, V.; Liu, J. The ionospheric effect of atmospheric gravity waves excited prior to strong earthquake. Adv. Space Res. 2006, 37, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astafyeva, E.; Heki, K.; Kiryushkin, V.; Afraimovich, E.; Shalimov, S. Two-mode long-distance propagation of coseismic ionosphere disturbances. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2009, 114, A10307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komjathy, A.; Galvan, D.A.; Stephens, P.; Butala, M.D.; Akopian, V.; Wilson, B.; Verkhoglyadova, O.; Mannucci, A.J.; Hickey, M. Detecting ionospheric TEC perturbations caused by natural hazards using a global network of GPS receivers: The Tohoku case study. Earth Planets Space 2012, 64, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaki, K.; Hayakawa, M.; Molchanov, O. The role of gravity waves in the lithosphere–ionosphere coupling, as revealed from the subionospheric LF propagation data. In Seismo Electromagnetics: Lithosphere-Atmosphere-Ionosphere Coupling; TERRAPUB: Tokyo, Japan, 2002; pp. 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, F. Pre-earthquake signals: Underlying physical processes. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, P.A.; Sarlis, N.V.; Skordas, E.S. Natural Time Analysis: The New View of Time; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.; Chmyrev, V.; Hayakawa, M. Electrodynamic Coupling of Lithosphere-Atmosphere-Ionosphere of the Earth; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.L.; Lee, L.C.; Huba, J.D. An improved coupling model for the lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere system. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2014, 119, 3189–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W. Natural magnetic disturbance fields, not precursors, preceding the Loma Prieta earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, A05307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinisch, B.; Galkin, I. Global Ionospheric Radio Observatory (GIRO). Earth Planets Space 2011, 63, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.H.; Papitashvili, N.E. Solar wind spatial scales in and comparisons of hourly Wind and ACE plasma and magnetic field data. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2005, 110, A02209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey, Earthquake Hazards Program. Advanced National Seismic System (ANSS) Comprehensive Catalog of Earthquake Events and Products; Various: Reston, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolsky, I.P.; Zubkov, S.I.; Miachkin, V.I. Estimation of the size of earthquake preparation zones. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1979, 117, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2000, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random Search for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982, 143, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchor, N.A. MUC-4 evaluation metrics. In Proceedings of the Message Understanding Conference, McLean, VA, USA, 16–18 June 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

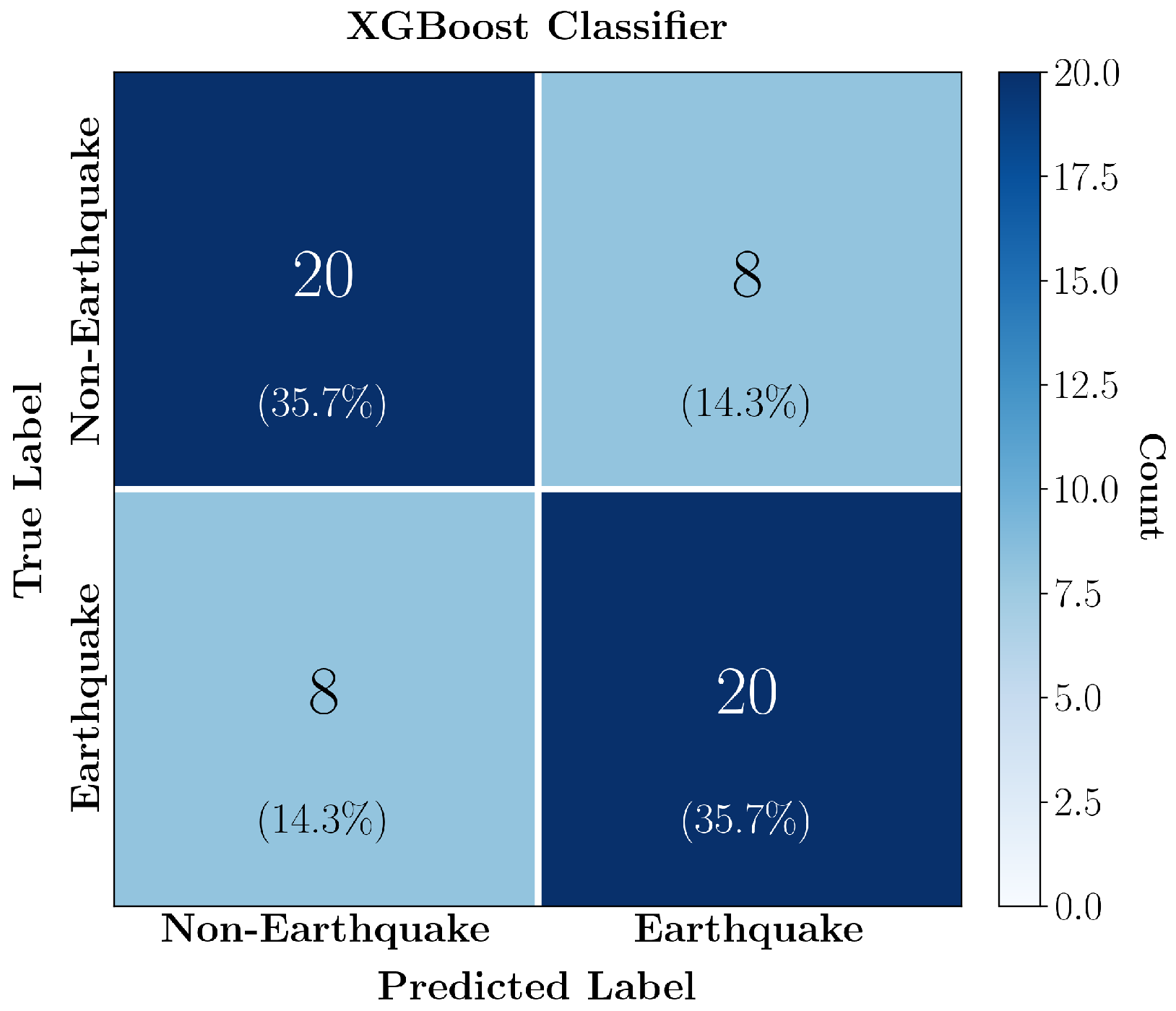

| Model | F1-W | MCC | AUC | Bal-Acc | Kappa | G-Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.714 | 0.429 | 0.774 | 0.714 | 0.429 | 0.714 |

| Extra Trees | 0.714 | 0.429 | 0.773 | 0.714 | 0.429 | 0.714 |

| Neural Network | 0.713 | 0.433 | 0.730 | 0.714 | 0.429 | 0.711 |

| Random Forest | 0.696 | 0.393 | 0.742 | 0.696 | 0.393 | 0.696 |

| Histogram Gradient Boosting | 0.696 | 0.393 | 0.781 | 0.696 | 0.393 | 0.696 |

| LightGBM | 0.679 | 0.357 | 0.736 | 0.679 | 0.357 | 0.679 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.678 | 0.358 | 0.719 | 0.679 | 0.357 | 0.678 |

| Deep NN | 0.625 | 0.250 | 0.714 | 0.625 | 0.250 | 0.625 |

| AdaBoost | 0.571 | 0.143 | 0.615 | 0.571 | 0.143 | 0.571 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.571 | 0.143 | 0.619 | 0.571 | 0.143 | 0.571 |

| KNN | 0.571 | 0.143 | 0.606 | 0.571 | 0.143 | 0.570 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaniadakis, E.; Contopoulos, I.; Tritakis, V. Are Ionospheric Disturbances Spatiotemporally Invariant Earthquake Precursors? A Multi-Decadal 100-Station Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13218. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413218

Chaniadakis E, Contopoulos I, Tritakis V. Are Ionospheric Disturbances Spatiotemporally Invariant Earthquake Precursors? A Multi-Decadal 100-Station Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13218. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413218

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaniadakis, Evangelos, Ioannis Contopoulos, and Vasilis Tritakis. 2025. "Are Ionospheric Disturbances Spatiotemporally Invariant Earthquake Precursors? A Multi-Decadal 100-Station Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13218. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413218

APA StyleChaniadakis, E., Contopoulos, I., & Tritakis, V. (2025). Are Ionospheric Disturbances Spatiotemporally Invariant Earthquake Precursors? A Multi-Decadal 100-Station Study. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13218. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413218