Radicular Aberrations of Mandibular Third Molars: Relevance for Oral Surgery—A Comprehensive Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

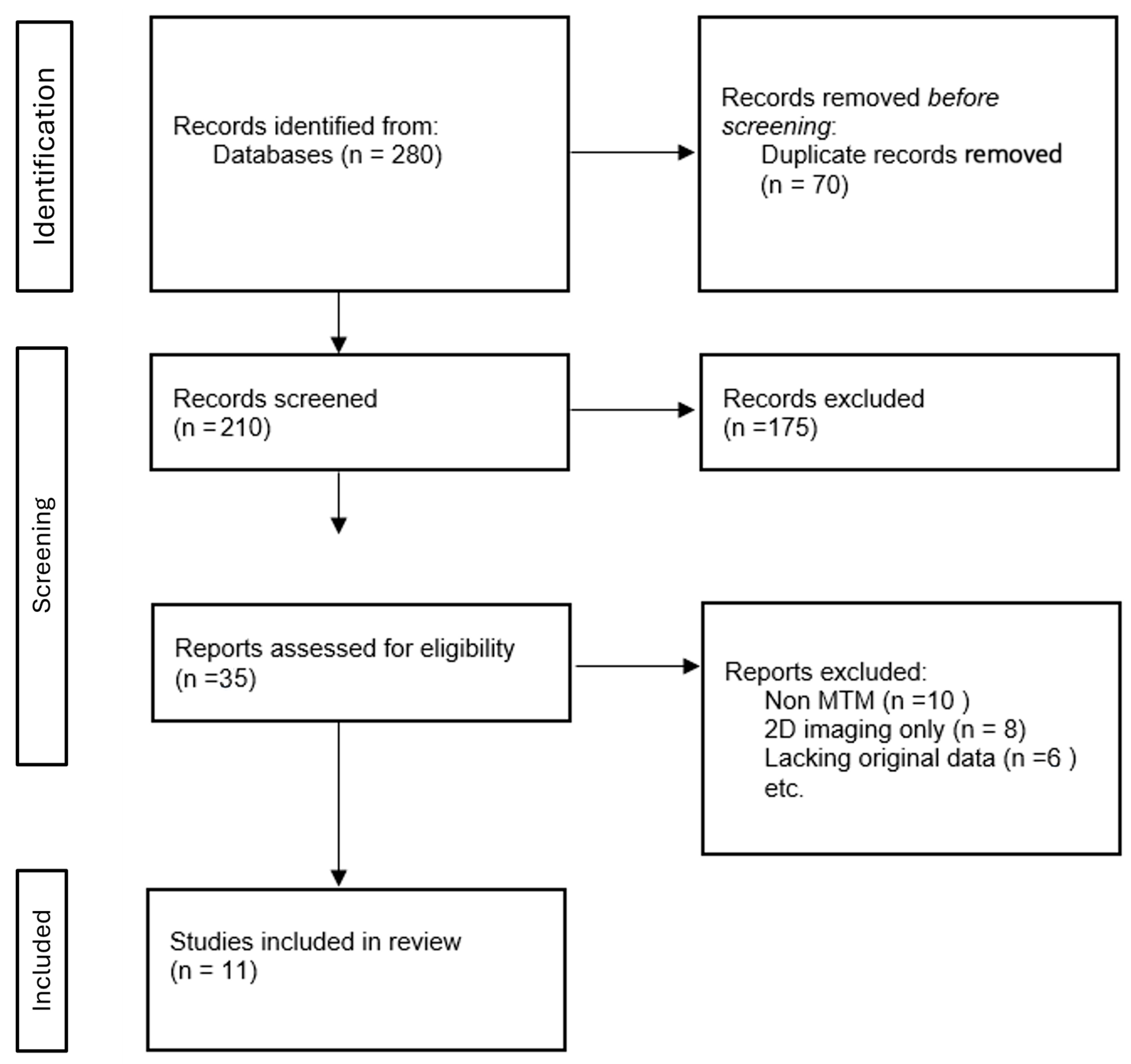

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

- Lacked original or detailed morphological data;

- Involved non-human or deciduous dentition;

- Were not written in English;

- Addressed aberrations unrelated to root anatomy.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

3. Results

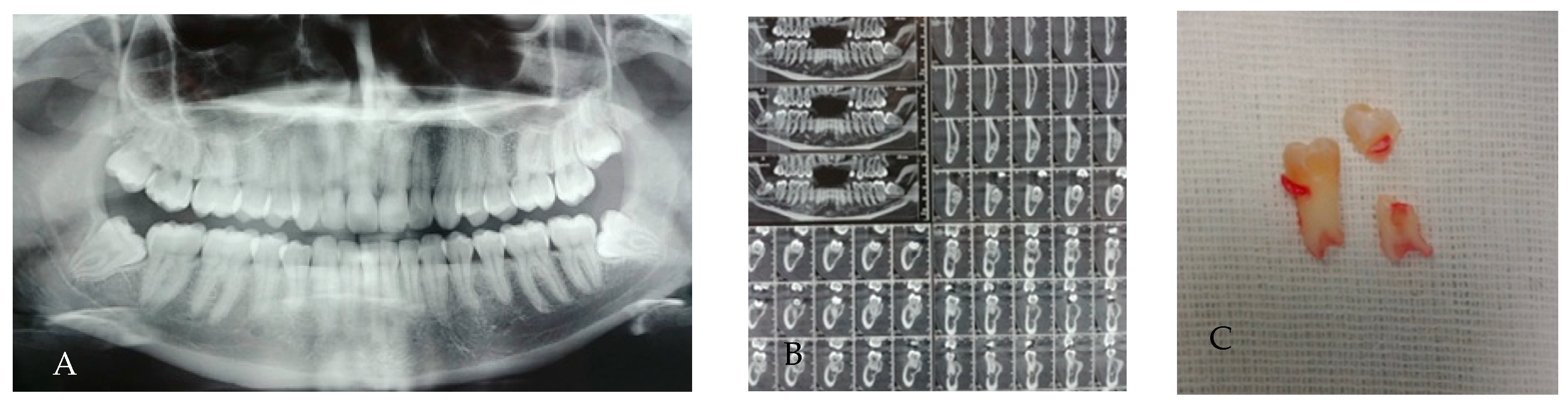

3.1. Root Number Variation (Single, Two, Three or More Roots)

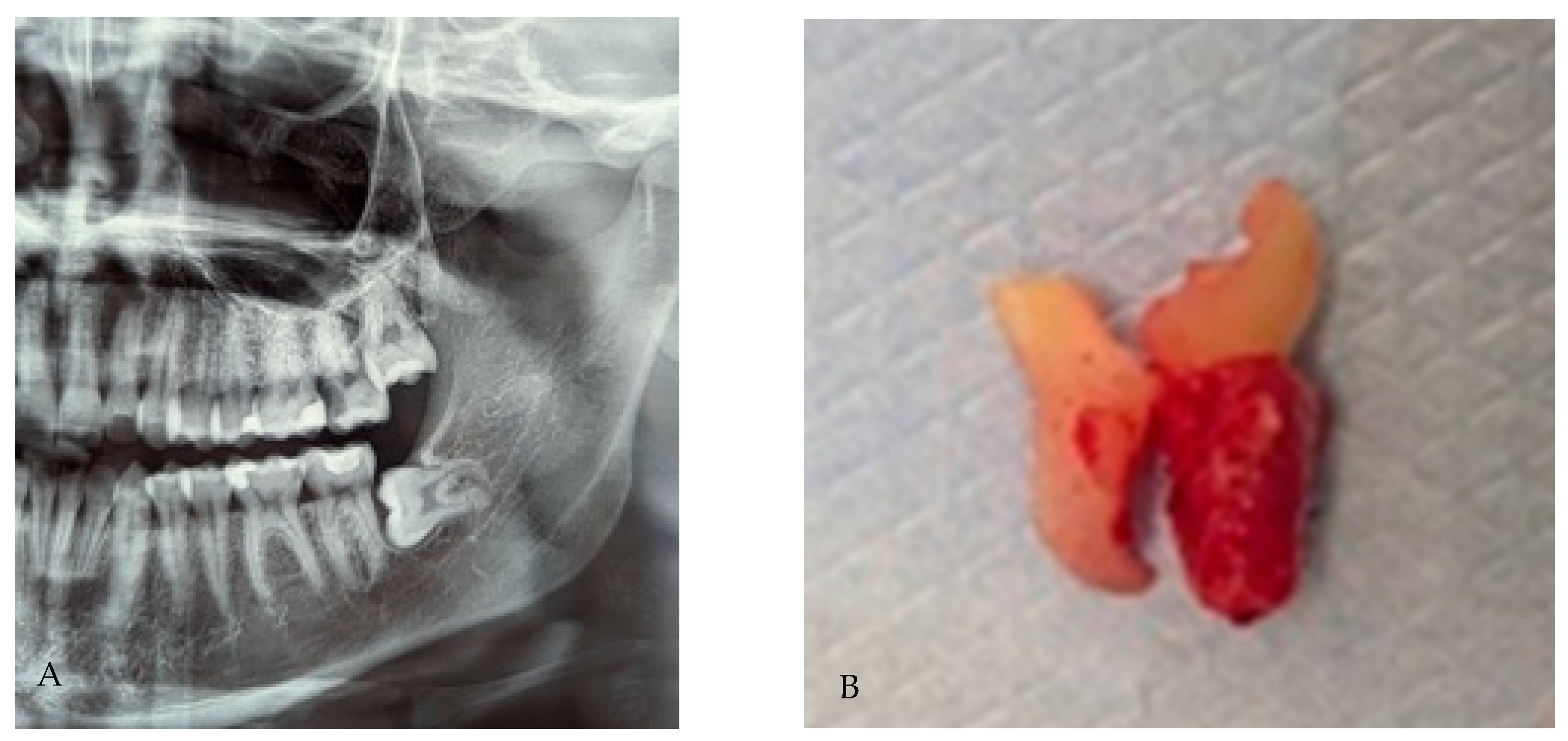

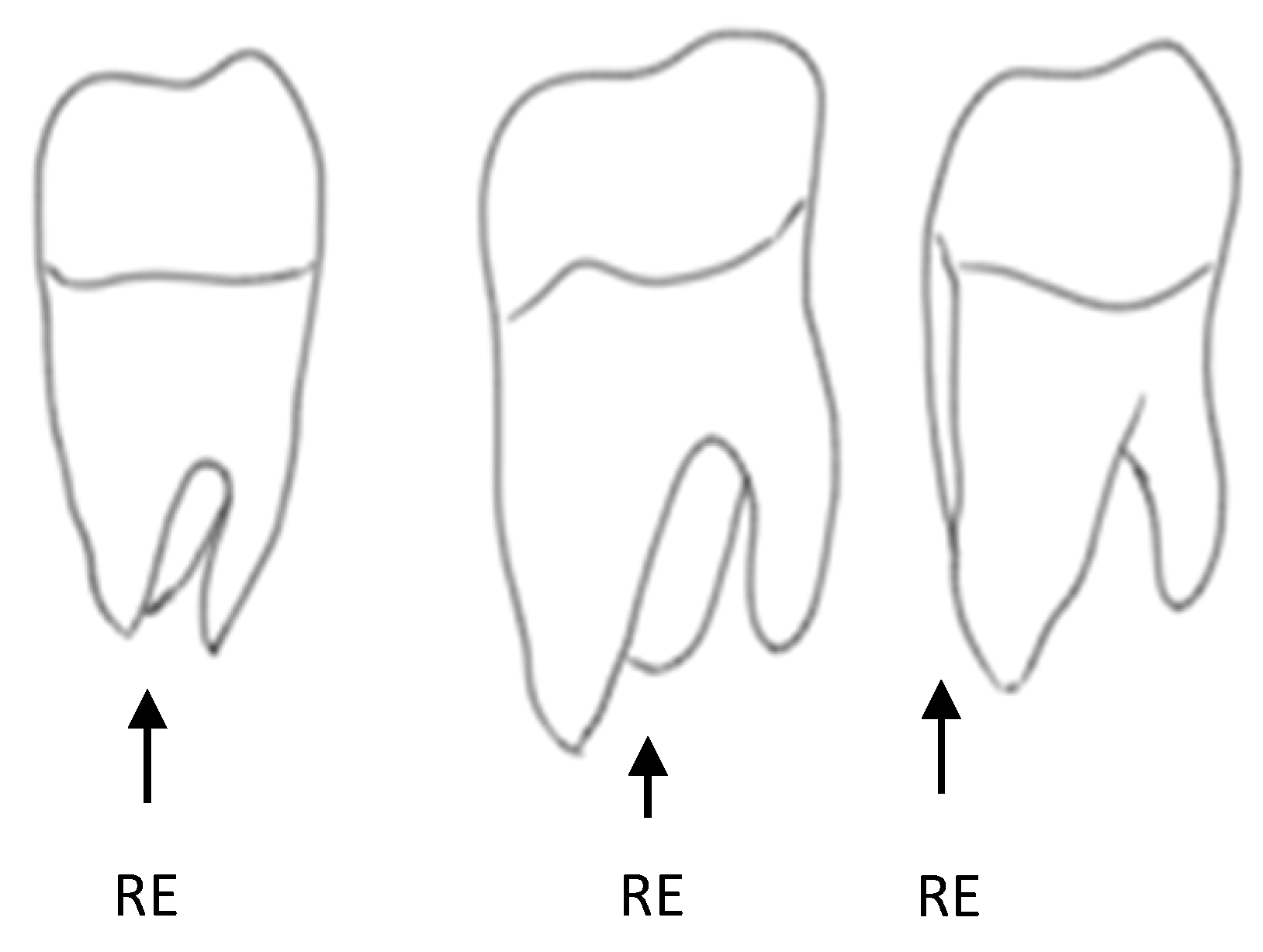

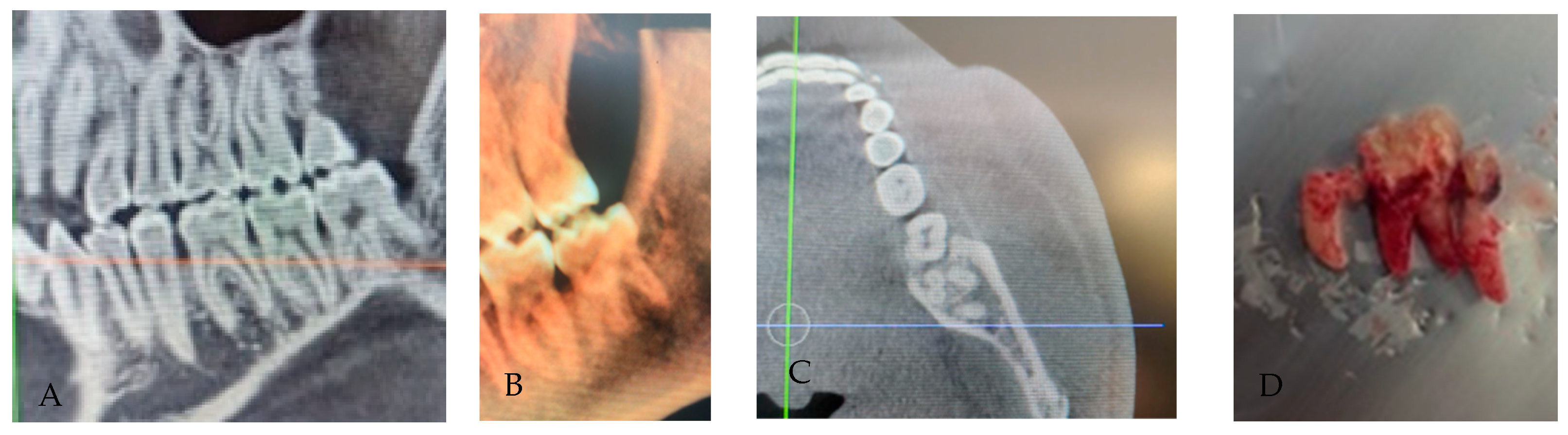

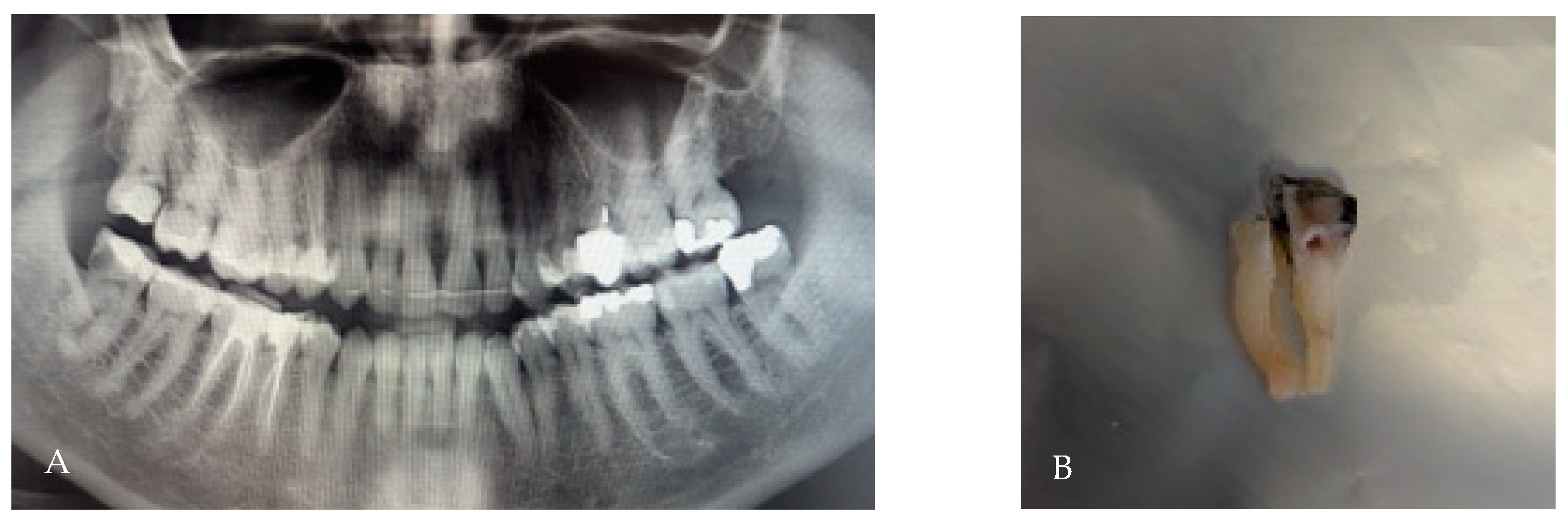

3.2. Radix Entomolaris

- Type I: straight root/canal;

- Type II: curvature in the coronal third, followed by a straight continuation;

- Type III: curvature in the coronal third with an additional buccal curvature in the apical third.

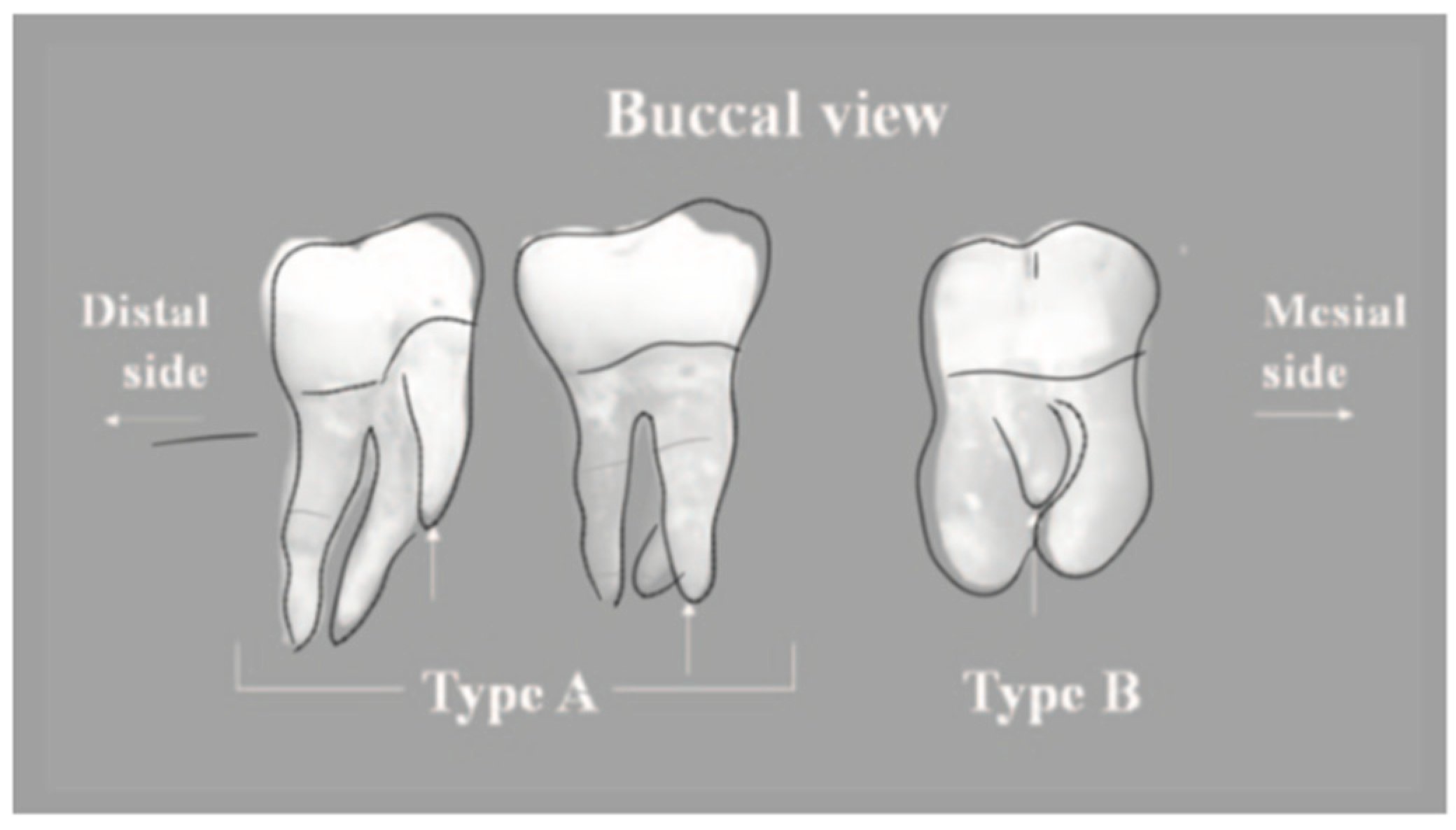

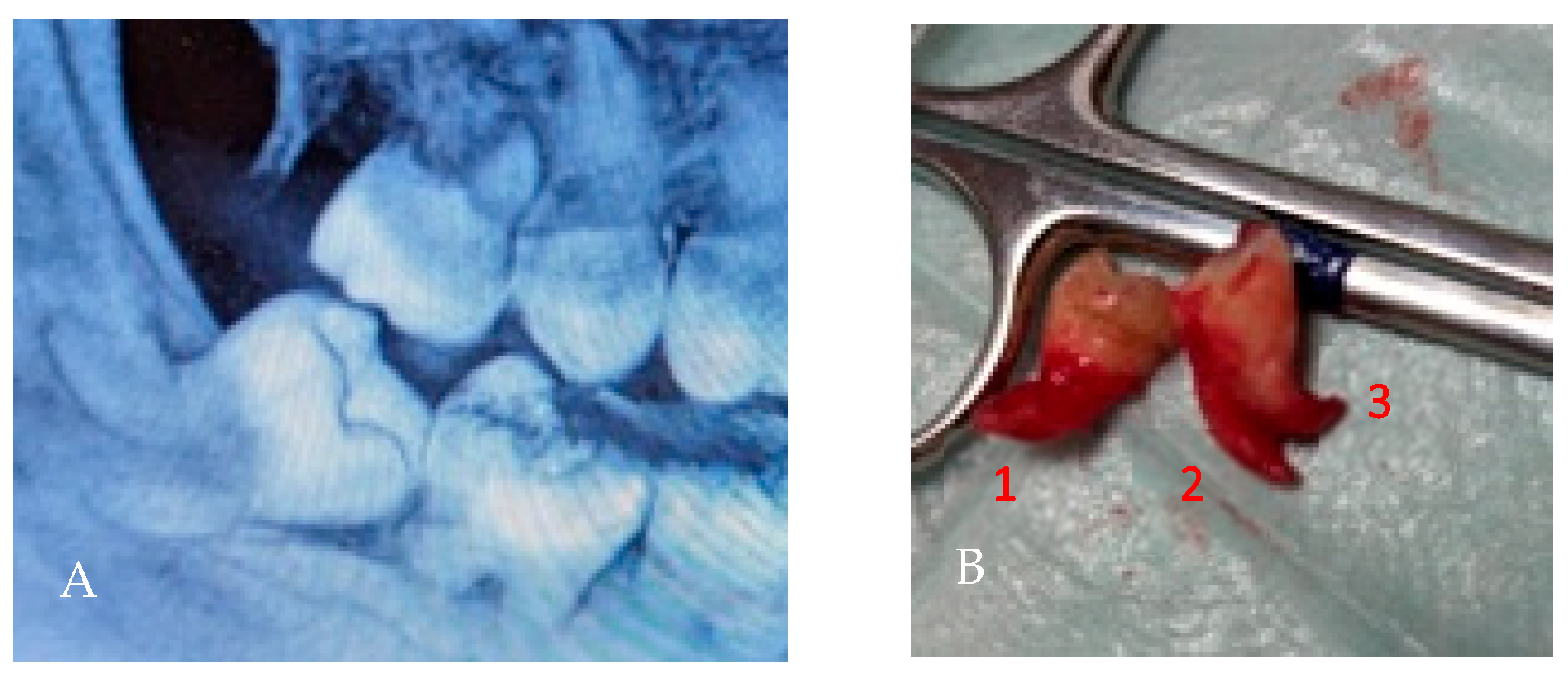

3.3. Radix Paramolaris

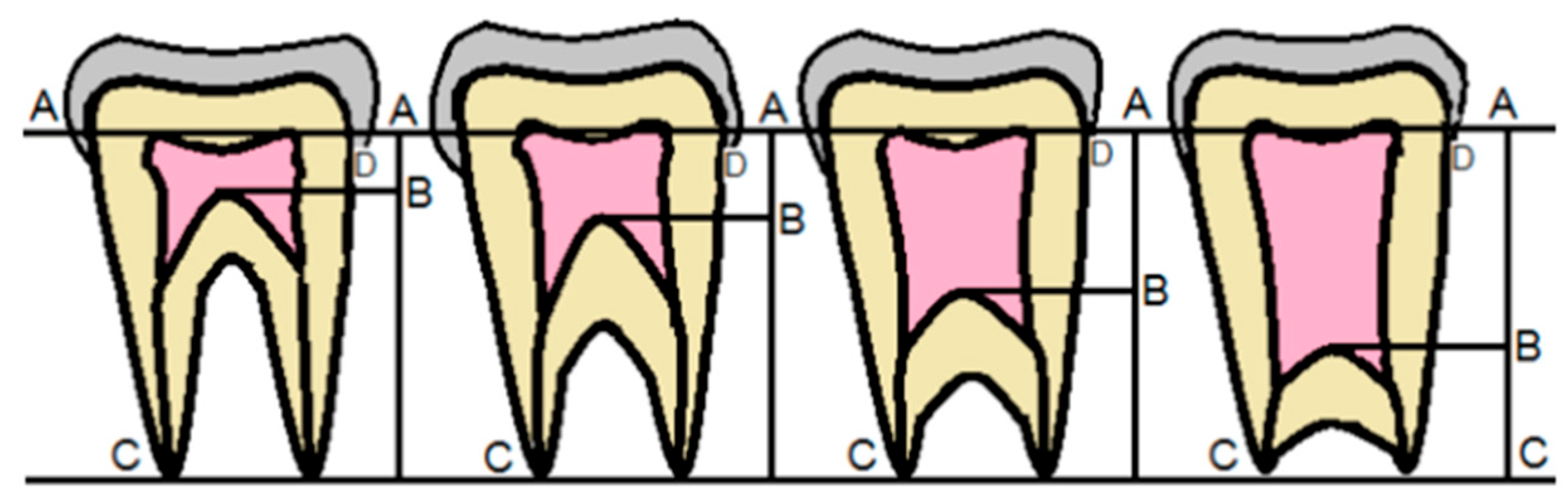

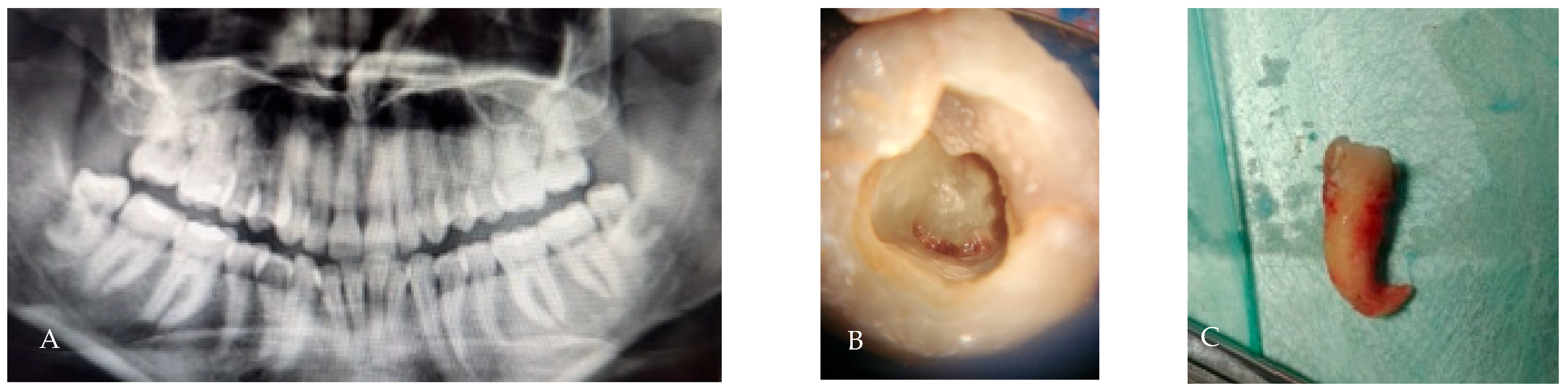

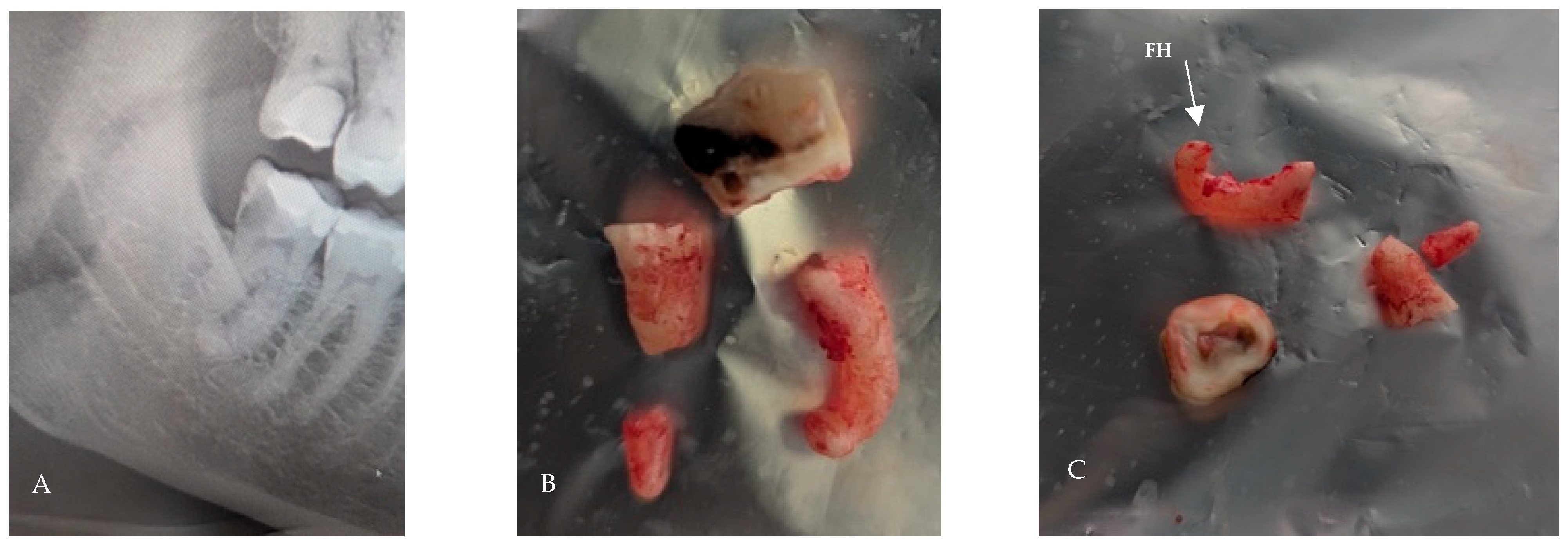

3.4. Taurodontism

- Hypotaurodont: mild displacement; furcation slightly apical, root length relatively preserved.

- Mesotaurodont: moderate displacement; larger pulp chamber, shorter roots.

- Hypertaurodont: severe displacement; very elongated pulp chamber, minimal root length, furcation close to the apex.

3.5. Root Fusion

3.6. C-Shaped Morphology

- C1: continuous C-shaped canal.

- C2: semicolon-shaped (due to discontinuation of the “C”).

- C3: two or more discrete canals without a clear C-shape.

- C4: single round or oval canal.

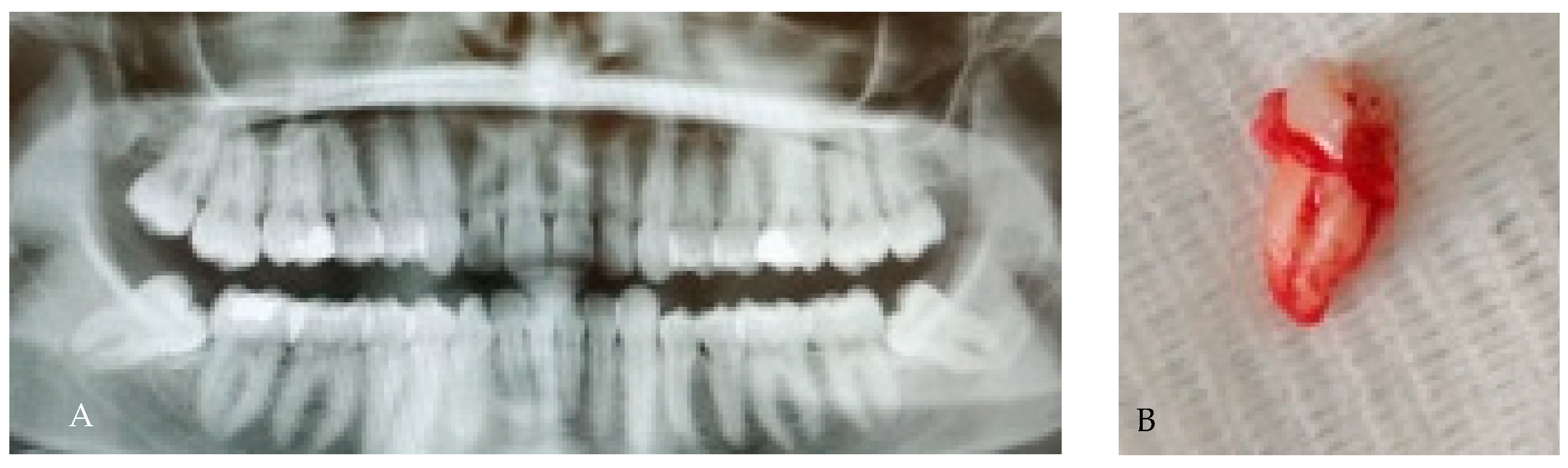

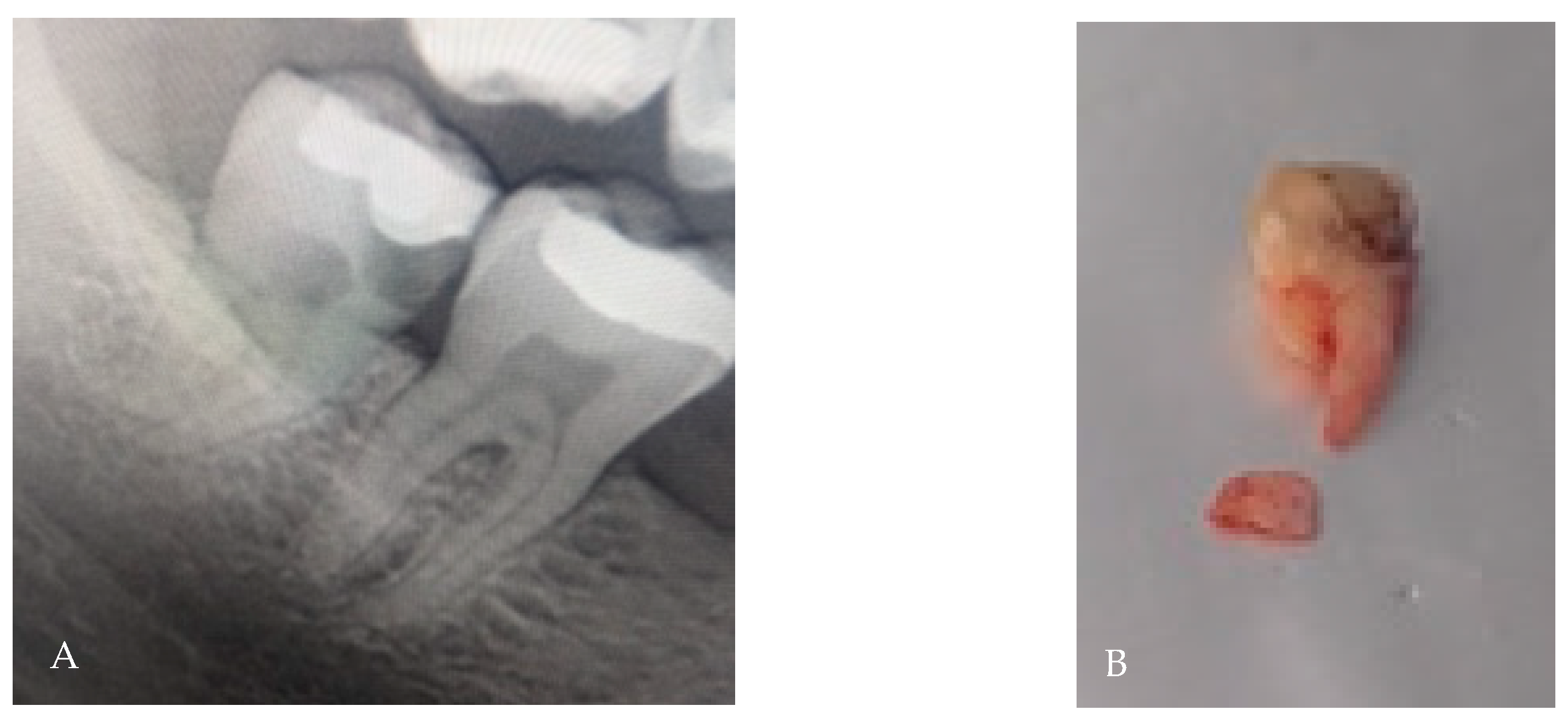

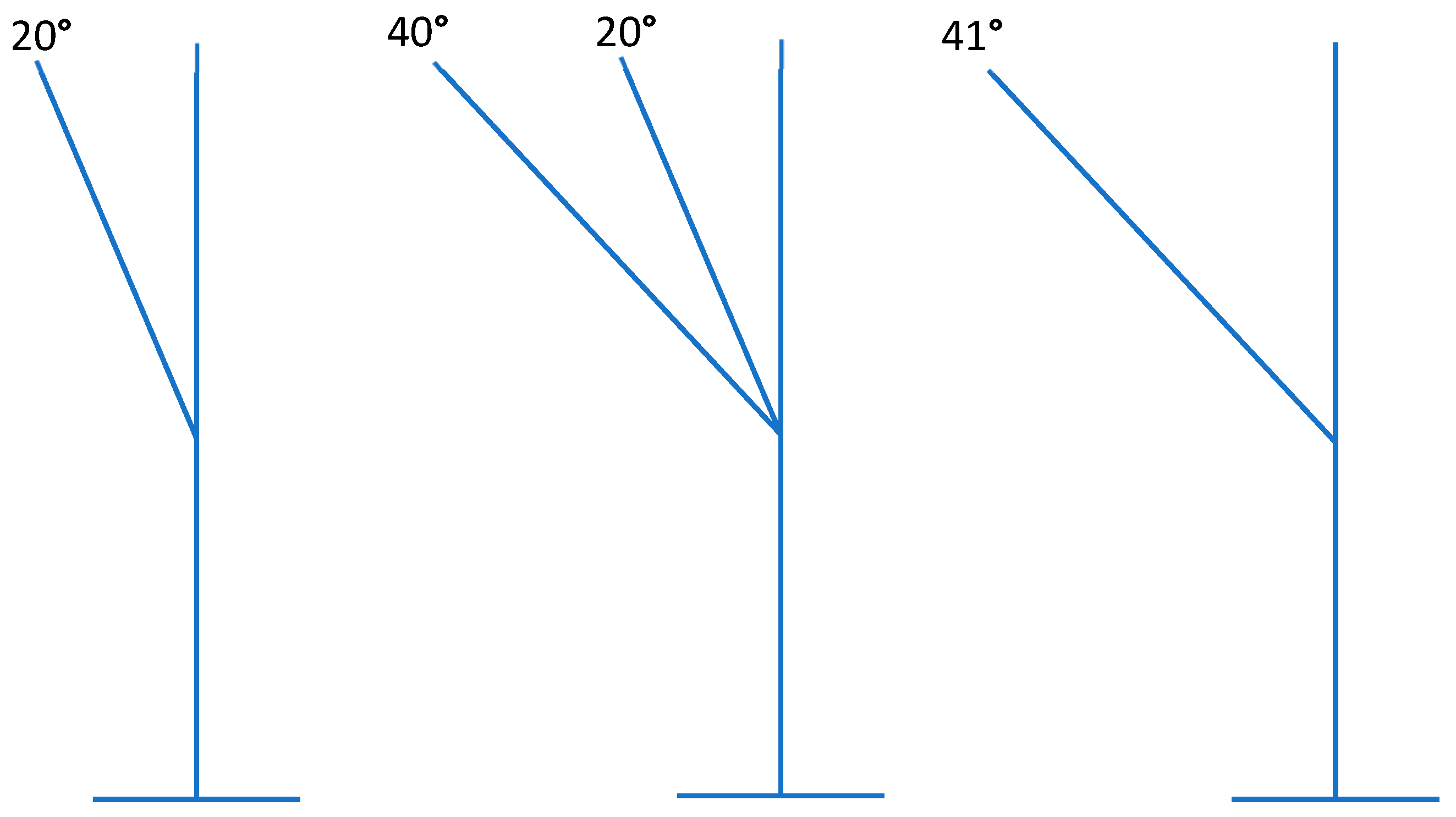

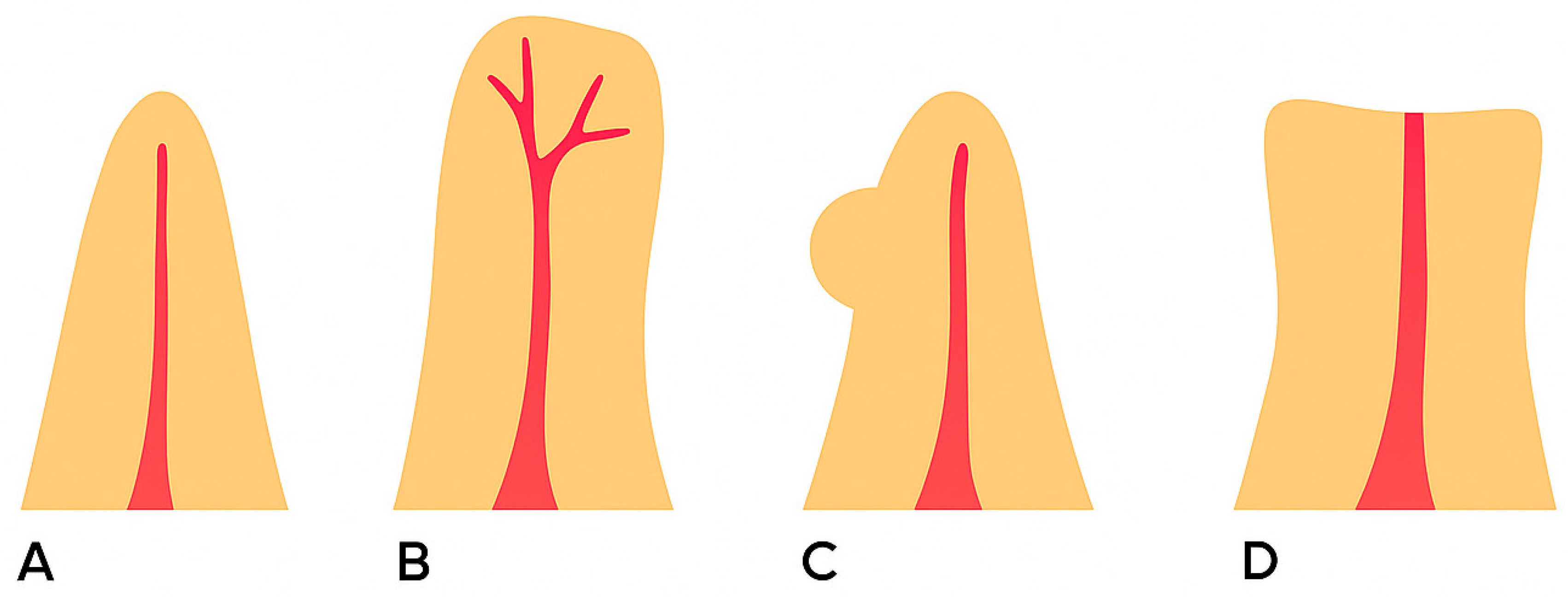

3.7. Dilaceration/Apical Curvature

3.8. Hypercementosis

- Club-shaped hypercementosis: root exhibits a generalized, smooth, thickened contour; extraction may be more difficult due to increased root diameter.

- Focal hypercementosis: localized nodular deposits on one or more aspects of the root; may create mechanical undercuts, increasing the risk of root fracture during luxation.

- Circular (or circumferential) hypercementosis: uniform thickening encircling the root, often leading to ankylosis-like resistance during extraction.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santosh, P. Impacted mandibular third molars: Review of literature and a proposal of a combined clinical and radiological classification. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2015, 5, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondeau, F.; Daniel, N.G. Extraction of impacted mandibular third molars: Postoperative complications and their risk factors. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 73, 325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jing, Q.; Song, H.; Huang, H.; Shi, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wang, D. Characterizations of three-dimensional root morphology and topological location of mandibular third molars by cone-beam computed tomography. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2023, 45, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hupp, J.R.; Ellis, E.; Tucker, M.R. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 7th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaeminia, H.; Meijer, G.J.; Soehardi, A.; Borstlap, W.A.; Mulder, J.; Vlijmen, O.J.C.; Bergè, S.J.; Maal, T.J.J. The use of cone beam CT for the removal of wisdom teeth changes the surgical approach compared with panoramic radiography: A pilot study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 40, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyank, H.; Viswanath, B.; Sriwastwa, A.; Hegde, P.; Abdul, N.S.; Golgeri, M.S.; Mathur, H. Radiographical evaluation of morphological alterations of mandibular third molars: A cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e34114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiran-Us, S.; Benjavongkulchai, S.; Antanit, C.; Thanadrob, P.; Thongpet, P.; Onrawijit, A. Prevalence of C-shaped canals and three-rooted mandibular molars using CBCT in a selected Thai population. Iran. Endod. J. 2021, 16, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Miloglu, O.; Cakici, F.; Çağlayan, F.; Yilmaz, A.B.; Demirkaya, F. The prevalence of root dilacerations in a Turkish population. Oral Radiol. 2010, 26, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcić, A.; Jukić, S.; Brzović, V.; Miletić, I.; Pelivan, I.; Anić, I. Prevalence of root dilaceration in adult dental patients in Croatia. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 102, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, F.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Tian, Y. Prevalence of taurodontism in individuals in Northwest China determined by cone-beam computed tomography images. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızı, D.; Aksoy, U.; Aksoy, S.; İnönü, N.; Orhan, K. Evaluation of taurodont and pyramidal mandibular molars prevalence in a group of Turkish Cypriot population by cone beam computed tomography. Cyprus J. Med. Sci. 2025, 10, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohbayashi, N.; Wamasing, P.; Tonami, K.; Kurabayashi, T. Incidence of hypercementosis in mandibular third molars determined using cone beam computed tomography. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 63, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, O.; Alexandersen, V. Radix entomolaris: Identification and clinical considerations. Int. Endod. J. 1990, 23, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, M.G.; Tsai, C.C.; Jou, M.J.; Chen, W.L.; Chang, Y.F.; Chen, S.Y.; Cheng, H.W. Prevalence of three-rooted mandibular first molars among Taiwanese individuals. J. Endod. 2007, 33, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calberson, F.L.; De Moor, R.J.; Deroose, C.A. The radix entomolaris and paramolaris: Clinical approach in endodontics. J. Endod. 2007, 33, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopatkar, J.; Ikhar, A.; Nikhade, P.; Chandak, M.; Agrawal, P.; Nikhade, P.P. Navigating challenges in the management of mandibular third molars with Radix paramolaris: A case report. Cureus 2023, 15, e45744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.; de Ataide, I.; Wagle, R. C-shaped root canal configuration: A review of literature. J. Conserv. Dent. 2014, 17, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, G.D.T.T.; Peralta-Mamani, M.; da Silva, A.D.F.M.; Rubira, C.F.; Honório, H.M.; Rubira-Bullen, I.F. Influence of cone beam computed tomography versus panoramic radiography on the surgical technique of third molar removal: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachoo, V.; Taetragool, U.; Pianchoopat, P.; Sukitporn-Udom, C.; Morakrant, N.; Warin, K. Deep learning for predicting the difficulty level of removing the impacted mandibular third molar. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantilieraki, E.; Delantoni, A.; Angelopoulos, C.; Beltes, P. Evaluation of root and root canal morphology of mandibular first and second molars in a Greek population: A CBCT study. Eur. Endod. J. 2019, 4, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarca, J.; Duran, M.; Parra, D.; Steinfort, K.; Zaror, C.; Monardes, H. Root morphology of mandibular molars: A CBCT study. Folia Morphol. 2020, 79, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DLi, S.; Min, Z.; Wang, T.; Hou, B.; Su, Z.; Zhang, C. Prevalence and root canal morphology of taurodontism analyzed by cone-beam computed tomography in Northern China. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourneau, E.; Olszewski, R. Taurodontic teeth in cone beam computed tomography: Pictorial review. Nemesis. Negat. Eff. Med. Sci. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 33, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, D.J.; Al-Nazhan, S.A.; Al-Maflehi, N.; Soman, C. Root and canal morphology of mandibular premolar teeth in a Kuwaiti subpopulation: A CBCT clinical study. Eur. Endod. J. 2020, 5, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfawaz, H.; Alqedairi, A.; Al-Dahman, Y.H.; Al-Jebaly, A.S.; Alnassar, F.A.; Alsubait, S.; Allahem, Z. Evaluation of root canal morphology of mandibular premolars in a Saudi population using cone beam computed tomography: A retrospective study. Saudi Dent. J. 2019, 31, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, Y. Mandibular second molar root canal morphology and variants in a Korean subpopulation. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, J.K.; Ghosh, S.; Mathur, V.P. Root canal morphology of primary molars–A cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2022, 33, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoncheh, Z.; Moghaddam-Zadeh, B.; Kharazi Fard, M.J. Root morphology of maxillary first and second molars in an Iranian population using cone-beam computed tomography. Front. Dent. 2020, 17, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, J.; Velozo, C.; Albuquerque, D.; Soares, C.; Oliveira, H.; Pontual, M.L.; Pontual, A. Morphological Study of Root Canals of Maxillary Molars by Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Sci. World J. 2022, 1, 4766305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, R.J.; Deroose, C.A.; Calberson, F.L. The radix entomolaris in mandibular first molars: An endodontic challenge. Int. Endod. J. 2004, 37, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramugade, M.M.; Kuanr, S.; Pawar, S. Comprehensive management of endodontic variants Radix Entomolaris and Radix Paramolaris—A case series. Acta Sci. Dent. Sci. 2017, 1, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.S.; Kim, S.O.; Choi, B.J.; Son, H.K.; Lee, J.H. Clinical management of radix entomolaris in a mandibular first molar: A case report. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifman, A.; Chanannel, I. Prevalence of taurodontism found in radiographic dental examination of 1,200 young adult Israeli patients. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1978, 6, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, B.W.; Damm, D.D.; Allen, C.M.; Chi, A.C. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Fan, B.; Fan, W.; Gutmann, J.L. Root and root canal morphology in maxillary second molar with fused root from a native Chinese population. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.A.; Versiani, M.A.; De-Deus, G.; Dummer, P.M.H. A new system for classifying root and root canal morphology. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, H.G.; Cox, F.L. C-shaped canal configurations in mandibular molars. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1979, 99, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Fan, B.; Gutmann, J.L.; Fan, M. Identification of C-shaped canal in mandibular second molars. Part I: Radiographic and clinical analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2004, 37, 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Chohayeb, A.A. Dilaceration of permanent teeth: Report of a case. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1983, 55, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, R.G.; McNamara, J.A.; McNamara, C.M. Dental dilacerations: Etiology, clinical features, and management. Dent. Update 1989, 16, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Thoma, K.H.; Goldman, H.M. The pathology of dental cementum: A critical review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1941, 28, 1989–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Consolaro, A. Hypercementosis: Concepts, clinical implications, and its possible role in dental practice. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2012, 17, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarak, H.; Tajrin, A.; Gazali, M.; Rahman, F.U.A. Impacted mandibular third molars: A comparison of orthopantomography and cone-beam computed tomography imaging in predicting surgical difficulty. Arch. Craniofacial Surg. 2024, 25, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj Husain, A.; Stadlinger, B.; Winklhofer, S.; Bosshard, F.A.; Schmidt, V.; Valdec, S. Imaging in third molar surgery: A clinical update. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinfort, K.; Chalub, M.; Gloria Mora, C.; Zaror, C.; Monardes, H.; Abarca, J. Prevalence and Morphology of Extra-Roots in Mandibular Molars: A Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Study. Int. J. Morphol. 2024, 42, 1761–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkhaneh, M.; Karkehabadi, H.; Alafchi, B.; Shokri, A. Association of root morphology of mandibular second molars on panoramic-like and axial views of cone-beam computed tomography. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- y Baena, R.R.; Beltrami, R.; Tagliabo, A.; Rizzo, S.; Lupi, S.M. Differences between panoramic and Cone Beam-CT in the surgical evaluation of lower third molars. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.Y.; Hung, K.F.; Li, D.T.S.; Yeung, A.W.K. Application of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Risk Assessment of Lower Third Molar Surgery. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzen, L.H.; Wenzel, A. Efficacy of CBCT for assessment of impacted mandibular third molars: A review–based on a hierarchical model of evidence. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2015, 44, 20140189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Author(s), Year | Population/Tooth Type | Imaging Method | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kantilieraki, E et al., 2019 [20] | Greek population, mandibular first and second molars | CBCT | Did not include third molars |

| 2 | Abarca J et al., 2020 [21] | Chilean population, mandibular molars | CBCT | Excluded because MTMs not included |

| 3 | D Li et al., 2025 [22] | Northern Chinese population, mixed molars | CBCT | Taurodontism in mixed molars, not MTM-specific |

| 4 | Fourneau D, Olszewski R., 2023 [23] | Review, various tooth types | CBCT | No quantitative MTM data |

| 5 | Alenezi MA et al., 2020 [24] | Kuwaiti population, first and second molars | CBCT | 2D imaging only |

| 6 | Alfawaz et al., 2019 [25] | Saudi population, premolars | CBCT | Different tooth group (premolars) |

| 7 | Kim S et al., 2016 [26] | Korean population, mandibular molars | Panoramic | Lacked CBCT imaging |

| 8 | Dhillon J.K. et al., 2022 [27] | Indian population, primary molars | CBCT | Not permanent third molars |

| 9 | Ghoncheh Z et al., 2020 [28] | Iranian population, maxillary first and second molars | CBCT | Did not include mandibular third molars |

| 10 | Magalhães KM et al., 2022 [29] | Brazilian population, maxillary molars | CBCT | Non-mandibular third molars |

| Aberration | Author(s), Year | Population | Sample/Method | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root number variation | Priyank H. et al., 2023 [6] | Indian | CBCT n = 277 MTMs | Two roots ~95%; three roots ~1.5%; single root ~2.8%; four roots ~0.4% |

| C-shaped roots | Hiran-us et al., 2021 [7] | Thai | CBCT n = 542 MTMs | C-shaped ~16.6%; fused roots ~20%; two separate roots ~68% |

| Dilaceration | Miloglu et al., 2010 [8]; Malčić et al., 2006 [9] | Turkish and Croatian | Panoramic | Prevalence 10–22%; curvature mesio-distal or bucco-lingual |

| Taurodontism | Li et al., 2023 [10]; Kırmızı et al., 2025 [11] | Chinese and Turkish-Cypriot | CBCT | Tooth-level prevalence 7–8%; MTM-specific rare |

| Hypercementosis | Ohbayashi et al., 2021 [12] | Japanese | CBCT n = 1160 | Prevalence rises with age; >90% ≥40 years |

| Radix entomolaris | Carlsen and Alexandersen, 1990 [13]; Tu et al., 2007 [14] | Morphological | Case reports; rare in MTMs | Distolingual extra root; mostly anecdotal in MTMs |

| Radix paramolaris | Calberson et al., 2007 [15]; Bhopatkar et al., 2023 [16] | Morphological | Case reports | Buccal accessory root; exceptionally rare in MTMs |

| Root fusion | Hiran-us et al., 2021 [7]; Fernandes et al., 2014 [17] | Thai and other | CBCT | Fused roots ~20%; conical morphology; surgical difficulty increased |

| Aberration | Population/Country | Region | Prevalence Range | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three-rooted (RE/RP) | Thai, Jordanian, Chinese | Asia | ~1–10% | [6,7,14,16] |

| C-shaped canal | Thai, Chinese, Korean | Asia | 10–17% | [7,9] |

| Root fusion | Thai, Brazilian | Asia/South America | ~20% | [7,17] |

| Dilaceration | Turkish, Croatian | Europe | 10–22% | [8,9] |

| Taurodontism | Chinese, Turkish-Cypriot | Asia/Europe | 7–8% (rare in MTM) | [10,11] |

| Hypercementosis | Japanese | Asia | Age-dependent; >90% ≥40 y | [12] |

| Radix entomolaris | Chinese, Indian | Asia | <2% (rare in MTMs) | [13,14] |

| Radix paramolaris | Indian, Brazilian | Asia/South America | Rare; case reports | [15,16] |

| Category | Subgroup | Definition/Description | Surgical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 1 root | Single-rooted MTM | Often easier extraction; may be fused or conical |

| 2 roots | Standard mesial and distal roots | Most common; separate roots allow predictable luxation | |

| 3 roots | Typically includes distolingual RE | Rare; requires tri-section and careful apical leverage | |

| 4 roots | Rare; combinations of RE/RP | Highly complex; pre-op CBCT mandatory | |

| Shape/Morphology | Fusion | Partial or complete coalescence of roots | Reduced interradicular septum; risk of root fracture; requires buccal troughing and crown-to-root separation |

| C-shaped | Continuous or semicolon canal; lingual/buccal groove | Thin dentin; high risk of fracture; controlled sectioning advised | |

| Taurodontism | Elongated pulp chamber, apically displaced furcation | Short roots; limited elevator purchase; careful apical handling | |

| Hypercementosis | Excess cementum deposition | Enlarged root cross-section; may impede extraction; wider osteotomy may be needed | |

| Position/Orientation | Dilaceration | Curved or hooked apices | Impedes straight-line removal; risk of apical fracture; consider apex-first retrieval |

| Divergence/Angulation | Mesio-distal or bucco-lingual root orientation | Alters elevation path; increases risk of fracture or canal proximity injury |

| Aberration | Definition | Prevalence in MTMs | Surgical Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-rooted | MTM with one conical root | 2–3% | Limited purchase for elevators; increased fracture risk | [6,7] |

| Two-rooted | MTM with mesial and distal roots | 68–90% | Standard extraction technique | [6,7] |

| Three-rooted | MTM with accessory RE or RP | 7–10% | Requires tri-section; careful apical leverage | [6,7,16] |

| Four-rooted | Rare; usually case reports | <1% | Complex extraction; CBCT strongly recommended | [6] |

| Radix Entomolaris | Distolingual accessory root | <2% | Tri-section, apical release; avoid lingual/IAC injury | [15] |

| Radix Paramolaris | Buccal accessory root | Rare; case reports | CBCT mapping, controlled extraction | [16] |

| Hypo-/Meso-/Hypertaurodont | Apical displacement of pulp floor; root shortening | Tooth-level 7–8%; individual 20–29% (mostly non-MTMs) | Reduced elevator purchase; require wider coronal troughing; control sectioning | [10,11] |

| Root fusion | Coalescence of two or more roots | ~20% | Reduced interradicular septum; increased risk of root fracture; buccal troughing and crown-to-root separation recommended | [6,7,17] |

| C-shaped canal | Fused root forming crescent or semicolon canal | 10–17% | Thin dentin walls; controlled sectioning; avoid excessive force; apex release | [7] |

| Dilaceration | Curved or hooked root apex (>20–40°) | 10–22% | Impedes straight-line removal; risk of apical fracture; may require coronectomy or apex-first approach | [8,9] |

| Hypercementosis | Cemental thickening along root | Age-dependent: 0% ≤19 y, ~14% (20–24 y), ~58% (25–29 y), >90% ≥40 y | Enlarged root cross-section; requires wider apical osteotomy and careful apical release; CBCT recommended | [12] |

| Aberration | Prevalence (MTMs) | Key Surgical Implications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two roots | 68–90% | Standard extraction; predictable luxation | [6] |

| Three roots (RE/RP) | 7–10% | Tri-section; careful apical release | [6,14,16] |

| Single root | 2–3% | May be conical; requires careful luxation | [6,7] |

| Fused roots | ~20% | Buccal troughing; risk of fracture | [7,17] |

| C-shaped | 10–17% | Controlled sectioning; thin dentin risk | [7,17] |

| Dilaceration | 10–22% | Apex-first retrieval; coronectomy if near IAN | [8,9] |

| Taurodontism | 1–5% (MTM-specific) | Wider coronal troughing; careful elevators | [10,11] |

| Hypercementosis | Age-dependent; up to 90% ≥40 y | Wider osteotomy; apical release | [12] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaccheo, F.; Petroni, G.; Cicconetti, A. Radicular Aberrations of Mandibular Third Molars: Relevance for Oral Surgery—A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12756. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312756

Zaccheo F, Petroni G, Cicconetti A. Radicular Aberrations of Mandibular Third Molars: Relevance for Oral Surgery—A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12756. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312756

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaccheo, Fabrizio, Giulia Petroni, and Andrea Cicconetti. 2025. "Radicular Aberrations of Mandibular Third Molars: Relevance for Oral Surgery—A Comprehensive Narrative Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12756. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312756

APA StyleZaccheo, F., Petroni, G., & Cicconetti, A. (2025). Radicular Aberrations of Mandibular Third Molars: Relevance for Oral Surgery—A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12756. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312756