Characteristics of Molecular Properties of Carbohydrates and Melanoidins in Instant Coffee and Coffee Substitutes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

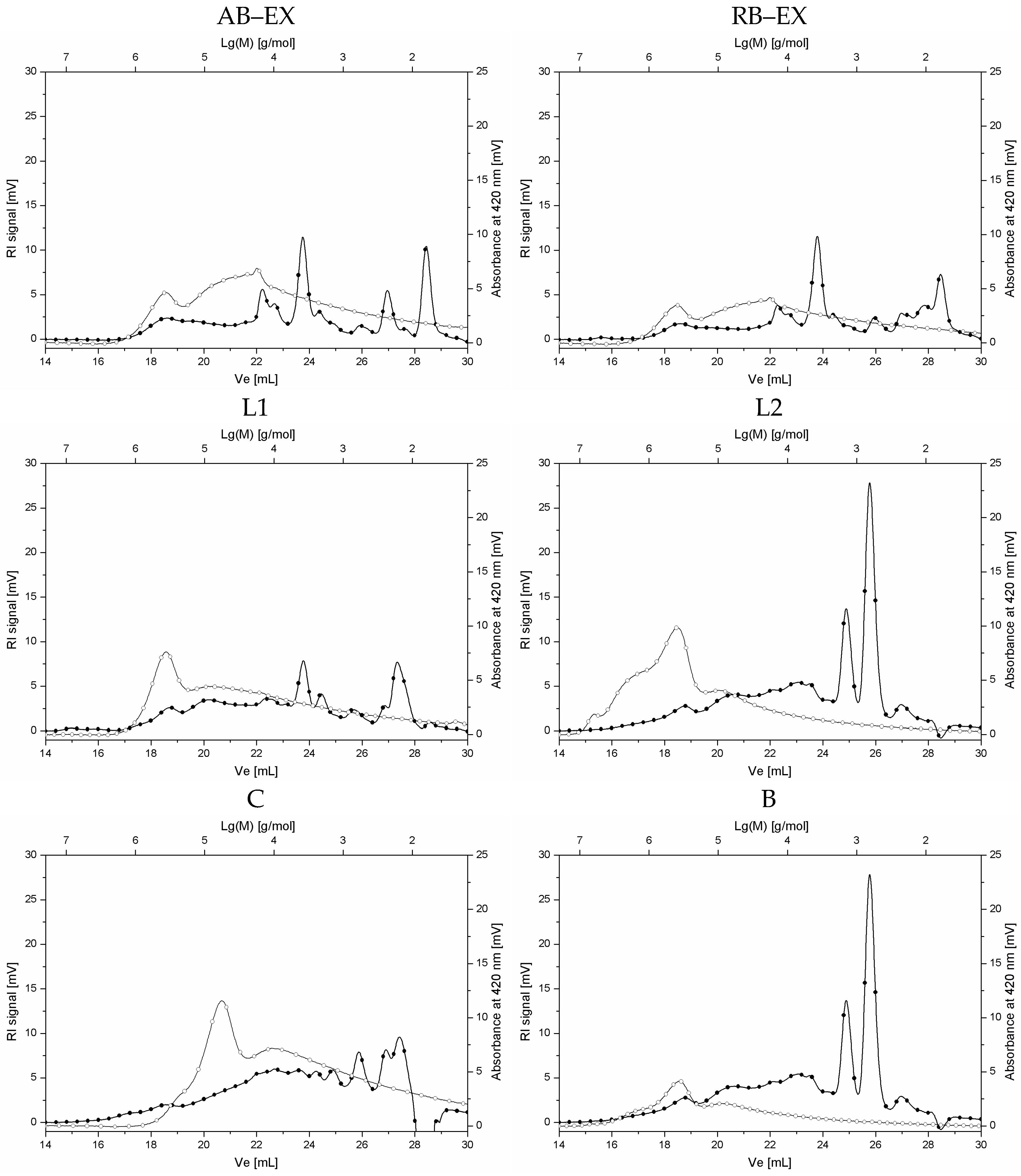

- Roasted coffee beans 100% C. Arabica (AB) and 100% C. canephora (Robusta, RB);

- -

- Lyophilized instant coffee powders of two commercially available brands (L1 and L2);

- -

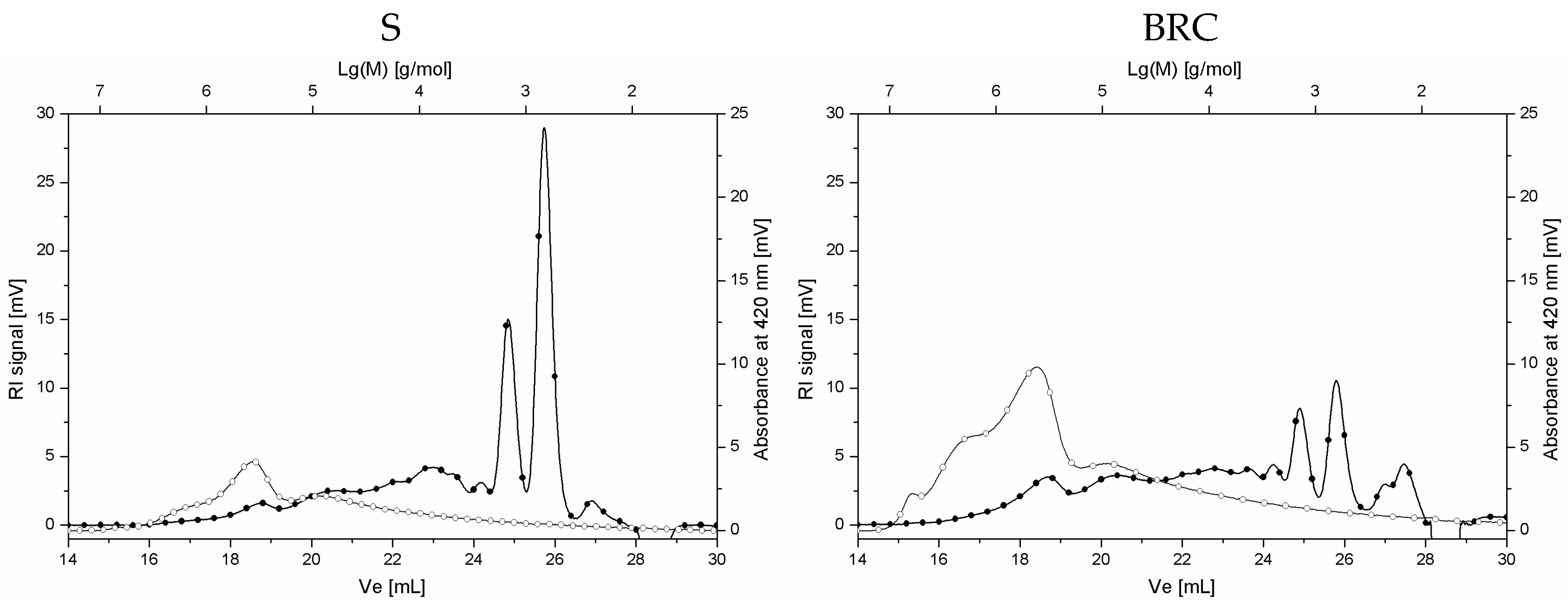

- Coffee substitutes (instant) produced from roasted chicory root (C), roasted barley grains (B), roasted spelt wheat grains (S), and a blend of roasted grains of barley and rye, and chicory root (BRC).

2.1. Preparation of Lyophilized Samples of Arabica and Robusta Coffee Beans

2.2. Determination of Dry Basis Content in Instant Coffee and Coffee Substitutes

2.3. Determination of the Caffeine Content in the Samples

2.4. Analysis of Molecular Weight Distribution of Carbohydrates and Melanoidins in Instant Coffee Samples and Coffee Substitutes

2.5. Analysis of Monosaccharide Profiles After Acid Hydrolysis of Instant Coffee and Coffee Substitutes Using HPLC/RI Method

2.6. Statistical Analysis of the Results

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frankowski, M.; Kowalski, A.; Ociepa, A.; Siepak, J.; Niedzielski, P. Kofeina w kawach I ekstraktach kofeinowych I odkofeinowanych dostępnych na polskim rynku. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol. 2008, XLI, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller, M.A. The Chemical Components of Coffee. In Caffeine; Spiller, G.A., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; pp. 97–161. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, T.J. The origins of Tea, Coffee and Cocoa as Beverages. In Teas, Cocoa and Coffee: Plant Secondary Metabolites and Health; Crozier, A., Ashihara, H., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pazola, Z.; Cieślak, J. Changes in carbohydrates during the production of coffee substitute extracts especially in the roasting processes. Food Chem. 1979, 4, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilawati, I.D.A.; Muzeka, F. Antioxidant Activity and Phytochemicals of Freeze-dried and Spray-dried Soluble Coffee Brews. Coffee Sci. 2025, 20, e202347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Gaida, M.; Franchina, F.A.; Stefanuto, P.H.; Focant, J.F. Distinguishing between Decaffeinated and Regular Coffee by HS-SPME-GC×GC-TOFMS, Chemometrics, and Machine Learning. Molecules 2025, 27, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worobiej, E.; Relidzyńska, K. Kawy zbożowe–charakterystyka I właściwości przeciwutleniające. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol. 2011, XLIV, 625–629. [Google Scholar]

- Guertin, K.; Lotfield, E.; Boca, S.; Sampson, J.; Moore, S.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, W.; Xiong, X.; Freedman, N.; Cross, A.; et al. Serum biomarkers of habitual coffee consumption may provide insight into the mechanism underlying the association between coffee consumption and colorectal cancer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak–Majewska, M. Analiza Zawartości Szczawianów w Popularnych Naparach herbat I Kaw. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol. 2013, XLVI, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz, E.; Zawirska-Wojtasiak, R.; Przygoński, K. Bioactive β-carbolines norharman and harman in traditional and novel raw materials for chicory coffee. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robefroid, B.R.; Van Loo, J.A.E.; Gibson, G.R. The Bifidogenic Nature of Chicory Inulin and Its Hydrolysis Products. J. Nutr. 1998, 128, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, V.A. The prebiotic properties of oligofructose at low intake levels. Nutr. Res. 2001, 21, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolida, S.; Meyer, D.; Gibson, G.R. A double-blind placego-controlled study to establish the bifidogenic dose of inulin in healthy humans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhnik, Y.; Raskine, L.; Champion, K.; Andrieux, C.; Penven, S.; Jacobs, H.; Simoneau, G. Prolonged administration of low-dose inulin stimulates the growth of bifidobacteria in humans. Nutr. Res. 2007, 27, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, R.M.; Chu, C.M. Material balance on free sugars in the production of instant coffee. In Proceedings of the 15th ASIC Colloquium, Montpellier, France, 6–11 June 1993; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Poisson, L.; Blank, I.; Dunkel, A.; Hofmann, T. The Chemistry of Roasting–Decoding Flavor Formation. In The Craft and Science of Coffe, 1st ed.; Folmer, B., Ed.; Accademic Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 273–309. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, A.G.W. Chemistry I: Non-volatile Compounds. In Coffee: Recent Development; Clarke, R., Vitzthum, O., Eds.; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oestreich-Janzen, S. Chemistry of Coffe. In Comprehensive Natural Products II: Chemistry and Biology; Hung-Wen, L., Mander, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 1085–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jung, S.; Kim, E.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, C.Y.; Ha, J.H.; Jeaong, Y. Physciochemical characteristics of Ethiopian Coffea arabica cv. Heirloom coffe extracts with various roasting conditions. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarini, L.; Gilli, R.; Gombac, V.; Abatangelo, A.; Bosco, M.; Toffanin, R. Polysaccharides from hot water extracts of roasted Coffea arabica beans isolation and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 1999, 40, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F.M.; Coimbra, M.A. Roasted Coffee High Molecular Weight Material–Polysaccharide Melanoidin Mixtures or Polysaccharide–Melanoidin Complexes? In Proceedings of the COST Action 919 Workshops, Oslo, Norway, 31 May–1 June 2002. Madrid, Spain, 18–19 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterveld, A.; Harmsen, J.S.; Voragen, A.G.J.; Schols, H.A. Extraction and characterization of polysaccharides from green and roasted Coffea arabica beans. Carbohydr. Pol. 2003, 52, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F.M.; Domingues, M.R.; Coimbra, M.A. Arabinosyl and glucosyl residues as structural features of acetylated galactomannans from green and roasted coffee infusions. Carbohydr. Res. 2005, 340, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redgwell, R.J.; Trovato, V.; Curti, D.; Fischer, M. Effect of roasting on degradation and structural features of polysaccharides in Arabica coffee beans. Carbohydr. Res. 2002, 337, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illy, A. Espresso Coffee the Science of Quality; Illy, A., Viani, R., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, G.M. Possible applications of enzymes in coffe processing. In Proceedings of the 9th ASIC Colloqium, London, UK, 16–20 June 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, F.M.; Coimbra, M.A. Influence of polysaccharide composition in foam stability of espresso coffee. Carbohyd. Polym. 1998, 37, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henle, T.; Deppisch, R.; Ritz, E. The Maillard reaction–from food chemistry to uraemia research. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1996, 11, 1718–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.T.; Hwang, H.I.; Yu, T.H.; Zhang, J. An overview of the Maillard reactions related to aroma generation in coffee. In Proceedings of the 15th ASIC Colloquium, Montpellier, France, 6–11 June 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ledl, F.; Schleicher, E. Die Maillard-Reaktion in Lebensmitteln und im menschilchen Körper–neue Ergebnisse zu Chemie, Biochemi und Medizin. Angew. Chem. 1990, 102, 597–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gniechwitz, D.; Reichardt, N.; Meiss, E.; Ralph, J.; Steinhart, H.; Blaut, M.; Bunzel, M. Characterization and Fermentability of an Ethanol Soluble High Molecular Weight Coffee Fraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5960–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Cadwallader, K.R. Identification of characterizing aroma components of roasted chicory “coffee” brews. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13848–13859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh, M.; A-Jaafreh, A.M.; Al-Dal’in, H.; Qaralleh, H.; Alqaraleh, M.; Khataibeh, M. Roasted date and barley beans as an alternative’s coffee drink: Micronutrient and caffeine composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2021, 12, 1079–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Adebisi, A.; Malebogo, L.; Aderbigibe, O. Proximate, antioxidant and sensory properties of coffe substitute developed from seeds of Adansonia digitata L. and Phoenix dactylifera L. Afr. J. Sci. Nat. 2020, 9, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, B.B.; Huang, R.; Liu, D.; Ye, X.; Guo, M. Potential valorisation of baobab (Adansonia digitata) seeds as a coffee substitute: Insights and comparisons on the effect of roasting on quality, sensory profiles, and characterization of volatile aroma compounds by HS-SPME/GC-MS. Food Chem. 2022, 394, 133475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsonowicz, M.; Regulska, E.; Karpowicz, D.; Leśniawska, B. Antioxidant properties of coffe substitutes rich in polyphenols and minerals. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petronilho, S.; Navega, J.; Pereira, C.; Almeida, A.; Siopa, J.; Nunes, F.M.; Coimbra, M.A.; Passos, C.P. Bioactive Properties of Instant Chicory Melanoidins and Their Relevance as Health Promoting Food Ingredients. Foods 2023, 12, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perović, J.; Tumbas, Š.; Kojić, J.; Krulj, J.; Moreno, D.A.; Garcia-Viguera, C.; Bodroža-Solarov, M.; Ilić, N. Chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) as a food ingredient–Nutritional composition, bioactivity, safety and health claims: A review. Food Chem. 2021, 336, 127676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonietti, S.; Silva, A.M.; Simoes, C.; Almeida, D.; Felix, L.M.; Papetti, A.; Nunes, F.M. Chemical Composition and Potential Biological Activity of Melanoidins From Instant Soluble Coffee and Instant Soluble Barley: A Comparative Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 825584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 11294; Roasted Ground Coffee—Determination of Moisture Content—Method by Determination of Loss in Mass at 103 Degrees C (Routine Method). International Standard Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994.

- Srdjenovic, B.; Djordjevic-Milic, V.; Grujic, N.; Injac, R.; Lepojevic, Z. Simultaneous HPLC Determination of Caffeine, Theobromine, and Theophylline in Food, Drinks, and Herbal Products. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2008, 46, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buksa, K.; Nowotna, A.; Ziobro, R. Application of cross-linked and hydrolyzed arabinoxylans in baking of model rye bread. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stój, A.; Węgiel, P.; Sosnowska, B.; Czernecki, T.; Wlazły, A. Ocena jakości kaw rozpuszczalnych. Towraoznawcze Probl. Jakości 2014, 3, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wołosiak, R.; Krawczyk, W.; Derewiaka, D.; Majewska, E.; Kowalska, J.; Drużyńska, B. Ocena jakości I właściwości przeciwutleniających wybranych kaw rozpuszczalnych. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol. 2015, XLVII, 568–572. [Google Scholar]

- Chrostowska-Siwek, I.; Galusik, D. Próba rozróżnienia kaw o rożnym pochodzeniu geograficznym na podstawie analizy standardowych wyróżników fizykochemicznych i związków lotnych. Zeszyty Naukowe/Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Poznaniu 2011, 196, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Matysek-Nawrocka, M.; Cyrankiewicz, P. Substancje biologicznie aktywne pozyskiwane z herbaty, kawy i kakao oraz ich zastosowanie w kosmetykach. Post. Fitoter. 2016, 17, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Capek, P.; Paulovicova, E.; Matulova, M.; Mislovicova, D.; Navarini, L.; Suggi-Liverani, F. Coffea arabica instant coffee–Chemical view and immunomodulating properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 103, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, M.D.; Ames, J.M.; Gordon, M.H. Effect of Roasting on the Antioxidant Activity of Coffee Brews. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3698–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Duran, S.A.; Lean, M.E.J.; Combet, E. Roasted instant coffees: Analysis of (poly)phenols and melanoidins antioxidant capacity, potassium and sodium contents. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, E63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Hernandez, L.M.; Chavez-Quiroz, K.; Medina-Juarez, L.A.; Meza, N.G. Phenolic Characterization, Melanoidins, and Antioxidant Activity of Some Commercial Coffees from Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2012, 56, 430–435. [Google Scholar]

- Linne, B.M.; Tello, E.; Simons, C.T.; Peterson, D.G. Chemical characterization and sensory evaluation of a phenolic-rich melanoidin isolate contributing to coffee astringency. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 2870–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.S.P.; Nunes, F.M.; Simoes, C.; Maciel, E.; Domingues, P.; Domingues, M.R.M.; Coimbra, M.A. Data on coffee composition and mass spectrometry analysis of mixtures of coffee related carbohydrates, phenolic compounds and peptides. Data Brief. 2017, 13, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, M.; Gerald, E.D.; Parchet, J.M.; Viani, R. Chromatographic Profile of Carbohydrate in Commercial Soluable Coffees. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1989, 37, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkijowska, A.; Rzedzicki, Z.; Sobota, A.; Sykut-Domańska, E. Jęczmień w żywieniu człowieka. Polish J. Agron. 2016, 25, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałązka, I. Skład mączki cykoriowej wybranych odmian cykorii, zróżnicowanych wielkością i terminem zbioru korzeni. Żywność. Nauka Technol. Jak. 2002, 3, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Trugo, L.C. Carbohydrates. In Coffe, 1st ed.; Clarke, R.J., Macrea, R., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publlshers Ltd.: Barking, UK, 1985; Volume 1, pp. 83–114. [Google Scholar]

- Redgwell, R.; Fischer, M. Coffee carbohydrates. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, A.G.W. Carbohydrates in coffee. In Proceedings of the 19em Colloque Scientifique International sur le Café, Triest, Italy, 14–18 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, B.; Blank, I.; Hofmann, T. Crema Formation, Stabilization, and Sensation. In The Craft and Science of Coffee; Folmer, B., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; Chapter 17; pp. 399–417. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, F.M.; Coimbra, M.A. Chemical Characterization of the High-Molecular-Weight Material Extracted with Hot Water from Green and Roasted Robusta Coffees As Affected by the Degree of Roast. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7046–7052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo, O.R.; Alevaro, A.C. Coffee’s Phenolic Compounds. A general overview of the coffee fruit’s phenolic composition. Revis. Bionatura. 2022, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, W.J.; Michaux, S.; Bastin, M.; Bucheli, P. Changes to the content of sugars, sugar alcohols, myo-inositol, carboxylic acids and inorganic anions in developing grains from different varieties of Robusta (Coffea canephora) and Arabica (C. arabica) coffees. Plant Sci. 1999, 149, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Shastri, Y. Economic optimization of acid pretreatment: Structural changes and impact on enzymatic hydrolysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 147, 112336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinant, J.P.; Billot, A.; Bouguennec, A.; Charmet, G.; Saulnier, L.; Branlard, G. Genetic and Environmental Variations in Water-Extractable Arabinoxylans Content and Flour Extract Viscosity. J. Cereal Sci. 1999, 30, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, M.S.; Biliaderis, C.G. Structural and Functional Aspects of Cereal Arabinoxylans and 13-Glucans. Dev. Food Sci. 2000, 41, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebruers, K.; Dornez, E.; Boros, D.; Fraś, A.; Dynkowska, W.; Bedo, Z.; Rakszegi, M. Variation in the Content of Dietary Fiber and Components Thereof in Wheats in the HEALTHGRAIN Diversity Screen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9740–9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R.; Fransson, G.; Tietjen, M.; Aman, P. Content and Molecular-Weight Distribution of Dietary Fiber Components in Whole-Grain Rye Flour and Bread. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2004–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyran, M.R.; Snochowska, K.K.; Potrzebowski, M.J.; Kaźmierski, S.; Azadi, P.; Heiss, C.; Tan, L.; Ndukwe, I.; Bonikowski, R. Xylan-cellulose core structure of oat water-extractable β-glucan macromolecule: Insight into interactions and organization of the cell wall complex. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 324, 121522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zartl, B.; Silberbauer, K.; Loeppert, R.; Viernstein, H.; Praznik, W.; Mueller, M. Fermentation of non-digestible raffinose family oligosaccharides and galactomannans by probiotics. Food Funct. 2018, 3, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.Y.; Ki-Bae, H.; Chang, Y.B.; Shin, J.; Jung, E.Y.; Jo, K.; Suh, H.J. In vitro Prebiotics Effects of Malto-Oligosaccharides Containing Water-Soluble Dietary Fiber. Molecules 2020, 25, 5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.R.; Shepherd, S.J. Personal view: Food for thought–western lifestyle and susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. The FODMAP hypothesis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 21, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwafor, I.C.; Shale, K.; Achilonu, M.C. Chemical Composition and Nutritive Benefits of Chicory (Cichorium intybus) as an Ideal Complementary and/or Alternative Livestock Feed Supplement. Sci. World J. 2017, 2017, 7343928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekedam, E.K.; Schols, H.A.; van Boekel, M.A.J.S.; Smit, G. High Molecular Weight Melanodins from Coffee Brew. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7658–7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekedam, E.K.; Schols, H.A.; van Boekel, M.A.J.S.; Smit, G. Incorporation of Chlorogenic Acids in Coffee Brew Melanoidins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2055–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.S.P.; Nunes, F.M.; Domingues, M.R.; Coimbra, M.A. Coffee melanoidins: Structures, mechanisms of formation and potential health impacts. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, M.S.; Fischer, S.; Henle, T. High Molecular Weight Coffee Melanoidins Are Inhibitors for Matrix Metalloproteases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 11417–11423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, F.M.; Coimbra, M.A. Melanoidins from Coffee Infusions. Fractionation, Chemical Characteization, and Effect of the Degree of Roast. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3967–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogliano, V.; Moralej, F.J. Estimation of dietary intake of melanoidins from coffee and bread. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dills, W.L. Protein fructosylation: Fructose and the Maillard reaction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993, 58, 779S–787S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Type | Sample Code | Dry Mass Content [%] | Caffeine Content [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | AB-EX | 95.3 ± 1.1 b | 3.9 ± 0.5 d |

| RB-EX | 94.7 ± 0.7 b | 6.6 ± 0.3 e | |

| L1 | 95.8 ± 1.6 b | 3.1 ± 0.4 c | |

| L2 | 93.0 ± 0.5 a | 2.1 ± 0.3 b | |

| Coffee substitutes | C | 96.8 ± 0.7 b | 0.0 ± 0.1 a |

| B | 98.3 ± 0.0 c | 0.1 ± 0.1 a | |

| S | 95.3 ± 0.6 b | 0.0 ± 0.1 a | |

| BRC | 96.4 ± 0.9 b | 0.1 ± 0.1 a |

| Content of Polysaccharides of Mw > 2000 g/mol [%] | Content of Oligosaccharides of Mw 500–2000 g/mol [%] | Content of Mono- and Disaccharides Mw < 500 g/mol [%] | Content of Total Carbohydrates [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | ||||

| AB-EX | 39.7 ± 0.8 b | 2.0 ± 0.9 a | 5.6 ± 0.4 ab | 47.3 a |

| RB-EX | 31.3 ± 0.7 a | 3.2 ± 0.2 ab | 7.8 ± 0.3 b | 42.3 a |

| L1 | 42.9 ± 1.5 bc | 3.9 ± 0.3 ab | 9.6 ± 2.9 b | 56.3 b |

| L2 | 47.3 ± 1.0 cd | 4.7 ± 0.1 b | 6.7 ± 0.7 ab | 58.6 b |

| Coffee substitutes | ||||

| C | 58.0 ± 1.1 e | 11.4 ± 0.3 c | 17.6 ± 1.9 c | 87.0 d |

| B | 59.2 ± 2.3 e | 25.3 ± 0.5 d | 6.0 ± 0.3 ab | 90.6 d |

| S | 47.4 ± 1.1 cd | 25.5 ± 0.2 d | 2.3 ± 0.2 a | 75.2 c |

| BRC | 52.1 ± 0.3 d | 10.8 ± 0.9 c | 6.2 ± 0.5 ab | 69.0 c |

| Glc [%] | Xyl [%] | Gal [%] | Ara [%] | Man [%] | Fru [%] | Total Sugar [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | |||||||

| AB-EX | 2.8 ± 0.1 a | 0.4 ± 0.3 a | 14.3 ± 0.2 b | 1.6 ± 0.3 c | 17.9 ± 1.1 cd | 4.8 ± 0.1 d | 41.8 ± 1.0 b |

| RB-EX | 0.8 ± 0.1 a | 0.3 ± 0.1 a | 14.3 ± 0.5 b | 0.9 ± 0.4 ab | 14.4 ± 0.4 b | 3.6 ± 0.1 cd | 34.3 ± 0.6 a |

| L1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 a | 0.1 ± 0.1 a | 20.7 ± 0.5 c | 0.6 ± 0.1 ab | 18.5 ± 0.5 d | 1.8 ± 0.1 b | 44.5 ± 0.7 c |

| L2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 a | 0.3 ± 0.3 a | 24.2 ± 0.4 d | 2.7 ± 0.2 c | 16.1 ± 0.2 bc | 2.3 ± 0.2 bc | 47.2 ± 0.0 d |

| Coffee substitutes | |||||||

| C | 7.2 ± 0.1 b | 0.4 ± 0.3 a | 0.3 ± 0.2 a | 0.8 ± 0.4 ab | 0.0 ± 0.1 a | 48.5 ± 0.5 f | 57.3 ± 0.2 e |

| B | 61.9 ± 1.3 d | 0.9 ± 0.1 ab | 0.5 ± 0.1 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 ab | 0.4 ± 0.2 a | 0.5 ± 0.1 a | 65.0 ± 0.7 f |

| S | 63.5 ± 1.3 d | 1.4 ± 0.3 b | 1.0 ± 0.1 a | 0.3 ± 0.1 a | 0.3 ± 0.2 a | 0.4 ± 0.2 a | 67.1 ± 0.9 f |

| BRC | 47.1 ± 1.0 c | 1.4 ± 0.1 b | 0.5 ± 0.2 a | 0.6 ± 0.3 ab | 0.2 ± 0.1 a | 8.4 ± 0.6 e | 58.2 ± 0.7 e |

| Sample Code | Peak Area of Melanoidins Detected at UV420nm [mV × min] |

|---|---|

| Coffee | |

| AB-EX | 83.3 ± 0.5 e |

| RB-EX | 53.3 ± 0.8 b |

| L1 | 64.3 ± 1.1 c |

| L2 | 52.7 ± 0.9 b |

| Coffee substitutes | |

| C | 98.1 ± 1.2 f |

| B | 63.8 ± 1.1 c |

| S | 24.7 ± 1.4 a |

| BRC | 71.7 ± 0.8 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buksa, K.; Szczypek, M. Characteristics of Molecular Properties of Carbohydrates and Melanoidins in Instant Coffee and Coffee Substitutes. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12627. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312627

Buksa K, Szczypek M. Characteristics of Molecular Properties of Carbohydrates and Melanoidins in Instant Coffee and Coffee Substitutes. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12627. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312627

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuksa, Krzysztof, and Michał Szczypek. 2025. "Characteristics of Molecular Properties of Carbohydrates and Melanoidins in Instant Coffee and Coffee Substitutes" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12627. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312627

APA StyleBuksa, K., & Szczypek, M. (2025). Characteristics of Molecular Properties of Carbohydrates and Melanoidins in Instant Coffee and Coffee Substitutes. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12627. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312627